Summary of Georges Rouault

Though he joins the ranks of the major artists linked to the heroic avant-garde years in Paris, Rouault cut something of a solitary figure amongst his peers. He nevertheless formed early career associations and friendships with Henri Matisse, Albert Marquet, Henri Manquin and Charles Camoin and this brought him into the fold of the Fauvists with whom he exhibited at their famous 1905 exhibition at the Salon d'Automne. However, his work carried strong elements of Expressionism, which had never found much favor outside of Scandinavia and Germany. By the beginning of the First World War Rouault was turning more and more away from watercolor and oil on paper towards oil and canvas and he applied his paint through thick, rich, layers which helped amplify his raw and bold forms. His colors, awash with deep blues, contained within heavy black lines, produced art that was reminiscent of stained glass windows and supported subject matter that became more overtly religious with a strong recurring theme of the power of redemption. The majority of his career was devoted to the human figure - specifically clowns, prostitutes and Christ - but during the last decade of his life his palette allowed for pastel shades of green and yellow to impinge on canvases that placed his figures in charming mystical landscapes.

Accomplishments

- Unique amongst modernists, Rouault's artistic evolution was informed by a devout Catholic faith. Drawing on the ideas of religiously-inspired intellectuals of his time, Rouault looked towards symbolism and primary colors to express the core values of Catholicism; a highly unfashionable (and single-minded) worldview when one considers the progressive milieu in which he was working.

- As was the norm amongst modernists who wanted to represent the lives of "ordinary" workers, Rouault's prostitute paintings treated his sitters with a genuine, non-judgemental, empathy. Rouault represented his workers with an honest, unadorned, realism that allowed for (or, in his view, insisted upon) an emphasis on naked sensuality. He was thus able to eclipse the aims of his peers by the way he drew attention to the contradictions at play between his models' Rubenesque seductiveness and their societal exploitation.

- In an age of science and reason; and age in which faith was considered the philosophical property of only innocent minds, Rouault treated the figure of Jesus, not with irony, nor even distain, but rather as the true saviour of all mankind. His masterpiece is considered to be a book of 58 collated illustrations. Revealing the strong influence of German Expressionist woodcuts, Miserere (1922-1927) lays bare the stark spectacle of everyday human suffering with the figure of Christ presented in these pages as the redeemer of all the wretched souls.

- Towards the end of his career, Rouault produced a series of "biblical landscapes" (landscapes populated with religious figures). Unlike the earlier works of artists like Henri Matisse who explored the expressionist landscape via the "joie de vivre" of reveling freely in the physical sensation and direct experiences of nature, Rouault combined his flattened symbolic landscapes with classical influences thereby imbuing them with a spiritual aura that was wanting in the work of his contemporaries.

Important Art by Georges Rouault

Jeu de massacre (Slaughter)

The scene represents a fairground booth of the French version of the Aunt Sally game. The life-sized figures in the background are puppets to be knocked down by wooden balls that the lady in red in the foreground appears to be selling. The sign on the top of the figures that reads "La Noce A nini Patte en l'Air" indicates that the scene is supposed to be the wedding of Nini patte en l'air, a famous Moulin Rouge dancer. The watercolor is dark in tone. Lines are frenetic and sketchy which accentuates the angry atmosphere of the composition as a whole.

It is traditional that the puppets in the Aunt Sally game are based on local or national public figures. Here, Rouault chooses to comment on the anonymous bourgeois class by depicting a dazed and unanimated row of characters. The stylization of the puppets aggravates the caricature as we cannot differentiate the puppets from the human beings. The fun dimension of the game gives way to a grotesque and pathetic portrayal of the bourgeois classes. Moreover, the party here is supposed to be attending the wedding of a minor celebrity, which adds to the satirical depiction of the class who would look down on such festivities.

Rouault seems to have most empathy for the entertainer. Dressed in an ostentatious red dress, she is at the center of the scene and has a stern and deep glaze (unlike her bland counterparts). However, instead of attracting players, she seems melancholic and as bored as her puppets. The artist removes the shiny and lively side of the entertainment life and reveals a sadder and more somber angle. The work (made on paper) was first exhibited at the 1905 Salon d'Automne that premiered the Fauves group. It features the several themes that Rouault would depict during his future career: social criticism, entertainers, prostitution and leisure.

Watercolor, gouache, India ink and pastel on paper - Centre Georges Pompidou, Paris

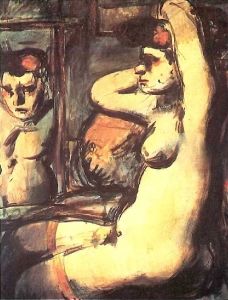

Two Nudes (The Sirens)

Prostitutes are a recurrent theme in the career of Rouault. Here, we have two seated women ("the sirens") waiting for customers. They are naked except for their fine jewelry and their coiffured hairstyles. The bright colors of their flesh contrast with the blueish background of the night and emphasize the coarseness of their large and saggy bodies. The women look bored and tired. However, one of the women could be smiling (probably at a potential client).

Rouault does not seek to condemn his models, but wishes to expose (and denounce) the harsh realities of their profession. Their exposed and raw flesh personifies the women's sad vulnerability as Rouault seeks to convey a sense of empathy towards these women. With gestural heavy black lines - that will soon become his signature style - he outlines the femininity of their curves. With warm color palette for the flesh, he emphasizes too the sensuality of their nudity. By naming them "sirens", moreover, Rouault recalls the witty caricatures of Daumier whom he admired, and accentuates the bitter contrast between the touching voluptuousness of these women and their social and moral exploitation.

Gouache on paper - Norton Simon Museum

Miserere

This monumental work is considered by many to be Rouault's masterpiece. The artist started to work on it as early as 1912, preparing a book of drawings in Indian ink. In 1916, the "difficult" art dealer Ambroise Vollard commissioned a book of prints and Rouault decided to transfer these original drawings into copperplates that would later become the prints for Miserere. Originally conceived as a two-volume book, this publication contains 58 illustrations that fall into two sections: Miserere and Guerre (War). It was finished in 1927 but would not be published until 1948.

Many critics have praised Rouault for his mastery of the art of printing. The artist reworked these plates repeatedly over two decades using aquatint, etching, and engraving to achieve rich, blacks and grays to produce his heavily outlined figures. As Rouault stated in his Introduction to the book: "I have tried, taking infinite pains, to preserve the rhythm and quality of the original drawing. I worked unceasingly on each plate, with varying success, using many different tools. There is no secret about my methods. Dissatisfied, I reworked the plates again and again, sometimes making as many as fifteen successive states; for I wished them as far as possible to be equal in quality".

The prints are all black and white, which may have been influenced by German Expressionist woodcuts and illustrated books, roughly twenty-five by nineteen inches in size, and composed as a vignette with a legend written by Rouault himself. The imagery itself combines religious iconography and representations of both human misery and fraternity. Plate 3 focuses on the life and passion of Christ and the Catholic concept of human suffering. Rouault's Christ is depicted standing with his head and eyes down and his eyes shut. His face shows pain though he remains impassive. Rouault would return later in his career to the iconography of Christ's silent suffering since, for him, the only salvation for humanity was Christ.

Illustrated book with 58 aquatints on Arches laid paper - Plate 3. "toujours flagellé" ("forever scourged")

Pierrot

Pierrot is one the most famous character of the Commedia Dell'Arte and had been very popular in the French pantomime tradition since the 18th century. This middle-to-late period clown is part of a career-spanning series produced by Rouault featuring the figure of Pierrot. For him, the sad clown initially symbolized human weakness and vulnerability; a state of false hopes and unfulfilled dreams. However, the somber character and sad look of Rouault's early clowns would give way to a more serene theater character. Here, the colors are bright and warm with both the stage and the figure treated on the same hues of white and red. The artist's characteristic black bold lines delineate the colors in a Cloisonnist way which was typical of Rouault's mature style; it takes the viewer back in fact to the art of the stained glass while the flattening of the image situates the painting firmly within the realm of modernity.

All of Rouault's Pierrots have this same elongated face and straight nose. The figure here seems quite peaceful with a slight smile and the eyes remain closed. If Pierrot is often said to be an alter ego of the artist, here, this whimsical, thoughtful and serene clown could evoke Rouault's own, newfound peace in the mid-1930s. "I spent my life painting twilights", Rouault reflected at the time, "I ought to have the right now to paint the dawn". Lionello Venturi added: "When he paints clowns, the grotesque becomes amiable, even lovable [...] colors grow rich and resplendent, almost as if the artist, laying aside his crusader's arms for a moment, were relaxing in the light of the sun and letting it flood into his work".

Oil on canvas - Museum of Fine Arts, Boston

Head of Christ

Using simple, strong black lines, Rouault painted many portraits of Christ in this style. Blends of warm and subdued colors separated by heavy lines emphasize the face of Christ who is also surrounded by a hazy halo of light. Using realistic flesh-tones, the painting is a profoundly human image of Christ. The expression of the eyes is particularly striking, and, when taken with the slightly tilted position of the head, reinforces the depth of Christ's wisdom.

Rouault does not seek to represent an omniscient and omnipotent God in his Christ. Through this portrait, he conveys Christ as a (the) paragone of empathy and compassion. His naked flesh tones coupled with his sincere expression represent Christ as a man who experienced all the pain (and more) of the human condition. In this sense, Christ may be compared to all the outcasts depicted by Rouault throughout his career. Clowns, entertainers, Pierrot himself, and prostitutes become figures of Christ in effect. But, for the devout artist, Christ is the ultimate redeemer. His look here is penetrative but not punishing, and the calm expression of the face offers a path to love and forgiveness.

Oil on canvas - Cleveland Museum of Art

Biblical landscape with two trees

At the end of his life, Rouault painted a series of landscapes usually titled Biblical Landscapes or Landscapes with Figures. Typical of these late works, this painting is composed with an architectural structure in the background and unidentified figures populating the foreground. The characters here are in the very center of the picture framed by two trees (that are also mentioned in the title). Painting from his imagination, Rouault carefully builds the space of this landscape to support the figures. The sun is omnipresent in all these late paintings and illuminates the composition (as it does here). Dominated by warm dark brown and green, Rouault uses pure colors, flattened figures, and heavy black outlines.

Inspired by his own faith, each of his landscapes displays an atmosphere of calm and serenity. The clothing indicates ancient times, and although the title does not reference a specific Biblical story, the figures may very well be Jesus accompanied by followers. With a simplicity of means, the artist looks back to symbolic landscapes and combines his search of pure colors with more classical influences. Via these means Rouault lends his scene a typically deep spiritual dimension that marked him out as unique amongst his peers. Earlier in his career the poet and critic André Suarès prompted in a review of Rouault's work, "never smother the mystical song that rests deep inside you" - it was advice he heeded throughout his whole creative life.

Oil on paper mounted on canvas - The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York

Biography of Georges Rouault

Childhood

Georges-Henri Rouault was born in a cellar on May 27, 1871 during the tumultuous "Bloody Week" at the end of the Paris Commune. A stray shell struck the family home and the young expectant mother had to be moved into the cellar where she gave birth to her second child.

A frail little boy, Rouault spent a happy childhood in the working area of Belleville in Paris. His father, Alexander, was a carpenter employed in the Pleyel piano factory, and he soon became heir to his father's love of craftsmanship. Rouault's whole family shared an interest in creativity and encouraged Georges's love for art. Indeed, his grandfather (on his mother's side) had built up a collection of Honoré Daumier's lithographs and reproductions of paintings by Rembrandt, Courbet and Manet and Rouault would later comment that he went to school first with Daumier.

Early Training and Work

Rouault began to draw at an early age and by the age of fourteen he was working as an apprentice to a glass painter and medieval windows restorer named Georges Hirsch. This early life experience is often said to be the source of the heavy black lines that characterize Rouault's mature style. Even after a long day at work, he would walk to the other side of Paris to draw from antiques and from life at the School of Decorative Arts. He would also spend Sundays at the Louvre making sketches.

Aged eighteen, Rouault enrolled in the School of Fine Arts in Paris. Like Matisse, Marquet and Camoin, he studied under the renowned Symbolist Gustave Moreau. Rouault soon became his Master's favorite pupil and his personal friend. Moreau was a progressive, open-minded tutor who conscientiously cherished and respected the unique personalities of his students and would always strive to give his pupils the space to develop their individual artistic predilections.

Numerous works from this period display the influence of Moreau on the young Rouault who fantasized about winning the famous Prix de Rome. In 1894, Rouault won the Prix Chenavard but failed in his attempt to win the more coveted Prix de Rome. After that failure (twice), Moreau himself advised his mentee to drop out of school and to continue his career independently. Rouault left the school but Moreau continued to encourage him. Indeed, the pair formed a strong bond and Rouault would usually adhere to his mentor's advice. Still in his early twenties, Rouault started to contribute annually to the Salon des Artistes Française. He also began to visit the Ambroise Vollard gallery where he saw works by artists of the calibre of Cézanne and Gauguin.

The sudden death of Moreau in 1897 devastated Rouault. Around the same time, his parents moved to Algeria to support his sister whose husband had passed away. Despite being entrusted and appointed Curator of the Moreau Museum in 1898, Rouault fell into a deep depression. He endured a violent crisis and a long period of solitude and sorrow that he called his "abyss". He stopped painting for a while. "It was then," he commented later, "that I learned the truth of Cezanne's famous words, 'Life is horrifying'".

In 1901, Rouault decided to spend some time at the Benedictine Abbey of Ligugé where his friend, the novelist Huysmans, wanted to create a secluded community for Catholic artists. The artist had converted to Catholicism in 1895 and was close to the French Catholic intelligentsia of the time. At Ligugé, the group agreed to resist publicity and everything that flattered their creative vanities. Rouault, indeed, resolved never to pander to public taste. The passing of the so-called Waldeck-Rousseau law against religious associations in 1902 led to the dissolution of the community and Rouault returned to Paris. Later that same year, he spent some time in the resort area of Evian-les-Bains where he finally recovered his equilibrium. He resumed painting with a renewed vigor and reflected: "I underwent a moral crisis of the most violent sort. I experienced things which cannot be expressed by words. And I began to paint with an outrageous lyricism which disconcerted everybody".

Inspired by Moreau's ideas and his own philosophical and religious beliefs, Rouault developed a highly individual expressive style, and picked subject matters that reflected his personal mistrust of the corruption and complacency of bourgeois society. He would soon abandon Moreau's symbolism and directed his attention to the display of human misery. He started to haunt law courts and began depicting corrupt judges in a Daumier-like style. With some fellow-artists, he asked prostitutes to come to his studio to paint them. His fascination with outcasts and entertainers such as clowns, acrobats, jugglers and dancers helped him to experiment with form and color, while ruminating thematically on human misery and loneliness.

His well-known attraction to clowns started as early as 1905 when the artist happened to witness a scene that would mark his vision of life. While out walking one day, the artist came across a "nomad caravan, parked by the roadside". It was a circus, preparing for its next public performance. Rouault's eye fell upon one of the figures: an "old clown sitting in a corner of his caravan in the process of mending his sparkling and gaudy costume". The artist was intrigued by the contrast between the clown's "scintillating" costume and ostensibly happy demeanour, and his private life "of infinite sadness" which he saw reflected in all people: "I saw quite clearly that the 'clown' was me, was us, nearly all of us [...] We are all more or less clowns" he concluded.

Inspired by his observations on everyday reality, Rouault imbued his paintings with human experience. His output at that time is characterized by the violence of the drawing and the dynamism of the line. In a heartfelt reaction against academicism, he had already taken part in the creation of the progressive Salon d'Automne of 1903. He would soon participate himself, notably in the 1905, when he exhibited with to the Fauves and Matisse. He was indeed an affiliate of the Fauvists and experimented himself with pure color, form and composition. Matisse and Rouault shared a fruitful working relationship as testified to in their long correspondences. Moreau had been central to both men's artistic development. Color was central to both men's aesthetic but, unlike Matisse, Rouault added bold heavy lines to his jewel-like tones and drew on his Catholic faith for his subject matter.

Rouault was a taciturn man who seldom visited cafes and never really participated in the Bohemian life of Paris, preferring to stay closer to Catholic circles. He had by this time discovered the writings of the radical and polemical Catholic Leon Bloy and he embraced the ideas of a writer who preached spiritual revival through suffering and poverty. Bloy was, however, known for his bigotry and bad temper and he hated Rouault's paintings which he found ugly. Nevertheless, the two men remained close friends until the writer's death in 1917. The painter was particularly struck by the novel La Femme Pauvre. The book follows the miserable life of a woman named Clotilde who, animated by her strong faith, is able to endure all her sufferings. Rouault was deeply inspired by the book and based some of his characters on Clotilde. He introduced Bloy to painter George Desvallieres who had been Moreau's pupil as well and a founder of the Salon d'Automne. After meeting with Bloy, he became, like Rouault, a militant and engaged Christian artist who championed avant-garde art. The two artists would in fact share a friendly working relationship for many years to come. In 1908, Rouault married Marthe Le Sidaner, a pianist and the sister of the painter Henri Sidaner. They would remain married until the end of his life, raising four children together.

Mature Period

Rouault started to gain some recognition in the art world during the 1910s. Heavier forms outlined with thick black lines and oils began to appear in his painting in this period. He also started to experiment with other media, especially engraving. In 1910, Druet gave him his first solo show, yet despite this early success, the artist cut a poor, solitary figure. The humble income from his steady job at the Moreau Museum was not enough to sustain the whole family and in 1912 the Rouault family moved to Versailles where they lived in a squalid, rat-infested, house in an old quarter of the town. Within a few days of arriving in Versailles, Georges's father, with whom he had had long discussions on the nature of art, died. This was yet another shattering blow for the painter and he found comfort in the company of Jacques Maritain, another member of the Catholic revival movement. Maritain was a respected philosopher who had converted to Roman Catholicism in 1905 (having also fallen under the influence of Bloy). This period proved a turning point for Rouault's whose art would become more and more Catholic in its outlook.

Unable to lessen the pain from his father's passing, Rouault started a series of Indian ink drawings, which would eventually serve as the base of the engravings of his monumental masterpiece, the Miserere book. Rouault would have to wait until 1948 to see this project reach fruition when the book was published with a total of 58 engravings. The initial drawings were all based on the 50th Psalm of Repentance in Catholic liturgy, Miserere mie Deus, but Rouault was also influenced by the horrors of World War I, and his own concern for the marginalized in society.

During WWI, the artist was declared unfit for service. The whole family moved to the country in Normandy where Rouault was still able to paint in relative peace. The image of Christ would become more and more prevalent in his output and in 1917 Rouault signed a contract with art dealer Ambroise Vollard. The artist had known the dealer for many years and had started to discuss their terms as early as 1913. Rouault finally decided to give Vollard artistic exclusivity in return for a fixed salary; the dealer even made a studio available on the top floor of his own house where Rouault was able to work at his own pace. Rouault had achieved financial peace of mind and was now able devote all his energies towards his career. However, Vollard was known to be a jealous and controlling patron who liked to monopolize the work of his artists.

Vollard loved books and prints too and commissioned many illustrated books from Rouault. Vollard became more and more demanding and the artist painted less and less, concentrating more on printmaking. He illustrated several book during this period including the sequels to Pere Ubu by Alfred Jarry (1927) and the Fleurs du Mal by Charles Baudelaire (1928). In 1928, Rouault and his "brother in art", the poet and critic Andre Suares, had completed a book project on which they had worked together for several years. Vollard, who harbored a petty grievance against the poet, refused to publish Suares's writings. Though frustrated, Rouault agreed to replace Suares's poetry with his own writings, naming the finished book The Circus of the Shooting Star.

Despite his forays into printmaking, Rouault, from the period of 1927-8, committed to paint only in what would become his signature style: heavy black lines encircling colors and shapes. He took the decision to use only oil, abandoning watercolor and gouache altogether. Clowns, prostitutes, but also the figure of Christ, dominated his work. His Catholic worldview had grown stronger over the year and brought to his output an even highly spiritual dimension. As scholar William Dyrness stated: "Rouault searched to paint the archetype of the human condition in the figures of clowns, prostitutes and lower-class people who are to be ameliorated by family solidarity or the presence of Christ".

During his mature period, Rouault participated in many exhibitions and these proved relatively successful with the critics. In 1929, he designed the décor and costumes for the ballet The Prodigal Son for his friend Sergei Diaghilev and in 1937, Rouault gained worldwide recognition when he presented forty-two paintings at the Paris World's Fair. Outside of France, meanwhile, Matisse's son, Pierre, would give Rouault three solo exhibitions at his gallery in New York between 1933 and 1947.

Late Period

In 1939, Vollard was killed in a car crash and Rouault found himself suddenly released from his contract with his dealer. However, Vollard's estate sealed the entrance to his house preventing Rouault from retrieving his sketches, notes, and unfinished artworks. World War II had forced Rouault to leave Paris for the south of France long before the matter was resolved. Once in the south, however, he joined other displaced artists and continued to paint.

It is not until 1947 that Rouault was able to finally settle his legal case against the Vollard estate. He had successfully sued Vollard's heirs for the return of some 800 paintings, claiming that they were unfinished and that his reputation as a painter would be damaged by their sale in an unfinished state. The court decided that the painter was the rightful owner of his own paintings - "provided that he had not given them away of his own volition" - and he secured the return of over 700 unfinished paintings. A year later, before a public notary, Rouault burnt 315 unfinished works that he felt he could no longer complete. He would burn more works a few years later. For the artist, it seems, the trial was a moral more than a material triumph.

Happy and contended, warmer tonalities began to appear in his paintings. The final ten years of his career are characterized by brilliant colors, less earnest pictures, and the return to landscapes. He would experiment with colors until the end of his life. Finally in 1949, the Catholic Church commissioned windows from him for the church at Plateau d'Assy, in Haute-Savoie, France. By 1956 Rouault was too frail to paint and in 1958, he died at the age of 87. He became the first artist in history to be given a state funeral by the French government. In 1963, his family donated almost 1000 unfinished works to the French State.

The Legacy of Georges Rouault

Rouault holds a special place in the history of modern art. He was contemporary of the Cubists, Fauvists and Expressionists without ever joining their ranks. He developed a highly individualistic style but because he was a passionate Catholic, and often depicted religious themes, he was never fully accepted as a modernist artist. Clement Greenberg had dismissed him by saying in 1945: "That Rouault, pictorial exponent of the pornographic, sadomasochistic, 'avant-garde' Catholicism of Léon Bloy, should be hailed as the one profoundly religious painter of our time is one of the embarrassments of modernist art". He was mistrusted both by modernists, who found him too conventional, and by religious writers who found his religious sensibilities not traditional enough.

Rouault's legacy only started to be reevaluated in the 1980s. Today, critics tend to consider him more as an artist who demonstrated an unique ability to marry modernist experimentation with faith and spirituality. His friendship with ambiguous radical catholic figures has also been recontextualized in 20th century France. More emphasis is given to Rouault's commitments to social and political issues and to the plight of marginalized groups. His long trial also set a precedent in the history of ownership and copyright in France. The legislation was favorable to the artist and mandates that an artist owns his or her art.

Interestingly, Rouault's work is greatly appreciated in Japan. He is revered by Japanese calligraphers who celebrate his lines, comparing him with the greatest Chinese calligraphers. One Zen master even said: "Rouault's lines contain the weight of life". Japanese artists look beyond his subject matters and focus on Rouault's mastery of drawing and on his profound spirituality.

Influences and Connections

-

![Henri Matisse]() Henri Matisse

Henri Matisse - Leon Boy

- Jacques Maritain

- Maurice Girardin

- Religious and Sacred Art

- Shirakaba

Useful Resources on Georges Rouault

- This Anguished World of Shadows: George Rouault's Miserere et GuerreOur PickBy Holly Flora

- Rouault in PerspectiveOur PickBy Soo Yun Kang

- Georges Rouault: The Inner LightBy Ileana Marcoulesco

- Georges Rouault: The Early Years 1903-1920Our PickBy Fabrice Hergott and Sarah Whitfield

- Georges Rouault: Illustrated Books. Catalogue RaisonnéBy Francois Chapon

Ask The Art Story AI

Ask The Art Story AI