Summary of Rachel Ruysch

Ruysch was a Dutch painter who, with Jan van Huysum, is the most celebrated exponent of still lifes and flower pieces to emerge during the Dutch Golden Age. She painted elegant bouquets and dark forest flora with such attention to detail, and such delicacy of colour, they are considered amongst the very finest pieces in the long tradition of Dutch still life painting. A successful and celebrated artist in her own lifetime, she was the first female member inducted into The Hague's painter's society, was then appointed court painter to the Elector Palatine in Düsseldorf and accepted many prominent commissions from international patrons (including Cosimo III de' Medici). Ruysch remained artistically active throughout her long life and proudly inscribed her age (83) on of one her last canvases.

Accomplishments

- As a mother of ten children, Ruysch bore considerable domestic responsibilities. Yet in addition to her role as care provider and homemaker, she was a prolific painter, producing over 250 works in a seven-decade career (an extra impressive output when one takes account the concentrated level of detail in her pictures). Her art brought her widespread international and domestic acclaim. In the Netherlands she was known affectionately as Hollants Kunstwonder ("Holland's art prodigy"), Onze vernuftige Kunstheldin ("Our subtle art heroine"), and the Onsterflyke Y-Minerf ("Immortal Minerva of the Amsterdam").

- Such was its naval power, the Netherlands became the dominant force in global commerce during the second half of the seventeenth century. This new age of prosperity provided the backdrop for the famous Dutch Golden Age of painting. Ruysch's art is indicative of the phenomenon that became known as "tulip mania". Her paintings spoke to the Dutch people's love of rare, imported flowers (such as the Turkish tulip) that were valued above other commodities for their natural beauty and fragrance.

- Ruysch's painting showed an exquisite attention to picture realism with flora details - stems, leaves, petals and so on - that are scientifically exact. She was remarkably skilled at capturing textures, from fragile petals to brittle leaves. Moreover, Ruysch depicted insects, reptiles and small mammals - crawling caterpillars, pollen gathering bees, dragonflies, and the like - with the same artistry and precision.

- Although she was celebrated for her dedication to life-like detail, many of Ruysch's compositions were conjured from her imagination. She often brought together flowers, plants, and animal life that would never be found together in nature. Dutch floral artists of the period typically arranged flowers according to type, but Ruysch's more "haphazard" and dramatic Baroque compositions stand out as a reaction to lighter floral paintings that were painted in the more usual Mannerist style.

- In the Netherlands during the sixteenth and seventeenth century, artistic genres were divided into two categories: "greater" and "lesser". The former accounted for historical and religious themes; the latter, still lifes, portraiture and landscapes. But Ruysch (and Rembrandt for that matter) did more than any other to elevate the credibility of "lesser" genres. She emerged as one of the greatest flower painters (of either sex) and her success provided inspiration to other female artists including Clara Peeters, Judith Leyster, Michaëlina Woutiers, and Maria van Oosterwijck.

The Life of Rachel Ruysch

Germaine Greer wrote in The Obstacle Race, "[Ruysch's] taste in choosing and balancing blooms, colours, light and backgrounds was perfect", while adding that "the finish of her painting [was] soft, clear and flawless".

Important Art by Rachel Ruysch

Insects and Lizard in a Wood

In this work, typical of Ruysch's early years, we see a section of dark forest floor painted in dark browns and greens. On the right-hand side, a green, leafy plant, stands illuminated by natural light. Surrounding it are flying white and orange butterflies and moths, and a green lizard at its base. This type of painting is referred to as sottobosco, or "forest floor" painting, and Ruysch drew inspiration for her early sottobosco works from Otto Marseus van Schrieck, Abraham Mignon, and her teacher, Willem van Aelst.

A technique she adopted was the use of real moss, and sometimes even butterfly wings, to directly apply paint, creating the painted surface with a real sense of texture. After her main compositions had been painted and dried, Ruysch then used fine brushes to add the details, including slender blades of grass, tiny flowers, and creatures (like the insects and lizard in this work) that populate the microcosms created within each of her works. Arts writer Alexxa Gotthardt explains that Ruysch "swiftly gained a reputation across Amsterdam for the enchanting realism of the plants and insects that filled her paintings; they weren't idealized, but rather alluded to mortality and the life cycle".

Art historian Barbara Morgan writes, "In her earliest works, Ruysch closely followed the dramatically lit woodland scenes of the Dutch painters of the previous generation [specifically van Schrieck and Mignon]. Ruysch depicted forestal vignettes complete with small-scale creatures. Characteristically, Ruysch repeats Schriek's motif of the lizard with a butterfly perched in its open mouth, but minimizes the menacing import of such a creature by reducing its scale and by relegating it to the fringe of the composition". In this way, her paintings are often understood as sorts of vanitas or memento mori, that is works that remind the viewer of death and the fleetingness of existence. As art historian Lynn Robinson put it, "Wealthy Dutch consumers were being reminded to not become too attached to their material possessions and worldly pleasures; eternal salvation came only through devotion to God".

Oil on canvas - Fitzwilliam Museum, Cambridge, England

Roses, Convolvulus, Poppies and Other Flowers in an Urn on a Stone Ledge

Morgan writes that, "Ruysch practiced her art in the Baroque period of art history. Baroque art was a style that arose in Europe [...] as a reaction against the Mannerist style, an intricate and formulaic approach that dominated the late Renaissance period [whereas the] Baroque style was less complex and more realistic". She notes that flower painting became a key feature of late 17th century Baroque art and that "factors influencing its emergence included the growing and more affluent merchant and middle classes, as well as the growing interest in plants that resulted from the developing science of botany".

In this work, a pyramid-shaped bouquet of colorful flowers sits in a short, rounded terracotta vase on a windowsill. The inclusion of an architectural feature in flower paintings was a popular trend in the Netherlands at the time. As is typical of her earlier paintings of bouquets of flowers, the composition is tightly focused, compact, and clearly defined. As in many of her works, closer examination reveals a multitude of insects fluttering and crawling in and among the flowers, which include peonies, roses, nasturtiums, foxgloves, and more (all painted in near microscopic detail).

Indeed, perhaps the most striking feature of Ruysch's oeuvre is the inclusion of entire ecosystems within a single work (and not just in her outdoor sottobosco works, but in her indoor bouquets as well). It was between 1660-70 in Northern Europe that the microscope was improved upon significantly and used widely by scientists to study biology. It gave rise to a widespread interest in identifying, cataloguing, and categorizing the natural world. Ruysch no doubt developed this interest during childhood, watching her father carefully curate his cabinet of curiosities, and the dioramas he made from the specimens in is collection. Her paintings treat each plant, insect, and animal as a scientific specimen, while blending these objects into a beautiful compositional harmony.

Oil on canvas - National Museum of Women in the Arts, Washington D. C.

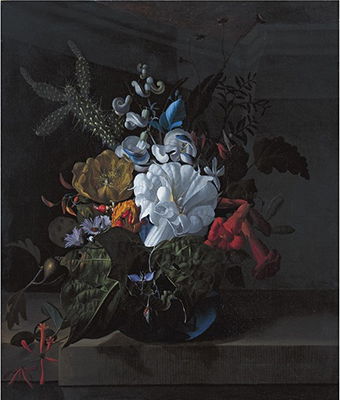

A Still Life with Devil's Trumpet, a Cactus, a Fig Branch, Honeysuckle and Other Flowers in a Blue Glass Vase Resting on a Ledge

This work features a mixture of flowers and other plants in a vase, against a dark architectural background. It exemplifies the way in which Ruysch used her "artistic license" to combine plants and flowers that would never appear together in the natural world. As art historian Marsha Meskimmon notes, Ruysch's fusion of "exquisite realism and imaginative composition" was innovative, as it neither "conformed simply to the predominant conventions of allegorical floral still-life in the period nor to those of scientific illustration, yet participated in both". As an added note of interest, Ruysch was thought to be the first Western painter to include cacti in still life paintings (seen here in the top left of the frame).

A Still Life with Devil's Trumpet has an overall cool, bluish hue, creating the sense that the bouquet is being studied under laboratory lighting. Moreover, in this, and many other works, Ruysch placed her bouquets in transparent glass containers, reminiscent of the glass beakers and jars that her father would have used to house his organic specimens. Even the way in which Ruysch presents single plants from multiple angles indicates the creative mindset with which she approached flower painting. Morgan writes that "Ruysch was known for these lively and informal looking arrangements. The flowers are asymmetrically arranged [...] Light alternates with shadow, enlivening the flowers as they stand out dramatically against the darker background".

Oil on canvas - Private collection

Still-Life with Fruit, Flowers, and Insects

This work, painted for Cosimo III de' Medici, the grand duke of Tuscany, features a bounty of fruits and vegetables typical of the autumn harvest. It includes grapes, corn, peaches, and wheat, all sitting out-of-doors on a bed of moss. A small bird's nest filled with eggs sits at the bottom left, and insects, a lizard, and a snail are also present in the scene. Not only does this painting demonstrate Ruysch's technical virtuosity in terms of representing natural objects in perfectly realistic detail (note, for instance, the velvety texture of the peaches and the misty sheen of the grapes), but also her keen eye for color, as seen in the joyous balance of reds and greens. This work highlights the agricultural richness and plentitude of the Tuscan region, by showing off the wide variety of crops yielded in the area. However, religious significance can also be read into the work, with the grapes and wheat symbolizing the bread and wine of the Eucharist.

Some historians read Ruysch's paintings in the form of vanitas and that works such as this represented the Christian doctrine that all beauty withers and that all organic life, in the end, must die. Ruysch's paintings celebrated the beauty and luxury of harvest foods and botanical life, but vanitas were ultimately a reminder of the fleeting nature of organic life. Although they do not qualify as devotional pieces, the underpinning message was universal: "eternal salvation comes only through devotion to God".

Oil on canvas - Uffizi Gallery, Florence

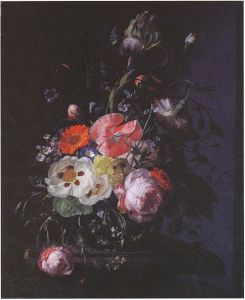

Flowers Still Life

Flowers Still Life presents a bouquet of mostly white and pink (with some blue) mid-summer flowers in a vase, against a very dark stone ledge, with creatures including a bee, a caterpillar, and a butterfly hidden within the composition. As art historian Lynn Robinson notes, it is an excellent example of the "complex", "lively", and "informal" arrangements for which Ruysch was known and which stood her apart from the more formal painters of her time. Ruysch employs sweeping diagonals and dramatic curves, drawing the eye dynamically around the image. Art historian Barbara Morgan observed that Ruysch had adopted Abraham Mignon's practice of placing cultivated plants in natural settings, but she shied-away from his liking for Christian symbolism (such the goldfinch) by focusing on decorative effect over iconography.

Later in her career, Ruysch's favored more open, sprawling, and frame-filling arrangements, around which she suggests a greater sense of atmosphere and moisture. Curator Lawrence W. Nichols comments upon the way in which, "the artist placed in the center the brightest and lightest flowers and endowed depth to the arrangement through darker tones at the edges. Such attention to aesthetic details and formal devices attests to Ruysch's remarkable technique, as well as to her skill at artifice". Morgan adds that "Against the dark background, the flowers seem almost revealed in a photographic light. In this way, her works were similar to paintings done by eighteenth-century artists such as Jan van Huysum, Jan van Os and Johan Christiaan Roedig. In fact, with her innovative techniques, Ruysch employed a style that can be seen as a transition from 17th-century to 18th-century flower painting".

Oil on canvas - Toledo Museum of Art

Biography of Rachel Ruysch

Childhood

Rachel Ruysch had a unique upbringing which saw her raised in an environment of art and science. One of twelve siblings, she was born to Frederik Ruysch, an eccentric anatomist and botanist, and Maria Post, whose father (Rachel's grandfather) was the renowned imperial architect Pieter Post, and whose brother (Rachel's great uncle) was the leading landscape painter, Frans Post. They were a prominent and wealthy family who relocated from The Hague to Amsterdam, where they lived on Bloemgracht (the "flower canal"), a popular location for visiting artists. Frederik took up the position of Amsterdam's praelector (college officer) of anatomy in 1667, and later professor of botany at the city's botanical garden.

Frederik collected a variety of unique natural specimens - plants, animals, insects, human body parts - for his cabinet of curiosities, which occupied five whole rooms of their home. He had developed a new method of embalmment, which allowed him to preserve organic matter in a seemingly natural state. Indeed, Ruysch's father was famed for his cabinet curiosities and would artfully pose his collection of embalmed and wax-injected organs, animals, plants, and body parts in macabre dioramas (such as a severed child's hand and forearm hand holding a hatching turtle egg). Frederik would proudly present his curious Memento Mori (death mementoes) to invited foreign visitors and young Rachel enjoyed drawing these objects, which she learned to do with a high degree of accuracy. Her drawings were used by Frederik (himself a competent draftsman) for cataloging purposes.

Frederick was an admirer of Otto Marseus van Schrieck, a painter from Nijmegen, who had served at royal courts in France and Tuscany. He was well known for his paintings of reptiles and insects who populated the world of plants, shrubs, moss and fungi. In Italy this style of forest floor painting was called sottobosco (or bosgrondjes, in the Netherlands). On the event of van Schrieck's passing (in 1678) Frederik acquired several of his paintings as well as numerous insect specimens. Rachel scrutinized these artworks, and her earliest paintings demonstrate van Schrieck's influence.

Although he was himself a decent enough draftsman, the art historian Marsha Meskimmon notes that it is vital not to overlook the importance of Rachel's influence on her father's drawings: "published images were a crucial means of disseminating scientific knowledge throughout Europe in the period and Rachel's contribution to this facet of Frederick's practice was quite valuable [...] visual exchanges between anatomical cabinet and still-life painting developed, both laden with symbols for moral contemplation while also presenting specimens for detailed observation".

Education

When she was fifteen, Frederik permitted his daughter to be apprenticed to renowned flower and still life painter Willem van Aelst, whose Amsterdam studio looked out over the studio of flower painter Maria van Oosterwick. Ruysch studied with van Aelst for four years (until his passing). He not only taught her to paint, but also to arrange flowers so that they would look less contrived. The art historian Barbara Morgan writes, "[Van Aelst] was famous for creating elaborate still-life paintings that featured spiralling compositions and eschewed the convention of symmetrical arrangements of depicted bouquets. [His] somewhat irregular approach translated itself into the works of his pupils. Among them were Ruysch, [Ernst] Stuven, and Ruysch's younger sister Anna Elisabeth, who also became an artist of recognized merit, although she never attained the stature of her more determined sister". By the age of eighteen, Ruysch was already making a name (and living) for herself while rubbing shoulders with the city's most popular flower painters and horticulturists.

Mature Period

The chance to study and develop her own painting career set Ruysch apart from most women of her time. While her choice to paint flowers and still lifes was deemed "appropriate" subject matter for women artists, still life painting had grown in popularity as a genre. As historian Lynn Robinson states: "In 1648, the Netherlands became independent from Spain, ushering in a period of great economic prosperity. Flourishing international trade and a thriving capitalistic economy resulted in a newly affluent middle class. Wealthy merchants created a new kind of patronage and art market. Without a powerful monarchy or the Catholic Church to commission artworks (the Dutch were Protestants), artists produced directly for buyers. Like today, buyers purchased art either from professional dealers or from the artist in their studios. Subjects like big historical, mythological or religious paintings were no longer desired; buyers wanted portraits, still lifes, landscapes and genre paintings (scenes of everyday life) to decorate their homes. Proud of their newly independent country and trade wealth, they desired artworks that would reflect their success".

Ruysch's career ran parallel to the growth of the country's burgeoning horticultural industry and a fervent interest in the science of botany. Robinson writes that the Netherland's became "the largest importers of new and exotic plants and flowers from around the world". Where previously valued by the markets for their medicinal uses, flowers became desirable commodities highly prized for their simple beauty and fine fragrance.

Botanists and gardeners sought the rarest specimens imported from overseas trade and tulips - "coveted for their intense and unusually varied colors" - were prized above all others. (Imported initially from Turkey in the late sixteenth century, the Netherland's had recently experienced a period referred to as "Tulip Mania". Robinson writes that "Tulip bulbs were so avidly desired in 17th century Netherlands that [...] Buyers bought bulbs still in the ground, speculating that they would be worth more in the future and could then be sold for a large profit. However, in 1637, "investors suddenly decided that tulip bulbs were grossly overpriced [...] Prices plummeted, tulip bulbs lost 90% of their earlier value, and the market crashed. The world had just experienced its first financial bubble".)

In 1693, Ruysch married the successful portrait painter (and adopted son of Mignon), Juriaen Pool. The couple would go on to have ten children. Despite being more than occupied with her domestic situation (and even if the family's status suggested they were very likely to have had hired domestic help), Ruysch continued to paint, producing over 250 paintings over seven decades. Her painting career brought in steady income for the family, with Ruysch earning, on average, more per painting during her lifetime than even Rembrandt. As Morgan writes, "Ruysch's work found a receptive audience and contemporary writers praised her extensively. Such esteem was admirable for any painter, but especially so for a woman. As Johan van Gool wrote in 1750, her artfulness 'was all the more astonishing and to be praised in women, who by nature are destined to other occupations'. Despite such gendered trepidations, Ruysch earned international renown for her expertly wrought and pleasingly arranged creations".

Ruysch became a member of "independent" Confrerie Pictura society between 1701-08, and, in 1709, she achieved the honor of becoming the first female member of The Hague's artist's society, The Guild of St. Luke (the very society to which members of Confrerie Pictura had been opposed). Between 1708 to 1716, she served as court painter to Johan Willem, Elector Palatine of Bavaria, who resided in Düsseldorf. It was at the elector's court, writes Morgan, that "she began to employ the newly discovered pigment Prussian blue, an inexpensive means of summoning luminous blues. Similarly, Ruysch utilized a smooth touch to craft crystal-clear surfaces".

Ruysch's youngest child, a boy, was born when she was 47 and she decided to call him Jan Willem in honor of Palatine, and who, with his wife, agreed to act as the boy's godparents. When Ruysch travelled to Düsseldorf to introduce them to their godchild, Johann Wilhelm presented him with a valuable medallion on a red ribbon while Ruysch was gifted a 28-piece silver toilet set in a decorative toilet case featuring six decorative silver sconces.

Late Period

It is widely believed that, while court painters were expected to relocate, Ruysch commanded such respect she was permitted to stay with her family in Amsterdam. This view is, however, contradicted by Morgan who states that the family did in fact move to Düsseldorf where they lived between 1708-16. In either case, Ruysch continued to paint for both the Elector and many wealthy Dutch patrons during her tenure as court painter. Morgan writes in fact that, "When Ruysch and Pool returned to Amsterdam in 1716, Ruysch brought her aristocratically fostered aesthetic with her and continued to paint elegant still lifes such as Still Life with Flowers on a Marble Table Top".

Now settled permanently in Amsterdam, Ruysch accepted commissions from many prominent domestic and international patrons, including Cosimo III de' Medici, and, according to historian Dániel Margócsy, refused "to adapt [her] work and personal identity to the desires of a particular patron".

In the spring of 1711, Ruysch was visited by a German scholar, Zacharias Conrad von Uffenbach. She had recently completed paintings for Pieter de la Court van der Voort, a cloth merchant from Leiden (who paid Ruysch the princely sum of 1,500 guilders; a stipend many times greater than the average annual salary). Von Uffenbach commented enthusiastically on the "exceptionally delicate brushwork" and noted that while working on two small square panels for Cosimo de' Medici, she had surrounded herself with "all kinds of birds' nests, insects and suchlike".

Juriaen had been commissioned by the Elector to paint his wife's portrait, though he turned it into a family portrait, painting Rachel and himself with Jan Willem presenting his mother with the medallion he had been given by the Elector (his godfather). The painting was completed in 1716 as news broke that the Elector had died. Although Ruysch had lost her most important patron, she was still kept busy with commissions. The family was well off (they had already won two hundred guilders on the lottery in 1713) but in December 1722 they bought a ten-guilder lottery ticket that won the first prize of 75,000 guilders. The family's good fortune was offset with tragedy, however, with the loss of seven of their teen and early adult aged children by 1731.

In 1750 Ruysch's life was celebrated by the state with the collection "Dichtlovers voor de uitmuntende schilderessen Mejufvrouwe Rachel Ruisch" ("Poems for the excellent painter Mistress Rachel Ruysch"). It was an anthology, the first of its kind for a Dutch artist, that brought together verse by eleven contemporary poets who celebrated her life and works. Rachel Ruysch died later that year, she was 85 years old.

The Legacy of Rachel Ruysch

Ruysch established herself as the preeminent painter of flowers, capturing, and indeed immortalizing, the beauty of, what were to the new Dutch Republic, perishable luxury goods. Today art historians laud her as one of the most important still life painters - male or female - in the history of the genre. Although flower painting became unfashionable soon after her death, Ruysch's legacy was carried forward by Jan van Huysum, now regarded as the last of the great Dutch still life painters. Moreover, Ruysch takes her place in the pantheon as one of the few women of the Dutch Golden Age, placing her in the company of other accomplished women artists of the period, including Judith Leyster, Clara Peeters, and Maria van Oosterwyck.

Morgan writes, "Her paintings were more than just realistic and scientifically accurate depictions. Ruysch possessed excellent skill and technique [...] She used form, color and textures in ways that were innovative, bold, and dynamic". She adds that Ruysch's "open, diagonal compositions contrasted with the more compact and symmetrical arrangements than those of the other early 17th century women painters". Her compositions were more asymmetrical "loose" and "spontaneous" than those of her peers but that this "informality was carefully designed to achieve the ultimate effect. The end result was that her works possessed more energy and created the illusion of immediate realism", so much so, that a viewer of her paintings "could almost reach out and touch her bouquets".

Influences and Connections

- Otto Marseus van Schrieck

- Willem van Aelst

- Maria van Oosterwijck

- Johan Christiaan Roedig

- Abraham Mignon

- Juriaen Pool

- Jan Moninckx

- Maria Moninckx

- Alida Withoos

- Johanna Helena Herolt-Graff

- Jan van Huysum

- Jan van Os

- Johan Christiaan Roedig

- Juriaen Pool

- Jan Moninckx

- Maria Moninckx

- Alida Withoos

- Johanna Helena Herolt-Graff

Useful Resources on Rachel Ruysch

- Eighteenth Century Women Artists: Their Trials, Tribulations and TriumphsBy Caroline Chapman

- The Obstacle RaceBy Germaine Greer

- Women Artists: 1550-1950By Ann Sutherland Harris and Linda Nochlin

- Women ArtistsBy Susan Sterling Fisher

- Women ArtistsBy Margaret Barlow

Ask The Art Story AI

Ask The Art Story AI