Summary of Henry Ossawa Tanner

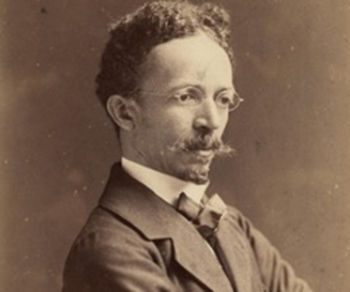

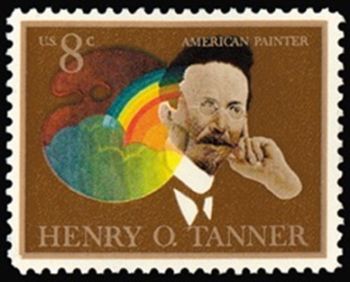

In the late 1800s, amidst America's still largely unenlightened attitude toward race equality, Henry Ossawa Tanner would break from all societal projections and boldly expatriate to Europe where he became the first African American man to achieve international acclaim as a painter. Eschewing the norm not only allowed him to carve his own course through life, but also to transform religious genre painting, the field in which he is best known. He remains the most distinguished African American artist of the nineteenth century.

Accomplishments

- Tanner's spiritual faith was informed early by his relationship with his minister father and would eventually inspire Tanner's most prolific subject matter in his art - religion. Yet, Tanner would contribute to the evolution of the genre by departing from traditional representations of narrative biblical scenes and carving out his own symbolic versions that modernized the field.

- Tanner was adamant about not having his race define him, a motivation that his life in Paris allowed him to adhere to. Yet, ironically, two of his most memorable paintings feature poignant scenes between an African American elder figure and a young African American junior figure. Even so, some have criticized his intentional dissociation from his own foundational black culture.

- Tanner's curiosity about other cultures and his willingness to continually evolve his artistic abilities with an open mind led him to consistently expand his styles and subject matters. Over the course of his career, he dabbled in Realism, SymbolismSymbolism, Impressionism, and Orientalism, albeit always with a light touch while still lending his own distinct voice to each finished creation.

The Life of Henry Ossawa Tanner

Despite being one of the leading religious genre painters of his age, Henry Ossawa Tanner is best remembered for two paintings depicting domestic scenes of African American life and for being the first black artist to gain international fame. Tanner would most likely have found this ironic as he chose to live abroad rather than in America so that his race would not be used to define his art and once famously stated, "in Paris...no one regards me curiously....I am simply 'M. Tanner, an American artist.' Nobody knows or cares what was the complexion of my forebears. I live and work there on terms of absolute social equality."

Important Art by Henry Ossawa Tanner

The Banjo Lesson

In what is Tanner's best-known work, an elderly man is teaching a young boy, most likely his grandson, to play the banjo in the setting of a sparsely furnished room. In an intimate depiction, the boy sits on the man's lap, his arms almost too short to properly reach around the instrument to touch the strings as both seriously focus on their task.

The work is important because it is one of only a few genre paintings that Tanner would create in an oeuvre largely dominated by religious works. Secondly, it depicts everyday life from an African-American lens, which was not commonly seen at the time in the art canon at large, nor did the artist want to be creatively defined by his race. Yet, Tanner painted this scene during a brief stay in Philadelphia and may well have been affected by the plight of African Americans in his native country. He wrote of this time in the third person stating, "since his return from Europe he has painted mostly Negro subjects, he feels drawn to such subjects on account of the newness of the field and because of a desire to represent the serious, and pathetic side of life among them, and it is his thought that other things being equal, he who has most sympathy with his subjects will obtain the best results. To his mind many of the artists who have represented Negro life have only seen the comic, the ludicrous side of it, and have lacked sympathy with and appreciation for the warm big heart that dwells within such a rough exterior."

Artistically, the work highlights Tanner's skill in the field of Realism and shows his training with figures and scene painting that began with his teacher artist Thomas Eakins in Philadelphia a few years before. Furthermore, this painting can be considered a statement about the importance of teaching and passing on information. According to Professor Marcus Bruce, this canvas "...document[s] the artist's exploration and depiction of folk culture and its transmission from one generation to the next.

Oil on canvas - Collection of Hampton University Museum, Hampton, Virginia

The Thankful Poor

In Tanner's The Thankful Poor, an elderly man and his young grandson sit at a small table where a simple meal is laid. The two white plates are empty as they cannot begin eating until they have first said a prayer over their food which they are in the process of doing with their heads bowed down onto their folded hands.

This painting is the second of only two paintings Tanner created of scenes of domestic life featuring African Americans. He would soon after devote the majority of his future career to religious genre scenes and interestingly here we see him make a reference to this future focus. While this painting is often used today to link him to his role as an African-American painter it can also be seen as a statement about his interest in religious themes in that prayer and devotion to God is at the heart of this painting. It may also reference the influence Tanner's minister father had on the young painter himself and the course of life that he followed where reverence and art served integral parts in his development as a man. Another interpretation of this work is that it is influenced by his time in northwest France and the people he saw there which deeply inspired artists such as Paul Gauguin. According to curator Anna O. Marley, "Tanner's time spent in Brittany, absorbing the influence of the modern French academic tradition of peasant genre scenes[...]led him to create innovative portrayals of African Americans based on traditional genre scenes. He did this by painting respectful, naturalistic depictions of African Americans that stood in sharp contrast to other, unfortunately more typical, caricatured images."

While this work highlights the Realism with which Tanner rendered many of his works, it also shows the sway that modern Paris was beginning to have on the artist. Here the influence of Impressionism is evident in both the softening and loosening of the brushstrokes used to render certain items including the wall and tablecloth as well as the importance of light which streams through the window casting a glow on the figures and their meal.

Oil on canvas - Private Collection

The Resurrection of Lazarus

In this biblically themed painting from the Gospel of John, Tanner depicts Jesus in a room with the dead Lazarus who lies on the ground, wrapped in white cloth with his head being cradled by a figure behind him. Jesus's arms are outstretched as he commands Lazarus to rise. A crowd in the background has gathered to mourn.

While Europe had a long tradition of artists creating grand religious genre paintings, this work provides an example of how Tanner distinguished himself by modernizing the subject. As curator Anna O. Marley states, "...Tanner's spectators are brought into the light via the miracle occurring before them. Tanner's painting [...]is much more intimate [...with a] more humble representation of Jesus." Author Marcia M. Mathews discusses how Tanner distinguished himself from other painters of this subject stating, "Tanner's version of the familiar theme had none of the shallow sentimentality so often seen in religious pictures on the Salon walls. His picture is a somber one."

While this work is one of Tanner's earliest paintings featuring a religious theme, it was so well received that it helped solidify the direction of his career. According to art historian Marc Simpson, "by every measure, The Resurrection of Lazarus was a milestone in Henry Ossawa Tanner's career" and it "...elicited high critical praise and earned a third-class gold medal in the Salon of 1897. When the French state acquired the work (and eventually placed it in the Musée du Luxembourg, the official repository for contemporary art), and the press on both sides of the Atlantic acclaimed the picture and lauded its maker. [...] The painting's success [...] established Tanner among the era's foremost makers of religious art." Of important note, American department store owner Rodman Wanamaker was so impressed with this painting and what he considered Tanner's potential that he sponsored two trips for the artist to the Holy Land; something that would greatly inspire his work.

Oil on canvas - Collection of Musée d'Orsay, Paris, France

Interior of a Mosque, Cairo

As the title reflects, Tanner presents the interior of a mosque, highlighting the architecture of the space with its curving arches and domes and the detailed geometric patterns on the wall. Two figures populate the scene, engaged in silent prayer.

Tanner's modern approach to painting is evident here in the way in which he approached the subject matter. According to curator Anna O. Marley, his painting focused on, "...the architecture of the Muslim world at the time [...and] seems to have been more interested in conveying the play of light in the darkened, dramatic space of the mosque than in depicting the visitors within it."

Tanner was inspired to paint this and other similar works from two visits he took to the Holy Land beginning in 1897. These journeys informed his growing interest in the Orientalism art movement, which was sweeping across Europe, and furthered his earlier genre painting work by showcasing his interest in portraying slices of real life. His curiosity about other cultures and his exploration into all aspects of religion, both historical and contemporary are also exemplified.

Oil on canvas - Collection of Museum of Fine Arts, Boston, Massachusetts

The Annunciation

In The Annunciation, Tanner glowingly reveals the moment the angel Gabriel (rendered here in the form of a glowing column of light) visits Mary to tell her that she will carry the Christ child. The young woman is seated on a bed in the corner of her room wearing robes as if she has just awakened from slumber.

Tanner who by this point in his career had already established himself as a major player in the field of religious genre painting, again presents a thoroughly modern interpretation of an often-depicted biblical scene. As Professor Marcus Bruce explains, "...unlike more traditional depictions of the scene, in which Gabriel is shown as an enormous, winged figure hovering before Mary, Tanner renders Gabriel as a brilliant burst of light, thereby redirecting the viewer's gaze to Mary and the moment of conception. [...Here] the locale of a momentous event is depicted in a familiar yet unlikely place: the unadorned bedroom of a young woman who is awakened in the dead of night. Tanner's interpretation of the moment of conception, and perhaps revelation, serves as an example of how he used religious subjects to offer viewers another perspective from which to see themselves and their experiences: extraordinary events take place in the most unlikely places and among the most unlikely people." The idea that viewers can find something in such a scene to relate to their own lives was a thoroughly modern approach to a religious subject and helped contribute to how Tanner stood out in this field.

Also, highly evident in this piece is the influence of Orientalism on Tanner's art and according to Bruce, "...the arching columns of the walls, the thickly woven and patterned rugs on the stone floors, the garments draped over a chair, and the luxurious bedclothes falling from the bed reveal Tanner's fascination with the visual idioms of Orientalism; they are employed here to lend an air of authenticity in Tanner's re-creation of the biblical world."

Oil on canvas - Collection of Philadelphia Museum of Art, Philadelphia, Pennsylvania

Salome

If not for the title Salome, the subject of this mysteriously composed painting might now have been understood by viewers as the woman, who according to the New Testament, was responsible for the beheading of John the Baptist after dancing for King Herod.

In describing this depiction, art historian Hélène Valance states, that here Tanner, "...stages an unusually sensuous feminine figure cast in a strong contrasting light. Like John the Baptist, whose gruesome severed head sits in the foreground, Salome - except for a flash of white, threatening teeth - is visually decapitated by the shadows hanging over her face. The thinly veiled curves of her hips and stomach emerge from the dark, as though she were exposed to a bright spotlight."

The importance of this work lies in the fact that it is unlike any other in Tanner's oeuvre. While he made several religious paintings, this one uncharacteristically featured a nude whose sensual depiction borders on the erotic. There is a degree of uncertainty surrounding the work in that historians have failed to definitively understand the artist's motivations and why he rendered the subject the way he did. Some interestingly have linked it to his fascination with the Symbolism art movement. According to curator Robert Cozzolino, "Charles C. Eldredge included Tanner's Salome [...]in his groundbreaking and still unique book on American Symbolists, a group who may form the most visually persuasive link between Tanner and the degenerative eroticism that was rampant among the Belgian and French Symbolists. However, Salome was an anomaly in Tanner's work, and the context in which he explored it remains mysterious." What is clear is this painting is a marked departure for the usually reserved artist.

Oil on canvas - Collection of Smithsonian American Art Museum, Washington DC

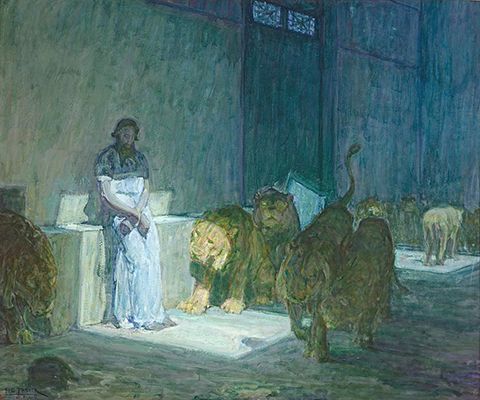

Daniel in the Lions' Den

The Old Testament story of Daniel remaining unharmed while in a den of lions due to his faith in God is the subject of this painting. A pensive yet serene Daniel sits in the left corner of the painting as four lions walk past him, and still other lions can be seen in the background.

As in so many of his religious genre paintings, light plays a key role but here. Interestingly, it does not shine on Daniel's face which would be the traditionally expected portrayal. Instead, Daniel's tied hands are centrally lit, resting crossed in his lap as if to reinforce the submission to his faith in God as greater than his fear. The light can also be seen as a sign of divine presence surrounding Daniel. This interpretation is echoed on the Los Angeles County Museum of Art's website where the painting resides: "...Daniel appears calm, strengthened by his inner spiritual belief, and Tanner's use of a bluegreen palette heightened this meditative mood."

This is the artist's second rendering of this subject; the first of which was an 1896 painting, now lost, which marked Tanner's first foray into the field of religious genre painting. It caused the art world to take note of him and helped to launch the start of his career. While, this piece is similar to the original, also noted on the Los Angeles County website, "in the second version, Tanner eliminated the ceiling to focus more on the figure...." This perhaps marks a maturity of his work in which he moved away from a need to create grand religious scenes to instead focus more on a particular element of a story; a markedly more modern approach and a departure from the work of European religious genre painters of the past.

Oil on paper mounted on canvas - Collection of Los Angeles County Museum of Art, Los Angeles, California

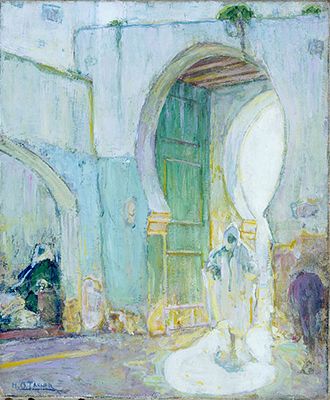

Gateway, Tangier

This painting is one of several Tanner was inspired to create after several trips to North Africa. Here attention is directed at the gateway entrance into the heart of the Moroccan city of Tangier. The open, rounded archway dominates the canvas beneath which stands a figure who has passed through the gate; his diminutive size intended to emphasize the height of the great entranceway. The entire scene is rendered in soft pastels and shows the important role that color played in Tanner's later works. According to the website of the Saint Louis Art Museum, "the blue tones and loose brushwork of this painting typify Henry Ossawa Tanner's most successful experiments with color composition and application of paint."

Like his forays to the Holy Land years earlier, Tanner's Moroccan journeys were a source of great inspiration, especially in introducing the artist to foreign architecture - a particular pleasure of his. In fact, according to curator Adrienne L. Childs, "Tanner's modernist works from this period tend to emphasize the picturesque nature of North Africa and focus on secular subjects, such as the play of sunlight on the whitewashed architecture and views of the cities and their shrouded inhabitants." Interestingly, the renderings first and foremost can be viewed as presenting Tanner's perspective of the countries he visited and as Childs explains, "Tanner's Moroccan gateways and cityscapes denote the limits of his incursion into Oriental spaces. He does not attempt to project a conception of the private Moroccan spaces in the manner of traditional Orientalists [...]. Instead, Tanner presents stylized renderings of public spaces subtly animated by the movements of indistinct figures." He was respectfully an observer of these cities not an inhabitant and paints his scenes accordingly.

Oil on canvas - Collection of Saint Louis Art Museum, Saint Louis, Missouri

The Arch

Paris's iconic Arc de Triomphe dominates this mature work. Beneath the iconic monument's arch is a roughly built cenotaph, or empty tomb, which at the time was intended to be an homage to the French soldiers who had lost their lives in World War I. In the foreground two pairs of people are viewing the monument; on the left side a mother and child and on the right two veterans.

This work is an important example of the paintings Tanner made during World War I. While at first, he found it difficult to be creative in the early years of the war, his work with the American Red Cross, and later the Bureau of Publicity where he sketched images of the war, provided him much inspiration. This work contains little of the realism of his earlier canvases and is rendered in an impressionistic style with loose brushstrokes and a softer color palette.

While Tanner was not known for expressing political views in his work, this painting offers a rare exception. Describing how he achieves this, curator Anna O. Marley states, "[art historian] Hélène Valance perceptively argues that Tanner symbolically paired the widow and orphan with the two veterans, making these anonymous victims of war the preeminent protagonists of the scene. The crowd behind these figures remains a shapeless mass, and Tanner infuses an eternal spirit into what was an ephemeral monument, which - like the multitudes of lives taken in the war - would soon crumble to dust. The temporary nature of the cenotaph stands in contrast to the solid arch, suggesting both loss and continuity. This painting can thus be read as both an elegy for what was lost and a hope for what remained."

Oil on canvas - Collection Brooklyn Museum, Brooklyn, New York

Biography of Henry Ossawa Tanner

Childhood and Education

Henry Ossawa Tanner was the first of nine children born to Sarah Elizabeth Miller and Benjamin Tucker Tanner in Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania. Religion and racial justice were important aspects of Tanner's early family life. His father, a deeply religious man, served as a bishop in the African Methodist Episcopal church and his mother, who had been born a slave, helped to organize one of the first missionary organizations for black women. Even Tanner's own middle name supports these familial beliefs as it was derived from the Kansas town of Osawatomie where abolitionist John Brown began his career advocating against slavery.

Tanner developed an interest in art at an early age and could trace it back to a single incident when during a park walk with his father, he witnessed an artist painting a landscape outdoors at an easel. Reflecting on this years later, Tanner stated, "...a long conversation that night [with my father] produced fifteen cents and this, early the next morning, secured from a common paint shop some dry colors and a couple of scraggy brushes. Then I was out immediately for a sketch. I went straight to the spot where I had seen the artist the day before....Coming home that night, I examined the sketch from all points of view, upside down and down side up decidedly admiring and well content with my first effort."

As education was important and highly valued by his family, initially Tanner's father felt his son's passion for art should be considered only a hobby. So, when Tanner did not want to enter the church after graduating from school in 1877, an apprenticeship was arranged for him at a family friend's flour business. The work proved laborious and an unhappy Tanner soon became ill. Empathizing with his son's mental and physical distress, Tanner's father finally agreed to support his career as an artist.

Early Training

Ready to embrace his artistic dream, twenty-year-old Tanner enrolled at the Pennsylvania Academy of Fine Arts as its first African American attendee. A little over a year later, in January 1881, he became a student in the Realists Thomas Eakins' life drawing class. Under Eakins' tutelage, he changed his initial interest in marine scenes to an interest in painting animals and figures. According to curator Anna O. Marley, "Tanner was so devoted to animal painting that he bought a sheep to serve as a model for his pastoral compositions." Tanner flourished while studying and as Marley explains, his "...first stab at the elevated academic genre of history painting began under the tutelage of Eakins. The two men had a mutual respect for each other, and Eakins had a profound early influence on Tanner...." A decade later, Eakins would pay tribute to the rising young artist by painting his former student's portrait.

During his schooling, and in the years directly after he left the academy, money remained an issue for Tanner. So, in addition to spending summers working in Atlantic City at resorts, he attempted, rather unsuccessfully, to sell drawings to publishers. In 1889, having finished his studies, he moved to Atlanta, Georgia and established a photography studio. While the business failed almost as soon as it opened, he did meet his future life-changing patrons Bishop and Mrs. Joseph Crane Hartzell and Wesley N. Clifford. Clifford, a teacher at Clark University in North Carolina, invited Tanner to join him there for a time to teach, which he did for a year. Perhaps more importantly, Mrs. Hartzell was responsible for an exhibition of Tanner's works in Cincinnati, after which she and her husband provided the funds for him to travel to Europe for further art study; something Tanner desperately longed to do.

When Tanner set sail for Europe on January 4, 1891 it was with the intention to settle in Rome. However, after first briefly visiting London, he traveled on to Paris where he was so taken with the city that he decided to stay. Once settled, he enrolled at the Académie Julian to study art. Tanner immediately took to his studies under the teachers Jean-Joseph Benjamin Constant and Jean-Paul Laurens. He became fascinated with the Symbolist and Impressionist art movements as well as the French countryside after taking summer trips to Brittany. It was also at this time that he began to seriously work on genre paintings, popular works of the time that depicted scenes from everyday life, including his well-known The Banjo Lesson in 1893.

Mature Period

Tanner found he could easily settle into life in Paris and quickly developed a circle of both French and American friends. Importantly, after joining the American Art Club, he met American department store owner Rodman Wannamaker who became a patron and supporter. He also began exhibiting in Paris salons and, after a few years, he made the seminal decision to focus on painting religious scenes; something for which he would become best known. Key paintings followed including the now lost Daniel in the Lions' Den (1896), which, as his debut in this genre, caused quite a stir among the Paris Salon viewing public. Many have tried to understand the reason for this shift in subject matter from scenes of normal life to visual representations of spiritual and biblical narratives and scenes. Some suggest it was a way to process his beliefs and pay tribute to his foundational religious upbringing, but the style was also burgeoning in Europe at the time and he had become interested in these paintings as a student at both the salons and on visits to Paris museums.

Tanner's popularity as an American artist in Paris grew rapidly, boosted by a distinct honor from the French government when it purchased his painting The Resurrection of Lazarus (1896). As his reputation in the religious genre painting style grew, Wanamaker sponsored a trip for Tanner to the Middle East which he took in 1897. It was the first of two such journeys (the second was a year later) where he quickly absorbed all the sights and culture that the Holy Land had to offer. These trips inspired paintings steeped in the Orientalism style that had begun to fascinate Tanner. These works also became popular in his native country and in 1897 his Lazarus painting was reproduced in Harper's Weekly magazine.

As his professional life blossomed, so did Tanner's personal life. In 1898, Tanner met Jessie Macauley Olssen, an American singer of Swedish descent who was on a vacation with her family in France. They would marry a year later on December 14, 1899, and set up their life together in Paris. The city proved a perfect place for Tanner as he felt he could be himself in a place where his art was judged on its merits alone without his African American heritage entering the equation. It was also a receptive city for his family since his marriage to a white woman fifteen years his junior and the birth of his racially blended child, a son named Jesse who was born in September of 1903, would not have been widely accepted in America at the time.

Despite the discrimination he felt he would have endured in America, Tanner's reputation continued to grow there and on a return visit home in 1902, his friend and patron Atherton Curtis convinced him to try settling in Mount Kisco, New York where an artist colony had been established. The pull of Paris was too strong however, and Tanner and his family returned to Europe after only six months. He did however like the camaraderie he had experienced with fellow artists. So, in addition to his apartment and studio in Paris, Tanner bought a home in Trépied, France which was near an artist colony in Étaples of which he became an active part and where he and his family spent many summers.

Once settled back in Europe, Tanner felt comfortable taking a second series of trips to further his interest in Orientalism. Just as his prior visits to the Holy Land had inspired his art, beginning around 1910 Tanner embarked on trips to North Africa where he was especially drawn to the sights and sounds of the markets in Morocco and the architecture of Tangiers. He captured these impressions through his paintings of the period.

Tanner's productivity came to an abrupt halt with the outbreak of World War I. Unlike many Americans living in Europe at the time, Tanner did not return home but did initially believe it would be safer to leave Trépied and briefly sought refuge in England. However, he and his family soon found they longed to return to France and did so after only a brief stay. He also struggled creatively during the early years of the war and according to Mathews, "...Tanner found it difficult to paint. The atmosphere of war was not conducive to creative work, for art was of no interest to people who lived in daily apprehension of death." Although being in his fifties prevented him from serving, Tanner felt strongly about doing his part. So, in 1917 he became a lieutenant in the Farm Service Bureau of the American Red Cross and led a campaign to build a vegetable garden around the military hospital and empower recovering wounded soldiers to feel productive in helping to tend and grow the crops. His service continued in the fall of 1918 when Tanner joined the Bureau of Publicity and served as an artist who sketched scenes of the war.

Later Period

After the war ended, Tanner returned to a daily rhythm of creating new work in both his Paris studio and at home in Trépied. Despite the art world's move toward more modern styles of painting, his reputation and the demand for his work, both in Europe and America, continued to grow. In December of 1923 Tanner made his last visit to America to promote his work. He was also, in that year, elected Chevalier of Legion of Honor by the French government; an honor in which he took great pride.

Sadly, several tragedies and difficulties befell Tanner in his later years. Jessie, who had returned to America for a visit with her family while her husband stayed behind to work, and who had been feeling tired and generally unwell at the time, grew seriously ill. She was diagnosed with pleurisy. After receiving treatment and recovering for a period, she would return to France and die on September 8, 1925. This loss devastated Tanner, and according to Mathews, "Jessie's death left a vacuum in Henry Tanner's life that was never to be filled. Although he did his best to work, for months he found himself incapable of it."

Tanner was able to find comfort in his relationship with his son who had graduated from Cambridge University with an engineering degree but who, less than a year, later grew ill from nervous exhaustion and had to leave his job. Tanner would devote a great deal of his energy into helping his son get well, even traveling with him during the periods he had to be moved to a nursing home in Saujon, France to recuperate.

Eventually, as his son found healing, Tanner was able to begin painting seriously again. However, the Great Depression impacted his ability to sell his paintings and he suffered some financial setbacks. Still, he painted and exhibited his work and continued the tradition he had begun before the war of meeting with and mentoring many young African-American artists who came to see him in Paris such as Palmer Hayden and William H. Johnson.

Tanner died in his sleep at the age of seventy-seven. The calm, quiet life he had lived was echoed in his death and according to Mathews, "no death could have been more peaceful or less free of suffering. When his friends read in the newspapers that he was gone they were shocked by the suddenness of it. They knew Tanner was old and not very strong, but death had seemed far away. Yet they knew it was the way he would have wanted to go, with the paint still fresh on his last canvas."

The Legacy of Henry Ossawa Tanner

Henry Ossawa Tanner left a great mark on the art world socially as the first African-American artist to achieve international prestige and status. But also, most notably, he redefined religious painting for a modern era. As curator Anna O. Marley explains in describing Tanner's legacy, he spent, "...more than a decade as the leader of an international artist's colony in northern France; [had] a career as a technical innovator who used modern painting techniques to create a transcendent practice that to this day defies easy classification; and finally, [he firmly established] his status as America's preeminent religious artist during the height of the genre's popularity."

Despite his reluctance to be viewed through the lens of his race, it cannot be argued that he left a profound influence on the next generations of black artists, offering them proof that success could be achieved. Even in his own lifetime, many artists traveled to meet with him while he worked in France which helped to shape their careers including Palmer Hayden, William H. Johnson, William Edouard Scott, and Hale Woodruff. Although he was not a direct contributor to the first collective African American art movement known as the Harlem Renaissance, his very existence and accomplishments helped pave the way for it. Contemporary artists today continue to draw inspiration from Tanner's work including Romare Bearden and Kerry James Marshall. Of his influence, Marshall once stated, "black artists had to prove mastery of the tradition in order to own it, and only then could think about moving on," As art historian Richard J. Powell adds, "that an academician and art visionary like Tanner could have relevance in the twenty-first century was not only insinuated in Marshall's statement but corroborated in Marshall's multi-portrait wall installation First (2003)." The piece paid homage to numerous African-American "firsts," including artists, athletes, and thinkers being brought into the public eye for proper recognition of their contributions to the black historical experience.

Influences and Connections

-

![Thomas Eakins]() Thomas Eakins

Thomas Eakins -

![Rembrandt van Rijn]() Rembrandt van Rijn

Rembrandt van Rijn -

![James Whistler]() James Whistler

James Whistler - Jean-Paul Laurens

- Jean Joseph Benjamin-Constant

- Edward Bok

- Atherton Curtis

- Bishop Joseph Crane Hartzell

- J.J. Haverty

- Harrison S. Morris

-

![Romare Bearden]() Romare Bearden

Romare Bearden -

![Kerry James Marshall]() Kerry James Marshall

Kerry James Marshall - Reginald Gammon

- William Harper

- Palmer Hayden

- Edward Bok

- Atherton Curtis

- Bishop Joseph Crane Hartzell

- J.J. Haverty

- Harrison S. Morris

Useful Resources on Henry Ossawa Tanner

- Henry Ossawa Tanner: American ArtistOur PickBy Marica A. Mathews

- Henry Ossawa Tanner: Art, Faith, Race and LegacyBy Naurice Frank Woods, Jr.

Ask The Art Story AI

Ask The Art Story AI