Summary of Florine Stettheimer

A pioneer artist from early twentieth-century New York, Florine Stettheimer advanced new possibilities in painting for women artists. Drawing on influences from European avant-garde arts, literary modernism, and the theater, Stettheimer's aesthetic vision presents a signature mix of the whimsical and the decorative with a sharp eye for composition developed through her knowledge of art history and understanding of the latest artistic movements. Although they often veer toward the fantastical, her paintings also provide a slice of artistic and social life in pre-World War II New York, celebrating the city's creative energy in a bygone era.

Accomplishments

- Among her circle of friends, Stettheimer was admired for her unique sensibility and style; her paintings provided a vision of a life lived as art. Once derided as "ultra-feminine," today they're celebrated for their embrace of femininity as an act of empowerment.

- Stettheimer's unique aesthetic of "lightness, lace [and] feminine sensibility" provided a radical antidote to "patriarchal infallibility," noted feminist art historian Linda Nochlin. Her work serves as a counterpoint to the predominant narrative of modernism that only celebrated the accomplishments of male avant-garde artists.

- In addition to making art, Stettheimer played an important cultural role, holding cosmopolitan salons in her home and studio that welcomed emigré artists from Europe as well as nurtured homegrown talent.

- Led by women such as herself and her sisters, Stettheimer's salons became a historically unique space of freedom, where women and queer men could gather as themselves.

The Life of Florine Stettheimer

Due to their Jewish heritage, Stettheimer and her family were excluded from New York high society. But that outsiderness led them to appreciate and celebrate individuality and eccentricity, becoming, as the critic Peter Schjedahl puts it, "doyennes of liberty."

Important Art by Florine Stettheimer

Model (Nude Self-Portrait)

Measuring four feet high and over five feet wide, Model (Nude Self-Portrait) is a larger-than-lifesize rendering of Florine Stettheimer in an alluring and powerful pose. The forty-five-year-old artist painted herself reclining on a bed with delicate, flowery bed linens. She rests her head on the tips of her fingers, while holding a bouquet of flowers in the other hand. Her head is turned nonchalantly. She looks out as if daydreaming. In this striking and unusual self-portrait by a woman artist, Stettheimer took ownership of her nude body. The significance - and bravery--of this self-representation may be missed by audiences today, but, as art critic Max Pearl notes, she painted this work "at a time when women were arrested for wearing bathing suits that stopped above the knee." Here Stettheimer embraced her feminine figure even as she also proclaimed a politics of "New Woman" and liberation that was a progressive current in her time.

Model (Nude Self-Portrait) alludes to Édouard Manet's 1863 painting, Olympia, but is likely more a commentary than an homage. Barbara Bloemink, a leading scholar of Stettheimer's life and art, notes, "Her expression [...] is not confrontational but knowing, even slightly mocking - an acknowledgment that the portrait is not predicated on the voyeuristic gaze of her male viewers [such as in Olympia and the typical female nude in Western art], but is the subject of a mature woman's experience of her own body and ultimately an exaltation of femaleness." Rather than merely putting her body on display, Stettheimer expresses her authority, pride, independence, and beauty on her own terms. She challenges the gender status quo by connecting sexual prowess with bodily autonomy. The omission of the black maid figure in the Manet, furthermore, speaks perhaps to a different politics of race. She does not need a maid, much less a racialized other, to bring her the bouquet and serve as a foil to her body. Instead, she holds her own flowers, almost enticing the viewer with them.

Oil on canvas

Soireé

This interior scene depicts several notable individuals who were integral to Stettheimer's social circle - here gathered in her studio for one of her salon evenings. Guests include artists Albert Gleizes and Gaston Lachaise and writers, poets, and playwrights Ettie Stettheimer, Avery Hopwood, and Sankar. The influential modern art critic and collector, Leo Stein, is situated on a red rug in the center of the floor, likely signifying his professional authority and status as a tastemaker. However, as arts writer Alexxa Gotthardt notes, "it's Stettheimer who is clearly lording over this universe from her perch in A Model (Nude Self-Portrait)," displayed in the back for her guests' enjoyment.

A table of food and drinks is placed on the lower edge of the canvas, and guests are spread throughout the room. They are depicted from a flattened, raised perspective, a pictorial device influenced by French avant-garde painters such as Matisse that Stettheimer made use of often in her portrayals of social scenes. In Soirée, in particular, traces of Matisse's signature interior views such as The Red Studio (1911) are evident. Like his work, Stettheimer's painting contains pictures within pictures and points toward a dissolution of spatial illusion. Unlike Matisse's studio devoid of people, however, Stettheimer's brims with conviviality. As Bloemink analyzes, "The objects and the surrounding space interpenetrate each other. By creating an interdenominative space where objects and surfaces imperceptibly blend, Stettheimer, like Matisse, gives equal importance to the tactile and the visible, investing both with expressive meaning."

The painting's formal innovation is especially significant in the context of American art in the early twentieth century. As Pearl notes, "Art in the United States in the period between the two world wars was bounded by two opposing pillars: social realism and abstraction." Stettheimer provided an alternative path, through which modernist compositional technique blended with abstracted figuration, rendering a space that is both "real" and whimsically airy, evoking the leisurely mood of the salons.

Oil on canvas

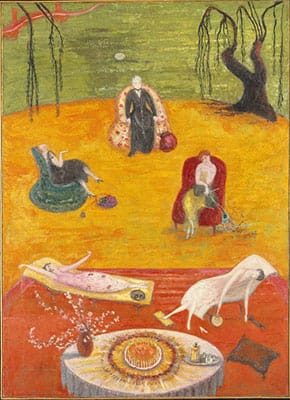

Heat

Among her generation of artists, Stettheimer stood out through her unique approach to portraiture, especially group portraits, writes art historian Francis M. Neumann. She notes, in particular, Stettheimer's "emphatically personal subject matter" and formal choice, which evokes a form of "aestheticism," that is, a view of the world through "a degree of artifice, of stylization."

Heat is a metaphorical scene of life in the summer's sweltering heat and humidity. The setting is a birthday party for Rosetta Walter at the Stettheimers' summer house in the hamlet of Bedford Hills, New York. Florine, her mother and sisters Carrie, Ettie, and Stella are the subjects in this painting. At the top, Rosetta, the matriarch, sits in a patterned armchair. Going clockwise, the next figure depicted is Carrie, who is holding a knitting needle and yarn or thread, which is draped across her knee. She appears to be nonchalantly looking at her nails. Florine is the next subject, and she is clearly feeling the heat exhaustion - she is languishing in a white lounge chair, practically slinking off the edge. A cat is clawing at her draped hand as if to try and wake her up. To Florine's left is Ettie who is also lying in a lounge chair, with outstretched arms. A black cat lies curled up at her feet. Further up, Stella has her back turned to the viewer, she looks like she is engaged in conversation. A ball of yarn has rolled out of her purse. In the painting's foreground there is a table with objects celebrating the occasion of Rosetta's birthday. The centerpiece is the cake, which, looking like the center of a hefty bloom, seems to be radiating light. On it a message in piping reads "Many Happy Returns."

Although, as Pearl notes, European Surrealism never completely took off in the United States, Heat demonstrates Stettheimer's embrace of a Surrealist sensibility. The subject matter is one perhaps of a somewhat altered state of consciousness: somewhere between dreaming, sleep, and languor. The painting, furthermore, eschews conventional perspectival rules. Each figure, no matter how close or far she is situated on the canvas, is portrayed on a similar scale. Rather than painting a realistic background, Stettheimer placed her figures on top of tri-color bands, essentially creating an abstract color field for the background. It anticipated mid-century Abstract Expressionist painters' use of painterly regions of color as a means to influence the viewer's affective response (such as in the work of Barnett Newman and Helen Frankenthaler). Here the top section features a hazy green atmosphere suggestive of extreme humidity; the middle section is a yellow-orange hue and the bottom is a bold red-orange, each evoking the scorching effect of the sun's heat waves.

Oil on canvas

Asbury Park South

Asbury Park South features a scene of activity in the seaside city of Asbury Park, New Jersey. Like many of her paintings, there are various narratives happening all at once with multiple figures engaging in different leisurely pursuits. The two lithe dancers in the middle of the scene, in particular, command attention with their graceful movement and skin-bearing costumes. The painting is notable among Stettheimer's works for its depiction of Black life in America during the 1920s.

Throughout much of its history and during the time this painting was made, Asbury Park had been a segregated city. On Stettheimer's racial politics, art historian Linda Nochlin writes, "Although Stettheimer can hardly be counted among the ranks of notable activists in the cause of racial equality, it is nevertheless true that black people figured quite regularly in her work [...] Her sympathy for black causes can, in addition, be inferred not merely from her work but from her close friendship with one of the staunchest supporters of Black culture, the music critic, belle lettrist and bon vivant, Carl Van Vechten." Van Vechten, who was a white man, documented the Harlem Renaissance through his photographs, and was a patron of many notable artists from the scene. In the painting, Stettheimer seems to suggest his role as observer and supporter, painting him upon a raised platform with his arms crossed, overlooking the crowd below.

Stettheimer accompanied Van Vechten to many of the Black neighborhoods he worked in, including the segregated beaches and clubs of Asbury Park. Her choice to paint this scene was both a means to show the virtue, class, and dignity of the Black community, as well as to express solidarity in the fight for desegregation. Art historian Barbara Bloemink explains the significant role Asbury Park had in the history of racial equality in the US: "The segregated south side [...] had gained national acclaim during the late nineteenth century as African-American residents actively resisted early attempts at segregation from using the main beach along with white tourists - bringing reporters from across the United States to cover the story."

In Stettheimer's painting, both white and Black individuals are seen congregating together, a scene of racial harmony that was far from the reality of that era.

Oil on canvas

Spring Sale at Bendel's

Stettheimer's affluent lifestyle included an appreciation and knowledge of fashion. The painting's style here draws on 1920s fashion illustrations in magazines such as Vanity Fair, with lithe figures and long curvaceous lines providing a sense of elegant airiness. Yet critics have also pointed out how Stettheimer inserted in her work a critical attitude toward vanity and consumer culture. Spring Sale at Bendel's is a dramatized narrative and caricature of the New York upper-class. The painting illustrates a humorous scene taking place during a sale at Bendel's, a woman's luxury department store that was located at 712 Fifth Avenue in Manhattan.

Stettheimer has set up the canvas like a stage, framed by the winding carpeted stairs to the left and the red satin curtains to the right. The figures are placed as if in a raucous ensemble scene from a Broadway comedy. Shoppers are enticed by the excitement of the sale and are seen grabbing from a bin of colorful scarves in the center. Throughout the painting, various customers are trying on items of clothing, modeling their wares in the mirror, looking ostentatious and perhaps overly pleased with themselves. Her all-black clothing suggesting a uniform, the left figure in the foreground is carrying numerous garments that her customer is presumably choosing from. She stands still amidst all the commotion and frenzied movement of Bendel's clientele. Her facial expression unreadable, she observes what's in front of her like a surrogate for the painting's viewer. Placing herself as an observer, Stettheimer signed the painting using her initials on a monogrammed sweater worn by a Pekingese dog, who sits at the bottom of the staircase on the left-hand side of the canvas.

In her important essay on Stettheimer entitled "Rococo Subversive," Nochlin expounds on the "self-contradictions" in Stettheimer's life and oeuvre. On the one hand, a painting such as Spring Sale showcases a "fantastically Rococo" pictorial arrangement, referring to the eighteenth-century French artistic style that prioritized lightness, ornamentation, and display of luxury. On the other hand, the scene casts a critical eye on the frenzied transactions rather than keeping with the Rococo, aristocratic fantasy. As Nochlin writes, Stettheimer "was a snob but an ardent New Dealer, a fanatic party-giver who in her diary complained of a particularly spectacular party given in her honor that 'it was enough to make a socialist of any human being with a mind.'" Nevertheless, such contradictions are not as paradoxical as they may sound, as Nochlin also points out. Stettheimer may represent an extreme case of a familiar story in avant-garde culture: its oftentimes antagonistic relationship with the status quo that in many ways are afforded by proximity to socio-economic privilege.

Oil on canvas

Four Saints in Three Acts

Stettheimer's set and costume design for the opera Four Saints in Three Acts was her only theater design work that was actually realized on the stage. Yet, its inventiveness in both the material used and aesthetic vision has stood the test of time. It is now seen as a major piece of avant-garde theater design in the twentieth century.

A collaboration between the composer Virgil Thompson and modernist poet Gertrude Stein, the opera exemplified Stein's literary experiment with emptying language of traditional contents. Stein was, explains curator Frank Smigiel, "concerned more with the sound of words than with plot." This exploration of linguistic "pure form" was echoed, scholars have noted, in the set design by Stettheimer. For the production, she stretched out 1,500 square feet of sky-blue cellophane to serve as a backdrop, creating striking glittering effects with white lights shining on them from above the stage. The scenery evoked, writes scholar Judith Brown, "a sky hung with a rock crystal." "It defied comparison," notes arts writer Steven Watson, "to anything the audience had ever seen."

In 1934 cellophane was still a relatively novel material, used for commercial packaging and featured in popular culture such as Hollywood movies as a signifier of "the slickly modern." Stettheimer's use of it here was likely the first instance that cellophane appeared in a high-brow theaterical context. Stettheimer had embraced the material before as decoration for her own living space. "It was chic, glamorous, and trendy," explains Brown. But beyond that, the use of it signals "the mixing of high and low, popular culture and avant-garde" that was very much part of Stettheimer's visual world. In her apartment as on the stage, on the performers' costumes and in her paintings, Victorian lace and cellophane comingled.

Featuring an all-black cast - considered provocative and "modern" then - the opera went on to a successful commercial run on Broadway. A contemporaneous critic reflected on its positive reception: "Four Saints in Three Acts is a success because all its elements - the dialogue, the music, the pantomime, and the sparkling cellophane décor - go so well with one another while remaining totally irrelevant to life, logic, or common sense," in keeping with Stein's play with language. Stettheimer experts Irene Gammel and Suzanne Zelazo note: "Stettheimer's designs mirrored Stein's dissolution of scenic conventions, contributing to the promise of strangeness that was part of the opera's public appeal."

Stettheimer's designs were so influential and well received that stores along New York City's glamorous Fifth Avenue began to offer cellophane dresses and window displays inspired by her sets.

Performance photograph by White Studio - New York

The Cathedrals of Art

In her later years, Stettheimer painted a series called Cathedrals, depicting secular landmarks of New York City. The Cathedrals of Art is the last work in the series. Despite the incredible amount of detail, the painting is actually unfinished. Stettheimer continued working on it up until her death in 1944. Among the Cathedrals painting, this work carries the most personal content, providing a window into the New York art world that she had been a part of and from which she drew much inspiration and enjoyment.

A composite scene, The Cathedrals of Art combines the backdrops from her prior Cathedral paintings of three major New York City art museums, namely: The Metropolitan Museum of Art, The Whitney Museum of American Art, and the Museum of Modern Art. It is as if she wanted to create a fantasy museum by curating in iconic works from each museum. The texts along the two main columns, "Art in America" and "American Art," speak to Stettheimer's pride in the homegrown artistic vanguards. In addition to artworks, many of New York's key artists, critics, and museum professionals are congregating within the large hall-like setting.

All three heads of the depicted museums are present. On the top left is Alfred Barr of the Museum of Modern Art, who sits in a modernist style chair with the word "Modern Art" painted beneath him. Between the columns we find Francis Henry Taylor of the Metropolitan Museum of Art, holding hands with a sashed "Baby Art," as Stettheimer humorously called the figure, while touring some works from his museum's collection. And, on the right side, Juliana Force of the Whitney Museum stands beside a statue of Gertrude Vanderbilt Whitney, the museum's founder. Stettheimer depicts herself at the bottom right hand corner, standing beneath a fanciful canopy. Adorned with vibrant flowers, she is striking yet demure, separated from the rest of the scene, a fitting metaphor of how she conducted herself in the art world: wielding influence yet staying away from the limelight. Beside her is the outspoken art critic, Henry McBride. He is holding up flags with the words "stop" and "go" in each hand, showing how the art critic is always exercising his authority and ushering in the latest trends. The photographer Alfred Stieglitz is also featured: he dons a black cape and stands at the foot of the central staircase. In the foreground, there is a whimsical scene of fashion photographer George Platt Lynes photographing another "Baby Art," as a Madonna-like figure, kneeling at the bottom of the canvas, looks on adoringly. The flash from the camera creates a halo of artificial light around Baby Art's head, alluding to art historical nativity scenes depicting the birth of Christ. Stettheimer, who was Jewish but not observant, has created her own divine narrative, centered around what she considered to be modern day shrines and sites for holy pilgrimage.

While traditionally a painting in the Western art tradition provides a window onto the world with a singular scene, Stettheimer liked to include multiple figures (and sometimes the same figures) in one painting, denoting different temporalities (a pictorial device more often employed in Eastern arts). According to Gammel and Zelazo, her friend Duchamp called this simultaneity "multiplication virtuelle," virtual multiplication. "Paintings such as these compress both perspective and time, in that they depict sequential events over the course of a day and night," explains Pearl. Somerville argues that this pictorial device in Stettheimer can be understood in tandem with Stettheimer's reading of the French philosopher Henri Bergson's New Vitalism: the view that "life was a continuous flowing of events rather than a succession of singular isolated moments and that one should embrace the essential sensations of being and change."

Oil on canvas

Biography of Florine Stettheimer

Childhood and Adolescence

Florine Stettheimer was the fourth of five children born in the city of Rochester, New York to Joseph and Rosetta (née Walter) Stettheimer. Her mother was of German-Jewish heritage and had an affluent upbringing thanks to the family's banking business. Joseph abandoned the family, leaving Rosetta to raise the children on her own. The matriarchal household proved to be a foundational setting for Florine who expressed strong feminist views as an adult.

Florine was especially close with her sisters, Carrie and Ettie, who shared an affinity and passion for the arts. The Stettheimer sisters' artistic inclinations were supported by their mother, who split the family's time between New York City and Europe, where they had ample access to cultural experiences and renowned works of art.

Early Training and Work

From around ages ten through fifteen, the family lived in Stuttgart, Germany, where Florine studied art at the Priesersches Institut from 1881 to 1886. In 1890, the family moved back to New York City, and in 1892, Florine enrolled in the Art Students League, where she studied for four years. Her teachers included Carroll Beckwith, Harry Siddons Mowbray, and Kenyon Cox. During her formal art school studies, she developed skills and techniques for painting and drawing live models, enrolling in the first ever live drawing class for women in the city.

At the turn of the century, the Stettheimer family returned to Europe on an extended stay (1898 to 1914), where they traveled across Germany, France, Switzerland, and Italy. Stettheimer immersed herself in European culture, especially in Paris, a key hub of modern art. She was captivated by the French avant-garde art scene and attended philosophical lectures by Henri Bergson. Her early paintings at this time incorporated influences of then major art movements including, Neo-Impressionism, Symbolism, and Fauvism. In addition to visual art, she was drawn to modern ballet, most notably, Sergei Diaghilev's Ballets Russes and the company's set and costume design by artists such as Léon Bakst. The Ballets Russes' interdisciplinary aesthetic vision struck a chord with her, and she would later realize a total aesthetic environment in her living quarters and exhibition. In 1912, inspired by the company's production of L'après-midi d'un faune, Stettheimer began working on her own libretto and designed costumes for the ballet she conceived called Orphée of the Quat-z-Arts. The ballet was never produced, but her fantastical designs for it remain well appreciated among art lovers to this day.

Mature Period

In 1914, the Stettheimers returned to New York City at the outbreak of World War I. In 1926, Rosetta, Florine, Carrie, and Ettie moved into the opulent French Renaissance-style Alwyn Court building on West 58th Street. Among their artistic circle, the building became synonymous with the sisters and their cosmopolitanism. Due to the War in Europe, a number of key European avant-garde artists moved to New York City around this time. Stettheimer became especially close friends with Marcel Duchamp, who taught her and her sisters French. Regarding Florine and her two sisters, Duchamp later wrote, "they were so funny, and so far out of what American life was like then." Other artistic members of her inner circle included Georgia O'Keeffe, Alfred Stieglitz, Albert Gleizes, Edward Steichen, Gaston Lachaise, and the writer Carl Van Vechten, among others. The three Stettheimer sisters were revered as salonistes. Holding a salon - an informal evening at home where friends, artists, writers, musicians gathered - was an imported tradition from European high society. The Stettheimers were not the only ones holding them in New York, but theirs was especially well known among a select group of the city's artistic luminaries. Unlike other salons at the time, LGBTQ guests did not have to conceal their identities at these events. The Stettheimer salons were a "sanctuary" and a unique aesthetic space, as art historian Cécile Whiting explains, where the interiors echoed the refined sensibilities of the attendees. Held in their apartment as well as in Florine's studio in the Beaux-Arts building (now known as the Bryant Park Studios), the evenings contributed to the city's thriving Jazz Age creative community as well as the rising tide of queer modernism in New York. Stettheimer's personal life and sexuality remain unknown as her sister edited out any information that might relate to it from her diary entries after her death. However, her outlook as a progressive and independent woman - as well as her awareness, as noted in her diary, of antisemitism - most likely contributed to her embrace of other marginalized groups such as her queer friends.

Also at their salons, Florine would typically preview a painting prior to contributing them to group exhibitions. She began these intimate art previews in 1916, calling them "Birthday Parties." Apart from being her confidants and critics, her friends became muses for many of the paintings she made. In a poem titled "Our Parties," she expresses her enthusiasm for representing her friends in her works of art: "Our Parties / Our Picnics / Our Banquets / Our Friends / Have at / last a raison d'etre / Seen in color and design / It amuses me / To recreate them / To paint them."

In 1915 Stettheimer painted one of her most revolutionary works of art, Model (Nude Self-Portrait), which is a modern and feminist riff on Manet's famous 1863 painting Olympia. The painting depicts the forty-five year old artist provocatively posed naked on a bed while holding a bouquet of flowers. Stettheimer's fully nude self-portrait was one of the first of its kind painted by a woman artist. Other intimate subjects that started to appear during her mature period included her family (mostly her mother, Carrie, and Ettie) and friends in the arts, such as Marcel Duchamp, Carl Van Vechten, Alfred Steiglitz, Edward Steichen, and Henry McBride. Although Georgia O'Keeffe does not appear in any of Stettheimer's paintings, the two women were close. Writer Ruth Andrew Ellenson states that O'Keeffe and Stettheimer "played off each other in an artistic dialogue that pushed both women creatively." "Stettheimer's Family Portrait II," for example, she adds, "is a response to O'Keeffe's Manhattan, both exploring the imagery of modernity in a changing New York."

In 1916, Stettheimer's paintings were exhibited in a solo show at M. Knoedler & Co. Gallery in Manhattan. For this exhibition, she decorated the gallery with sets of furniture and ornate curtains that she'd designed. Her vision of combining art with design elements to create a total aesthetic environment predated the concept of Installation art. The Knoedler Gallery show was both her first and last solo exhibition during her lifetime, however. After some mixed reviews and without any work sold, Stettheimer retreated from public exhibitions, only occasionally contributing her paintings to group shows. Despite a lukewarm reception from critics and collectors, she was very well admired by her artistic peers. O'Keeffe even pleaded with Stettheimer to keep pursuing a career in painting in a letter, writing, "I wish you would become ordinary like the rest of us and show your paintings this year!" Alfred Stieglitz also tried to get Stettheimer to exhibit her work to the public. He repeatedly offered to display her work at The Intimate Gallery, a successful venue which he opened in 1925, but she turned him down. She eschewed the mainstream art scene and business in favor of more intimate gatherings and cultural happenings.

Although she chose not to participate as a professional artist, Stettheimer made significant contributions to New York's cultural scene, especially in theater. Her talent for theatrical design was exemplified through the sets and costumes she created for the inaugural production of author and modern art collector Gertrude Stein and composer Virgil Thomson's opera, Four Saints in Three Acts. The show opened on Broadway in 1934. Her billowing, intricate costumes were made with vibrant lace, silk, feathers, sequins, and taffeta. Reflecting her vision for a three-dimensional aesthetic space, her design process was unconventional, hands-on: "Sketching was not her medium of choice," explains design writer Molly Long, "instead, she designed intricate miniature figurines of each operatic character, and scaled-down shoebox stages for every scene of the show."

Later Years and Death

Stettheimer's best-known group of works are her Cathedrals paintings. These are large canvases that depict what she considered to be New York City's most iconic places: Broadway, Wall Street, Fifth Avenue, the Museum of Modern Art, the Metropolitan Museum of Art, and the Whitney Museum of American Art. Although she used the term "cathedral" in each painting's title, these works of art portray secular scenes. Art historian H. Alexander Rich wrote that "the series is designed to resemble a multi-part altarpiece, not merely in terms of its scale and dimension (each work measures more than 50 inches wide and 60 inches high) but also in its ideal display."

She spent her later years finalizing her Cathedrals and working for theatrical projects. She worked on her art until her death from cancer on May 11, 1944 at the age of seventy-two. Her last request was that her works not be sold, but rather donated to various museums across the United States. Her sister Ettie, lawyer Joseph Solomon, and friends obliged.

In 1946, Marcel Duchamp curated a large, posthumous retrospective of her work at the Museum of Modern Art. Friend and critic Henry McBride wrote the accompanying exhibition catalog. In 1949, Ettie published a book of her sister's poetry titled, Crystal Flowers.

The Legacy of Florine Stettheimer

Stettheimer eschewed labels for her work, and it is difficult to contextualize her within any preexisting modernist canons. Such a difficulty, however, renders her work and legacy all the more important as a tool for re-thinking the canons themselves. As art critic Max Pearl reflects, "Because [her work] isn't easily lumped in with the era's major movements, it was written off as lovely but ultimately unclassifiable and therefore a blip in art history."

When we look closely, however, all along, there had been an undercurrent of appreciation among artists who would later shift the course of post-World War II art. As art critic Peter Schjeldahl writes, "She seemed an eccentric outlier to American modernism, and appreciations of her often run to the camp." That appreciation would have a significant impact on the development of postmodernist movements like Pop Art. Andy Warhol once remarked that she was his favorite artist. As a burgeoning queer artist in the aftermath of the macho bravado of the Abstract Expressionists, Warhol likely saw in Stettheimer a precedent for an alternative aesthetic that embraced other expressions of gender. As Somerville notes, "Her singular feminine, theatrical, figurative style fell out of fashion when first Abstract Expressionism and then Minimalism dominated the art world." But artists such as Robert Rauschenberg and Warhol saw in her a seamless blending of avant-garde compositional ideas with popular imagery and everyday life, the latter of which became hugely important for them and their followers.

Contemporary critics have also cited her as a proto-feminist artist. As art writer Alexxa Gotthardt writes, her paintings contain a "a celebration of womanhood - and female autonomy - that today reads as brazenly feminist." With a feminist insight into the question of gender division and labor, we can also appreciate Stettheimer's role as a saloniste. While traditional art history has been predicated on the achievements of singular artists, a broader understanding of creative labor would also include consideration of the social organizing and community building role that created a wider ecology of collaboration and exchange in which artists could thrive.

Althought her work went unappreciated by the mainstream art world of her time, those who knew her always understood the significance of her cultural contribution. Carl Van Vetchen aptly sums up her legacy in a 1947 piece for Harper's Bazaar, asserting that she "was both the historian and the critic of her period and she goes a long way toward telling us how some of New York lived in those strange years after the First World War, telling us in brilliant colors and assured designs, telling us in painting that has few rivals in her day or ours."

Influences and Connections

Ask The Art Story AI

Ask The Art Story AI