Summary of En Plein Air

En plein air, a French phrase meaning "in the open air," describes the process of painting a landscape outdoors, though the phrase has also been applied to the resulting works. The term defines both a simple technical approach and a whole artistic credo: of truth to sensory reality, a refusal to mythologize or fictionalize landscape, and a commitment to the idea of the artist as creative laborer rather than exulted master. Painting in the open air is recorded as far back as the Renaissance, but it was generally done in preparation for studio painting; only in the nineteenth century, through the cumulative efforts of artists such as John Constable, Camille Corot, and Claude Monet, did painting en plein air come to stand for the ethos of modernity and fidelity to nature which it still implies. More than any other movement, it was Impressionism that became synonymous with open air painting, which is thus also associated with the attention to light and atmosphere that defined that school. Today, en plein air painting, once considered an odd affectation, is what much of the public pictures when they imagine an artist at work, and is favored by many semi-professional and amateur artists.

Key Ideas & Accomplishments

- Painting en plein air allowed artists to capture the emotional and sensory dimensions of a particular landscape at a particular moment in time. It thus expressed a new spirit of spontaneity and truth to personal impulse within art. The ongoing popularity of nineteenth-century plein air painting today - as compared to academic historical paintings from the same period, for example - shows how the technique allowed artists to communicate directly to viewers, without intellectual artifice.

- Painting en plein air became particularly associated with the Impressionist movement, although it had been pioneered by earlier generations of artists, from English Romantic painters such as John Constable to the Barbizon School of central France. For that reason, en plein air painting often signifies a commitment to the loose, light, quick brushwork that marks out the Impressionist approach.

- Considered as an ethos rather than a technique, plein air painting casts a huge shadow over modern art as a whole, because it signified the honest, unadorned depiction of reality, and was thus often bound up with radical formal or social commitments. In the work of Courbet and Cézanne, for example, painting en plein air stood for cultural and stylistic revolution respectively, though was the latter link that became more influential, given Cézanne's huge influence on Cubism.

- The rise of painting en plein air across the nineteenth century was coextensive with the rise of landscape painting as a legitimate artistic genre. In the early nineteenth century, landscapes were only a worthy subject of attention if they provided the backdrop to a mythological or historical tableau. By the end of that century, it was a truism that landscapes. particularly natural landscapes, were worthy of attention in their own right.

Overview of En Plein Air

John Singer Sargent's oil painting An Out-of-Doors Study (1889) features the artist Paul Helleu relaxing with his wife, Alice. It shows how painting en plein air allowed painters to bring a new degree of intimacy and informality to their work, capturing their daily lives or those of their friends.

The Important Artists and Works of En Plein Air

The Hay Wain, Study

This landscape painting, depicting the lush countryside of south-east England, is focalized around the image of a hay wain - a horse-drawn cart for transporting hay - crossing a forded stream. A range of figures, including one on horseback accompanied by a black-and-white dog, populate the scene, but the emphasis is on the landscape as a whole, with human activity presented as integrated elements of the overall scene. Constable's approach to en plein air painting involved creating full-scale oil sketches such as this one, which has been compared favorably to the finished painting, The Hay Wain, which is based upon it . As the art historian C. K. Kauffmann puts it: "the finished picture in the National Gallery differs hardly at all in composition...It is by far the better known of the two, yet in some ways it is the sketch, with its rapid brush strokes, its flecks of white and green skimming the surface, and its generally broader treatment that accords more with modern taste."

Painting en plein air allowed Constable to cultivate a rapt attention to the natural world. This approach was influenced by Claude Lorrain's scientifically detailed studies of landscapes. Like Lorrain, Constable would often spend days on sketching trips in the countryside. His father owned the cottage depicted in this sketch, located on the River Stour dividing the counties of Sussex and Essex. Indeed, Constable had grown up within sight of the setting. Such familiar scenes, he remarked, "made me a painter, and I am grateful,...the sound of water escaping from mill dams etc., willows, old rotten planks, slimy posts, and brickwork, I love such things."

For Kauffmann, Constable's approach combines "two tendencies: he portrayed his native Suffolk and one or two other areas in a manner both more naturalistic than that of any of his predecessors and yet imbued with a deeply Romantic spirit." Shown at the 1824 Paris Salon, Constable's landscapes had a profound impact on French artists, including Corot and Rousseau and other leading artists of the subsequent Barbizon School.

Oil on canvas - Victoria and Albert Museum, London

Forest of Fontainebleau, Cluster of Tall Trees Overlooking the Plain of Clair-Bois at the Edge of Bas-Bréau

This landscape depicts the majestic oak trees of Fontainebleau Forest, their dense foliage and gnarled branches blocking out the horizon to the left, while the fringes of the Plain of Clair-Bois appear to the right, where cattle drink from a still pool. The central oak tree, its trunk illuminated by light, the deep shadows of the surrounding forest, and the turbulent sky of the open plain, romantically evokes the primal power of nature. As the art critic Christopher Knight wrote of Rousseau, "the forest primeval was his great subject. The chestnuts and ancient oaks of Fontainebleau replaced the elders of church and state as cultural symbols of enduring power, mystery and beauty."

Rousseau's en plein air work was innovative both for his vigorous and distinctive brushwork and because of his lifelong engagement with the Fontainebleau Forest, an engagement that also involved actively campaigning for the ecological preservation of the area. The influence of seventeenth-century Dutch landscape painters, such as Jacob van Ruisdael, can be seen in Rousseau's use of a low horizon and the vertical division of the plain into thirds on the right side of the canvas. Yet in his depiction of the forest to the left, Rousseau disrupts the "law of thirds" in order to emphasize the dynamic energy of the forest, as if it were overwhelming the formal logic of the pictorial space.

Rousseau's vigorous and expressive brushwork, as Knight noted, "identified [his] presence in the particular time and place recorded in the chosen landscape. Paint carried his distinctive, recognizable artistic fingerprint." A leading figure of the Barbizon School, Rousseau's influence on subsequent artists was so significant that in the twentieth century he became known as the leading precursor of the Impressionist movement.

Oil on canvas - Getty Center, Los Angeles

On the Oise

This landscape depicts the Oise River in France, its meandering course creating a diagonal from left to right, where it widens into a still reflective expanse. A flock of ducks grazes the green bank in the foreground, while a small boat is visible as it skims the other bank, whose edges are dense with thick trees. The low horizon-line creates a sense of serene expanse while simultaneously dedicating the top two-thirds of the canvas to the sky, its blue broken by mottled clouds, reflecting the sunlight that shimmers in the scene below.

Originally associated with the Barbizon School, Daubigny charted an independent path. He was particularly interested in depicting the play of light upon water, using loose brushwork, a luminous palette, and pure colors. As the art critic Sam Kitchener notes, Daubigny increasingly practiced painting en plein air, "scraping a palette knife across the canvas to create texture...and making quick dabs of colour; capturing nature 'as it was' meant attempting to capture it as it was experienced." Daubigny's innovations also included the use of a double-square canvas, a custom format that allowed him to create panoramic views. He was also one of the first artists to present his oil sketches and unfinished paintings as artworks in their own right, an approach adopted by subsequent artists such as Monet, Pissarro, and Vincent van Gogh. In 1857, Daubigny bought a boat and converted it into a studio in order to paint the views along the Oise River, influencing Monet's similar use of a boat from 1873 onwards.

Thought perhaps less well-known than the Impressionist artists whom he influenced, Daubigny was important as one of the first painters to use plein air technique to capture the impression of light on water. In this he was not only an inspiration to Monet and his generation, but also preempted the activities of the North American Luminist painters, who were similarly concerned with capturing the atmosphere of lake and riverside scenes.

Oil on wood - Indianapolis Museum of Art, Indiana

Orchard in Bloom, Louveciennes

A man and a woman tend the field in Pissarro's sunny springtime scene, the furrows plowed for a new season. A meandering path runs vertically just right of center, drawing attention to the horizon and to the clustered trees in the distance, while also emphasizing the bright new growth along its edges. Meanwhile, the shadows cast by the two trees form a horizontal line which frames the two workers. The painting conveys the bright promise of spring as a source of renewal, and conveys a sense of harmony between the human and natural worlds.

In composition, Orchard in Bloom expresses Pissarro's view that the artist should "work at the same time upon sky, water, branches, ground, keeping everything going on an equal basis and unceasingly rework until you have got it. Paint generously and unhesitatingly, for it is best not to lose the first impression." He had learned en plein air painting from Corot, though he eschewed the older artist's classical references, instead emphasizing a realist approach to contemporary landscapes. Moreover, while Corot finished his works in the studio, Pissarro painted his works, as art critic Karen Rosenberg wrote, "outdoors, often at one sitting, which gave his work a more realistic feel. As a result, his art was sometimes criticised as being 'vulgar,' because he painted what he saw: 'rutted and edged hodgepodge of bushes, mounds of earth, and trees in various stages of development.' According to one source, such details were equivalent to today's art showing garbage cans or beer bottles on the side of a street."

This painting was one of five works that Pissarro exhibited in the first Impressionist show in 1874. He went on to exhibit in all eight of the Impressionist exhibits, and his work profoundly influenced Paul Gauguin and Cézanne, who began painting en plein air with him and acknowledged him as "the master."

Oil on canvas - The National Gallery of Art, Washington DC

Carnation, Lily, Lily, Rose

John Singer Sargent's painting is named after the flowers that surround the two girls, though the title also references a popular song of the day. Dressed in long white dresses that glow with the lavender light of early dusk, the girls carefully attend to the glowing Japanese lanterns that they are preparing to hang in the garden. By cropping the landscape and using a close-up view Sargent makes the garden almost a decorative space, replete with intricate floral patterns. As the art historian and curator Richard Ormond writes, the painting presents "a kind of Garden of Eden, an invented garden dense with flowers and foliage. It combines the en plein air technique with Pre-Raphaelite and Aesthetic impulses." In departing from the direct expression of sensory reality, Sargent took en plein air painting in decadent new directions.

Influenced by Monet, Sargent adapted plein air technique, which was generally used for landscapes, to the creation of portraiture: the genre for which he became famous. As critic Sarah Churchwell notes, this particular painting "took [Sargent] two years to achieve, for he could only paint for 25 minutes each night in late summer: every evening at 6:45 Sargent 'would drop his tennis racquet', remembered a friend, and 'lug out the big canvas' from his 70ft-long studio into the garden, where he would paint for as long as 'the effect lasted'." This exhaustive process was made more grueling by an exacting eye for revision and correction. Sargent often scraped away what he had painted, in effect beginning again each evening, and eventually cut two feet off the canvas as he felt the resulting square would lead to a tighter composition.

This work played a significant role in restoring Sargent's reputation, which had been damaged by the scandal that greeted the display in Paris of his Madame X (1884), a portrait of a young socialite that was felt to be overly sexualized. After returning to England, Sargent began spending his summers in an artist's colony, which is where this work was created, featuring the daughters of a fellow artist. In 1886, the painting was purchased by the Royal Academy; today it remains one of Britain's most popular paintings.

Oil on canvas - Collection of the Tate, United Kingdom

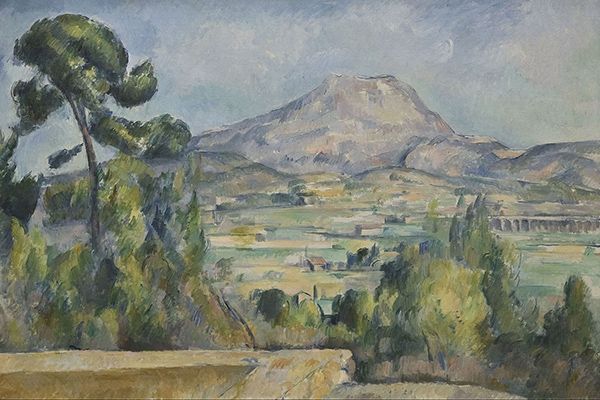

Montagne Sainte-Victoire

This work depicts Mont Sainte-Victoire, a landmark in southern France synonymous with Cézanne's work due to his many depictions of it and the surrounding landscape. In the distance, the railway bridge crossing the Arc River - also frequently painted by Cézanne - can be glimpsed. After traveling on the railroad in 1878, just six months after it had opened, Cézanne described the mountain as a "beautiful motif;" not long after, he began painting it.

From 1870 onwards, having been based in Paris, Cézanne spent more and more time in Provence, where he could develop his individualistic approach to art. His en plein air painting was particularly distinctive as he found the practice to be conducive to formal analysis of his subject, particularly the intersection of picture planes. His Post-Impressionist approach involved using color to create a sense of depth, and he viewed subjects such as the mountain in terms of elemental forms. He once decreed that the artist should "treat nature by means of the cylinder, the sphere, the cone, with everything put in perspective so that each side of an object or a plane is directed toward a central point."

It is difficult to overstate the significance of Cézanne's plein air painting to the development of modern art. In exploring and exaggerating the way in which objects could appear simultaneously from several perspectives on a single canvas, his work had a profound influence on the Cubist movement, particularly on its two figureheads Pablo Picasso and Georges Braque. Picasso and Braque's work, in turn, stands at the forefront of all the subsequent experiments in geometrical abstraction that define early-twentieth-century art.

Oil on canvas - Musée d'Orsay, Paris

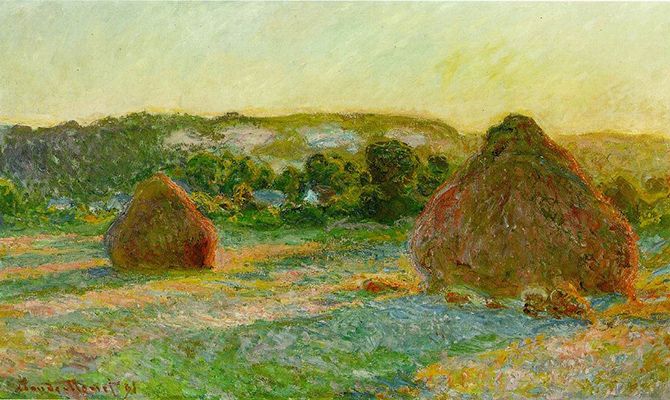

Stacks of Wheat (End of Summer)

Monet's famous Impressionist landscape painting series, generally known as "the Haystacks", focuses on the motif of two haystacks at different times of day and year. In this high-summer scene they appear luminous with light and rich color. Sunlight and shadow breaks the field into diagonals of variegated yellows and reds and bands of deep blue and greens, as the horizon on the right takes on an atmospheric glow.

This work is one of a sequence of twenty-five paintings depicting stacks of wheat in a farm near Monet's home at Giverny. Pioneering the serial motif, which became a signature of his work, Monet created his "haystacks" from the summer of 1890 until spring of the following year, seeking to capture the daily and seasonal variations of light and atmosphere. He sometimes used as many as a dozen canvases per day, painting quickly but also switching to a new canvas if the conditions changed.

Monet influenced not only his contemporaries but also subsequent artists, including Andre Derain, Vlaminick, the Fauvists, and Kandinsky, who said of the haystack series: "what suddenly became clear to me was the unsuspected power of the palette, which I had not understood before and which surpassed my wildest dreams."

Oil on canvas - The Art Institute of Chicago, Illinois

Beginnings

Sketching Outdoors in Italy

Although the first recorded use of the term "en plein air" was in 1891, painting outdoors evolved from the historical practice of sketching in the open air, which dated back to the Renaissance. As the art historian Paula Rea Radisich notes, "...artists have sketched outdoors from time immemorial," though the sketches were generally viewed as studies or preparatory work, for paintings created later in workshops or studios, rather than as autonomous works. An early example is Leonardo da Vinci's Landscape Drawing for Santa Maria Della Nave (1473), a drawing in ink and pencil depicting the Arno River valley in vivid detail.

During the mid-1600s, the Baroque-era painter Claude Lorrain pioneered an emphasis on landscape in its own right, informed by close observation of nature while sketching outdoors. As a result, Lorrain has been called "the father of outdoor painting." According to his contemporary Joachim van Sandrart, Lorrain "tried by every means to penetrate nature, lying in the fields before the break of day and until night in order to learn to represent very exactly the red morning sky, sunrise and sunset and the evening hours." He often revisited the same landscape in order to capture the light of changing hours and seasons, and his work was widely influential, as art historian Katherine Baetjer puts it, "because of the way in which the artist communicates the evanescent qualities of light."

Diego Velázquez in Spain

Diego Velázquez created what are thought to be the known first oil sketches in 1630, with his Villa Medici in Rome, Two Men at the Entrance of a Cave (c. 1630) and his View of the Gardens of the Villa Medici, Rome, with a Statue of Ariadne (c. 1630). These small works were also innovative in depicting landscape realistically, without including a classical motif. As the art critic Javier Portús writes, "in the 17th century...the representation of nature on canvas was very rarely enough by itself, so there was generally an accompanying mythological or religious 'story' to justify the work... Yet here, Velázquez transmits a more direct view of nature, and this is reinforced by the second of the two factors that make these paintings so singular...it was extremely rare for a painter to set up his canvas and painting tools in front of the subject of his work and paint it on the spot, as Velázquez did."

Pierre-Henri de Valenciennes in France

By the early 1800s, the practice and theory of Pierre Henri de Valenciennes had established oil sketching throughout Europe as an essential component of landscape painting. Living in Rome for several years, where he was influenced by Claude Lorrain, Valenciennes often worked outdoors. As he put it, "oil sketches must be done quickly, in no more than two hours. The artist must be minutely attentive to light and atmospheric conditions and be ready to lay aside one sketch and take up another as conditions changes." As the art historian Paula Rea Radisich has noted, oil sketching reflected "new trends in aesthetics. The sketch, it was thought, directly expressed the artist's individuality and subjective response to the motif, with a minimum of artifice and convention." At the same time, the practice reflected the era's emphasis on scientific observation, as Valenciennes advocated for viewing a particular place almost anthropologically in order to capture its specificity.

Valenciennes's treatise, Elements of practical perspective for the use of artists, connected from reflections and advice to a student concerning painting and particularly of the genre of landscape (1800), became a foundational text for landscape artists. As the art historian Philip Conisbee notes, his en plein air working method "became a cornerstone of landscape painting in the nineteenth century, from Camille Corot ...who studied with his precocious contemporary Michallon, to Paul Cézanne...who was mentored in plein-air painting by Pissarro."

John Constable in Great Britain

John Constable pioneered the use of full-scale oil sketches in his en plein air painting, as seen in his East Bergholt House, (c.1809). By painting on large canvases, he was at the forefront of the evolution towards viewing such sketches as works of art in their own right, their loose and vigorous brushwork seen as compellingly expressive rather than 'unfinished.' Deeply influenced by Lorrain's work, which he encountered in the late 1700s, Constable emphasized direct and often scientific observation, taking detailed notes of atmospheric conditions. As he wrote. "no two days are alike, nor even two hours; neither were there ever two leaves of a tree alike since the creation of all the world; and the genuine productions of art, like those of nature, are all distinct from each other." He also rejected the idea of art as imitation, stating that "when I sit down to make a sketch from nature, the first thing I try to do is to forget that I have ever seen a picture." Shown at the 1824 Paris Salon, Constable's landscapes profoundly informed the development of the Barbizon School.

The Barbizon School

The Barbizon School was a group of loosely associated artists, including Théodore Rousseau and Jean-François Millet, who lived and worked in the small village of Barbizon near the Forest of Fontainebleau from around 1830 onwards. As the art critic Grace Glueck writes, the group's aim "was to observe nature firsthand and paint it not in grand classical style but as seen and experienced in human ways." Influenced by Constable and Valenciennes, they advocated for detailed observation and a realistic approach to representation, seeking, as Rousseau wrote, to depict "faithfully...the simple and true character of the place."

French Realism

The Barbizon school's emphasis on naturalistic observation and en plein air technique influenced the leading artists of the day. Gustave Courbet, the pioneer of Realism, made the practice central to his depiction of rural landscape, and it came to exemplify his view of the artist as akin to rough-hewn laborers and craftsmen. The technique of en plein air painting was influenced in turn by Courbet's approach, particularly his frequent use of a palette knife to create a vigorous and heavily layered effect, emphasizing the material form of the work itself. Due to his friendship with Eugène Louis Boudin, a leading painter of marine landscapes, Courbet spent the mid-1860s painting en plein air along the Normandy coast, joined by James James Abbott McNeill Whistler and Claude Monet, as well as Boudin himself.

These kinds of acquaintances, formed and cemented by many days spent painting side by side outdoors, influenced a number of artistic innovations. Whistler pioneered Tonalism, a movement that emphasized atmospheric tonal treatments, often using a restricted palette of muted greens and blues to depict landscapes. As artists flocked to the villages of Normandy to connect with Eugène Louis Boudin, the Normandy School developed and influenced the formation of the Newlyn School in Britain, which similarly emphasized outdoor painting. However, Boudin's greatest impact was undoubtedly his influence upon Claude Monet, the pioneer of Impressionism.

Simultaneously, Jules Bastien-Lepage pioneered the movement of Naturalism after moving to the village of Damvillers, where he began painting en plein air works scenes of peasant life. Called the "grandson of Millet and Courbet" by Émile Zola, Bastien-LePage said he was "determined to keep simply to the true aspect of a bit of nature." Exhibited at the 1879 Paris Salon, his works, including The Haymakers (1877), made him internationally famous and influenced artists as varied as Marie Bashkirtseff, the Russian artists of the Peredvizhniki, and the Post-Impressionist Vincent van Gogh, all of whom adopted en plein air painting.

Hudson River School and Luminism

Lasting until 1880, the Barbizon School's emphasis on landscape and en plein air painting influenced the development of the first uniquely American art movement. The pioneer of the Hudson River School, Thomas Cole, depicted sublime, awe-inspiring landscapes showing the rugged expanses of his adopted homeland (he was born in Lancashire in England). Creating oil studies on extended trips into the wilderness, Cole innovated the use of thin paint and a copal medium to speed up drying times and enhance the flow of pigments, a technique employed by subsequent artists. Albert Bierstadt and the second generation of the Hudson River School adopted a more naturalistic approach while turning their attention to the landscape of the American West. Some second-generation Hudson River School artists, such as John Frederick Kensett and Fitz Henry Lane, employed en plein air painting to create realistic and precise depictions of atmospheric effects that were later described as Luminism.

Impressionism

![Claude Monet's <i>Coquelicots</i> [<i>Poppy Field</i>] (1873) depicts his wife and son in a field of poppies.](/images20/photo/photo_en_plein_air_10.jpg)

En plein air painting reached its artistic culmination with the Impressionists, so much so that the technique is often identified exclusively with the movement. As the art historian Margaret Samu notes, "this seemingly casual style became widely accepted...as the new language with which to depict modern life." Meeting in the early 1860s at the studio of the painter Charles Gleyre, Pierre-Auguste Renoir, Claude Monet, Alfred Sisley, and Frédéric Bazille realized they shared an interest in landscapes and scenes of contemporary life. Taking frequent trips to the countryside they painted outdoors, using, as Samu puts it, "short, broken brushstrokes that barely convey forms, pure unblended colors, and an emphasis on the effects of light...The artists' loose brushwork gives an effect of spontaneity and effortlessness." The Impressionists expanded the subject matter of en plein air painting, often depicting the leisure hours of the middle class. They also pioneered a serial approach that became an important trend in modern art. Monet was the first to make this approach his own, creating sequences of paintings from the early 1880s by revisiting the same locations at different times of day or different seasons: from hay stacks in a field to Rouen Cathedral or the water lilies in his pond, responding to the different atmospheric and light conditions he found upon each visit. Noted women en plein air painters, such as Mary Cassatt, Berthe Morisot, and Eva Gonzalès, emerged in the Impressionist era.

Concepts and Styles

The Rise of Landscape Painting

The rise of en plein air technique reflected the elevation of landscape painting to a high art across the nineteenth century. As art historian Laura Auricchio writes, "between 1800 and 1900, French landscape painting underwent a remarkable transformation from a minor genre rooted in classical traditions to a primary vehicle for artistic experimentation." In the early 1800s, Pierre Henri de Valenciennes established the French Academy's new Prix de Rome for "historical landscape." But many en plein air landscape artists, from John Constable to the Impressionists, eschewed historical and mythological references, preferring instead to depict elements of rural life, with the human figure often dwarfed by the landscape, but expressing a life lived in harmony with nature. Thus, as Auriccho notes, "if the century opened with Neoclassical landscapes, telling ancient tales set in distant lands, it closed with local scenes painted in the most experimental styles of the day."

The Influence of Technology

En plein air painting was enabled by various technological advances. Until the 1800s, artists had to grind their own pigments and mix them with various binding oils to be used for the work at hand, thus confining painting to the studio. In 1841 the invention of the paint tube by the artist John Goffe Rand transformed artistic practice. Tube paints could be easily transported, then spontaneously thinned, mixed, or used directly from the tube. By the 1850s the field easel or French box easel had also been invented, further simplifying the practice of painting outdoors. These easels - with an attached paint box, palette, and telescopic legs - could be quickly folded up and carried into the countryside. The rise of Impressionism in the 1860s was also informed, as art historian Margaret Samu notes, "by the development of synthetic pigments...providing vibrant shades of blue, green, and yellow that painters had never used before." The combined influence of these inventions was enormous; as Pierre-Auguste Renoir noted, "without tubes of paint, there would have been no Impressionism."

Engagement with Reality

Rejecting the Academy practice of imitating classical themes and the works of the Old Masters, plein air painters emphasized the artist's direct engagement with nature. Adapting to the conditions of the moment, the artist sought a direct sensory and emotional connection to the scene they were representing, informed by observation of specific details. Working in nature was a rigorous process, altering the dimensions of artistic creation as an experiential process. As Vincent van Gogh wrote, "just go and sit outdoors, painting on the spot itself! Then all sorts of things like the following happen - I must have picked up a good hundred flies and more off the four canvases that you'll be getting, not to mention dust and sand . . .When one carries them across the heath and through hedgerows for a few hours, the odd branch or two scrapes across them." Rapid and vigorous brushstrokes, slashes of the palette knife, the impasto effect of paint applied directly from the tube, gave a sense of the artist's physical and emotional investment in the painting, while simultaneously drawing attention to the material reality of the pictorial space.

Later Developments

The legacy of en plein air painting lay primarily in its influence on modern art, as it represented a rejection of Academic conventions and an embrace of artistic creation outside the studio which strongly informed modernism's radical agenda. At the same time, Cézanne's en plein air work inspired a new generation of artists, including Pablo Picasso, to undertake evermore radical analyses of the formal dimensions of a scene, while van Gogh's expressive brushwork and color palette influenced the Fauvists, Expressionists, and Neo-Expressionists. Monet's use of color influenced André Derain and other members of the Fauvist movement, as well as the Expressionist Wassily Kandinsky.

En plein air painting also remained an important technique or approach in its own right well into the early 20th century, most notably amongst the Post-Impressionist or late Impressionist artists associated with various groups in the United States and Britain. The practice declined around the start of World War I, with the exception of the California Impressionists, who continued working en plein air in art communities such as Laguna Beach and Carmel-by-the-Sea until World War II. In the 1980s, a revival of interest in the California Impressionists led to the so-called Plein Air Revival amongst a group of artists based in California. This movement, along with associated art clubs and exhibition, popularized plein air painting with a wide public, so that today it is practiced by thousands of amateur and semi-professional painters.

In the contemporary era, David Hockney is perhaps the most noted exponent of en plein air painting, though he combines it with digital techniques such as painting on an iPad. In the late 1990s, as he spent more time in the countryside in his home county of Yorkshire, he began painting the local landscape and its seasonal variations en plein air, as in works like Bigger Trees Near Warter or/ou Peinture sur le motif pour le Nouvel Age Post-Photographique (2007), a monumental work created outdoors in small sections.

Ask The Art Story AI

Ask The Art Story AI