Summary of Photomontage

Photomontage is an artistic practice that has endured almost since the birth of photography itself. At its most basic level, the photomontage is a single image combined of two or more original and/or existing images. The artist in question produces a montage in order to encourage their audience to think about the relationship between the grouped images. The photomontage will be achieved by cutting and pasting, while original or found photographs can often be placed next to non-photographic images (such as written text and even patterns and shapes). A "new" image might also be created by altering an original photograph through tearing and cutting. In every instance of this artistic approach the viewer is required, be that consciously or unconsciously, to make sense of an original artwork composed through image associations.

Key Ideas & Accomplishments

- From its very earliest examples, photomontage has been the medium of choice for producers of propaganda and agitprop. The political posters of the Dadaists and the Constructivists chose the photographic image above all others because the photograph communicates with an objectivity that can be lost with painting and written text. Indeed, photomontage can produce a unique, attention-grabbing, dynamism that is perfectly suited to the goals of propagandists.

- Once adopted by the Surrealists photomontage, which allowed for artists to experiment with the idea of "automatic" (or chance) free association, was used to explore the potential for creating incredulous and uncanny relations. Indeed, Surrealism effectively unshackled photomontage from its propagandist function and in so doing it widened the appreciation of the art form amongst an audience that wondered at the range of its new creative possibilities.

- Contemporary artists, such as Jeff Wall and Andreas Gursky, have exploited the boundless possibilities of digital technology to create transparent and seamless images out of multiple photographic exposures. In this respect, their images pay homage to the very earliest form of "combination printing" though in these contemporary works technology has allowed the artist to blend different geographical sites and settings into whole new localities.

- Pop artists brought photomontage closest to the fields of collage and contemporary photographers such as Lorna Simpson and John Stezaker, have extended the collage effect beyond ironic playfulness. Their "photocollages" draw attention to the seams between images with the goal of creating more intangible and more conceptual impressions amongst their audiences.

The Important Artists and Works of Photomontage

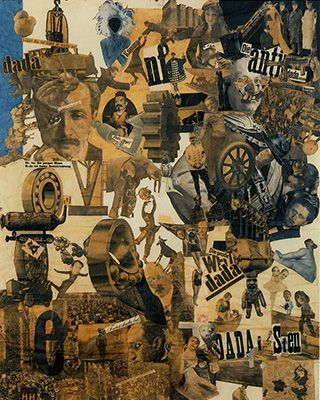

Cut with the Dada Kitchen Knife through the Last Weimar Beer-Belly Cultural Epoch in Germany

Composed of clippings from mass media, this large photomontage combines images of industrial machines, leading contemporary figures, and text, in disruptive but ironic juxtapositions. Implicitly commenting upon Weimar society, the work assembles images of establishment figures around the phrase "anti-dada" while various anti-establishment radicals and artists cluster around the word "DADA". The asymmetrical composition reflects both the chaos of World War I, and the anarchic opposition borne of its aftermath. At the same time, the image wryly challenges gender inequities, as a small map in the lower right shows the only countries that allowed women the vote. As art critic Laura Cumming wrote, "female acrobats leap and tumble among the soldiers, guns and plutocrats [resulting in] a juggling act of bristling vitality". For her part, Höch described herself as a "photomonteur" (photo-mechanic): "our whole purpose was to integrate objects from the world of machines and industry in the world of art" she said.

This work, emblematic of the Berlin Dada movement, was hailed at the First International Dada Fair in 1920 (though initially Grosz and Heartfield rejected Höch's inclusion and only softened their position on the advocacy of Höch's lover and artistic collaborator, Raoul Haussman). Like other women artists of her era, Höch was largely overlooked. She was "rediscovered" following the Museum of Modern Art's 1968 exhibition, Dada, Surrealism and their Heritage. Critic Brian Dillon added that Höch's "innovative presence has survived in the work of later monteurs: in the laconic and unsettling incisions practised by John Stezaker, in the pointed assault on images of women and commodities in the work of Linder Sterling, and more recently in the playful grotesques of the late Polish artist Jan Dziaczkowski".

Collage of pasted papers - Nationalgalerie, Staatliche Museen zu Berlin, Berlin, Germany

Self-Portrait (The Constructor)

This photomontage, which combines elements of collage, drawing, and the photogram, depicts El Lissitzky, looking fixidly forward, while his right eye seems to look through the center of his open palm. The same hand balances a compass over one of his graphic works, partially depicted, on the left side of the frame. The work conveys the unity of artistic vision and execution and suggests the artist is both the constructor of his work and is constructed by it.

A leading figure in Constructivism, El Lissitzky's work incorporates the movement's emphasis upon mathematical form and geometric grids. It is also considered a pioneering example of New Vision photography. As the Museum of Modern Art described it, "The essence of New Vision photography is pointedly expressed in this picture [...] which puts the act of seeing at center stage [...] insight, it expresses, is passed through the eye and transmitted to the hand, and through it to the tools of production".

Lissitzky created a number of photomontages in the early 1920s; each noted for its elegant multilayering. Photographic archivist Klaus Pollmeier, who conducted an in-depth study on behalf of the Museum of Modern Art, wrote, "despite the relative paucity of his means, what remains remarkable to the close observer of Lissitzky's photographic images is that the artist does not at all appear to have felt constrained. He seems to have visualized many aspects of the final image before the exposure of the negative in the camera, compensating for the shortcomings of his limited technology with a sharp and almost boundless imagination".

Gelatin silver print - Victoria and Albert Museum, London

Massenpsychose (Mass Psychosis)

This photomontage portrays various figures, alone or in groups, as if placed within three shapes, resembling test tubes. At lower left, a group of African men huddle in a linked ring, while atop the test-tube a woman aims a rifle at an anatomical diagram of a man (we know this as he is wearing a trilby hat) in the adjacent test-tube. Above the man, another man aims a billiard cue at a huddled group of women, while in the upper test tube, a German officer stands as if surveying a military parade. The juxtapositions are disconcerting and arbitrary, though connected by a sense of potential violence and arbitrary social forces, informed by gender and race.

Making this image while he was teaching at the Bauhaus (between 1923 and 1928), Moholy-Nagy called his photomontages "photoplastics" and defined them as "a compressed interpenetration of visual and verbal wit". Also called In the Name of the Law, this work was prompted by events in Vienna in 1927 when police killed 89 protestors in a crowd that stormed parliament. Influenced by the Dadaists (he made his first photomontages while sharing a studio with Kurt Schwitters in the early 1920s) Moholy-Nagy has placed his figures, cut from magazines, within a Constructivist schema. As art critic Andy Grundberg noted, his "use of photomontage remains distinctive not because he originated the form but because of what he did with it. Just as his theoretical program was distinct from those of the Dadaists and the Constructivists, so, too, was his imagery. The Dadaists were satirists and the Constructivists were social idealists; Moholy, a romantic who managed to be both a utopian and a pragmatist, was able to span both positions, and more".

Photomontage - George Eastman House, Rochester, New York

Adolf the Übermensch: Swallows gold and spouts junk, AIZ 11. no. 29, July 17

This photomontage, published in the year that Adolf Hitler became the Chancellor of Germany, depicts Hitler delivering one of his heated speeches. Combined with an x-ray image revealing the ribs and oesophagus filled with gold coins, the portrait blatantly attacks the Nazi leader's hollow rhetoric.

As a committed leftist, Heartfield made this image, one of several, for Arbeiter Illustrierte Zeitung, a daily paper for left-wing workers. This well-known piece shows the artist's disdain for the corporate greed of Germany's industrial barons and the hypocrisy of the Nazi Party's anti-capitalist declarations. Unlike the chaos of Höch's images, Heartfield's photomontages were seamless in their presentation of a single message. He designed this work for widespread reproduction, and it was displayed throughout Germany, which led to his being hunted down by the Nazis before managing to escape into exile. He also initiates the reference to classical artworks, as this image draws upon Honoré Daumier's Gargantua (1831) a famous and controversial political cartoon that depicted the French King Louis-Philippe I as the greedy giant of Rabelais's story of gluttony.

The famous left-wing playwright Berthold Brecht called Heartfield "one of the most important European artists [who had] created himself, the field of photomontage". The social and political impact of Heartfield's images has also inspired subsequent artists. In addition to Martha Rosler, Jo Spence, and Peter Kennard, Heartfield's influence is most evident in the work of Thomas Ruff whose 1996 Plakats (Posters) series of photomontages attacks contemporary politicians and their support for nuclear weapons. Today, as art historian Nancy Roth commented, "renewed interest in Heartfield is associated with a broad reconsideration of modernism itself. He offers, among other things, an entry point into a 'lost,' or profoundly obscured body of thought about what art might be and what it might accomplish in a democratic society".

Offset - Getty Research Institute, Los Angeles, California

Untitled (Shell/Hand)

This image depicts a shell from which a woman's hand has emerged like a living sea creature, illuminated eerily as it lies on a beach, one finger probing the sand, as the sky roils with dramatic light above. This Surrealist photomontage incorporates elements of fashion photography, as the high finish of the image and its lighting suggest a glamour shot, enhanced by the shell's spiraling pattern, and the graceful curve of the well-manicured hand. Unlike most artists who employed photomontage, Maar did not source clippings from publications, but used rather only her own photographs. The result was images that seem to be a real shot of an impossible dream-like scenario. As art critic Jenny Uglow wrote, Maar's "images are powerful, haunting, stylish [...] suggesting her fascination with dreams and the unconscious. The human body and the social realm are rearranged and the natural world flowers with a buried energy".

In the early 1930s, Maar's photography incorporated street photography, double exposures, and photomontage, into her commercial studio work. She was actively involved in both the artistic projects and political actions of the Surrealists, and her photograph Portrait of Ubu (1936), showing a cropped close-up of an unidentified creature that is now thought to be an armadillo fetus, became an iconic image of the movement. As art critic Joseph Nechvatal wrote, "Maar's photographic experiments reject the pretense of naturalism in straightforward photography and attempt to achieve something much deeper than resemblance". Often overlooked (as she was known primarily as Picasso's lover and muse) Maar's work is undergoing a contemporary revival - including a retrospective at the Tate in 2019-20.

Gelatin silver print - Musée national d'art moderne, Centre Pompidou, Paris

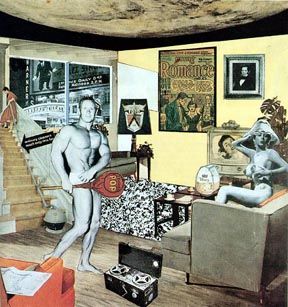

Just What Is It That Makes Today's Homes So Different, So Appealing?

Though more readily associated with a group of 1960s New York artists, including Andy Warhol and Roy Lichtenstein, Pop Art emerged first in Britain during the economically depressed post-war years of the 1950s. Hamilton's photomontage, featuring found images of comic books, pin-ups and various consumer durables, pre-empted many of American Pop Art's most enduring motifs. Hamilton, and others including Eduardo Paolozzi and Peter Blake, turned their inquisitive (envious?) gaze to America's abundant consumer culture and used the marketing language of post-War Americana to produce new and irreverent images using collage and photomontage. Hamilton's image was intended as both a commentary and celebration on Western consumer culture: "We seemed to be taking a course towards a rosy future and our changing, Hi-Tech, world was embraced with a starry-eyed confidence; a surge of optimism which took us into the 1960s", he observed.

Many critics have cited Hamilton's iconic image as signaling the birth of postmodernism. Through its celebration of kitsch, ephemera and disposable objects, Pop Art rejected the high modernism of Abstract Expressionism and the virtues of abstraction - and its detestation of everything kitsch - as espoused by Clement Greenberg. Indeed, Hamilton described Pop Art thus: "Popular. Transient. Expendable. Low cost. Mass produced. Young. Witty. Gimmicky. Glamourous, Big business."

Hamilton made this work for the 1956 This is Tomorrow exhibition which showcased the collaborative efforts of the London School. As art historian Elizabeth Manchester observed, the aim of the exhibition was to create "a sort of funfair vision of the future where sensual perception was stimulated and confused and images culled from a range of sources formed an iconography for the modern world". Hamilton's image was used for the catalogue's cover and other publicity ephemera.

Collage - Kunsthalle Tübingen, Tübingen, Germany

Red Stripe Kitchen

Produced at the height of the war in Vietnam, this somewhat incredulous photomontage combines an image of a high-tech kitchen with images of two soldiers surveying the ground as they search for explosives. Rosler's innovative photomontage functions on several levels, challenging the viewer to consider the relationship between consumer society, gender and class stratification, and the military industrial complex. As art critic William J. Simmons wrote, Rosler's "combination of pristine scenes from design magazines with photographs of war makes explicit the connections between a specifically gendered iteration of capitalism and global conflict".

This work is from one of Rosler's most famous series, House Beautiful: Bringing the War Home, (1967-72). As Rosler said of the collection, "We were looking at this war every single night at dinner time on our TVs, which is why it's called the 'living-room war.'...I was interested in a visual means of fighting something imposed on us visually, and what I thought of doing was taking these damn news photographs and putting them on images of our living rooms, which is where we actually saw the footage. It was in our homes, which were supposedly safe and far away".

Printing out her photomontages as flyers on a drug store Xerox machine in New York, she saw her images as more effective agitprop then the prevalent text-based anti-war flyers. Rosler was to revisit the series in Bringing the War Home: House Beautiful, (c. 2004-08), photomontages that this time opposed the war in Iraq. Commenting on the later, critic William J. Simmons wrote, "This reinvigoration of House Beautiful is not a revision [...] Her return to the photomontage technique, despite the advent of Photoshop, insists there is something essential about the medium itself that works in tandem with a continued critique of war".

Photomontage, printed as a color photograph - The Solomon R. Guggenheim Museum, New York, New York

The Oath

This image depicts a courtroom trial, though the judicial setting is partly concealed by a colored postcard that shows a ruined temple overlooking the blue Mediterranean as the sun rises or sets on the horizon. At the lower right of the frame, a smartly-dressed woman raises her right hand as she takes her oath, while on the left, three men stand in the dock: a lawyer reading something on a piece of paper, a man (probably the accused given the concerned look on his face) and a French policeman standing just behind him. The postcard evokes the origins of Western civilization and law as the lines of the temple and the horizon align with the courtroom's railings and panelling. The postcard seems to extend from the courtroom scene as the woman's right hand vanishes into the marble column marking the postcard's edge. The art historian Elizabeth Manchester suggested that "the postcard scene as an alternative view of the narrative between the two characters that bracket it - the woman who is making the oath, and the accused whose fate depends on her words".

In 1976 Stezaker pioneered the use of film stills to create photomontages, though he prefers to call his work "collage," as he said, "I've always made a distinction between collage and photomontage. Montage is about producing something seamless and legible, where collage is about interrupting the seam and making something illegible". While studying at the Slade School of Art, Stezaker became influenced by Guy Debord's Society of the Spectacle (1970) a foundational text of Situationist International, emphasizing détournement, as a means of overturning or repurposing existing images and media. He first began to use film stills to make what he called "incisions," as he cut away part of the film still, before developing his "inserts," where he combined a postcard with a film still. This image is part of The Trial, a series of four images, each combining a single black and white still with a postcard, containing water imagery.

As Manchester added, "Stezaker's water images relate to the Romantic tradition of the late eighteenth and early nineteenth centuries when nature was viewed as sublime. His juxtaposition of this type of imagery [...] with the human drama depicted in a 1940s film still arouses a sense of the uncanny [...] Stezaker's additions to film stills may be understood as poetic visualisations of aspects of people and their relationships that are not normally visible to the human eye".

Postcard on paper on photograph, black and white, on paper - Collection of the Tate, United Kingdom

Haywain with Cruise Missiles

In the years between the end of the Second World War and the start of the Cold War, photomontage fell out of favor with a public tiring of imagery that seems positively bland when compared to the new wonders of television. Photomontage underwent a revival during the 1980s and the rise of the CND movement. Photomontage served a practical purpose at it adorned banners designed to be waved during demonstrations. Kennard was amongst those who decried painting's lack of immediacy and whose work was designed to cast light on the "unrevealed truth" of the nuclear arms race.

This photomontage juxtaposes/blends photographs of American cruise missiles with a reproduction of John Constable's iconic landscape Haywain (1821). In the bucolic pastoral, the horse drawn cart crossing a river near a mill is now freighted with three nuclear warheads, pointing up at the sky as if in launch position. Kennard's photomontage repurposed a famous artwork and, by "loading" the landscape, traditionally identified with British identity and culture, with American weaponry, he made an immediate political and artistic statement. This work was created in response to the deployment of American cruise missiles in Britain under Margaret Thatcher's government, as the artist created a number of photomontages for the Campaign for Nuclear Disarmament, including a series of posters, Target London (1985), commissioned to support the declaration of London as a "nuclear-free zone".

Kennard began his career as a painter, studying first at the Slade School and then the Royal College of Art. But influenced by the political uprisings of the time, he said that "after the events of 1968 I began to look for a form of expression that could bring art and politics together to a wider audience [...] I found that photography wasn't as burdened with similar art historical associations". As art critic Richard Slocombe added, "Peter Kennard is without doubt Britain's most important political artist and its leading practitioner of photomontage. His adoption of the medium in the late 1960s restored an association with radical politics, and drew inspiration from the anti-Nazi montages of John Heartfield in the 1930s. Many of Kennard's images are now themselves icons of the medium, defining the tenor of protest in recent times and informing the visual culture of conflict and crisis in modern history".

Chromolithograph on paper and photographs on paper - Collection of the Tate, United Kingdom

Pearblossom Hwy.11 - 18th April 1986, #2

This photomontage depicts the view along a desert highway, replete with road signs, Joshua trees, and litter. The joined Polaroids create different effects, as the pavement breaks and disappears into the surrounding sand, and suggest the shifting vision of someone on a road trip. As art critic Arielle Budick wrote, Hockney "has spent much of his career trying to render the world the way we actually register it, full of panoramic distractions and strobing detail". For his part, Hockney wrote that the "picture was not just about a crossroads, but about us driving around. I'd had three days of driving and being the passenger. The driver and the passenger see the road in different ways [...] And the picture dealt with that: on the right-hand side of the road it's as if you're the driver, reading traffic signs to tell you what to do and so on, and on the left-hand side it's as if you're a passenger going along the road more slowly, looking all around".

In the 1980s, Hockney began making what he called "joiners," photomontages composed of multiple Polaroid prints (he later made them with multiple photographs). Rather than merging into a seamless composite, the joiners become a patchwork; a kind of Cubist work that for Hockney conveyed how human vision actually worked. He discovered the technique after gluing Polaroid shots of a Los Angeles house together to plan the composition of his painting and described the act of "joining" as more equivalent to drawing than photography given that the images created a layered effect of different human perspectives. As Hockney said, "The moment you make a collage of photographs it becomes something like a drawing [...] Because there is no single way to join them. If you make a decision about something like that, isn't that exactly what you are doing when you are drawing? It seems to me it is. So collage itself is a form of drawing. I always thought it was a great, profound invention of the 20th century. It's putting one layer of time on another, isn't it?".

Chromogenic print - J. Paul Getty Museum, Los Angeles

Untitled (Your body is a battleground)

This iconic image is split vertically between a positive and a negative image that creates a kind of literal "battle line," dividing the woman's face, its impact enhanced by the bold red that frames the image on both sides. Three red rectangles with large white text march vertically down the page, reading from top to bottom, and creating a powerful message that arrives both as a statement of fact and a voice urging inner awareness, as the "your" form of address includes the viewer.

Kruger made this work for the 1989 Women's March on Washington to support legal abortion prior to the Supreme Court hearing a case that the Bush administration hoped would overturn women's right to choose, and like a number of her works, it became instantly recognizable but also controversial. When she began making photomontages in the early 1980s, Kruger's signature style - white text on a red background combined with a black and white image from mass media publications - drew upon her previous experience as a graphic designer and picture editor for various Condé Nast publications. While her work often challenges societal assumptions, it is fundamentally conceptual. As she said, "I work with pictures and words because they have the ability to determine who we are and who we aren't".

Photographic silkscreen on vinyl - The Broad, Los Angeles

A Sudden Gust of Wind (after Hokusai)

Evoking Travellers Caught in a Sudden breeze at Ejiri (c.1832), a woodcut by the famous Japanese artist Katsushika Hokusai, this image depicts four figures in the foreground, frozen in motion, as they are caught by a gust of wind. Containing only two trees, bent by the wind, the flat landscape is barren, almost industrial with its telephone poles, industrial pipes, and its canal dug out for agricultural purposes. Though all four figures are crossing the direct embankment, they are disconnected from each other, creating a tableau of displacement. The work is an early example of digitally created photomontage, its complexity combining Wall's photographs of the four actors, taken over several months then blended into one seamless, hyper-realistic image.

Originally trained as a painter, Wall began to work on various film projects in the early 1970s. In 1977 he pioneered a new form of art, using a light box to display large photographic transparencies, which he described as "the perfect synthetic technology". As he said, "It was not photography, it was not cinema, it was not painting, it was not propaganda, but it has strong associations with them all". Wall became well-known for these large light box images which were initially often based upon classical artworks. As art historian Elizabeth Manchester wrote, "In common with film, the image on a light box relies on a hidden space from which light emanates to be seen. Wall believes that this inaccessible space produces an 'experience of two places, two worlds in one moment', providing a source of disassociation, alienation and power".

Transparency on lightbox - Collection of the Tate, United Kingdom

Riunite & Ice #20

This photomontage depicts three partial images of an African American fashion model. Though fragmented, the pictorial juxtaposition creates a relationship between the images as if they were aspects of one self. In each image, expensive jewelry makes an elegant fashion statement, attracting the viewer's attention to the juxtaposition of portraits, prompting questions of identity. On the right, the woman smiling as she faces the viewer seems to emerge from the thoughts of the woman depicted in profile while the merging of their hair suggests some kind of whole. The work conveys the artist's preoccupation with what she described as, "The notion of fragmentation, especially of the body [which] is prevalent in our culture. We're fragmented not only in terms of how society regulates our bodies but in the way we think about ourselves".

A leading conceptual photographer since the 1980s, Simpson's photomontages combined the medium with painting, as seen here in the black and white smoke that fills an inverted triangle created by the placement of the images. In her 2018 installation Unanswerable, which contained over forty photomontages, Simpson described her inclusion of natural elements as symbolizing the forces filling the gap of Black history. She explained her use of images from the black fashion magazines from the 1950s to the 1970s, Jet and Ebony, thus: "They informed my sense of thinking about being black in America and are both a reminder of my childhood and a lens through which to see the past fifty years of history." Art critic Teju Cole argued that Simpson's work "is simultaneously about the 'neutral' space of ideas and the particularized experience of the body [what] Simpson calls "the push and pull of photography", that being, the "stuttering potential inherent in mechanical reproduction and the imperfect registrations that mirror subconscious life".

Collage and ink on paper - Lorna Simpson studio, New York, New York

Beginnings

Photomontage first emerged in the mid-1850s as experimental photographers aspired to create images that could rank alongside fine art. The idea of the composite image was thought to have been first proposed by the French photographer Hippolyte Bayard who wanted to produce a balanced image in which the subject was superimposed on a background that brought the two together in an idealized setting. Since a photograph was regarded as the record of truth, however, his approach attracted controversy amongst the photographic community who did not warm to the blatant misrepresentation of reality.

The first commercial photomontages were produced during the mid-Victorian era when the practice was given the name "combination printing" by Oscar Gustave Rejlander, a self-appointed artist in this new field. Rejlander started working in portraiture, but he also created notorious "erotic" artworks featuring circus models and child prostitutes. His famous Two Ways of Life (1857) combined over thirty images in a single photograph to create a moralistic allegory contrasting a life of sin with one of virtue. Showing two boys being offered guidance by the patriarch, the print initially caused controversy for its partial nudity. That objection notwithstanding, the print was a success and helped secure Rejlander's admission into the Royal Photographic Society of London.

Like Rejlander, Henry Peach Robinson started out in portraiture, and, like Rejlander, he was considered one of the most influential photographers of late nineteenth century. His most famous composite print, Fading Away, depicted a young woman's final moments with her loved ones in attendance. The image belongs to what Robinson called his "Pre-Raphaelite phase" in which he sought to manufacture timeless moments in a gothic setting.

Though Rejlander and Robinson aspired to the status of fine artists, many less distinguished photomontages came to fruition during the same period. These tended to take the form of novelty postcards featuring the wrong head stuck on the wrong human body, or even a human head placed on the body of a creature. By the beginning of World War I, more sober images in Robinson's sentimental/illusionist style gained in commercial popularity as photographers across Europe produced postcards showing soldiers departing for battle with their loved ones waving them off. These postcards, very often hand-tinted, would have an impact on the development of photomontage within the Berlin Dada movement which steered a path away from this false narrative tradition towards something much more self-reflexive.

Concepts and Styles

Dada

Dada artists are usually credited with pioneering the use of "non-narrative" photomontage. (Not without a little conceit) George Grosz reflected that "When John Heartfield and I invented photomontage in my South End studio at five o'clock on a May morning in 1916, neither of us had any inkling of its great possibilities, nor of the thorny yet successful road it was to take". Hannah Höch, meanwhile, explained how she and her partner Raoul Hausmann came to adopt the idea, not from Heartfield or Grosz, but "from a trick of the official photographers of the Prussian army regiments [who] used to have elaborate oleo-lithographed mounts, representing a group of uniformed men with a barracks or a landscape in the background then inserted photographic portraits of the faces of their customers, generally coloring them later by hand". Though these commercial efforts were intended to create a seamless illusion, Höch used the technique rather to draw attention to the absurdities and inequalities of modern German society.

Photomontage would become a dominant technique within the Berlin Dada movement, redefining the very role of the modern artist (as the Dadaists saw it at least). As Raoul Hausmann said, "We called [the] process 'photomontage,' because it embodied our refusal to play the part of the artist. We regarded ourselves as engineers, and our work as construction: we assembled our work, like a fitter". The art critic Brian Dillon added that the technique established "the aesthetic of liberation, revolution, protest [...] And in the hands of these artists it became intensely ideological, a defence in times of tyranny and a weapon against injustice".

Constructivism

The idea of photographic formalism was the central tenet of Constructivism, and as art historian Craig Buckley remarked, while the "beginnings of avant-garde photomontage are commonly traced back to the context of Berlin Dada after World War I [...] the technique was adopted almost simultaneously by constructivist artists and filmmakers in the Soviet Union".

El Lissitzky, Alexander Rodchenko, Gustav Klutis, Valentina Kulagina, and Varvara Stepanova (who defined photomontage in 1928 as "the assemblage of the expressive elements from individual photographs") created photomontages that synthesized images with graphic design to support the Russian Revolution and the new Soviet Government. Constructivist works were inherently propagandist, as exemplified in Rodchenko's posters which, with their bold colors and dynamic geometric design, transformed the art of graphic design into something revolutionary. El Lissitzky's photomontages, which combined his photographs in multi-layered compositions, exemplified a more aesthetic Constructivist approach, while also influencing the New Vision movement, Bauhaus photography, and prominent artists such as László Moholy-Nagy.

Surrealism

Photomontage was valued amongst Surrealists for its ability to create uncanny scenarios that disturbed and provoked by probing the human subconscious. Former Dada artists, such as Max Ernst, carried the technique over into the new movement. Ernst described photomontage as "the systematic exploitation of the accidentally or artificially provoked encounter of two or more foreign realities on a seemingly incongruous level - and the spark of poetry that leaps across the gap as these two realities are brought together". Surrealism also pioneered collaborative photomontage through the cadaver exquis (exquisite corpse) technique whereby the various participants contributed to the piece while remaining unaware of the origins of the previous contribution. Some Surrealists, such as Dora Maar, were known primarily for their photomontage, though many leading Surrealists, including René Magritte, Man Ray, and Salvador Dalí included the technique in their repertoire. Their works also exercised an important international influence, as seen, for instance, in Harue Koga's Sea (1929) which helped pioneer Surrealism in Japan. He too used the collage technique to create what have been called "photomontage paintings".

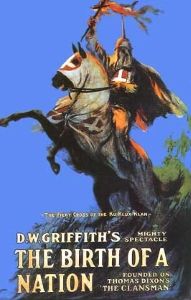

Cinema - The Montage of Moving Images

Between 1899 and 1909 the grammars of cinema entered a chaotic period of experimentation in which filmmakers hurried to test the possibilities of editing individual shots of film together into something more meaningful. Between 1909 and 1919 one D. W. Griffiths almost singlehandedly developed the method of montage that gave rise to the Classical Realist Narrative; known otherwise as the Classical Hollywood Film. A profoundly problematic figure for historians given his supremacist and pious worldview, through films like The Birth of a Nation (1915) he devised a system of montage that was so sophisticated he placed the spectator in the world of a feature length film; side-by-side the heroes and heroines that drive that narrative. With Griffith, the phenomenon of modern cinema-going was duly born.

Just as the modernists had responded to the illusionism of "combination prints", the Dadaists, Constructivists and Surrealists all produced films that challenged the Classical Narrative system. In Russia (and in awe of Griffith's achievements) filmmakers such as Sergei M. Eisenstein and Dziga Vertov experimented with alternative methods of film montage. Eisenstein developed five stages of montage - metric, rhythmic, tonal, over tonal, intellectual - that combined to bring a revolutionary dynamism to filmmaking: "the fact [is] that two film pieces of any kind, placed together, inevitably combine into a new concept, a new quality, arising out of a juxtaposition" stated Eisenstein in his famous treatise on montage The Film Sense.

Probably the most famous (and certainly the most notorious) of the early art films was the 17 minute Surrealist masterpiece Un Chien Andalou (1929), by Luis Buñuel and Salvador Dalí. There is no temporal or spatial relationship between scenes with seemingly random and startling set pieces spliced together on the principle of a dream logic. Indeed, the film only touches on the idea of a coherent narrative through the continued presence of the same actors and the somewhat sparse use of motifs (striped objects for instance). By juxtaposing individual scenes, "dreamed up" independently by the two artists, Un Chien Andalou conformed to the idea, popular with Surrealists, of Freudian free-association.

Pop Art

Within British Pop Art, experiments with photomontage started as early as 1947 with Eduardo Paolozzi's BUNK! (1947-52), a series of 54 works composed of found or sourced photographs from American magazines. It was however Richard Hamilton's Just What Is It That Makes Today's Homes So Different, So Appealing? (1956), that introduced British Pop to the world. He too used images cut and pasted from American mass media publications and in so doing Hamilton offered an affectionate critique of post-war American consumer society.

The work of Paolozzi and Hamilton highlights the problem of how one classifies photomontage. In America, too, James Rosenquist, and Martha Rosler emerged as leading American Pop artists who experimented with a photomontage/collage technique. Rosenquist's President Elect (1960-61), for instance, combined images of President John F. Kennedy, a slice of cake, and an automobile while Rosler's works often connected found-images of middle-class housewives and interiors as an implicit feminist critique of contemporary American culture. Pop Art highlights the difficulty historians face when they attempt to categorize art generically since, sooner or later, one approach will organically overlap with another (photomontage and collage in this example).

Later Developments

By the 1970s photomontage was taken up by a number of prominent individuals. Artists, including Martha Rosler, Peter Kennard, Linder Sterling, and Barbara Kruger created composite works that gathered under the rubric of social protest and identity politics. Moving into the late-twentieth and early-twenty-first century, new photographic and digital technologies allowed for further innovations. These developments are evident in the conceptual digital photomontages of Andreas Gursky and Jeff Wall. David Hockney, meanwhile, developed photomontages out of Polaroid prints, calling them "joiners", while John Stezaker combined postcards with film stills.

The blended and juxtapositional constituents of photomontage have become time-honoured and omnipresent in the digital age. Many examples of digital photomontage are now designed to celebrate the imagination of the artist. The Spaniard Antonio Mora, for instance, uses images found on blogs and other online sources to create a "pure art" concerned with nothing more than visual effects and aesthetics. More recently, photomontage has become an essential element of multimedia installation, as seen for instance in Kruger's Belief + Doubt (2012) and Lorna Simpson's Unanswerable (2018).

Useful Resources on Photomontage

-

![Ovation TV | Heartfield]() 14k viewsOvation TV | Heartfield

14k viewsOvation TV | Heartfield -

![Zygosis: John Heartfield and the Political Image. 1 of 3]() 17k viewsZygosis: John Heartfield and the Political Image. 1 of 3

17k viewsZygosis: John Heartfield and the Political Image. 1 of 3 -

![Heartfield]() 14k viewsHeartfield

14k viewsHeartfield -

![Kurt Schwitters Documentary]() 64k viewsKurt Schwitters Documentary

64k viewsKurt Schwitters Documentary -

![David Hockney Joiners]() 0 viewsDavid Hockney JoinersSR Tafe Design Online

0 viewsDavid Hockney JoinersSR Tafe Design Online -

![David Hockney - Joiners - Documentary 2014]() 66k viewsDavid Hockney - Joiners - Documentary 2014

66k viewsDavid Hockney - Joiners - Documentary 2014 -

![What David Hockney's Brilliant Collages Reveal About Photos]() 23k viewsWhat David Hockney's Brilliant Collages Reveal About PhotosSmithsonian Channel

23k viewsWhat David Hockney's Brilliant Collages Reveal About PhotosSmithsonian Channel -

![Peter Kennard - Photomontage Today - 1982]() 503 viewsPeter Kennard - Photomontage Today - 1982

503 viewsPeter Kennard - Photomontage Today - 1982 -

![TateShots 14 April 2011]() 10k viewsTateShots 14 April 2011Peter Kennard: Studio Visit

10k viewsTateShots 14 April 2011Peter Kennard: Studio Visit -

![TateShots 21 March 2014]() 46k viewsTateShots 21 March 2014Lorna Simpson: Studio visit

46k viewsTateShots 21 March 2014Lorna Simpson: Studio visit

Ask The Art Story AI

Ask The Art Story AI