Summary of Paul Strand

The history of modern art shows that America offered a fertile environment for some of the most important photographic pioneers of the twentieth century. It was perhaps Paul Strand who carved out a most unique position amongst them. Strand is often discussed as the architect of the so-called Straight Photography; a pure photographic style that utilized large format cameras to record, and bring new perspectives to ordinary or previously ignored subjects in the name of fine art. Strand's 'Straight' aesthetic proved so persuasive in fact that it was adopted by other luminaries in the photographic circle and the 'Straight' ideal formed part of the clarion call for the famous f/64 Group who shared similar ideals with Strand, as did a number of other Straight photographers in the next several decades. Yet Strand was to push forward by extending the 'Straight' aesthetic to the field of documentary and he became highly regarded, and something of a standard-bearer, for those in pursuit of social and political redress through both the still and moving image.

Accomplishments

- Strand had come to the view that photographic art should amount to more than 'false' figurative pictures set in idealized settings; this practice, known as Pictorialism, was reviled by modernists. He recognized that the camera held a patent advantage over other plastic arts in that it could freeze a moment in time and space in a way that was impossible to replicate by hand or in real time. His Straight Photography offered then the most unadulterated route to a purer, deeper photographic experience.

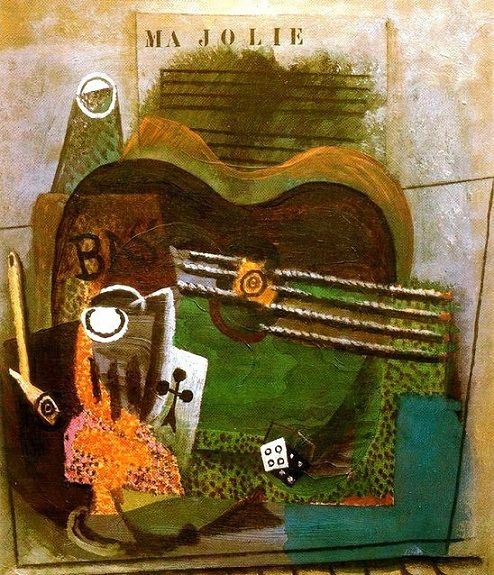

- Taking inspiration from the formalist, or cubist, paintings of Cézanne, Braque, and Picasso, Strand became fixated on the idea that the photographic image could also be broken up compositionally. Straight Photography used large format cameras to create high contrasts (over shading), flat (or two dimensional) images, semi-abstractions and/or geometric repetitions. The images were reliant on size and context for their full affect and were thus often intended to be hung on the hallowed white walls of dedicated photographic galleries.

- Unlike others in his artistic circle who were fully invested in the 'art-for-art's-sake' doctrine, Strand's worldview accommodated the idea that art should be able to engage the spectator spiritually and socially. He is thus associated with the idea that high art can (should indeed) accommodate abstraction and realism simultaneously; that is - in the same photograph or the same documentary film.

Important Art by Paul Strand

Wall Street

Wall Street is an historically significant image, both for Strand and for the development of photographic art. It marked a clear departure from a style of soft-focused Pictorialism (practiced hitherto by Strand) whereby the photographer used a camera and dark-room manipulation to produce images that mimicked that rather unfashionable (by modernism's standards) painting style. The image provides an early example of Strand's willingness to accommodate documentary realism and abstraction within the same frame. On the one hand, Strand offers the spectator an objective, 'straight', record of a street scene showing walking pedestrians as the sun elongates their shadows; on the other, we have a high contrast interplay of light and dark as the shadows formed by the niches of the large Morgan Trust Bank building produce a slanting geometric pattern.

Unlike his contemporaries, such as Alvin Langdon Coburn and Karl Struss who emphasized activity and movement in their urban images, Strand's approach was more deliberate and as such he typically focused his images on slower movements and static scenes. Indeed, with Wall Street in particular, Strand was shocked that he was able to get such a sharp image of the moving people considering how slow the plates took to process. It is said that Edward Hopper became fascinated with this image, and adopted some of the same formal techniques for his own paintings.

Platinum palladium print

Porch Shadows

During the summer of 1916, Strand vacationed at a rented cottage in Twin Lakes, Connecticut. Inspired by the European avant-gardes, and the Cubists especially, he had already reached the conclusion that "All good art is abstract in its structure" and he began to explore the question, posed by the European painters, of "what a picture consists of, how shapes are related to each other, [and] how spaces are filled". Using everyday items, including kitchen furniture and crockery, and fruit, Strand used his large plate camera to transform - or elevate - the mundane utilities into pure two-dimensional patterns. The resulting collection did in fact include some of the very first purely abstracted photographic images. Porch Shadows exemplifies this way of working. On close inspection, we might deduce that the object in question is no more than an ordinary round table placed on a terrace porch. But Strand alters our perception by firstly rotating the image. The geometric shapes meanwhile - thin stripes, parallelograms and a large triangle - are created in the shadows and light brought to the composition by the strong sun as it penetrates the slats of the terrace window.

Silver-platinum print

Blind Woman, New York

Strand believed that the furtive nature of authentic urban portraiture was both vital and morally justifiable: "I was attempting to give something to the world and not exploit anyone in the process" he said. This early portrait, first published in Camera Work, was taken in Five Points, the heart of the immigrant slums on the Lower East Side of Manhattan and is indicative of Strand's socialist and artistic mission. It shows a desolate woman in medium close shot. Around her neck hangs a hand-painted sign that alerts us to the fact that she is "BLIND", and above which, a numbered badge pinned to her black smock identifies her as a licensed newspaper vendor. Her attention is drawn to an event outside the frame, and though she is blind, the photograph confirms that she is oblivious to the camera's close proximity. Indeed, in order to achieve portraits of such arresting quality Strand devised a strategy whereby he rigged his camera with a false lens that pointed forward, while the working lens was actually placed at a ninety-degree angle and hidden from the subject's view under his arm.

In his influential book The Ongoing Moment in which he looked at photographic trends, Geoff Dyer suggested that the blind women's off-centre pupils reflected Strand's own skewed lens set up and that, moreover, the blind subject was more generally "the objective corollary of the photographer's [own] longed-for invisibility". In any case, practical and moral complications notwithstanding, Strand maintained that the task of portraiture was to "almost bring the presence of that person photographed to other people" and that, though the 'ordinary' subject has been all but anonymous till now, the spectator is "confronted with a human being that they won't forget". This photograph "immediately became an icon of the new American photography, which integrated the humanism of social documentation with the boldly simplified forms of modernism" according to New York's Metropolitan Museum of Art.

Platinum Print

Percé Beach, Gaspé, Québec

In 1929, Strand took a trip to Canada with his wife, Rebecca Salsbury. While there, he produced this landscape. Though Percé Beach meets the principal criteria for a landscape, we can find aesthetic correspondences here with his more iconic Wall Street photograph (produced 12 years earlier). In this photograph, rather than a building, a large body of water dominates the frame; it is the cliffs, that enter from the left side of the frame, that this time cast their shadows over a body of sea (rather than pavements).

In a statement that seems at first a little incongruous, Strand spoke of color in his photography. He was of course shooting in black and white, but it was his practice to use papers with color tint (while bemoaning the fact that "everytime I find a film or paper that I like, they discontinue it") that imitated the atmosphere of the location at which he was shooting. In this case Strand used paper with the cold blue tones that had matched his experience on the Percé Beach shoot. In keeping with his fascination of 'how spaces are filled', moreover, Strand was of a mind that a balance of weight and air in the photograph was the most important compositional factor. The weight is created by dark tones in rocks, rooves and boats; the idea of air being expressed by the light in the sky and as it is reflected on the surface of the sea. When one looks for evidence of Strand's commitment to represent the lives of ordinary people, meanwhile, we find a workers' narrative in the bottom foreground of the frame. We see small figures, this time 'dwarfed' by the forces of nature (rather than man-made architecture), grappling with a large fishing boat. It is unclear if the fishermen are about to set sail, or if they are preparing to moor their vessel, but the spectator is left in little doubt of its importance to their lives and livelihoods.

Silver Gelatin Print

Native Land

Through Native Land Strand wanted to expose civil liberties violations in America during the 1930s. The film focused specifically on the bill of rights which had come under attack from corporations who, amongst other things, used spies and contractors to undermine and dismantle labor unions. The film, both 'a call to action' for workers and a timely reminder to them of their constitutional rights, was co-directed by Strand and Leo Hurwitz (a signed-up, and later blacklisted, member of the Communist Party), and featured a narration by prominent African-American singer, actor, and activist Paul Robeson.

Best described as a 'semi-documentary' (or 'docu-drama') Native Land integrates newsreel footage (including scenes from the so-called Memorial Day massacre of 1937 in which Chicago police killed ten striking protesters) with a fictional narrative (a story about the subjugation and murder of sharecroppers whose union has been secretly infiltrated). In keeping with the artistic and ideological traits of Strand's worldview, moreover, Native Land sought to challenge the classical Hollywood narrative by taking the ordinary American laborer and turning him from subordinate or comedy figure into the plot-carrying hero. At the time of the film's release, the influential New York Times film critic Bosley Crowther hailed Native Land as "one of the most powerful and disturbing documentary films ever made". However, the unfortunate timing of the film's release, shortly after the attack on Pearl Harbour, meant that the country was seeking unity and had little appetite for socio-political self-examination.

Film

The Lusetti Family, Luzzara, Italy

The Lusetti Family represents Strand's late period (after he had resettled in Europe) and features in his book Un Paese, Portrait of an Italian Village, which was published in 1955. The photograph marks an interesting divergence from his American portraiture (such as Blind Woman, New York) inasmuch as his subjects now posed for Strand's camera. Strand had accepted an invitation from the Neorealist screenwriter Cesare Zavattini to visit the Italian's agricultural hometown of Luzzara, in the northern Po River Valley. Once received into the Luzzara community (Strand stood in the central town square every day until they became used to his presence) he spent two months photographing the village - once a stronghold for anti-fascist resistance - and its inhabitants. One of his sitters, a young farmer's daughter named Angela Secchi, later spoke of her experience: "He [Strand] grabbed a large hat off my uncle's head and put it onto mine, he then took my uncle's scarf and an old, rumpled smock and told me to wear it on top of my dress. He wanted me to look like a poor country girl". This manufactured tourist's view of village life jarred somewhat with Strand's 'Straight' aesthetic.

It was then incumbent on Zavattini to provide prose that would give Strand's images their socio-political bent. The Lusetti family portrait is comprised of a mother and five of her eight sons; all of them WWII veterans. Their blank, pained expressions do indeed hint at some collective trauma. However, the image only takes on tangible meaning once we learn that four of the mother's children had died in infancy, while her husband, the boys' father, a local communist partisan, had been clubbed and beaten by Fascist assailants on two occasions before being killed in active service. An unwanted irony of the project was that only one thousand copies of the book were produced and at a premium ("People were amazed because the book cost the same as a bicycle" Secchi said later) that put them beyond the meagre budgets of the villagers.

Gelatin Silver Print

Anna Attinga Frafra, Accra, Ghana

For the last of his geographical series, Strand visited Ghana where, with the cooperation of then President Kwame Nkrumah (deposed two years later), he spent three months between 1963 and 1964 photographing the country and its people. However, the book, Ghana: An African Portrait, featuring a companion text by the Africanist scholar Basil Davidson, was not published until 1976 (four years after the death of Nkrumah). According to the African Studies scholar Zachary Rosen, the aim of Strand's project was to reveal Ghana as "a new African nation of peoples poised for industrial ascension" though Strand was able to show his respect for Ghana's heritage simultaneously via a series of juxtapositions in which the images of technological and economic advancement sat beside images in, and of, more traditional and natural environments. It was Strand's belief that the job of the documentarian was to describe the lives of ordinary people. He declared: "The People I photograph are very honorable members of this family of man and my concept of a portrait is the image of somebody looking at it as someone they come to know as fellow human beings with all the attributes and potentialities one can expect from all over the world". One can see this humanist philosophy in practice in his portrait of the young student, Anna Attinga Frafra. Wearing a white sleeveless shirt, she is positioned in front of a plain white wall. Plant fronds intrude from the left side of the frame but the spectator's eye is drawn to the detail of the three textbooks she is carrying on her head. When Rosen argued that Strand had managed to avoid the trap of producing "patronizing anthropological photographs" he might well have had an image like this in mind; one that captures the personality of a subject who came to symbolize a progressive thinking and independent African state.

Gelatin silver print

Biography of Paul Strand

Childhood

Nathaniel Paul Stransky was born in New York to German-Jewish parents in 1890. Father Jacob Stransky presented his son with his first camera when he was just twelve years old, though his son's interest in photography wasn't to blossom until he had left high school in 1907. Upon graduation Strand joined his father's enamelware import business but he used his spare time to attend a photographic club at the Ethical Culture School run by renowned social documentarian Lewis Hine. Strand decided on his future following a club field trip to Alfred Stieglitz and Edward Steichen's 291 Gallery. Inspired by the visit, Strand was emboldened to seek feedback on his own work from the older Stieglitz who encouraged Strand with "very great criticism" from which he "learned an enormous amount". That visit, along with the influence of Hine's socialist outlook, represented a pivotal moment for Strand who, aged 17, declared his intention to become "an artist in photography".

Education and Early Training

Strand and his first wife Rebecca Salsbury (they were married in 1922) were often seen with Stieglitz and his wife Georgia O'Keeffe. Strand had in fact exchanged several romantic letters with O'Keeffe before she married Stieglitz and the two couples became close friends. By the late 1920s however complications in their personal relationship surfaced following romantic trysts involving Salsbury and both Stieglitz and O'Keeffe. Strand's professional relationship with Stieglitz dated back however to 1915 when Strand's soft-focus pictorialism drew stinging criticism from Stieglitz, the ardent modernist. Strand realized that if he was to be taken seriously as "an artist in photography" he would have to develop a signature technique of his own. He acknowledged as much in the following quotation: "You may see and be affected by other people's ways, you may even use them to find your own, but you will have eventually to free yourself of them. That is what Nietzsche meant when he said, 'I have just read Schopenhauer, now I have to get rid of him'". Indeed, as a direct result of Stieglitz's earlier criticism - not to mention his undoubted aesthetic influence - Strand spent two years developing the style that was to become known as Straight Photography. It seems it took Strand rather longer to refine his art however. Responding later in his career to the view put by fellow photographer Minor White that it took twenty years to become a photographer, Strand suggested that that might be "a bit of an exaggeration" and that becoming a professional photographer really "does not take any longer than [the eight or nine years] it takes to learn to play the piano or the violin". Strand quipped "If it takes twenty years [then] you might as well forget about it!".

Strand declared that the "measure of [an artist's] talent - of his genius, if you will - is the richness he finds in such a life's voyage of discovery and the effectiveness with which he is able to embody it through his chosen medium". It was a measure of his own talent then that he became revered as a figure who had set out some of the very provisos on which modernist photography would be defined. Stieglitz had in fact been so impressed with Strand's artistic maturation that he adopted the Straight Photography aesthetic for his own work. Strand knew he had 'arrived' when, in 1917, Stieglitz gave him a major exhibition of his own at the 291 Gallery and then allotted the last two issues of his photography magazine Camera Work entirely to Strand's work. Writing around the same time, Strand published an article entitled 'Photography and the New God' in which he summed-up the 'Straight' philosophy as follows: "[through its] pure and intelligent use [the camera can] become an instrument of a new kind of vision, of untouched possibilities, related to but not in any way encroaching upon painting or the other plastic arts".

Mature Period

On the back of his role as medical cinematographer, Strand was inspired in 1921 to collaborate with the painter and commercial photographer Charles Sheeler on a short, silent film called Manhatta (AKA: New York the Magnificent). The film, which documented the bustle of every day street life under the architectural shadows of the looming New York skyline, reflected Strand's aesthetic preoccupations and is considered by some to be the first American avant-garde film. It was a little later however that Strand's approach became more transparently political. He made Redes (The Wave) in 1934 (documenting the economic problems faced by a Mexican fishing community), and, with the American filmmaker Pare Lorentz, The Plough that Broke the Plains in 1935 (a film that addressed the Dust Bowl situation facing the Great Plains region of the United States and Canada following a period of uncontrolled agricultural farming). Soon after, in 1936, Strand joined with American photographer Berenice Abbott to set up the Photo League, a group of photographers committed to the aim of raising social awareness of trade union activities and civil rights protests. Four years later, Strand co-directed with Leo Hurwitz, Native Land, a civil-liberties themed 'docudrama', narrated by the prominent African-American singer, actor, and activist Paul Robeson. Native Land was in fact produced under the auspices of Frontier Films, a pro-labor, anti-fascist, collective, formed by Strand in the late 1930s.

Late Period

Strand acknowledged that "life is so complex" that the artist is presented with "all sorts of possibilities". That being the case, he maintained that the said artist should be able to avoid doing "the same thing over and over again" (albeit that that was "one of the dangers that all artists face"). Based on that conviction, the late period in Strand's career brought a new dimension to his oeuvre. His photography, while still produced according to the codes of his 'Straight' aesthetic, relied on prose and/or poetry to give them a fuller meaning. The new tone was set in 1950 with the publication of Time in New England. The book was edited by the American photography critic Nancy Newhall who had matched Strand's images with an anthology of New England writings dating from the 17th century to the present day. In the same year, Strand moved to Orgeval in France where he settled with his third wife, Hazel Kingsbury (having been married to his second wife, Virginia Stevens, between 1935 and 1949). Between his arrival in Orgeval, and up to his death in 1976 (he had never made the effort to learn to speak French), Strand embarked on a series of overseas projects. His visits to Italy, Egypt, Morocco, Romania, the Outer Hebrides and Ghana gave rise to a series of photo-geographic books featuring people, landscapes and text. He collaborated, for instance, with Claude Roy on La France de profil (1952); for Un Paese (1955) with the Italian neorealist screenwriter Cesare Zavattini (Bicycle Thieves); and for Ghana: An African Portrait (shot in the early 1960s but not published until 1976, the year of his death) Strand's images were enriched by the words of the Africanist scholar Basil Davidson.

The Legacy of Paul Strand

In 1984 Strand was inducted into the International Photography Hall of Fame (IPHF) on the endorsement that he had photographed the everyday world "with precision and truth". Whether or not one chooses to eulogize Strand as the sole architect of Straight Photography, there can be no doubt that his photography helped cultivate the idea that it was only the camera that could show the world in such detail - only a machine could represent the world with such clarity and with such purity - and that, in the right hands, photography could hold its own within the bigger modernist program.

Writing in his book The Photograph, the scholar Graham Clarke expressed the opinion that Strand should be placed in a group including Stieglitz and the other 'Straight' adherents associated with the f/64 Group: namely László Moholy-Nagy, Manuel Alvarez Bravo, Berenice Abbott, Walker Evans, Robert Capa, Ansel Adams and Edward Weston. According to Clarke, this select cadre of photographers helped promote the impression of the modern photographer as an 'inspired philosopher who transforms a dull literal reality into something new and ideal'.

What distinguished Strand from his peers, however, was his attempts to combine the philosophical elements of Straight Photography with a strong socio-realist plan. Indeed, Strand himself baulked at the romantic vision of the modern artist as virtuosic genius. He said as much in his 1946 obituary for Stieglitz when he spoke, not as a single artist, but rather as part of a collective including fellow activists Abbott, Zavattini, British historian Basil Davidson, American film director Joseph Losey and Scottish poet Hugh MacDiarmid. His legacy might be best summed up then by Strand himself when he wrote: "We realize as perhaps he [Stieglitz] did not, that the freedom of the artist to create and give the fruits of his work to people, is indissolubly bound up with the fight for the political and economic freedom of society as a whole".

Influences and Connections

-

![Edward Weston]() Edward Weston

Edward Weston -

![Pablo Picasso]() Pablo Picasso

Pablo Picasso -

![Georges Braque]() Georges Braque

Georges Braque ![Lewis Hine]() Lewis Hine

Lewis Hine

Useful Resources on Paul Strand

- Paul Strand: Master of Modern PhotographyBy Peter Barberie, Amanda Bock, Martin Barnes, Karen Beckman, Tsitsi Jaji, Maria Antonella Pelizzari, Samantha Gainsburg

- Paul Strand: Essays on His Life and WorkBy Maren Stang and Alan Trachtenberg

- Paul Strand: The World On My DoorstepBy Ute Eskildsen and Catherine Duncan

- Paul Strand in MexicoBy James Krippner and Alfonso Morales Carrillo

- The Photograph (Oxford University Press, 1997)By Graham Clarke

- The Ongoing Moment, A Book About Photographs (Edinburgh, Canongate, 2005)By Geoff Dyer

- Paul Strand: Aperture Masters of PhotographyBy Peter Barberie

- Paul Strand: The Garden at OrgevalBy Joel Meyerowitz

- Paul Strand: SouthwestBy Trudy Wilner Stack and Rebecca Busselle

- Tir a'Mhurain: Outer HebridesBy Basil Davidson and Catherine Duncan

- Un Paese: Portrait of an Italian VillageBy Cesare Zavattini

- The Photograph (Oxford University Press, 1997)By Graham Clarke

Ask The Art Story AI

Ask The Art Story AI