Summary of Renaissance Humanism

The art historian Jacob Burckhardt's The Civilization of the Renaissance in Italy (1860) first advanced the term Renaissance Humanism to define the philosophical thought that radically transformed the 15th and 16th centuries. Driven by the rediscovery of the humanities - the classical texts of antiquity - Renaissance Humanism emphasized "an education befitting a cultivated man," and saw the human individual "as the measure of the universe." Church leaders, scholars, and the ruling elite practiced and promoted the understanding of classical ethics, logic, and aesthetic principles and values, combined with an enthusiasm for science, experiential observation, geometry, and mathematics. Originating in Florence, a thriving center of urban commerce, and promoted by the Medici, the ruling family of the Italian city-state, the philosophy was connected to a vision in a new society, where the individual's relationship to God and divine principles, the world and the universe, was no longer exclusively defined by the Church.

Renaissance Humanism informed the works of groundbreaking artists, including Leonardo da Vinci, Michelangelo, Raphael, Botticelli, and Donatello, as well as architects like Brunelleschi, Alberti, Bramante, and Palladio. These artists exemplified the ideal of the "Renaissance man" as they excelled at various disciplines and pioneered new techniques and inventions, defined the artistic canon and were heralded as "masters" in their own right.

Key Ideas & Accomplishments

- Renaissance Humanism created new subject matter and new approaches for all the arts. Subsequently, painting, sculpture, the literary arts, cultural studies, social tracts, and philosophical studies referenced subjects and tropes taken from classical literature and mythology, and ultimately, Classical Art.

- Renaissance Humanism elevated the concepts of aesthetic beauty and geometric proportions historically provided by classical thinkers such as Vitruvius and given a foundation of ideal form and thought laid down by philosophers such as Plato and Socrates.

- The artists associated with Renaissance Humanism pioneered revolutionary artistic methods from one point linear perspective to trompe l'oeil to chiaroscuro to create illusionary space and new genres, including frontal portraiture, self-portraiture, and landscape.

- As historians Hugh Honour and John Fleming noted, Renaissance Humanism advanced "the new idea of self-reliance and civic virtue" among the common people, combined with a belief in the uniqueness, dignity, and value of human life. As historian Charles G. Nauert wrote, "this humanistic philosophy overthrew the social and economic restraints of feudal, pre-capitalist Europe, broke the power of the clergy, and discarded ethical restraints on politics...laid the foundations for the modern absolute, secular state and even for the remarkable growth of natural science."

- During this time, patronage dominated the art market as wealthy citizens took pride in promoting artists who created masterworks in a variety of fields from painting to science to architecture and city planning. This reflected the overall attitude of the importance of supporting the arts in a thriving society.

- Many of the concepts of Renaissance Humanism, from its emphasis on the individual to its concept of the genius, or Renaissance man, to the importance of education, the viability of the classics, and its spirit of exploration became foundational to Western culture.

Overview of Renaissance Humanism

“After seeing this no one need wish to look at any other sculpture or the work of any other artist,” Giorgio Vasari said of Michelangelo’s David. Michelangelo’s masterpiece exemplified the Renaissance practice of highlighting the grandeur and importance of mankind.

The Important Artists and Works of Renaissance Humanism

Dome of Cattedrale di Santa Maria del Fiore (Florence Cathedral)

This photograph depicts the iconic octagonal dome of Florence Cathedral dominating the skyline of the city. A marvel of innovative engineering and design, constructed of over four million bricks, the dome became a symbol of Renaissance Humanism, its soaring buoyancy evoking classical proportion and mathematical order. At the same time, the red brick linked the era's "rebirth" with the tradition of Florentine stonework and the red emblem of the Medici. Viewed as rivaling the Roman Pantheon (113-115), the dome exemplified a new era of humanist values, as historian Paulo Galluzi wrote; "It unites technology and aesthetics in an astonishingly elegant way. It symbolizes perfectly the union of science and of art."

When his design for the Florence Baptistery doors was rejected, Brunelleschi left Florence in disappointment and traveled to Rome. Wandering the city and countryside, accompanied by the young artist Donatello, he meticulously studied the design principles of Roman ruins and buildings and turned his energy toward architecture. His discoveries not only led to his design for the dome but the inventions that made constructing the structure possible, and his development of linear perspective - an idea that led the innovations of the time. The problem of creating a dome for Florence Cathedral was viewed as almost insoluble, until Brunelleschi radically created a new system of support by creating a dome within a dome. He also invented the horizontal crane and the mechanical hoist needed to lift and place the bricks in the herringbone pattern that made up an inverted arch.

His work exemplified the combination of artistic principles, informed by knowledge of classical design, with tireless scientific innovation. At the same time, often keeping his designs and ideas to himself for fear that his rival might appropriate them, he also operated with the belief in the unique knowledge of the inspired and cultivated artist, as he wrote "Let there be convened a council of experts and masters in mechanical art to deliberate what is needed to compose and construct these works." The dome and the design principles embodied in it became fundamental to subsequent architects.

Sandstone, marble, brick, iron, wood - Florence

Primavera

This famous Early Renaissance painting depicts figures from classical mythology: the god Mercury plucking a golden fruit from a tree, the three graces dancing together, and Venus, the goddess of love, at the center with Primavera, the goddess of spring, to her left.

The meaning of the mysterious scene, located within a woodland garden, has been much debated by scholars, as it has been viewed as an allegory, a depiction of various scenes from the writing of the Roman poet Ovid, or as a purely aesthetic arrangement. At the same time, some critics have deeply analyzed the work, finding its elements, including the hundreds of specific flowers naturalistically depicted, as reflective of Neoplatonic thought. Neoplatonism emphasized ideal love and absolute beauty as reflections of the ideal forms posited by the Greek philosopher Plato.

A sense of the hidden and sublime order of the world that, while pagan, was not inconsistent with Christianity, is shown in the artist's central figure, that simultaneously evokes Venus and the Virgin Mary. Botticelli's use of mythological subjects and his near nude female figures were groundbreaking. As art critic Jonathan Jones puts it, "Botticelli's Primavera was one of the first large-scale European paintings to tell a story that was not Christian, replacing the agony of Easter with a pagan rite. The very idea of art as a pleasure, and not a sermon, began in this meadow."

Botticelli was particularly influenced by Dante, the early Renaissance poet, whose platonic love for Beatrice informed his Divina Commedia (Divine Comedy) (1308-21), depicting his journey through Hell and Purgatory to Paradise. The artist drew illustrations and wrote commentary on the famous poet's work. Associated with the artistic and intellectual circles around Lorenzo de' Medici, the artist was influenced by Marsilio Ficino. Later in his career, as Florence was roiled by the rise of Savonarola, a priest who railed against pagan art and influences, Botticelli refuted his earlier subjects and began to focus on a series of illustrations depicting Dante's vision of the suffering souls in Hell and Purgatory. Though his art fell into relative obscurity, it was subsequently rediscovered in the 19th century and his paintings have become among the most recognizable artworks, reproduced in countless advertisements, brochures, and digital platforms.

Tempera on panel - The Uffizi Gallery, Florence

The Vitruvian Man

This drawing shows the ideally proportioned figure of a man in two superimposed positions, standing within a circle and square. Due to the superimposition of poses and geometric forms, the symmetrical and balanced figure evokes kinetic movement, while the drawing feels almost three-dimensional as if the viewer were looking into a volumetric geometric space.

Often called "The Canon of Proportions," and also known as "The proportions of the human body according to Vitruvius," the drawing and Leonardo's accompanying text reference the mathematical proportions of the Roman innovator. In the upper margin, Leonardo paraphrases from Book III of Vitruvius's De architectura, writing, "Vetruvio, architect, puts in his work on architecture that the measurements of man are in nature distributed in this manner." While in the lower text, Leonardo draws upon the architect's proportions but corrects them according to his own anatomical studies. Leonardo shared the architect's belief that the proportions of the human body were a kind of microcosm of the symmetry and order of the universe.

Other Renaissance artists drew the human figure according to Vitruvian proportions, but Leonardo innovatively drew upon his own study of human anatomy, as he realized that the center of the square had to be located at the groin rather than at the navel, as Vitruvius thought, and that the raised arms should be level with the top of the head. Combining scientific knowledge and mathematical study with the aesthetic principles of ideal proportion and beauty, the drawing exemplified Renaissance Humanism, seeing the individual as the center of the natural world, linking the earthly realm, symbolized by the square, to the divine circle, symbolizing oneness. Later artists have continued to draw upon the image for inspiration as seen in William Blake's Glad Day or The Dance of Albion (c.1794), and Nat Krate's Vitruvian Woman (1989).

Pen and ink on paper - Accademia, Venice

Self-Portrait with Fur-Trimmed Robe

In this three-quarters portrait, the artist, dressed in a nobleman's coat with fur trim, faces forward with his right hand raised as if in a gesture of blessing. This, along with his intense and serious expression, evoke traditional images of Christ Pantocrater, as if the artist were a living icon. Using chiaroscuro, his image is shadowed, merging into the dark background, while light highlights the right side of his face and body. The artist has signed the work twice, and prominently, with his initials and the year alongside the phrase, "Thus I, Albrecht Dürer from Nuremburg, painted myself with indelible colors at the age of 28 years" which floats in the inky background.

The groundbreaking work pioneered self-portraiture. Artists had been previously portrayed only as bystanders or secondary figures, often witnessing a scene. For example, Jan van Eyck's The Man with the Red Turban (1433) is thought to be a self-portrait but was presented as an anonymous individual. Dürer's image reflects the importance of the individual and the artist as an inspired genius, both concepts central to Renaissance Humanism.

Dürer travelled to Italy as a young man and was influenced by Renaissance Humanism and the leading artists or the era. He played an important role in the development of Northern Humanism, as he synthesized classical models with cultural beliefs and devotional practices in order to create a better society. His closest friend in Nuremberg was the classical scholar and translator Williblad Pircklheimer, a leading figure in the city's Humanist circles. Their intellectual discussions ranged from the writings of the Humanist Erasmus to the use of perspective in Italian painting to the meaning of Egyptian hieroglyphs.

In later life, Dürer's lifelong interest in geometry, proportion, and perspective was reflected in treatises including Four Books on Measurement (1525) and Four Books on Human Proportion (1528). As Jonathan Jones noted, the artist's "role model was Leonardo da Vinci... Dürer understood the sum of Leonardo's parts, at once craftsman, scientist and humanist intellectual. More than anyone else except Michelangelo, Dürer took up the challenge of the supreme Renaissance mind. And yet the sublime energies that Dürer's art channels are not those of a solitary mind but of an entire culture."

Mixed media on panel - Alte Pinakothek, Munich

David

This iconic statue was the first male nude carved in marble since the classical era. It depicts the Biblical hero David, as he turns to face the giant Goliath with a look of purposeful assessment, his raised left hand grasping his shepherd's sling and a stone cradled in his right. Over 17 feet tall, his muscular figure was seen as not only reviving the ideal male beauty represented in classical Greek sculpture but surpassing it. As Vasari wrote, "...this figure has put in the shade every other statue, ancient or modern, Greek or Roman." The work also exemplified a humanistic awareness of individual sensibility, as David is poised and yet with a touch of adolescent awkwardness. For the people of Florence, the figure of David represented the emerging primacy of the city-state as a "giant killer" among the European powers.

The artist employed a radical simplicity, as only the slingshot identifies the figure as David, and while the work evinces his mastery of anatomical knowledge, Michelangelo also deviated from the rules of proportion, making the right hand slightly larger than the left with his eyes looking in two slightly different directions. He did this because the work was created to stand at an elevated position on the base of Brunelleschi's dome of Florence Cathedral, and the sculptor seemed to have been aware that the work's full effect could be realized only by its relationship to the space around it, thus tweaking the anatomy in regards to the audience's viewpoint and unique perspective. As art historian Lois Fichner-Rathus noted, "No longer does the figure remain still in a Classical contrapposto stance, but rather extends into the surrounding space away from a vertical axis. This movement outward from a central core forces the viewer to take into account both the form and the space between and surrounding the forms - in order to appreciate the complete composition."

Marble - Gallery of the Academy of Florence, Florence

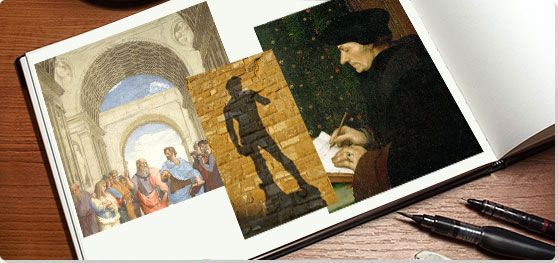

School of Athens

This famous fresco employs perspective to draw the viewer's eye into an animated scene where noted Greek philosophers, including Socrates, Pythagoras, Euclid, and Ptolemy converse or sit alone in a moment of reflection. At the center, beneath replicating classical arches, Plato in orange robes and Aristotle in blue walk side by side as they discuss philosophy and represent the Humanist view that art and science, beauty and logic, were mutually compatible endeavors. The books the two men carry - Plato's Timaeus and Aristotle's Nichomachaean Ethics - were fundamental texts to Renaissance Humanists. The painting creates a dynamic sense of philosophy, as thought is expressed in gestures, facial expressions, and intense conversations. The cynic philosopher Diogenes sprawls on the stairs, while in the lower center the philosopher Heraclitus seems to be writing or drawing. Some of the figures are believed to be contemporary portraits: Pico della Mirandola as a young man, Michelangelo as Heraclitus, and Leonardo da Vinci as Plato.

A statue of Apollo, the Greek god of music and art, is placed on the left, referencing Plato's philosophy of ideal forms, while Athena, the goddess of wisdom on the right, aligns with Aristotle's belief in empirical knowledge and logic. While the setting is classical with its arches and columns, the building is also designed as a Greek cross, influenced by the designs of the contemporary architect Bramante and representing the harmony between Christianity and the tenets of classical philosophy. This theme of harmony is reflected in the four frescos that Raphael painted for the study and library of Pope Julius II. The Disputation of the Holy Sacrament (1509-10) and The Cardinal Virtues (1511) depicted Christian subject matter, while The Parnassus (1509), showing the god Apollo, the muses, and noted classical and contemporary poets, along with The School of Athens, emphasized the classical world, reflecting both worlds united in the pursuit of wisdom.

Fresco - Vatican City

Self-Portrait as Bacchus or Sick Bacchus

This painting is thought to be a self-portrait of the artist as Bacchus, the Greek god of intoxication, fertility, and the theater, a figure of wildly creative and destructive energy. Here, dressed in Attic garb and wearing a garland of ivy, he twists to face the viewer, a bunch of white grapes clutched in his right hand, his head oddly turned as if suggesting he is in pain. Cast in a greenish light, the pallor of his skin, accentuated by his blue lips and dark shadowed eyes, evokes dissolution or illness. On the table in front of him, a bunch of purple grapes and two apricots, are naturalistically rendered, while at the same time evoking a phallic shape.

This was the first of a series of portraits, portraying a solitary young man in classical garb and emphasizing the hedonistic enjoyment of life. While drawing upon the classical subject matter of Renaissance Humanism, the work departed from that tradition in its naturalistic treatment of both the figure and its inclusion of still life. Here, some of the fruit on the table show signs of decay, and the figure, ill or, perhaps, drunk or hung over, is a radical departure from the Renaissance's idealized beauty and classical calm.

The art historian Roberto Longhi attributed the work to Caravaggio in 1913 and, at the same time, identified the figure as Bacchus, giving it its title. Previously, the work had been titled A Satyr, as garlands of ivy traditionally identified the licentious half-men, half-goat figures that haunted the forests of Greek myth, while Bacchus was usually depicted wearing a wreath of grape vine, though a bit of ivy was sometimes interwoven. Longhi also explained the figure's sickly pallor as due to the artist's discharge from the Hospital of the Consolazione after a severe bout of malaria. However, some scholars favor the explanation of Giulio Mancini, whose study of Caravaggio in Considerazioni sulla pittura (Thoughts on painting), written between 1617 and 1621, attributed the artist's hospitalization to severe injuries sustained by a kick from a horse. In essence, the work conveys a kind of mystery and ambiguity, as if alluding to other meanings outside the pictorial plane, in keeping with the development of individualism toward the idiosyncratic and the psychological in the Mannerist and Baroque periods.

Giovanni Baglione who wrote The Lives of Painters, Sculptors, Architects and Engravers, active from 1572-1642 (1642) said the artist used a convex mirror to paint the work and that it was originally a cabinet piece. The work was not commissioned, and it's thought that the young artist, in effect, painted it as a kind of advertisement of his skills in portraiture, classical subject matter, and still life, in order to attract patronage. But at the same time it may have announced his inclusion in the arcane scholarly circles associated with d'Arpino's studio where he then worked.

Oil on canvas - Galleria Borghese, Rome

Beginnings

The Discovery of Classical Texts

In Europe, as early as the 9th century, many classical texts were being "rediscovered" by society's leading thinkers who would contribute to the rise of Renaissance Humanism. Most notably studied was De architectura, the first century BC treatise by the Roman architect Vitruvius. Employing mathematical proportions for architecture, the human form, and all artistic design, Vitruvius developed what was called the "Vitruvian Triad," or virtues of unity, stability, and beauty. The text informed the Carolingian Renaissance and influenced a number of leading thinkers, including the theologian St. Thomas Aquinas, the scholar Albertus Magnus, and the poets Petrarch and Boccaccio. However, it had subsequently been overlooked until Poggio Barccioline, a Florentine humanist, found a copy in the Abbey of St. Gallen in Switzerland in 1414 and, subsequently promoted it to Florentine humanists and artists. It became foundational to the architects Brunelleschi, Leon Battista Alberti, Bramante, and Palladio, as well as the artist Leonardo da Vinci, and has become part of the artistic canon to the 21st century.

The 14th century poet Francesco Petrarca, known as Petrarch in English, has been dubbed both "the founder of Humanism," and "founder of the Renaissance." After discovering the letters of the Roman philosopher and statesman Cicero, he translated them, leading to their early and important influence among Italian intellectuals, scholars, and artists. He was also the first writer to compose his works in the vernacular rather than the traditional Latin.

Influenced by Vitruvius and a number of his contemporaries, the humanist Leon Battista Alberti became the primary theorist of architecture and art in the Early Renaissance. His three works, De Statua (On Sculpture) (1435), Della Pittura (On Painting) (1435), and De Re Aedificatoria (On Architecture) (1452) codified the concepts of proportion, the contrast of desegno, line or design, with colorito, coloring, and Brunelleschi's one-point perspective. A noted painter, poet, classicist, mathematician and architect, Alberti's books were the first contemporary classics of Renaissance Humanism. His writing also defined the ideal of the "universal man," as expressed in his motto, "A man can do all things if he will."

Platonism

With the introduction of Plato's work, Platonism and Neoplatonism became a primary force in Renaissance Humanism. The Byzantine scholar Gemistus Plethon introduced the works of the Greek philosopher Plato at the 1438-39 Council of Florence and influenced Cosimo de' Medici, the head of the ruling Florentine family, who attended his lectures. Marsilio Ficino, an Italian scholar and priest, was also influenced by Plethon, dubbing him "the second Plato," and, subsequently with Cosimo's support, began translating all of Plato's work into Latin for the first time, which he published in 1484. As art historian James Hankins wrote, "Ficino's Platonic revival was among the most original and characteristic of Quattrocentro philosophy," and his influence grew to extend far beyond Florence. As a result, Renaissance Humanism emphasized aesthetic beauty and geometric proportions, derived from Plato's ideal forms.

Traditionally, it has been thought that, following the Council of Florence, Cosimo de' Medici sponsored what was called the Platonic Academy (also known as the Neoplatonic Florentine Academy), meant as revival of Plato's Academy led by Ficino. Other members of the group included Gentile de'Becchi, Poliziano, Cristoforo Landino, and Pico della Mirandola. However, contemporary scholarship has begun to refute this, finding it a legend, based upon a mistranslation of Ficino's writing and developed in later 16th century works promoting the reputation of the Medici. In any case, Florence was the dynamic hub of Renaissance Humanism, as new works from the group appeared. Pico della Mirandola's Oration on the Dignity of Man (1486) has been called the "Manifesto of the Renaissance," as he emphasized the dignity and value of individual human life for its own sake, independent of religious thought.

The Italian City State

The development of Renaissance Humanism was profoundly connected to the rise of the urban middle class in the Italian city-state, as shown in Florence's dubbing itself, "The New Athens." The Florentine republic, ruled by the merchant class rather than a hereditary monarch, saw itself as akin to the classical republics of Greece and Rome. The Medici family, who became the de facto and sometimes official rulers of Florence for the next two centuries, derived their great wealth from the textile trade and the local wool industry, but much of their influence throughout Italy and later Europe was based upon banking. In 1377 Giovanni di Bicci de Medici had founded the Medici Bank, the first "modern" bank, and various political alliances were formed in the following centuries, bankrolling noble families throughout Europe. Though Giovanni's son Cosimo never held an official office, in power and influence, he was, in effect, the ruler of the city. His view of his role was essentially humanistic, emphasizing knowledge, an aesthetic sense, and individualism, combined with civic power and pragmatic wealth. A noted collector of classical texts and patron of the scholars who studied and translated them, he was also the leading patron of the arts, and, believing in the power of a humanistic education, established the first public library. Private patronage, evincing a belief not only in the unique genius of an artist but of the exceptional knowledge and taste that commissioned the work, became a dominant factor. At the same time, as historians Hugh Honour and John Fleming noted, Renaissance Humanism introduced "the new idea of self-reliance and civic virtue - civic and mundane," which involved the populace on every level rather than the medieval models of contemplative religious life or chivalric knights and kings.

High Renaissance

The term, High Renaissance, coined in the early 19th century, to denote the artistic pinnacle of the Renaissance, referred to the period from 1490-1527, defined by the works of Leonardo da Vinci, Michelangelo di Lodovico Buonarroti Simoni (known as Michelangelo), Raffaello Sanzio da Urbino (known as Raphael), and Donato Bramante. Humanism fueled the era's artistic achievement, as Pope Julius II envisioned Vatican City as the cultural center of Europe, reflecting the glories of Christendom and rivaling the splendor of ancient Rome. A leading art patron, he commissioned Raphael to paint religious and classical frescoes in his papal residence and Michelangelo to paint the Sistine Chapel, combining biblical scenes with figures taken from Greek mythology.

The widespread humanist belief in the ideal of the Renaissance man, and the artist as a genius, meant that the leading artists created masterworks in a number of fields, from painting to architecture to scientific invention to city planning. Michelangelo was profoundly influenced by the discovery of the classical sculpture Laocoon (c. 42-20 BC), an excavation he supervised under the Pope's patronage.

Northern European Renaissance

In Northern Europe, while influenced by the Italians, Renaissance Humanism was primarily connected with the works of the Dutch Desiderius Erasmus and the German Conrad Celtis. A Catholic priest, Erasmus was called "the Prince of the Humanists," and his wide ranging work included new translations from Greek and Latin of The New Testament (1516), In Praise of Folly (1511) a satirical look at religion, and Adagia (1508) a collection of Latin and Greek proverbs. He argued for what he called "the middle way," a path bridging knowledge and faith, as well as Christianity and Humanism. Northern European Humanists had a great influence upon the development of the Protestant Reformation, as the emphasis on a person's pursuit of knowledge, reason, and a study of the liberal arts, extended into religion, developing a focus on the individual's relationship with God, rather than a mediating church. As a result less emphasis was given to classical texts and to classical subject matter, and the focus was often on ethics, the individual in society and community, and observation of the natural world and ordinary human life. Portraiture and self-portraiture, landscape painting, and genre scenes or elements, became distinguishing features of Northern European Renaissance art that was led by the likes of Albrecht Dürer and Jan van Eyck.

Concepts and Trends

Renaissance Man

The concept of the Renaissance Man was first advanced by the architect Leon Battista Alberti as he wrote of the Uomo Universale, or Universal Man, reflecting his belief that "a man can do all things if he will." The ancient Greeks, many of whom were polymaths excelling in philosophy, mathematics, engineering, and art, were seen as role models. Alberti himself exemplified the concept as he was also a leading poet, mathematician, scientist, classicist, cryptographer, and linguist and known for his physical prowess and skill as a horseman. As the critic James Beck wrote, "to single out one of Leon Battista's 'fields' over others as somehow functionally independent and self-sufficient is of no help at all to any effort to characterize Alberti's extensive explorations in the fine arts."

Many of the Renaissance's leading artists excelled in a number of fields, as seen by Michelangelo's work in sculpture, painting, architecture, and poetry, or Brunelleschi's architectural designs. Informed by his knowledge of mathematics, perspective, and engineering, Leonardo da Vinci became legendary as the model of the Renaissance Man. His discoveries crossed the fields of science, music, anatomy, geology, astronomy, botany, paleontology, and cartography, being surpassed only by his artistic achievements. As art historian Helen Gardner wrote, "his mind and personality seem to us superhuman, while the man himself mysterious and remote." When Giorgio Vasari published his The Lives of the Most Excellent Painters, Sculptors, and Architects (1550), the ideal was further established and forever linked to the concept of the artist as an almost divinely inspired genius. Rather than skilled craftsmen, artists were seen as having an innate and exceptional gift that, driven by tireless curiosity and an inexhaustible creative imagination, could conquer any task.

At the same time, another effect was a valuing of the individual, irrespective of class or wealth, as the gift of genius could strike anywhere. The English Renaissance poet and playwright Shakespeare expressed this sentiment perfectly in Hamlet (1603): "What a piece of work is man, How noble in reason, how infinite in faculty, In form and moving how express and admirable, In action how like an Angel, In apprehension how like a god, The beauty of the world, The paragon of animals."

Classicism

As the historian Paul Oscar Kristeller wrote, Humanists saw the classical legacy as "the common standard and model by which to guide all cultural activity." As the philosophy took hold, an emphasis on education in the humanities and the liberal arts spread throughout society. The word humanism originated in the Italian phrase, studia humanitatis, or study of human endeavors, introduced by Leonardo Bruni who wrote History of the Florentine People (1442), considered the first modern history book. He divided history into three periods: Antiquity, Middle Age, and Modern, and saw the Middle Age as a dark age, even though that era was defined and dominated by the Christian church. Humanism, combined with a study of classical texts, became a secularizing influence, developing a new curriculum that saw the modern age as awakening from a dark age to the light of antiquity.

Scientific Inquiry

The dialogues of Plato introduced humanists to Socrates, who was famously reported to have said that he was the wisest of men only because he knew nothing. His philosophical method emphasized inquiry and challenging assumed knowledge with an ardent round of questioning. As a result, Humanism valued skepticism, enquiry, and scientific exploration, countering its other impulse toward reverence of antiquity. As a result, observation of natural phenomena and experimentation drove the humanists: for example artists including da Vinci and Michelangelo studied human anatomy, engaging in autopsies on corpses, even though forbidden by the Catholic church. Art and science became equally important and often codependent endeavors.

Later Developments

Many of the concepts of Renaissance Humanism, from its emphasis on the individual to its concept of the genius, the importance of education, the viability of the classics, and its simultaneous pursuit of art and science became foundational to Western culture. As a result, subsequent artistic eras often defined themselves in comparison or in reaction to the principles, subject matter, and aesthetic values and concepts of Humanism.

Mannerist painting, reacting against Renaissance Humanism's classical ideals of proportion and illusionistic space, created disproportionate figures in flat often-crowded settings with uncertain perspective. In contrast, the art of the Baroque period returned to classical principles of figuration and perspective, while emphasizing naturalistic rather than idealized treatments. Yet, both Mannerism and Baroque eras built upon the mythological subject matter of Humanism, though further secularizing it, and took individualism as a tenet that drove the movement toward the psychological and the idiosyncratic.

This back and forth continued in subsequent eras, as the Rococo period, known for its light-hearted and pastel depictions of the individual in aristocratic life or in genres focused on ordinary people was followed by the Neoclassical period, which, once again, emphasized the classical principles and heroic subject matter of ancient Rome. Nevertheless, the concepts of Renaissance Humanism continued to be foundational and were subsequently developed, as the spirit of experimentation, inquiry, and discovery fueled the Enlightenment, also known as the Age of Reason. Individualism developed into the feeling and imagination of the Romantic era, and, combined with the concept of the republic and civic virtue and public education, informed American independence and the French Revolution.

As historians Hugh Honour and John Fleming noted, Renaissance Humanism advanced "the new idea of self-reliance and civic virtue" among the common people, combined with a belief in the uniqueness, dignity, and value of human life. As historian Charles G. Nauert wrote, "this humanistic philosophy overthrew the social and economic restraints of feudal, pre-capitalist Europe, broke the power of the clergy, and discarded ethical restraints on politics...laid the foundations for the modern absolute, secular state and even for the remarkable growth of natural science."

Artists like Michelangelo, da Vinci, Botticelli, and architects like Brunelleschi, Alberti, and Palladio, were viewed as masters informing subsequent generations of artists, whether reinterpreting their works or challenging them. For instance, Salvador Dalí revisited both Albrecht Dürer's iconic Rhinoceros print and da Vinci's Last Supper in Surrealist configurations. Cindy Sherman photographed herself in the pose of Caravaggio's Sick Bacchus, while Nat Krate has reconfigured da Vinci's work in her Vitruvian Woman (1989).

Ask The Art Story AI

Ask The Art Story AI