Summary of Augusta Savage

The sculptor Augusta Savage was one of the foremost female African-American artists of her generation. Her work played a major role within the Harlem Renaissance during the first half of the twentieth century. Best known for her small portrait sculptures, Savage rendered her subjects in a considered and compassionate way. Her iconic busts helped immortalize key civil rights personalities, while her portrait bust of a Black street kid, (Gamin), was destined to become a career-defining work. Confirmation of her credentials came when she became the first African-American member of the National Association of Women Painters and Sculptors (in 1934). In addition to her sculptures, Savage is widely respected for her pioneering role as an educator, and especially for her efforts in creating arts education programs within her Harlem community.

Accomplishments

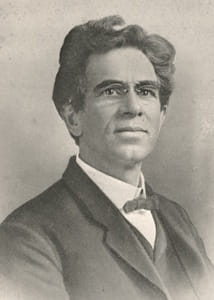

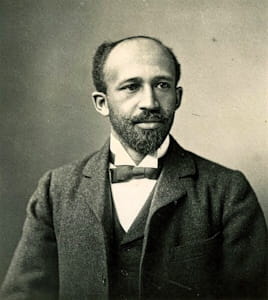

- Savage arrived in Harlem at a time when African American artists, literary figures, scholars, and musicians were working to celebrate and elevate Black culture and experience. As a key presence within the famous Harlem Renaissance, she helped raise the profile of the movement, and of Black female artists, by gaining international recognition for busts of the movement's leading political and cultural figures, including W.E.B. Du Bois, Marcus Garvey, and Dr. William Pickens Sr..

- Savage's realistic renderings of her subjects offered a challenge to the stereotypical ways that African Americans tended to be depicted in art and popular culture. She also helped to expand the roles of Black Americans trying to make their mark on the New York art scene based solely on the merits of their work. On opening the first gallery dedicated to Black American artists, she declared, "we do not ask any special favors as artists because of our race. We only want to represent to you our works and ask you to judge them on their merits. We accept your verdict on this basis and gladly rise or fall on our merit".

- Chief amongst Savage's achievements were her roles in launching the famed Harlem Community Art Center, and by becoming the first African American woman to open and manage a dedicated Black commercial art gallery. She played a vital role as an educator and supporter of some of the finest next generation African American artists, including Jacob Lawrence and Norman Lewis. Curator Tammi Lawson writes, "[Savage] created a pathway for careers for Black artists. She taught them, she gave them the tools, and she got them work".

- Savage placed great value in children, with young boys becoming something of a motif in her art. She humanized working-class African American children in a way that challenged their popular image as rascals and mischief-makers. This worldview, expressed in works such as Gamin (1929) and Boy on a Stump (1940), dovetailed perfectly with her commitment to promoting arts education and appreciation of fine art amongst African American youth.

The Life of Augusta Savage

Curator Jeffreen Hayes states, "I don't think about Augusta Savage as someone who only made objects, [but as someone who] has really left behind a blueprint of what it means to be an artist that centers humanity."

Important Art by Augusta Savage

Gamin

This early bust, and still one of Savage's most well-known pieces, features a young boy dressed in a plain collared shirt and cloth cap. The youth seems in pensive mood as he looks off towards his right; his head cocked ever so slightly. The sitter was in fact Savage's nephews, Ellis Ford. According to the Smithsonian American Art Museum, "[Ford] modeled for this sculpture in 1929 while he and his family were living with [Savage] in Harlem, taking refuge there after losing their home in Florida in a hurricane. Ellis is shown with the soft cap commonly worn by newspaper boys and other working youth. Inscribed on the base is the French word gamin, a term that refers to streetwise children". Savage recalled of sculpting Gamin, "I bought some materials, set a dry goods box on the living room table, stood my nephew alongside the table, and worked practically all night, till we were both exhausted". Given that working with bronze was outside the artist's financial means, Savage finished the original plaster bust with paint and shoe polish to give it a bronze effect.

Curator Jeffreen Hayes writes, "this early work depicts Black youth in a humane way, challenging the visual culture of the period that presented African American children as dirty and ragtag. Gamin was such a successful image, Savage made a number of plaster casts from the original". Indeed, the choice of subject of a working-class child was meaningful for Savage as Ellis came to symbolize her belief that African American of all ages and all socio-economic backgrounds should be able to appreciate, and participate in the production of, art. Gamin helped Savage win the first Rosenwald Fund fellowship ever awarded to a visual artist, and the president of the fund, Edwin Embree, ordered a cast of the work for his personal collection. The African American newspaper, The Chicago Defender, said of Gamin "You like him because you think you know him. You have a feeling that he is the one who threw the baseball into your window pane, who recited such a funny little speech in Sunday school at Easter, and who was wrestling with your own youngster and tore his shirt".

Plaster with paint and shoe polish - Smithsonian American Art Museum, Washington, D.C.

La Citadelle-Freedom

La Citadelle-Freedom depicts a woman looking upward with her left arm raised in a gesture of reverence and/or celebration. Her left foot is also raised and bent behind her as she appears to be balancing on her right toes, almost as if pirouetting in a graceful dance move. A highly symbolic work, curator Jeffreen Hayes, says of the sculpture, "[it] is an instrumental work that demonstrates Savage's adept understanding of sculpture and the medium of bronze. This sculpture represents the freedom African Americans were fighting for during the 1920s and 30s with a nod to the legacy of freedom fighting". In fact, the title of the sculpture tells us that Savage had portrayed a female symbol of freedom inspired by the Haitian revolution where La Citadelle was the name given to the fortress residence of one of Haiti's first rulers of African heritage.

The art historian Theresa Leininger-Miller places La Citadelle-Freedom within a series of "daring sculptures of women" that Savage created during her two-year study period at the Académie de la Grande Chaumière in Paris. Leininger-Miller writes, "In the fall of 1929 Savage went to Paris with funds from both Carnegie and the Julius Rosenwald Fund. There she studied privately with Felix Benneteau and created realistic portrait busts in plaster and clay". She notes that her most notable works of this period were black female nudes such as Amazon and Mourning Victory, and pieces that celebrated her African heritage, such as La Citadelle-Freedom, and Divinité nègre (a figurine with four faces, arms, and legs). In accounting for the figure's expressive pose, Leininger-Miller suggests that "The 'Art of the Dance' published by the American dancer Isadora Duncan might be one of the first inspirations for her work [of this period]. Even artists such as Auguste Rodin and Antoine Bourdelle, whom Savage admired, adored Duncan".

Bronze - Howard University, Washington, D.C.

Bust of Dr. William Pickens Sr.

Some of Savage's most important early works were portrait busts of prominent African-American thinkers and writers such as Pan-Africanist civil rights activist, sociologist, and historian W.E.B. DuBois, and Jamaican-born journalist, entrepreneur, and activist Marcus Garvey. Later, in 1932, she created this bust of African-American activist Dr. William Pickens Sr., who served as Field Secretary, and then Director of Branches, of the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People (NAACP). Pickens was also the author of two influential autobiographies, The Heir of Slaves (1911) and Bursting Bonds (1923). As with her portrait busts of DuBois and Garvey, Savage depicts Pickens thoughtfully, with a calm and dignified expression.

Pickens, Sr., is depicted in a simpler fashion than many of Savage's other busts in that she has not sculpted shoulders or any clothing on the figure. Rather, the viewer is made to focus directly on the head and the face of her sitter. The bust shows Savage's ability to capture the essence of her sitter without the need for unnecessary gestures or embellishments. Curator Jeffreen Hayes states, "this piece reinforces Savage's commitment to activism by celebrating one of the Niagara Movement's key figures and promoting the role of Black artists as creators of Black visual culture". (The Niagara Movement, a cornerstone of the American civil rights movement, was founded in 1905 by Pickens, W. E. B. Du Bois, and William Monroe Trotter. The group used the Niagara Falls as its symbol because it represented the "mighty current" of social change they were striving to achieve.) Hayes adds, that "Completed after Savage's return from Paris, this sculpture exemplifies her attention to depicting authentic portraits of her sitters, thereby challenging dominant images of Blacks in the 1930s". Culture writer Nadja Sayej notes, too, that the influence of Savage's portrait busts of influential African-Americans "can clearly by seen in the work of her student Charles Alston, particularly in his bust of Martin Luther King Jr, which was the first artwork by an African-American to be housed in the White House".

Plaster - Studio Museum Harlem, Harlem, New York

Reclining Nude

As the title describes, this petite sculpture, depicts a nude female whose body is a study in contortion. Her torso twists so her left hand and arm can rest against her slightly bent right leg. Her head is bowed down as if focused intently on the ground below, and her right arm is extended beside her as if to help support her body and keep her semi-upright.

This work is in some ways a departure for Savage in that the depiction of the female form is more modern in her pose than the other, more traditional, ways she has rendered her figures in portrait busts and other sculptures. Of the significance of this work, curator Jeffreen Hayes states, "the reclining nude is a familiar figure in Western art. [...] Savage's Reclining Nude, however, may be the earliest representation of the female body in this trope created by a Black woman, and may be one of the earliest Black female bodies presented in this form. In Savage's depiction, the body is partially exposed - the breasts. This may speak to the modesty expected of women at this time and perhaps to Savage's uneasiness about representing the Black female body with the historical sexualization of Black women".

Marble - Schomburg Center for Research in Black Culture, The New York Public Library, New York City, New York

Gwendolyn Knight

While many of her busts were commissioned works, Savage made others of individuals who she knew and/or admired. This bust is of Gwendolyn Knight, a Barbadian painter and sculptor who studied under Savage at the arts school Savage founded in Harlem in 1934. Knight found a powerful mentor in Savage, once stating "By looking at her, I understood that I could be an artist if I wanted to be". She also encouraged Knight to become more proactive in promoting and exhibiting her work. Savage unveiled her bust of Knight at a February 1935 exhibition of her students' work at the Harlem Y.W.C.A.. The Seattle Art Museum describes how the sculpture "captures Knight's delicate features, penetrating personality, and formidable presence". Author Chelsea Werner-Jatzke adds that Savage's sculpture "exudes the grace and dignity for which the subject was known [and that] Savage's training in classical realism shines through in the portrait".

Savage founded the Harlem Community Art Center out of a desire to make art classes available to regular Harlem residents at little or no cost (depending on the individual's ability to pay). According to curator Jeffreen Hayes, "[Knight] studied under Savage in the 1930s when she returned to Harlem from her studies at Howard University in Washington D.C., after the Great Depression forced her to leave school" and that "the bust is a tender portrait that represented the fondness between student and teacher". It was at the Center that Knight met African-American painter, Jacob Lawrence, whom she married in 1941 (and who, as a couple, dedicated their lives to working to support emerging African-American artists.) Lawrence said of this image (in a 1968 interview) "I think of all of Augusta's work this is surely one of the most resolved pieces plastically".

Painted plaster - Seattle Art Museum, Seattle, Washington

Lift Every Voice and Sing (The Harp)

Savage was commissioned to make a sculpture symbolizing African-American music for the 1939 World's Fair in New York. Her sculpture, which was an imposing sixteen-feet-tall, took the form of a harp, but with twelve upright African-American figures, their mouths open in song, in the place of strings, and with the vertical folds of their choir robes mimicking the form of the strings. A hand outstretched from the base at a forty-five-degree angle cradles the figures (in place of a harp's wooden soundboard). The hand was meant to represent "the hand of God". At the front of the sculpture, replacing the foot pedestal, one more male African-American figure crouches down and holds sheet music. Savage drew inspiration for the work from the 1900 poem, "Lift Every Voice and Sing", had been written by her friend and civil rights activist James Weldon Johnson (he had passed away the previous year) and was then set to music and made into a hymn by his brother John Rosamond Johnson in 1905. The song/hymn came to be known as the "Negro national anthem".

According to curator Tammi Lawson (and having long since established a name for herself within Harlem's artistic circles) The Harp brought Savage to a larger, more diverse, American audience. She explains how The Harp "was placed in the courtyard of the Contemporary Arts Pavilion at the World's Fair and was seen by millions of visitors. Maquettes of the crowd-pleasing work were made and sold as very popular souvenirs of the fair". Despite its high profile, it was displayed alongside works by the likes of Waylande Gregory and Salvador Dalí (and an un-and-coming Willem de Kooning), Savage did not have sufficient funds to cast the work in bronze, or to transport and store the plaster version, and it was destroyed, smashed by bulldozers at the closing of the fair in 1940. Today (photos of the original sculpture such as this notwithstanding), the memory of the original work is preserved in bronze casts of significantly reduced size.

Culture writer Concepción de León writes that "The story of the commission and destruction of 'The Harp' and its eventual fate is a microcosm of the challenges Savage faced - and the ones Black artists dealt with at the time and are still dealing with today". Plans are in place for a replica of Savage's statue to be installed in the Lift Ev'ry Voice and Sing Park, currently under construction in the historic LaVilla neighborhood in Jacksonville, Florida where it will honor the memory of the Johnson brothers, two of Jacksonville's most famous residents.

Plaster - Destroyed

The Pugilist

The Pugilist (the name given to a professional boxer) is a bronze sculpture of Jack Johnson. He became the world's first Black heavyweight boxing champion after defeating Canadian Tommy Burns in 1908. Nicknamed the "Galveston Giant", his 1910 bout against the white American boxer, James J. Jeffries, was dubbed the "fight of the century" and his defeat of Jeffries sparked a spate of race riots across the country. In the work, Johnson is shown from the waist-up. His arms are crossed proudly across his muscular chest. The muscles of his arms, neck, and abdomen, are also well-defined. His expression is stoic and strong, gazing out defiantly. Speaking of her work of this period, Curator Jeffreen Hayes has commented on Savage's "mastery of the human figure [which was] very attuned to the visual culture of the period and to the 'New Negro' mandate to advance racial pride through the arts".

Curator Wendy N. E. Ikemoto says of the The Pugilist, "It's a tiny sculpture but has enormous presence. It captures her own fighting spirit in fighting alongside him against racial oppression". Similarly, black studies professor, journalist, and activist Herb Boyd recognizes this work as evidence that Savage "still possessed the vision and energy to create valuable art", despite the ongoing financial hardships she faced. On that note, the historian Gillian Wolf writes, "A late work by an artist renowned for her portrayal of personality and character, 'The Pugilist' expresses most clearly the way [Savage's] life shaped her personality. Intent upon showing physical suppleness and humor she often produced works that over-portentous critics labeled 'trivial.' [...] In the end her struggles on behalf of others exhausted her, and she simply waited, like 'The Pugilist,' to deal with life's next challenge". It was one of her last works, produced before retreating from New York, and the New York artworld, to a new life in the Catskill Mountains.

Bronze - The Schomburg Center for Research in Black Culture, New York, New York

Biography of Augusta Savage

Childhood and Education

The seventh of fourteen children, Augusta Christine Fells was the daughter of Cornelia and Edward Fells. Both had been slaves before the ratification of the Thirteenth Amendment in 1865 (which finally abolished slavery in the United States), after which, Edward found work as both a carpenter and a fisherman. But it was his role as a preacher with the African Methodist Episcopal Church that would have the most direct impact on Augusta's formative years. According to curator and author Tammi Lawson, "Augusta was a precocious child who quickly advanced from making mud pies to shaping clay figurines of animals she saw around her". However, Edward held particularly strong views about the Bible's condemnation of "graven images" in the Ten Commandments and was thus angered when Augusta engaged in the "sinful" act of modeling from red clay. As she later recalled, "My father licked [beat] me four or five times a week, and almost whipped all the art out of me".

At fifteen years old Augusta dropped out of high school (and escaped her oppressive homelife) and married John T. Moore. She gave birth to a daughter, Irene Connie Moore, but sadly John died shortly after her birth, forcing a seventeen-year-old Savage to return to her parents' home. With them, Augusta moved to West Palm Beach, Florida, where she resumed her high school education. Historian Gillian Wolf writes, "Withering in the face of her father's disapproval and the scarcity of clay in the area, [her art making] came to a stop, until she chanced upon the Chase Potteries on the outskirts of town. Augusta begged a pailful of clay from the owner and modeled a little statue of the Virgin Mary for her over-strict father. This not only impressed him into allowing her to continue her art undisturbed, but also persuaded the school board to appoint her to teach modeling during her senior year, at a 'salary' of one dollar per day".

Early Training

After high school, Augusta briefly attended two colleges: the Florida Agricultural and Mechanical University for Negroes (FAMU) (now Florida A&M University), and Tallahassee State University. Her academic career did not last long however and in 1915 she married a carpenter named James Savage. While they divorced after just a few months, Augusta kept his last name for the rest of her professional life.

Savage's first taste of professional recognition came in 1919 when she exhibited sculptures at the West Palm Beach County Fair. She sold some of her pieces and also won a $25 cash prize. Her win brought her to the attention of George Graham Currie, the Fair's superintendent, who was so impressed with her work that he commissioned her to sculpt his bust. Savage moved briefly to Jacksonville, Florida, where she hoped to make a living sculpting busts of professional African Americans. Her venture failed to take off, however, and, at Currie's urging, in 1921 she left her daughter in the care of her parents and relocated to New York City in the hope of realizing her ambition of becoming a successful sculptor.

Mature Period

Once in New York Savage hoped to attend the School of American Sculpture, founded by the sculptor Solon Borglum. Savage was penniless and unable to afford the tuition fees. However, Borglum wrote her a letter of recommendation for a scholarship at the Cooper Union for the Advancement of Science and Art. Wolf writes, "This small effort on Borglum's part opened the gateway to her artistic future. His recommendation, as well as the bust of a Harlem minister that she modeled overnight, sent her to the top of a 142-strong waiting list for Cooper Union, then won her immediate entry for a four-year course of study [commenced in October 1921]". One of her most influential teachers at Cooper Union was the American sculptor George Brewster, who was well known for his portrait busts and historical monuments.

During this time, Savage was working as an apartment caretaker and laundry assistant, but when her hours were reduced, Cooper granted her further funds to help with her day-to-day living expenses. Savage spent her downtime learning about African art and culture. The New York Public Library writes, "[Savage frequented] the 135th Street Branch Library located in Harlem, known today as The Schomburg Center for Research in Black Culture, attending lectures and participating in poetry readings. Her talent as a sculptor [was] immediately recognized, and the library commission[ed] her to sculpt a portrait bust of W.E.B. DuBois ([the sculpture's]whereabouts unknown). She [began] to sculpt several notable portraits of leading Harlemites growing her reputation and her skills while earning money. Savage publish[ed] her poetry in Negro World, a newspaper founded by Marcus Garvey, and [sculpted] a portrait bust of him".

Savage was thrilled when, in 1923, she was one of 100 women who won a scholarship to study at France's prestigious Fontainebleau School of Fine Arts. As curator Jeffreen Hayes explains, "Although the French government sponsored the program, an American selection committee comprised entirely of White men - the American Committee of Eminent American Architects, Painters, and Sculptors - identified the awardees. Unbeknownst to them, they had selected a Black woman; once they learned that Savage was Black, her scholarship was rescinded on the basis that Southern White women should not be expected to share travel accommodations with a Black woman". Lawson writes, "devastated but determined, [Savage] took her case to the public with an intense letter-writing campaign to shed light on her situation and to advocate for fair and unbiased treatment for future Black applicants. Her case was covered in both Black and white newspapers across the country. The one dissenting member of the committee Hermon MacNeil, president of the National Sculpture Society, invited her to study privately with him in his studio in Long Island, New York".

Writing on Savage's behalf, Du Bois wrote letters to each of the committee members admonishing them for their bigotry. Indeed, the incident saw Savage herself assume the role of activist which she confirmed in a letter in May 1923 to the editor of the New York World: "I hear so many complaints to the effect that Negroes do not take advantage of the educational opportunities offered them ... For how am I to compete with other American artists if I am not to be given the same opportunity? I don't so much care for myself because I will get along all right here [in New York], but other and better colored students might wish to apply sometime. This is the first year the school is open and I am the first colored girl to apply. I don't like to see them establish a precedent".

During this period, Savage also had to deal with serious familial difficulties. Her father suffered a debilitating stroke around the same time a hurricane made her parents' home uninhabitable. Savage was left with no choice but to take in her family (including her daughter) into her home in New York. Lawson states, "At one point, there were nine people living in Augusta's one-bedroom apartment. Her father and one of her brothers died in the space of a year". This difficult situation impacted directly on Savage's art career too. Du Bois had recommended her for a scholarship to study in Rome, but she needed the money she had saved for the trip to support her family.

Adding to Savage's woes were the attentions of a mentally unstable (diagnosed psychopathic) man, named Joe Gould, who became obsessed with Savage after meeting her at a poetry reading in 1923. He stalked her, harassed her through letters and phone calls (in which he repeatedly proposed marriage). And although never confirmed by the artist, it is believed by some that Gould, who had carried out violent attacks on other women, possibly even raped her. Savage would endure Gould's harassment on-and-off (he was repeatedly held in psychiatric institutions) for about two decades.

Savage, who was by now heavily involved with the Universal Negro Improvement Association (UNIA), met and fell in love with the journalist, and UNIA's Secretary General, Robert L. Poston, who she married in December 1923. Just a few months after their marriage, Poston was sent to Africa by the UNIA to finalize arrangements for a planned mass emigration of African Americans to Liberia. Tragically, on the return journey in March 1924, he passed away due to lobar pneumonia. A pregnant Savage was so distraught she went into premature labor and her second daughter, Roberta, died after just a few days. Savage (who never remarried) still managed to complete her studies at Cooper Union in 1924, a year ahead of schedule.

After graduating (with a degree in fine art), Savage joined the creative community of African American artists and writers gathered in Harlem. As academic Dr. Howard Dodson writes, "the Harlem Renaissance or, as it was called at the time, the New Negro Movement [...] was an explosive period of African American artistic and cultural creativity that marked a new stage of Black consciousness and development.". In 1928, Savage participated in an exhibition at the Harmon Foundation, where her Head of a Negro won the Otto Kahn Prize. However, she openly criticized Mary Beattle Brady, the director of the Foundation, as well as many of the Foundation's white patrons, for their fetishization of the "negro primitive" aesthetic.

At the same time, Savage began exhibiting her sculptures throughout New York to rave reviews. In September 1929, A photograph of her bust of her nephew Ellis Ford, Gamin (1929), featured on the cover of Opportunity, a literary magazine dedicated to Black culture. The magazine was closely associated with members of the Harlem Renaissance. On seeing the cover image, the Julius Rosenwald Fund offered Savage a scholarship to study in Paris and the following year she finally arrived in Europe. In Paris, she lived in an apartment in Montparnasse, studied at the Académie de la Grande Chaumière (an institution already associated with Harlem Renaissance writers such as Claude McKay and Countee Cullen) and worked in the studio of one of her professors, the French sculptor Felix Benneteau-Desgrois. She also studied under sculptor Charles Despiau. However, Savage later rued that her teachers in Paris were "not in sympathy [with me] as they all have their own definite ideas and usually wish their pupils to follow their particular method".

Despite these misgivings, Savage earned a name for herself through the presentation of her works in various exhibitions and salons. As the art historian Theresa Leininger-Miller writes, "In 1930 La dépêche africaine, a French journal, ran a cover story on Savage, and three of her figurative works were exhibited at the Salon d'Automne. Savage also sent works to the United States for display; the Harmon Foundation exhibited Gamin in 1930 and Bust and The Chase (in palm wood) in 1931. In 1931 Savage won a gold medal for a piece at the Colonial Exposition and exhibited two female nudes (Nu in bronze, and Martiniquaise in plaster) at the Société des Artistes Français". In 1931, she successfully applied for a second Rosenwald scholarship, and received a Carnegie Foundation grant, that allowed her to remain in Europe for an additional year. She found time to traveling more widely throughout France, and toured Belgium and Germany where she visited many cathedrals and museums.

Later Period

![Of her role as his teacher, painter Jacob Lewis (pictured) stated: “[Savage] was very influential in making me a professional. [...] She believed in people. Not just me, but many, many of the artists around”.](/images20/photo/photo_savage_augusta_4.jpg)

Savage returned Harlem in 1932, her reputation now in its ascendency. She earned the distinction of being the first African American member elected to the National Association of Women Painters and Sculptors in 1934. Despite this being the period of the Great Depression, Savage's bust commissions were still in high demand. However, given that she was still having to support her large family, money remained tight. To supplement the income from her commissions, Savage took on the role of art teacher at the Harlem library, and later opened a studio, the Savage Studio of Arts and Crafts, in a basement on West 143rd Street. At the studio, African-American students could attend painting, drawing, and sculpting classes. Curator Wendy N. E. Ikemoto notes that, even though Savage was in a difficult financial position herself, if her students "didn't have money to buy their own art supplies, she let them use hers". Attendees of the Studio included future prominent Black artists: Jacob Lawrence, Norman Lewis, and Gwendolyn Knight.

Like many artists of the period, Savage was a beneficiary of Franklin D. Roosevelt's Works Progress Administration (WPA) program, establishing the Harlem Artists Guild (with multidisciplinary artist Charles Alston, and muralist Elba Lightfoot), and the Harlem Art Workshop, in 1935. As Lawson explains, "With money from the WPA, she was able to expand and offer classes in painting, drawing, costume design, composition, sculpture, ceramics, metalcraft, weaving, rug making, lithography, block printing, and photography. [...] Conveying to her students the art techniques she had learned while studying in Europe, Augusta encouraged them to create artwork reflective of Harlem culture and African American identity". Such was her success with these initiatives, Savage won further WPA funding which she used to open the Harlem Community Art Center. Lawson states, "providing instruction to 1,500 students and employing a cadre of artists, the center, recognized for excellence, became the model for WPA-sponsored art schools across the nation and drew influential visitors such as First Lady Eleanor Roosevelt".

Savage's reputation as both artist and teacher led to what was perhaps her greatest commission in 1937. She was tasked with designing one of the thirty-five sculptures for the 1939 World's Fair in Queens, New York. Her sculpture, known as, The Harp, which featured a sixteen-foot-tall harp made out of African-American figures, became one of the most visited works at the Fair. Despite the work's positive public and critical reception, Savage lacked the funds to have it stored after the fair, or to have it cast in bronze, and the sculpture was destroyed. According to writer Concepción de León, "the story of the commission and destruction of 'The Harp' and its eventual fate is a microcosm of the challenges Savage faced [...]. Savage was an important artist held back not by talent but by financial limitations and sociocultural barriers" (this issue might help account for why, today, most of her works exist only in plaster).

Following her success at the World's Fair, Savage opened the Salon of Contemporary Negro Art, making her the first African-American woman to open her own gallery. Artists who exhibited there included Beauford Delaney, James Lesesne Wells, Lois Mailou Jones, and Richmond Barthe. At the inaugural exhibition, some 500 people were in attendance, and Savage announced "We do not ask any special favors as artists because of our race. We only want to present to you our works and ask you to judge them on their merits." Although the exhibitions were well-attended, and well-received by critics, sales were few, and the Salon closed within a few months.

Sadly, the slow decline of Savage's career seemed to coincide with the failure of the Salon. Lawson writes, "there are many speculations as to why Augusta Savage's career seemingly ended. One possible factor may have been the discouragement of feeling 'passed over,' as the art world moved away from her classic style and increasingly toward abstraction. Some of her work was lost in transit to a gallery show in another state. [...] There was the onset of World War II. Augusta was almost fifty, still piecing together a living. It is not hard to imagine that she must have felt defeated".

By 1945, Savage's financial situation had not improved, and she became severely depressed. She moved to a farmhouse in Saugerties in the Catskill Mountains where she established close friendships with her neighbors, raised pigeons and chickens (which she sold, along with their eggs), and received friends and family members who would visit from the city. She also took a job at the K-B Products Corporation as a laboratory assistant in the cancer research facility. She managed to purchase a car and learned to drive. The laboratory director, Herman K. Knaust, purchased art supplies for Savage, and encouraged her not to stop creating. Savage continued to produce her own work in a converted garden studio, and taught sculpting to children at summer camps. She also produced portrait busts for tourists and experimented with writing children's books and murder mysteries (though none were ever published). (In 2001, Savage's home and studio in Saugerties were placed on the New York State and National Register of Historic Places.) When she was diagnosed with terminal cancer she returned to New York City to live with her daughter Irene, with whom she had recently reconnected. Savage passed away in March of 1962.

The Legacy of Augusta Savage

Augusta Savage's sculptures, and, indeed, her role as a female sculptor, helped to promote an image of African Americans that challenged entrenched ideas about race and sex in the first half of the twentieth century. She demonstrated, through her prominent position with the Harlem Renaissance movement, how an artist could act as an engine for social activism and change and, how they might create art that helped dismantle hierarchies in the contemporary New York art world. Curator Wendy N.E. Ikemoto asserts that Savage's "inventive, gorgeous" sculptures communicated her mission "to promote Black arts and the Black community", while library director Dr. Howard Dodson, states that, "the roles she played in the development of art and artists in Harlem solidly establishes Augusta Savage [as an] artist, whose life, work, and legacy have had a broad and enduring impact on African American and American art".

Savage's bequest is equally as a sculptor and as an arts educator. As curator Jeffreen Hayes states, "Savage built her legacy through the many young people and adults she taught and to whom she provided studio space among them William Artis, Ernest Crichlow, Gwendolyn Knight, Jacob Lawrence, Norman Lewis, and even Morgan and Marvin Smith". Commenting specifically on her role as director of the Harlem Community Art Center, Hayes adds, "though her tenure [...] was short, Savage's tenacity for educating the community through art was far-reaching, shaping the space and serving as a foundation for [...] art centers around the country". Despite the many honors accolades for her art, Savage, reflecting on her role as a teacher, said, "I have created nothing really beautiful, really lasting, but if I can inspire one of these youngsters to develop the talent I know they possess, then my monument will be in their work".

Influences and Connections

-

![Norman Lewis]() Norman Lewis

Norman Lewis ![Charles Alston]() Charles Alston

Charles Alston- Hermon Atkins MacNeil

- Felix Benneteau-Desgrois

- Charles Despiau

-

![Henry Ossawa Tanner]() Henry Ossawa Tanner

Henry Ossawa Tanner - George Currie

- W.E.B. Du Bois

- Herman Knaust

- Kate L. Reynolds

-

![Jacob Lawrence]() Jacob Lawrence

Jacob Lawrence -

![Norman Lewis]() Norman Lewis

Norman Lewis - Gwendolyn Knight

- Marvin Smith

- Morgan Smith

-

![Henry Ossawa Tanner]() Henry Ossawa Tanner

Henry Ossawa Tanner - George Currie

- W.E.B. Du Bois

- Herman Knaust

- Kate L. Reynolds

Useful Resources on Augusta Savage

- Augusta Savage: hidden artistBy C. Washing

- Augusta Savage: The Shape of a Sculptor's LifeOur PickBy Marilyn Nelson

Ask The Art Story AI

Ask The Art Story AI