Summary of Old Masters

The term Old Master is used to identify an eminent European artist from the approximate period 1300 to 1800 and includes artists from the Early Renaissance through to the Romantic movement. The expression can also be used to refer to the artwork produced by one of these artists, most commonly oil paintings or frescos, but also drawings and prints. The term was used widely from the 18th century and this can be placed in the context of the rise of the European art academies and galleries at this period, who, through collection and education policies, codified what was seen as 'good' historical art and consequently created the modern idea of the Old Master. As with any concept that encompasses such a broad range of art and artists, there is some significant debate as to the exact criteria that defines an Old Master, particularly regarding the date range included and the necessary skill level or renown of the artist.

Key Ideas & Accomplishments

- Originally a master artist or craftsman was an individual who had been fully trained in the guild system, and had progressed to working independently, often taking on pupils of their own. This differs from the modern iteration of the term in which artists worked outside of the guilds or in other, more modern, contexts (for example, Paul Cézanne) can also be classed as Old Masters (or sometimes refered to as "Modern Masters"). As in its previous usage, however, the term continues to denote a level of quality.

- The most famous works by Old Masters are characterized by innovation in technique and style as well as a drive to create believable figures and landscapes through the realistic representation of perspective and proportion.

- From the 18th century, copying the works of Old Masters became the baseline for art education and students were expected to become proficient in this before being allowed to draw from life. This consolidated the importance of the Old Masters and placed them in a position of reverence.

The Important Artists and Works of Old Masters

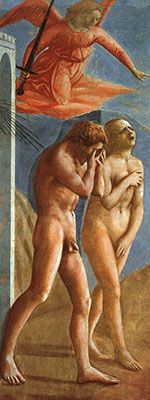

Expulsion from the Garden of Eden

This early Old Master work, part of Masaccio's fresco cycle in the Brancacci Chapel, depicts a nude Adam and Eve, their body language and facial expressions conveying shame and anguish, as they are driven from the garden of Eden. From the arch behind them black lines depict the voice of God while above the arch an angel, dressed in red and carrying a black sword, energetically drives them forward. Both the lines depicting the voice of God and the sword are made of silver, though it has tarnished over time. The influence of classical sculpture is evident in the proportions of both figures, while Eve's arms covering her breasts and pubic area specifically evokes the Venus Pudica pose, which was widely used by later artists. In his depiction of Adam, Masaccio was also influenced by Donatello's Crucifix (1412-13) in the Santa Croce church, known for its realistic depiction.

Painting the first nudes since the Roman era, Masaccio's innovations, realistic figuration and linear perspective, created a new aesthetic. As 16th century painter, Giorgio Vasari wrote, Masaccio brought "into light the modern style that has been followed ever since by all artists" Direct influences can be seen in the work of Fra Filippo Lippi, Sandro Botticelli, da Vinci (who called Masaccio's figures "perfect"), and Michelangelo as well as later names including John Ruskin, Joshua Reynolds, and the sculptor Henry Moore. As contemporary art historian Keith Christiansen noted, "the methods Masaccio employed on the walls of the Brancacci Chapel did indeed become the basis of art training throughout Europe".

Fresco - Church of Santa Maria Novella, Florence, Italy

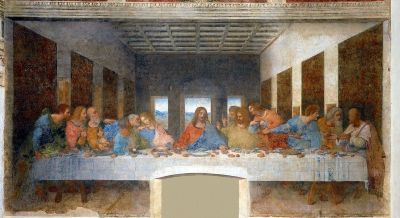

Mona Lisa (La Giaconda)

Probably the most famous and most recognizable of paintings, this Renaissance portrait depicts a woman whose mysterious smile and identity has fascinated scholars and viewers for centuries. In its techniques and its treatment of the subject matter, Leonardo's work was radically innovative. Previously female portraits, usually commissioned by male family members, depicted the sitter in profile and emphasized her social status, and suitability as a wife, by attention to her finery and jewelry. Da Vinci's pioneering use of sfumato, the application of multiple thin layers of glaze, creates the work's soft tonal transitions and gradations between light and shadow. This, along with his knowledge of anatomy and mastery of perspective, creates the realism of the piece. As Giorgio Vasari wrote, "As art may imitate nature, she does not appear to be painted, but truly of flesh and blood. On looking closely at the pit of her throat, one could swear that the pulses were beating."

Landscape becomes a focus of the work, rather than a mere backdrop, as its features, rendered in aerial perspective, resemble realistic landscape forms but, taken altogether, evoke an imagined world. As Louvre curator, Jean-Pierre Cuzin wrote, "The background may be a representation of the universe, with mountains, plains and rivers. Or possibly it is both reality and the world of dream. One could suppose that the landscape doesn't exist, that it is the young woman's own dream world."

Though most scholars believe he began painting the work in Florence around 1500, da Vinci subsequently took the work with him to France and worked on it until his death. As Cuzin wrote "The entire history of portraiture afterwards depends on the Mona Lisa. If you look at all the other portraits - not only of the Italian Renaissance, but also of the seventeenth to nineteenth centuries - if you look at Picasso, at everyone you want to name, all of them were inspired by this painting. Thus it is sort of the root, almost, of occidental portrait painting." Da Vinci's techniques of chiaroscuro, sfumato, linear perspective, and aerial perspective, and his use of composition, became foundational to subsequent artists. Due to his equally celebrated scientific discoveries, inventions, and observations (recorded in his notebooks) he was viewed as the exemplary Renaissance man, a master in all that he attempted.

Oil on panel - Musée du Louvre, Paris

The Creation of Adam

This iconic work, part of the famous fresco cycle Michelangelo painted on the Sistine Chapel, depicts the moment when God, shown in a cloud of angels and cherubim on the right, conveys the spark of life to Adam, nude and reclining on the left. Influenced by classical Greek and Roman sculptures, Michelangelo's figures are both idealized and sculptural, elevating the nude, which in previous Christian art had been employed only to depict Adam and Eve, in shame, as they were driven out of paradise.

Here, he creates a powerful image of male beauty, which influenced both artistic treatments and cultural beliefs, reflected in the 20th century by Pope John Paul II's comment, "The Sistine Chapel is precisely - if one may say so - the sanctuary of the theology of the human body."

Pope Julius II commissioned the painting of the ceiling of the Sistine Chapel in 1507. The result was immediately hailed as an age-defining masterpiece and was an early exemplar of history painting. Michelangelo was also noted for his innovative compositions including the use of foreshortening, a vibrant color palette, and dynamic movement. In the 17th century the emerging art academies defined history painting as one of the highest forms of art. Copying Old Master works in the genre was emphasized in the educational process and many artists travelled to Rome to study the work. Michelangelo's depiction of the human form greatly influenced Titian, Bernini, Rubens, Rodin and Paul Cézanne amongst others.

Fresco - Vatican City

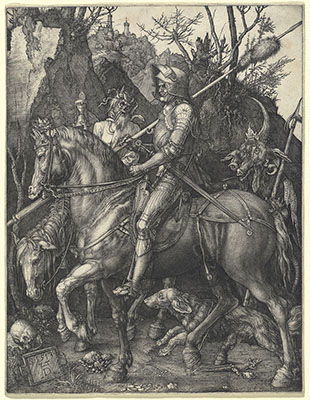

Knight, Death, and the Devil

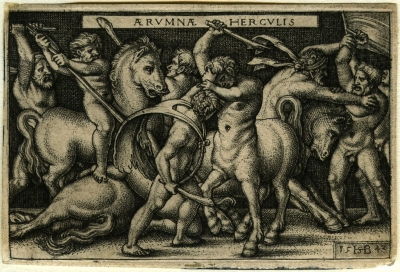

This large print, along with Saint Jerome in His Study (1514) and Melacholia I (1514), is one of Dürer's Meisterstiche, or master engravings. An equestrian knight, dressed in armor, and carrying a lance, its tip wrapped in a foxtail, fills the picture, as he rides resolutely through a craggy and desolate landscape. He looks sternly forward, not looking at Death, on a horse to his right, who exhorts him or the goat-headed Devil who follows behind him. His faithful dog runs alongside. The work is profoundly allegorical, from the skull on the ground in front of the horse to the hourglass that Death holds, and is perhaps based upon the Renaissance Humanist Erasmus's Instructions for the Christian Soldier (1504), which said, "In order that you may not be deterred from the path of virtue because it seems rough and dreary ... and because you must constantly fight three unfair enemies - the flesh, the devil, and the world... Look not behind thee." Dürer's own title for the work was simply the Reuter (Rider), reflecting his emphasis on the knight as a heroic figure.

Durer devoted his life to producing proportionally accurate depictions of people and animals and is thought to have been influenced by his studies of the equestrian statues of the Italian Old Masters, including Donatello's Gattamelata (1453) or Leonardo's 1490 designs for an equestrian statue that was never completed. Giorgio Vasari said that Durer's master engravings were "of such excellence that nothing finer can be achieved". Durer was extremely innovative in his printmaking, expanding its tonal and narrative range, elevating it to an art form in its own right and influencing subsequent artists, notably the Little Masters. Additionally, his prints were reproduced and distributed throughout Europe, making them one of the first examples of mass-produced art. As a result, artists including Raphael, Titian, and Parmigianino began to collaborate with printmakers to promote and distribute their work.

Engraving - The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, New York

The Hunters in the Snow

This landscape shows three hunters, along with their hunting dogs, as they trudge through the snow on a hill overlooking a small village, where on the frozen river and large ponds villagers are skating. Presenting a compelling view of rural life, the work employs a masterly sense of composition, as the diagonal created by the hunters' dark outlined figures is echoed in the diagonal of black tree trunks that descend down the hill. This line can be seen to continue across the white strip of land between the ponds to the rugged peaks in the distance. This work is one in a series that Breughel painted depicting the seasons, but as art historian Jacob Wisse noted, "Though rooted in the legacy of calendar scenes, Brueghel's emphasis is not on the labors that mark each season but on the atmosphere and transformation of the landscape itself. These panoramic compositions suggest an insightful and universal vision of the world."

Breughel's works informed the development of landscape and also genre art, as his scenes depicting ordinary life were studied for his use of linear perspective, bold outlines, and repeating triangular shapes. He influenced the artists of the Northern European Renaissance and of the Dutch Golden Age, as well as later artists such as Camille Pissarro and Vincent Van Gogh. As contemporary art critic Jonathan Jones wrote, "Scenes such as The Hunters in the Snow seem to sum up the very nature of life on earth in their geographical sweep and anthropological scope. Like Shakespeare, he can capture the theatre of life."

Oil on wood - The Kunsthistorisches Museum, Vienna, Austria

The Supper at Emmaus

This work depicts the moment when the resurrected Christ reveals his identity to two of his disciples at Emmaus. Placed as if in a small, candlelit tavern, the scene emphasizes the moment of revelation. Christ, his face and body illuminated, is depicted gesturing to the viewer, while the disciples react physically, one with arms extended in astonishment and the other as if about to rise from his chair. Although he didn't invent the technique, Caravaggio mastered and popularized chiaroscuro, making it a dominant stylistic element in his paintings and using it to increase the drama and movement of his work. He also focused on creating realistic figures, rather than idealizing them, a technique that made him controversial in some religious circles.

Groups of artists, such as the Utrecht Caravaggisti, imitated Caravaggio's use of chiaroscuro and his emphasis on dramatic moments and he also influenced Rubens, Vermeer, Rembrandt, and Velázquez. As art historian Bernard Berenson wrote, "With the exception of Michelangelo, no other Italian painter exercised so much influence". The modern art critic Roberto Longhi noted, "Ribera, Vermeer, La Tour and Rembrandt could never have existed without him. And the art of Delacroix, Courbet and Manet would have been utterly different."

Oil on canvas - The National Gallery, London

Las Meninas

This intricate composition depicts the Infanta Margaret Theresa attended by her entourage, including two maids of honor, a chaperone, a bodyguard, two dwarfs, and a mastiff. To the left, Velazquez portrays himself painting onto a large canvas and in the background a mirror reflects the King and Queen who appear to be standing in the same position as the viewer. Alternatively, it has been posited that the reflection is of the painting on which Velazquez works. Nominally, a portrait of the Infanta, this work is a complex exploration of the phenomenon of visual perception which raises questions about reality and illusion in art.

The Baroque artist Luca Giordano described the work as representing the "theology of painting," whilst in 1827 the painter, Thomas Lawrence said it evoked "the true philosophy of the art". The work has continued to preoccupy and provoke contemporary thought. The noted philosopher Michael Foucault wrote, "We are looking at a picture in which the painter is in turn looking out at us. A mere confrontation, eyes catching one another's glance, direct looks superimposing themselves upon one another as they cross. And yet this slender line of reciprocal visibility embraces a whole complex network of uncertainties, exchanges, and feints." Foucault saw the work as presaging a new way of thought, occupying a point between the classical and the modern, as he said, "representation, freed finally from the relation that was impeding it, can offer itself as representation in its pure form".

The work had an influence on subsequent artists, including Francisco Goya, John Singer Sargent, Pablo Picasso, Salvador Dalí, Richard Hamilton, as well as contemporary video artist, Eve Sussman, who decontextualized it. Édouard Manet was to call Velázquez, "the painter of painters," and Picasso painted fifty-eight interpretations of Las Meninas in a 1957 series, as he exhaustively studied its form, movement, and color.

Oil on canvas - Prado, Madrid, Spain

Self Portrait at the Age of 63

This self-portrait depicts the artist in three-quarter view, facing towards the viewer. Against the dark background, only his furrowed, aging face is illuminated, revealing the wrinkles beneath his eyes and the blemishes on his forehead. As art critic Hilton Cramer noted, the "thickly painted surfaces...are the perfect pictorial correlative" for his "existential candor". Using a deep chiaroscuro, the face is divided between light and shadow by the ridge of the nose, an identifying characteristic of Rembrandt's style.

A leading Baroque painter in the Dutch Golden age, Rembrandt was celebrated for his portraits, his Biblical and classical scenes, allegories, landscapes, genre paintings, and his powerful engravings and etchings. Yet after his death, as art historian Mark Hudson notes, "for almost 200 years...no one was much interested in the art of Rembrandt...the very qualities we admire in him - the earthy truth to physical reality, the directness with which the human presence is put in front of us, the almost edibly palpable feeling for light and shade - were antithetical to the self-conscious classical refinement that dominated critical values in the late 17th and 18th centuries."

Rembrandt was rediscovered in the late-1800s, with the result that he became one of the pre-eminent Old Masters to influence the modern era. His numerous self-portraits, were particularly influential, due to the significant number that he produced throughout his lifetime. Cézanne sketched his Bathsheba at Her Bath (1654), Vincent van Gogh called Rembrandt "a magician", Auguste Rodin described him as a "colossus of art", and Pablo Picasso was to say, "every painter takes himself for Rembrandt". Later artists, including Frank Auerbach and Francis Bacon were deeply influenced by what Auerbach called Rembrandt's "raw truth" and his handling of paint, using thick impasto and expressive loose brushwork. As Hudson wrote, "Yet it is also the trajectory we expect art to take: away from tightness, order and control, towards expressivity and abstraction. As Rembrandt invents himself in paint, so he invents Modern Art as he goes."

Oil on canvas - The National Gallery, London

Beginnings

Medieval Guilds

Beginning in the 11th century, guilds were community-based organizations that held a monopoly on a trade or craft, and by the 12th century they had developed a strict process of advancement. Beginning as an apprentice, entrants would work and study under the direction of a master, an exemplary craftsman, for several years before completing a qualifying work to be certified as a journeyman. Once a journeyman's certificate had been earned, he could freely travel outside the geographical range of his own guild and learn from other masters. Eventually, often after years of study, a journeyman could become a master, but only after completing a 'masterpiece' that was approved by all the masters of the guild. Scottish guild documents contain the first recorded use of "masterstik" (an old Scots word which now translates as masterpiece) in 1570, and the British playwright Ben Jonson used the derivation "masterpiece" in 1605. These master craftsmen rarely signed their works and, as a result, many remain anonymous. Later art historians, identifying a unique style, have tended to name them after the location of their work (the Master of Flémalle) or after a specific piece (the Master of the Brunswick Diptych).

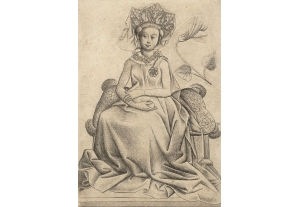

Northern Europe led the way in developing guilds for painters and the first recorded example is the guild of Saint Luke, which was founded in Antwerp in 1382. The guild took its name from Christ's disciple who, according to tradition, painted the first likeness of the Virgin Mary. In other areas, such as in Florence, painters could join the guild of Doctors and Apothecaries, as apothecaries supplied the materials for making paint. They could also join the Compagnia di San Luca (Company of Saint Luke) founded in 1349, a loosely organized confraternity rather than a guild. Despite these variances, throughout Europe, workshops run by a master artist became the dominant mode for art production and the way to obtain an education in art. The noted Italian artist Giotto is thought to have become an apprentice at the age of ten to Cimabue, the leading 13th century master. The tradition of learning from a master continued into the Renaissance and beyond, as shown by Michelangelo's apprenticeship with Domenico Ghirlandaio and Leonardo da Vinci's early study with Andrea del Verrocchio, whose Florentine workshop, as art historian Arturo Galansino noted, shaped "generations of artists".

Art Academies

Art academies played a dominant role in establishing the concept of Old Masters, as they developed a curriculum that emphasized imitating their works, as well as classical Greek and Roman art. The first academy was founded by Cosimo I de 'Medici in Florence in 1562 at the suggestion of Giorgio Vasari, himself an artist and is also considered to be the first art historian. The Accademia e Compagnia delle Arti del Disegno (Academy and Company for the Arts of Drawing) had a dual role, providing an education in the arts as well as overseeing the production of artwork in the city. Along with imitating classical works and the works of those Renaissance masters, who were recognized as equaling or surpassing the classical era, students studied geometry, anatomy and ideas of Renaissance Humanism. The Florentine Academy became the model for subsequent academies, most notably the Accademia di San Luca, founded in the Rome in 1577.

When the French King Louis XIV founded the Académie royale de peinture et de sculpture in 1648 under the influence and leadership of Charles le Brun, it was modeled upon the Accademia di San Luca in Rome and adopted a strict approach to teaching. Students first studied drawing, copying prints of classical Greek sculpture or Renaissance Old Masters, such as Raphael, da Vinci, and Leonardo. Then they studied figurative drawing, copying either classical sculptures or plaster casts, before they could draw from life, sketching a male model. They also studied geometry and anatomy and only after several years were they allowed to paint.

In 1667 the Academy held its first public art exhibition, or Salon. Although initially focused on displaying the work of recent graduates, these annual exhibitions began to include the work of other artists. Over time, the acceptance of paintings into the Salon developed into a prerequisite for artistic success and rejection could ruin a career. The Academy consequently became the arbiters of artistic taste, dictating subject matter, style and even the use of color. This created a genre of painting known as Academic Art, which was heavily informed by the work of the Old Masters. Subsequent national academies, such as the Royal Academy of Art in London and the Royal Danish Academy of Fine Arts adopted the French model, with the result that academic painting dominated Western art, until the early 19th century when Realist artists began to rebel against the system.

In line with these changes in teaching and display, the first recorded use of the term Old Master with its current meaning can also be traced to this period. In 1696, John Evelyn, a noted British diarist, wrote, "My L: Pembroke.shewed me divers rare Pictures of very many of the old & best Masters, especially that of M: Angelo... & a large booke of the best drawings of the old Masters." Evelyn's use of Old Master in this way suggests that it was already a well understood concept by the end of the 17th century.

Women as Old Masters

As art critic Scott Reyburn wrote in 2018, "Unlike contemporary art, old masters (as the terminology implies) also have the problem of being a rigid, male-dominated canon". Yet, from the time of the Renaissance, master artists included women, even though they had to negotiate artistic and societal resistance. Whilst some medieval guilds had an exclusively female membership and others apprenticed women in various crafts and trades, Renaissance Italy discouraged the acceptance of women as apprentices in painting, effectively cutting them off from an artistic career. Sofonisba Anguissola established a rare precedence when she joined Bernardino Campi's workshop around 1546. Praised by Michelangelo, she went on to international success, working for the Duke of Milan before becoming an official painter for King Phillip II in Spain. Her example and her work influenced artists, including Anthony van Dyck who credited her with having taught him art's "true principles".

Despite Anguissola's example, most women obtained their art training through a family workshop. For instance, the Mannerist, Lavinia Fontana, was taught by her father, as were the Baroque masters Artemisia Gentileschi and Elisabetta Sirani. These artists influenced their contemporaries and subsequent artists, as well as pioneering new opportunities for women. The sole financial supporter of her extended family, Fontana was the first woman career artist, and Gentileschi was the first to become a member of Florence's Accademia di Arte del Disegno. Sirani established the first school of painting for women, which was attended by the noted artists Veronica Fontana, Lucrezia Scarfaglia, and Ginevra Cantofoli.

In the Rococo period, Élisabeth Louise Vigée Le Brun was famous for her vibrant portraits, and Angelica Kauffman became a leading master of the Neoclassical era, known for her history paintings. Le Brun was an official artist of the French court, and Kauffman was a founding member of the London Royal Academy. Judith Leyster was highly successful during the Dutch Golden Age. Following her death, however, most of her works were attributed to either her husband Jan Miense Molenaer or to Frans Hals. Her work was only correctly attributed in 1893. By the 19th century, many women masters were forgotten; their work was not exhibited and they were often left out of art history. The Feminist Movement in the 1970s did much to rediscover many of these pioneers, although as Sotheby's noted during their 2019 "The Female Triumphant" sale during Masters Week, "Nearly 50 years later, the stories of the remarkable women who did break boundaries to achieve artistic acclaim are just beginning to be told".

Concepts and Trends

Innovation

Due to the extensive time covered, the term Old Master encompasses a diverse range of styles and movements. Throughout the period, however, the fundamental approach to Western art was representational. As a result the classical principles of proportion and perspective remained dominant. The most famous Old Masters were tireless innovators, developing or elevating new techniques, stylistic elements, and subject matter. Da Vinci's oil paintings were celebrated for their original use of chiaroscuro and his invention of sfumato, the use of many layers of glaze to create subtle tonal gradations, whilst Pieter Breughel the Elder's works elevated genre scenes and landscapes to high art. The desire to equal and surpass previous masters also drove the development of new stylistic approaches. Some scholars view Mannerism's innovative use of elongated shapes and flattened space to produce new and powerful images as compelled by the desire to escape the tight rules of symmetry and ratio displayed by da Vinci, Michelangelo, and Raphael, and other High Renaissance artists.

Old Master Prints

An old master print generally refers to a print made from the early 1400s to 1830 either by an old master artist as an original work of art or as a means of reproducing artworks for wider dissemination. The Master of the Playing Cards, an anonymous German engraver from the early 1400s, is described by the Metropolitan Museum of Art as "the first great figure in the history of engraving". His name is derived from 77 surviving prints, depicting a set of playing cards, the earliest known set of intaglio plates.

Printmaking, a dominant art mode in Northern Europe by 1430, quickly spread throughout the rest of Europe. In Italy, it was adopted by Andrea Mantegna, who was one of the first Italian painters to use engraving for the creation of original work as opposed to a medium for reproduction. Albrecht Dürer's international reputation was based primarily upon his innovative prints, which reached a wide audience throughout Europe and had an enormous impact on his contemporaries. By the 16th century, many artists including Raphael, Titian, and Perugino had become interested in printmaking, particularly prints that reproduced their paintings and made the images more easily available throughout Europe.

Little Masters

The term Little Masters describes a German group of engravers who, working from around 1525 to 1550, created miniature prints. Sometimes no larger than postage stamp size, these works were celebrated for their fine detail. Albrecht Dürer and Italian Renaissance artists influenced most of the leading members of the group, including Albrecht Altdorfer, Hans Sebald Beham, Barthel Beham, George Penz, and Heinrich Aldegraver. They depicted scenes from the Bible and classical mythology, landscapes, and scenes of peasant life, combining the refinement of Italian art with German design. In Germany these small prints were much in demand by nobility and wealthy merchants who displayed them in Kunstkammers, or curiosity cabinets.

Drawing

Drawing was an essential part of guild training, as students were expected to master it before moving onto painting. The wider use and production of drawings by Old Masters, however, tended to reflect more localized trends. In Protestant Holland, where art was made for the wealthy middle classes, sketches of genre scenes and landscapes were seen as art in themselves, whereas in Italy, where the Catholic Church commissioned most art, drawings were often preliminary studies or cartoons for large frescos. As drawings and cartoons were portable, they were often the available examples of master works and studied and imitated by art students throughout Europe. Museums, such as the British Museum, the Louvre, and the Rijksmuseum, built extensive collections of drawings, and art auction houses often feature sales of Old Master drawings. As drawings by exemplary Old Masters are infrequently available, works by lesser-known Old Masters have become highly valued. In 2018 Christie's sold a figure study by Lucas van Leyden for almost 11.5 million pounds. As art historian Furio Rinaldi noted, making "Van Leyden, alongside Raphael...only the second Old Master artist ever to have a drawing sell for more than £10,000,000".

Art Museums

From the 18th century, museums played a leading role in promoting Old Masters, as they based their collections on these works. Known for its Old Masters collection, Dresden's Gemäldegalerie Alte Meister, (Old Master Picture Gallery) is one of the earliest. The King of Poland, August the Strong, began collecting notable European works in the late 17th century, and the collection expanded under the direction of his son August III to include Dutch, Flemish, and German masters. Visiting the museum in 1768, the German writer Wolfgang von Goethe exclaimed, "I entered this shrine, and my amazement exceeded any preconceived idea". The museum became a model for museums that opened in the late 18th century, such as the Musée du Louvre (1793). Visitors were primarily drawn from the upper classes but also included students and artists who wanted to study and copy the collection's masterworks. This is demonstrated by the Louvre's policy of setting aside five out of every ten days for artists.

Art Auction Houses

Demand by museums and collectors for works by Old Masters played an important role in the rise of art auction houses. The earliest auction houses emerged in Sweden, with the Stockholm Auktionsverk founded in 1674, and the Uppsala auktionskammar in 1731. London followed soon after with Baker and Leigh, which later became Sotheby's, founded in 1744, and Christie's in 1766. Continuing into the modern era, these auction houses have expanded internationally, with offices in major cities around the world.

In the contemporary art market, as New York Times critic Scott Reyburn notes, "one of the biggest challenges facing the art world...[is]...How can interest in older art be sustained when so much more attention is focused - and so much more money is spent - on contemporary works?" To draw attention to the Old Masters, auction houses hold events like Old Masters week to highlight the works, though, as many of the eminent works are already housed in museums, the offerings are often of lesser-known artists. As Reyburn described in summer 2017, "Last week in London, Sotheby's and Christie's evening sales offered a combined total of 131 pictures by artists born before 1850. More than half of them were either unknown, or unknown to anyone who had not studied art history." When, rarely, a work by a famous Old Master does come up for auction, it, not only, drives prices but also becomes a cultural phenomenon. In New York in 2017 Christie's sold Leonardo da Vinci's Salvator Mundi (c. 1500) for a record-breaking $450.3 million.

Later Developments

As art historian Nancy Locke wrote, "The list of famous artists whose documented admiration of, and copies after the Old Masters is endless; Landseer after Rubens; John Singer Sargent after Velasquez; Henri Fantin Latour after Titian and Veronese, Géricault after Caravaggio and earlier; Watteau after Titian, Van Dyck after Tintoretto, Matsys after Raphael, to name but a few." Yet, even though art students still study and imitate the Old Masters today, the strict curriculum of the academy began to fall out of favor in the 1800s, as Realism, the first modern movement, emphasized observation of nature and realistic depictions of working class life.

Even so, leading artists have continued to return to the Old Masters, often referencing them in their own works. Manet's Olympia (1863) referenced Titian's Venus of Urbino (1538), and Degas often visited the Louvre to copy and sketch the works of Ingres and Poussin. As Nancy Locke wrote, Paul Cézanne "felt a deep reverence for certain artists in the Louvre, and frequently turned to them for inspiration and guidance, even in his maturity". Cézanne, as Locke noted, "wrestled with his predecessors on the way to transforming them" and 20th century modern art movements were often marked by a drive to supersede, reconfigure, or actively reject the influence of past masters. Picasso, for instance, devoted a huge amount of time to reworking Cranach, Velázquez, Delacroix, Manet, and Degas. In 1919 Marcel Duchamp's defaced a reproduction of the Mona Lisa (1503-1507) with a mustache, to produce L.H.O.O.Q., whilst Andy Warhol's The Birth of Venus (1984) was a cropped and flattened close-up of Botticelli's work.

In the 1970s the emerging Feminist Art movement challenged the tradition of the Old Masters, arguing the emphasis had erased women artists from art history, education, and patronage. Linda Nochlin's "Why Have There Been No Great Women Artists?" (1971) questioned the traditional assumption that great masters were exclusively European ma, while the Guerrilla Girls in the 1980s challenged art museums to exhibit more women artists, including those like Judith Leyster and Artemisia Gentileschi, renowned as masters in their own eras but subsequently erased.

Subsequent artists have continued to reconfigure the Old Masters. As art critic Magda Mihalska wrote, Cindy Sherman's Old Masters (1989-1990) series of thirty-five photographs "blends Post-Modern consciousness with timeless masterpieces (or tropes that they represent) of European masters". Kehinde Wiley, as art critic Anne Quito noted, "Cribbing from titans of Western art like Jacques-Louis David, Édouard Manet, Jean-Auguste-Dominique Ingres and Titian...creates hyper-realistic portraits, imbuing his subjects with the similar air of dignity or vainglory found in old paintings". On the other hand, the Chapman Brothers, directly altered original artwork including a rare set of Francisco Goya's prints in Insult to Injury (2004).

Ask The Art Story AI

Ask The Art Story AI