Summary of Direct Carving

The Direct Carving of wood and stone to create primitive, intuitive, and indigenous sculptures, masks, and effigies has celebrated a long history, dating back to the ancient times in many cultures. Yet, the term in art history and modern art is used to refer to the sculptural approach pioneered by Constantin Brâncuși in 1906. Rejecting the established and rigid sculptural practice, he emphasized the artist's solitary engagement, carving the work in line with the inherent qualities of the raw materials, an approach that emphasized both the materiality of the object and the process.

Also known as taille directe, Direct Carving was widely adopted among both contemporary and subsequent generations of artists in various movements and approaches to artistic expression, such as Expressionism, Cubism, Dada, Surrealism, Neo-Expressionism, Biomorphism, and Primitivism.

Key Ideas & Accomplishments

- Direct Carving was seen as a more authentic creative process in juxtaposition to the classical and traditional means of planning for and composing a final work. Thus reflecting a truer engagement with the material, and often connected with spiritual values, arising out of an elemental connection with what Brancusi called "the inner form," as he said, "direct cutting is the true road to sculpture." What emerged was an intuitive dance between sculptor and medium.

- The art of non-Western cultures, seen as expressing this more "primitive" and more genuine approach, was taken as an inspiration. Many indigenous cultures informed the Direct Carving aesthetic through their ancient artifacts and the personal resonance associated with such primal forms.

- By taking cues from the past, Direct Carvers married antiquity and modernism in a unique way that had not been seen before. By adding a contemporary remix to an ancient lexicon, the sculptures that emerged became a fine example of the way artists oftentimes mine history to evolve art on both personal and societal levels.

The Important Artists and Works of Direct Carving

The Kiss

This sculpture depicts two figures kissing, carved to accentuate their closeness within the block of stone from which they emerge. Intimacy is prevalent in their curvaceously embracing arms with bodies and faces that press together. Only a slight variance in hairstyle and contour evokes gender.

The simplified forms emphasize oneness, made convincing by the unpolished singularity and authenticity of the material. As art critic Nicholas Fox Weber wrote, "This is the purest of geometric sculptures, yet the bodies are completely lithe, and the eyes, which are represented so sparely, meet with an infinity of emotion...This stylized sculpture, a cube of stone, is the essence of connection."

Saying, "direct cutting is the true road to sculpture," Brâncuși's emphasis on elemental form and texture in this work was undoubtedly meant to artistically counter the romantic naturalism of Auguste Rodin's famous sculpture, The Kiss (1882). Rather than a polished surface, this work's surface is rough, enhancing the natural qualities of the limestone. As a result, the sculpture takes on an archaic quality, evoking ancient cultures but confined to none of them, as it becomes startlingly modern.

Limestone - The Philadelphia Museum of Art, Philadelphia, Pennsylvania

Homme accroupi

This sandstone sculpture depicts a crouching man. His compressed and tightly coiled form evokes a sense of dynamic energy, as if at any moment he might burst outward from the stone. The geometry of the block contrasts with the more organic and curvilinear lines of his form. Carving only a few lines, the artist stayed true to the elemental, almost abstract cube, which allows for a 365-degree perspective depending on where the viewer stands.

The work was acclaimed as a pioneering example of early Cubism when shown at Kahnweiller's Gallery in Paris in 1907. Art historian Edith Balas called it the most influential work of the period. At the same time, in the huddled figure's powerful expression, it also draws upon Derain's early Symbolist work.

Derain was a pioneer of both Fauvism and Cubism, and in this work, the artist, primarily known as a painter, brought a new vision to sculpture. Drawing upon his enthusiasm for pre-Columbian and African sculpture and the volumetric forms of Paul Cézanne, the artist has left the working marks of his chisel in the stone, creating a sense of the work as if it had been recently excavated from the earth.

Sandstone - MUMOK, Vienna, Austria

Tänzerin mit Halskette (Dancer with Necklace)

Carved out of a cylindrical log of wood, this work depicts a nude dancer, her body torqued in a tight spiral, counter to the forward movement of her legs. Roughly carved, it is reminiscent of a tribal artifact. As art critic Christopher Knight noted, "The painted wooden dancer exudes an animistic spirit, as if temporal nature is infused with conscious life. She's a modern totem."

Kirchner cofounded Die Brücke in 1905, a group of Dresden Expressionists who wanted to create "the bridge" between the modern era and the ancient past - here considering the past traditions of German woodcuts and wood working and those of non-Western cultures. Kirchner frequented the Ethnographical Museum, and as Knight noted, "was especially smitten with sculpture from Cameroon and Palau, so he started to carve." As the artist said, "How different that sculpture appears when the artist himself has formed it with his hands out of the genuine material, each curvature and cavity formed by the sensitivity of the creator's hand, each blow or tender carving expressing the immediate feelings of the artist."

Though he was most known for the powerful forms in his drawings and paintings Kirchner saw this innovative work in his oeuvre as exemplifying the aims of Die Brücke, as he reproduced it in a woodcut for the group. The Nazis later destroyed much of Kirchner's work as examples of what they called "degenerate" art, and, as a result, few of his wood sculptures survived. This work disappeared and was only rediscovered in the 1980s.

Painted wood - Los Angeles County Museum of Art, Los Angeles, California

Sun God (verso: Primeval Gods)

This sculpture presents a nude male figure, his arms and legs extended, with rays of sunlight streaming from his head. Reflecting the aesthetics of Egypt and carved in deep relief, the work creates an impression of virility and power. The subject's palms are opened as if holding up the world.

The piece is carved from Hoptonwood stone, a limestone found in Derbyshire that, used in decorative carving for memorials, tombs, and buildings including the Houses of Parliament, was profoundly connected to British historical and cultural tradition. It was ironic to use a stone denoted so heavily for manmade memorials and institutions in a way that reflected a more ethereal memorial for a mythological God.

At the time, Epstein was collaborating with Eric Gill, with plans to make a series of carved monumental sculptures to reflect what they saw as the primitive power and sensuality of Egyptian sculpture. Though the plan fell through, Epstein nevertheless made a number of the sculptures, including Sun Goddess Crouching and Sun Worshipper in 1910. During the same period, he was working in Paris on the Tomb of Oscar Wilde (1909-12), also carved from Hoptonwood stone, and as art historian Emma Chambers wrote, "The Sun God figure appears to grow out of the stone and its hovering position was reused by Epstein for the 'flying demon angel' on the Tomb of Oscar Wilde."

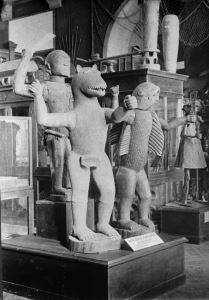

In the early 1930s Epstein returned to this sculpture, deepening the relief of the figure and adding Primeval Gods, a carved relief on the back of the stone. The relief depicted a massive figure, alluding to African sculpture, with two smaller figures carved on his torso. As a result, art historian Emma Chambers wrote, the work "is notable for the way in which it shows the development of Epstein's carved sculpture across two decades, his evolving relationship to non-Western sculpture, and the links between his work of the 1910s and the 1930, all in a single block."

Hoptonwood stone - Collection of the Tate, United Kingdom

Figure

This curvilinear form suggests the figure of a woman, emerging from and simultaneously one with the warm, rich beech wood. Her rounded contours are informed by the wood's natural contour lines. As art historian Sarah Victoria Turner wrote, "Moore thoroughly exploited the natural grain of wood in achieving the final form. Following the undulating grains of the wood also encourages our haptic sense of vision - in other words, looking evokes touching." Additionally, the figure evokes a landscape, elemental yet shaped by nature's forces.

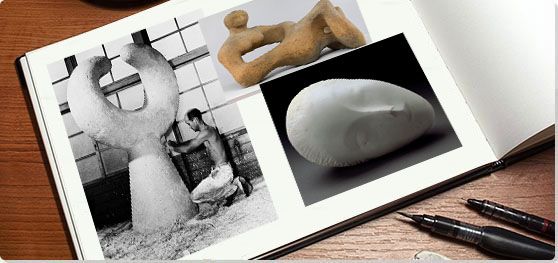

As Turner wrote, "Direct Carving was unquestionably central to Moore's practice and identity as a sculptor: between 1920 and 1940 nine in every ten of his sculptures, it has been claimed, were carved." Moore first began carving in stone in 1920 while studying at the Leeds Art School and continued his emphasis on the practice as he attended the Royal College of Art in London where he became aware of the divide between those who directly carved their works and those who were trained to copy sculpture, using pointing machines. While studying, Moore became fascinated with the carved sculpture of other traditions, of which he admired, as he wrote, "the intense vitality which it possesses, because it has been made by a people in close touch with life, who felt simply and strongly, and whose art was a means of expressing vitally important beliefs, hopes and fears." Accordingly, Moore's use of specific materials was, as Turner noted, central to the "development of his identity as a quintessentially 'English' sculptor connected to the local landscape."

Moore became the most celebrated English sculptor of the century and became influential internationally as his monumental sculptures can be found in noted art centers and cities throughout the world.

Beech - Collection of the Tate, United Kingdom

Mother and Child

This small, semi-abstract sculpture, carved out of Cumberland alabaster, evokes the figure of a reclining woman with her child balanced on her knees. The work was innovative both in its use of negative space, which as art historian Matthew Gale wrote, "carried a conceptual value, with the suggestion that the child had come from - and outgrown - the vacant space in the centre of the mother's body," and in being made of two pieces of stone to create what Gale and Chris Stephens called "a single integral sculptural mass."

Influenced by Brancusi's method of Direct Carving, Hepworth also shared his reverence for the materiality of the object. As she said, "I was fascinated by the kind of form that grew out of each sculpture, and by the kind of form that grew out of achieving a personal harmony with the material," Here, she has customarily used a local stone, one veined with warm colors, that, enhanced by the work's biomorphic form, evokes the undulating landscape of Cumberland. Subsequently she created works like Three Forms (1934), using three white stones carved in simple shapes to, as she said, show "the relationships in space, in size and texture and weight, as well as the tensions between forms."

Similar to Henry Moore, Hepworth's evolution toward abstraction stemmed from her Direct Carvings. The two artists are often confused and were friends and rivals, forging their careers with very similar aesthetics (intercut voids, concavities, and convexities) during the same period. Although Moore gained exhibition notoriety a few years prior to Hepworth, it has been argued that Hepworth was the first to pierce her stone. As their careers progressed, Moore's work conjured more toward the human figure as Hepworth remained connected primarily with landscape.

Cumberland alabaster on marble base - Collection of the Tate, United Kingdom

Dagger Child

This sculpture, carved of wood, which has been darkly painted, resembles a dagger, as if organically emerging from nature. Three defined and overlapping layers reaching upward to "petals" that are sharpened points. The vertical shape evokes both wounding and being wounded, as a tiny drop of red paint beads on the shortest blade, for in a sense, the object can be also be seen as three daggers, a kind of cryptic family unit with the shortest blade evoking the child. Remarkably simple, this elemental piece takes on a kind of archetypal and psychological weight, as if embodying the strangeness of dreams.

This work was part of Bourgeois' Personnages, a series of about 80 carved sculptures, as art historian Nancy Spector described, embodying "the essential themes and obsessions of all her subsequent work. Described by Bourgeois as her first truly mature artistic effort, these life-size, semi-abstract, vaguely anthropomorphic sculptures created between 1945 and 1955 functioned as surrogates for real people close to her - some departed, some forsaken, and some eminently present. " When exhibiting the pieces, the artist placed them in various groupings, as Spector noted, "to create a "reconstruction" of her past with this display of surrogates...the Personnages were as much conjured as they were carved, nailed, and painted."

Painted wood on stainless steel base - The Solomon R. Guggenheim Museum, New York, New York, New York

Modell fur eine Skulptur (Model for a Sculpture)

This sculpture, Baselitz's first, has a raw energy, reflecting a deliberately crude artistic technique, as the artist employed a chain saw and axe in order to create this wood block, as if severed from a tree, with the figure of a man, aggressively emerging but bound to it. Raising his arm in a furious gesture and painted roughly in raw and black, the colors of the Third Reich, the figure has been interpreted as by some scholars as a caustic commentary on Germany's past. Resisting art as social commentary, the artist attributed its inspiration to an edible souvenir available in Dresden markets, though he was also to state of the entirety of his work, "This idea of 'looking toward the future' is nonsense. I realized that simply going backwards is better. You stand in the rear of the train - looking at the tracks flying back below - or you stand at the stern of a boat and look back - looking back at what's gone."

Originally intending to send paintings to the 1980 Venice Biennale, Baselitz sent only this sculpture, which he had worked on in secret. At the Biennale, as The Musée d'Art Moderne de la Ville de Paris wrote for its 2012 Baselitz retrospective, "the sculpture, caused a furore...As both 'model' and 'idea of sculpture', however, it embodied the features of the works to come: categorical rejection of the elegant, aggressively crude handling, connections with a personal or collective history, axe-work and painted highlights."

The work, perhaps, reflects Baselitz's admiration for Kirchner's work, though as art critic Norman Rosenthal noted, it is also "based...on an African Lobi figure." Saying, "I don't like things that can be reproduced. Wood isn't important in itself but rather in the fact that objects made in it are unique, simple, unpretentious," Baselitz continued working in sculpture, as seen in his Die Dresdner Frauen (Women of Dresden) (1989), referencing the fire bombing of Dresden in 1945. At the same time, as Rosenthal noted, "During the 1980s, Baselitz's paintings became deliberately more crude, perhaps informed by his sculpture. Works such as Nachtessen in Dresden (Supper in Dresden, 1983) can almost be imagined as sculptures."

Limewood and tempera - The Ludwig Museum, Cologne, Germany

Sculpture Finding

Placed in a garden and carved of black basalt, this hexagonal stone takes on an elemental presence, enhanced by the asymmetrical contrast between smooth almost geometric planes and irregular areas of roughness. Man's relationship with medium is clearly delineated through the juxtaposing shades between the exterior beige and the interior brown areas representing the artist's hand. It is the perfect visual representation of Noguchi's own statement: "The presumption to work as I do comes from the ability of new tools to incise our will upon matter - like a meeting from the opposite ends of time to resume on another level the continuity that has gone on for eons."

After seeing a New York exhibition of Brancusi's work, Noguchi traveled to Paris in 1927 and began working as an assistant to Brancusi where he learned Brancusi's Direct Carving techniques. Subsequently he traveled to China and Japan where he practiced traditional arts including ink drawings and portraits sculpted in terra cotta. As Muchnic noted, "He has a special fascination for "abandoned stones" that "allow me to enter into their life's purpose.... It is my task to define and make visible the intent of their being." His sculpture was informed by a deep awareness of nature and environmental concerns, as evinced by this sculpture, carved in Japan from local basalt.

Granite - Yorkshire Sculpture Park, England

Beginnings

Predecessors

Leading up to the 1900s, sculpture was based on the traditional forms taught in the academies and employed by leading artists like Auguste Rodin. Sculptors used a somewhat collaborative process that relied upon help by skilled assistants. The sculptor would make the original work in clay, wax, or plaster, and assistants, using a pointing machine, would then carve the work in wood or stone. Plotting specific points on the raw material, the machine made it possible to create accurate copies and to enlarge or reduce the size of the original. But Direct Carvers soon emerged to reject this approach.

In the early 1900s, European museums and avant-garde artists began recognizing the works of other cultures as art, rather than merely crafts or utilitarian objects confined to historical or ethnographical interest. Artists began adopting elements of non-Western art's formal and stylistic qualities as innovative strategies and took up the techniques of Direct Carving. While, in actuality, most non-Western art was created within a complex tradition, where iconography, the materials used, and the process of creation followed specific rules and customs, the avant-garde artists, feeling they understood these exotic works intuitively, found specific inspiration in their raw and primitive powers of expression.

When Paul Gauguin first went to Tahiti in the early 1890s, he became enamored with its people and culture. He encountered the hand carved sculptures and objects of Tahitian art and, subsequently, made a number of Direct Carved works. As he later said, after viewing the non-Western works exhibited at the 1889 Universal Exposition, his view was that "sculpture like drawing...ought to be modeled 'harmoniously with the material.'" Gauguin's work had wide influence, informing Brâncuși's approach and inspiring Ernst Ludwig Kirchner's transition to sculpture. An exhibition of his work in 1910 in Dresden not only influenced other Expressionists but also fueled their further interest in African art.

The Arts and Crafts movement also promoted the search for a more primal authenticity. It began in Britain in 1860, rejecting industrialization while advocating for the creation of high quality handcrafted items in harmony with a more genuine lifestyle. Blurring the distinction between fine art and craft and between artist and craftsperson, the movement provided the theoretical underpinnings for Direct Carving.

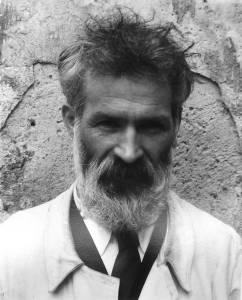

Constantin Brâncuși

Constantin Brâncuși's love of woodcarving developed during his rural Romanian childhood. At the age of 18, his hand-carved violin impressed a patron who helped him enroll in the Craiova School of Arts and Crafts. He went on to study at the Bucharest School of Fine Arts, before moving to Munich and then to Paris where he became part of the artistic milieu. He worked as an assistant in Auguste Rodin's workshop for two months, but left after feeling he had reached an artistic turning point. As he said, "I felt that I was not giving anything by following the conventional mode of sculpture."

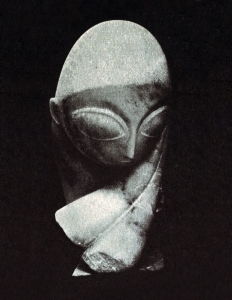

After deciding to pursue his own path, Brâncuși would pioneer Direct Carving. This new mode allowed him to engage with the material through every part of the process, letting texture, grain, and color inform the final work. He drew upon his deep knowledge and connection to Romanian folk art but was also influenced by Gauguin whose works he had seen at the 1906 Salon d'Automne and by the African sculptures he studied at the Trocadéro Museum in Paris. His simple forms often married geometry with biomorphism to capture, as he said, "not the outer form but the idea, the essence of things." His work was so influential, he is often called "the father of modern sculpture."

Adopted by European artists like Amedeo Modigliani, André Derain, Ossip Zadkine, Emile Nolde, Ernst Barlach, and Ernst Ludwig Kirchner, British artists including Jacob Epstein, Henry Moore, and Barbara Hepworth, the Surrealists such as Hans Arp, and even the Japanese American Isamu Noguchi, Direct Carving became part of the gestalt of modernism.

Concepts and Trends

Primitivism and Culture

The hand-carved objects of non-Western culture, including pieces from Mesoamerica, ancient Egypt, and Africa, influenced many early practitioners of Direct Carving. With their simple shapes and elemental lines, these non-Western works, whether carved in stone or wood, simplified and abstracted the figure, conveying a primitive connection to essential form. Avant-garde artists were often drawn to the art of specific cultures; Epstein's work was often influenced by Egyptian sculpture, whereas the elongated faces of Baule masks and figures inspired Modigliani. He would later cement this distinctive facial style in a series of sculptures that included his Woman's Head (1912).

The avant-garde's interest in non-Western art was often combined with a deep attachment to the artist's native culture. For example, art historian Sidney Geist traced the figure in Brâncuși's The First Step to a work from the Bambara people of Africa, while Edith Balas attributed its innovation to the influence of Romanian folk art. Brâncuși praised both traditions saying, "Only the Africans and the Romanians know how to carve wood." In Germany, when Ernst Barlach, who had been influenced by Asian art early in his career as an Art Nouveau artist, turned to sculpture in 1907, his wooden figures, such as his Magdeburge Ehrenmal (1929), drew upon German medieval religious sculpture. Both African art and German woodcut prints informed Ernst Ludwig Kirchner's work. This trend continued with subsequent sculptors like Henry Moore, who wrote, "Mexican sculpture, as soon as I found it, seemed to me true and right, perhaps because I at once hit on similarities in it with some eleventh-century carvings I had seen as a boy on Yorkshire churches." Isamu Noguchi learned Brâncuși's Direct Carving while studying with him but his work equally reflected Japanese aesthetic and cultural tradition.

Materiality and Inherent Nature

Direct Carvers often viewed the artistic process as being in an intimate collaboration with nature. With an utmost respect toward the material's unique properties, they would allow for the colors, textures, and inherent nature of the wood or stone to guide the finished work. As Brancusi wrote, "It is the hand that thinks and follows the thought of matter." Materials were carefully selected for their distinctive qualities, and sculptors often used indigenous materials with historical or cultural resonance.

Jacob Epstein's Sun God (1910) was made from Hoptonwood stone, a Derbyshire limestone historically used for official buildings, including the Houses of Parliament. In Epstein's sculpture, we therefore find the irony of the same stone being used to create both a modern artifact alluding to the mythological and ephemeral as is used in housing our manmade authoritative institutions. Meanwhile, both Hepworth and Moore used Cumberland alabaster, known for its veins and rich color that could be carved in accordance to resemble the natural forms of landscape.

Additionally, materiality itself could inspire. As Hepworth noted, "Carving to me is more interesting than modeling, because there is an unlimited variety of materials from which to draw inspiration." Explaining his preference for Mexican sculpture, Moore wrote of its "grim, sublime, austerity, a real stoniness," and further explained, "Its 'stoniness', by which I mean its truth to material, its tremendous power without loss of sensitiveness, its astonishing variety and fertility of form-invention."

Process

Direct Carving valued a raw and spontaneous approach to sculpture. Rather than working from models, sculptors felt they were involved in a more organic and intuitive relationship with the material, resulting in a liberated final form. As a result, the process often took on a spiritual or mystical quality, as it was viewed as creating a direct connection to nature from which emerged a synchronistic and elemental truth. As José de Creeft wrote, "As you probe deeper and deeper into the stone, accepting suggestions of its shape and structure and imposing on it your unfolding vision, you discover new beauty at every step." Sculptors emphasized a wood's grain or knots to suggest the features of a figure or to evoke biomorphic shapes. Using simple forms unadorned by detail, they sometimes polished the form to emphasize certain aspects of its character but, just as often, left it roughly finished, still bearing the marks of their tools, as the process itself became part of the final work. Many artists approached the process of Direct Carving without any pre-training in sculpture. This lack, as art historian Penelope Jane Curtis wrote, "actually cultivated the new stylization which was the result of the conjoining of different priorities with a resistant material."

Later Developments

The evolution of Direct Carving would go on to make its mark on the artwork of subsequent generations of artists and movements. Following World War II, artists like Louise Bourgeois, Isamu Noguchi, Georg Baselitz, Chaim Gross, and Marina Núñez del Prado, continued to employ similar approaches.

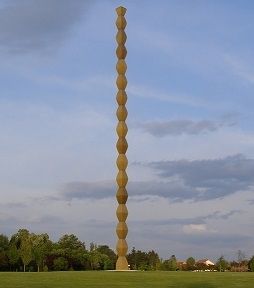

Direct Carving's emphasis on materiality can also be seen as a fundamental underpinning of Minimalism's focus on the material object as something whose form and function could be discovered in its simple, inherency alone. Brâncuși's work, particularly his Endless Column, first carved out of oak in 1918, and subsequently revisited, as William C. Agee noted, was a "sustained inspiration," for the Minimalists, who could find "Seeing in his single, unitary shapes with no extraneous parts a way to a new abstraction."

In 1984, the exhibition aptly titled "Ways of Wood" was held at four locations, highlighting the works of 48 artists, some of whom employed Direct Carving. The exhibit occurred the same year that Martin Puryear's Direct Carving was shown at the La Jolla Museum of Contemporary Art, and Ellsworth Kelly's wood sculptures, which he called "totems," were presented at a New York Gallery.

Along with Puryear, other leading artists have continued to inventively employ Direct Carving into the 21st century. Anish Kapoor's solo exhibition in Instanbul in 2013 centered around his stone sculptures created over three decades. In 2014-2015, Ursula von Rydingsvard's monumental cedar sculptures were shown in a solo retrospective at the Yorkshire Sculpture Park in the United Kingdom. In 2019, Peter Randall-Page's solo exhibition was held at Kloster Schoenthal sculpture park in Basel, Switzerland. Today, other artists working in Direct Carving include Milena Naef, Hanna Eshel, Matthew Simmonds, Christopher Kurtz, and Julian Watts, as well as the collaborative team of Daniel Dewar and Grégory Gicquel, and MANGLE, the Colombian team of María Paula Alvarez and Diego Fernando Alvarez.

Direct Carving's emphasis on process also informs Process Art's forms, spontaneously and unpredictably shaped by human actions and organic processes.

Ask The Art Story AI

Ask The Art Story AI