Summary of The Flâneur

Taken from a French word, meaning to "stroll" or "loaf", the concept of the flâneur developed in Paris in the mid nineteenth century and later spread to other European cities, particularly Berlin. First and foremost a leisurely observer of urban life, a flâneur was someone that walked through a city, watching, but not participating in the things they saw. This allowed the viewer to experience and analyze city life from a detached, or external viewpoint. Despite their status as observers, early flâneurs retained and valued a sense of their own individuality and identity and many displayed flamboyant styles of self-presentation. Many flâneurs were also artists and writers who used their observations to inform their work. Particularly popular within Impressionist circles, the idea of an urban spectator underpinned the prolific streetscapes and images of popular entertainment seen in the work of artists such as Degas, Renoir, and Caillebotte, but it also influenced twentieth century art movements such as Street Photography.

Key Ideas & Accomplishments

- The term flâneur was initially associated with young men of leisure and had connotations of status, masculinity and dandyism. Consequently, many of the early works associated with the concept are filtered through a wealthy, male gaze. Later, the term was expanded to include the work of women and working-class artists and subjects, although the idea of watching and being watched remained prominent.

- The nineteenth century was a period of rapid change in terms of industrialization, urbanization, city planning, and a rise in consumer spaces. Flâneurs are seen as embodying this change, recording, reflecting, and commenting on ideas of modern life and people's changing relationships with urban areas, architecture, and each other.

- In the twentieth century, the idea of the flâneur was portrayed in new mediums and most notably informed gritty explorations of city life in Weimar Germany. Later, the concept formed the foundations for the beliefs of groups of urban artists such as the Situationists who critiqued capitalist society and sought to break down the divisions between artists and consumers.

The Important Artists and Works of The Flâneur

Place de la Concorde

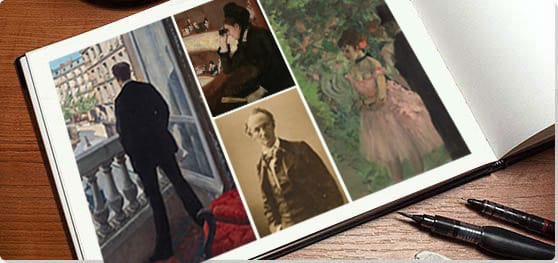

Place de la Concorde exemplifies the way in which French impressionist painter Edgar Degas communicated the ethos of the flâneur through his art. The composition is consciously asymmetric, with two children and a dog along the bottom edge, looking to the left, while one man near the right edge of the image appears to be walking off in that direction and another man is only partially in the frame to the left. A horse and carriage in the left background is also only partially visible, while the majority of the image is occupied by the empty space of the city square. Art historian Bernd Growe asserts that Degas' emphasis on the emptiness of the square serves to "highlight the vacancy through which this flâneur is passing". The flâneur in question is the man at the right of the image, Degas' friend, artist, archeologist, and patron of the arts, Ludovic-Napoleon Lepic. However, the real flâneur, the one observing and recording, unnoticed, is perhaps the artist himself.

Degas was one of the most prolific nineteenth-century Parisian flâneurs. He once stated, "I do not like carriages. One sees no one. That is why I love the omnibus. One can observe the people. We were created to observe one another". In addition to wandering the city streets, he also frequented venues for spectacle and viewing, such as the opera, cafes, the theatre, and dance studios. The paintings he made of these places offer realistic, non-idealized images which portray fleeting moments, such as ballerinas captured in unflattering poses as they ready themselves to go onstage.

Oil on canvas - Hermitage Museum, Saint Petersburg, Russia

Paris Street, Rainy Day

French painter Gustave Caillebotte was an impressionist, though he painted in a more realistic style than other members of the group. He fully embraced the role of the artist-as-flâneur, taking to the streets of Paris and sharing his observations in his paintings, like Paris Street, Rainy Day (1877). This work shows Parisians, dressed in the height of the fashion of the time, walking in the rain through the Place de Dublin, near the Saint-Lazare train station, in the district where the artist grew up. This painting was created shortly after Baron Haussmann's redeveloping and restructuring project radically changed the city's urban landscape. To account for the city's rapidly growing population, Haussmann's plans included wide, new boulevards and public squares, all paved with the same cream-colored stone, now known as Paris stone, lending the city a sense of spaciousness and continuity. Caillebotte did not fully embrace Haussmann's changes to the city, as he recognized that many working-class citizens were forced to move out of the center to the suburbs. Paris Street, Rainy Day can be understood as subtly conveying his misgivings about the "Haussmannization" of the city, as the dreary, rainy atmosphere clouds our view of the wealthy subjects depicted.

The painting is enormous, causing the figures to appear life-sized. In this way, viewers of the painting are invited to enter the frame, and are positioned as flâneurs themselves, feeling as though they, too, are walking down the street, observing passers-by. The painting also exemplifies the way in which the concept of the flâneur is linked to the sense of alienation caused by modern urbanization. All of the figures present in the image are absorbed in their own activities, and none interact with one another. As art historian Paul Smith asserts, many Impressionist artworks "involve the spectator as a flâneur...[they] appeal to the spectator to become this character. In some ways then, it is only by knowing about, and imaginatively taking on, the psychology of the flâneur that we can understand (or 'enter') many Impressionist paintings. This raises many questions about the kind of spectatorship Impressionist paintings demand".

Oil on canvas - Art Institute of Chicago

In the Loge (At the Opera)

While the flâneur is generally considered to be male, some female Impressionists, including Mary Cassatt and Berthe Morisot, created images of the flâneuse, the flâneur's female counterpart. New media artist and fine art lecturer Conor McGarrigle notes that "The gendered nature of the flâneur ...is evident in his ability as a lone male to stroll through the arcades at a leisurely pace, unnoticed and unhindered, while eschewing the temptations of consumerism. At that time, as now, this role was not afforded to all the citizens of Paris." In nineteenth-century Paris, it would not have been considered respectable for bourgeois women to wander the streets actively observing others.

In In the Loge (At The Opera), Cassatt depicts one milieu in which women were allowed to be voyeurs. Art historian Tamar Garb explains that "For men who identified with Charles Baudelaire's call for an art which represented the 'heroism of modern life,' the opera offered only one of a number of scenes of urban leisure which could be seen to embody the spirit of modernity. But for women it was one of the very few such subjects to which they had access...to the world of urban spectacle".

Cassatt was born in the United States and later moved to Paris, feeling that in that city, "women [did] not have to fight for recognition if they did serious work". In the Loge (At The Opera) demonstrates Cassatt's understanding of the gender politics of her time. The dominant figure in the frame is a female opera-goer who looks through her opera glasses. She appears to look in the direction of the stage, though we cannot be certain, she, too, may be a flâneur, watching those around her. We also cannot be certain whether or not she is attending the opera unaccompanied, as the image is cropped too closely to see if anyone sits next to her. What we can see, however, is a male figure a few balconies over who, although resting his left arm around the shoulder of his female companion, is actively engaged in peering through his binoculars at the woman in the foreground, even leaning awkwardly over the balustrade to get a better look. Cassatt, like most women, was surely no stranger to the sensation of being the object of the male gaze. What this image communicates, then, is that even at the opera, a place where women were invited to look, they were nevertheless unable to avoid being looked at as well.

Oil on canvas - Museum of Fine Arts, Boston

Die Strasse (The Street)

Art historian Julia Mitchell recognized German silent film The Street (1923), by Austrian director Karle Grune, as one of the earliest cinematic works to focus on the figure of the flâneur, and notes that, particularly in Weimar Germany, film would become the primary medium through which the concept of flânerie would be explored. In The Street, a married middle-aged man (played by German actor Eugen Klopfer) who has become bored with his life ventures into the city streets at night. Just as the typical flâneur is anonymous, Klopfer's character is nameless.

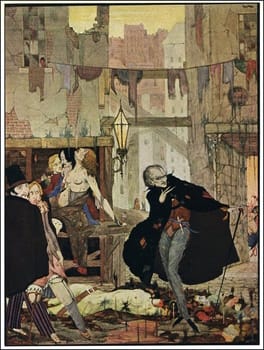

However, unlike the stereotypical Parisian flãneur, who tended to observe members of the middle and upper classes engaged in joyful recreational activities, the flâneur in The Street encounters seedier characters including sex workers and criminals. With The Street, Grune pioneered the genre of the German "street film" (also known as "asphalt film"), a cinematic genre in which the main action takes place in the city streets. Culture writer Paul Sullivan notes that the figure of the flâneur became "an ideal narrative device" for writers, filmmakers, and other artists in Germany, particularly in Berlin, which experienced rapid development in the late nineteenth and early twentieth century. Many other German films from this period portrayed the city as a foreboding and dangerous place, such as Fritz Lang's M (1931), a thriller about a serial killer who preys on children.

Silent film

Sunday on the Banks of the Marne

French street photographer Henri Cartier-Bresson is considered the master of candid photography, with the unique ability to take a photograph at what he called "the decisive moment", capturing fleeting instants often imbued with a sense of playfulness or humor. Cartier-Bresson was also the quintessential flâneur. Agnès Sire, the artistic director of the Henri Cartier-Bresson Foundation, explains that Cartier-Bresson "loved nothing so much as the grey poetry of the street" and he often wrapped his camera in black tape to make it less noticeable, allowing him to blend in to the crowd, and document his observations without being seen. He also embodied the typical role of flâneur-as-researcher, once stating "In places where I am all the time, I know too much and not enough". He captured moments he observed while walking, not only, in Paris but also in cities he visited in Canada, Spain, Italy, the Cote d'Ivoire, Mexico, and elsewhere. Some of his favorite locations to photograph, however, were along the banks of the rivers Seine and Marne in France, which were already popular subjects for Impressionist painters such as Renoir and Manet who, like Cartier-Bresson, created images of middle- and upper-class French men and women enjoying leisure activities like picnics.

Street photography emerged as a genre in the late nineteenth century as a result of technological advances that made cameras more portable and exposure times shorter. It is considered to have a special relationship with flânerie, and some of the greatest artists-cum-flâneurs were photographers such as André Kertész, Brassaï, and Eugène Atget. American writer Susan Sontag was one of the first to discuss the connection between flânerie and photography in her 1977 book On Photography. She asserts that "photography first comes into its own as an extension of the eye of the middle-class flâneur" and adds that "the photographer is an armed version of the solitary walker reconnoitering, stalking, cruising the urban inferno, the voyeuristic stroller who discovers the city as a landscape of voluptuous extremes". Media studies professor Ilija Tomanić Trivundža writes that "as a medium of expression, photography has several characteristics that are attuned to the gaze of flânerie. Most notably, the photographic camera has the capacity to capture a fleeting moment...Photography is a medium that in itself privileges surface - it reduces all social phenomena and action to their physical manifestations, to their outward appearances. It is also a medium that champions chance. The photographic camera is an ideal prosthetic device for the flâneur, not only because it enables the instantaneous recording of chance findings but also because, as a medium, it is inherently open to chance (interpretation) at the moment of viewing".

Gelatin silver print - Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York

American Girl in Florence, Italy

American photographer, photojournalist, and filmmaker Ruth Orkin grew up in Hollywood, where her mother was a silent film star. At the young age of seventeen, she became a cross-country flâneuse, biking from California to New York, and taking photographs along the way. She later travelled the world as a photojournalist. Her most famous photo series was American Girl in Italy (which was originally titled Don't Be Afraid to Travel Alone). The series is comprised of images of then-twenty-three year-old Ninalee Craig (also known as Jinx Allen) who met the photographer during a six-month solo trip around Europe. Orkin took photos of Craig at cafes, in markets, visiting landmarks, etc. This image, American Girl in Florence, Italy (1951) shows Craig walking confidently down the street, while several men standing along the sidewalk ogle her.

While this image is often understood as representing male harassment of women, Craig has insisted that "At no time was I unhappy or harassed in Europe...[The photograph is] not a symbol of harassment. It's a symbol of a woman having an absolutely wonderful time! I clutched my shawl to me because that sheaths the body. It was my protection, my shield. I was walking through a sea of men. I was enjoying every minute of it." Craig has also stated that public admiration "shouldn't fluster you. Ogling the ladies is a popular, harmless and flattering pastime you'll run into in many foreign countries. The gentlemen are usually louder and more demonstrative than American men, but they mean no harm". The image thus offers a second significance, that women can engage in flânerie in an empowered and independent way. The photos from Orkin's American Girl in Italy appeared in a 1952 photo essay in Cosmopolitan magazine titled "When You Travel Alone", which offered tips to women on "money, men and morals to see you through a gay trip and a safe one".

Gelatin silver print - Museum of Modern Art, New York

Untitled (Self-Portrait)

The modern flâneur/flâneuse is perhaps epitomized by "anonymous" street photographers like Vivian Maier. Her extensive body of photographic work was not known until after her death in 2009, and, much like Maier herself, came dangerously close to vanishing entirely into oblivion. Maier worked as a nanny for several families in the United States, and lived a solitary, reclusive life, strictly forbidding her employers or anyone else from entering her private space, and forming very few personal relationships. When Maier's photographs, which number in the tens of thousands, were found in her apartment, they revealed that she had spent decades engaged in flânerie, capturing fleeting moments she encountered in the city streets. She was apparently fascinated by the human condition as it played out in the lives of individuals from all walks of life, though her most poignant and acclaimed images are of children and the working class, people with whom she was likely able to identify.

Many who knew Maier in her lifetime believe that she would have objected to her life and work being thrust into the spotlight as it has been. Although we cannot say for certain why Maier was so secretive about her photography work, it appears that she almost never made any attempt to have her work seen by others, and many of her acquaintances had no idea that she was such an avid photographer. Some speculate that her obsessive documenting of the world through photography was pathological, more related to her hoarding tendencies than to any artistic intent. However, Maier's images also seem to indicate that she was searching for her own identity, perhaps hoping to find aspects of herself reflected in the faces of others. In fact, she took a large number of self portraits, though nearly all of them are indirect, capturing her refection in mirrors, shop windows, or car hubcaps. These curious images cannot be written off as playful experiments, as there is a great deal of evidence indicating that Maier possessed, as critic Alberto Mobilio writes, "vigorous consciousness of herself as an artist", an "acute awareness of self-portraiture's long tradition", and a solid understanding of the significance of each compositional choice she made. Thus, it could be understood that Maier, a flâneuse in the truest sense, intentionally set out to fuse her own identity and image with that of the cities in which she lived.

Photograph - Maloof Collection

The Naked City

French philosopher and filmmaker Guy Debord, co-founder of the Situationist International (SI) took the concept of the flâneur and developed it into the dérive, intended as a technique of strolling through the city, though with more critical conscientiousness, attempting to step away from their own preconceived ideas brought about by gender, class, and educational norms. The Situationists were highly aware of the effects of consumer culture and "the spectacle" of the contemporary urban landscape. They consequently planned their dérives in such a way as to avoid areas of the city most affected by consumerism. This included tourist-focused spaces such as New York's Times Square, that are dominated by advertising and billboards. Critical geographer Keith Bassett explains that "One could dérive alone, but Debord thought small groups were preferable. A dérive could last for a few hours, a day, several days, or even longer. The spatial field might be precisely delimited or vague 'depending on whether the goal is to study a terrain or to emotionally disorient oneself' by moving to unfamiliar terrain. The spatial field might be a whole city, a neighborhood or even a single building. One could explore a fixed spatial field, or if the aim was deliberate disorientation (or a 'rational disordering of the senses') rather than exploration, one might start from a 'possible rendezvous' (selected by someone who might not turn up), engage complete strangers in conversation, and incorporate various 'transgressions' (Debord gives some typically semi-serious examples, such as slipping into houses undergoing demolition, hitch-hiking through Paris in a transport strike without destination to add to the confusion, wandering in spaces forbidden to the public etc.)".

The Naked City is a psychogeographical map of Paris created by Debord, along with Danish painter and fellow SI member Asger Jorn, in 1957. Curator Gilles Rion notes that "The Naked City illustrated the central notion in psychogeography of 'centres', sorts of 'crossroads' from which several psychogeographical slopes, symbolized by arrows, can be taken". Architectural historian Simon Sadler asserts that "As a product of the anarchist-Marxist Situationist International avant-garde, The Naked City announced that modern culture was one of overlap and contingency rather than sequenced and orthogonal repetitive relation. It was a manifesto, of sorts, for revolutionary intervention in the city led by the vanguard intelligentsia, but especially with the waning of the revolutionary culture of the 1960s, it inspired an intervention in the city led by an architectural intelligentsia seeking designed rather than revolutionary events". In short, psychogeographical maps, like The Naked City, encourage a form of conscientious, active, and purposeful engagement with the city, and emphasize walking as an art form in itself.

Lithograph - Frac Centre, Orléans, France

Beginnings

Baudelaire and the Flâneur

In 1840, American author, Edgar Allen Poe published his short story The Man of the Crowd. In it, he described a man who wanders, in an unhurried fashion and without direction, through the city streets, observing the people around him. French poet Charles Baudelaire recognized Poe's "man of the crowd" as embodying a uniquely modern urban sensibility, and discussed this figure further in his 1863 book The Painter of Modern Life. Baudelaire referred to this figure as a "flâneur", which comes from the verb flâner meaning to stroll or saunter. For Baudelaire, the flâneur was a "passionate spectator" who managed to blend into the crowd unnoticed as he keenly observed the world around him.

In describing the flâneur, Baudelaire connected the figure's activity with the urban geography of the modern city. At the same time, the flâneur was seen as a figure who rebelled against the modern drive for increased productivity and obligatory engagement with capitalist modes of being. Sociologist Dale Southerton notes that "The flaneur is a key figure for understanding consumption, as he is linked with the experience of the phantasmagoria of the modern city and its commodities, leisure places, marketplaces, and shop displays". For instance, Baudelaire described the primary domain of the flâneur as the shopping arcades of nineteenth century Paris. Material Culture Studies professor Lance Winn writes that "While accommodating buyers, the arcades also accommodated those less interested in buying and more interested in observing the people and things in the city. On his leisurely stroll, the flâneur, a tourist in a world of goods brought from far places to one exotic site, could allow his mind to engender correspondences between the people, products, and images that displayed themselves in this environment....The flâneur delighted in such surrealistic scenes and resisted capitalistic productivity. One sign of their clash with the pace of modernity is the often-cited predilection of the flâneur, at the height of this life-style, for walking with pet turtles on leashes. Strolling, assessing, noting, and other non-directed activities happened only in a place of comfort".

Moreover, Baudelaire wrote of the flâneur as the prototypical modern artist. For Baudelaire, the artist-cum-flâneur was not only a "lover of universal life," but also a "mirror as vast as the crowd itself...an 'I' with an insatiable appetite for the 'non-I,' at every instant rendering and explaining [life] in pictures more living than life itself." Nineteenth-century novelist Honoré de Balzac similarly celebrated the artist-flâneur. He wrote that these privileged men "savor at every hour [the city's] moving poetry," and called the flâneur "the only happy man on earth" (supporting this claim by asserting that "no one has ever heard of a flâneur who has committed suicide".

The Flâneur in Modern Art and Literature

In his discussion of the links between modern art and flânerie, Baudelaire insisted that the modern artist must fully immerse himself in the life of the city, and become "a botanist of the asphalt". As art historian Julia Mitchell asserts, "The flâneur must be heroic in his desire to know, and in the subjugation of self that underlies this process. Above all, the flâneur must be an artist whose artistry comes from a position of both inclusion and exclusion within his socio-cultural environment". True flânerie, therefore, is not merely a hobby or pastime that one can engage in periodically, but rather a lifestyle, a holistic identity, a way of existing.

Impressionists such as Manet, Degas, and Renoir, fully embraced the role of the flâneur in their daily lives, and expressed this through their art. Sometimes they included a flâneur in their scenes of bustling Parisian life. Other times, as art historian Paul Smith writes, their paintings "are staged from the physical and psychological standpoint" of the flâneur. In other words, just as they engaged in painting en plein air when it came to landscapes, in order to immerse themselves in the scenes they were depicting, they also spent time wandering the city streets as flâneurs, leading to their exceptional cityscape paintings. French writer Jules Janin once stated that flânerie was "a wholly Parisian word for a wholly Parisian passion," and no one was more engaged in documenting Paris' golden years than the impressionists.

The flâneur artist also embraced new technologies including photography and film. The invention of the handheld camera in the twentieth century allowed it to become the tool of the flâneur and the resulting work can be seen to inform and reflect wider ideas in Street Photography. Film and photography were particularly important to the innovative art of Weimar Germany (1918-1933). Mitchell writes that "Karl Grune's film The Street (1923), Walter Ruttmann's Berlin: Symphony of a Great City (1927) and Fritz Lang's M (1931) all explore the street and observe the city, evoking a flâneuric gaze through their filmic illustration of the predominantly urban culture that produced them. Cinema became the medium through which flânerie was first translated into mass-produced art in twentieth-century society". Around the same time, explains Mitchell, "British modernist literature often used flâneuric perception as a narrative device. James Joyce and Virginia Woolf perfected the stream of consciousness technique in their writing, making their protagonists into flâneurs in classic texts such as Ulysses (1922) and Mrs. Dalloway (1925) as modern subjects who struggled to come to terms with the jarring changes wrought by the First World War".

Walter Benjamin and the Flâneur

Decades after Baudelaire wrote his account of the flâneur, German philosopher Walter Benjamin returned to the concept in an effort to better understand the cultural shifts taking place in modern urban society, in his Das Passagen Werk (The Arcades Project), which was written between 1927-40 and laid the groundwork for the beginnings of postmodern theory. He adapted the previously romanticized notion of the flâneur to fit his views of modernity, which were strongly influenced by Marxism, as well as the critical theory of German philosopher Theodor Adorno.

Benjamin's critical analysis of the flâneur focused on the figure's connection to consumerism, capitalism, class tensions, and the way in which the individual is alienated in the modern metropolis. He saw capitalist society, as well as the push for increased productivity and consumption, as a threat to the way of life of the flâneur. As critic Bijan Stephan writes, Benjamin "marked the idea [of the flâneur] as an essential part of our ideas of modernism and urbanism." His work both influenced, and was influenced by, important urban theorists/sociologists such as Lewis Mumford, Georg Simmel, Ernest Burgess, and Raymond Williams.

Concepts and Styles

The Flâneur as Anonymous Urban Observer

As arts writer Jennie Taylor explains, "The flâneur has the ability and the time to wander society while also being removed from it. His purpose is to observe society and only that: he therefore appears aimless...The flâneur, a poet in the streets, sees the world through a kaleidoscope, finds solitude in a crowd, and delights in anonymity. He treats everyday life as its own creative space. He thrives in the demands of immediacy, observing the fleeting in the moment in which they occur". Over the past two centuries, artists have both depicted the flâneur in their art, and taken on the role of flâneur, walking through the city streets, silently observing their surroundings, and presenting their observations in paintings, photographs, and more.

The Flâneur as Modern

According to cultural historian Gregory Shaya, the flâneur "was a figure of the modern artist-poet, a figure keenly aware of the bustle of modern life, an amateur detective and investigator of the city, but also a sign of the alienation of the city and of capitalism." The flâneur's role as an observer of urban life makes him inherently modern, as urbanization and increased consumption can be understood as an integral aspect of modernity. As Shaya points out, the flâneur offers insight into particular characteristics of modernity, such as the alienation caused by urban living (the flâneur always maintains a psychological distance from those around him), the effects of capitalism on individual experience (with the increased social drive for productivity, the flâneur loses the ability to stroll the streets slowly and observe others doing the same), and the effects of urbanization on class divisions (only a man of means has the luxury of engaging in flânerie).

The Flâneur as Male

Historically, the flâneur has been exclusively male. This is because, as author Deborah Parsons explains, "the opportunities and activities of flânerie were predominantly the activities of the man of means", while aimless, solo wandering and voyeurism were considered inappropriate activities for well-to-do women. This resulted, for example, in what art historian Paul Smith recognizes as "the implication that Impressionist paintings were done for men," that is, for the male gaze specifically. Nevertheless, many women (including female artists such Polish-German photographer Germaine Krull, German-French photographer Gisèle Freund, and Austrian-American photographer Lisette Model) have engaged in flânerie, embodying the role of the flâneuse. However, due to differences in gender norms, as feminist writer Gabby Tuzzeo explains, the flâneuse "is not a female flâneur but an entirely separate concept. The Flâneuse acknowledges that women experience and explore cities in a completely independent and unique way". For example, a flâneuse will, more often than a flâneur, be viewed as rebellious, radical, or even transgressive.

The Flâneur as Parisian

As comparative literature scholar Martina Lauster writes, "The flâneur was originally a distinctly Parisian type, though he quickly spawns British and German counterparts". It was in the streets of the newly-redesigned Paris that the flâneur came into being, and his distinctly Parisian character was reinforced by the strong identification of the French impressionists with the figure of the flâneur. However, more recently, as Korean artist Changnam Lee notes, "The ever-expanding influence of flânerie goes beyond the scales of geography...As living conditions become more fluid, the regional flâneur as a 'priest of genius loci' has transformed into the trans-regional flâneur".

Later Developments

The Flâneur since Benjamin

Over the past century, the figure of the flâneur has continued to influence scholarship and artmaking that relates to the themes of city life and the psychological effects of urbanization. For example, author Edmund White uses the concept of the flâneur to identify some of the unique qualities of American culture, writing that "Americans are particularly ill-suited to be flâneurs", due to their "relentless urge toward self-improvement", their "need to constantly work", and their "rigid agendas and itineraries".

Guy Debord, The Situationists, and Psychogeography

French Marxist theorist Guy Debord was a founding member of the Situationist International (SI), a group of artists and activists who worked from the 1950s to 1970s to challenge what they saw as the social and psychological effects of increasing consumerism and "spectacle-worship" in contemporary Western society. The Situationists were heavily influenced by Debord's concept of psychogeography, which he defined as "the study of the precise laws and specific effects of the geographical environment...on the emotions and behavior of individuals."

The Situationists developed the concept of flânerie into the technique of the dérive. As critical geographer Keith Bassett explains, the dérive was intended to be "more than just strolling; it was a combination of chance and planning, an 'organized spontaneity', designed to reveal some deeper reality to the city and urban life...On a dérive one tried to shed class and other allegiances and cultivate a sense of marginality. Dérives thus tended to avoid the more obvious tourist areas, which pandered to crass appetites for ultravisible urban spectacles".

Useful Resources on The Flâneur

- Flâneur: The Art of Wandering the Streets of ParisBy Federico Castigliano

- The Flâneur: A Stroll through the Paradoxes of ParisOur PickBy Edmund White

- Walking in Berlin: A Flâneur in the CapitalOur PickBy Franz Hessel

- The FlâneurOur PickBy Keith Tester

- Flâneuse: Women Walk the City in Paris, New York, Tokyo, Venice, and LondonBy Lauren Elkin

- The Art of Flâneuring: How to Wander with Intention and Discover a Better LifeBy Erika Owen

- The Painter of Modern Life and Other EssaysBy Charles Baudelaire

Ask The Art Story AI

Ask The Art Story AI