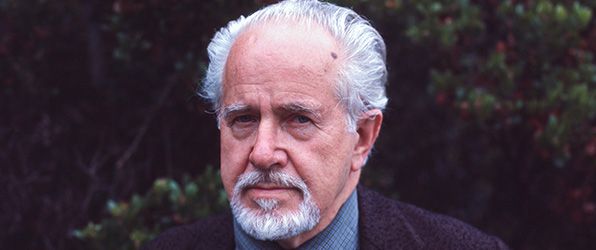

Summary of Mark Tobey

One of the most highly respected American artists of the 1950s and 1960s, Tobey's name is associated first and foremost with his so-called "white writing" paintings; a calligraphic style characterized by a field of intricate and delicate overlapping pale lines. It was a form of gestural abstraction designed to inspire a "higher state of consciousness" in the spectator and it would bring the artist numerous international plaudits and awards. Although in the US Tobey's mindfulness was somewhat "outmuscled" by the action paintings of Jackson Pollock, his push for an "all-over abstraction" gave rise to a spiritual style that amounted to a wholly unique visual language; quite independent of any one international school or location. Indeed, Tobey was a legendary wanderer who travelled through the Americas, Europe and the Far East in search of the influences that would help him refine his highly personalized conception of abstract painting.

Accomplishments

- In 1918 Tobey was introduced to the non-sectarian Baha'i Faith and its idea of universal consciousness. Through its teachings, he developed a way to use meditation as a means of generating abstract shapes and gestures. The result was a distinctive visual language that could articulate a unified conception of life by combining Western art practices with the energy and wisdom of Eastern mysticism.

- Tobey worked largely in water-based media, such as tempera and gouache, and on small-scaled canvases and paper. His all-over abstractions, permeated with a multitude of lines and fragmented forms, captured calligraphic rhythms and gestures that broadened the definition of mid-century American modernism.

- From the very beginnings of his career, Tobey showed a passion for experimentation. Pushing the fixed rules of Cubism, he drew on more animate subject-matter using rich rounded shapes and a wider range of colour. The result was a form of "vitalism" that would push the great modernist experiment to look outside the realms of the physical world or any one of its great religions.

- In later years, Tobey devoted himself to the study of Zen Sumi techniques. By "emptying his mind" of all extraneous thoughts, he found the ideal mental state in which to paint and became positively liberated. By letting "nature take control" over his work, he produced a series of splashed black ink abstractions that demonstrated how art might exist independently of any pre-given aesthetic preferences or ideological influences.

The Life of Mark Tobey

Marking his opposition to Jackson Pollock, Tobey stated "I believe that painting should come through the avenues of meditation rather than the canals of action", and it was only through the meditative act that he felt able to truly "have a conversation with a painting".

Important Art by Mark Tobey

Dem Licht Entgegen (Toward the Light)

Dem Licht Entgegen shows Tobey's early interest in the relationship between painting and spirituality. Although not faith-specific, the painting's title and movement of the people towards the light expresses the theme of religious rapture or spiritual awakening. Three vividly coloured figures - as well as a more ghostly procession that is yet to move into the light - are drawn to a rising sun, blazing over hilltops. Rendered through expressionistic brushwork, the sun casts its rays into the sky and across the landscape where a monumental organic form effloresces in response to its radiance. In this painting, Seattle-based art critic Sheila Farr has noted Tobey's "attraction to the expressionistic brushwork of Van Gogh as well as a bent for spiritual symbolism that would become a hallmark of his mature work".

After a long period of working as a fashion illustrator, creating conventional portraits, landscapes and Cubist-style still lifes, Tobey's contact with American modernists, especially Marsden Hartley, inspired a marked change in direction in his painting. Like many of his contemporaries, Hartley was inspired by Kandinsky's proclamation that, "The mood of nature can be imparted ... only by the artistic rendering of its inner spirit". Following this maxim, Tobey, demonstrating a voracious appetite for experimentation, ventured to convey more organic themes with sensuous, swelling, curvaceous shapes, using thick outlines and an almost arbitrary use of colour. He was exploring here a kind of 'vitalism' in that the origins of life are dependent on a life-force that searches beyond the realms of the physical world. Toward the Light amounts to an expression of Tobey's attraction to the Bahá'í notion that all religions manifest the same light from one God. "When we wake up and see the inner horizon light rising", Tobey said, "then we see beyond the horizon [and] break the mould of men's minds with the spirit of truth. Then there will be greater relativity than before. This light will burn away the mist of life and will become very, very great".

Oil on canvas - University of Arizona Museum of Art

Cirque d'Hiver (Winter Circus)

This pastel drawing, created shortly before Tobey's "white-writing" breakthrough, consists of an intricate, gauzy web of lines that breaks the surface of the picture up into irregular geometric shapes, reminiscent of a shattered car windscreen. It contains intimations of tall spotlights casting a pale blue glow, and what could be the pitched roof of a big top marquee, arching over an arena of frenetic movement and activity, possibly swinging trapeze artists or figures on bicycles.

Cirque d'Hiver is a precursor to the calligraphic style in Tobey's art with the brown, tan and blue tonal quality of the early Cubism of Braque and Picasso. Tobey said, "like the early Cubists I couldn't use much colour at this point as the problems were difficult enough without this additional one [of color]". But, unlike the Cubists, this is not a picture that attempts to present simultaneous views of one subject, it adopts, rather, a more Futurist sense of dynamism and movement, and takes, one step further, Paul Klee's technique of "taking a line for a walk". There is a suggestion too of Tobey's enthusiasm for performance venues, just as New York City's Cotton Club had captured his imagination a decade earlier, in music, and in the visual representation of rhythm.

Pastel on INGRES JAC France laid paper - Seattle Art Museum

Rising Orb

In this study for a mural, reminiscent of a Renaissance fresco, Tobey depicts the commotion stirred in both the human and angelic realms of a new revelation from God into the world, symbolised as a rising sun at dawn. The formal arrangement of the stylised figures, rendered in warm, autumnal tones, is offset against a Cubist deconstruction and flattening of planes. The circling figures, whose rotation breaks up the horizontal geometry, forms a visual echo of the small and barely noticeable sun.

Tobey's acceptance of the Bahá'í teachings in 1918 led to the faith's themes frequently appearing in his work, including the "progressive revelation" of God to humanity, the forces of spirituality versus materialism, the quest to create unity between diverse elements, and the dominance of light over darkness. Tobey would later explain (in 1961) that the woman and man in the left of the painting represent "local time", and the orb that has broken its moorings signifies "solar time".

Tempera and gold paint on cardboard - Seattle Art Museum

Broadway

In his breakthrough into "white writing", married with washes of pale blue, yellow and maroon, Tobey called upon his training in Oriental brushwork with the Chinese painter Teng Baiye to translate his memory and personal experience of the nightlife in New York's "big white way" into a swirling, pulsing calligraphy. The dominant white lines of the image are overlaid on a brown ground which fades to a dark green at the top of the painting. The sheer perspective of the thoroughfare, viewed from a high vantage point, cuts through the middle of the painting, the traffic emerging from a side street at the centre and appearing to move towards the viewer. At the bottom of the painting, the brushstrokes are thick and boldly rendered, suggesting traces of taxi lights, trams or buses. In the lower-left-hand corner, a crowd is gathering outside, or pushing past, a cinema. The lines quite clearly define people, with the only red in the painting highlighting a woman in a coat and hat. White circular lightbulbs are scattered throughout the image, while in the sky, the mesh of marks is less intense, the brushstrokes more spaced out, suggestive of the curves and loops of a Coney Island rollercoaster, or, perhaps, flashing neon signs. On the upper right, finally, there is the evocation of lettered billboards, a pair of eyes, an image of a bottle, and the word "coffee".

Broadway has not yet reached all-over abstraction; the border is roughly painted and irregular, and left raw, acting as a window onto this vibrant, noisy scene. The historian Patricia Junker, in her survey of modernism in the Pacific Northwest, describes this web of white lines as demarcating the "massive force field emanating from human minds and hearts, an aggregate energy so palpable and so powerful that it could almost glow in the dark". For his part, Tobey stated that he had had no conscious plan to create a calligraphic painting. "I've painted Broadway which I must say astonishes me as much as anyone else," he wrote to friends. "Such a feeling of Hell under a lacy design - delicate as a [Jean-Antoine] Watteau in spirit but madness". The fact that Tobey mentioned Watteau, the early eighteenth-century French painter whose works prompted a revival of interest in colour and movement, showed that his knowledge of European art still remained deeply entrenched, which was locked in a struggle for dominance with his latterly acquired Oriental sensibilities.

Tempera on paper board - The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York

Edge of August

The theme of Edge of August existed in Tobey's mind for ten years before he felt able to paint it successfully. Minute, calligraphic marks shimmer like a waterfall through a pale tonal spectrum to evoke the ineffable feeling of transition between summer and fall; perhaps even between East and West, or one era and another. The greenish light of summer fades out into a nearly empty autumn in a potent depiction of the changing seasons. "Edge of August is trying to express the thing that lies between two conditions of nature, summer and fall", said Tobey, "It's trying to capture that transition and make it tangible. Make it sing. You might say it's bringing the intangible into tangible".

While his mature painting has invited comparisons with Jackson Pollock, Tobey's art was anything but "action painting". It was rather a supremely controlled and deliberate approach to painting that asked viewers to immerse themselves in higher dimensions that might exist beyond the physical world. As the art historian Mario Naves observed, "Tobey's art shares pivotal commonalities with Abstract Expressionism [such as] a basis in Surrealism, all-over compositional strategies, and gestural mark-making (albeit on a miniaturist scale)". But, whereas the "chest-thumping verities of The New York School made a noise heard 'round the globe [...] the noise made by Tobey was decidedly more muted". For Naves, this amounted to something of an injustice given Tobey's much greater range and breadth of experience: "He was thirteen years older than Mark Rothko, and Jackson Pollock's senior by twenty-two years [and] had been around the block long before The New York School experienced its triumph. How many Action Painters had experienced the Armory Show of 1913 first-hand [as Tobey had]?" he wondered.

Casein on board - The Museum of Modern Art, New York

Untitled Sumi

Tobey was an artistic alchemist who never settled on a single approach to picture making. In the spring of 1957, he put himself through intensive training in Japanese Sumi techniques, using opaque black ink thrown and splashed in a controlled way onto paper. His teacher, the Zen master Takizaki, told Tobey, "Let nature take over in your work" and he came to the realization that "State of Mind is the first preparation and from this action proceeds". From this teaching came a heightened sense of mental clarity; what Tobey claimed was "perhaps the ideal state to be sought for in the painting and certainly preparatory to the act". Tobey described the creation of the Sumi works, of which he could paint up to 30 in one evening, as "a kind of fever, like the earth in spring or a hurricane [...] I could say I painted the Sumis to experience a heightened sense of living". If he liked the finished work he would sign it, if not, he would just tear up the painting and throw it away.

With his spontaneous Sumi works, Tobey had upended the painstaking deliberation of his white writing. The tradition offered the artist another form of expression that could be brought into the modernist canon. After he had produced more than 100 such paintings, he informed his New York gallery that he wanted "an all black and white show [...] Takizaki here says no one in Japan has done what I have done. I know that Kline exists and Pollock, but I have another note". Art historian Debra Bricker Balken has written, "Tobey may have wanted to investigate the spirited skeins of paint and predominantly black color scheme that Pollock had utilized, through the intermediary of Japanese convention. But action painting was never Tobey's goal, its emphasis on the existential plight of the artist a part of neither his aesthetic approach nor his mind-set".

Seitz had observed that Tobey preferred the Japanese aesthetic to the Chinese, and placed great value the idea of shibui: "that which doesn't look like anything, but in time discloses its jewels". He had embraced the idea of chance and the freedom of the "flung" style, which he employed through his sumi series. Tobey was committed to the "idea that forms could migrate from Orient to Occident just as they previously had in the opposite direction". Indeed, for Tobey, Bahá'í and Zen remained his two most important spiritual influences but, he said, Bahá'í "found him," whereas it was he who sought out and found Zen. "I could never be anything," he finally conceded, "but the occidental I am".

Biography of Mark Tobey

Childhood

Mark Tobey was one of four children born to devout protestants, Emma Cleveland, a seamstress (who referred to Mark, her youngest child, as "the most restless young'un I ever had") and George Tobey, a builder and farmer. Before Mark reached school age, the Tobey Family moved from Centerville, Wisconsin, to land near Jacksonville, Tennessee, where his father planned to build a house and start a sugar cane plantation. However, the lack of educational facilities for their children saw the family return north to Trempealeau, Wisconsin, a village of some 600 inhabitants on the Mississippi River. Tobey recalled an idyllic "barefoot" childhood spent fishing, swimming and playing on the banks of the river: "My whole experience until I was sixteen was just purely nature", he said, "I remember when I saw a water spider and it brought down a bubble of air and placed it over its nest [it was] a magical and fantastic thing".

Tobey's school did not provide art classes but he was often chosen as "blackboard illustrator" for his own and other year grades. According to historian and curator William C. Seitz, both his parents believed in the importance of creative activity. Emma Tobey loved to make "wonderful rugs and things" while George "felt a real responsibility to encourage his younger son's talent". Indeed, Seitz described how Tobey "vividly remember[ed] the rounded forms of animals that George Tobey drew with a thick carpenter's crayon, or carved in Indian red pipestone" adding that George "also bought him tools of art, such as they were", and later, after the Tobey's had moved to Hammond, Indiana, "even sent him twelve miles to a few classes at the Art Institute of Chicago".

The family had moved to the steel-manufacturing town of Hammond in 1906. The voraciously curious Tobey, hitherto completely absorbed by the natural world, became newly captivated by the electric lights and signs, the sheer variety of buildings, and the spirit and diversity of urban life. Resisting his father's idea that he would apprentice as a builder, George paid for him to attend Saturday morning classes in watercolour and oil painting at the Institute between 1906-08. He was forced to abandon his studies when his father became unwell and could no longer afford to fees. However, Tobey fondly recalled his time there, for instance, a teacher's criticism of a landscape he was painting: "You can't have a pink sky in the West, it's too far from the sun" was the somewhat prosaic assessment. Seitz added that, "one professor, 'old Reynolds,' from whom Tobey had a criticism or two, showed real insight when he observed that his student had [already] been infected by 'the American handling bug' - that is to say he preferred flashy brush technique to the tedium of careful modeling".

Early Training

In 1909 the Tobey family moved to inner-city Chicago and, two years later, Mark Tobey took a job as a "blueprint boy" for Northern Steel Works where he learned technical drawing. Having been fired by Northern Steel Works (for a lack of commitment) he was hired as a shipping clerk by Barnes Crosby Engraving Co., and was assigned to the art department where he proved a failure as a letterer and was fired once more. He next found work as a dollar-a-week errand boy for an independent fashion studio. Here, however, Tobey showed off his talent for drawing and his pictures of "pretty girls' faces", which were added to catalogue illustrations, resulting in a six-fold salary increase. Seitz describes how "during lunch hours and after work [Tobey] pored over The Saturday Evening Post and other 'cover girl' publications [becoming] so conversant with the styles of the illustrators that a detail was sufficient for him to recognize their brush mannerisms. His heroes were Harrison Fisher, Howard Chandler Christy, and J. C. Leyendecker who 'for sheer technique took the cake'". Tobey himself recalled that at this stage of his artistic development he was still absolutely certain that "the American girl was the most beautiful thing you could put on canvas".

The Chicago Art Institute had already introduced their young alumnus to "something of monumental light and shade of Raphael and Michelangelo and [of] Titian's color", and the "brilliant brushwork" of Sargent and Frans Hals. Nevertheless, for Tobey it was the great chronicler of the Old American West, Frederic Remington, who, in his words, "flashed like a comet before my eyes". It was only when a senior colleague at the fashion studio encouraged Tobey to be more adventurous by suggesting he "paint something out of your own noodle" that Tobey took a keener interest in the techniques of the great Renaissance masters. But, as Seitz notes, the earliest influence on the "swirling, wavelike rhythms" that would be so characteristic of Tobey's mature works, came when "an elderly Swiss friend, C.A.Schweitzer, took Tobey to a German bookstore where, in the magazines Simplicissimus and Jugend, he saw drawings and paintings by von Stuck, von Lenbach, and Leo Putz". It was these artists who introduced Tobey to the "linear undulations and floriform naturalism of art nouveau".

Mature Period

In 1911 Tobey arrived in New York City where, having been turned down for a post at Pictorial Review, he obtained a freelance position as a fashion illustrator for McCall's magazine. While there he paid for two private classes with the painter, printmaker and teacher, Kenneth Hayes Miller. Between 1912 and 1917 he flitted between New York and Chicago and began to think outside commercial design by starting drawing from life, experimenting particularly with studies of the human figure in motion and at rest. He held his first one-man exhibition of 23 charcoal portraits of well-known figures - including the opera singer, Mary Garden, the French theater director, Jacques Copeau, and the writer and social activist, Muriel Draper - at M. Knoedler & Co., New York, in 1917. He also earned money as an interior designer (which included the "feature" of imitation tapestries) decorating the apartment of Vogue editor Edna Woolman Chase.

Five years earlier (1913) Tobey had attended the International Exhibition of Modern Art in Chicago. The Armory Show, as it was better known, was the first major exhibit of modern art staged in the United States. Tobey was confused by Post-Impressionism in general and specifically by the Cubists. He referred to Marcel Duchamp's Nude Descending a Staircase No.2 as a "chaotic explosion", but his interest in the European avant-garde had been pricked. By 1918, indeed, he had joined an artistic circle that gathered at journalist Walter Arensberg's New York apartment on West Sixty-Seventh Street. The "West Sixty-Seventh group" included Duchamp, Francis Picabia, Man Ray, Charles Demuth, Charles Sheeler, and Marsden Hartley. Tobey's artistic sensibilities became more and more attuned to modern forms of pictorial deconstruction and when he saw Duchamp's Nude Descending five years on, it had transformed in his mind's eye from a "chaotic explosion" into a "wonderful abstraction". The profound challenge for Tobey became henceforward one of form in painting. "The only goal I can definitely remember", he told an interviewer later, "was in 1918 when I said to myself, 'If I don't do anything else in my painting life, I will smash form".

Tobey's portrait exhibition had been organized by Marie Sterner. It was she who introduced Tobey to the portrait painter Juliet Thompson, for whom he agreed to sit. It was during those sittings that Thompson introduced him to the Bahá'í World Faith teachings (introduced into the US in the 1890s) of the oneness of humanity and the unity of all religions. Tobey visited a Bahá'í camp in Maine stating later "I just got it [...] you know, and I said: 'Well, this is the truth.' So that was that". His conversion to Bahá'í had opened Tobey's eyes to the spiritual dimension of life in his art and his sense of being part of a single human race was cemented when he, and his friend Janet Flanner (she would become a well-known writer for The New Yorker) stepped out onto the streets of New York City on Armistice Day (in November 1918). Carried along by the heaving crowds, Tobey felt "completely integrated with the mass spirit". It was his moment of epiphany that would dictate his worldview. Tobey railed against "the Renaissance sense of space and order", stating that pictorial compositions "should be freer and not so separated from the space around them". He added, "I really wanted to smash form, to melt it in a more moving and dynamic way [...] I wanted to smash this image that was in space and I wanted to give the light that was in the form in space a release".

While earning his living painting portraits (including several burlesque and vaudeville dancers) and making caricatures, some of which (including one of Lillian Gish with her hand in her mouth) were published in the New York Times, Tobey continued to experiment with very many art forms and influences. In 1922, following a brief and failed marriage (details of which have remained obscure), Tobey relocated to Seattle where he taught at the Cornish School of Allied Arts, an internationally recognized regional school influenced by the radical educational theory - a non-age-specific teaching method whose key principles were based on Independence of thought and a keen awareness of one's learning environment - of Maria Montessori. The school's founder, Nellie Cornish, recalled her first impression of Tobey as being "a very timid, I would say frightened, young man, and a very uncertain one". The Cornish School provided a studio for Tobey and urged him to be more confident in his painting abilities. It was only now that Tobey belatedly made his "personal discovery of cubism" and the structural animation of space that, according to Seitz, "underlies most of his mature painting" and which allowed him to "see solid objects [...] as transparent and metaphysical".

In time, Tobey gained a reputation in Seattle for being progressive in his teaching methods and for urging his students to trust in their intuitions. He was committed to a receptive method for teaching. Drawing on the attitude of his own mother and father, Tobey advised uncertain parents to "Just give them [children] materials and be interested in art yourselves" while he implored older students to "start with [your] imagination [and] go out and look at things [...] that will stimulate your retentive memory and your retentive memory will bring it back in your imagination again".

In 1923, Tobey struck up a deep friendship with Teng Baiye, a Chinese painter and student at the University of Washington. Tobey set time aside to study Chinese calligraphy with Teng, discovering "that one could experience a tree in dynamic line as well as in mass and light". On one occasion, when Tobey was looking at a goldfish tank, Teng asked him why Western artists painted fish only when they are dead. "Those and a number of other remarks have been a great stimulus to me", recalled Tobey. (Many years later (in 1957), Tobey would ruminate that "if the West Coast had been open to aesthetic influence from Asia, as the East Coast was to Europe [then] what a rich nation [America] would be!".)

It had not been lost on Tobey that while living in New York he had only to "leave Grand Central Station [to experience] the broad sweep of mountains, sea, and forest surrounding the city" whereas "psychologically the only exit from Seattle [...] was toward Alaska". Tobey was in fact influenced by the "carving, weaving, and painting of the Northwest Coast Indians", but in his search for new visual and cultural experiences, Tobey set out on the first of his extended overseas travels throughout Central Europe, the Mediterranean and the Near and Far East. Having visited Barcelona, Greece, Constantinople, Beirut, and undertaken a pilgrimage to the tombs of Baha'u'llah in'Akka and 'Abdul-Baha in Haifa, he spent the summer and autumn of 1926 in Paris. He devoted many hours studying the masterpieces in the Louvre and also attended Gertrude Stein's salon where he further explored the Cubist works of Georges Braque (whom he met) and Pablo Picasso. It was also at Stein's salon that Tobey came into contact with André Masson's Surrealist "automatic writing" technique.

In the fall of 1928, Tobey taught a three-week studio course at Emily Carr's studio in Victoria, Canada. He inspired Carr to explore the means by which forms in nature could be reduced to geometric shapes and thereby evoke spiritual ideas. Carr was, however, ambivalent to Tobey's "clever and beautiful" work; "He knows a lot and talks well", she said, but his work still "lacks something". Upon his return to Seattle, Tobey cofounded the Free and Creative Art School. In 1929, Alfred Barr Jr, director of the recently opened Museum of Modern Art in New York, spotted Tobey's work in Romany Marie's famous Greenwich Village Café Gallery (the catalogue referred to him as a Surrealist) and invited him to take part in the MoMA exhibition Painting and Sculpture by Living Americans. The American modernist Marsden Hartley noted that with Tobey "a new American quality appeared", adding that Tobey "reveals what he has seen and felt, and he has seen clearly, and felt with special gravity the depths of the tides that wash against the barricades of the human spirit. Tobey is a clairvoyant, a revealer of the content of shapes, and he finds a consistent harmonic synthesis for these revelations". In the first major article written on Tobey, meanwhile, Muriel Draper referred to his work as "intellectualized philosophy in paint".

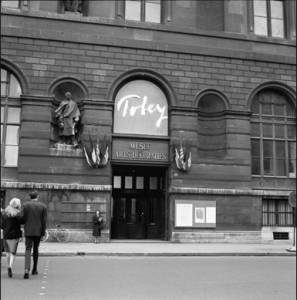

In 1931, Tobey responded to an invitation to teach at Dartington Hall in England, a progressive school and cultural center run by the heiress Dorothy Payne Whitney Straight and her husband, the agronomist Leonard Elmhirst. Dartington was a hotbed of new thinking - attracting writers including Aldous Huxley, Pearl Buck, and Arthur Waley - where Eastern thought combined with modern theories about the relationship of nations and people to each other, to the environment, and to culture. Tobey would become Dartington's most influential and longest serving member of staff, returning there repeatedly from his travels (funded by Straight and Elmhirst) to Mexico, the US and the Orient, over a period of eight years. By all accounts, he was a remarkable teacher. The painter and ceramist Bernard Leach, with whom Tobey enjoyed a lifelong friendship, recalled how he instructed his pupils to "leave your boards - dance! Let go! That's better - dance, you emotionally tied-up English! Now stand up and dance with your chalk on your drawing boards".

In 1934, Tobey and Leach travel together to Hong Kong and Shanghai. Leach went on to Japan, while Tobey remained in Shanghai, living with family and friends of Teng Kuei. Tobey was dazzled by the congestion, the traffic, the dance halls, the night-time buzz and the neon signs of the city, which reminded him of New York. After Shanghai, Tobey retreated to Japan where he was now seduced by its quietness and simplicity. Much of his time in Kyoto was spent practising and watching the sport of archery. He spent a month at a Zen monastery near Kyoto where he practiced meditation and had the time and space to observe tiny events in nature, the effects of water and light on grasses, seeds and lichen. On one occasion, he was given a freely brushed, sumi ink painting of a large circle upon which to meditate. As Seitz stated, the "circle of emptiness" released Tobey from "the domination of others' ideas; and he took as his own the Japanese emphasis on conservation and concentration, simplicity, directness, and profundity".

When Tobey returned to Dartington in the autumn of 1935, his calligraphy studies led to an unexpected development in his painting when he spontaneously created a small work, in tempera on cardboard, made up of a continuous, tangled mesh of white lines. A few nights later, he painted Broadway, translating his memory of New York into a swirling, pulsing calligraphy, expressing his personal experience of the nightlife of the city. His "white writing" style was born, "in gentle Devonshire during the night, when I could hear the horses breathing in the field", he later remembered. "In the process I probably experienced the most extraordinary sensations I have ever had in art, because while one part of me was creating these two works, another part was trying to hold me back. The old and the new were in battle. It may be difficult for one who doesn't paint to visualize the ordeal an artist goes through when his angel of vision is being shifted".

Later Period

In 1938, following a long journey throughout Turkey, and with mounting tensions building towards war in Europe (making it difficult to return to England), Tobey decided to remain in Seattle. During this time, his work became more complex, as he tried to develop his "calligraphic impulse" to capture everything he found seductive about the city. He spent three years studying the people in Pike Place Public Market, producing numerous ink sketches and paintings, that treat the marketplace as a microcosm of humanity. He also devoted himself to music, learning the piano and the flute, studying music theory, and composing his own works.

The art dealer Otto Seligman became Tobey's exclusive representative in Seattle, while he established a significant relationship with the New York gallery owner Marian Willard who affording the artist, who was now pushing his "all-over" painting style to its limits, several exhibitions throughout the 1940s. His 1944 exhibition (at the Willard Gallery) was the first to show his "white writing" paintings and proved a major success. National recognition followed. According to art historians Thomas Williams and Hannah Tuck, Tobey's work revealed to Jackson Pollock "the furthest potential of painting beyond a limiting notion of space, when every inhibition of the 'hole in the wall' had been expunged and when every vestige of representation had been condensed to its synthetic signature on the flat surface of the canvas". In his review of the 1944 exhibition, the infamous New York critic Clement Greenberg had in fact described Tobey as making "one of the few original contributions to contemporary American painting". Yet despite his initial enthusiasm, Greenberg was to conclude that Tobey's painting was "not major. Its mode, which consists in dividing and subdividing within a very narrow compass of sensations, gives the artist too little room in which to vary and amplify", he wrote. In his mission to establish Pollock as the great protagonist of American modernism, Greenberg had effectively deleted Tobey from the narrative of all-over abstraction.

Tobey's temperamental and geographic distance from the "heroic and confrontational" New York School; and the small-scale, overtly spiritual delicacy of his work (not to mention his background in commercial illustration) all counted against him. But contrary to Greenberg's misgivings, Pollock did in fact suggest that Tobey was proof to the lie that New York was "the only place in America where painting (in the real sense) can come thru (sic)". Reviewing Pollock's first show at the Parsons Gallery in early 1948, one writer for Art News even dismissed Pollock's paintings as "[l]ightweight [...] a perverse echo of Tobey's fine white writing" while Tobey himself expressed anger at others riding on the back of his own innovations, saying of Pollock that he just "took my stuff and enlarged it".

Despite his estrangement from the New York School, Tobey's international acclaim grew throughout the 1940s and 1950s. In 1948 he participated for the first time in the Venice Biennale, and the following year in a symposium at the San Francisco Museum of Art with Marcel Duchamp and Frank Lloyd Wright. In 1951, Tobey spent three months as a guest critic of graduate students' work at Yale at the invitation of Josef Albers. His first retrospective show took place at the Whitney and the California Palace of the Legion of Honor in San Francisco.

In Seattle, Tobey was considered the elder of a loose association of artists, identified in a 1953 Life magazine article as the "Mystic Painters of the Northwest". Tobey, Guy Anderson, Kenneth Callahan, and Morris Graves were grouped together as the founders of the "Northwest School", with their collective "mystical feeling toward life and the universe, their awareness of the overwhelming forces of nature and the influence of the Orient". According to the art historian Patricia Junkar, "Tobey's white writing was a revelation to Graves [and had] showed him the way to paint the very spirit of nature". But Graves's appropriation of Tobey's "white writing" led to a cooling of the two men's relationships. "Without my ideas he would be nothing," Tobey said of Graves. "He used to come here night after night ... lie on the floor, ask me to show him my work, and pore over my paintings. Study them [and steal them] Like a thief in the night".

By 1954, the French art critic, Michel Tapie, was singling out Tobey, along with the German painter, Wols, as one of the leading representatives of Art Informel. Meanwhile, Tobey traveled to Basel and Bern in Switzerland. In 1955 Jeanne Bucher, the French gallery owner, gave Tobey his first solo exhibition in Paris. The next year he was elected to the National Institute of Arts and Letters, and he received a Guggenheim International Award. The award coincided with Tobey's new explorations in Sumi ink paintings.

In 1958, Tobey, alongside Mark Rothko, represented the United States of America at the XXIX Venice Biennale where, out of some 3,000 works exhibited that year, his painting Capricorn was awarded, the Premio del Commune di Venezia. Not since James Whistler's Little White Girl - Symphony in White, No.11 triumphed at the first Venice Biennale in 1895, had an American artist won the gold medal. Tobey won the first Art in America award in the same year.

In 1960, having become disillusioned with the politics of the American art scene, and encouraged to do so by the gallery owner Ernest Beyeler, Tobey emigrated, with his companion Pehr Hallsten and secretary Mark Ritter, to Basel, Switzerland. There he lived a near-monastic life but he never ceased working, experimenting constantly with the scale of his paintings and embracing new techniques such as gold leaf, engraving and lithography. The prestigious international exhibitions continued and Tobey was awarded the unprecedented accolade of a solo exhibition at the Louvre's Museum of Decorative Arts in 1961. Prestigious solo presentations followed at The Museum of Modern Art, New York, in 1962, and at the Stedelijk Museum in Amsterdam in 1966. By the end of the 1960s Clement Greenberg had even reversed his opinion on Tobey. As Pop Art and Minimalism superseded Abstract Expressionism, Greenberg was magnanimous enough to concede that, "Tobey wears better and better in general; his truth seems to be enhanced by the contrast with it made by the 'impact' art of the sixties".

Tobey did not return to New York or Seattle after 1970. His health was in decline following a heart attack in 1968 and a subsequent gall bladder operation. He was subject to a major career retrospective at the National Collection of Fine Arts in Washington, D.C., in 1974 but Tobey was not well enough to attend. He would remain in Basel until his death on April 24, 1976.

The Legacy of Mark Tobey

Tobey's art has often been cited as having an influence on Tachisme and Art Informel. But he has informed the practice of an impressively long list of individuals, all of whom have acknowledge a debt to him. He exerted a profound influence on Seattle's "Northwest School" with next generation Northwest artists, like Morris Graves, Kenneth Callahan and Guy Anderson, all acknowledging a deference to Tobey. In New York, the Abstract Expressionist Norman Lewis took much conceptually and aesthetically from Tobey while expressing his own identity with influences drawn from his African American culture. The composer and artist, John Cage, who described him as "our own, an American Picasso", cited Tobey as having a "great effect on my way of seeing, which is to say my involvement with painting, or my involvement with life even".

Meanwhile, Tobey's enduring friendships with Bernard Leach has seen his Bahá'í influences extended to Leach's neighbour in St. Ives, Cornwall, the painter Bryan Wynter. Wynter changed his style radically after seeing Tobey's work in 1956 at London's Tate Gallery. Artist Lyonel Feininger enjoyed a particularly long and creative exchange of ideas with Tobey, stating that he found Tobey's work "breathtakingly expressive and beautiful [that creates a] truly elevated feeling of satisfaction, humility [...] spiritually and formally" while for the Russian sculptor and pioneer of Kinetic Art, Naum Gabo, Tobey's painting was "nearer to music than anyone else's in the field of abstract art". Even after Tobey's passing, his work continued to impact upon pioneering artists. None more so than Keith Haring who, following his arrival in New York in 1978, cited Tobey, Pollock and Klee as the artists who inspired him to elevate his work above subway cartoons to create his bold and distinctive style.

But perhaps the best summing-up of his achievements belongs to Seitz who wrote the following: "In the geography of ideas, he came from nowhere. His speech, mannerisms, and many of his tastes are Midwestern. Much of his subject matter is as Yankee, in its own way, as that of Sheeler, Hopper, or Curry. He is the founding master of the 'Northwest School' of painting. Yet at the same time Tobey may well be the most internationally minded painter of importance in the history of art. What could better illustrate his increasing internationalism than the evolution of his idea of line and brush? It began with the ornamental embellishments of Harrison Fisher and other cover-girl specialists, progressed to Jugendstil and the bravura of Sargent and Sorolla, expanded to include Hals, and finally came to encompass most of the world's calligraphic art, and great Eastern masters like Liang K'ai and Sesshu. What an unprecedented fusion of perspectives!"

Influences and Connections

-

![André Masson]() André Masson

André Masson -

![Wassily Kandinsky]() Wassily Kandinsky

Wassily Kandinsky -

![Paul Klee]() Paul Klee

Paul Klee -

![Jean-Antoine Watteau]() Jean-Antoine Watteau

Jean-Antoine Watteau - Frederic Remington

-

![Marcel Duchamp]() Marcel Duchamp

Marcel Duchamp -

![Francis Picabia]() Francis Picabia

Francis Picabia -

![Man Ray]() Man Ray

Man Ray - Juliet Thompson

- Teng Baiye

-

![Jackson Pollock]() Jackson Pollock

Jackson Pollock -

![Norman Lewis]() Norman Lewis

Norman Lewis -

![Naum Gabo]() Naum Gabo

Naum Gabo -

![Keith Haring]() Keith Haring

Keith Haring - Wilhelmina Barnes-Graham

-

![John Cage]() John Cage

John Cage -

![Mark Rothko]() Mark Rothko

Mark Rothko - Takizaki

- Jeanne Bucher

- Bernard Leach

-

![Abstract Expressionism]() Abstract Expressionism

Abstract Expressionism -

![Art Informel]() Art Informel

Art Informel - Northwest School

Useful Resources on Mark Tobey

- Mark Tobey | Teng BaiyeBy Jo-Anne Birnie Danzker & Scott Lawrimore

- Bachelor Japanists: Japanese Aesthetics & Western MasculinitiesBy Christopher Reed

- Northwest Mythologies: The Interactions of Mark Tobey, Morris Graves, Kenneth Callahan and Guy AndersonBy Sheryl Conkelton & Laura Landau

- Mark Tobey: Art and BeliefOur PickBy Arthur L. Dahl

- Sounds of the Inner Eye: John Cage, Mark Tobey and Morris GravesBy Wulf Hurzogrenrath & Andreas Kruel

- The Artist's Voice: Talks with Seventeen Modern ArtistsBy By Katharine Kuh

- Feininger and Tobey: Years of Friendship 1944-1956By Lyonel Feininger, Mark Tobey, Peter Selz, Achim Moeller

- Mark Tobey: Threading LightOur PickBy Debra Bricken Balken

- Mark Tobey: Tobey or not to be?Our PickBy Jean-Gabriel de Bueil, Véronique Jaeger, Emmanual Jaeger & Stanislas Ract-Madoux

- Mark TobeyOur PickBy Kosme de Barañano & Matthias Bärmann

- The Roundhouse of International SpiritsBy Sebastiano Barassi

- Tobey's 80: A RetrospectiveBy Betty Bowen

- Modernism in the Pacific Northwest: The Mythic and the Mystical - Masterworks from the Seattle Art MuseumBy Patricia Junker

- Mark Tobey: The World of a MarketBy Mark Tobey

- Mark TobeyBy Colette Roberts

- Mark TobeyBy Wieland Schmied

- Mark TobeyBy William C. Sietz

- Mark TobeyBy William C. Seitz

- "Mark Tobey: Threading Light" at the Peggy Guggenheim CollectionBy Mario Naves

Ask The Art Story AI

Ask The Art Story AI