Summary of Sean Scully

Scully came to international prominence as a painter of abstract works featuring combinations of squares and stripes. Having abandoned figurativism in the mid-1960s, and a series of precise line paintings in the early 1970s, he turned to "sculptural" canvases that got their name because they featured heavy, tangible, stretches of paint and abutted panels that impose themselves on the viewer. These signature works left behind the almost technical precision of his line compositions in favor of a freer application of paint that gave rise to an expressive translation of color, light, and texture. Scully's paintings appear to have no referent but thematically they often deal with metaphorical ideas that touch on the artist's own spirituality and memories of people, places and objects. In more recent years Scully has focused more on sculpture, working with Corten and stainless steel to produce imposing, stripped back, monuments that celebrate, rather than disguise, their grid-like structure.

Accomplishments

- Inspired initially by the optical effects of Bridget Riley's stripped patterns, Scully's early 1970s works presented a series of supergrid paintings featuring tight overlapping and precise linear patterns that revelled in their "musical" combination of color and light. The idea of marrying symmetry with expression went a long way to revive the fortunes of abstraction after a decade in which Pop Art had dominated.

- Once Scully had encountered Conceptual Art and Minimalism, he moved on from his aesthetic grid paintings to a more stripped-back style. He describes taking his work back to "ground zero" by which he meant a focus on the perfectly rendered stripe. The result was a unique series of works that aimed to use the stripe to stimulate in the viewer a pure spiritual experience. Even though Scully referred to the works as romantic and quasi-religious, his line paintings were very highly prized amongst the elite New York Minimalists who saw him as one of their own.

- Following a personal tragedy, Scully abandoned his meticulous line paintings for a style that featured a series of colored blocks and panels, applied through the thick application of paint. These melancholic works related more to the physical world and alluding (albeit obliquely) to the challenges and frailties of human relationships. Nick Orchard, Head of Modern British Art at Christie's, suggested that these works "create [a sombre] mood in a way that no other painter has since Rothko".

- Scully's larger scale canvases, such as those featured in his Landline series, evoke in the viewer the idea of the sublime. The concept of the sublime is used to explain a picture quality that generates such physical, moral, aesthetic and/or spiritual intensity the viewer's ability to comprehend the work is temporarily overwhelmed. This series, produced during a period of debilitating physical suffering, carry within their fluid lines an intense emotional experience.

- Scully is associated with the concept of "floating paintings" which feature hand painted (imperfect) vertical stripes. Attached to the gallery wall by one edge, these works assume a middle ground somewhere between sculpture and painting. Refuting the idea that these pieces might be considered pure sculptures, Scully likened them rather to architectural illusions in that they asked the viewer to consider both the painting and the space that surrounded it. Indeed, these non-traditional, site-specific, "sculptures" saw the artist associated with the rise of Post-Minimalism.

Important Art by Sean Scully

Shadow

A series of precise, horizontal bands run across the surface of this painting, while in the background vertical black strips and wavering colors appear to be moving. The combination of distortion and focus creates depth and movement, as if we are viewing something rushing past us through a slatted screen.

Scully made this painting while he was still a student at Newcastle University. He was drawn to the visual effects of Op Art, particularly the "low optical hum" and all-over striped patterns in Bridget Riley's heat haze paintings. He called his paintings his "supergrids" since they were tightly woven networks charged with electrical energy and momentum. Precise lines were made using masking tape as a ruler, producing a razor-sharp edge.

The industrial landscape of Newcastle filtered through into these paintings, particularly the layered, moving views seen from the train ride in and out of the city. As Scully explained, "When I made these paintings I was living in Newcastle, which is a shipbuilding town dissected by a river. The river is crossed by nine bridges made of overlapping steel girders, and as you look out you see overlapping grids as you go across". The "supergrids" can also be read more generally as reflections on urban living, combining structure, energy and movement into a dizzying, frenetic display of color and light. Scully likened these paintings to music producer Phil Spector's idea of a "wall of sound", where layers are built on top of one another to create a deep, rich complexity. The relationships between order, expression and layering here are ongoing concerns in Scully's practice, which he continues to explore in his artworks to this day.

Acrylic on canvas - Private Collection

Diptych

The canvas here is divided into two halves, each with a tightly woven series of white and grey bands running horizontally across the surface, like light filtering through a blind. Colors are soft and muted; when seen so close together they create the effect of quiet vibrations or movement. There are little to no traces of brushwork here, thereby facilitating an aura of purity and calm.

This painting typifies the work Scully was producing in the mid-1970s having received a Harkness Fellowship to study in New York for two years. While in the city he encountered Conceptualism and Minimalism. He duly abandoned his grid paintings in favour of meticulously painted stripes in the spirit of Ad Reinhardt, Agnes Martin, Frank Stella and Francois Morellet. Scully stripped his paintings back to basics, saying "I took out of my work all triviality or everything that could possibly be described as decorative or ornamental [...] I got rid of everything in my work except the one thing that was just before ground zero, and that was a stripe".

Scully aimed to lift his paintings onto a higher intellectual plane by filling them with a poetic, spiritual energy beyond the realms of the real world and making them akin to religious icons: "I was searching for some form of deep pathos, a form of poetic expression that went somehow below the surface of appearances [...] on a rigorous quest for some kind of deep, pure, religious, or quasi-religious meaning". Much like Piet Mondrian, he invested significant meaning in the structure of the work, with the diptych format referencing religious iconography, while his horizontal and vertical bands were loaded with symbolism. As he explained, "The horizon embodies the permanent, the eternal, while the vertical stands for our human position". Although Scully insisted such paintings were predominantly romantic and religious, they brought him considerable recognition as a New York Minimalist.

Acrylic and tape on canvas

Paul

Paul is a triptych made from three painted panels joined together with each containing its own stripe pattern. Two larger, muted panels sit at the back, while on top a bold black and white strip draws the eye in, creating a strong focal point. Scully invites us to consider the intimate relationships between the panels, while also reading them together as a whole.

By 1984 Scully had abandoned the masking tape precision of his earlier paintings, searching instead for a style which connected back to the real world. The paintings that came out of this period, including Paul, were earthy and battered looking, with bold slabs and stripes of brooding, intensely worked areas of color, containing what art critic Arthur C Danto called, "walls of light". Unlike his earlier grid paintings, horizontal and vertical lines do not intersect, instead they sit side-by-side creating an almost solid form sculpted from paint. Danto wrote, "what one cannot help but be attracted to, in front of one of these surfaces, is the way the paint is laid on [it] makes us conscious of the brushes made up of bristles, which leave traces of their physical interaction with the viscosity of paint".

This painting is dedicated to the artist's son, Paul, who died in a car crash a year before the work was made. Through his grief Scully continued to paint, but emotions spilled over into his paintings, which took on deeply melancholic colors, As he explained, "From 1983, you can see that someone came in and kind of [...] dimmed the lights in my paintings. They went dark and they stayed that way for a long time".

The spiritual, symbolic quality of Scully's earlier Minimalist paintings continues to play an important role here, with the triptych format referencing religious iconography. The intimacy of human relationships are often explored in Scully's paintings through the interaction of colored blocks and panels; there is a suggestion of the family trio of father, mother and son here, with Paul placed at the centre. With bright white paint brushed over black, the panel seems to emit light from darkness, suggesting hope through the eternal.

Oil on linen - Collection of the Tate, United Kingdom

Catherine

This work is one of Scully's Plaid Series, exploring checkerboard pattern onto which inset blocks of color are placed. A black and red checkerboard is offset with two striped rectangular panels, resembling flag patterns. The dark, richly colored background recalls contrasts with the vibrant panels on top, which appear to float on the surface, while the iridescent white stripes seem to reflect light outwards like a mirror.

This painting is dedicated to the artist Catherine Lee, Sean Scully's second wife. Between 1979 and 1996 Scully and Lee would select his best painting from the year and add it to the Catherine Series, which is now on permanent display at the Modern Art Museum of Fort Worth. Scully spoke highly of Lee: "That relationship has [...] made a lot of things possible for both of us [...] we came here to New York and we really did help each other enormously". The series as a whole features variations on Scully's distinctive stripe patterns, revealing the difference and repetition in his paintings as they evolved over nearly two decades. Art historian Brian Kennedy says the series is, "absolutely and intrinsically connected to real time".

Scully and Lee were living in New York while making the Catherine Series and the city's patchwork architecture had an influence on the structure of his work. But at a deeper level, his paintings, especially those in this series, contained what art historian David Carrier calls "the ghost of figuration", with oblique, symbolic references to figures and relationships that he had within the city. Scully put it thus: "Those people who are friends of mine are affecting, infecting my work. That's how my work is made, through the vitality of these relations". Such relationships can be read in Scully's paintings through the ways emotive colors bump up against or sit on top of one another, suggesting the complexities and challenges of being together and apart from the people we love.

Oil on linen - Modern Art Museum of Fort Worth, TX

Floating Painting #5

Scully's Floating Painting projects outwards into the gallery, attached to the wall by one side. In occupying real space the work hovers somewhere between painting and sculpture, straddling a middle ground in between. The whole surface is painted with Scully's distinctive black and white, vertical stripes.

This work is one of a series of Floating Paintings Scully made in the 1990s, which always contained hand painted vertical stripes. Their geometric language resembles Donald Judd's wall mounted sculptures or the artist's former wife, sculptor Catherine Lee's painted objects. But Scully defined them as paintings, saying, "These painted metal boxes occupy space, but at the same time they vanish, they disappear. I think that's why you call them floating paintings. They can't hold themselves as sculptural objects". The painted stripes cover the entire work on all three visible sides, which sticks out into space, in Scully's words, "like a shark fin in water".

Unlike the work of many of his Minimalist contemporaries, however, Scully's Floating Paintings have an inherent fragility. Suspended by only one edge to the wall, the painting's broad, expressive stripes are human and imperfect, with rough visible brushstrokes giving them a humble quality, eliciting an emotional response from the viewer. As Scully explains, "the important point about the painted box, is that it's painted with very energetic brushstrokes that follow yet somehow emotionalise this shape that is precariously attached to the wall".

Scully is intrigued by the secret space hidden within the box, aiding a further sense of mystery and intrigue. He also considers the space around the box and the ways the painted vertical stripes can create the illusion of architectural form or bands of light on its surface. These painted metal objects preceded Scully's more recent interest in sculpture and painting on aluminium panels, which continue his interest in the possibilities for investing human emotion and allegorical content into geometric abstraction, in both two and three dimensions.

Oil on metal

Landline Skyline

A series of horizontal bands spread across the surface of this painting, bleeding into and overlapping one another. The muted tones of blues, greys and blacks are quiet and unassuming, while thickly applied passages of paint spread across the surface suggesting movement.

This work is one of Scully's most recent paintings, part of the ongoing Landline Series which he began in 2013. In contrast with many of his previous paintings, which explore the conflict between horizontal and vertical stripes, the verticals have been removed here. Scully explained, "I took out the vertical, which was my column and my architecture, and what I was left with was the horizon. And so I could begin my journey along it". The horizontal bands make reference to the infinite nature of the landscape, suggesting the points where land, sea and sky meet and rub up against one another. Scully has likened many of the paintings in the series to the city of Venice, where lapping water ripples against careworn buildings and reflects fractured ripples from the sun. The light captured in these paintings differs from previous paintings, which have tended towards rich, earthy tones and a romantic melancholia; here the cool colors suggest a white, bright Mediterranean light.

The Landline Series followed a period of significant ill health during which Scully suffered a series of debilitating back problems which he took some time to recover from. On his recovery he channelled this difficult, emotional experience into these new paintings, which hold hidden depths of intense pain beneath their seemingly tranquil surface. Art historian Kelly Grovier writes, "The landline series [...] is a poignant record of this intense trauma [...] The simplicity of the formal arrangements and their refrain of restricted hues belie a complexity of physical and emotional anguish conducting through each wired bar like a muffled scream of twisted electricity".

Scully made this painting on a smooth aluminium surface, which gives the paint a looser, more aqueous quality suggesting the undulating movement of water across an endless horizon. As with all his previous work the paint is built up in a complex series of layers, with elements of underpainting just visible through small channels and rivers, reflecting the complexity of emotional experience embedded into the artwork.

Oil on aluminium - Private Collection

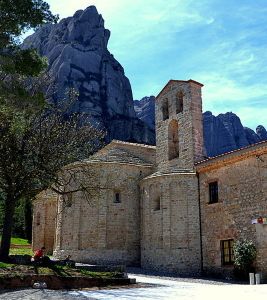

Church of Santa Cecília de Montserrat

The Santa Cecilia project was conceived of following a chance meeting between Scully (who has a studio in the Barcelona) and Father Josep M. Soler, director of the museum of Montserrat. The thousand-year-old Santa Cecilia de Montserrat chapel, which sits in the hills overlooking the Catalan capital, was restored in 2015 with Scully's permanent 22 piece installation representing the culmination of a ten year project. The installation, which Scully described as the most "significant and important" work of his career, featured abstract painting, frescoes, stained glass windows and even metal-cast candlesticks. Scully painted onto metal and steel with the goal of making works that would, in his words, "still be here in [another] thousand years".

On entering the chapel, worshippers are greeted with a vast gray and black Doric painting while a fresco made up of abstract squares of black, brown, and yellow sits beneath a yellow stained glass window. The outer wing on the chapel houses a 14-piece panel set in steel, and though these make only oblique reference to the 14 stations of the cross, the chapel does feature three glass-cut crosses: two hanging on the wall and the other adorning the altar. At the very heart of the chapel hangs the painting Cecilia, which includes two insets that allude to a musical score. The painting is in fact dedicated to the memory of Scully's mother (Ivy). He said of the painting, "Cecilia is the patron saint of music and my mother was a singer [...] When we were little kids we would go to the Vaudeville and my mother would sing Unchained Melody and she would always bring the house down. So I was very struck by that musical connection when I was choosing works".

Barcelona, Spain

Boxes of Air

This monumental sculpture is constructed from a series of empty boxes in various sizes stacked on top of one another. They resemble scaffolding, an oil rig or perhaps the bare bones of a construction site. Scully produced this 15 metre long sculpture in Cor-Ten steel, selected for its ability to weather and rust naturally, and thereby producing the same rugged, care-worn effects of his hard-won paintings. Existing as empty, three-dimensional frames, they are intended to contain blocks of light, air and color from their surrounding space. Scully has made several version of this same sculpture but given its site specific nature it takes on distinct characteristics depending on its environment.

As with his best-known paintings, Scully's more recent sculptures continue to explore the narrow framework of geometry and abstraction. The complex arrangement of interwoven lines resemble his supergrid paintings from the 1970s, while the boxes of "air" inside can be likened to the blocks in his paintings, which he has described as "soft packets of wrapped air that I put into place". Scully was particularly influenced by contemporary Japanese architecture when designing this sculpture and cites Tadao Ando's Church of Light in Japan and his Museum of Modern Art in Fort Worth (with its floating pavilions) and Arato Isozaki's Himalayas Museum in Shanghai.

Yet Scully's sculpture can be seen as an extension of his grid paintings (only here exposed to the shifting and changing position of the viewer and the changing quality of natural light). Boxes of Air works somewhat circuitously as a link back to Scully's deprived childhood when he recalls having been made to darn socks for his whole family. But it proved that the weft and weave of this humbling activity set the foundations for the grid-like paintings and sculptures of one of the most important international abstract painters working today.

Cor-Ten Steel, Edition 1 of 3 - Château La Coste, Le Puy-Sainte-Réparade, France

Biography of Sean Scully

Childhood

The eldest of two boys, Sean Scully was born in Dublin, Ireland in 1945. When he was just four years old, his family emigrated to London, travelling by boat across the Irish Sea in search of a new life (Scully later dedicated his painting Precious (1985) to this perilous journey during which the boat was lost at sea for over eight hours). Once in London, the Scully family settled in an Irish community in Islington, before moving to the suburbs of Sydenham. Though he considered himself an adopted son of London, Scully was proud of his Irish heritage stating "I'm Irish in the mythic, romantic sense but, in the living sense, I'm a Londoner".

Scully remembers his childhood as an unsettled time, marred by poverty, anger and domestic violence. He described his mother as a strong, forceful character who was overprotective of her eldest son. Scully said, "I had a desperately unhappy childhood because in our house two people were always in a state of not being loved - usually my brother Tony and my dad". As an escape from his tumultuous family life Scully developed a penchant for saving and caring for injured birds.

The Scully family regularly attended Catholic Church and Sean recalled how the church offered a place of spiritual refuge from the grim realities of school life: "(church) was all reds and golds and whites and black, then I went to the local school and I entered a world that was grey, hard, spiritually empty and very, very violent". Indeed, the first paintings Scully encountered were during Catholic mass. He specifically recalls seeing a series of devotional paintings ("They were very geometric, like Russian paintings" he later recalled) known as the stations of the cross, illustrating the scenes leading to Christ's crucifixion. He also came across a reproduction of Picasso's 1901 painting Child with a Dove, stating that "it was as important to me as the Church in pointing to art as an escape from that working class environment". By the tender age of 9, Scully had already decided he would become an artist.

Scully left school at the age of 15 and took on many different jobs to support himself including working as a messenger, a trainee photograph re-toucher, a letterpress typographer, a plasterer and a crane operator. During this unsettled period he became a member of a street gang, later admitting, "I was brawling, committing burglary, gang-fighting. It was rough, seriously rough". But despite his adolescent transgressions, Scully always carried the Catholic conviction that life always offered a better situation and he was soon using his spare time more creatively.

Early Training and Work

After turning 17, Scully began to attend night school, gaining qualifications through the help of an educational programme called Floodlight. He also began to attend evening classes at the Central School of Art in London, developing a particular interest in figurative painting. When he was 19, Scully saw Vincent van Gogh's Chair (1888) at the Tate Gallery in London. It proved to be a moment of epiphany: "Until then, all paintings, including the ones I liked, seemed to be about artifice [...] the Chair, looked so honest, like anybody could have painted it. That had a profound effect on me. Looking at that painting was like looking through a beautiful window. It gave me access".

In 1965 Scully's first wife gave birth to a son, Paul, who later died in a car accident aged just 18. The same year he began a three-year course at Croydon College of Art in London. While here he came to admire artworks by Henri Matisse, Emile Nolde and Karl Schmidt-Rottluff and through their influence he developed a penchant for hard-won figuration (often consisting of dense layers of highly wrought paint).

On completing his studies at Croydon Scully went on to study art at Newcastle University. After discovering Abstract Expressionism, and seeing an exhibition of paintings by Mark Rothko at the Whitechapel Art Gallery in London, his gradually moved away from figuration towards abstraction.

While still a student, Scully followed in the footsteps of Henri Matisse, Paul Klee and August Macke, making a road trip to Morocco in an old truck with eight friends. There he was deeply attracted to the rich, warm colors and geometric patterns of textile prints. He said, "I saw the striped fabrics that the Moroccans dye [...] I saw those stripes everywhere [in the galabeyas and robes], and when I got back to work I was making grids from stripes of colour". Scully was so drawn to Moroccan culture he almost decided to stay for good: "The temptation not to return to an urban environment was powerful on me. It was a moment of extreme crisis when I almost did not return to England".

Scully did return, however, and graduated from Newcastle in 1972. He remained in the University as a teaching assistant, as well as teaching one day a week at the nearby City of Sunderland College of Art. In 1972, Scully was awarded the Frank Knox Fellowship to study at Harvard University in Cambridge, Massachusetts. On visiting the United States for the first time he was impressed by the expansive, large format and slick, controlled surfaces of Minimalist American painting and his work became more ambitious, with more rigid, controlled geometric patterns on a bigger scale. A series of group and solo exhibitions followed on his return to London.

Mature Period

In the early 1970s Scully achieved commercial success for his stylised, geometric "supergrid" paintings. Collapsing together influences from Moroccan textiles, the urban environment and Piet Mondrian's Boogie-Woogie series, his work featured intricate layers of complex patterns layered on top of one another. His grids were created by using masking tape to create tight, mechanical edges. But Scully was gradually losing interest in this style since he felt it had become too populist: "I was able to support myself through painting right from the beginning, but I became poor because I wanted to [...] make my work in some way profound" he said later.

On receiving the Harkness Fellowship award in 1975 Scully was able to move to New York City with his girlfriend, the artist Catherine Lee. Between 1975 and 1982 Scully invested a new energy into his art, saying, "I wanted to make something that was austere and very high-minded. I set the bar high". The paintings he made were sparcer, more monochromatic and philosophical, influenced by the dominant trends in New York, namely Minimalism, Conceptualism, and specifically the paintings of Jasper Johns, Agnes Martin, Robert Ryman, Gene Davis and Brice Marden. Indeed, he worked closely with Marden, absorbing and sharing ideas about simplicity, structure and movement before emerging with a freer, more emotive form of image making.

In 1978 Scully married Catherine Lee and decided to dedicate a painting to her every year. This resulted in a group of paintings now known as the Catherine series. Scully took on a teaching post at Princeton University, allowing him to remain in New York where he felt increasingly at home. Indeed, the city provided the ideal backdrop for his style of patchwork abstraction, as he explained, "In downtown Manhattan I look at the way people patch things. You can tell by the way a large plywood sheet has been nailed into place on a construction site that no one is reverent. Sometimes the metal patches on the sidewalk are even rougher. I see a sort of urban romance in the expedients that people use to keep a place like Manhattan together".

In 1980 Scully travelled to Mexico where he was inspired to bring more color and expression into his work, saying, "Along the Pacific Coast of Mexico, the people living in squarish houses paint them with big patches of blue or red or some other colour. Form gets distorted by a subjective response, and that redeems it. That's wonderful, like Minimalist painting gone wrong". The following year he decided to stop using tape to mask edges in his paintings, imbuing in them with a looser, softer surface.

In 1983 Scully became an American citizen. The same year, his 18 year old son from his previous marriage died tragically in a car accident, leaving the artist bereft and distraught. He said, "Basically, I went insane but didn't deal with it because I wanted to keep painting".

Throughout his grieving period Scully carved a niche for himself in America, infusing his earthy, sensual paintings with a deeply melancholic streak. Although the dominant trend by this time was Neo-Expressionism - or what Scully called "melodramatic figuration" - his contemplative, loosely-geometric abstractions offered a unique sense of physicality and character that made his art much loved by critics and buyers. He said, "My work had an aggression, a scale and metaphorical references that could compete with American figuration". His larger than life canvases made reference to the geometries in art that have existed for centuries, subjects ranging from early religious paintings, Giorgio Morandi's still life studies, Piet Mondrian and Mark Rothko's abstractions, Bridget Riley's Op Art lines and Jasper Johns' loaded, symbolic flag stripes.

Late Period

Throughout the 1990s Scully's career continued to flourish. He made several more visits to Morocco, including a trip in 1992 to make a BBC film on Matisse, who had visited Morocco in 1912-13. In 1995, he took part in the prestigious Joseph Beuys Lectures in Britain, Europe and the United States at the Ruskin School of Drawing and Fine Art at Oxford University in England.

After divorcing his second wife (Lee) he married the artist Liliane Tomasko in 2006. The pair had a son, Oisín, in 2009. Since then he has had several major solo and retrospective exhibitions in locations as far reaching as the United States, China, Italy, Germany, Switzerland and Austria. In 2015 Scully completed a permanent installation for the restored Santa Cecilia de Montserrat monastery in Barcelona. Speaking of his frescoes, he said, I wanted "to add a little joy to the chapel [...] because people always associate spirituality with great austerity and great deprivation and it doesn't have to be like that". The "Scully Chapel" has invited comparisons with the Matisse Chapel in the French Riviera and the Rothko Chapel in Texas, though Scully has refuted comparisons with the latter on the grounds that he thinks Rothko is "very depressing and bleak and [that] you have to wring the paintings to get anything out of them".

Scully has continued to experiment with new directions, expanding into three dimensions with a series of ambitious, monumental sculptures, including a series in Yorkshire Sculpture Park in England. In his recent paintings he has also returned to the figuration of his student days, as seen in a series of works that were influenced by his experiences as a father which he titled Eleuthera.

The artist currently lives and works in New York with his wife Liliane and their son in an established base in downtown Manhattan, a place which he describes as, "prosperous, ruthless and filled with exotic energy". He also has studios in Barcelona and Berlin, and as an escape from the city, a second home in the wild, Bavarian countryside south of Munich. His interest in the solidity of art continues today and he said in a recent interview, "A lot of people are interested in art as a form of entertainment or as a one-liner. I'm interested in mystic profundity, primitive utterance and the whole pathos of the history of painting. This is a deep ambition".

The Legacy of Sean Scully

Scully is known today for his vital contribution to American abstract art in the 1970s and 1980s, bucking the trend for figurative Neo-Expressionism in favour of a deeply personal, lyrical language.

His powerful, bravado paintings have contributed to the argument that abstraction is still a current and relevant language with endless possibilities, and his ongoing explorations into a Post-Minimalist language have strongly influenced the next generation of painters who continue to pursue avenues of possibility opened up by his practice. For example, Scottish artist Calum Innes' drip paintings share Scully's contrast between hard edge and loose paint, creating the same open and closed figure-ground relationships. Bernard Frize explores visible, geometric brushstrokes reminiscent of Scully's later paintings, with vivid colors and sleek surfaces creating a contemporary abstract language. Angela De La Cruz, Avery Preesman and Adrian Schiess all produce work that exists in the middle ground between painting and sculpture, giving many of their artworks a raw anti-figurative status. Phyllida Barlow's monumental sculptures, meanwhile, juxtapose grids and gestural expression, echoing much of Scully's work. Scully was elected a Royal Academician in 2013 and has been twice shortlisted for the Turner Prize (1989 and 1993).

Influences and Connections

- Calum Innes

- Bernard Frize

- Angela De La Cruz

- Adrian Schiess

- Phyllida Barlow

-

![Robert Ryman]() Robert Ryman

Robert Ryman -

![Brice Marden]() Brice Marden

Brice Marden - Catherine Lee

Useful Resources on Sean Scully

- Sean ScullyOur PickBy David Carrier

- Sean Scully: Bricklayer of the Soul: Reflections in CelebrationBy Kelly Grovier, Colm Toibín, Bono, Ai Weiwei

- Sean Scully: IonaBy Richard Ingleby, Sean Scully

- Sean ScullyOur PickBy Brian Kennedy

- Sean Scully: Wall of LightBy Michael Auping, Stephen Bennett Phillips, Anne L. Straus

- Sean Scully: The Architecture of ColourBy Uwe Wimczorek

- Sean Scully: Twenty Years, 1976-1995Our PickBy Ned Rifkin

- Sean Scully: A RetrospectiveBy Danilo Eccher and Donald Kuspit

- Sean Scully: Body of LightBy Arthur C. Danto and Jurgen Habermas

- Sean Scully: The Catherine PaintingsBy Carter Ratcliff

- Constantinople Or The Sensual Concealed The Imagery of Sean ScullyOur PickBy Sean Scully and Susanne Kleine

- Sean Scully: Catalogue Raisonne. Volume IIBy Sean Scully

- Inner: The Collected Writings and Selected Interviews of Sean ScullyOur PickBy Kelly Grovier and Sean Scully

- Sean Scully: Artist's Sketchbook (Cuaderno De Artista / Artist Notebook)By Sean Scully

- Sean Scully: Resistance and Persistence: Selected WritingsOur Pick

- Sean Scully: Vita DuplexBy Hermann Arnhold, Pia Muller-Tamm, Tanja Pirsig-Marshall, Kirsten Claudia Voigt

- Sean Scully: LandlineOur PickBy Hirshhorn, Melissa Chiu, Stephane Aquin, Patricia Hickson, Kelly Grovier

- Sean Scully: Paintings and Works on PaperOur PickBy Edward King

- Sean Scully Figure AbstractBy Museum Ludwig Cologne

- Sean Scully PaintingsOur PickBy Paul Glazebrook and Irving Sandler

- Sean Scully: Resistance and Persistence: Paintings 1967 - 2015By Philip (ed.); Scully, Sean Dodd

- Sean Scully. Land SeaBy Timothy Taylor Gallery

Ask The Art Story AI

Ask The Art Story AI