Summary of Robert Hughes

Robert Hughes has been called the "most popular art critic in the country," and to have given Time magazine its "only consistently good writing" in recent years (Seattle Post-Intelligencer, 4/5/93). As an art critic whose heyday has been in the so-called Postmodern era, Hughes has admittedly struggled with living in a new global world where there is no longer a definitive hotbed of artists living in one city, making one great thing after another. Hughes' views on modern art are fairly traditional: he values an artist's formal training more than his instinctual gifts, and he has been highly critical of art that he perceives as ostentatious or self-serving. Overall, Hughes' greatest contribution as a theorist has been to challenge the supposed hubris of Modern artists whose work lacks some greater purpose and exists solely for itself. Key Ideas / Information

- Hughes believes that the art market is necessary and helps many struggling but talented artists to survive. He is highly skeptical, however, of some artists who in his view blatantly pander to the whimsy of the market. In other words, he distrusts artists who are motivated by the tastes of the market and not by their own vision.

- Hughes reveres the great Abstract Expressionists of the '40s and '50s, while at the same time is cautious of bestowing too much praise. Above all, Hughes values an artist's technical prowess and his/her ability to be visually descriptive and earnest, but firmly believes that not all Abstract Expressionists are worthy of the same praise.

- Hughes maintains that great art is a cultural manifestation of sorts, and that particular styles and movements cannot and should not be viewed as separate from their cultural and historical context (i.e. Futurist art must be scrutinized in tandem with Fascism, the political ideology it was fighting against).

Childhood and Early Years

Born to Geoffrey Forrest Hughes and Margaret Eyre Sealy, Hughes was expected from a very early age to grow up and assume a career in law. Both his father and paternal grandfather were prominent lawyers, and his older brother Tom pursued a career in law as well (eventually becoming Attorney General of Australia), but Robert ended up choosing a different path, one that surprised even him. Hughes attended St. Ignatius College in Riverview, Australia, and later attended the University of Sydney where he studied art and architecture. Not being a very committed student, Hughes dropped out of college and took a job as a cartoonist for the Sydney-based periodical The Observer. Soon afterward, Hughes was randomly assigned the role of art critic at the magazine, despite having no real background or formal education in the arts. This was the defining moment in Hughes' early professional life, sparking an interest that would eventually become a career.

While still attending University in the 1950s, Hughes was briefly a member of the left-wing intellectual group called Sydney "Push," which comprised of artists, poets, journalists, philosophers, musicians, lawyers and even career criminals, who typically gathered in pubs to organize large political demonstrations and protests.

In the early '60s, Hughes was one the first contributors to Oz Magazine, a satirical humor magazine based in Sydney, which eventually became known for its subversive and counter-cultural content.

In the early '60s, Hughes was one the first contributors to Oz Magazine, a satirical humor magazine based in Sydney, which eventually became known for its subversive and counter-cultural content. Leaving Australia

In 1964, Hughes left his native Australia for Italy, where he traveled extensively for the better part of a year, before finally settling in London in 1965. While living in England he wrote for The Daily Telegraph, The Nation, The Observer and the London edition of Oz Magazine. While Hughes has described his time in England as less than exciting ("I was having this weird and disastrous marriage .. I was hanging out with a bunch of Australian hippies who were running Oz Magazine.."), he did gain valuable broadcasting experience with the BBC; experience that would become very helpful in the years to come.

In 1966 Hughes published a book entitled The Art of Australia, a detailed history of Australian painting. (Although Hughes was quoted in 2002 as saying, "They could tow Australia out to sea and sink it for all I care," the critic has exhibited a love/hate relationship with his native country, believing that its heritage as a prison colony actually contributed to its role as an insulated home for a few great artists.)

Moves to America

In 1970, Hughes moved to the United States and took a job as chief art critic for Time magazine, a position he held until 2008. Hughes has described his being hired by Time as a "shot in the dark for both them and me." In 1978, Hughes was recruited to become a commentator on ABC's news magazine program 20/20. After only a single taping, Hughes was fired and immediately replaced with a seasoned journalist.

In 1980, the British television network BBC broadcast Hughes' series The Shock of the New, based on Hughes' book of the same name. The educational series was devoted to the development of Modern art since the Impressionist period.

Hughes is the only critic to twice receive the College Art Association's Frank Jewett Mather Award for art journalism, in 1982 and again in 1985. In 1993 he was elected to the American Academy of Arts and Letters.

Later Years

In addition to writing several books in his career, on topics such as the artist Francisco Goya and the history of Australian art, Hughes has been a regular contributor to Time and been a commentator on many American and British television programs. His most notable contribution to American television was the 1997 PBS series American Visions, which traced and critiqued the history of American art and artists since the Revolutionary War. Visions was revered for its impressive breadth of scope, with Hughes covering everything from the early landscapes and Abstract Expressionism to Art Deco and architecture. In 1999, when Hughes was in Australia filming a television series, he was involved in a near-fatal car accident that broke his leg, shattered his elbow, and left him in a coma for several weeks. The next year Hughes was found not guilty by an Australian court for dangerous driving (he was reportedly driving on the wrong side of the road before the accident).

In 2001, Hughes got married for a third time, to the American artist Doris Downes, who is well known for her paintings of botanicals and natural history. Hughes and Downes are still together. That same year, Hughes' 33-year old son Danton, a sculptor, committed suicide in Australia.

In 2006, Hughes published his memoir entitled Things I Didn't Know. The book only covers the first 30 or so years of his life and career, stopping in 1970. Hughes has indicated that a second volume of his memoirs is in the works.

In addition to Time, Hughes has written for The New York Review of Books and The New Republic.

Legacy

Hughes is arguably the only art critic in recent history to have made art criticism necessary again. Other critics in the post-Abstract Expressionist era have adopted a less formal tone, and have praised the avant-garde for being new and provocative without regard for subject matter. Hughes on the other hand has revived a sense of formalism and history when it comes to art. Hughes has taken Harold Rosenberg's idea of a new globalism in art (where movements and styles are no longer found in a single geographical area, like New York or Paris) and critiqued art based solely on its aesthetic value within a global culture. As art movements and styles can no longer be categorized by city or schools of thought, Hughes has strived to educate the art world on what makes for quality art outside the context of the market-dictated value. The biggest example of this is Hughes' outspoken tirades on the work of contemporary British artist Damien Hirst, whose works tend to sell for hundreds of thousands of dollars, and whom Hughes has accused of being "tacky" and "absurd." Other artists whose work has received less-than-favorable attention are Marcel Duchamp, Andy Warhol and Jean-Michel Basquiat.

THEORY SECTION:

Introduction to Robert Hughes' Art Theories

Hughes is probably best known for his strong stance against what he called the "commodification and hyping the market" of the art world in 1980s. The boom in the art market during this time brought Hughes to lambaste many an artist as being overrated and over-hyped, such as Jean-Michel Basquiat. The artworks Hughes admires the most are those than embody a sense of fiction, mystery and history. Specifically, Hughes looks for artists who are unafraid to become deeply personal and even autobiographical with their canvases, to bring something intimate to the work. But no matter how personal something can become, Hughes believes, a memoir in any form will inevitably contain elements of fiction.

Hughes on American art

Hughes believes there is a continuous and cohesive narrative in all of American art, going as far back to its Puritan founders. Being as much an historian as he is critic, Hughes is fascinated with the culture of religion in America (hence his preoccupation with Puritanism), yet he finds a strange paradox at hand: despite America's deep religious roots, Hughes has cited that the country has never produced a formal religious art of any significance. It's because of these deeply-implanted roots, according to Hughes, that America has likewise never produced a truly sensuous painter, its own Matisse in a sense, who possessed what Hughes called an "intelligent sensuousness." Hughes on Art and Money

Hughes has much to say about the emergence of the domineering art market that arose in the 1960s and has only gained in power since. He views the market as both a necessary evil and a constant force for struggling artists to combat just to survive. When it came to Picasso, Hughes stated that he "was a millionaire at forty and that didn't harm him." When it came to Warhol on the other hand, Hughes cited the danger of an artist who clings to the market. Hughes admits to liking Warhol's early works, and gives him credit for being savvy and an instrument of cultural change, for somehow presaging the effects of mass media and capitalizing on it. What bothers Hughes is that Warhol became "exceedingly trivial" and exploitative of the art world. Hughes indicates that when people pay millions of dollars at auction for a Warhol, this is the worst of both worlds: both Warhol and the art market exploited one another for mutual gains, but instead of discerning art lovers recognizing this historical gaffe, people end up paying thousands for something he scribbled on a cocktail napkin, because the art market has unapologetically fetishized Warhol's work.

Hughes has much to say about the emergence of the domineering art market that arose in the 1960s and has only gained in power since. He views the market as both a necessary evil and a constant force for struggling artists to combat just to survive. When it came to Picasso, Hughes stated that he "was a millionaire at forty and that didn't harm him." When it came to Warhol on the other hand, Hughes cited the danger of an artist who clings to the market. Hughes admits to liking Warhol's early works, and gives him credit for being savvy and an instrument of cultural change, for somehow presaging the effects of mass media and capitalizing on it. What bothers Hughes is that Warhol became "exceedingly trivial" and exploitative of the art world. Hughes indicates that when people pay millions of dollars at auction for a Warhol, this is the worst of both worlds: both Warhol and the art market exploited one another for mutual gains, but instead of discerning art lovers recognizing this historical gaffe, people end up paying thousands for something he scribbled on a cocktail napkin, because the art market has unapologetically fetishized Warhol's work. Hughes wrote for The New York Review of Books in 1984, "There is no historical precedent for the price structure of art in the late twentieth century. Never before have the visual arts been the subject - beneficiary or victim, whatever your view of the matter - of such extreme inflation and fetishization."

Hughes on the Work of Willem de Kooning

In a 1984 review for the Willem de Kooning retrospective at the Whitney Museum, Hughes reminded readers that de Kooning was in fact a highly trained and learned artist. Hughes wrote that "he brought with him something that very few of his colleagues in the New York School of the forties and fifties would turn out to have: a thorough, guild-based art training that centered on formal drawing of the figure." This review was possibly an attempt on the part of the critic to distance himself from Harold Rosenberg's ideology of "Action Painting," which Hughes believed unfairly pigeonholed the Abstract Expressionist style. Hughes revels in the challenge of peering into de Kooning's paintings and tracing the history of what inspired the artist, of identifying the subtle painterly elements that others may have missed. "Their inherent structure had nothing to do with German or any other kind of modernist Expressionism," Hughes wrote about de Kooning's more ambitious abstracts. "It was closer to Cubism, but with the turning and flickering of Cubist shape given a jostling density, almost literally made flesh.." According to Hughes, de Kooning is an artist with finely-tuned classical and modern instincts. The artist's greatest paintings (Hughes cites Attic, Excavation and Gotham News among them) are rich in narrative and visually descriptive, which in the annals of art history makes them timeless.

Hughes on the "Death" of Abstract Expressionism

In a New York Review of Books article in 1978, Hughes pin-pointed the end of Abstract Expressionism alongside the suicide of Mark Rothko. But it wasn't the artist's death itself that symbolized the end of an era; it was the ensuing aftermath of his death that caused Hughes to look back on the dramatic changes in the art world since the '40s and '50s. After Rothko's death, the artist's children sued the trustees of his estate for allegedly selling Rothko paintings at far less their true market value. Four years of high-profile hearings and litigation followed in what eventually became known as the "Rothko Case," finally ending with a victory for the Rothko children. This obsession with market value is what bothered Hughes the most. "There is no agreement in the American art world on how critics, museum curators or dealers should behave," wrote Hughes. "In the 1950s, if a critic such as, say, Thomas B. Hess owned not one or two but a dozen paintings by Willem de Kooning and wrote lyrically in support of his work .. nobody minded; it was assumed that since the works were worth only a thousand to a few thousand dollars apiece, their value could have no bearing, not even a subliminal influence, on a man's opinions of their worth." However, as the market grew more and more powerful in dictating a painting's monetary value, new expectations were established for how an art critic should behave; it would now be unethical for a critic who owns a high-priced work of art to praise the artist who made it, for it might appear that he was trying to increase its market value. Hughes believes that when the art market became the art world at large, and dictated its politics, certain freedoms of expression died, Abstract Expressionism along with it.

Writing Style

Hughes is an extremely discerning critic who doesn't judge artistic movements or even individual artists so much as he judges individual works of art. When tackling the subject of an artist's lifework or a museum exhibition, Hughes attempts to write with and look for art that possesses what he calls a "Whitman-esque sensibility" (referencing the writer/poet/journalist Walt Whitman). By this he means the ability to take in everything around you, "to breathe in, not out." Hughes tends to write in the style of a novelist. He considers his primary goal in writing about art the very same as the artist who paints: to tell a story, complete with detail, narrative layers, and perspective.

ARTISTIC INFLUENCES

Below are Robert Hughes's major influences, and the people and ideas that he influenced in turn.

ARTISTS

Francisco Goya

Georgia O'Keeffe

Isamu Noguchi

Willem De Kooning

Robert Rauschenberg

CRITICS/FRIENDS

Walter Benjamin

Tristan Tzara

George Orwell

Harold Rosenberg

Alan Moorehead

MOVEMENTS

Futurism

Dada

Surrealism

Cubism

Abstract Expressionism

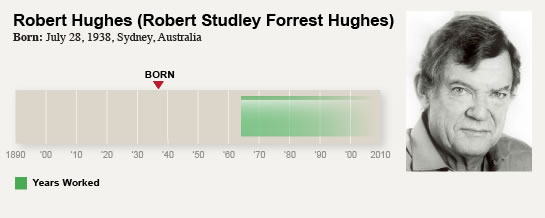

Years Worked: 1964 - present

ARTISTS

Robert Rauschenberg

Richard Long

Sol LeWitt

CRITICS/FRIENDS

Clive James

Germaine Greer

Barbara Rose

MOVEMENTS

Conceptualism

Neo-Expressionism

Quotes

"You have to be a bit vulgar to be a great painter." "All art is fiction, and the more complex the fiction, the better the art is apt to be."

"A Gustave Courbet portrait of a trout has more death in it than Rubens could get in a whole Crucifixion."

"Popular in our time, unpopular in his. So runs the stereotype of rejected genius."

"The new job of art is to sit on the wall and get more expensive."

"I am often viewed as a 'conservative' critic. On the other hand, what does 'conservative' and what does 'radical' mean in today's context? As far as I can make up, when an artist says that I am conservative, it means that I haven't praised him recently."

"I have always tended to take art contextually. If I have any merits as a critic, they have to do with my ability as a storyteller .. and above all I wanted to tell a story."

"The greater the artist, the greater the doubt. Perfect confidence is granted to the less talented as a consolation prize."

Content written by:

Justin Wolf

Justin Wolf

THIS PAGE IS OLD

The Art Story Foundation continues to improve the content on this website. This page was written over 4 years ago, when we didn't have the more stringent/detailed editorial process that we do now. Please stay tuned as we continue to update existing pages (and build new ones). Thank you for your patronage!

IMPORTANT ARTWORKS:

|  |  |

|  |

| FEATURED BOOKS: Written by Hughes  Goya Goya  Nothing if Not Critical Nothing if Not Critical Selected Essays on Art and Artists  The Shock of the New The Shock of the New The Hundred-year History of Modern Art, Its Rise, Its Dazzling Achievement, Its Fall  American Visions: The Epic History of Art in America American Visions: The Epic History of Art in America  The Fatal Shore: The Epic of Australia's Founding The Fatal Shore: The Epic of Australia's Founding  Culture of Complaint: The Fraying of America Culture of Complaint: The Fraying of America  Barcelona Barcelona  Things I Didn't Know Things I Didn't Know RESOURCES: Films by Hughes  American Visions: The History of American Art and Architecture American Visions: The History of American Art and Architecture PBS series, 1997  The Shock of the New The Shock of the New Eight part series on the rise and fall of the modern art movement, 1982 Articles and Speeches by Hughes  Pablo Picasso Pablo Picasso Time Magazine June 8, 1998  Day of the Dead Day of the Dead The Guardian September 13, 2008 Articles about Hughes  Robert Hughes's Amerika $ Robert Hughes's Amerika $ The New Criterion June, 1997  Robert Hughes Discusses 'Goya' Robert Hughes Discusses 'Goya' The Washington Post November 14, 2003  Critical Overload Critical Overload The Observer December 24, 2006  The Upside-Down Critic The Upside-Down Critic Slate.com January 19, 2007  Hirst Hits Back at Aussie Critic Hirst Hits Back at Aussie Critic The Sunday Morning Herald September 9, 2008  Germaine Greer Note to Robert Hughes: Bob, dear, Damien Hirst is just one of many artists you don't get Germaine Greer Note to Robert Hughes: Bob, dear, Damien Hirst is just one of many artists you don't get The Guardian September 22, 2008  Robert Hughes: A Refreshingly Frank Comment on the Art Market Robert Hughes: A Refreshingly Frank Comment on the Art Market World Socialist Web Site October 14, 2008 Interviews  PBS interview PBS interview The Fatal Shore and Australia September 5, 2000  The Critics, part 5 - Robert Hughes The Critics, part 5 - Robert Hughes Sunday Morning November 20, 2005 Documentaries and Short Video Clips  Interview on CBS's 60 Minutes Interview on CBS's 60 Minutes December 28, 1997  Trouble in Utopia Trouble in Utopia  Business of Art Business of Art  Shock of the New (excerpt) Shock of the New (excerpt) Hughes comments on an unusual work of 19th-century French architecture  Shock of the New (excerpt) Shock of the New (excerpt) Hughes comments on Marcel Duchamp  Robert Hughes: The Business of Art - A comical interaction with a collector Robert Hughes: The Business of Art - A comical interaction with a collector In Pop Culture  The Shock of the New The Shock of the New Documentary film narrated by Robert Hughes  Crumb Crumb Commentator on 1994 documentary film  Robert Hughes' IMDB.com profile and list of credits Robert Hughes' IMDB.com profile and list of credits |