Summary of American Art

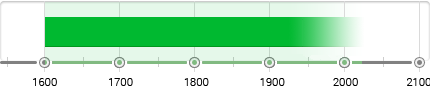

The United States' rich artistic history stretches from the earliest indigenous cultures to the more recent globalization of contemporary art. Centuries before the first European colonizers, Native American peoples had crafted ritual and utilitarian objects that reflected the natural environment and their beliefs. After the arrival of Europeans, artists looked to European tendencies in portraiture and landscape painting to craft representations of the new land, but it was not until the middle of the 19th century with the Hudson River School that American artists were considered to have launched a cohesive movement. Through the early 20th century, artists still took cues from European avant-garde groups but increasingly focused on the denizens of American urban centers and the more rural Midwest. After World War II, the artists that comprised the Abstract Expressionist movement found international fame and notoriety, and for the first time, American artistic influence moved abroad, and later Minimalism and Pop Art greatly impacted the art world. Subsequently, with various global art centers and international connections, it is now more difficult to point to a specific American art trend, although one can still chart the influence of American artists in the global art sphere.

Key Ideas & Accomplishments

- While not originally recognized by the European colonizers, the artistic creations of the indigenous Native American tribes were varied and long held. Abounding in various media and styles, Native American art encompassed the decorative, utilitarian, and ritualistic. Incorporating European styles and materials in the 19th century, Native American artists transformed traditional subjects and processes to tell their stories and continue to do so today.

- As the United States' territory grew through the 19th century due to the annexation of land, both painting and photography propelled manifest destiny's ideas of American exceptionalism and romantic notions of national identity. Large landscape paintings depicting the American West captured the sublimity of the natural landscape, and photography in particular was instrumental in some cases in the creation of National Parks.

- For many art historians, the designation "American Art" usually ended at World War II. After the international recognition of Abstract Expressionism, the art world became increasingly globalized and diffuse, with styles and trends practiced in all corners of the world, but recent scholarship has focused on the transnational dialogues that are occurring now and tracing those back to create a richer understanding of the art of the United States.

The Important Artists and Works of American Art

A Wild Scene

This dramatic landscape exemplifies the work of the Hudson River School. A stunning vista of rocky outcrops and precipitous mountains opens upon a waterfall, in the center right, breaking into a luminous pool that flows into the ocean on the left. A craggy ancient tree frames the right border, its twisted limbs curving vertically toward the darkly portentous sky. Native American figures, dressed in animal hides and armed with bows, occupy the lower third of the canvas, one outlined against the pink and blue patch of sky on the left, the others located beneath the two prominent trees. As art historians Elizabeth Mankin Kornhauser and Tim Baring wrote, the work is "a fine essay in the sublime: the rough, uncultivated landscape and dark, rolling clouds...convincingly represents an untamed wilderness." Precise detail reflects the influence of Naturalism, while what the artist described as its "flashing chiaroscuro and a spirit of motion pervading the scene, as though nature was just waking from chaos," reflects a Romanticist inspiration.

Art historian Carl Pfluger wrote that Cole "virtually invented a new style of landscape, specializing in views of the wilderness." The artist described the painting as "a vision of the earliest form of society, the 'perfect state' of nature, with appropriate savage figures." The portrayal of Native Americans and the description of them as "savage" played into the growing mythology of uncultured peoples who on one hand added something like authenticity to the landscape but on the other were not "civilized" enough and had to be removed as settlers moved West during the era of Manifest Destiny. Cole and the Hudson River School significantly influenced American environmental movements, as well as new art directions, including American Regionalism and Group f/64. Contemporary artists Charles LeDray, Stephen Hannock, and Angie Keifer have repurposed Cole's works, as seen in LeDray's Empire (2015).

Oil on canvas - Baltimore Museum of Art, Baltimore, Maryland

Cliff Dwellers

Bellows' Cliff Dwellers, with its depiction of the gritty vitality of slum life, exemplifies the Ashcan School. In a neighborhood of tenement buildings, its denizens crowd into the streets, engaged in a variety of activities; some women and children sit on the steps, a mother admonishes her child at center, while working men and a street vendor throng in the background. Only a touch of horizon and sky remains between the vertical rows of apartments and the network of clotheslines that diagonally cross the street from building to building. As the people gather outside to avoid the heat in the stifling apartments, the brushwork, vibrant and vigorous, creates a sense of physicality. Apartment dwellers can be glimpsed in the upper levels of the buildings, as they seem to be caught up in private conversations or lean out of their apartment windows. The work reflects the impact of immigration in the era, as recent arrivals were densely crowded into slum neighborhoods. Yet as art critic Michael Kimmelman writes, "the joylessness of the subject is undercut by the soft light that streams into the scene and by the characters on the stoops and in the streets whom Bellows endows with more charm than misery."

Part of the second generation of the Ashcan School, Bellows used the group's then favored strategies in this work, employing a geometric compositional scheme as well as the "chords," or triads of complementary colors expounded by Hardesty G. Maratta's color theory. Yet, his fluid brushwork and vibrant color made his work distinctive, as he conveyed the robust swagger and energy of working class life.

Oil on canvas - Los Angeles County Museum of Art

The Steerage

This photograph has become famous both as a cultural document of immigration to America and as a pioneering work of American modernism and Straight Photography. The image is cropped to emphasize the diagonals of the gangplank horizontally crossing the frame while intersecting the massive column on the left, echoed by the stairway on the right intersecting the horizontal planes of the upper deck. The upper level, reserved for the well-to-do, seems peopled primarily by men, the shape of their hats catching the light as they look down into the steerage, where women and children, along with clothing hanging up at the left, create a sense of a lived-in space like a crowded tenement. Though the work highlights class and gender divisions, Stieglitz was primarily interested in its formal qualities, as its sharp focus converged on intersecting planes, shapes, and angles.

Around 1900 Stieglitz began using large format cameras and considered this his first truly "modernist" picture, as he said, "Intensely direct. Not a trace of hand work on either negative or prints. No diffused focus. Just the straight goods." He published the photo in Camera Work in 1911 along with several of his other photographs.

Photogravure - The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York

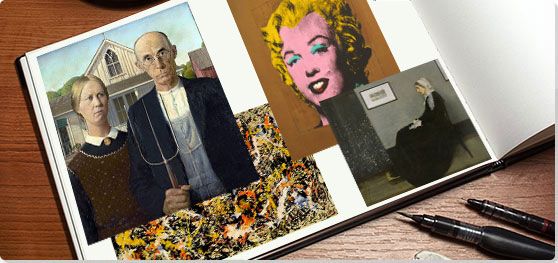

American Gothic

Exemplifying American Regionalism, this iconic image depicts a dour couple in a frontal pose, reminiscent of folk art portraits, in front of their American Gothic Revival-style farmhouse. The man, aloof but confrontational, grips an upright pitchfork, while gazing directly at the viewer, while the woman's slight turn toward him conveys a hint of deference, as she stares into the distance with downturned brows and lips. The vertical lines of the pitchfork rising to the lightning rod on the roof and echoed in the fabric of the man's shirt and the house's paneling emphasize the stasis and rigidity of the figures. Influenced by Hans Memling, a 15th-century German artist, Wood employed a grid-like structure, echoing patterns, and precise detail to create the instantly recognizable portrait.

Yet for all of its apparent clarity and accessibility, the work has aroused much debate, over the identity and relationship of the couple and the artist's intention. Wood based the portraits on his dentist and his younger sister, but many viewers took the two for husband and wife. As art critic Dennis Kardon noted, "One is struck by the incredibly subtle details, cues, and complex formal structure that undermine any simple reading." When the work was first shown at the Art Institute of Chicago's 1930 annual exhibition, some debated whether the portrayal was ironic or meant to be, as Woods insisted, a celebration of the Iowa he loved. The work was also widely featured in national newspapers as embodying a new American art that portrayed hard-working American farmers. Subsequently, the image has been parodied in countless magazines, advertisements, videos, films, and TV series, making it among the most recognizable of American artworks.

Oil on Beaver Board - The Art Institute of Chicago

Migrant Mother

This iconic photograph depicts Florence Owen Thompson, a migrant mother with three of her seven children, at a pea pickers camp in California. Due to freezing rains, the crop had been destroyed, leaving the pea pickers out of work, and many of them faced starvation. Her face creased with worry, she looks into the distance as if contemplating a harsh and bleak future of poverty and grinding work. Her two young children on either side of her turn away from the camera, as if leaning into her for comfort and shelter, while an infant swaddled in worn blankets rests in her lap. In the 1930s, the image evoked a kind of modern Madonna and Child but viewed within Social Realism's unflinching look at the plight of workers.

Lange took this photograph for the Farm Security Administration program, a program that both provided aid to farmers effected by the Dust Bowl and Great Depression and supported the work of photographers to document the human cost. Lange described the occasion in her notes, "I did not ask her name or her history. She told me her age, that she was 32. She said that [she and her children] had been living on frozen vegetables from the surrounding fields, and birds that the children killed. She had just sold the tires from her car to buy food." Taking a number of photographs of the mother and her children in their make shift shelter, Lange, felt this one was the most powerful image, due to its composition and its close-up focus on the mother. Almost immediately, the photograph was widely published throughout the United States and became the iconic image of the era, and today remains one of the most recognizable photographic images of all time.

Gelatin silver print - The Museum of Modern Art, New York

The Migration of the Negro, Panel 3

This painting depicts one of the sixty panels in the artist's Great Migration series, a signature work of the Harlem Renaissance. Depicted as elemental forms in flat planes of color, a group of African Americans, carrying their possessions, form a pyramidal shape that conveys their collective purpose and unified strength. Pressing horizontally forward, they also rise up, outlined against a barren hill, as a curving line of crows both echoes their flight and evokes a sense of danger escaped. Each of the works in the series had a caption, and this one reads "From every Southern town migrants left by the hundreds to travel north."

Influenced by Mexican muralist José Clemente Orozco, Lawrence saw these small works, each 12 by 18 inches, as a single work, in effect, a mural but innovatively divided into parts. He worked on all sixty panels simultaneously. The panels also resemble film storyboards, and as art historian Elsa Smithgall noted, "He thought very carefully about the progression from one image to another," using "syncopated refrains that remind us of the backdrop of jazz." Calling his synthesis of broad color planes and flat linear design, "dynamic cubism," Lawrence was also, and primarily, influenced by his own childhood and the colors and shapes of Harlem. He studied with painter Charles Alston and, later, sculptor Augusta Savage, and as art historian Leslie King-Hammond noted, was the "first major artist of the 20th-century who was technically trained and artistically educated within the art community in Harlem."

Fortune magazine featured Lawrence's series after its exhibition, and the Museum of Modern Art and The Phillips Collection purchased the work and divided the 60 panels between them. Lawrence's work later influenced Kerry James Marshall, Faith Ringgold, Robert Colescott, Hank Willis Thomas, and Alexis Gideon

Tempera on gesso on composition board - The Phillips Collection, Washington DC

Autumn Rhythm No. 30

This work exemplifies Abstract Expressionism and what Harold Rosenberg defined as Action Painting. The "drip" painting, with its energetic swirling web of black, brown, and white lines, embodies a vortex of movement, as intense gestures verge toward chaos while unified and controlled by a sense of rhythm. The scale of the work at 8 by 17 feet creates a monumental effect, overwhelming and enveloping the viewer, and lacking a central focal point or hierarchal composition, every inch of the surface becomes equally significant.

Pollock placed the unstretched canvas on his studio floor and used trowels, sticks, and paint poured directly from the can; he moved around the work's edges as he dribbled, flicked, spattered, poured, and flung pigment. He remarked to an interviewer, "When I am in my painting, I'm not aware of what I'm doing...the painting has a life of its own. I try to let it come through."

Pollock created his first "drip" painting in 1947, which his wife, the artist Lee Krasner described, "seemed like monumental drawing, or maybe painting with the immediacy of drawing - some new category." Allan Kaprow recognized this "new category" in his 1958 essay "The Legacy of Jackson Pollock" where he argued that Pollock took painting as far as it could go, and now artists had to leave the canvas all together. A host of artists, including Richard Serra, Bruce Nauman, Carl Andre, Robert Morris, Eva Hesse, and Claes Oldenburg, went beyond painting in Happenings, Minimalism, and Post-Minimalism to explore the implications of the pioneering Abstract Expressionist's work.

Enamel on canvas - The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York

Gold Marilyn Monroe

This signature work of Pop Art depicts an image of Marilyn Monroe, centered within a gold background, that suggests a Byzantine religious icon. The black and white publicity photo that the artist used was taken from the hit film Niagara (1953) where Monroe, having developed her signature make-up look, played the femme fatale who met a tragic end. The film noir was famous for its nearly nude scenes of the actress and its 30-second long filming of her walking away down the street, in slow motion with her hips swaying. Here, a garish color palette has transformed the photo, though its underlying black and white creates a sense of emerging darkness. By portraying her as an icon, Warhol subtly critiques the modern cult of celebrity, as well as suggesting that it was this depersonalization that drove the tragedy. While the surface is gold and shiny, the space she inhabits is empty. At the same time, only her disembodied head is depicted, suggesting a lack of agency and empowerment, leaving her to be the object of a gaze.

In August 1962, the superstar Marilyn Monroe died from an overdose of sleeping pills, and the world became obsessed with her life, her film career, her celebrity as a "sex goddess," and the tragedy that both occurred throughout her life and led to her death. Warhol made a series of works from this image, reproducing it again and again, just as it was reproduced in magazines and newspapers, evoking the superstar as a brand, another item on the shelf of consumer culture. Warhol's Diptych (1962), another work in his Marilyn series, was named by a survey of 500 artists and critics as the third "most influential piece of modern art," in 2004.

Silkscreen - The Museum of Modern Art, New York

Spiral Jetty

This famous Earth Work is a counter clockwise, 1500-foot long spiral that extends into the Great Salt Lake in Utah, replicating the growth patterns of crystals and seashells. Smithson chose the northeastern section of the lake because the environment had been negatively impacted when the Southern Pacific Railroad cut off the influx of fresh water into the lake in 1959, resulting in an explosion of Dunaliella salina, saltwater tolerant red algae. He found the resulting red and violet hues evoked a dystopian landscape and felt that the piece would draw attention to how human action could both ruin and transform the environment.

Shaped out of mud, crystalized salt, and black basalt, the shape has taken on the crystallization and coloration of changing conditions, but for many years remained completely submerged underwater. Spiral Jetty embodies the artist's emphasis on the concept of entropy, or the devolution of systems over time. At the same time, the shape evokes a primal symbol, often replicated on ancient cave walls and stones within many cultural contexts. As art critic Jonathan Jones noted, "When Smithson built Spiral Jetty, he reinvented the stone age. Its mysterious marking of the landscape deliberately resembles the prehistoric architecture of neolithic Britain...has forebears in the Americas, from the Nazca lines of Peru to...Serpent Mound... This neo-primitivism lives on in art, from James Turrell's continuing bid to turn Roden Crater in Arizona into an astral observatory (or temple) to Olafur Eliasson's current efforts to place 12 huge lumps of Arctic ice in the heart of Paris."

Mud, precipitated salt crystals, rocks, water coil - Rozel Point, Great Salt Lake, Utah

Gay Liberation

This life-sized work depicts a gay couple and a lesbian couple in intimate conversation. One man has his arm around the shoulder of the other, as he turns toward him as if listening attentively. While holding hands and turned toward one another in conversation, the two women relax on a park bench. The work creates a sense of comfortable privacy within a public space, here in the triangular park in Greenwich Village. The sculpture commemorates the events that followed a New York police raid on the gay bar Stonewall Inn in the summer of 1969. The Stonewall protests that erupted became a primary impetus for the Gay Pride movement.

Segal created his sculptures by using orthopedic bandages dipped in plaster that he then applied to living models. He then placed the cast figures, usually in small groups, in an ordinary setting as if at a lunch table or in a train station. Though part of the Pop Art movement, unlike most of the Pop artists he explored existentialist themes and the psychology of the underlying human condition. As a result by the early 1980s he had begun creating memorial works like this one, followed by The Holocaust (1982) and Depression Bread Line (1991).

Though the work was commissioned in 1972, due to controversy, it wasn't installed until 1992. Anti-gay critics were offended by the celebration of gay couples or by the public display of affection. Those who had participated in the Stonewall protests felt the work's two Caucasian couples failed to represent the diversity of the gay community that led the movement. As a result, the work has continued to be a flashpoint of Queer art, often repurposed or reimagined by contemporary artists.

Bronze, steel, white lacquer - Christopher Park, New York

I shop therefore I am

In this famous Feminist and Conceptual piece, Kruger combines text and a magazine image, creating what art critic Ron Rosenbaum described as "formal verbal defacements of glossy magazine pages, glamorous graffiti." The phrase refers to stereotyped media portrayals of women who seem to live for shopping, while the masculine hand, displaying the phrase like an ad markup, reflects how those advertising campaigns are primarily created by men and based upon their assumptions. The work's use of color makes the slogan more direct, powerfully contrasting with the grainy black and white of the background image, as it rephrases the famous statement of the French philosopher René Descartes, "I think, therefore I am." As Rosenbaum noted, "She has appropriated this statement to fit the idea of material consumption," creating an effect of "short machine-gun bursts of words that when isolated, and framed by Kruger's gaze, linger in your mind, forcing you to think twice, thrice about clichés and catchphrases, introducing ironies into cultural idioms and the conventional wisdom they embed in our brains."

Kruger first worked as a page designer for Mademoiselle magazine then went on to work in other high-level graphic design and advertising jobs, where as Rosenbaum described, "She turned out to be a master at using type seductively to frame and foreground the image and lure the reader to the text." Leaving the field, she employed those same strategies to challenge social assumptions, saying, "Although my art work was heavily informed by my design work on a formal and visual level, as regards meaning and content the two practices parted ways." Favoring a direct and powerful approach, she said, "to deal with the complexities of power and social life... as far as the visual presentation goes I purposely avoid a high degree of difficulty."

Photographic Silkscreen/Vinyl

Napoleon Leading the Army Over the Alps

This large equestrian portrait depicts a contemporary African-American man riding a rearing white steed, in an appropriation and re-visioning of Jacques-Louis David's famous Bonaparte Crossing the Grand Saint-Bernard Pass, 20 May 1800.

The young man wears camouflage army fatigues, a white bandanna, and red sweatbands, as a gold cloak swirls and flows around his shoulders, echoing the gesture of his tattooed arm pointing upward and onward. On the rocky path, stones are inscribed, as in David's image, with the names of military leaders, including "BONAPARTE," "HANNIBAL," AND "KAROLUS MAGNUS," though Wiley has added "WILLIAMS," lending equal importance to the name of his model.

The long history of American portraiture had developed out of the European tradition where it communicated the subject's wealth, social standing, and cultural significance. By depicting an anonymous young black man in what Wiley has called a "hyper-heroic" depiction - using a monumental canvas and reducing the scale of the horse to emphasize the figure of the rider - the work reflects his belief that "art is about communicating power, and it's been that way for hundreds of years...What I choose to do is take people who happen to look like me, black and brown, people all over the world increasingly, and allowing them to occupy that field of power." At the same time, his work critiques the marginalization and disenfranchisement of black males in contemporary America. A pioneering example of Identity Politics, the work expresses the artist's statement, "My painting is about the world that we live in. Black men live in the world. My choice is to include them. This is my way of saying yes to us."

Oil on canvas - Brooklyn Museum of Art, Brooklyn, New York

American Art (Early-1900)

Native American Art

Before Europeans colonized North America, rich, complex art traditions flourished among many indigenous tribes who had developed a highly stylized vocabulary that employed complex geometric patterns and used near abstracted forms that both evoked the natural world and symbolized ancestral and mythological stories. The objects were often utilitarian and, at the same time, imbued with ritual significance. However, the newly arrived colonists in the Eastern United States primarily viewed those traditions as curiosities or arts and crafts, while aspiring to British fine art traditions and cultural values. Native American artists adapted the new materials and techniques brought by the colonists, including floral embroidery, beads, and silver smithing.

At the same time, some indigenous artists developed a European style to depict native subjects. David Cusick, a Tuscarora artist, published his Sketches of Ancient History of the Six Nations in 1828, and, along with his brother Dennis, a watercolorist, established the Iroquois Realist School. The first Native American art movement included over 25 Iroquois artists, who employed drawing, painting, and printmaking to realistically depict their tribe's beliefs, history, fashion, and lifestyle. Edmonia Lewis, of Mississauga Ojibwe and African-American descent, became internationally known for her Neoclassical sculpture, like The Death of Cleopatra (1876), exhibited at the Centennial Exposition in Philadelphia. In the early 1900s, Native American art began to receive national and international attention. The Kiowa Six, Spencer Asah, James Auchiah, Jack Hokeah, Stephen Mopope, Lois Smoky, and Monroe Tsatoke, were celebrated for their Ledger drawings that employed strong outlined, flat areas of bold color. The group exhibited at the 1928 First International Art Exposition in Prague and the Venice Biennale in 1932.

Folk Art

Much American Folk Art is utilitarian in nature, as sculptures were primarily figureheads for ships, weathervanes, and carved gravestones, but framed embroideries and velvet paintings were also made for wall decorations. Early American folk painters were called limners, from a term limning, meaning, "to outline in clear, sharp detail." Often self-taught, limners travelled from town to town and made a living by offering to paint anything, from signs for local merchants to farm implements and carriages. As the colonies reflected the British cultural values that viewed portraiture as a sign of social standing, fine art portraitists like the French born Henrietta Johnston, who emigrated to Charleston, South Carolina around 1705, gravitated to the cities, while limners made it possible for ordinary people in small towns to have their portraits painted. Boldly colored and outlined without modeling or shading, folk art portrayals were often intimate, depicting the sitter with a few objects that were of personal significance. Beginning his career as limner, Edward Hicks became famous for his The Peaceable Kingdom (1829-31), a work that expressed his Quaker values in a dynamic folk style. Folk art also drew upon African American traditions; in the 1880s Harriet Powers, a former slave, began exhibiting her quilts, depicting powerful narratives in bold color and geometric forms and patterns.

American Architecture

After the Revolutionary War, when the young nation was building its identity, early American architecture drew from British and Neoclassical architecture. Based on the work and theory of the Venetian Renaissance architect, Andrea Palladio, Neoclassicism was the dominant architectural style in 18th-century Europe. Thomas Jefferson, the third president of the United States, was also an innovative architect, and his design for Monticello (1772-1809), his home in Virginia, exemplified the Neoclassical style, employing a Palladian portico with four colored columns. During his Presidency, his ideas also informed Benjamin Henry Latrobe's designs of the U.S. Capitol building, launching what became known as the Federal style, favored for official buildings.

Developing around 1830 within the context of Neoclassicism, Beaux-Arts architecture rejected Neoclassicism's formality to incorporate elements from Renaissance, Baroque, and Late Gothic architecture. In the United States, the Beaux-Arts style, led by Richard Morris Hunt, became known as the "American Renaissance," or "American Classicism." Hunt actively promoted the popular style, which was employed in designs for private mansions and public buildings, including the Biltmore House (1889-95) built for the tycoon George Vanderbilt. In the 20th century, American Beaux-Arts architects returned to less ornamental and classical designs, exemplified by Henry Bacon and Daniel Chester French's Lincoln Monument (1914-22).

Beginning in 1890 and influenced by the British Arts and Crafts movement and Japonism, the highly influential Art Nouveau movement featured organic, flowing, floral motifs. Art Nouveau architects viewed the building, its interior spaces, and details, as a unified whole. Louis Comfort Tiffany, Louis Sullivan, and Frank Lloyd Wright were influenced by Art Nouveau. Sullivan's Wainwright Building (1891) used a frieze with a decorative motif of celery-leaf foliage, decorative spandrels, and an elaborate entrance door. Such architectural motifs became popular for skyscrapers and high rises, as seen in New York's Decker Building (1892). Later, in the 20th century, Art Deco was adapted to Public Works projects and iconic buildings such as William Van Alen's Chrysler Building (1930).

Beginning in 1914, the International Style emphasized the use of steel, glass, and concrete. Emerging during the aftermath of World War I and viewed as reflecting the modern age, it was often used for postwar housing. Austrian architects Richard Neutra and R.M. Schindler introduced the style when they moved to America in the 1910 and worked with Frank Lloyd Wright. Though both men created notable International Style buildings, as seen by Neutra's Lovell Health House (1929), the aesthetic did not truly flourish in the United States until after World War II, when economic expansion led to a boom in skyscraper construction. Leading architects, including Walter Gropius, Marcel Breuer, and Ludwig Mies van der Rohe, came to the United States in the post-war period and taught a new generation of American architects, while designing notable buildings. Mies for instance, built the Seagram Building (1954-58) in New York and the campus of the Illinois Institute of Technology in Chicago (completed in 1956). The International Style, with its glass curtains and industrial construction, was also used for fast-food restaurants and gas stations as America undertook construction of new interstates, connecting the country from coast to coast.

Beginning in 1950, Brutalism, also called New Brutalism, was a style of massive architecture that primarily employed unfinished, precast concrete. The style became popular for university campus buildings, performance art venues, libraries, government buildings, and corporate offices throughout the United States. Paul Rudolph was a leading proponent of the style as seen in his Yale Art and Architecture Building (1958). Due to American enthusiasm for the style, European architects adopted the style in their major commissions; Le Corbusier with Oscar Niemeyer, Wallace Harrison, and Max Abramovitz designed the United Nations Headquarters (1948-52), and Marcel Breuer worked with a number of American architectural teams to design Boston City Hall (1963-68). Breuer and Hamilton Smith's Breuer Building (1966), home to the Whitney Museum of American Art and later an expanded Metropolitan Museum, was also a trendsetting Brutalist design.

Hudson River School (1826-70)

The Hudson River School, led by Thomas Cole, who was born in Britain but emigrated to the United States when he was seventeen, was the first recognized American art movement. Centered in upper New York state, which was then wilderness, the artists associated with the movement emphasized the sublime and unique beauty of the American landscape. Influenced by Romanticism's concept of the sublime and Naturalism's emphasis on precise observed detail, Cole's landscapes like Kaaterskill Upper Fall, Catskill Mountains (1825) and Dunlap Lake with Dead Trees (Catskill) (1825) depicted American scenes to evoke the limitless possibilities of the new nation.

Following Cole's death in 1848, Asher B. Durand, influenced by the French Barbizon School, led the turn toward a more naturalistic painting. The artists Frederic Edwin Church, Albert Bierstadt, John Frederick Kensett, George Inness, and Thomas Moran formed the second generation. Their works became enormously popular, as the exhibition of just one panoramic painting could draw thousands of visitors. In the 1860s, as Manifest Destiny with its call to go West became a dominant national force, Bierstadt and Moran turned their attention to panoramas of the dramatic western landscape, and, along with William Keith and Thomas Hill, were sometimes called the Rocky Mountain School. Their works also inspired and informed the movement to preserve America's natural wonders, including the Yellowstone and Grand Tetons Parks. Alternatively, the intimate scale and feeling of George Inness's works like The Delaware Valley (c.1863), and John Frederick Kensett's depictions of light reflecting on bodies of water played a pioneering role in developing what later came to be called Luminism.

Luminism (1850-75)

The term Luminism was developed by art historians in the 1950s to identify a style that flourished from 1850-1870 among a number of American landscape painters. They drew upon a number of influences, including the landscape painting of the Dutch Golden Age, photography, and the genre landscapes of George Harvey, William Sidney Mount, and George Caleb Bingham. John Frederick Kensett, who led the movement, emphasized the landscape itself, with very little, if any, human presence; he focused on the play of light and atmosphere upon a body of water, as seen in his View of the Shrewsbury River, New Jersey (1859). Rather than exploring new vistas and rugged landscapes, each of the Luminists was associated with a particular locale, as the artist returned to the same scenes, painting the changing light and atmosphere from day to day or season to season. The Luminists, who included Kinsett, Fitz Henry Lane, Jasper Francis Cropsey, Sanford Robinson Gifford, and Martin Johnson Heade, preferred small-scale intimate works that emphasized the individual's communion with nature, reflecting Ralph Waldo Emerson and Henry David Thoreau's philosophy of Transcendentalism, which held that spiritual truth was revealed in the contemplation of nature.

Tonalism (1870-1915)

Tonalism emerged in the early 1870s in James McNeill Whistler's series of Nocturnes that emphasized tonal harmonies, often in muted greens, blues, and dark colors, to depict landscapes at twilight. Of works like his famous and controversial Nocturne in Black and Gold: The Falling Rocket (c.1875), Whistler said, "A nocturne is an arrangement of line, form and color first," but he also felt tonal harmonies were the visual equivalent of musical compositions. Born in America, Whistler lived most of his life in Britain where he played a pioneering role in a number of movements, including Japonism, the Aesthetic Movement, and the Anglo-Japanese aesthetic. Tonalists George Inness and Albert Pinkham Ryder were also influenced by the Barbizon School. Using gold and brown tones to depict a landscape at sunrise or sunset, Inness emphasized spiritual expression in works like Sunrise (1887), while Ryder often introduced a mythological narrative element into his mysterious landscapes that were precursors of Symbolism. In 1899 Henry Ward Ranger founded the Old Lyme Colony in Connecticut, seeing it as an "American Barbizon." A second generation of Tonalists, including Allen Butler Talcott, Henry Cook White, Bruce Crane, William Henry Howe, Louis Paul Dessar, and Jules Turcas, joined the artistic colony. In 1903 Childe Hassam joined the colony and briefly took up the style before abandoning it in favor of American Impressionism.

American Impressionism (1880-1920)

American Impressionism was primarily inspired and influenced by the French Impressionists, including Claude Monet, Pierre-August Renoir, and Alfred Sisley among others, who first exhibited together in Paris in 1874. French Impressionism influenced both the expatriates John Singer Sargent and James McNeill Whistler, though neither fully embraced the movement. Mary Cassatt became America's first well-known Impressionist. Moving to Paris in 1866, she became close friends with Edgar Degas and associated and exhibited with many of the leading Impressionists. Her works, full of vibrant color, expressive brushstrokes, often portrayed intimate gatherings in relaxed bourgeois environments, as well as many depictions of a mother and child, and were enormously popular in the United States. In 1883, the first U.S. exhibition of the French Impressionists Monet, Renoir, Pissarro, and Manet influenced the artists William Merritt Chase, Childe Hassam, and Edmund C. Trabell. A number of thriving artist colonies devoted to American Impressionism developed throughout the country.

American Art (1900-1950)

Ashcan School (1900-15)

The Ashcan School was a group of artists including John Sloan, George Luks, Everett Shinn, and William James Glackens, all students of Robert Henri, then located in Philadelphia. Drawing upon earlier masters, including Diego Velázquez, Francisco de Goya, and the later Realists like Édouard Manet, the group employed classical methods to create realistic and gritty scenes of modern, working-class life, or what Henri called "art for life's sake." After the group relocated to New York City, a second generation of artists followed, including George Bellows, whose Disappointments of the Ash Can (1915) gave the movement its name. In 1908, Edwin Lawson, Arthur B. Davies, and Maurice Prendergast joined the core group, known as The Eight, as they formed their own exhibition in opposition to the then dominant system of juried exhibitions by the National Academy of Design. Using gestural brushwork and a dark color palette, the artists' unidealized subjects aligned them with an innovative modern sensibility, which influenced the later Social Realism movement and the artists Edward Hopper and Ben Shahn. Sloan and Henri also taught and influenced many of the artists of the Fourteenth Street School.

Photography: Pictorialism, Straight Photography, and Beyond (1902-Present)

Modern Photography, emerging out of scientific explorations of botany, archaeology, and movement, incorporated a host of artistic styles. Pictorialism was an international photographic movement that used darkroom manipulations, composite images, posed and staged scenes, and blurred and soft focus to emphasize individual expression. Beginning in Britain in the 1840s, by the mid-1880s Pictorialism had become a flourishing movement. In 1902 in New York, Alfred Stieglitz and Edward Steichen advocated for the importance of photography and launched the journal Camera Work in 1903 and The Little Galleries of the Photo-Secession in 1905.

Straight Photography, emphasizing the technology of the camera itself, rejected Pictorialism in favor of sharply focused images that were rich in detail. In 1907, Stieglitz in his photographs like The Steerage began to explore the "straight" image without prior posing of the subject or subsequent use of darkroom manipulations. He influenced a number of leading photographers and ardently promoted the works of Paul Strand in a 1917 issue of Camera Work. Many of these works employed close-up shots with tight cropping to emphasize near abstract patterns and form, as seen in Strand's Porch Shadows (1916). Straight Photography became a dominant trend that continues to the present day.

The emphasis upon abstract pattern and form influenced the development of Abstract Photography, which began in 1916 with Alvin Langdon Coburn's Vortographs (1916). Stieglitz called him the "youngest star" of the Photo-Secession group, and Coburn began exploring abstract images as early as 1912. Both Paul Strand and Stieglitz were to explore near abstraction as well.

In 1931, Edward Weston, Imogen Cunningham, Ansel Adams, and Willard Van Dyke formed Group f/64 in San Francisco. The movement emphasized what Van Dyke described as "pure photography...defined as possessing no qualities of technic, composition or idea, derivative of any other art-form" and made its public debut in a 1932 exhibition at the M.H. de Young Museum. Though many of the photographers had begun their careers as Pictorialists, they now firmly rejected that movement's emphasis on fuzzy "artistic" effects, composed scenes, and darkroom manipulations. Their subject matter was often ordinary and frequently taken from nature, as Cunningham became known for her series of Magnolia blossoms, Weston for his images of a single green pepper, Adams for his images of Yosemite Park. Group f/64, and in particular Weston and Adams, also revitalized Abstract Photography, which re-emerged in the 1940s in the works of Minor White and Aaron Siskind.

Synchromism (1912-24)

Synchromism emphasized abstract paintings that primarily employed the color scale to create a visual "symphony," or musical effect. Morgan Russell and Stanton Macdonald-Wright, both young Americans living in Paris, founded America's first avant-garde movement in 1912. They adopted the color theories of Ernest Percyval-Tudor, a Canadian living in Paris, who believed that twelve colors of the spectrum corresponded to the twelve steps of the musical scale, and Russell coined the name for the movement by combining "symphony" with "chrome." Russell's Synchromy in Green (1913) launched the movement at the 1913 Salon des Indépendants in Paris, where it influenced Lee Simonson, a modernist theater set designer, and John Edward Thompson who later became known as the "dean of Colorado art" for introducing modern art to the area.

Harlem Renaissance (1920 - early 1940s)

The term Harlem Renaissance defines a period when music, literature, theater, painting and sculpture flourished within the rich and vibrant culture of New York's Harlem neighborhood. The movement, known for diverse styles, celebrated the "New Negro," a concept advanced by writer Alain Locke that emphasized a new African American sense of dignity, founded in equal rights and connected to the rich cultural traditions of Africa and Egypt. Following the Great Migration that began around 1910 when many African Americans left the southern states for the greater opportunity and freedom of the north, vibrant communities developed in Harlem as well as Chicago and Philadelphia. sculpture Ethiopia (1921) was an early pioneering influence, and international success of the earlier African American artists Mary Edmonia Lewis and Henry Ossawa Tanner became a defining model. Working in a variety of styles, artists including Aaron Douglas, Augusta Savage, Archibald J. Motley Jr. and the photographer James Van Der Zee became leading figures of the new movement. Their work and teaching subsequently informed a subsequent generation that included Jacob Lawrence, Beauford Delaney, and William H. Johnson.

Fourteenth Street School (1920-40)

In the 1950s, the term Fourteenth Street School was developed to define the works of Kenneth Hayes Miller, Isabel Bishop, and Reginald Marsh made in the 1920s and 1930s. Their subjects were taken from the New York neighborhood around Union Square and Fourteenth Street. The area, known as the "poor man's 5th Avenue," was a rising mercantile center, featuring retail department stores, whose sales, featuring the latest fashion at inexpensive prices, drew thousands of middle-class shoppers. Miller, a leader of the movement, began painting portrayals of the women shoppers in the 1920s. Teaching at the Art Center League, he influenced Bishop and March, as well as Raphael Soyer and Edward Laning, who also became later members of the group. Influenced by the Renaissance and Baroque masters, the group's figurative treatments often lent a kind of classical dignity to the portrayals of matronly shoppers, office girls, and career girls, who were seen as the embodiment of the "New Woman" and progressive prosperity. Due to realistic treatment of modern life, the movement is often included under Social Realism, though it shared little of that movement's attack upon the status quo or interest in political content.

American Regionalism (1928-43)

American Regionalism was not a deliberately formed movement but a style and approach that developed organically in the works of Thomas Hart Benton, John Steuart Curry, and Grant Wood. The three emphasized realistic depictions of rural life and ordinary situations, and each of them was associated with a particular region: Curry with Kansas, Benton with Missouri, and Wood with Iowa. They drew upon a number of divergent influences: Wood was influenced by the Northern Renaissance artist Hans Memling, Benton had been part of the Synchromist movement, and Curry utilized his prior experience in illustration, but their work consistently rejected modern European art and abstraction, in favor of a figurative approach to subjects that reflected what they saw as a uniquely American spirit. Wood's American Gothic (1930), when awarded a bronze medal at an Art Institute of Chicago competition, publicly launched the movement, as the work received national attention in newspapers and magazines. By the end of the 1930s, as Fascism threatened Europe, the movement's identification with a nationalist art came under critical fire, though other artists, including the well-known illustrator Norman Rockwell and the artist Andrew Wyeth continued to portray realistic scenes of ordinary American life, often connected to particular regions.

Social Realism (1929 - late 1950s)

Social Realism developed organically among artists who emphasized realistic depictions of the lower and working class, often within an urban environment, in order to radically transform society. Focusing on the plight of workers, the artists associated with the movement were influenced by the murals of José Clemente Orozco, the rise of labor rights organizations, and the call to worker's rights from leftist organizations like the John Reed Society. The movement initially drew upon the optimism following the Mexican and Russian revolutions and was further shaped by the global depression that began in 1929 as well as the rise of Fascism in the 1930s. Rejecting European avant-garde movements for their isolation from social issues, artists like William Gropper, Hugo Gellert, Max Weber, and Moses and Raphael Soyer viewed art as a weapon to fight the capitalist exploitation of the working class. The artists Ben Shahn, Philip Evergood, and Antonio Berni were also important members of the movement, as were Aaron Douglas and Jacob Lawrence, both also part of the Harlem Renaissance. In the 1930s, WPA-sponsored documentary photographers, including Dorothea Lange and Walker Evans, were loosely associated with the movement as they depicted the rural poor and the devastating impact of the Great Depression, as well as the Dust Bowl that ravaged the agricultural Midwest.

American Art (1950-Onward)

Abstract Expressionism, Color Field Painting, Post-Painterly and Hard-Edge Abstraction (1943-65)

Abstract Expressionism began in the early 1940s, centered in New York and led by Jackson Pollock, Clyfford Still, Willem de Kooning, Mark Rothko, and Adolph Gottlieb. As the leading Surrealists fled Europe during World War II for New York, the Abstract Expressionists were influenced by Surrealism's emphasis on automatism, an art that tapped into the unconscious. While the artists had begun their careers painting representational images, they moved toward increasing abstraction. Peggy Guggenheim's Art of This Century Gallery exhibited and supported the emerging movement, and she commissioned Pollock's monumental and innovative Mural (1943). The critic Clement Greenberg played a leading role in advocating for the movement, emphasizing purely visual and abstract effects of the paintings. American's first international art movement, Abstract Expressionism also effectively established New York as the center of the modern art world and led to a number of other developments, including Color Field Painting, Action Painting, Post-painterly abstraction, and hard-edge painting.

Color Field Painting, which began in the late 1940s, led by Clyfford Still, Mark Rothko and Barnett Newman, emphasized color as a powerfully expressive object. Still's canvases deployed bold colors in jagged forms; Rothko turned toward diaphanous rectangles of color, and Newman created "zip" paintings, where vertical strips of color intersected large horizontal fields of color. Greenberg championed Color Field Painting, with its emphasis on flatness and non-illusionistic space, as the way forward for advanced painting.

In 1952, influential art critic Harold Rosenberg in his essay "The American Action Painters" focused on the act of the artist in deciding to paint, thus coining the term Action Painting in favor of Abstract Expressionism. Franz Kline, Willem de Kooning, and Jackson Pollock were associated with the term, as Rosenberg saw their works as emphasizing the event and process of painting itself. The spontaneous movements of the artist, random drips and splashes, and energetic gestures, resulted in a work that conveyed the action of the work's making.

In 1964, Greenberg curated the exhibition Post-Painterly Abstraction for the Los Angeles County Museum of Art. The show included work by 31 artists, including Morris Louis and Helen Frankenthaler, as well as the West Coast artists Sam Francis and John Ferren. Ellsworth Kelly, Howard Mehring, Jules Olitski, and Kenneth Noland were also included. Greenberg wrote that these artists "have a tendency...to stress contrasts of pure hue rather than contrasts of light and dark...In their reaction against the 'handwriting' and the 'gestures' of Painterly Abstraction, these artists also favor a relatively anonymous execution." The Washington Color School, led by Noland and included Gene Davis, Morris Louis, and Thomas Downing among others, emphasized abstract art where color was emphasized to create form.

Drawing from the Color Field Painters, hard-edge painting was a term that defined a trend toward economical forms, impersonal execution, and clean lines. In the 1950s, Californian art critic Jules Langsner described the trend that used "forms [that] are finite, flat, rimmed by a hard, clean edge...They are autonomous shapes, sufficient unto themselves as shapes." In the 1960s the trend was also associated with Al Held, Ellsworth Kelly, Morris Louis, Frank Stella, Miriam Schapiro, and Kenneth Noland.

Around 1950 in the Bay Area of San Francisco, David Park, Richard Diebenkorn, and Elmer Bischoff rejected pure abstraction in favor of figurative subjects. The Bay Area Painters also included Manuel Neri, Nathan Oliveira, and Joan Brown. Many of the artists had begun their careers as Abstract Expressionists and retained elements of that movement in their landscapes and portraits, while at the same time celebrating local culture and landscape.

Also, by the mid-1950s a number of Second Generation of Abstract Expressionists, including Jack Beal, Jane Freilicher, and Nell Blaine, rejected the movement and turned toward figurative art. Including Fairfield Porter, Alex Katz, and Lois Dodd, the loose association of New York artists spearheaded a new emphasis on realism that became known as Contemporary Realism.

Neo-Dada (1952-70)

Beginning in 1952, Neo-Dada developed, as Jasper Johns, Allan Kaprow, and Robert Rauschenberg, began to employ "readymades," mass media, and performances. The artists rejected the existentialist heroics connected with Abstract Expressionism in favor of mundane subjects and blurred the traditional boundaries between media. Influenced by Marcel Duchamp and Dada, the movement had its start at Black Mountain College in North Carolina in 1952 and included Rauschenberg, the choreographer Merce Cunningham, and the composer John Cage. Cage's Theatre Piece No. 1 (1952) exemplified the group's emphasis on audience interaction, multiple media, and the role of chance.

Allan Kaprow created "environments," using sculptural collages to create installation pieces and later, after taking Cage's class, added aural components. He developed the term "happenings" to describe the quasi-theatrical events where, influenced by Futurism's concept of the event as overwhelming all boundaries and Dada's emphasis on the role of chance, the boundary between event and audience was broken.

Many Fluxus artists, including George Brecht, Robert Whitman, and Robert Watts, were interested in Neo-Dada and happenings. Fluxus, described as an "anti-art" movement, had utopian goals of wanting to change one's relation to art and to underscore the artfulness of everyday objects and actions. Leading members of the group Dick Higgins, Jackson Mac Low, and Al Hans met in Cage's 1959 class at the New School. Fluxus artists often used humor to undercut and dismiss high art. George Maciunas, the founder of Fluxus, described Fluxus as "a fusion of Spike Jones, gags, games, Vaudeville, Cage, and Duchamp." Fluxus was an international movement that also included Yoko Ono, Nam June Paik, and Joseph Beuys. Paik pioneered the development of Video Art, when he presented his video footage of the Pope's visit to New York as a serious artwork in 1965.

Pop Art and Photorealism (mid 1950s-1970s)

Pop Art was an international movement that had begun in Britain in 1952, led by the Independent Group, including Richard Hamilton, Eduardo Paolozzi, and the architects Alison and Peter Smithson, but the American version became the trendsetting and dominant form. Led by Andy Warhol, Roy Lichtenstein, Claes Oldenburg, and James Rosenquist, the artists used images taken from mass media and popular culture to challenge the distinction between "high" and "low" art and to critique and celebrate consumer culture. Warhol, Rosenquist, and Ed Ruscha were influenced by their early work as graphic designers and illustrators.

Photorealism, also called Hyperrealism, painted photographic images projected onto a large canvas, often with an airbrush, to resemble a finished photograph. Richard Estes, Chuck Close, Robert Bechtle, Ralph Goings, and Audrey Flack drew upon different influences, including Pop Art and Minimalism, and employed a variety of techniques, as they worked independently of one another. They often depicted objects from consumer culture, as in Ralph Goings' McDonalds Pickup (1970) or Richard Estes's Supreme Hardware Store (1970).

Minimalism and Post-Minimalism (1960 - Present)

In New York in the early 1960s, Minimalist artists such as Donald Judd, Carl Andre, Sol LeWitt, and Robert Morris created works from industrial materials while employing a cool and anonymous approach. Influenced by Russian Constructivism, Minimalists emphasized the materiality of the medium as perceived by the viewer and preferred industrial materials and fabrication. Rejecting Greenberg's formalist conception of painting, they emphasized an approach that, using a minimum of shape, color, and other elements, was also called "Systemic Painting," or "Reductive Art." Frank Stella, Tony Smith, Richard Serra, Ronald Bladen, and Dan Flavin were associated with the movement that quickly became dominant in America and internationally, while informing other developments, including Post-Minimalism and the Light and Space movement.

Post-Minimalism included a number of trends, including Process Art, Performance and Body Art, Site-Specific Art, and some aspects of Conceptual Art. Art critic Lucy Lippard curated Eccentric Abstraction in 1968, an exhibition that included work by Louise Bourgeois, Eva Hesse, and Bruce Nauman, whose pieces were made of soft or pliable materials. Some artists associated with Post-Minimalism extended the Minimalist interest in anonymous and abstract objects into other areas, while others reacted against Minimalism's cool anonymous approach in favor of emotional expression. Lynda Benglis, Eva Hesse, and Louise Bourgeois used resins and latex, while Nancy Graves used materials to simulate animal hides, and the resulting works created an organic expressive effect. Sol LeWitt, Richard Serra, and Vito Acconci were also included among the Post-Minimalists.

Based in California and influenced by Minimalism, Robert Irwin began creating large installations using light sources in 1969 and pioneered what became known as the Light and Space movement. Larry Bell, James Turrell, John McCracken and Helen Pashgian were all associated with the movement that used industrial materials, including neon and argon lights, cast acrylic, and polyester resins to create perceptual experiences. Drawing upon new scientific research and technologies, they created works that emphasized the interaction of light and space.

Earth Art and Environmental Art (1960s - Present)

Also called Land Art or Earthworks, Earth Art was an outgrowth of Minimalism, as the earth itself became both the material object and the site specific to art, and artists used the site's available natural materials, such as mud, earth, and stone, to design large-scale projects that were keyed to the site's significance. Often including some element of performance, Earth Art shared certain trends with Post-Minimalism, including Performance Art, process art, and Installation Art. The 1969 Earth Art exhibition at Cornell University, which including the works of Robert Smithson, Walter De Maria, Michael Heizer, Robert Morris, Dennis Oppenheim, and Hans Haacke, launched the movement. The artists, like Smithson, were often inspired by ancient sites, including Stonehenge or the Native American Serpent Mound, and saw their works as subject to changing conditions and entropy, the devolution of a system over time. Nancy Holt, Richard Long, Agnes Denes, and Andy Goldsworthy were also leading Earth Work artists.

The movement influenced the development of Environmental Art, also known as ecological art. Emphasizing a non-invasive approach, Environmental artists saw themselves as collaborating with the environment and exploring human interaction with natural environments. Betty Beaumont, Andy Goldsworthy, Agnes Denes, Meg Webster, Olafur Eliasson, herman de vries, Nils Udo, and Chris Jordan are the leading artists of the movement. They employed a variety of approaches; Beaumont transformed power plant waste into an underwater reef in her Ocean Landmark (1978-80), while Goldsworthy, over a period of four years, working, as he said, "in collaboration with nature," arranged pieces of limestone from fields where he worked as a gardener to create his Pinfold Cones (1981-85).

Postmodernism (1960s - Present)

In the 1960s, a heady atmosphere of experimentation reigned, leading to the development of Conceptual Art, Feminist Art, Body Art, and Performance Art. Though these art movements were international, American artists played a significant role in their development, and their subsequent expansion into a number of trends.

Influenced by Minimalism's reductive simplicity, Conceptual art emphasized that the concept of a work was more important than its form or even completion. Sol LeWitt's "Paragraphs on Conceptual Art" (1967) became the de facto manifesto of the movement; he wrote that the artwork "no matter what form it may finally have it must begin with an idea." Walter De Maria, Ed Ruscha, Marina Abramović, Dan Graham, and the German artist Joseph Beuys were just a few of the leading artists who became part of the movement. In the atmosphere of experimentation, new trends developed, including Institutional Critique, led by an international array of artists, including Hans Haacke, Michael Asher, Daniel Buren, and Marcel Broodthaers, and The Pictures Generation, including Sherrie Levine, Cindy Sherman, Robert Longo, Barbara Kruger, and Richard Prince. A number of Conceptual artists created installation pieces, as Installation Art became a primary trend, employed in a number of movements. Additionally conceptual practices informed Neo-Geo, or Neo-Geometric Conceptualism, a term that defined the works of Peter Halley, Ashley Bickerton, Jeff Koons, and Meyer Vaisman following their 1986 exhibition in New York. Using appropriative strategies, the group used geometric form to ironically distance itself from abstract painting, while also using previous works as readymades that could be appropriated.

Out of the Civil Rights movement, the emerging Gay Pride movement, and anti-war fervor, Feminist Art developed in the late 1960s. Women's art organizations like the Art Worker's Coalition and Women Artists in Revolution were formed to address gender inequity and other feminist issues within the art community. Judy Chicago and Miriam Schapiro founded the California Institute of the Art's Feminist Art Project and Womanhouse, a project where women artists could collaborate and create major installations. Mary Beth Edelson, Lynda Benglis, Martha Rosler, Carolee Schneemann, Suzanne Lacy, Leslie Labowitz, Bia Lowe, Barbara Kruger, and the Guerilla Girls were leading feminist artists, as the movement explored diverse approaches, and the artists involved became associated with several movements simultaneously. Judy Chicago became famous for her Dinner Party (1974-79), an iconic example of both Feminist Art and Installation Art, while Carolee Schneemann's performances were pioneering in the Feminist, Body Art, and Performance movements. Feminist Art actively supported and inspired the development of Queer Art, focused on queer identity and connected to the Gay Pride movement and the AIDS crisis, and ushered in an era of Identity Art and Identity Politics that focused on the experience of marginalized groups and the inequities they faced.

In the 1960s, Performance art emphasized live events where the artist, sometimes with collaborators or performers, erased all boundaries between the artist and the artwork. The international movement drew upon a number of early avant-garde trends, including Dada, Futurism, and Surrealism, but was more recently sourced in the 1950s works of John Cage, Fluxus artists, and Allan Kaprow's happenings. Staging what were sometimes called "actions," performance artists often confronted the audience. The movement was closely linked to the development of Body Art, as American artists, including Chris Burden, Carolee Schneemann, and Hannah Wilke, employed their own body as the medium.

Ask The Art Story AI

Ask The Art Story AI