Summary of Gilbert Stuart

Stuart was one of America's first great portraitists. He holds the distinction of painting the new republic's first six presidents, as well as many other important public figures of the day, including first ladies, statesmen, and merchants. Stuart's refined portraits have shaped the way that Americans have come to visualize many of its nation's Founding Fathers. Having established his credentials for relaxed yet reverential portraiture in London and Dublin, he returned to his country of birth where he showed his business acumen by establishing successful practices in New York, Philadelphia, Washington, D.C., and Boston. Stuart's most iconic portrait, the famous Athenaeum Portrait, remains the definitive image of America's first president, George Washington.

Accomplishments

- With Benjamin West, John Singleton Copley, and John Trumbull, Stuart ranks as one of the preeminent American artists of the late-eighteenth century. Having trained in London in the idealized Neoclassical style, he captured his sitters' character and status through carefully considered choices in posture, costume, color, and setting. He is also credited with introducing to America the subtle shading techniques (bringing greater detail and illusion of depth) preferred by many of London's leading Grand Manner artists.

- Of his 1,000 + portraits, Stuart's unfinished Athenaeum Portrait is his great gift to American culture and history. He painted (and repainted) several images of George Washington, but the Athenaeum bust is the most iconic having been the source for the engraving of America's first president that has taken pride of place on the one-dollar bill since 1869.

- Stuart is best known for his portraits of powerful male sitters (including six presidents) but he was also celebrated for his ability to capture the strength and influence of his many female subjects. His portrait of Dolley Payne Todd Madison (1803-05), for example, became the definitive record of the future First Lady's beauty, charm, and strong sense of fashion. Stuart's portrait of Dolley went some way in confirming an image of what it was to be a modern American woman.

- Stuart skill as a painter elevated the status of portraiture in America. But he was not just an artistic pioneer, Stuart was also instrumental in establishing the "business of portraiture" in America. Through his various practices in the major cities in eastern America, he fostered the attitude that portrait painting was a laudable profession and that it was a privilege for clients to sit for a professional painter.

The Life of Gilbert Stuart

According to historian and acquaintance of the artist, William Dunlap, Stuart, "left us the features of those who have achieved immorality for themselves, and made known others who would but for his art have slept in their merited obscurity".

Important Art by Gilbert Stuart

Gilbert Stuart Self-portrait at 24

Stuart painted this self-portrait in the early stages of his career. There is an intensity to the stare of the artist as he looks out at the viewer over his right shoulder. Wearing a black coat, and jacket and painted against a dark brown background, the contrast in colors with that of his creamy complexion give his face a glow which brings a palpable sense of drama to the work.

There is a personal story associated with this painting that was shared years later by the artist himself. He explained that while still struggling as an artist in London, he saw a portrait for sale by the English artist William Dobson. Despite living in near poverty, Stuart borrowed the money to purchase the painting with which he had become completely enamored. Once in his possession, Stuart showed the painting to his mentor, the American artist Benjamin West, who also greatly admired the work. Stuart told West he would gift him Dobson's painting if and when West told him that he had painted a portrait as good as Dobson's (it is not known if he was true to his promise).

Dobson's influence is clear in the pose and manner in which Stuart rendered his own image. Professor Dorinda Evans cites a comment from a journalist on seeing the painting when exhibited in 1828, "[Stuart] is represented as looking in a mirror, intently copying his own face. He painted it in London for Dr. Waterhouse [Stuart's good friend], and it was greatly admired by Mr. West [...]. The mouth is relaxed, making it a picture of intense attention in copying his own features and mind. He intentionally gave the whole, in the colouring, and in the indistinct marks of the Rubens-hat, shirt collar, and hair, the cast of an old picture".

Oil on canvas - Redwood Library and Athenaeum, Newport, Rhode Island

The Skater (William Grant)

Here Stuart depicts William Grant, a thirty-two-year-old London barrister, gliding across a frozen pond with his left foot outstretched in front of him as his right leg propels himself forward across the ice. Appropriately dressed in a long woolen coat and hat, his arms are crossed in front of him, and his head is turned to look over his left shoulder. Solitary in his pose, a group of skaters are gathered together in the distance and others are positioned on the bank of the ice.

This portrait was something of a landmark work for Stuart. The National Gallery of Art states that it was "Stuart's first effort at full-length portraiture [and] its originality brought the artist so much notice at the 1782 Royal Academy exhibition that he soon set up his own studio". The Skater, which marked the end of his five-year apprenticeship under Benjamin West, effectively launched Stuart's professional career.

Inspired by a day spent skating together, this work demonstrates Stuart's characteristic habit of encouraging a sense of relaxed comradery with his sitters. The result was a unique type of portrait for a country steeped in the formal traditions of the classical Grand Manner painting (as exemplified by the works of Sir Joshua Reynolds and Thomas Gainsborough). According to curator Carrie Rebora Barratt, "the story that Stuart turned his client's small talk about the weather into an idea for the picture belies the artistic brilliance of the conception for it was a shockingly modern picture of a gentleman in motion. A reviewer wrote, 'One would have thought that almost every attitude of a single figure had long been exhausted in this land of portrait painting, but one is now exhibited which...produces the most powerful effect.' Such a response would have been just what Stuart wanted: a reaction to his picture strong enough to attract attention".

Oil on canvas - National Gallery of Art, Washington, D.C.

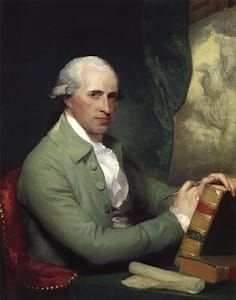

Joseph Brant

Joseph Brant, whose given name was Thayendanegea, was the paramount war chief of the Iroquois Nation, and the face of Native America in Europe. This portrait was commissioned by Hugh (Earl) Percy, his English ally and "brother in arms" in Boston and New York during the American Revolution. As curator Carrie Rebora Barratt describes, "Stuart gave Brant a fully modeled visage projecting the strong characterization for which he had become so well known. The limpid eyes, strong nose, resolute mouth, and slightly flaccid jawline describe a man of intelligent determination capable of conciliatory debate. The clothing maintains his nationality and his dignity [...]. A black shawl with silver-thread fringe covers his left shoulder and arm, and on his head, with dark hair pulled back in a queue, is a close-fitting black and red cap embellished with [...]silver rings and with a tuft of yellow, orange, and black feathers fixed to the band. The silver ornamentation conveys his high rank....".

Brant travelled to London twice (in 1775 and 1785) on behalf of the Iroquois, seeking protection for his people from the British government. On the second visit, Brant negotiated land claims with the British Crown and obtained the King's pledge of protection. Stuart was commissioned to mark the occasion with this portrait, and in it, he shows Brant wearing the gorget (neck ornament displaying military rank) gifted by King George III as a symbol of their close relationship. Sotheby's auction house writes that, "The reputation and fame [Brant] had acquired during the war meant that he was held in high esteem by the British aristocracy, and he used the opportunity [of his second visit to London] to reacquaint himself with many of the British officers with whom he had served in North America. [...] Brant 'presented a seductive public image that merged diplomat and warrior, gentleman and brute', astutely adapting Iroquois custom and dress to suit the occasion". His visit also gave Brant the opportunity to meet up with his old comrade, Percy, who had commissioned Stuart to paint his esteemed visitor's portrait. Stuart was also commissioned to paint a second Brant portrait by Francis Rawdon-Hastings, 1st Marquess of Hastings (who had also fought in North America during the Revolution).

Oil on canvas - Private Collection

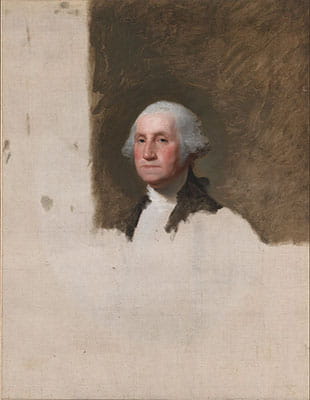

George Washington (The Athenaeum Portrait)

This canvas features a bust of the Statesman painted against a brown background while the lower half and left side of the canvas remains unfinished. The portrait was commissioned by Washington's wife, Martha, who was greatly impressed with the first painting Stuart had made of her husband. According to the National Portrait Gallery, "that painting was so successful that according to artist Rembrandt Peale, Martha Washington 'wished a Portrait for herself.' She persuaded her husband to sit again for Stuart 'on the express condition that when finished it should be hers. Stuart, however, did not want to part with the picture and left it unfinished so that he could refer to it when producing future commissions [and perhaps as justification for not giving it back his client]. Known as the 'Athenaeum' portrait because it went to the Boston Athenaeum after Stuart's death". A matching portrait, also unfinished, of Martha also stayed in Stuart's possession until his death.

Historian Areeba Ahmed writes, "Stuart's contemporaries considered the Athenaeum portrait as the peak of his work, as did Washington's own step-grandson, George Washington Parke Curtis in part because the overall expression and the classical style portrays Washington as a moral ideal, exuding power and authority. The portrait's incomplete state is perhaps another factor contributing to its distinction as it seems to bring focus to Washington's head with the unfinished background providing it more dimension and realism. These factors were fitting for a man so idolized as Washington, and Stuart made the most of the image's wide appeal by painting and selling many replicas of it".

Stuart used the Athenaeum Portrait as his starting point for a full-body portrait of Washington known as the Lansdowne Portrait (after the Marquis of Lansdowne, William Petty, and the Philadelphia socialite Anne Willing Bingham who commissioned it). Painted in the same year, the Lansdowne Portrait carries a Baroque and Neoclassical grandeur befitting of a leader of state, and is believed to allude to the pose Washington adopted at his presidential address to Congress in December 1795. The Lansdowne Portrait was quickly recognized as the best pictorial summation of Washington's presidential role and led to many commissions for replicas (while also giving rise to many pirate copies). But it is the Athenaeum Portrait, an engraving of which was first printed on the one-dollar bill in 1869, that is considered the "definitive Washington". It is undoubtedly Stuart's most famous portrait, with its iconic status further confirmed in 1932 when millions of prints were distributed to American classrooms as part of the bicentennial celebration of Washington's birth.

Oil on canvas - National Portrait Gallery, Washington, D.C.

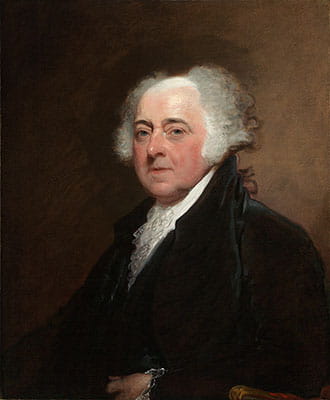

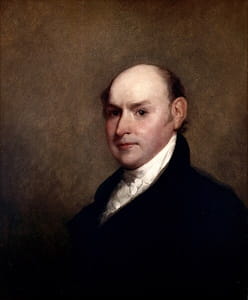

John Adams

Stuart's portrait of John Adams features the second President of the United States from the waist up wearing a formal black jacket and white shirt. Looking out at the viewer over his left shoulder, his stare, while intense, is not stern. It formed part of a pair of portraits, the other featuring Adams' wife, Abigail Smith Adams. Curator Ellen G. Miles calls these portraits, "the most memorable pendant portraits of these forceful personalities". This painting alludes to the uneasy relationship between the artist and sitter, with John Adams remarking at one point, "Mr. Stuart thinks it the prerogative of genius to disdain the performance of his engagements". Stuart was a legendary procrastinator who was sometimes given to take years to finish commissions, or worse still, to never complete them at all. Indeed, the portrait(s) was begun in 1800 but took Stuart fifteen years to complete.

The Columbus Dispatch (reporting on the restoration of a number of Stuart portraits at Washington's, National Gallery of Art) writes that, "Abigail Adams grew impatient with Stuart, admonishing him in letters to complete their commissioned paintings. He had apparently moved on to other works and was in high demand. 'I just don't know what to make of this Mr. Stuart,' she said at one point [...] She persisted, though, to have the paintings completed because the Adams family apparently thought Stuart's skill in capturing the essence of personality was unmatched". In fact, the Adams portrait(s) was only completed after years of demands, the last of which came via the Adams' son, and future President, John Quincy Adams (who may have wanted the painting at this point more than his own father who had given up hope of ever seeing the finished work). The majority of the painting was completed in 1815 with Abigail Adams informing her son, "Your father has gone [...] to sit to Stuart for his portrait - if he gets a good likeness, as I think it promises, you will value it more than if it had been taken in youth or Middle Age".

Oil on canvas - National Gallery of Art, Washington, D.C.

Dolley Payne Todd Madison

While Stuart is best remembered for his portraits of male subjects, his ability to beautifully represent his female sitters is clear in works such as his portrait of Dolley Payne Todd Madison. The Office of the Curator and The White House writes, "This handsome portrait was painted by the celebrated artist, Gilbert Stuart, during his stay in Washington, 1803-1805. The great demand for the artist during this visit prompted a friend of Dolley Madison's to report that 'Stuart is all the rage. He is almost worked to death, and everyone afraid they will be the last to be finished'".

Stuart painted Dolley's portrait, with another of her new husband, and current secretary of state, James Madison, before they became respectively President and First Lady (in 1809). Once married, Dolley became a formidable hostess and a powerfully independent First Lady. Her legendary weekly gatherings, what became known as "squeezes", were politically neutral space and welcoming of all comers. The National Gallery says of Dolley, "She was beautiful, charming, and fashionable, and the perfect counterpoint to her husband's subdued personality".

Describing Dolley's painting, curator Ellen G. Miles states, "Mrs. Madison wears a high-waisted white dress with a low-cut bodice, a French style then in fashion; the dress is trimmed with gold ribbon, and she wears a three-strand gold necklace. Her hair is arranged in the popular neoclassical style, pulled back in a chignon with loose ringlets framing the face. In the background are a red curtain and a column, with a cloudy blue sky beyond". The Montpelier Foundation adds that by mixing "the high-waisted, low-cut dresses of the period [...] Dolley was making conscious material decisions to communicate powerful ideas; she was personally helping to define the public image of American womanhood".

Oil on canvas - The White House, Washington, D.C.

Thomas Jefferson (The Medallion Portrait)

Striking in its simplicity, Stuart's portrait of Thomas Jefferson, third president of the USA, and the author of the Declaration of Independence, features only a profile bust rendered in shades of brown. Known as the Medallion Portrait it takes its name from the medal or "coin like" look of the work which is enhanced by the circular base on which it was rendered. The Jefferson Museum at Monticello states that, "Jefferson called on Stuart in his studio in Washington on June 7, 1805, for he noted in his memorandum book that he then paid Stuart one hundred dollars for his portrait. After he sat for the second [the so-called Edgehill portrait] Jefferson persuaded Stuart to sketch him in the medallion form, which he did on paper with Crayons. [Jefferson remarked that although] 'a slight thing I gave him another 100.D. [$100] probably the treble of what he would have asked. This [portrait] I have; it is a very fine thing [although] very perishable'. On June 18 he thanked Stuart for 'taking the head a la antique.'".

Of particular interest here is Jefferson's hairstyle. According to curator Ellen G. Miles, "the portrait shows Jefferson with a short haircut of the type fashionable in France. While the older fashion, in which a man's hair was pulled back and tied in a queue, had political associations with the Federalists, the short haircut became a political gesture that was distinctly pro-Jefferson, a neoclassical style with antecedents found on Roman coins and in Roman sculpture". The portrait was considered by Jefferson's family and friends to be the closest likeness to the man. As Miles tells us, Jefferson's daughter, Martha Jefferson Randolph, said of the three portraits that the Medallion Portrait "best gives the shape of his magnificent head and its peculiar pose". In 1815 Jefferson loaned the Medallion Portrait to the physician and painter, William Thornton, who first copied it in Swiss crayons for the Library of Congress, before making three painted copies.

Watercolor and crayon on paper - Fogg Art Museum, Harvard University Art Museums, Cambridge, Massachusetts

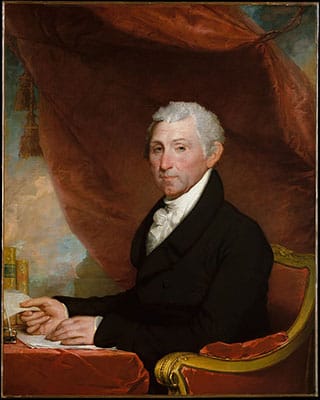

James Monroe

The fifth president of the United States, James Monroe, is depicted formally in this portrait. Seated at a desk in a red velvet chair, he stares out at the viewer, his hands resting on a set of papers, as if taking a momentary break from his work. The opulent background in which he is seated includes a red velvet curtain pulled back with golden colored tassels to reveal a cloudy sky and the slightest hint of a marble column. New York's Met Museum writes, "The three-quarter pose at a desk with books and papers, the billowing drapery, and the liberal use of strong, pure red are all elements of a formula that Stuart, like the Spanish Goya, frequently employed in portraits of statesman".

This is one of a series of portraits the gallerist John Doggett commissioned Stuart to paint of America's first five presidents. This, and his portrait of James Madison, are all that remain today of a commission Stuart accepted late in his career (the other three burned in a fire when they were presented in an exhibition in 1851 at the Library of Congress). Curator Ellen G. Miles explains, when this and the four other portraits in the series were exhibited in 1822, it was well received and, "a writer in the Boston Daily Advertiser for June 20, 1822, said, 'Had Mr. Stuart never painted anything else, these alone would be sufficient to 'make his fame' with posterity. No one...has ever surpassed him in fixing the very soul on canvas; but in the present instance he has done more; he has invested the individual of nature with the ideal of art'".

Oil on canvas - Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, New York

Biography of Gilbert Stuart

Childhood and Education

Gilbert Stuart was the youngest of three children born to parents Gilbert Stuart Sr. and Elizabeth Anthony. Stuart Sr. was a Scottish millwright who immigrated to New England where he ran a snuff mill with his compatriot, Dr. Thomas Moffatt. In 1760, following the failure of the snuff business, the Stuarts moved to a small property in Newport, Rhode Island, from where the family ran a retail business. According to curator Carrie Rebora Barratt, once there, Stuart "learned to sketch faces and caricatures from an African slave [named] Neptune Thurston". Stuart's passion for drawing was shared with his best friend, Benjamin Waterhouse (the future co-founder and professor of Harvard Medical School).

Stuart's first public recognition came when he was thirteen and participated in an art contest in which his skill at painting human faces was widely applauded. It was a significant moment for the teenage boy and marked his first step towards a career dedicated to portraiture (Stuart would later reflect, "no man ever painted history if he could obtain employment in portraits").

Early Training

In 1769, a family friend introduced Stuart to the Scottish portraitist, Cosmo Alexander, who came to Newport as part of his tour of the American colonies. Alexander took Stuart on his journey through the southern colonies, where they visited places such as Williamsburg, Norfolk, and Charleston. In 1771, the pair travelled to Edinburgh, where Stuart continued his mentorship under Alexander. Sadly, Alexander's died suddenly in August 1772 and left a 17-year-old Stuart stranded in Scotland. The Historian, Areeba Ahmed writes "What happened to Stuart after Alexander's death is a bit unclear, but most historians conclude that Alexander's brother-in-law, Sir George Chalmers, became his guardian. Chalmers, however, soon abandoned Stuart, most likely due to the fact that Chalmers was severely in debt. Left in dire financial straits, Stuart eventually managed to make his way back to Newport, but he hardly ever referred to this experience again. It is unclear whether he attended the University of Glasgow during his time in Scotland, and while his degree of formal education is uncertain, those who observed and were acquainted with Stuart later in life considered him to be well-read and literary-minded".

Stuart arrived back in Newport in late 1773. He was able to earn a modest income from painting the portraits of local merchant families. Stuart was visiting Boston when the War of Independence began in April 1775. On his return to Newport, he found himself in strong disagreement with the beliefs of his loyalist father (Waterhouse later recalled Stuart saying "Hang the King, what is he to us? He lives too far off to do us any good"). Rather than move with his family to Nova Scotia, Stuart decided to follow the path of other eighteenth century American artists and traveled to mainland Europe before setting sail for London in September 1775, where he hoped to join Waterhouse who was already in the city studying medicine.

Mature Period

By the time Stuart arrived in London, however, Waterhouse had left for medical school in Edinburgh. Stuart was alone, with what little money he had earned coming from playing the organ in a local church. Ahmed writes, "Eventually, Waterhouse returned to London and found Stuart depressed and living in a boardinghouse. Despite his dedication to his medical career, Waterhouse remained deeply invested in his friend's art. He took it upon himself to reinvigorate Stuart's artistic spirits and for a while supported him financially by helping him obtain commissions and often paying off debts that Stuart frequently incurred". Stuart often took on commissions (and accepted payment) without completing the works. As Ahmed states, "This habit, along with indebtedness, were problems that persisted throughout Stuart's life".

Having gained renewed confidence through his painting, Stuart gathered the courage to introduce himself to Benjamin West, an American artist who, since his arrival in England 1763 has risen to the rank of "Historical Painter to the King". West was welcoming of this young and enthusiastic compatriot. He employed him as his assistant and provided him with a studio and a place to stay. Stuart worked under West's tutelage for the next decade. In that time Stuart's own reputation grew as a portrait painter. He took to the Grand Manner style, which descended from ancient Roman sculpture and Renaissance paintings, and which was exemplified by the art and teachings of Sir Joshua Reynolds. In Grand Manner portraiture (especially when full length and/or life size) the sitter was posed in tasteful settings (flanked by classical architecture, or posed in wooded glens, for instance), and completed by costumes and props, that combined to convey their dignity and status. Ahmed writes, "Some distinguishing characteristics of [Stuart's] art were his liberal use of color and how he often painted without the use of sketches. Stuart developed his portraiture in the European style at the time, but his attention to detail and expression were skills he particularly cultivated". As his reputation grew, Stuart started to exhibit works at the Royal Academy, including masterful full-length portraits like, The Skater (1782), and Captain John Gell (1786).

Stuart's most important patron at this time was Duke Hugh Percy. Sotheby's auction house says of their friendship, "Extravagant and generous [Percy] was one of the richest men in England and an important and long standing sponsor of Stuart's, whom he rescued from debt in 1785 and who took on something of a role akin to that of a court painter to the Percy household. Percy was therefore a crucial early patron of an artist who went on to become one of the greatest American portrait painters in history. As well as the portrait of Joseph Brant [war chief of the Iroquois Nation] Stuart painted several half-length portraits of the Duke himself, full-length portraits of the Duke and the Duchess, as well as a large scale portrait of his four children".

In 1786, Stuart met and fell in love with Charlotte Coates, a woman thirteen years his junior. Despite her father's concerns about his lack of stable income, and what was perceived as his reckless spending habits, the pair married in 1786. Stuart stated that Charlotte "relieved him from all the cares of this life". The couple would have twelve children, seven of whom would predecease them. (Two of Stuart's children were heirs to his artistic talents. His son Charles served as one of his artist assistants before his death from tuberculosis in 1813 at the age of twenty-six, while one of his daughters, Jane Stuart, continued the Stuart legacy by herself becoming a consummate portraitist.)

Despite his success, Stuart fell into debt, due in no small part to his extravagant lifestyle. In August 1787, in an attempt to escape his creditors, Stuart moved with his family to Dublin. With little serious competition, he was soon able to establish himself as the best portraitist in the country and many aspiring artists came to him for mentorship. Probably Stuart's most important Irish commission was that of Lord Chancellor of Ireland, John FitzGibbon. According to Barratt, "there can be no question in general of Stuart's savvy approach to his clientele, and for FitzGibbon, a man as approachable as he was ruthless, as generous as he was mean, Stuart invoked a tried and true compositional format, harking back to [Anthony] Van Dyck and looking to [Joshua] Reynolds to give his demanding and flamboyant, but perhaps relatively unsophisticated, client a work appropriate to his cosmopolitan interior décor". Despite such prestigious commissions, however, financial difficulties continued to plague Stuart (who could not shake his habit of accepting, but not completing, commissions) and he was incarcerated for debt at least once during his six years in Dublin.

Later Period

Stuart's driving ambition was to paint the portrait of America's first president, George Washington. In a letter to James Dowling Herbert, an artist and writer whom Stuart had befriended in Ireland, he stated "I expect to make a fortune by Washington alone [...] I calculate upon making a plurality of his portraits, whole lengths, will enable me to realize; and if I should be fortunate, I will repay my English and Irish creditors. To Ireland and England I shall bid adieu".

His European adventure over, the 38-year-old Stuart arrived in America in May of 1793 where he quickly established an artist's practice in New York City. According to Barratt, "Stuart had situated himself in New York in the right place [...] in the center of the fashionable section of town, at the right time, and exercised a remarkably measured approach to painting clients, depending on their character, station, and requirements. In New York, he concocted a style of painting that combined, in varying degree, the fluidity of his best English pictures with the specificity of his Irish work, a startlingly brilliant combination". However, New York would not allow Stuart to fulfill his great ambition: to paint the portrait of the first president of the United States. Stuart painted a number of prominent public figures in New York, one of which was John Jay, the Chief Justice of the United States Supreme Court. It was Jay who wrote a letter of introduction to Washington on Stuart's behalf. With his great ambition within his grasp, Stuart and his family relocated to Philadelphia in November 1794.

Stuart painted Washington for the first time in 1795, a portrait now referred to as the Vaughan Portrait (after its first owner, the Anglo-Irish merchant, Samuel Vaughn). Stuart was unhappy with the finished work, however. As Barratt states, "An artist accustomed to easily engaging and enlivening his clients with conversation and jokes, Stuart was at a loss with Washington: 'An apathy seemed to seize him and a vacuity spread over his countenance, most appalling to paint'". Stuart made two additional portraits from memory (both of which displeased him) before Washington sat for him a second time in 1796. On this occasion, the First Lady, Martha, had commissioned matching portraits of her and her husband, with the president's portrait becoming known as the Athenaeum Portrait.

Although the painting was unfinished (it features in fact only a bust of the president) the Athenaeum Portrait is considered to be Stuart's most important work, and undoubtedly the preeminent George Washington portrait. (Its fame was sealed in 1869 when it featured on the one-dollar bill. Elizabeth Hosier of the U.S. Currency Education Program writes, "Ironically, the portrait appearing on the bill, is one that the man himself was likely not particularly fond of. [...] Today, the original painting is on display at the National Portrait Gallery in Washington D.C. Despite being the most recognized painting of [Washington], it is an unfinished work. In the painting, [Washington's] cheeks are puffed out and his lips pursed in discomfort. Around the same time he complained about his new set of dentures not fitting him correctly and causing him pain. Due to his constant concern for his appearance and demeanor, he would probably not appreciate our widespread use of this portrait".)

Stuart used the Athenaeum Portrait as the basis for his Lansdowne Portrait, this time a full-body portrait commissioned by the Marquis of Lansdowne (William Petty) and the Philadelphia socialite Anne Willing Bingham. Curator Ellen G. Miles says of The Lansdowne Portrait, its "pictorial elements carry [...] meaning about the man and the time in which the painting was made. The Neoclassical decorative elements of the furniture which did not exist, are derived from the Great Seal of the United States, authorized by Congress in 1782 and still in use today. The oval medallion on the back of the armchair is draped with laurel, a symbol of victory [...]. Two eagles at the top of the table leg are in upright positions, each holding a bundle of arrows - a symbol of war [...] Under the table are large books titled General Orders, American Revolution, and Constitution & Laws of the United States. These refer to past events: Washington's roles as commander of the American colonial army and as president of the Constitutional Convention of 1787 during the debates over the structure of the new government".

While in Philadelphia Stuart painted other important sitters, including the future second president, John Adams and his wife Abigail, visiting dignitaries, and local important merchants. Already in the habit of copying his portraits, this practice now became a key element of Stuart's financial success when patriots began to buy copies of his portraits of Washington to hang in their own homes. The demand for copies came with unforeseen problems, however, namely the inability for Stuart to stop others from making unauthorized copies of his original paintings. As Barratt explains, Stuart, "struggled to protect his copyright of the Washington portraits, arguing first with William Bingham about James Heath's engraving of the Lansdowne portrait, and then with John E, Sword, whose Cantonese copies of the Athenaeum portrait, made as reverse paintings on glass and sold in the city, led to a lawsuit and a court victory for Stuart in 1802". Through these actions, Stuart became the first artist to win the right to control copyright over his own works in America.

Stuart moved with his family to Washington D.C. in 1803 (after the federal capital moved to the city). His painting practice did not suffer from the move and Stuart maintained his impressive list of clientele, which included the future president, Thomas Jefferson. Offsetting his professional good fortune, Stuart's health had started its steady decline. He suffered two bouts of malaria which led to a deep depression. His output suffered, and while his talent was never in question, Stuart's easy way with sitters suffered from his unpredictable mood swings. One of Stuart's clients in Washington, Massachusetts Senator Jonathan Mason (of whom he painted portraits of him, his wife, and two daughters), encouraged the artist to move to Boston with the promise of several commissions from well-connected families. In 1805, Stuart and his family relocated to the city.

In Boston, Stuart, who was now just shy of his fiftieth birthday, became the city's most famous artist. In addition to his paying clients, Stuart also found himself in demand with younger artists wishing to learn from him. Amongst his students were Jacob Eichholtz, Thomas Sully, and his nephew, Gilbert Stuart Newton. According to Professor Dorinda Evans, "those aspirants who visited Stuart were usually warmly received [...] and not infrequently given free lessons. Quite a few of them carefully recorded the master's palette colors and his way of applying flesh color". Stuart's health continued to suffer, however, with his depression becoming more severe in 1817, following the death of his son Charles from tuberculosis. He suffered simultaneously from gout and asthma, and his face and left arm became paralyzed following a stroke in 1824. Stuart still made the effort to paint despite his physical limitations, but on July 9, 1828, Stuart died at the age of seventy-two. His extravagant spending habits and poor money management meant that his family was left nearly penniless. The Stuart family could not even afford a proper burial and his remains were rested in an unmarked grave.

The Legacy of Gilbert Stuart

Stuart was the preeminent portrait painter of early American art. His pictures provide the authoritative visual record of many of the new republic's most powerful figures (and their families) such as politicians - including the first six presidents - diplomats, lawyers, and merchants. Stuart revolutionized portraiture in America by bringing a more relaxed mindset to the stately and gracious Grand Manner model he had mastered while studying in London. By adopting the loose shading of the "European style", Stuart brought a subtle compositional depth to his portraits, while he demonstrated a knack for capturing the likeness and personality of his sitters through carefully considered choices in color, dress, and staging. As Barratt writes, "Stuart possessed abundant natural talent which he devoted to the representation of human likeness and character, bringing his witty and irascible manner to bear on each of his works, including his incisive portraits of George Washington".

According to curator Carrie Rebora Barratt, Stuart also "established the business of portraiture for this generation in America and cultivated the notion that it was a privilege to sit for an expert painter". He was happy to give freely of his time and expertise to new students and was considered a great authority in artistic matters. Historian Amy Tikkanen writes, "Stuart's work was hailed by his contemporaries, and modern critics have confirmed this judgment, praising his brushwork, luminous colour, and psychological penetration". Tikkanen adds, however, that while artists such as John Vanderlyn, Thomas Sully, and John Neagle skillfully applied Stuart's working methods (including painting directly onto a canvas or panel), "less talented artists [...] reduced his style to a formula that was reflected in much American portraiture of the succeeding generation".

Influences and Connections

-

![Thomas Gainsborough]() Thomas Gainsborough

Thomas Gainsborough -

![Joshua Reynolds]() Joshua Reynolds

Joshua Reynolds -

![Anthony Van Dyck]() Anthony Van Dyck

Anthony Van Dyck -

![Benjamin West]() Benjamin West

Benjamin West - William Dobson

- John Doggett

- William Dunlap

- John Jay

- Benjamin Waterhouse

-

![Grand Manner Portraiture]() Grand Manner Portraiture

Grand Manner Portraiture -

![Neoclassicism]() Neoclassicism

Neoclassicism -

![Renaissance]() Renaissance

Renaissance - Portrait Painting

-

![John Trumbull]() John Trumbull

John Trumbull - John Neagle

- Gilbert Stuart Newton

- Rembrandt Peale

- Thomas Sully

- John Doggett

- William Dunlap

- John Jay

- Benjamin Waterhouse

-

![Neoclassicism]() Neoclassicism

Neoclassicism -

![Realism]() Realism

Realism - Portrait Painting

Ask The Art Story AI

Ask The Art Story AI