Summary of Ben Shahn

Ben Shahn's desire to create narrative art that focuses on social and political justice have come to exemplify Social Realism and the art of social consciousness. From his questioning religious teachings as a youth in Lithuania and up through the end of his life, Shahn remained true to his vision. He never failed to create artwork to draw attention to those for whom life was a struggle, and did so with dignity rather than pathos or sentimentality.

Accomplishments

- Prior to World War II, Shahn was a lead practitioner of what has come to be called Social Realism. Such art works are narrative, figurative, and illustrative of the poor, oppressed, or those who live at the margins of society. The guiding spirit of Social Realism is a commitment to humanism.

- Ben Shahn brought together different forms of visual culture to break down the barrier between mass media and fine art. In opposition to what Shahn called "the rules for pure art," the artist consistently inserted words, texts, and quotations into his artwork to emphasize the didactic nature of his art.

- Because of Shahn's apprenticeship and friendship with Diego Rivera, Frida Kahlo, and other prominent artists, he upheld the supremacy and universality of art over the false boundaries of nation states. Through his work with Rivera, Shahn serves as a conduit between the United States and the arts of Mexico which were all the rage in the 1920s and 1930s, but fell out of favor until its revival in the 1980s.

- Despite his rise in fame and prestige, Shahn remained committed to his audience and subject matter. Shahn never spoke down to the American people, rather he stood amongst the crowd and fought the same fights as they did.

Important Art by Ben Shahn

The Passion of Sacco and Vanzetti

This is the only easel painting out of Ben Shahn's series of twenty-three gouaches depicting elements of the trial and subsequent execution of the two Italian immigrants, Nicola Sacco and Bartolomeo Vanzetti who were accused of murder during a robbery in Massachusetts. At the time and still today, controversy surrounds the guilty verdict, with many believing that the men were condemned because they were anarchists and because of the overt anti-immigrant sentiments of the era. In this painting, the three members of the Lowell Committee who denied the defendants' appeal hold lilies as they stand over open coffins containing the bodies of Sacco and Vanzetti. Judge Thayer can be seen in the background staring out the courthouse window onto the scene.

Shahn submitted this easel painting to an exhibition organized by Lincoln Kirstein at the Museum of Modern Art in New York. The museum's Board of Trustees objected to Shahn's depiction of the Lowell Committee members who were friends to many of the museum's trustees. Despite the Board's demand that Shahn's works along with the equally objectionable works by Hugo Gellert and William Gropper not be shown, the many other artists in the exhibition and the curator Kirstein refused to participate if the three artists were banned. The show eventually moved forward including Shahn's work with many of the trustees resigning in anger.

The painting's topic provides an early example of Shahn's use of his art against social injustice. This work helped to establish him as one of the great Social Realist painters. Also in the development of this artwork, Shahn had begun to think sequentially about narration through art, a process which ultimately led him to paint his complex public murals. Rather than painting for himself as other modernists did, Shahn painted for the public and for the cause of Sacco and Vanzetti, while simultaneously drawing upon the cubistic forms of Picasso in his figures. Shahn successfully melds together the formal with the political in this work.

Tempera on canvas - Whitney Museum of American Art, New York

Untitled: Jersey Homesteads Mural

Ben Shahn's 45 foot long x 12 feet high Jersey Homesteads Mural recounts the grand narrative of the Jewish exodus to the United States (1880- 1924), the Jews' quest for a decent livelihood in the punishing sweat shops of the unregulated garment trade, and the importance of Jewish labor unions. The left panel begins in 1930s Germany where a Nazi soldier holds a sign warning Germans not to buy anything from Jews; this threatening image by Shahn was the only reference to Nazi Germany in any New Deal mural. Two women seen mourning at open caskets which contain Sacco and Vanzetti are positioned above a depiction of the registry hall at Ellis Island where the Statute of Liberty is visible through an open doorway. A group of immigrants walking off a ship include representations of Shahn's mother, artist Raphael Soyer, and Albert Einstein who leads the group and who was on the board of Jersey Homesteads. The center panel depicts Jews and other immigrants working in a non-union, unsafe sweatshop. Shahn, a champion of unions, next painted an image which closely resembled President of the CIO John J. Lewis but is not to be taken literally as a portrait. The labor organizer presents a speech and quotes one by Lewis: "One of the great principles for which labor and America must stand in the future is the right of every man and woman to have a job, to earn their living if they are willing to work." Shahn concludes the narrative with the right panel with a happier life in Jersey Homesteads housing development. References to the importance of unions, is made by a sign on the development's entrance reading "ILGWU," standing for the International Ladies' Garment Workers Union. In the final scene, a group portrait of the Jewish garment union leaders, along with New York Senator Robert F. Wagner who was instrumental in the creation of labor-reform laws, look over the blueprints for Jersey Homesteads.

Shahn received this mural commission from the United States Resettlement Administration's new 200 home development Jersey Homesteads project that was created to provide housing, work, and farming opportunities for Jewish garment workers wanting to relocate from New York City and Philadelphia; many had lost their jobs due to the devastation of the Great Depression. This expansive and detailed mural reveals Shahn's commitment to improving the human condition through narrative storytelling, and his great skill at creating complex compositions.

Fresco - Collection of Roosevelt Public School, New Jersey

Resources of America

Resources of America (1938-39) is a commissioned mural Ben Shahn completed for the Bronx Central Post Office in New York City. His companion Bernarda Bryson served as his assistant on the project. The New Deal Program's Treasury Section of Painting and Sculpture, whose purpose was to oversee the commission of the best art possible for new federal buildings, selected Shahn's as the winning design. For example, one of the thirteen panels portrays both an agricultural and an industrial worker, displaying one man stooping down low to pick cotton, and a woman working at spindles in a mill. The central panel which is placed on a higher plane than the other panel depicts American poet Walt Whitman speaking to an assembled group of workers and pointing to a text-filled blackboard. His long, white beard makes the poet resemble a combination of Moses and Karl Marx.

Although not intending to be controversial, the Bronx mural did indeed elicit harsh criticism due to Shahn's inclusion of a quote by Whitman who was then on the Catholic Church's Index of Forbidden Books. Originally Shahn planned to include text from Whitman's poem "Thou Mother with Thy Equal Blood" but when preliminary sketches of the mural were displayed at the Bronx Post Office, a local priest took notice. Shortly after, Reverend Ignatius W. Cox, an ethics professor at Fordham University, publicly denounced the mural in front of thousands gathered in a church as being a government statement against religion. Cox urged parishioners to join him in demanding the text be changed, and began a letter-writing campaign which garnered much press coverage. As, Shahn had agreed when taking the job to make changes if there were any objections, he switched the text to lines from Whitman's poem "As I Walk These Broad Majestic Days." Despite the successful reception to the altered mural, the experience made clear to the artist the weight of censorship and the power that even a few members of the public could exert over an artist's work.

Egg tempera applied to plaster - Collection of Bronx Central Post Office, New York

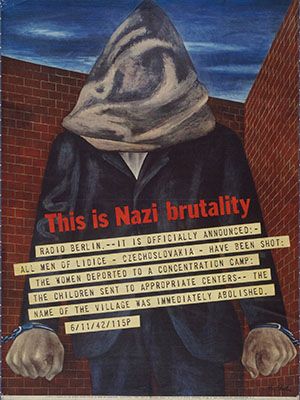

This is Nazi Brutality

In the early 1940s, Ben Shahn created paintings which became the basis of anti-war posters sponsored by the United States government. Shahn's This is Nazi Brutality is one of the most famous posters he designed during his position at the Office of War Information (OWI). In response to the Nazis total destruction of the town of Lidice, Czechoslovakia, and its inhabitants, Shahn's powerful image features a male figure whose head is covered by a hood and whose fisted hands, positioned firmly at his sides, are shackled. He stands beneath a dark and ominous sky and is backed both from behind and on his left side by a red brick wall. The title of the work as well as its theme are stated in bold red letters in front of the figure below which, the news of the event, as it was translated from a radio broadcast. The text reads: RADIO BERLIN.--IT IS OFFICIALLY ANNOUNCED: -ALL MEN OF LIDICE - CZECHOSLOVAKIA - HAVE BEEN SHOT: THE WOMEN DEPORTED TO A CONCENTRATION CAMP: THE CHILDREN SENT TO APPROPRIATE CENTERS--THE NAME OF THE VILLAGE WAS IMMEDIATELY ABOLISHED. 6/11/42/115P. Astonishingly, the OWI officials rejected Shahn's designs as too "violent" and "not appealing enough." Fed up with such disagreements, Shahn resigned after one year. Shahn's confrontational posture towards officials conveys a great strength of conviction in his topics.

Through the means of bold, graphic design, using an economy of words, coupled with an image freed from the types of details that typify Shahn's figural words, the reaction to this haunting work is powerful and viscerally felt.

Offset lithograph - Art Institute of Chicago

The Red Stairway

Ben Shahn's The Red Stairway is a powerful statement on destruction, hope, and the prevailing human spirit. An elderly man, wearing a black coat and hat, reliant on crutches, ascends a red staircase that winds up and then down the side of a ravaged building. In the right foreground, another man in a white shirt is rising up out of a crater carrying a basket of rubble.

As with many artists of his era, the horrors of World War II had a profound effect on Shahn and his work. In this and other paintings he chose to depict the devastation of the war symbolically, rather than as realistically or in a documentary vein. Here the man's journey up the stairs seems overwhelmingly arduous (as he is missing a leg) and is seemingly leading nowhere. This lack of hope echoes the oppressive weight of the effects of war and yet, Shahn is careful to also imbue the work with a sense of hope in the fact that the man attempts the journey at all. The other figure clears the debris and symbolizes Europe's own efforts to climb out of the destruction and metaphorically echoes the efforts of people to rebuild after the damages of the war. Even the blue cloud-filled sky is a bit lighter above this figure symbolizing the promised gift of another day that comes with each new dawn.

This painting is a key example of a major shift in Shahn's work in the postwar period. Prior to the war much of his focus had been on creating works of Social Realism but the war led Shahn to move his art towards the direction of a more "personal realism" resulting in works which offered the artist's own subjective response and feelings to the world around him. While his works became more emotional, unlike many artists of the period, Shahn still maintained a highly narrative and figurative style.

Tempera on Masonite - Saint Louis Art Museum

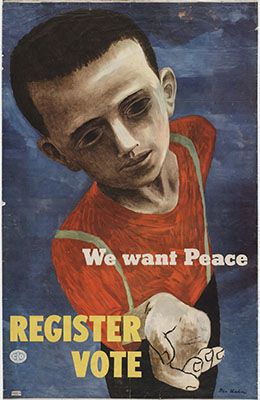

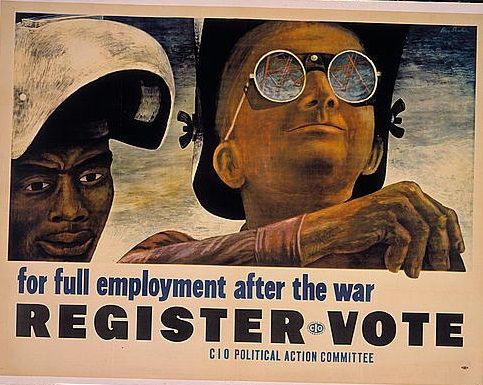

We Want Peace, Register to Vote

Throughout his career, Ben Shahn created numerous political posters; this work is an excellent example of the artist's graphic style. A powerfully stark image, the work depicts a gaunt young boy wearing dark pants, suspenders, and a red shirt with his right hand outstretched into the foreground in a pose of begging. His hollow, dark eyes look slightly downward preventing the viewer from a direct connection to his image. The purpose of the poster is made clear in the simple text which states: "We want Peace" and "REGISTER VOTE."

Shahn first joined the Congress of Industrial Organizations' Political Action Committee in order to reelect President Franklin Delano Roosevelt. After FDR's 1944 victory, Shahn became the CIO-PAC's director of the Graphic Arts Division. During this time he designed many posters to encourage Americans to get out the vote and to support the Democratic Party. Shahn's mastery in communicating his message is achieved by capturing emotions and the human spirit on the canvas as is the case with this work; such as the child's haunting eyes as he begs for a better tomorrow that can be achieved through the power of voting.

Shahn had a productive career as a commercial artist and illustrator, and felt there was an importance to being what he called a "communicative artist" and saw the power that reproducible works such as posters have in reaching a much larger and more diverse audience than that of a painting. Artist Andy Warhol is one who spoke of the great influence Shahn's illustrations had upon his own work.

Color lithograph poster - Collection of de Young | Legion of Honor, San Francisco, California

Allegory

Ben Shahn's painting Allegory features a red beast with both wolf and lion characteristics and flaming mane standing over a pile of four dead children's bodies. Neither the beast nor the bodies are anchored to anything rather they seem to float in a void of blue, red, and purple colors. In the left corner, a subtle hint of yellow seems to struggle through, echoing that of a sun behind clouds and; in the lower left corner of the canvas, Shahn depicts a group of bare red trees against a small patch of green background.

Shahn maintained that the inspiration for the painting was the story of a Chicago man, John Hickman who after his four children died in a tenement fire, killed the building's landlord who he believed was responsible for its start and received two years' probation after a manslaughter conviction. Shahn was commissioned to illustrate an article about the case for a Harper's magazine article in 1948. After the job ended and still thinking about the story, Shahn chose to explore the theme further on canvas. When the painting was first exhibited in 1948 it received some negative criticism including from The New York Sun's critic Henry McBride who maintained that the painting conveyed an anti-American sentiment and was paying homage to the Soviet Union. To McBride, the work was clearly communist since the beast was painted red. Shahn denied McBride's interpretation and maintained that the critic was erroneously misreading the painting.

As with many of his works from the mid-1940s on, Shahn also included many personal references such as the fire which dates back to his childhood. As a youth in Lithuania, Shahn watched his Grandfather's village burn to the ground, and later repeated the experience in Brooklyn, when his father rescued him and his siblings from a house fire which destroyed all their possessions, lost their financial stability, and ended up injuring his father. Wolves also had a personal association as his mother had told him stories of her being pursued by wolves while living in Russia. Highly symbolic, the work typifies Shahn's use of mythology and allegory to create his visual narratives.

Working in a more contemporary, expressive style, Shahn proves that both personal events, as well as tragic emotions, remain pertinent to modern art. While always exploring new forms and designs, Shahn always united these pictorial elements with deep narrative expressions.

Tempera on panel - Modern Art Museum of Fort Worth

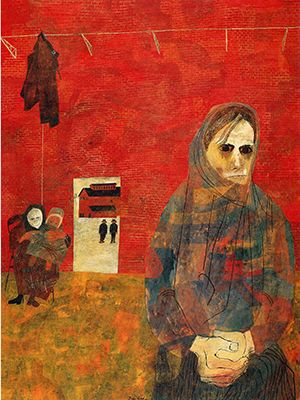

Miners' Wives

Ben Shahn was a union member, and remained committed to telling the stories, and the hardships of workers and laborers throughout his lengthy career. Shahn imbues Miners' Wives with a haunting sense of sadness. The artist depicted three figures in front of a red brick wall. The main focus, however, is the woman at right in the foreground, wrapped in a thin shawl, standing with arms clasped in front of her. Behind her another woman sits with a small child in her lap while above her a man's jacket and pants hang on a hook on the wall. In the background, visible through a rectangular doorway in the wall, two male figures in black coats and hats stand facing a building some distance behind them. The theme of the painting appears to be waiting for news of their husbands', miners, fates.

Shahn often drew inspiration for paintings from illustrations he had made for articles. The idea for this and five other paintings on this topic came from illustrations he was commissioned to create for a Harper's magazine article about the Centralia, Illinois mine disaster that killed 111 miners. The article was published in March 1948, and titled "The Blast in Centralia No. 5: A Mine Disaster No One Stopped." Long after its publication, the fate of the miners and their families stayed with Shahn; he felt compelled to use his art to further their story. In this painting, Shahn concentrates on the wives' agony as they wait endless hours for their husbands to return home, and then, depicts the harsh reality of their lives as widows. The two men in the distance, while ambiguous, perhaps represent the messengers of this tragic news.

The topic of mines was familiar to Shahn as he himself had gone into mines earlier and his second wife grew up in a mining area. Further, Shahn was a lifelong supporter of laborers and unions, such as the United Mine Workers Union. Possessing a personal connection to the subject, this painting demonstrates Shahn's expertise as a figurative, realist artist, mastery at creating works that emotionally connected with viewers and his ability to capture the stories of important current events.

Egg tempera on board - Philadelphia Museum of Art

We Did Not Know What Happened to Us

This is one of a series of works by Ben Shahn collectively known as the Lucky Dragon paintings. The series includes some of the most profound and darkest imagery that Shahn ever created. At the top center of the canvas, a beastly face with mouth open and teeth bared is looking out towards the viewer with multiple clawed arms and feet barely visible in a tangled swirl of white cloud-like lines amongst a sea of black. Below the creature, two figures are visible from the waist up, arms outstretched as the figure on the left tries to cover his mouth with one arm.

Shahn's prolific career as an illustrator often provided inspiration for his paintings as was the case with this work. In 1957, Shahn was commissioned to illustrate a series of articles for Harper's magazine about the crew of the Japanese fishing boat the Lucky Dragon who were trapped in a shower of radioactive debris on March 1, 1954 - after America tested a hydrogen bomb in the Pacific Ocean. All twenty-three members of the crew suffered the effects of radiation poisoning with one member dying after a long period of suffering.

Shahn was very troubled by the story and its grave injustice. The artist was a strong peace advocate who denounced nuclear weapons. Wanting to make a strong statement opposing nuclear weapons, the series of paintings he created consisted of eleven works depicting the tragic event and the aftermath. This particular painting focuses on the nuclear blast itself which is portrayed as a violent creature amidst clouds of lethal poison. Well received when exhibited and even reproduced as a book, the Lucky Dragon series demonstrates that while Shahn had a versatile and rich career, he never strayed far from his political ideals and his strong sense of ethics. Created late in his life, the work was part of the last series of Shahn's career. Rather than overt agitprop art, or loud social protest art, Shahn softens his style and message in order to let the tragedy speak directly to viewers. His is a quiet emotionalism not always conveyed through contemporary art.

Tempera on wood - Smithsonian American Art Museum, Washington DC

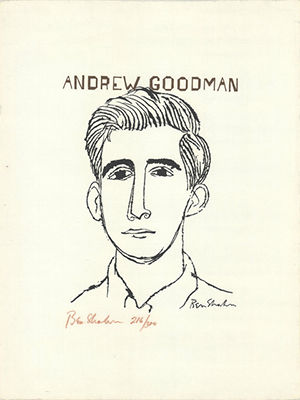

Andrew Goodman

Part of the Human Relations Portfolio series, Ben Shahn drew images that paid homage to slain civil rights activists James Chaney, Andrew Goodman, and Michael Schwerner who were murdered by the Ku Klux Klan in 1964. Using a spare, calligraphic line which emphasizes Goodman's youthful facial features, all of the 3 works depict the men in traditional, somber bust portrait. The simple elegance of each work is achieved in part by the lack of color, with Shahn choosing to render each figure only in black lines. The simplicity of Shahn's line and decision to work with outline when delineating the 3 men, serve to quell the heat and anger of the Civil Rights struggle. The work emits a sense of quiet that invites reflection; the image, although addressing death, speaks as well to peace.

Screenprint on paper - The Jewish Museum, New York

Biography of Ben Shahn

Childhood and Education

Born into an Orthodox Jewish family, Shahn witnessed both anti-Semitism and political persecution during his childhood in Lithuania. The Tsar's forces arrested Shahn's socialist father and imprisoned him in Siberia. As a young boy, Shahn began to take a stand against social injustice, a moral stance that would define his life's work. While as a youth studying the Bible, he accused God of acting unjustly when he struck a man dead who had disobeyed his command in the story of the building of Solomon's Temple. Initially, Shahn refused to return to religious school until the teacher would acknowledge this injustice; later, he only returned because of the urging of his beloved grandfather. In 1906, when Shahn was 8 years old, his family immigrated to New York and reunited with his father who had long since escaped and settled in Brooklyn. The year 1906 was the peak year of Eastern-European Jewish migration to America so Shahn's is very much an immigrant's story. While a child back in Lithuania, Shahn first became interested in art; but, as resources were scarce, he had to draw on the pages of his books.

In Brooklyn, his American fifth-grade teacher noticed and encouraged Shahn's nascent artistic talents. One year later he received his first paid art job writing names on graduation diplomas, the first time a student had been given such an honor. Despite his obvious talent, Shahn's mother demanded that Shahn forego a high school education and instead get a job and help the financially strained family. His mother's actions caused irrevocable damage to their relationship. Fortunately Ben Shahn obtained a job that nurtured his artistic growth as an apprentice in his uncle's lithography shop, where he developed his love of letters, a life-long fascination and talent; by age 19 Shahn was a professional lithographer. In addition to taking art classes at the famed Educational Alliance on New York's Lower East Side, Shahn continued his education through self-study and night classes. By the fall of 1919, Shahn had earned enough money to pursue a college education and proceeded to study at New York University, the College of the City of New York, and the National Academy of Design.

Early Training

In 1922, after Shahn's marriage to Tillie Goldstein, who had been a suffragette and political activist, the artist resumed work as a lithographer. Concurrently, he continued to train as an artist, and took two lengthy trips to Europe and North Africa to study the environs, people, and the Grand Paintings of Europe. During the second, highly productive trip in 1928, he had created more than two hundred watercolors and drawings.

Once back home in Brooklyn, Shahn began working full-time creating paintings, manuscript lithographs, and photographs. Having basically taught himself photography - with a modicum of advice from his friend and celebrated photographer Walker Evans - and in need of a good camera, Shahn made a deal with his brother to buy him one which Ben would give back if he failed to get a photo published from the first roll of film he took. Determined, as alway, Shahn won the bet when in 1934 a photo of a theater group performing on a New York City sidewalk was published in New Theatre, a radical arts magazine.

In 1933 famed Mexican Muralist Diego Rivera hired Shahn, along with several other promising artists, to apprentice on his mural Man at the Crossroads at the newly constructed Rockefeller Center; young Nelson Rockefeller first commissioned the premiere Mexican muralist, but later destroyed his unfinished fresco due to Rivera's inclusion of a portrait of Lenin. Under Rivera's tutelage, Shahn learned the demanding art of fresco or painting with dry pigments on wet plaster. With the formation of the New Deal Arts Program under FDR, Shahn would pursue several mural commissions but was not successful until 1936, when the painter secured a commission for the community center of Jersey Homesteads. Homesteads, now called Roosevelt, New Jersey, was a government funded cooperative housing development built for Jewish garment workers from New York City, the majority of whom were political radicals. Shahn and his second family with artist Bernarda Bryson would make Homesteads their home.

Often Shahn created work to protest social injustice, such as the infamous trial and execution of Sacco and Vanzetti. During the 1930s and the FDR era, Shahn worked as a photographer and graphic artist for the federal government's Resettlement Administration. Shahn sought to photograph the dire living and agricultural conditions that poor Southerners struggled under. He would later go on to work as a graphic artist in the Allied forces during World War II for the Office of War Information, also a government agency.

Mature Period

With the devastation caused by World War II, and the mass execution of six million fellow Jews, Shahn turned away from Social Realism and towards what he came to call "personal realism." While still working with the human figure, Shahn's paintings became less about society as a whole and turned much more personal and symbolic. Gaining further recognition with the public and the art world, in 1947 he became the youngest artist to have a retrospective at New York's Museum of Modern Art. In sharp contrast to the Abstract Expressionism that was increasing in popularity, and despite some critics' negative reviews, Shahn's realist works had broad appeal.

Shahn's work often had a progressive political bent that, at times, courted controversy. Active on the Left, he was eventually investigated by the FBI which accused him of producing artwork for Communist newspapers and magazines, and belonging to Communist art organizations during the 1930s (when to do so, in fact, was legal). In 1959, during the McCarthy Witch hunt and the Cold War era, Shahn bravely refused to testify before members of the House Un-American Activities Committee, and in doing so protected other artists on the Left. In an attempt to humorously turn the tables a bit, during one investigative visit by the FBI to Shahn's home, the artist decided to go over-the-top in making them welcome offering them lunch, introducing his daughter, and engaging in long conversations which made it impossible for the agents to quickly leave despite their obvious discomfort. Regardless, the FBI maintained an active file on Shahn up until his death.

Later Period

Shahn had a prolific career as a graphic artist. He was an illustrator for CBS television and for such national magazines as Esquire, Harper's, and Time. He also returned to his Jewish roots by creating mosaic murals for several synagogues. All the while, the pursuit of justice through art remained his main concern. Shahn responded to the 1954 tragedy on the Lucky Dragon fishing boat in which the fishermen suffered the effects of radiation from America's testing of the hydrogen bomb, by painting a series depicting the men and the nuclear effects on their bodies. Teaching was also important to Shahn and while at Harvard University for the 1956-57 academic year, he presented six lectures on art, which were later published as The Shape of Content (1957); impressively, the book remains in print and provides much insight into his artistic beliefs and practices, and the life of an artist.

In 1969, Shahn died of a heart attack shortly after having surgery to remove a tumor on his bladder at the age of seventy. The artist had remained active throughout the last years of his life.

The Legacy of Ben Shahn

Ben Shahn's use of his art to counter social and political injustices came to exemplify Social Realism and socially conscious art. His works narrate the plight and struggles of many living in the 20th century while simultaneously providing the foundation for future generations of politically committed and figurative artists such as Leon Golub and muralist Mike Alewitz. Shahn passionately believed in the role of art to help serve the human condition, to point out injustices, and to draw alliances rather than create dissention. Other artists whose work was tied to social movements such as the Black Civil Rights Movement, the Anti-Vietnam War Movement, and the fight for reproductive freedom, find both a visual and philosophical predecessor in Shahn's lengthy career.

Influences and Connections

-

![Meyer Schapiro]() Meyer Schapiro

Meyer Schapiro -

![Walker Evans]() Walker Evans

Walker Evans ![William Carlos Williams]() William Carlos Williams

William Carlos Williams

-

![Alfred H. Barr, Jr.]() Alfred H. Barr, Jr.

Alfred H. Barr, Jr. ![William Carlos Williams]() William Carlos Williams

William Carlos Williams

Useful Resources on Ben Shahn

- The Shape of ContentOur PickBy Ben Shahn

- Portrait of the Artist as an American, Ben Shahn: A Biography with PicturesBy Seldman Rodman and Ben Shahn

- Ben Shahn's New Deal Murals: Jewish Identity in the American SceneBy Diana L. Linden

- Common Man, Mythic Vision: The Paintings of Ben ShahnOur PickBy Susan Chevlowe

- The Complete Graphic Works of Ben ShahnBy Kenneth Wade Prescott

- The Photographs of Ben Shahn: The Library of Congress (Fields of Vision)By Timothy Egan

Ask The Art Story AI

Ask The Art Story AI