Summary of French Art

It is difficult to imagine a nation for whom art plays a more vital role in its collective consciousness than France. French art has an enviable heritage that dates back to the Middle Ages when it created some of art history's best examples of Romanesque and Gothic art and architecture. The period of the French Renaissance was proudly represented by the court painter Jean Clouet, while by the mid-17th century, Nicolas Poussin had assumed the mantle of the father of the French classical tradition. The charming frivolity of Rococo, which for many was the first purely French art, duly gave way to the age of Enlightenment and the emergence of Neoclassicism, Romanticism, and Realism introduced to the world artists of the stature of Jacques-Louis David, Eugène Delacroix, and Gustave Courbet.

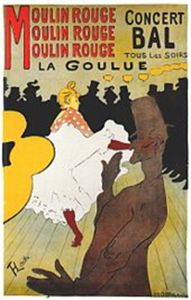

But by the beginnings of the 20th century, Paris had become to modernism what Florence had been to the Renaissance. The French capital was the stage for the greatest period of experimentation in art history and the bohemian café life of Montmartre acted as a magnet for avant-garde artists and writers from around the world. Under this environment, Impressionism duly became Post-Impressionism, Fauvism gave way to Cubism, while Dada evolved into Surrealism. And through this monumental period in art history, the pantheon of world artists would induct French names including Édouard Manet, Claude Monet, Pierre-Auguste Renoir, Auguste Rodin, Berthe Morisot, Henri Matisse, Georges Braque and Marcel Duchamp into its hall of fame. By the mid-20th century New York had replaced Paris as the epicentre of modern art, but France has continued to be represented on the world stage on contemporary art by the likes of Jean Dubuffet, Yves Klein, and Louise Bourgeois.

Key Ideas & Accomplishments

- Light-hearted and charming, but with more than a hint of eroticism, the Rococo style was exemplified by Jean-Antoine Watteau and his Fête Galante (outdoor entertainment) paintings. Works such as Pleasures of Love (1718-19), featured elegant figures dressed in pastel colors, engaged in rituals of courtship against a backdrop of a rich and pleasant outdoor setting. With the onset of the new age of Enlightenment thinking, critics such as the philosopher Denis Diderot, rejected Rococo art in favor of a "nobler art" (which would soon take the shape of Neoclassicism). Nevertheless, the Rococo style stood (before the arrival of Impressionism) as the first quintessentially French art.

- Following the excesses of the Baroque, and the "folly" of Rococo, Neoclassicism emerged as the artform that could accommodate the spirit of either conformity or revolution. Indeed, by drawing on the rules of classical art, artists could "return" to the timeless and universal virtues on which European enlightenment were founded. More than any other French artist of his day, it was the pro-revolutionary painter Jacques-Louis David who exemplified the French Neoclassical style. With paintings such as The Death of Marat (1793) he represented one of the leaders of the French Revolution lying dead in his bathtub, in a composition that recalled classical paintings that represented the crucifixion of Christ.

- Romanticism is a tendency that one typically associates with landscapes and artists seeking to capture the true - or "sublime" - majesty of nature on canvas. In France, however, Romanticism took on a different bent by bringing the same sort of pictorial drama to contemporary social themes. Delacroix, who painted one of France's most iconic masterpieces, Liberty Leading the People (1830), emerged as the leader of French Romanticism. His paintings displayed a strong dramatic intensity, and he was greatly admired by the illustrious French poet, Charles Baudelaire, who was especially impressed by Delacroix's handling of color and his ability to use his palette to communicate sensations that were beyond the reach of words and poetry.

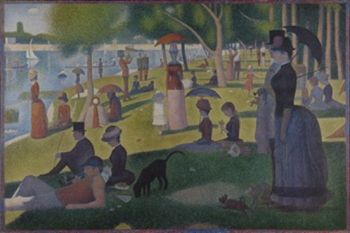

- When one thinks of the world's most iconic national schools of painting, then one probably thinks first of the Italian Renaissance and French Impressionism. As historian Kate Heveles put it, "French art in the popular imagination is often characterized by the dreamy, dauby landscapes of the Impressionists". The Impressionists had in effect announced a new epoch that liberated art from the "stuffy" authority of academic art and, using vivid colors, and with a focus on everyday subjects, painted en plein air (on location rather than in a studio), set the scene for a modern art fit for a modern age.

- Thought by many to be the most important modern artist of all, Marcel Duchamp was a true iconoclast. His impact on the development of contemporary art is impossible to overlook. Best known for his "readymade" sculptures, Fountain (1917) - an upturned urinal that he signed "R. Mutt" and dated in the fashion of an original artwork - sent shockwaves through the contemporary artworld. Thought by many at the time to be a practical joke, Duchamp later defended his work by saying "I was interested in ideas, not merely in visual products". After Fountain, sculpture no longer insisted on the use of traditional modeling materials and subject matter. Duchamp had, in effect, pre-empted the rise of Conceptual Art, Minimalism, and Pop Art.

Overview of French Art

Historian E H Gombrich wrote: "It took some time before the public learned that to appreciate an Impressionist painting one has to step back a few yards and enjoy the miracle of seeing these puzzling patches suddenly fall into place and come to life before our eyes. To achieve this miracle, and to transfer the actual visual experience of the painter to the beholder, was the true aim of the Impressionists."

The Important Artists and Works of French Art

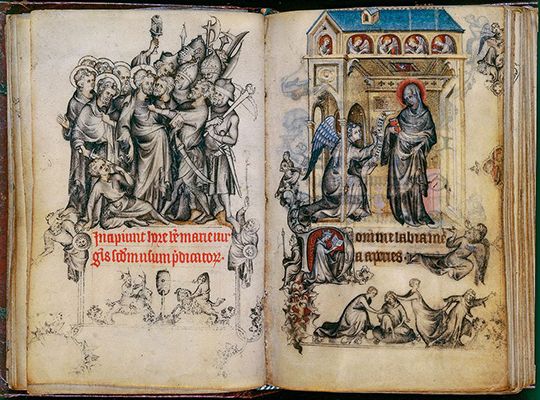

Hours of Jeanne d'Evreux

Book arts was a popular feature of French Gothic art. Illuminated manuscripts and small books of prayers, such as the books of hours, were created with meticulously detailed depictions of religious scenes. These were usually commissioned by wealthy individuals for private devotion, but other Gothic manuscripts were larger in size (able to accommodate the four books of the gospel) and were produced primarily for convents, monasteries, and churches. While many of the artisans who created the illustrations remain unknown, some began to gain recognition for their work including Jean Fouquet, Master Honoré, and Jean Pucelle.

Perhaps the finest examples of a medieval book of hours, Pucelle's Hours of Jeanne d'Evreux, was a private devotional book made for the queen of France. It contains prayers to be said on a given hour of the day. This illuminated manuscript, which measures less than four inches in height, consists of 209 pages of text and images, with twenty-five pages devoted solely to illustrations. According to the Metropolitan Museum of Art, Pucelle's detailed artworks include "images from the Infancy and the Passion of Christ and scenes of the life of Saint Louis, the queen's ancestor. In the margins, close to 700 illustrations depict the bishops, beggars, street dancers, maidens, and musicians that peopled the streets of medieval Paris, as well as apes, rabbits, dogs, and creatures of sheer fantasy".

Pucelle who was the leading illuminated manuscript artists of the Middle Ages and a member of the group of artists who became known as the School of Paris. While the monied classes were the only group able to commission such books, the fact that this was made for the queen accounts for the book's particularly fine detail and ornamentation. Of special interest is Pucelle's depiction of the life and death of Christ on facing pages. On this set of pages, for instance, the left page shows a scene of Christ's betrayal by Judas, while on the right, Mary is being visited by an angel who tells her she will carry the Christ child. In this way the purpose of Christ's birth is visually linked always to his sacrificial death as a way of forgiving man's sins; a visual assertion of the fundamental tenet of Christianity.

Grisaille, tempera, and ink on vellum - Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York

Notre Dame de Paris

The Notre Dame de Paris ("Our Lady of Paris"), one of the most recognizable cathedrals in the world (and the cathedral of the Catholic archdiocese of Paris, which houses the official chair -"cathedra" - of the Archbishop of Paris), and one of the French capital's most recognizable and visited landmarks, is an exemplar of French Gothic architecture. The towering cathedral had thinner and higher walls than the Romanesque buildings that preceded it, but these proved highly susceptible to stress fractures. Notre Dame is thought to be one of the first buildings in the world to incorporate flying buttresses (arched exterior supports) as a means of surmounting this problem. The long period of construction did, however, mean that the building, with its vast displays of artworks, sculpture, and stained glass, introduced emerging ("post-Gothic") styles such as naturalism.

The "first" art historian, the Italian Giorgio Vasari, dismissed Notre Dame as a "barbaric" insult to the austere Romanesque style of architecture that preceded it. It was not a view shared (some 400 years later) by the famous historian E H Gombrich, however. He wrote "the walls of these buildings were not cold or foreboding [as they were in the Romanesque style]. They were formed of stained glass that shone like rubies and emeralds. The pillars, ribs and tracery were glistening with gold. Everything that was heavy, earthy or humdrum was eliminated. The faithful who surrendered themselves to the contemplation of all this beauty could feel that they had come nearer to understanding the mysteries of a realm beyond the reach of matter". He concluded that the magnificent façade of Notre Dame "is so lucid and effortless in the arrangement of its porches and windows, so lithe and graceful the tracery of the gallery, that we forget the weight of this pile of stone and the whole structure seems to rise up before us like a mirage".

Paris, France

Portrait of François I as St John the Baptist

Clouet was one of the most important French Renaissance masters and a court painter to King François I. Clouet painted several generic portraits of the King, but this is one of the most interesting because of his decision to align the King with such a key biblical figure (John the Baptist preached the imminence of God's Final Judgment and is revered in Christianity as Christ's predecessor). The King is not then dressed in his usual royal finery, but rather in a plain shepherd's robe. Intended to mimic the part of John, the King holds a lamb and a simple wooden cross while a bird (almost obscured in the dark background of the painting) observes the King from its perch.

King François was a progressive monarch who managed to persuade Leonardo da Vinci to come to France to work freely in his court. An important example of the French Renaissance style, here Clouet has been influenced by da Vinci's portrait of the saint in his version of the painting. In da Vinci's version, however, John points upward as if to heaven whereas here Clouet has the King point downwards to the lamb's head making reference perhaps to Christ's role as the "lamb of God". The inclusion of objects and the colorful robe nevertheless contributes a hint of regal elegance to the work which was in keeping with French Renaissance portraiture. There is more to this portrait in that it makes a statement about power that can be interpreted in fact as propagandist. Art as a vehicle for propaganda was by now well established (dating to the art of Ancient Egypt). Here the suggestion is clear in that the King's connection to God validates his given "right to rule".

Oil on canvas - Louvre Museum, Paris

The Abduction of the Sabine Women

Nicolas Poussin's finely detailed painting is a visual recreation of the mythological story detailing the abduction, and eventual rape, of the Sabine women who had attended a wedding at the invitation of the neighbouring Romans. Poussin has captured the start of the abduction which was launched by Romulus who is shown here giving the signal to attack by the lifting of his red cloak.

The women in this painting contort their bodies as they try to escape the Romans who simultaneously use swords to fight off the Sabine men who are attempting to stop the kidnapping.

The elevated drama of the scene helped popularize the Baroque style within French painting. However, the mythological subject matter - the Roman style of dress of the figures and architectural background in which the setting is placed - confirm Poussin as the master of the French Classical tradition (and saw him hailed in some quarters of the Académie Royale de Peinture et de Sculpture as the "French Raphael"). According to author Valentin Grivet, "in contrast to Mannerism and Baroque currents, Poussin represented an orderly style which he imitated the perfection of ancient ideals [while his] figures, frozen in their movements seem to have sprung from theatre scenes". Poussin's classical influence (he spent large parts of his career in Rome) would then moderate the theatrical leanings of the Baroque through a distinctly French style that became known as Baroque Classicism.

Oil on canvas - Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York

Palace of Versailles (Hall of Mirrors)

The Palace of Versailles is an ostentatious former royal residence in the south-west suburb of Paris. The town of Versailles itself was no more than a village settlement before it became a seat of royal power. By the time of the French Revolution of 1789 (during which, surprisingly perhaps, the Palace avoided any serious damage) Versailles had grown to a population to more than 60,000, which made it one of the most densely populated urban areas in France.

Louis XIII was initially attracted to the area because of its hunting potential. He bought up land and built a chateau which he used as a base for hunting trips at the beginning of the century. The chateau was however not much more than a hunting lodge and it was his heir, Louis XIV, the "Sun King" as he was affectionately known, who transformed Versailles into the seat of France's government. He ruled for 72 years and during that time added to Louis XIII's chateau by building a palace containing north and south wings, and buildings designed to house ministries.

The art historian Tea Gudek Snajdar writes: "The most important message Louis XIV sent through the architecture of Versailles was his ultimate power [...] He is an absolute monarch, untouchable and distant. But, even more than that, he is the Sun King. That symbolism of the Sun King is very visible in the architecture of the Versailles. The painter Lebrun, who designed the iconographic program of the Palace, focused paintings, sculptures and the architecture to one goal only - celebrating the King". The Palace is also famous for its Baroque gardens that contained many sculptures, pressurized water fountains (of which the King was especially proud) and even a grand canal that "ran about a mile long, was used for naval demonstrations and had gondolas, donated by the Republic of Venice, steered by gondoliers".

Versailles is often cited as the apex of an overlap between the French Baroque and Rococo era. But as Snajdar writes, "It's very different from, for example, Italian baroque architecture, which served as an inspiration for other European countries during that time". She adds that a French palace that mimicked Italian baroque architecture "would have gone against [the King's] sense of absolutism" and the belief that "he is at the center of everything". She adds that "it was vital to him to enhance France's status in Europe, not just by military feats but in the arts as well. For instance, when the Hall of Mirrors was built, mirrors were usually imported from Italy at a great cost. Louis XIV wanted to show that France could produce mirrors just as fine as those produced in Italy, and consequently, all the mirrors of that hall were made on French soil".

Versailles, France

The Swing

A beautifully dressed woman in a gathered pink gown and hat is depicted seated on a swing in a wooded, flower-filled garden. The man behind her pulls the swing with two ropes seemingly oblivious to the fact that a second man lays in the bushes with a clear view of the girl's legs and bare left foot which is left exposed as her pink slipper is propelled through the air. The dog behind the swing, and the statues in the park, also seem to be watching the scene. On the far left, a cupid looking down at the woman with a finger to his lips connotes a gesture of secrecy, while two embracing baby angels look on the scene with fascination (and perhaps some embarrassment).

This work provides an important example of the French Rococo art movement which featured scenes of frivolity and leisure of the country's upper class. There was a certain scandalous element to this work with its depiction of forbidden dalliances and questionable conduct among the subjects which were often at the heart of Rococo paintings. For people of high societal rank (indicated here by their clothing) it would have been inappropriate for a man to look at a woman in such a way in public. The ability to create light, colorful works which are counter to the playfully sensual subject matter depicted was something at which Fragonard excelled. Even the extended title of this piece, The Happy Accidents of the Swing, nods to the subject matter asking the viewer to question whether any of this is an accident or if in fact the woman and the man in the bushes have orchestrated the entire event (a story that is more likely given that the painting was created for Baron de Saint-Julien who commissioned a work that would feature his mistress being pushed by a duped bishop so he himself could be pictured observing her body).

Oil on canvas - Wallace Collection, London

The Death of Marat

David's painting features one of the leaders of the French Revolution Jean-Paul Marat, his head wrapped in a turban, lying dead in his bathtub. His right arm and head are positioned leaning out over the tub while on the floor by his arm is the knife used to kill him. The means to his demise is held in his hands; a letter used by his killer to enter his home. In front of the tub in the right foreground is a writing desk on which rests pages of his work.

Perhaps more than any other painting in David's oeuvre, this work shows his ability to capture the spirit and heart of the French people as they struggled to assert their rights through revolution. This feat is made more impressive in that it does not depict a battle scene. Rather, David gives us a single figure who has died for his cause, martyred for his country in a pose, not unlike Christ's lifeless body as he hangs crucified on the cross. This biblical reference anchors the work firmly within the Neoclassicism tradition.

Art historian, Dr. Jeanne S. M. Willette, writes: "Dating from 1760 to 1800, the Neoclassical period begins with an air of expectancy, as though an era is awaiting a Messiah. The co-author of the Encyclopédie, Dictionnaire Raisonné des Sciences, des Arts et des Métiers, Denis Diderot yearned for the artist who could correct the excesses of the Baroque and the decadence of the Rococo, but he did not live to enjoy the work of the artist, who would inflict upon these old styles the coup de grâce, Jacques-Louis David. Neoclassicism is more than a simple shift in artistic style or in audience taste, the style became a vehicle for conformity or rebellion, for the erotic of the political, depending on the artist in question. The fact that this ancient style proved to be so flexible and contradictory is explained by its placement in time - in the midst of vast economic and social changes, with intimations of a 'return' to the foundations of European culture so that a new society could be built upon the old values. Neoclassicism was ideally suited to a new 'grand' style that could supersede the Baroque and re-inject a new seriousness into history painting".

Oil on canvas - Musées Royaux des Beaux-Arts, Brussels

A Flood Scene

There was a period of transition between Neoclassicism and Romanticism that can be seen in the paintings of a former pupil of David, Anne Louis Girodet. He moved away from classical antiquity in favor of works that were of a more dramatic and emotionally charged nature. Girodet won the prestigious Prix de Rome award that saw him embark on a five-year sojourn around Italy. He returned to Paris in 1795 when he confirmed his reputation with two key works, Portrait of Madame Lange as Danaë (1799), and A Flood Scene (1806). The former was in fact an act of revenge (Girodet had a reputation as a fiery figure) on Madame Lange, a famous actress. His original portrait was not to her liking, leading her to withhold her fee, followed by a demand the portrait be removed from public display. An enraged Girodet painted a second, satirical, portrait based on the Greek legend of Danae (one of the mortals loved by Zeus). The painting is rich in symbolism with Danae/Lange's cracked mirror connoting her inability to see herself for the true woman (as Girodet saw her) that she was: vain, adulterous, and avaricious.

Having already gained acclaim (and notoriety) for his Danae/Lange portrait, Girodet continued his search for individualism by painting what was perhaps his most important work. A Flood Scene was not (as it might at first appear) a biblical narrative but was rather a scene conjured from his own vivid imagination. The painting is monumental in scale (441 by 341 cm) and its high drama and disturbing imagery caused a sensation at the 1806 Salon. Girodet's dramatic subject matter, unusual coloring, and his highly emotional treatment of his material went against the reason and order of the Enlightenment artists and saw him aligned to the burgeoning Romantic movement.

Oil on canvas

Liberty Leading the People

Delacroix's most famous painting features individuals of various ages charging across a battlefield strewn with dead bodies. In the center, a bare-breasted female figure, bearing a rifle in her left hand, raises her right arm proudly displaying the French national flag. To her right are two men; one in a white shirt raising a long knife while running; the other, a formally dressed man with black jacket, tie, and top hat holding a rifle. To the woman's left is a young boy brandishing two pistols, while in the far distance, obscured by the smoke and the devastation of battle, is the outline of city buildings.

Here the subject is a short-lived revolt against the French monarchy. Rich in symbolism, the unity of classes is shown in the bourgeois fighting next to the proletariat under the colors of Liberty's national flag. Embodying the Romanticism spirit of which Delacroix was the leader, this painting is full of dramatic movement and beautifully captures the patriotic spirit of the event without distracting from the reality of the situation. According to critic Jonathan Jones, "Delacroix has painted the hysterical freedom and joy of the revolution. His painting survives as revolution's most charismatic visual icon. And yet it is not naïve. Death is part of the glamour, and there is sickness at the very centre of progress. Romanticism is not an optimistic art. If Delacroix's painting understands the seduction of revolution better than any other, it also acknowledges the violence that is inseparable from that belief in total change and the rule of the crowd".

The great poet Charles Baudelaire was one of Delacroix's most vocal supporters, describing him as "decidedly the most original painter of all times, ancient and modern". Baudelaire was taken by the social commentary in Delacroix's work, but he was especially impressed by Delacroix's handling of color which in Baudelaire's view illustrated the "correspondences" between the poet and the painter. While the poet was challenged in their ability to describe colors, the painter was equally curtailed in their ability to capture non-visual emotions and sounds. Baudelaire's appreciation of Delacroix was based on the idea that he was a supreme colorist who could use his palette to capture and convey unspoken sensations.

Oil on canvas - Louvre, Paris

The Romans during the Decadence

The subject of Thomas Couture's large-scale History Painting is the moments following a Roman orgy with a group of men and women depicted in various stages of undress. It demonstrates that academic painting in the mid 19th century could also address itself to divisive political themes, albeit in a less overt way than Romantic painters such as Théodore Géricault or Eugène Delacroix.

That the figures are from the past can be seen in the Roman statues and architecture that form the backdrop. Couture, an established Academy history painter, depicts a scene after the orgy has taken place, leaving the viewer to imagine what has happened before. According to author Michael Fried, "Couture's painting is deliberately not a representation of violent or ecstatic activity. The few incidents of that kind that there are take place only at the fringes of the main group, whose members by and large are shown either in repose or performing the simplest of actions, e.g., holding a goblet, pouring wine, standing up. This suggests that Couture's choice of moment (in the broadest sense) was partly motivated by the desire to constrain action and expression within strict limits, and by so doing to minimize the obviousness of their inevitable theatricalization".

While this painting may be set in Ancient Rome, it was meant as a blunt metaphor for the extravagances and vulgarity (as Couture saw it) that was at the heart of the French government. As the Harvard Art Museums describes, "a trope of Roman literature was to lament the decay of moral standards, comparing the noble past with the debauched present, often using the excesses of banqueting to illustrate the point. Inspired by the first-to-second-century CE satirist Juvenal, Couture contrasted the orgy in the foreground with the dignified sculptures in the background as an allegory for the degeneration of his own time". A further example of art making as "political statement", Couture's painting was implicitly endorsed by the French establishment when it was exhibited in the annual Academy salon.

Oil on canvas - Musée d'Orsay

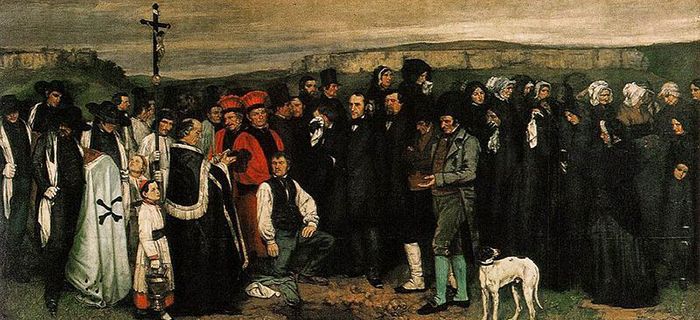

A Burial at Ornans

Gustave Courbet's painting features a scene from the funeral of his great-uncle in the town of Ornans. It is the realistic way in which all the figures were depicted in the French countryside that is perhaps most striking about the work and, according to author Magda Michalska, "because Courbet painted them all as they really were in life, without any idealisation or masking their features to make them anonymous - anyone from Ornans would recognize them, or even find themselves on the canvas. We can see Courbet's mother and three sisters (Juliette covers her mouth, Zoé's face is entirely covered by cloth, and Zélie is on the far right)".

The master of what became known as the French Realist movement, this painting was shocking when it debuted. According to Michalska, "the critics hammered the work for several reasons. Firstly, for its size [...] which should have heralded it as a history painting. Which according to the canon should present a solemn historical or religious theme, as only such genre scenes deserved such a grand scale. Courbet instead presented normal people at a funeral, many of which were of a lower class, which outraged the high-class critics and Salon-goers even more, as they couldn't stand the characters' ugliness and ordinariness. Secondly, the painting was initially interpreted as anticlerical, because even the clergy were depicted as ugly. Yet later, this interpretation was overturned - in the end, Christ on the cross towers over the entire scene, giving us solace and hope for salvation. Thirdly, viewers didn't like Courbet's technique, the thickly layered paint and the dark tones dominated the scene. Somebody said that Courbet painted pictures like somebody blacking their boots".

Courbet said of his art: "I hope always to earn my living by my art without having ever deviated by even a hair's breadth from my principles, without having lied to my conscience for a single moment, without painting even as much as can be covered by a hand only to please anyone or to sell more easily".

Oil on canvas - Musée d'Orsay, Paris

Le Déjeurner sur l'herbe

Édouard Manet's painting Le Déjeurner sur l'herbe features two bourgeois Parisian men seated in the middle of a wooded park. An overturned basket full of fruit, cheese, and bread, implies that a picnic has taken place while the woman who sits next to the two men, naked with her clothes in a pile behind her, indicates a sexual liaison. Another woman, clothed in nothing but an undergarment, washes in the stream located a few yards behind the men. The style in which Manet rendered this painting was not initially popular. The broad, thickly applied, brushstrokes and the focus on light and the outdoor setting lacked the strict formality of the French Academic landscapes which had been popular for decades. Still, it would inspire the first great modern art movement in France; Impressionism and thus ranks as one of the most important works in the history of French art.

When Manet submitted this painting as his entry for the Paris Salon of 1863, it was rejected due to its outrageous vulgarity. Undeterred, Manet displayed it in the now infamous Salon des Refusés with other rejected works by artists who would soon become the first generation of France's great modern painters. The direct way that the naked woman stares out at the viewers without the slightest hint of shame is what jurors found so objectionable. While prostitution was legal in France at the time, this painting shone a light on the "oldest profession" in a way that many were not yet ready to acknowledge. Manet was a close friend of the great French poet Charles Baudelaire. Indeed, it was through Baudelaire's encouragement that Manet - a kindred spirit who was reviled for his infamous collection Les Fleurs du Mal just as much as Manet was reviled for his paintings - fulfilled the poet's vision of the true painter of modern Parisian life.

Oil on canvas - Musée d'Orsay, Paris

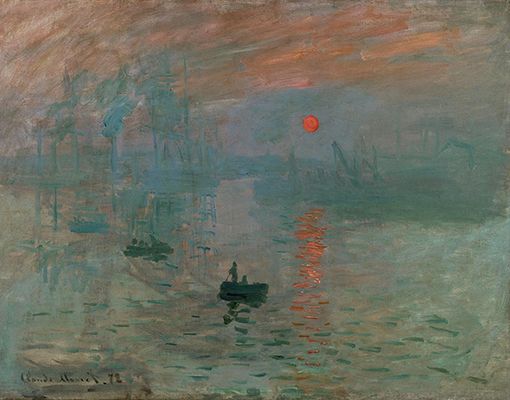

Impression, Sunrise

While small in circumference, it is the vibrant orange sun rising in the sky that dominates Monet's painting. The orange reflection of the sun's rays is seen in the gray water of the port of Le Havre. On the water float a collection of small boats, the closest of which is a rowboat carrying two figures in the center foreground. It is often argued that this work introduced modern art to the sceptical French public when it was displayed at Paris exhibition of Impressionist works in April 1874. As author Elena Martinique describes, "painted with loose brush strokes, it is meant to only suggest the scene rather than to mimetically represent it. The colors are very restrained, and the paint is applied in thin washes. Layering gray in different tones, the artist provided depth despite imprecise details [...] Monet titled the piece just before the exhibition, referring to its hazy painting style".

The critics picked up on the painting's title and tried to insult Monet by ridiculing the idea that his new style of applying paint to the canvas was merely leaving an "impression" of an object (rather than a realistic depiction). This slight backfired, however, and according to Martinique, "while they intended to mock the new movement, these critics actually helped propel Impressionism" and Monet emerged as the new movement's de-facto leader.

Oil on canvas - Musée Marmottan Monet, Paris

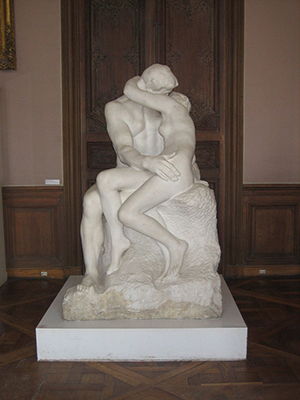

The Kiss

Auguste Rodin's masterpiece features a man and a woman locked in a passionate embrace. As described by the Musée Rodin, this sculpture, "originally represented Paolo and Francesca, two characters borrowed [...] from Dante's Divine Comedy: slain by Francesca's husband who surprised them as they exchanged their first kiss, the two lovers were condemned to wander eternally through Hell". The sculpture was originally intended to feature on the lower left door on Rodin's monumental bronze sculpture The Gates of Hell (1899) but, as Musée Rodin confirms, "Rodin decided that this depiction of happiness and sensuality was incongruous with the theme of his vast project. He therefore transformed the group into an independent work and exhibited it in 1887. The fluid, smooth modelling, the very dynamic composition and the charming theme made this group an instant success. Since no anecdotal detail identified the lovers, the public called it The Kiss, an abstract title that expressed its universal character very well".

Rodin's sculpture helped to deliver French sculpture into the modern realm. Prior to Rodin there had been a strict formality to French sculpture often depicting Christian religious figures or portrait busts of royalty and important French citizens. As author Silka P states, "Taking away the hard outline of traditional production, Rodin approached sculpture in a realistic style. Taking a leap from an idealized human form of the past, Rodin stripped away many narrative references to the classical myth that were still attached to the academic sculpture of the late 19th-century. Instead of focusing on the representation of gods or muses, Rodin opted for the celebration of the lifelike figures distinctly reflecting the newly shaped attitudes of love, thought, and physicality. Producing rougher, more unfinished surfaces, Rodin mirrored the constant motion of the modern times".

Marble - Musée Rodin, Paris

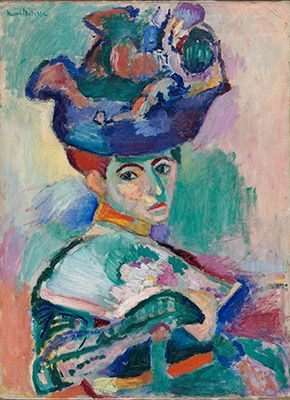

Woman with a Hat

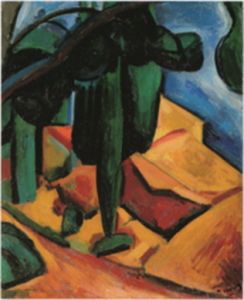

A formally dressed woman, the artist's wife Amelie, dominates Henri Matisse's canvas. Seated in a chair, she looks out at the viewer over her right shoulder with an absent expression on her face. Her dress and her large hat are brightly colored as is the abstracted background against which she is placed.

This work launched the Fauvist movement. According to author Margaux Stockwell, "Woman with a Hat marks a moment of stylistic transition in Matisse's oeuvre, from a more classical controlled style towards his characteristic expressive style. Woman with a Hat was first exhibited at the 1905 Salon d'Automne in Paris, an exhibition that was surrounded by controversy as Matisse and his contemporaries' avant-garde style was met with much criticism. The collective works of Matisse and the other exhibiting artists were labelled by critics 'Les Fauves', meaning the wild beasts, due to the seemingly untamed, unruly colors that filled the canvases". Like the Impressionists' showing at the Salon des Refusés some 40 years earlier, Matisse and his group refused to be put off by the criticism and turned the critics' insult into a spur that saw the group continue to paint in their unique style under the Fauvist banner.

Oil on canvas - San Francisco Museum of Modern Art, San Francisco

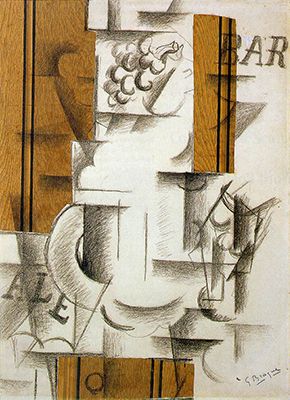

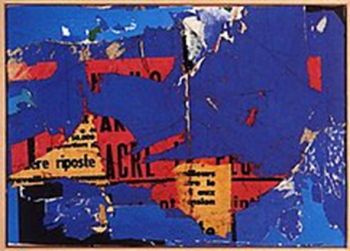

Compotier et verre (fruit dish and glass)

As the earliest Cubist papier collé (a collage formed of pasted papers), Braque's work marked a decisive break in the move from the overtly complex (and serious) Analytic Cubism towards what became known as Synthetic Cubism (reflecting a technique that "synthesised" different materials). Braque later told the story of how he was strolling through the streets of the nearby city of Avignon when he spotted rolls of faux bois (fake wood-grain) wallpaper on display in the window of a hardware store. Braque began experimenting by pasting the faux bois into a series of charcoal drawings with lettering.

On the one hand, Compotier et verre might be considered a Cubist rebus (a puzzle containing pictures and letters). "Hidden" within its horizontal and curvilinear forms, we can clearly make out the drawer of a table (represented through the circular doorknob) and some grapes, while the lettering relates explicitly to a bar serving alcohol. But by bringing scraps from the material world into the artificial world of the drawing, Braque asks the viewer to consider the texture and material of the work just as much as the image's content. There is a clear separation between the shapeless color and the drawing in the work with the former becoming a thing in its own right. Braque commented later that "Colour came into its own with papiers collés [...] with these works we [he and Picasso] succeeded in dissociating colour from form, in putting it on a footing independent of form, for that was the crux of the matter".

Charcoal and cut-and-pasted printed wallpaper with gouache on white laid paper; subsequently mounted on paperboard - Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York

Fountain

Duchamp's Fountain consists of a urinal, which he provocatively signed "R. Mutt" along with the year 1917. Considered to be the most important of his "readymade" sculptures, the work caused controversy when it debuted. According to author Jon Mann, "Duchamp, wanting to submit an artwork to the 'unjuried' Society of Independent Artists' salon in New York - which claimed that they would accept any work of art, so long as the artist paid the application fee - presented an upside-down urinal [...] The Society's board, faced with what must have seemed like a practical joke from an anonymous artist, rejected Fountain on the grounds that it was not a true work of art. Duchamp, who was a member of that board himself, resigned in protest".

Notwithstanding the initial controversy, the effect of the sculpture was profound on the development of modern art and provides further evidence of France's impact on modern art with these works helping to launch the Dada art movement. According to author Silka P, "art's story could not be told if [...] Marcel Duchamp is not mentioned. As a revolutionary figure, Duchamp is considered as one of the most influential artists. His focus on the idea or a concept above the choice of the material resulted in the original idea of the sculpture as an assemblage object. His famous readymades best illustrate this view which Duchamp shared with the rest of his avant-garde contemporaries. Sculpture no longer needed to be made with the use of traditional modeling and the move from tradition resulted in the birth of abstract sculpture". Duchamp defended his readymades by saying "I was interested in ideas, not merely in visual products". In this respect, Duchamp had pre-empted the rise of Conceptual Art, Minimalism, and Pop Art.

Porcelain - Tate Modern, London

Portrait of Louis Aragon

The poet and novelist Louis Aragon (and a national war hero) was, with André Breton and Phillipe Soupault, a founder of the Surrealist movement. Masson's discombobulated portrait stretches Aragon's image across the picture plane. The sketch is highly gestural, but Masson has given us a point of detail in the center where some of the "airborne" lines appear to congregate. The head of Aragon, meanwhile, is constructed with loose marks as if it is about to disappear in a "puff of smoke". We can spot ambiguous forms - a foot, a button perhaps - which then fall out of focus and disintegrate into lines that send the viewers' gaze off in all directions. The name "Louis Aragon" is written into the drawing and this, coupled with the use of black ink on plain white paper, is evocative of the practice of writing, which alludes to Aragon's career as well as the mutability of Surrealism: from poetry and prose to the pictorial arts.

The two men struck up a close friendship in the early twenties and collaborated many times artistically. Indeed, Masson was the dedicatee on Aragon's most famous Surrealist book Paysan de Paris (1926) and provided erotic illustrations for Le Con d'Irène (1928), Aragon's salacious novella (published under the pseudonym Albert de Routisie). Later, in 1977, Aragon wrote Masson a cantata (choral composition) which was accompanied by earlier drawings by the artist along with the caption: "In homage to André Masson and to mark here precisely what he was, what he is for me, throughout our lives: the great mental forest of our dreams".

materials - Pompidou Centre, Paris

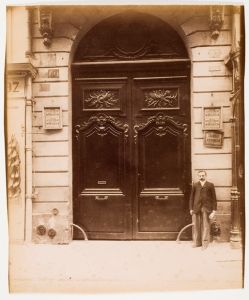

Place de l'Europe

This iconic image depicts a man skipping over a flooded area in the Place de L'Europe, just outside the Saint Lazare train station. The photograph illustrates Cartier-Besson's concept of the "decisive moment"- described by him as that "one moment at which the elements in motion are in balance" - in the way his camera freezes the exact moment the prancing man touches heels with his reflected image. Cartier-Bresson was inspired by the Surrealists, and we see that influence in the preoccupation with the idea of the uncanny doppelgänger (revealed in the man's reflection). The mystery of the man's flight is only strengthened by the "floating" ladder from which he appears to have sprung while the shadowy onlooker in the middle-distance merely completes the image's element of incongruity.

Beneath the chimney in the upper left of the frame, meanwhile, a circus poster shows a female dancer in a pose that copies that of the main subject. The superior lens quality of the Leica 35mm camera would lend the image a potential for fine picture detail such as this to emerge. It is also of some significance - for the idea of Street Photography as an art form in its own right - that Cartier-Bresson's figurative juxtaposition is set against a hazy background of Saint Lazare. These buildings had been painted previously by the likes of Monet and Manet which suggests that the famous photographer wanted to invite associations, not just with the Surrealists, but with the great pioneers of French modernism.

Gelatin silver print - Museum of Modern Art, New York

Painting, 23 May 1953

According to the Tate Museum, Pierre Soulages, "had [first] started using heavy brushstrokes of black paint against a light background in 1947. His style became more energetic and gestural throughout the 1950s. Soulages has said that for him abstraction is a way to explore his imagination and inner experience. 'I work, guided by inner impulse, a longing for certain forms, colours and materials,' he explained in 1950. '[It] is not until they are on the canvas that they tell me what I want'".

Soulages was a leader of Art Informel, and his was one of many overlapping approaches to abstraction in France in the mid-20th century. As the Guggenheim Museum describes, "though his rejection of bright color in favor of black set him in opposition to the major trends in French abstract painting of the time, Soulages was nevertheless a prominent exemplar of the Jeune École de Paris (Young School of Paris), an umbrella term for the gestural or post-Cubist abstraction produced by artists like [...] Soulages. Though superficially similar to the work of Abstract Expressionist artists such as [the American] Franz Kline, Soulages's paintings are very different in execution: in contrast to the gestural approach of his American counterparts, Soulages deliberately constructed his compositions to create a formal balance".

Oil on canvas - Tate Museum, London

Anthropometries of the Blue Period

Yves Klein emerged during the 1950s as the leading member of Nouveau Réalisme movement. He was a forerunner of Minimalist art, making his name for a series of monochrome paintings - blue and gold especially. He even registered his own pigment, "International Klein Blue" (IKB), with the Institut National de la Propriété Industrielle (IKB is not in fact patented, as is widely believed). With his monochrome paintings, Klein wanted to create works that were purely atmospheric, yet despite their uniformity of color, he experimented freely with methods of applying paint, including applying it to different surfaces using items such as rollers and sponges. But Klein was equally well known as a pioneer in Performance art.

For his controversial Anthropometries performances, Klein covered the walls and floor of his "stage" in white. His audience (and the artist himself) wore formal evening attire and the performance was accompanied by an ensemble who performed his self-penned Monotone Symphony (written in 1949), which was in fact a single note played for twenty minutes with pauses of twenty minutes of silence. But the true controversy arose through Klein's use of naked female models as "human paintbrushes" to apply the IKB paint ("In this way, I stayed clean. I no longer dirtied myself with color, not even the tips of my fingers", he stated, rather provocatively). Under Klein's direction, the models pressed their paint-covered bodies on the surfaces (some rolling or pulled across the floor) and on completion of the performance, Klein was left with a finished IKB artwork.

The works did, not surprisingly, raise the ire of some feminists (such as art critic Julia Steinmetz) who took exception to Klein's blatant exploitation of his models. However, one of Klein's models/participants, Elena Palumbo-Mosca, argued that Klein was her friend and that the Anthropometries performances were in fact collaborative: "This work is very beautiful", she said, "I like it very much. I know that it is the fruit of an extraordinary intellectual process on the part of Yves, and I contributed as best I could". The Anthropometries performances effectively overlapped painting and performance. In this aspect it fitted with the Neo-Dada idea that sought to fuse different mediums. However, Klein distanced himself from Nouveau Réalisme movement because of its associations with the Dadaists. Indeed, Klein called his work "réalisme d'aujourd'hui" ("today's realism").

Oil on paper

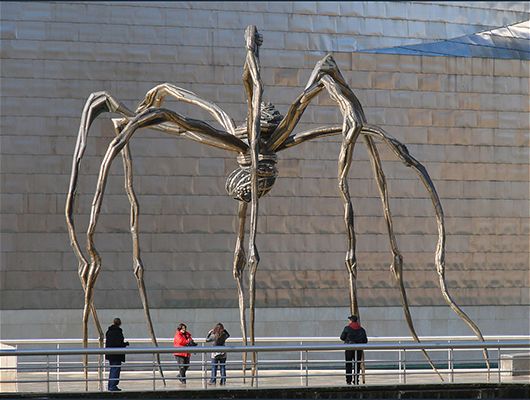

Maman

Louise Bourgeois is as one of the most important French artists of the second half of the twentieth century. Her oeuvre, which overlaps different genres and materials, is driven primarily by her personal life experiences; all her art, she said, was "the re-experience of a trauma" and her only "guarantee of sanity". Exploring themes such as fear, anger and loneliness, Bourgeois has switched between many mediums, including painting, printmaking, drawing and Performance art, and worked across abstraction and figuration. She fell in and out of fashion until she was given a retrospective at New York's Museum of Modern Art in 1983. Galvanized by the success of that exhibition, Bourgeois went on to produce her most iconic works, including disturbing room-size Cells and her colossal Spider sculptures, for which she is perhaps best-known today.

Maman (Mummy) is a 30-foot tall; 33-foot wide, bronze, stainless steel and marble sculpture depicting a spider. With its long spindly legs, Maman includes a sac containing 32 marble eggs. It is one of the largest sculptures in the world and, as with most of the works in her oeuvre, it addresses issues relating to Bourgeois's complicated childhood relationship with her parents (including her father's flagrant infidelity). Maman, as the title tells us, is a clear nod towards the artist's own mother who here is represented as the fearsome spider who protects her beloved eggs/children in an abdomen and thorax made of impenetrable ribbed bronze. Maman's intimidating height and scale connote the creature's power and potency, yet Bourgeois raises her up on such slender legs she expresses a palpable feeling of vulnerability too. As author Silka P summed up, "Bourgeois's personal visual language referenced mythological and archetypal imagery [and by featuring] objects such as spiders, spirals, cages, and medical tools, her work symbolizes the feminine psyche. For this French sculptor, art making was a therapeutic or cathartic process".

Bronze, stainless steel, marble - Guggenheim Museum Bilbao, Bilbao, Spain

After ALife Ahead

Pierre Huyghe came to prominence in the 1990s when he became known for his "postproduction" technique which involved the recycling of images from mass media (for his 1999 video film, The Third Memory, for instance, he restaged the true-life bank robbery featured in the 1975 movie Dog Day Afternoon). He addressed themes of leisure and adventure through his films, performances, and public events, but more recently he has grabbed the attention of the art world for his ambitious installations. These typically involve living insects, plants, animals, and even human beings. He describes these works as "laboratories" where he and his audience can critically explore the ways in which human beings interact with their natural world, and through that process, create what he has calls "new realities".

For After Alife Ahead, Huyghe took over a large former ice-skating rink. As author Emily McDermott explains, Huyghe placed "[cancer cells], bees, peacocks, and algae inside the excavated hangar-like structure, transforming into a living organism and animating it via an augmented reality app". She describes how the ice rink's "concrete floor is broken apart, with steps and a dirt ramp descending into the muddy, dugout ground" while sections of the ceiling cyclically open and close to expose the installation to the natural elements (light, wind, rain). The installation also features an aquarium and "many smaller, yet equally significant components at play within the space".

Here, as in other installations, Huyghe is contemplating the place of human beings in the larger natural world. McDermott writes that for Huyghe, "the project's complexity isn't intended to confuse viewers but instead to make them question where its processes (and thereby wider processes within our lives) begin and end". In conversation with curator Hans Ulrich Obrist, Huyghe said of his installations: "I don't want to exhibit something to someone, but rather the reverse: to exhibit someone to something". He added that "When what is made is not necessarily due to the artist as the only operator [and] that instead it's an ensemble of intelligences, of entities biotic or abiotic, beyond human reach [it is] at that moment perhaps the ritual of the exhibition can self-present".

Installation - Skulpture Projekte, Münster, Germany

Early French Art

Beginnings

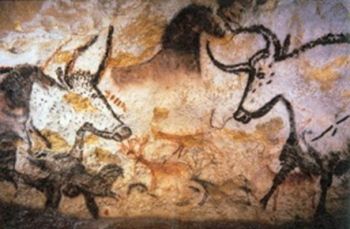

Although there was yet to be any concept of a nation state, the history of French art dates back to Cave art with the wall drawings and carved relief sculptures found in several of its caves. Two of the most well-known are the Chauvet-Pont-d'Arc Cave (or Chauvet cave) in France's Ardèche Valley, and the Lascaux cave in the Dordogne region. The Lascaux cave was discovered in 1940 while France was under Nazi occupation. A group of young boys were trespassing on the private property of the Count of La Rochefoucauld when they squeezed their way through a partially concealed opening and entered a cave which is today known as the Hall of Bulls. They had discovered what was the most finely decorated cave in Europe.

Dating back to 30,000 BC, and discovered in December 1994 by three cave explorers, the Chauvet cave is home to the oldest of the French cave paintings. Some 400 meters long with two major parts, the walls are decorated with images of horses, lions and rhinoceroses (animals that were rarely hunted and therefore likely had animistic/spiritual properties), and several human handprints.

The Venus of Laussel (or Woman Holding a Bison Horn) is one of the earliest examples of a carved relief sculpture in art history. Found in the Laussel cave in the Dordogne region, the work, which dates from around 25,000 BC, depicts a woman holding a bison horn in her raised right hand. While the meaning of the work cannot be confirmed, the exaggerated breasts and hips of the woman, coupled with the thirteen marks on the horn the figure holds (which some historians believe represent a woman's menstrual cycle), led many to believe the work's meaning is probably linked to fertility.

The Romanesque Period

The first French city, Marseille, began life as a Greek colony (Massalia) in 600 BC. By 222 BC, the Roman Republic ruled the expansive western European region of Gallia (Cisalpine Gaul). The legacy of Roman rule can be found in the wonderfully preserved (due largely to the fine weather conditions in Southern France) limestone Arc de triomphe d'Orange in the Provence town of Orange. The arc, dedicated to the second emperor of Rome, Tiberius Caesar Augustus, is made up of panels depicting land and sea battles and various war trophies. Gaul remained under the rule of the Roman Empire until the fourth century when the Franks - from which France takes its name - took power. Charles the Great (Charlemagne) united the Gaul regions and was named the Holy Roman Emperor of French and German monarchies in 768 (France would remain a monarchy for a further thousand years).

The years between the fifth and the fifteenth century - the Medieval or Middle Ages - mark the beginnings of a distinctly French art. According to author Valentin Grivet, "if cave paintings and some ancient works are not counted [then] the Middle Ages were the first great epoch of French painting". Indeed, during the Middle Ages two key movements, the Romanesque and Gothic periods, put down roots in France and some of the greatest examples of medieval art and architecture were created in these styles. The first of the French movements was the Romanesque period which dated from the late tenth to the thirteenth century (when it was overtaken by the Gothic style). Vast monasteries, pilgrimage churches, frescoes and bejewelled memorials were produced in the Romanesque style. The architectural style was characterized by rounded stone arches (that looked back to early Roman architecture) and simple cross layout floor plans.

While Romanesque churches and cathedrals were somewhat nondescript on the exterior, the interiors brought the buildings to life with walls and ceilings covered with frescoes, and ossuaries celebrating Christian narratives. Relief carvings and sculptures often displayed Christian narratives carved into tympanums. One of the best-known examples was produced by the French artist known as Gislebertus who made the Romanesque relief depicting the Last Judgment of Christ for the tympanum of the Cathedral of Saint Lazare in Autun, in 1130. Painted icons and ornately decorated reliquaries or holders for holy relics were given prominence of place in the Romanesque churches which served as key attractions for those making pilgrimages to churches scattered throughout the country.

The Gothic Period

The French Gothic style covered the period between the twelfth and fifteenth centuries. Architecturally, church design became more ambitious with builders aiming to attain greater height. Stained glass became popular too, with church windows as one more means by which artisans could illustrate Christian narratives. Pointed arches and rib vaults helped accommodate the new building heights with slanting - or "flying" - buttresses introduced to support the building's increased height and weight. Paris's iconic Notre-Dame Cathedral is generally agreed to be the definitive example of French Gothic architecture.

The Gothic church's move towards more ornate designs can be seen in the decorative rosette windows and pointed arches, and in the abundance of religious themed art that adorned the interior, and on the exterior walls, of the buildings. Gothic art was more realistic than earlier Christian art and was especially true of sculpture which anticipated the emergence of the Renaissance movement. According to author Silka P, French sculptors of the Gothic period "were crucial for the experimentation with the traditional art materials, such as clay, marble, and bronze [and were] responsible for the most thought-provoking and revolutionary ideas regarding three-dimensional creativity".

While representations of Mary and the Christ child were popular throughout the Middle Ages, in many early images Christ is represented less as an infant and more like an adult of reduced size. In the Virgin of Paris in the Notre Dame cathedral, Mary and the Christ child are more natural (or childlike in Christ's case) thus representing a Gothic style that has moved away from the flat and simplified forms of religious iconography of the Late Antiquity and the Byzantine periods. This feature is most notable in the natural way in which Mary's body curves to support the weight of the child she rests on her hip. This natural parental posture became commonplace during the late-Gothic period. Book arts was also a common feature of Gothic art. Illuminated manuscripts and small books of prayers (books of hours) were commissioned by wealthy patrons for private devotion. While many of the books were created by anonymous artisans, some individuals, such as Jean Fouquet, Master Honoré, and Jean Pucelle, began to gain recognition under the collective title: School of Paris.

French Art 1450-1750

The Renaissance in France

While the Renaissance period had its beginning in Italy, the movement, with its emphasis on humanism and a mathematical approach to perspective, quickly spread across western and northern Europe. According to author Valentin Grivet, "The French Renaissance reached its peak between the last years of the 15th century and the end of the following century. Its development can be divided into different phases, starting with [early works] whose aesthetics still combined Gothic elements with new design principles, and for example, produced the painter Jean Fouquet, up to the last manifestations of Mannerism towards the end of the 16th century".

In addition to religious works, portraiture became an increasingly popular theme in Renaissance painting. Of this style, perhaps the area in which France best excelled was in works capturing royalty and military leaders. The great kings and queens of France, and sometimes even their mistresses, were subjects for artists, while the Royal courts could boast of having some of the greatest painters of their age as members.

The greatest French Renaissance master in this genre was the court painter Jean Clouet who is best known for his portraits of King François I (reigned 1515-47). François is credited with doing more than any other individual to promote Renaissance art and architecture in France. François was a progressive, cultured, monarch who invited Leonardo da Vinci to come and work freely in France. Leonardo accepted the King's invitation and lived out the last three years of his life (1516-19) in a relatively small palace (the King's childhood home) in Amboise in the Loire Valley. Leonardo brought with him a large cache of paintings and drawings, most of which stayed in France (and are now housed in Le Louvre as part of the world's largest single collection of Leonardo's art).

Leonardo and King François formed a close friendship, and although he died shortly before construction began in earnest, it is thought that the great Renaissance master designed the famous double-helix staircase (two concentric spirals wind separately around a central column, allowing guests to pass without meeting while still being able to see one another through windows placed in a central column) of the castle, Chateau de Chambord. The Renaissance Chateau, commissioned by François, and one of the first in France to revive the ancient Greek and Classical Roman architectural styles, was designed by the Italian Domenico da Cortona who created the wooden model which builders then constructed in stone. However, such was the duration of the interrupted construction period (some 28 years), French Renaissance architects Jacques Sourdeau, Pierre Neveu, Denis Sourdeau, and Francois de Pontbriant (the project's overseer) are now credited as key contributors to the Chateau's final design.

The Academy

The painter, designer and art school director Charles Le Brun played the leading role in establishing the Académie Royale de Peinture et de Sculpture (Royal Academy of Painting and Sculpture), under the patronage of King Louis XIV, in 1648. Le Brun was part of a group of artists who felt constrained by the medieval Gothic and Baroque styles, which were still dominant in France.

By 1661 the French Royal Academy began promoting a classical - or royal - style, devoted to the glorification of Louis XIV, and this model influenced the development of other academies throughout Europe (including British and Danish Academies). Academies were vital in fostering national schools of painting and sculpture and remained pinnacles of aspiration for most French artists long into the nineteenth century. Appointed as the French Academy's director in 1663, Le Brun modelled the French system on the older Italian Academies, opening an art school, enlisting noted patrons, and upholding strict classical standards. At the same time, the French Academy made its own contributions, expanding its role to include an annual Salon where members exhibited their work; a division of the French Academy in Rome; the Prix de Rome award which granted a three-year scholarship for a student to study in Rome; and the establishment of a "Hierarchy of the Genres" which ranked "complex" history painting and sculpture over, say, landscapeture and portraiture.

Poussinistes versus Rubenistes

For the Académie Royale, the conflict between colorito and disegno took on new energy between the "Poussinistes" - those who preferred the classical works of Nicolas Poussin (who spent the majority of his career in Rome) - and the "Rubenistes" - those who favored the more sensuous works of Flemish painter Peter Paul Rubens. At a 1672 Academy conference entitled Sentiment on the discourse on the merit of colour, Le Brun argued "drawing imitates everything real, whereas colour only represents the accidental". Color was considered an aesthetic embellishment, or, as Le Brun put it, "color depends entirely on matter, therefore it is less noble than drawing, which depends only on the mind".

The Poussinistes would win the debate, establishing Poussin as the central figure to the Academy's teachings. Indeed, many Academians cited Poussin as Raphael's rightful heir. As art historian Michael Paul Driskel put it, "by interpreting Poussin as the 'French Raphael,' French art theorists in and around the Academy heightened Poussin's prestige and strengthened his pedigree as the father of the French classical tradition [...] in the hope of creating their own version of the beau idéal [the highest possible standard of excellence]".

Baroque Art

![<i>Portrait of Louis XIV</i> (1700-01). Historian Juyeon Kim states, “in Hyacinthe Rigaud's most famous portrait, Louis XIV [aka. the “Sun God”] shows the majestic power of an absolute monarch. He is wearing his coronation robe embroidered with the royal <i>fleur de lys</i> along with some key elements of Baroque [fashion] style such as the cravat, red heels, and the wig”.](/images20/photo/photo_french_art_10.jpg)

Perhaps the defining movement of the seventeenth century was the Baroque movement. Many French artists and designers embraced the dramatic and excessively decorative elements of the Baroque style. It was a movement designed to overwhelm the emotions and is often thought to represent the good taste (or excesses, depending on one's point of view) of the French aristocracy and the aspiring middle classes (or petite bourgeoise). One of the leaders of the Baroque style was the portrait painter Hyacinthe Rigaud. He was well known for his portraits of King Louis IV and his heirs. His sitters were theatrically posed; usually seated or standing against richly decorated backgrounds and bedecked in extravagant regal costumes.

Portrait busts, which would help immortalize their subjects, were also popular within Baroque art. These were mostly royal and military commissions, such as the bust commissioned by King Louis XIV created by Antoine Coysevox, in 1686. Busts like these adorned the halls of royal residences, including the spectacular Royal Palace at Versailles, France's lasting monument to the Baroque and Rococo age.

While it is true that much of Europe was fascinated by the dramatic, almost theatrical, representations of grand subjects and their residencies, in the hands of many French artists, the Baroque style took on a more austere tone. Indeed, the theatricality of the Baroque style was seen by French artists as somewhat immoderate and was offset with a more sober consideration of composition that accommodated more considered classical ideals (hence the sometimes-used title, "Baroque Classicism").

Rococo: The French Art of Leisure

Following the death of King Louis XIV in 1715, the French aristocracy moved from the court of Versailles back to their Parisian homes. They turned away from the excesses of the Palace's Baroque style and filled their mansions with more genteel designs and furnishings. Pastel tones and smooth rounded contours were the order of the day, and paintings typically depicted frivolous love scenes, views of nature, and youthful amorous encounters. As art historian Erica Trapasso summarized, "Instead of surrounding themselves with precious metals and rich colors, the French aristocracy now lived in intimate interiors made with stucco adornments, boiserie, and mirrored glass. This new style is characterized by its asymmetry, graceful curves, elegance, and the delightful new paintings of daily life and courtly love, which decorated the walls within these spaces".

Amongst the greatest exponents of the Rococo style was the academy painter Jean-Antoine Watteau. He first gained recognition as a painter of scenes featuring commedia dell'arte (paintings based on popular Italian theater characters) but is better known for inventing a type of painting known as Fête Galante (or "outdoor courtship entertainments"). These were typically small cabinet paintings that showed romantic love scenes set in a rich landscape setting. Grivet, placed François Boucher in the same class as Watteau, noting that Boucher's "themes of pleasure and sensuality" were sometimes tinged "with a touch of eroticism or licentiousness" and adding that it was Boucher who emerged as the acknowledged "master of velvet-white female nudes".

Rococo paintings were typically commissioned by wealthy patrons, often of noble or royal lineage. Indeed, Jean-Honoré Fragonard's Progress of Love (1770-73) four-panel series was created for the private rooms of King Louis XV's mistress, Madame Du Barry. But Rococo paintings did not have broad appeal, especially amongst ordinary French people, many of whom were simply struggling to endure day-to-day life. As the art historian Erica Trapasso writes, "Though educated thought was cultivated throughout the 18th century, a new kind of intellectual exchange began to develop, which became known as the Enlightenment. Out of this new cultural movement, ideas about art changed, and Rococo ideals of frivolity and elegant eroticism became less and less relevant. Art critics like [Denis] Diderot sought for a 'nobler art,' and enlightened philosophers like Voltaire criticized its triviality. While some Rococo artists continued to paint in their own provocative style, others developed a new kind of art, known as Neoclassicism, which appealed to the art critics of the time".

French Art 1750-1850

Neoclassicism

By the middle of the eighteenth century, Enlightenment thinkers were calling for an art that better reflected the dawning of a new age and they found their inspiration it in the art of Roman antiquity. The art historian Dr. Jeanne S. M. Willette describes that the roots of French Neoclassicism could be located in the middle of the century with the archaeological discovery of the Italian resort towns of Herculaneum and Pompeii (which had been buried in the eruption of Mount Vesuvius in 79AD). As she writes, "Frozen in time, magnificent villas were unearthed, revealing extraordinary murals painted by provincial artists [...] Suddenly the linear and simple approach to drawing and the cleanly painted areas of colors provided a new way to make art to a young generation of artists who wanted to make their marks in the Academy and upon new patrons". She adds that the "affinity to the simple compositions and strong lines of Poussin" had made it easy to "assimilate the paintings of Pompeii for artists who were interested in being radical", even though it would take some "four decades to come to fruition".

French Neoclassicism can be divided into two phases. Willette describes how the first flowerings were evident in "the frozen eroticism of Joseph-Marie Vien". He, with the London based Swiss artist (and co-founder of the British Royal Academy) Angelica Kauffman, painted women bedecked in Greco-Roman gowns and engaged in everyday activities. It was through such pieces that Vien introduced the Neoclassical style to the French art world through the Salon Carré in 1763. Although the works of Vien were about everyday domestic life, towards the end of the century, Neoclassicism would enter a second phase that adopted the more ethical and serious tenets of history painting. Willette observes that in the second phase "heroic men would take the center stage as active and noble subjects. Monumentality and sober and serious colors, strong shadows and theatrical settings filled with brave men engaged in virtuous enterprises became the preferred style at the end of the Eighteenth Century".

Jacques-Louis David, and his one-time student, Jean-Auguste-Dominique Ingres, emerged as perhaps the leading figure in second-phase French Neoclassicism. He developed something of a universal style (in that its righteous principles appealed to nobility and revolutionaries alike). However, Neoclassical art was dependent on the patronage of the monied classes and the shift to grander history paintings was an undisguised attempt to elevate Neoclassicism to the status of the "highest art". Willette makes the further point that while "It is often assumed that suddenly Rococo art disappeared as soon as Neo-Classicism hove into view" in fact "the Rococo style never faded away and was beloved to the extent that during the Second Empire [1852-70], it - not Neo-Classicism - was seen as the true national style of France".

The Romantic Period

The art historian E H Gombrich wrote: "The leading conservative painter in the first half of the nineteenth century was Jean-Auguste-Dominique Ingres. He had been a pupil and follower of David, and like him admired the heroic art of classical antiquity. In his teaching he insisted on the discipline of absolute precision in the life-class and despised improvisation and messiness [...] It is easy to understand why many artists envied Ingres his technical assurance and respected his authority even when they disagreed with his views. But it is also easy to understand why his more passionate contemporaries found such smooth perfection unbearable. The rallying call for his opponents was the art of Eugène Delacroix [...] He had no patience with all the talk about Greeks and Romans, with the insistence on correct drawing, and the constant imitation of classical statues. He believed that, in painting, color was much more important than draughtsmanship, and imagination than knowledge".

There was in fact a period of transition between Neoclassicism and Romanticism bridged by Anne Louis Girodet (a former student of David). Girodet's dramatic subject matter, unnatural coloring, and his (sic) highly emotional re-imaginings of classically themed material went against the reason and order of the Enlightenment artists and saw him pointing towards the more expressive Romantic movement. Romanticism did not restrict itself to a specific genre. It is true that internationally the movement is concerned with art that captures the power and majesty of nature (known to art historians as the aesthetic of "the Sublime"). In France, however, artists such as Delacroix and Théodore Géricault were working in the Romantic idiom as a way of dramatizing topical themes of human equality and social justice.

![Théodore Géricault, <i>The Raft of the Medusa</i> (1818-19). According to author Edward Lucie-Smith “the motive force [behind Romanticism] is not hero-worship [or a tribute to classical antiquity] but indignant compassion”.](/images20/photo/photo_french_art_14.jpg)

Géricault's epic painting, The Raft of the Medusa, for example, features a disturbing grouping of figures some dead, some struggling for life, in a tangled mass positioned on a makeshift raft. The painting is a dramatic interpretation of real events, beginning on July 2, 1816, when a French navy frigate carrying individuals to establish a new colony sank off the West African coast. The appointed governor of the colony, with the top-ranking officers in the party, left on the ship's six lifeboats leaving the remaining 147 passengers to crowd onto rafts. When the raft proved too cumbersome, in what was interpreted as an act of extreme cowardice, the ship's captain cut the ropes to the raft leaving the passengers to the mercy of nature. When rescued thirteen days later by a passing British ship, only fifteen men were alive with five of those dying before they were able to reach the safety of land. Once the story was reported in the press, it became a national scandal, and a strong indictment of the priorities of the current French government.

In the Romantic period, domestic themes coexisted with scenes of exotic overseas travel. A focus on the naked female form was shown in ways that seemed both alluring and forbidden when executed through the Romantic sub-genre of Orientalism. Author Alexandra Jopp states, "the new Romantic concept of beauty included exotica - something unique, uncommon, unexplored, sensual and erotic. This cult of the exotic explains the fascination of French and British painters with the Near and Far East, Northern Africa and the Mediterranean region, particularly as reflected in the picturesque Orientalist paintings of Jean-Léon Gérôme, Eugène Delacroix, and Jean Auguste Dominique Ingres. For these painters and others in the Romantic era, Orientalism would become an essential feature of their work".

Realism

The concept of realism in art has a long and complex history that dates all the way back to Greek antiquity. However, Realism became a self-defined movement in French art (and literature) that lasted roughly between the 1840s to the end of the century. The Realist doctrine insisted on an honest, unvarnished, depiction of the natural world - with ordinary working-class subjects represented (if at all) without embellishment or fanfare. Realism rejected Academy standards, especially Neoclassicism and Romanticism, and portrayed the French landscape and elements of society that had often been ignored by the "official" art establishment. The key figure within the Realist painterly tradition was Gustave Courbet although the landscapists Jean-Baptiste-Camille Corot and Jean-François Millet, and the caricaturist, Honoré Daumier were exploring the similar ideas and themes.

Ross Finocchio of the Metropolitan Museum of Art, writes, that despite precedents dating back to the beginnings of the century, French Realism came into its own "in the aftermath of the Revolution of 1848 that overturned the monarchy of Louis-Philippe and developed during the period of the Second Empire under Napoleon III". It accorded with Courbet's 1861 statement that "painting is an essentially concrete art and can only consist in the representation of real and existing things" and was mirrored "in the naturalist literature of Émile Zola, Honoré de Balzac, and Gustave Flaubert" and that the "elevation of the working class into the realms of high art and literature coincided with Pierre Proudhon's socialist philosophies and Karl Marx's Communist Manifesto, published in 1848, which urged a proletarian uprising".

Corot was a landscape painter that history now treats as an intermediary figure in the development of Realism and the birth of modernism. Although he himself was classically trained, his paintings mark the first moves away from the historical and mythical preoccupations of his peers and predecessors in the Academy. From the late 1820s, he made several excursions to the Fontainebleau Forest where he became friends with painters from The Barbizon School. Through such association, Corot's painting adopted an increasingly naturalistic, more spontaneous, style that was carried forward by the likes of Millet and Courbet (and, later still, by the Impressionists).

Reacting against the idealized historical landscapes that provided the backdrops for mythical and religious narratives. The Barbizon School, named after the village in the north-central region of France near which it was situated, were committed to a more faithful representation of nature and peasant life. These artists baulked at the overindulgences of Romanticism and represented the natural world without artistic embellishment. However, while the Barbizons focused predominantly on the landscape, some works, such as those produced by the deeply religious Millet, were apt to portray peasant labourers as laudable and noble figures. The working-class man and woman would also become established protagonists in Impressionist paintings.

A friend Corot's, the Parisian caricaturist, Honoré Daumier, produced finely detailed satirical lithographs that were in many ways the urban companion to Corot. Aimed at exposing the divisions and inequalities within French society, Daumier was a committed socialist, and he, like Millet, made heroes of the working classes and villains of establishment figures. He produced works for several journals, including La Caricature and Le Charivari, that lampooned the state and the bourgeois classes (he was even imprisoned).

There is little dispute that Gustave Courbet was to emerge as the central figure within the Realist movement. He was ardent in his opposition to all forms of aesthetic embellishment and was committed to representing the everyday without even glorifying the ordinary worker. By removing any sentimentality from art (a charge that could be levelled at Millet) Courbet was pursuing a route to a truer democratic art. In the 1850-51 Salon, he exhibited Burial at Ornans (1849) and the Stone Breakers (1849). Monumental in scale, and crude (by Academy standards) in execution, the paintings shocked both the art world, and the public, who were not accustomed to, nor ready for, such blunt representations of peasant life.