Summary of Alma Thomas

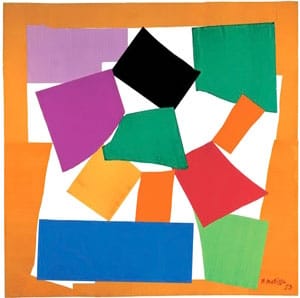

Alma Thomas made a unique and vital contribution to the development of mid-to-late 20th century American abstraction. Her richly colored patterned paintings are considered all the more remarkable given that Thomas's artistic career did not take off until she had reached retirement age. She arrived at her signature "Alma's Stripes" style by borrowing ideas from sources as miscellaneous as Byzantine mosaics, the Pointillism of Georges Seurat, Henri Matisse (especially his famous 1953 Snail collage), the Bauhaus color theorist Johannes Itten, and painters connected to the Washington Color School. As the first African American woman to hold a solo exhibition at New York's prestigious Whitney Museum of American Art, and with her paintings hanging on the presidential walls of the White House, Thomas has served as a role model for women, African Americans, and older artists all at once.

Accomplishments

- Thomas had enjoyed a long (and deeply fulfilling) career in arts education before she emerged as a certified artist. Recognized for her luminous vertical and concentric circles of acrylic blues, reds, greens, and purples (while leaving just enough space for her canvas to "peep through") Thomas's acclaimed "Alma's Stripes" would bring a new facet to the field of painterly abstraction.

- Thomas's most famous works took their stimulus from the colors of the natural world. She drew inspiration from views of her own garden (observed through the windows of her home-cum-studio), and Washington parks. Thomas also called on memories of the wildflowers and peacocks she once played amongst as a child in and around Columbus, Georgia, and on the banks of Alabama's Chattahoochee River.

- In the late 1960s, Thomas became enraptured (like so many people around the world) by early space travel and the first moon landing. The mesmerizing images of earth (as photographed from space), and images of the Luna surface, inspired her to create abstract works in which she imaged what wonderful color formations one might see if floating aimlessly through the outer limits of space.

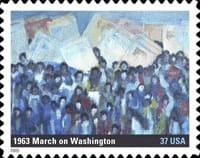

- Although Thomas attended the historical 1963 March for Jobs and Freedom on Washington (and produced three related works), she would resist any expectations placed on her to use her talents as a means of drawing attention to racial and/or gender inequities. Rather, her painting focused exclusively on aesthetic properties. She stated, "Through color, I have sought to concentrate on beauty and happiness, rather than on man's inhumanity to man".

The Life of Alma Thomas

New York's Museum of Modern art writes, "Thomas's career is as unlikely as any in the 20th-century United States [...] she began a career as a painter at nearly 70, and in the course of her remaining two decades made extraordinary work that won widespread acclaim despite its maker being not male, not white, and not in New York".

Important Art by Alma Thomas

Red Abstraction

During her long teaching career (lasting between 1925-60), Thomas's painted in a representational style. Indictive work titles included, In the Studio (1956), Still Life (1957), and Untitled (Standing Nude) (1958). She never felt artistically fulfilled however, stating, "I wasn't happy with that [style] ever". In the late 1950s, inspired by the rise of Abstract Expressionism, Color Field Painting, and the Washington Color School, she too ventured to create works of pure abstraction. With Red Abstraction Thomas worked with oils, although before long she would turn to acrylic in order to achieve the brightest, boldest, colors.

By this stage in her life, that Thomas's physical mobility were hindered by arthritic pain; so much so, in fact, she usually painted from the confines of her home, often observing the natural world through a kitchen window. The Smithsonian American Art Museum (SAAM) writes, "Thomas began shifting from representation to abstraction in the late 1950s. [...] Red Abstraction represents a moment in this evolution. [Thomas] was inspired by the garden outside her window and painted images that suggest light flickering through leaves and petals. She used dabs and strokes of paint to express the 'new colors through the windowpanes' that appeared every time the plants moved in the wind. [...] Here, the reds, browns, and greens create a warm, heavy mass in the center of the image, which contrasts with the paler shades around the edges. The earthy tones evoke the changing of the leaves during fall, when treetops appear to burst with vibrant color". Thomas herself stated, "Through my impressions of nature, I hoped to impart beauty, joy, love, and peace".

Oil on canvas - Smithsonian American Art Museum, Washington D.C

Resurrection

Resurrection is a square canvas filed with concentric circles made up of individual daubs of bold colors (greens at the center, moving outwards the colors of the rainbow towards a brilliant burst of yellow). The painting marked a pivotal moment in Thomas's career; the point at which she established a footing in abstract art and announced the style for which she would become remembered. Resurrection was created in 1966, just two years after Thomas suffered the arthritic attack that threatened to stop her painting altogether. Art historian William Kloss explains that "inspired by the freedom to paint and the growing recognition she received", Thomas set out to create paintings that were, as she put it, "different from anything I'd ever done. Different from anything I'd ever seen [...] I sat down [in a] red chair here in my living room, and I looked at the window [...] I looked at the tree in the window, and that became my inspiration. [...] So that tree changed my whole career, my whole way of thinking". Indeed, the title Resurrection appears to allude to Thomas's own rebirth as a fully matured artist.

This moment of "enlightenment" gave rise, in fact, to Thomas's famous "Alma's Stripe". As curator Hendrik Folkerts explains, Alma's Stripes are "simultaneously uniform and they have a kind of irregularity as well, so they make an image as a whole, but if you study the stripes in particular, you know they have a life of their own". The balance between uniformity and irregularity in both the dimensions and placement of the marks, lends Resurrection (and, indeed, Thomas's subsequent works) a powerful sense of energy and movement. Says Kloss, "Patterns became her method of organizing colors and building a composition. Patterns are also the source of energy, since the interlinked pattern-blocks vibrate optically. Because of that her paintings are reminiscent of mosaics and their reflective irregular pieces of glass". In 2015, Resurrection became the first artwork by an African-American woman to be acquired by the White House Collection and was proudly hung on the Old Family Dining Room wall by the Obamas.

Acrylic and graphite on canvas - White House Collection, Washington D.C.

Flash of Spring

Thomas was taken by the work of Post-Impressionist Paul Cézanne, and especially his painting Garden at Les Lauves (1906). Cézanne's loosely rendered landscape, comprised of hovering, rectangular strokes of color, was housed at the Phillips Collection in Washington D.C., which Thomas visited frequently. Just as she had found inspiration for her Alma's Stripes in the subtle shifts and glimmers of light she observed from a fixed position through windows offering views of her garden, Cézanne had stated that for Garden at Les Lauves he had explored "the same subject, seen from a different angle" (from his newly-built studio north of Aix) and that "I would occupy myself... for months... by leaning once a little more to the right, once a little more to the left". Flash of Spring represents that which Thomas believed most important in life: beauty and nature. She once stated, "I say everyone on earth should take note of the spring of the year coming back every year, blooming and gorgeous".

The Christie's lot essay for this work states "Its chromatic palette spans the full spectrum of the rainbow; sinuous columns of primary colors in red, yellow, and blue are nestled next to intermediate colors such as orange, green, indigo, and violet. These ribbons of loosely-stacked rectangular strokes rise upward as if part of a living organism, while spreading outward in rainbow-order as if gently swayed by a passing breeze. Beneath the colorful patches of pigment, a luminous white underlayer can be seen peeking through the cracks between each stroke. This imparts a powerful sense of depth that opens up the arrangement and allows it to breathe, creating a subtle sense of movement. In places, Thomas applied extra white pigment to shore up the divisions between the color segments. This key technique enlivens the composition, accentuating its own internal rhythm, which some critics have likened to music. [...] each individual gesture feels effortless and quick, and the bright, joyous colors belie the physical and mental energy required to create such an intricate work".

Oil on canvas board - Private collection

Lunar Rendezvous - Circle of Flowers

As its title indicates, this work was inspired by the first lunar landing. Thomas created several circular compositions shaped by the first images of Earth (from the moon surface). Commenting on this monumental event in human history, curator Alejo Benedetti wrote "everyone is looking to space, looking to the cosmos, and Alma Thomas is aware of that, but she is also saying 'let's take a look back at Earth. [The way] she was applying paint reflected the way in which a gardener places seeds in the group replicated here in these little plantings of staccato paint marks onto the surface of the canvas".

Art history professor Steven Zucker comments, "we have to have an expansive enough view, when we read the title and look at this painting, to be able to hold in our minds both the idea of the garden, but also entire worlds. [It is] atmosphere, it is space, and we are looking at something planetary. Or those are the flagstones of her garden, surrounding a bed of flowers. Or it is two-dimensional paint on canvas". Zucker adds that, although the painting at first appears very flat, its marking allow the viewer to "enter into the interior of a kind of cylinder, or [...] these rings of color begin to move in opposition to each other" creating a spinning sense of energy and movement. Zucker concludes that, although the painting possesses a certain beauty, "it's not an easy beauty. Those colors are tough. There's a deep, almost olive green that's up against a black, that's up against a dull purple, and then there's this brilliant yellow which is up against a sky blue, up against a dull orange. These are not colors that traditionally belong together".

Acrylic on canvas - Crystal Bridges Museum of American Art, Bentonville, Arkansas

Orion

Thomas painted several space-themed works, including A Glimpse of Mars (1969), New Galaxy (1970), Mars Dust (1972), Starry Night with Astronauts (1972), and Celestial Fantasy (1973), inspired by the first lunar landing (in 1969). Orion, composed of densely-packed, all-red Alma's Stripes on a white background, does not reference any actual image from the space mission, but originates rather from Thomas's own imagination, and specifically her ideas about what sorts of scenes one might encounter on a voyage through outer space. Thomas also noticed that "when Apollo was put into orbit, [the comic strip, Peanuts, featured a story where] Charlie Brown left Snoopy spinning around to enjoy the unbelievable". She produced a series of paintings that imagined what the cartoon dog was seeing up there in the great beyond, like Snoopy Gets a Glance at Mars (1969) and Snoopy Sees Earth Wrapped in Sunset (1970).

Art historian Regenia A. Perry states that "the majority of Thomas's Space paintings are large sparkling works with implied movement achieved through floating patterns of broken colors against a white background". The flecks of color interspersed with the white background of the canvas evokes the experience of viewing static-filled and pixelated early images of space (as seen on mid-twentieth-century color television sets). Said Thomas, "I was born in the horse and buggy days, and now experience the phenomenal changes of the 20th century machine and space age. Today not only can our great scientists send astronauts to and from the moon to photograph its surface and bring back samples of rocks and other materials, but through the medium of color television all can actually see and experience the thrill of these adventures. These phenomena set my creativity in motion".

Art critic Elizabeth Hamilton sees Thomas's "Space Series" as contributing to the artistic, musical, and literary field of Afrofuturism, writing that "through sheer imagination, Alma Thomas fantasized about space exploration as a metaphor for Black liberation". She argues that Thomas's "paintings were not just her interpretations of celestial bodies and spaces but also her transformative space to imagine herself in a galactic elsewhere free of white supremacy". Hamilton picks up, in fact, on the similarities between Thomas's statement that "my Space paintings were inspired from the heavens and stars and my idea of what it is like to be an astronaut exploring space" and the views of jazz musician Sun Ra (who is generally credited as pioneering Afrofuturism) who said, "I and my musicians are astronauts. We sail the galaxies through the medium of sound. We take our audience with us where we go whether they want to or not". Says Hamilton, "Afrofuturist art attends to technology, fantasy, reinterpreted pasts, and visions of the future. Both artists wished to travel to space through their art, but only Sun Ra gets heralded as the Afrofuturist prototype. [...] I want to resist this tendency; this is why in my art-history examinations I start with Thomas, who was a radical Afrofuturist who imagined worlds for herself and the children she taught".

Acrylic on canvas - National Museum of Women in the Arts, Washington D.C.

Red Azaleas Singing and Dancing Rock and Roll Music

In the final years of her life, Thomas struggled increasingly with arthritis. As a result, her signature Alma's Stripes became less defined. Her later pieces also tended to be more monochromatic, featuring strokes of a single color against a white background. The titles of these works allude to the fact that she continued to find inspiration in nature (and the flower Red Azaleas) as well as in music, with pieces including Scarlet Sage Dancing a Whirling Dervish (1976), Garden of Blue Flowers Rhapsody (1976), and Red Rambling Rose Spring Song (1976). Also in 1976, she produced her largest-ever work, Red Azaleas Singing and Dancing Rock and Roll Music, comprised of three large panels, across which irregular red marks appear to shimmy across a white background, being more densely packed at the far left, and appearing to break free into empty space at the far right. Art historian Richard J. Powell described this painting as "skillfully negotiating the slippery pathways between nature and society [thereby] epitomize[ing] the integrationist mood of the times".

This monumental work, measuring over thirteen feet long, was created for her last solo exhibition at New York's Martha Jackson Gallery in 1976. Greenberger explains that "although Thomas's works are always striking, even on a modest scale, the artist had a desire to dream bigger. Often considered a member of the Washington Color School, Thomas yearned to work like her colleague Sam Gilliam, whose stained canvases tower over the viewer and often [took] on sculptural qualities. [...] 'I'd like to make [my] canvases bigger, like Sam Gilliam's,' she once said, 'but my arthritis is so bad that I can't get up on my ladder. That wasn't going to stop her from trying, however". When it was unveiled, writes Greenberger, "critics were floored", as was Thomas herself, who reportedly said to one viewer, "Look at it move. That's energy and I'm the one who put it there [...] I transform energy with these old limbs of mine".

Acrylic on canvas - Smithsonian American Art Museum, Washington D.C.

Biography of Alma Thomas

Childhood

Alma Woodsey Thomas was the oldest of four daughters born to businessman and church warden, John Harris, and seamstress, Amelia Cantey Thomas. The dresses her mother made featured beautifully vivid colors. "Everything she made was like a painting", said Thomas. The family lived in the mostly white middle-class Rose Hill neighborhood of Columbus, Georgia. Art historian Regenia A. Perry writes, "Thomas's family was well respected in Columbus, and she and her sisters grew up in comfortable surroundings. The family lived in a large Victorian house high on a hill overlooking the town where Thomas spent her childhood observing the beauty and color of nature". Encouraged by her mother, who was also an amateur violinist, she took music classes.

Thomas and her sisters would spend long summers with their maternal grandfather who lived near the Chattahoochee River in Alabama. She recalled, "He had about a thousand acres there, a marvelous plantation. [...] There were peacocks. In the afternoons we would sit on the front porch while they came and put on their display for us. And there were beautiful pigeons, fantails, and ducks. [...] I would go wandering through the plantation finding the most unusual wild-flowers. And the cotton-oh, that was a gorgeous sight: as far as you could see, beautiful flowers, white with a bit of pink, bell-shaped". Thomas also enjoyed creative activities such as making sculptures out of the red-colored clay she found in the river behind the family home. "I was always building something", she said, and dreamed in fact of being an architect and of building bridges. Thomas later credited her mother and her grandfather with instilling in her a love of art, and her aunts (who were teachers) with instilling in her a love of books and learning.

When she was sixteen, the Thomas family moved from Georgia, where they lived under the cloud of the Atlanta Race Masacre of 1906, to the Logan Circle neighborhood of Washington D.C. Although their social standing suffered a small decline, and while they continued to live under segregation laws, the Thomas' experienced less prejudicial treatment, with the public school system even providing decent educational opportunities for Black girls. Thomas recalled, "At least Washington's libraries were open to Negroes, whereas Columbus excluded Negroes from its only library". Thomas attended Armstrong Technical High School where she joined art classes for the first time. "When I entered the art room, it was like entering heaven. [The school] laid the foundation for my life", she said later. Thomas also excelled in math and science and spoke enthusiastically of her enjoyment of a class on architecture. Indeed, one of the cardboard models she made for that class, of a schoolhouse, was exhibited at the state-run Smithsonian Museum in 1912. Thomas also had some interest in entering a profession such as law but was discouraged from this path as she carried a hearing and speech impediment from birth.

Education and Early Training

After she graduated from high school in 1911, Thomas moved to Miner Normal School (now the University of the District of Columbia) where she studied kindergarten education for two years. In 1914, she worked for four months at the Princess Anne schools on the Eastern Shore of Maryland and, between 1915 and 1921, taught at the Thomas Garrett Settlement House in Wilmington, Delaware. Later in 1921, Thomas enrolled at Howard University. She began a course in the home economics department, with the aim of specializing in costume design. However, Thomas was soon presented with an opportunity to transfer into the University's fine art department. After some hesitancy, she accepted, studying under the department's founder, African-American artist and curator James V. Herring. Thomas said of Herring, "He had beautiful books. He would take the books and explain the artists to me. And so I came to know the great artists".

American artist Romare Bearden and art historian Henry Henderson commented that the paintings Thomas produced at Howard were "academic and undistinguished" and she shifted her primary focus onto sculpture. She graduated in 1924, making her the first woman (of any race) to earn a bachelor's degree in art from Howard. Yet despite this notable achievement, Thomas's first priority was to earn a living wage and she realized that she was unlikely to support herself financially as a professional artist. Thomas duly took up a teaching post at Shaw Junior High School (in Washington D.C.) and remained there (in the very same classroom in fact) until her retirement some thirty-six years later. Thomas once said of her teaching career, "I devoted my life to the children and they loved me". Her great-nephew, Charles Thomas Lewis, observed too that "at one time in Washington, you could say one out of two black people who had gone to the schools in D.C. has taken art from Alma Thomas".

At Shaw, Thomas worked with fellow African-American artist, Malkia Roberts to create a community arts program. The program promoted fine art, marionette performances, and the design of holiday greetings cards (that students gifted to soldiers at the Tuskegee Veterans Administration Medical Center). Thomas took special pride in the fact that, in 1938, she organized the first art galleries to feature in public schools, and secured exhibition space for Black artists at the Howard Gallery of Art. African-American art dealer Thurlow Tibb has called Thomas's time at Shaw her "fermenting period", during which she encountered a number of new influences that informed her art making after 1960. However, while Thomas did dabble with different styles and techniques, she generally preferred to focus her creative energies on watercolor painting.

Thomas furthered her education training while working at Shaw. She attended the Teachers College of Columbia University every summer between 1930-34, earning her master's degree in art education (in 1934) focusing on sculpture and puppetry. She also frequented New York City during her summer vacations, visiting the Metropolitan Museum of Art and other prominent museums and galleries. In the summer of 1935, Thomas undertook more intensive study of marionettes in New York City with German-American puppeteer Tony Sarg (who is still credited as the father of modern puppetry in America). In 1943, Thomas worked with Herring and Alonzo J. Aden (a former student of Herring's at Howard) as co-founders, with Thomas in the role as vice president, of the Barnett-Aden Gallery. It was the first successful Black-owned private art gallery in the United States. Curator Adelyn Dohme Breeskin sees this venture as "'pivotal' in Thomas' development as a professional artist", as it put her into direct contact with leading contemporary American artists who "both challenged and inspired her [and] heighten[ed] her awareness of art trends and directions".

In the late 1940s, Thomas joined up with "The Little Paris Group". Founded by artists and Howard University arts professors, Lois Mailou Jones and Céline Marie Tabary, the group was made up of Black artists from the Washington D.C. including Delilah Williams Pierce and Richard W. Dempsey. They came together twice weekly (on average) for painting sessions with live models. They even established a regular salon in which they discussed current developments in modern art in Paris (hence the Group's name).

In 1950, Thomas took further classes in art history and painting, at the American University, Washington D.C. Her tutors included Robert Franklin Gates, Ben Summerford, and Jacob Kainen (the latter referring to her emphatically as "an artist, not a student"). Over a period of study that spanned a decade, Thomas fostered her growing interest in abstraction and color. Although she was never considered one of its members, that interest coincided with the rise of the Washington Color School. Art historian William Kloss explains that the Washington school painted "abstract shapes of pure color on unprimed canvas which absorbed the brushed or poured paint" (many of the artists associated with the School employed a soak-stain technique whereby thinned acrylic paint was used to saturate the raw canvas). Kloss observes, "there were friendships and mutual admiration between Alma Thomas and these younger [Washington] artists, but she developed mostly apart from their influence. She always primed her canvas and always used a brush".

Mature Period

Art historian Regenia A. Perry notes that "throughout her teaching career [Thomas] painted and exhibited academic still lifes and realistic paintings in group shows of African-American artists. However, while "her paintings were competent, they were never singled out for individual recognition". It wasn't until she finally retired from teaching in 1960, and by now almost seventy years old, that her artistic career took off in earnest.

Thomas had by this time become enthralled with abstraction, dabbling first in Cubism, then "graduating" to Abstract Expressionism and Color Field Painting. Her first works in this style were very large and dominated by blues and browns. Soon, however, she turned to the more vivid colors for which she would become so well-known. Art critic Alex Greenberger writes, "Thomas got to work, effectively recreating the iconic Matisse gouache [The Snail (1952-53)] with a twist. Her version, titled Watusi (Hard Edge) [1963], likewise contains a jumble of rectangles, rhombuses, and squares. Look closely, however, and you realize that Thomas has rotated Matisse's composition 90 degrees. The medium has changed, from gouache to acrylic on canvas, and arguably, the subject matter has changed, too. Judging by Thomas's title, no longer does the work refer to an animal. Now, it may call to mind a dance style popular in the '60s whose name came from the Tutsi people in Africa".

In 1964, Thomas suffered a debilitating arthritic attack. It affected her mobility so severely she feared her artistic career might be over. However, she overcame this setback by producing her famous "Alma's Stripes" technique. Greenberger explains that Alma's Stripes were strokes of acrylic paint, typically with "blank spaces in between them that allow the canvas to peek out [...] Sometimes, these strokes are arranged in vertical lines that cause them to appear like falling leaves or hanging flowers; other times, they are composed in concentric circles". Cultural writer Rosie Lesso observes that the "visually arresting power" of Alma's Stripes speak of a "rich complexity resembling Byzantine mosaics, embroidery, Henri Matisse's early Pointillist art, and the sublime wonder of nature", while Greenberger adds that, "To obtain such a remarkable style [Thomas had also] versed herself in the color theories of Bauhaus artist Johannes Itten".

Greenberger makes the wider observation that, to some critics, Alma's Stripes "seemed out of step" during a period of heightened racial tensions. He writes, "As she was creating her luminous paintings in her own Washington, D.C., home - not in a dedicated studio, but in her kitchen - there were practically protests at her doorstep. She had attended the March on Washington for Jobs and Freedom in 1963 and painted an image of it, but for the most part, her work did little to explicitly portray the tensions of the time and the fight for civil rights".

Towards the end of the decade, Thomas's imagination was sparked by the future possibilities of space travel following the historic first moon landing (in 1969). Commenting on two of her early space-themed paintings, historian Stefanie Graf writes, "These are colorful pictures painted in mosaic technique with the motif of geometric forms. One of these is Blast Off (1970), an impressive, colorful work, which abstractly reproduces the force of the rocket launch. A painting called Apollo 12 Splash Down (1970) [meanwhile] references its landing in the Pacific Ocean". Thomas's space themed pieces would in fact see her linked posthumously to the rise of the Afrofuturism movement. As Kevin Young and Andrew W. Mellon of the Smithsonian's National Museum of African American History and Culture, explain, "In 1993 cultural critic Mark Dery coined the term Afrofuturism. But even before the name Afrofuturism existed, the ideas of Afrofuturism were long present - for African Americans have always reimagined their pasts, sought a better present, and envisioned brighter futures [...] African Americans dreamt of worlds they wished to occupy and soon brought into being".

Now in her eighth decade, Thomas referred to 1972 - the year she became the first Black woman to have a solo exhibition at the Whitney Museum in New York - as her "banner year". In his review of the Whitney show for the New York Times, art critic James R. Mellow called her works "expert abstractions, tachiste in style, faultless in their handling of color", while critic Peter Schjeldahl wrote "She is a gifted, ebullient abstractionist [whose] best pictures are loose, gridlike arrangements of more or less uniform vertical brushstrokes, sumptuous and strongly rhythmic in color and full of light". Not everyone was pleased for her achievement, however. The Black Emergency Cultural Coalition accused the Whitney of "tokenizing" Black art. Thomas was more gracious, however, declaring, "Who would have ever dreamed that somebody like me would make it to the Whitney in New York?".

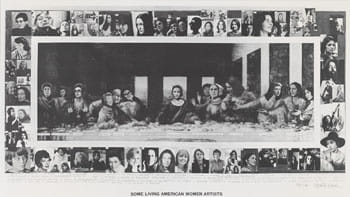

Also in 1972, Washington D.C.'s Corcoran Gallery of Art held a Thomas retrospective. Capping off her good year, Thomas was featured in Mary Beth Edelson's iconic collage, Some Living American Women Artists/Last Supper. Art historian Sharon Patton, meanwhile, described Thomas's Wind and Crepe Myrtle Concerto (1973) painting as "one of the most Minimalist Color-Field paintings ever produced by an African-American artist". Up until her death in 1978, an ailing Thomas continued to produce paintings from the living room and kitchen of her home, often, as artist and puppet maker Schroeder Cherry explains, "propping the canvas on her lap and balancing it against the sofa".

Later Period and Death

Towards the end of her life, Thomas was asked in an interview if she thought of herself as a Black artist. She responded "No, I do not. I am a painter. I am an American. I've been here for at least three or four generations. When I was in the South, that was segregated. When I came to Washington, that was segregated. And New York-that was segregated. But I always thought the reason was ignorance. I thought myself superior and kept on going. Culture is sensitivity to beauty. And a cultured person is the highest stage of the human being. If everybody were cultured we would have no wars or disturbance. There would be peace in the world".

Thomas passed away on February 24, 1978, in Howard University Hospital, following aortal surgery. Her memorial service was held at Howard. The home where she lived for over seventy years, and which she shared with her sister J. Maurice Thomas, is now known as the Alma Thomas House, and is listed on the National Register of Historic Places. Thomas's personal writings were donated by her sister to the Archives of American Art. Shortly before her passing, Thomas told the New York Times that she had "never married a man but my art. What man would have ever appreciated what I was up to?", she said. And while she remained childless herself, Thomas stated "I devoted my time to the children who lived nearby. Rounding my neighborhood were the slums of the world. On Sundays those children would be running up and down the alley. So I got them to clean up and come to my house and we made marionettes and put on plays".

The Legacy of Alma Thomas

Thomas can lay claim to some significant "firsts": the first-ever graduate of Howard University's Art department, and the first woman - of any race - to earn a bachelor's degree in art in the United States. Later in life, she became the first African-American woman to have a solo exhibition at the Whitney Museum of American Art in New York and earned (posthumously) the distinction of being the first female African-American artist to have an artwork enter the White House Collection. At a 2016 reception celebrating the recent renovation of the main White House dining room, First Lady Michelle Obama called her painting Resurrection (1996) "stunning", and explained "I wanted to make sure that other little Black girls growing up would see that they belong in the people's house too, and it's why [...] We placed the painting directly in visitors' line of sight, across from the doorway, and centered right between a pair of towering windows, so that its warmth would greet you the moment you stepped into the room". Her piece, Sky Light (1973), was hung in the Obamas' family quarters.

Thomas also belongs to a select group of artists who have a specific aesthetic feature - "Alma's Stripes" - directly associated with their name. She was also rare amongst her peer group in that she chose to focus on the art of creative expression rather than politicize her art (by directly addressing racial and/or feminist issues). Indeed, art critic Holland Cotter has called her work "forward-looking without being radical; post-racial but also race-conscious", while curator Tiffany E. Barber has stated that Thomas "endeavored to infuse her work with meaning beyond racial and gender constraints. In so doing, she challenged the singularity of race".

Influences and Connections

-

![Paul Cézanne]() Paul Cézanne

Paul Cézanne -

![Henri Matisse]() Henri Matisse

Henri Matisse -

![Joseph Beuys]() Joseph Beuys

Joseph Beuys -

![Yves Klein]() Yves Klein

Yves Klein - Robert Gates

- Jacob Kainen

- James V. Herring

![Sam Gilliam]() Sam Gilliam

Sam Gilliam- Malkia Roberts

- Delilah Williams Pierce

- Richard W. Dempsey

- Endia Beal

- Steven Cushner

![Sam Gilliam]() Sam Gilliam

Sam Gilliam- Malkia Roberts

- Delilah Williams Pierce

- Richard W. Dempsey

Useful Resources on Alma Thomas

- Ablaze with Color: A Story of Painter Alma ThomasBy Jeanne Walker Harvey

- Alma Woodsey Thomas: Painter and EducatorBy Charlotte Etinde-Crompton and Samuel Willard Crompton

- Alma's DreamBy Obiora N. Anekwe

Ask The Art Story AI

Ask The Art Story AI