Summary of The Society of the Spectacle

The idea "Society of the Spectacle" sums up much of the revolutionary spirit of the 1960s artistic avant-garde. Outlined in the writing of Guy Debord, the idea is based on Marxist concepts, in particular the idea that Capitalist society has reduced reality to a play of illusions; that the logic of money and economics has imposed itself onto human relations so thoroughly that our sense of reality can no longer be trusted. The idea of the Society of the Spectacle led to a creative spirit within modern art that was obsessed with the idea of shattering illusion: from confrontational performance artworks to psycho-geographical walks, many artists became fundamentally concerned with breaking apart and redefining our sense of reality. This had a profound influence on the move from object- to idea- of Performance-based art to the Conceptualism of the 1960s and beyond.

Key Ideas & Accomplishments

- Although Guy Debord was the architect of the idea, the concept of "The Society of the Spectacle" was thoroughly rooted in Marxist theory. Debord was influenced in particular by Marx's assertion that, in a society based on the exchange of objects for money, we are unable to experience each other as truly human. We begin to place more value on objects than people, and thus lose some vital component of our sense of reality; reality becomes in some sense 'fake' or illusory.

- The idea of the Society of the Spectacle emerged in Paris in the 1950s-60s, via a number of avant-garde groups that brought together critical theory, poetry, avant-garde art, and film-making. The most significant of these was the Situationist International, founded by Debord in 1957. The idea of the Society of the Spectacle was thus both a product of the political atmosphere of post-war Paris and one of the catalysts for the wave of revolt that swept across the city in 1968.

- The idea of the Society of the Spectacle had a profound effect on the development of postmodern art, by leading artists away from object-making and towards Performance art, Conceptual art, and other forms of "dematerialized" art. Feeling that the conventional experience of art had become coopted by the play of spectacle, many artists turned to forms of experiential or idea-based art which denied the viewer the satisfaction of a material object.

The Important Artists and Works of The Society of the Spectacle

Broadway by Light

Jewish-American photographer and filmmaker William Klein's first film (which he also considered "the first pop film"), Broadway by Light, is a twelve-minute experimental, documentary short which pairs high-contrast video of the bright lights and flashing advertisements of New York's Times Square with jarring, frenetic, and ominous music. The film conveys a nightmarish sentiment that mirrors Debord's sense of the Society of the Spectacle. Although the video images on their own may appear unremarkable, or perhaps even thrilling, behind the glitz and glamor lies something sinister and alien.

Broadway by Light was Klein's first significant step toward using the camera to critique social and cultural norms. Film critic and curator Ed Halter writes that "[t]he nature of such persuasive images, created for marketing and propaganda, would become a major theme of Klein's cinematic output." Klein, who had studied under French artist Fernand Léger and worked as a photojournalist for publications such as Vogue, was partly looking askance at his own commercial career with Broadway by Light. He later put that career on the line with his first feature film, Who Are You, Polly Magoo? (1966), a critique of the vapid Parisian fashion scene. Vogue fired him shortly after the film's release. In 1969, Klein's second fictional film, Mr. Freedom, continued in the vein of anti-capitalist critique, with the titular character personifying the United States, Halter notes, in the form of "a racist global policeman, in thrall to American corporate interests."

Hatler states that "Mr. Freedom and Broadway by Light both attempt to turn the power of spectacle back upon itself to create a radical counter-image," summing up the connection between Klein's work and the idea of the Society of the Spectacle. Klein himself alluded to the same idea in an interview looking back on the period when he made Broadway by Light. "I did this book on New York [before Broadway by Light]: black-and-white, grungy photographs. People said, 'What a put-down - New York is not like that. New York is a million things, and you just see the seamy side.' So I thought I would do a film showing how seamy New York was, but intellectually, by doing a thing on electric-light signs. How beautiful they are, and what an obsessive, brainwashing message they carry. And everybody is so thankful for this super spectacle."

Film

L'Avant-Garde Se Rend Pas (The Avant-Garde Does Not Surrender)

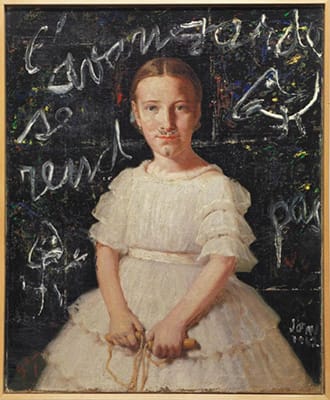

Asger Jorn's 1962 work L'Avant-Garde Se Rend Pas is a disfigured, found portrait of an affluent young girl in a ruffled white frock. Jorn scribbled the titular text in the background of the image, also adding a crudely drawn bird and stick figure. In homage to Duchamp's doctored Mona Lisas, he also used black paint to add a mustache and goatee-style beard to the girl's face. As Karen Kurczynski writes, "Jorn lampoons the bourgeois propriety of the girl by vandalizing her portrait. He accomplishes this both through the facial additions and the vulgarity of the graffiti text, applied in the high-art medium of oil paint, appearing behind the girl as if out of the repressed unconscious of the history of painting."

In their quest to find ways of challenging the Society of the Spectacle, the Situationist International (SI) of which Dutch painter Jorn was a member, developed artistic techniques such as détournement (French for "rerouting, hijacking"). This was defined in the SI's inaugural 1958 journal as "[t]he integration of present or past artistic productions into a superior construction of a milieu." Kurczynski describes détournement as "an explicitly political practice, intended to devalue the discourse or institution it attacked." Artworks employing techniques of détournement often manifest as satire or pranks, which seek, as Douglas B. Holt writes, to turn "expressions of the capitalist system and its media culture against itself."

Jorn, who was also a founding member of CoBrA, was the SI artist who employed détournement most consistently in his work, as in his Modifications (1959) and New Disfigurations (1962) series - the above image is from the latter series. In these sets of works, as Kurczynski explains, "Jorn added grotesque imagery or abstract painted or dripped additions to amateur academic-style paintings found in flea markets." Works similar to Jorn's were made around the same time by Enrico Baj and Daniel Spoerri, neither of whom were part of the SI. As Kurczynski notes, the "primary significance" of such works "lies not only in their challenge to the dominant discourses of art in the late 1950s, but also in their potential as exemplary tactics to trigger new and more sophisticated actions against the institutional discourse of art today, with its continuing tendency to reify itself." The détournement tactic was later adopted by the Punk subculture, "culture jammers." and graffiti and street artists, among others.

Oil on found canvas - Centre Pompidou, Paris

Marilyn Diptych

Pop artist Andy Warhol's Marilyn Diptych, created shortly after the actress's death by drug overdose in April 1962, connected to the idea of the Society of the Spectacle. The piece consists of two grids - on separate canvases - made up of repeated images of Monroe's face. To the left she appears heavily pigmented in bright colors, with yellow hair, pink face, and blue top. To the right her image is in grainy black and white. This was intended to represent the contrast between her public image and her private life. The image of Monroe's face is, in many instances, blurred and distorted, a result of flaws in the silkscreen printing process used to make the work. As curator Tina Rivers Ryan points out, Warhol also increased the contrast of the photographic image thus "flattening" its appearance, alluding to the shallow nature of the star's social character.

Warhol once famously stated that he was only interested "in the surface of things." As culture writer Anna Pritchard notes, he "was drawn to the mass subject. He understood its seductive power and employed its resonance in his art. [...] Warhol took public images, icons and motifs from commercial culture as his palette and opened the outside world to appropriation and transformation. His paintings, which mimic the forms and channels of mass culture, testify to the enormous and unavoidable power of the commodity fetish in a world of constant visual stimuli and product overload." He producing huge runs of screen-printed images of celebrities. Other public figures portrayed in the same manner as Monroe include former First Lady Jackie Kennedy, actresses Liz Taylor and Grace Kelly, and Chinese communist leader Mao Zedong.

Marilyn Diptych is partly relevant to the idea of the Society of the Spectacle in its engagement with celebrity, a topic Debord explored in detail in The Society of the Spectacle. He described film-stars as "spectacular representations of living human beings [....] As specialists of apparent life, stars serve as superficial objects that people can identify with in order to compensate for the fragmented productive specializations that they actually live." In other words, stars - at least in public perception - are commodities that people became attached to as avatars of the illusory life capitalism encourages them to strive for. With its diptych form, the above work even suggests - as per Marxist theory - that the adulation of the commodity (in this case a celebrity) might take on the character of religious worship, by mimicking the diptych form used in church altarpieces.

Warhol's use of mass-production methods such as silkscreen printing to produce large runs of his works, often deliberately sacrificing technical quality in the process, is also highly relevant to ideas found in The Society of the Spectacle. As Debord wrote, "[t]he loss of quality that is so evident at every level of spectacular language, from the objects it glorifies to the behavior it regulates, stems from the basic nature of a production system that shuns reality. The commodity form reduces everything to quantitative equivalence." That is, the pervasiveness of spectacle means that the individual qualities of objects in and of themselves can be ignored once they become commodities.

Silkscreen ink and acrylic paint on 2 canvases - The Tate, London

Untitled Film Still #56

The photographs of Cindy Sherman offer profound insights into how the Society of the Spectacle impacts upon individual identity. In her Untitled Film Still series, for example (1977-80), we seem to grasp the truth of Debord's assertion that, in contemporary consumer society, "everything that was directly lived has receded into a representation." For this series Sherman photographed herself made up and costumed to look like various female archetypes, such as the housewife, the femme fatale, the 'city girl,' the 'vamp,' the jilted lover, and the vulnerable naif. Sherman's description of these images as "film stills" referenced the openly fictional quality of the "identities" assumed. They are not naturally-occurring so much as 'identity categories' that have come to define femininity through mass culture, including Hollywood cinema.

As a child growing up in Long Island, photographer Sherman loved Hollywood B-movies and television sitcoms. She says, "I remember, as a child, being drawn to shows like I Love Lucy, but, even then, realizing the artifice in them, the goofy sentiment of all those perfect mums with the perfect homes and perfect men. Growing up in the actual suburbs made me look at what was being portrayed and realize that it was fake. So I was both attracted and repulsed by those films and shows." This obsession with artifice comes across in the film-still series, as writer Sean O'Hagan notes. "The generic female characters [Sherman] inhabits - furtive film actresses, harassed looking housewives, prim librarians - are ambiguous creations, identifiable as archetypes of femininity but also marooned from their contexts, freeze-framed in some bigger, more mysterious narrative. They are photography as elaborate performance: cerebral, ironic, deadpan....they are pure persona." At the same time, the possibility of escaping the artifice is never entirely abandoned in this series. For instance, in many of the photographs, wigs are visibly slipping off Sherman's head, or her makeup is poorly blended, as if to allude to alternative reality beneath.

While each single Sherman photograph is interesting, it is when her entire body of work is considered as a whole that we are able to understand its value as cultural critique, an attack on the Society of the Spectacle. In much the same way, a single object or image produced within the Society of the Spectacle will read as innocuous. It is only in appreciating the vast quantity of images and objects that inundate us on a daily basis that we are able to comprehend their collective impact.

Gelatin silver print - Art Institute of Chicago

New Shelton Wet/Dry Doubledecker

The notorious artist Jeff Koons frequently appropriates or recreates consumer goods in the dominant visual vocabulary of the Society of the Spectacle in his work. New Shelton Wet/Dry Doubledecker was produced at the beginning of the 1980s, "the era of conspicuous consumption," as curator Nancy Spector notes, and also the time when Koons was working on Wall Street selling stocks and mutual funds for First Investors Corporation and Smith-Barney. In fact, it was with the money he earned at these jobs that he funded his first series, The New, of which New Shelton Wet/Dry Doubledecker was part. Spector explains that "these sculptures sufficed as a conceptual portal into Koons's wholehearted embrace of mass-produced objects, his 'fascination with things' for which Duchamp's "readymades" gave art-historical permission. The commodities that Koons plucked out of their utilitarian roles for this generative series were never-been-used, right-off-the-shelf, top-of-the-line vacuum cleaners [...] These industrially produced appliances are encased within exquisitely crafted, clear acrylic cases that ironically seal out the dust and grime they are designed to capture. Their encasement renders these items essentially inoperable."

By showcasing these objects in this way, and by illuminating them in their cases with cold, sterile, florescent lights, Koons elevates these commodities, intended as household appliances, to the status of "high art." Says Spector, "In Koons's commodified universe, we are invited to contemplate the preconceived antidote to Capitalism's calculated obsolescence - the most recent, just off the assembly line, brand-spanking-new item. His placement of the sculptures and accompanying signage in the museum's large, store-front windows, the quintessential presentation mechanism for consumer goods, doubled the reference to the mercantile dimension." Curator Scott Rothkopf notes an additional similarly between Koons's vacuum cleaners and the readymades of Dada artist Marcel Duchamp, asserting that "As with Duchamp's urinal [Fountain (1917)], these products have clear anthropomorphic and sexual associations, with pliant trunks, sucking orifices, and bags that inflate and deflate like lungs."

Koons has made it clear that he wants his works to remain open to myriad interpretations, though one particularly interesting potential reading of his vacuum cleaner works relates to their appearance, as he puts it, as "family units" (for instance, with New Shelton Wet/Dry Doubledecker looking like "identical twins", and other works in the New series looking as though the vacuum cleaners are "mama bear, papa bear, and baby bear"). In this interpretation, one could understand these works as referencing the way in which the post-war North-American family defines itself through the commodities it possesses, just as the identity of the individuals in the Society of the Spectacle is reduced to the representation of the objects and images they accumulate.

Vacuum cleaners, plexiglass, and fluorescent lights - MoMA, New York

Paradox of Praxis I (Sometimes Making Something Leads to Nothing)

The origins of Conceptual art can be dated back to the 1960s, when artists began to explore the possibility that art could exist simply as an idea, or network of ideas, rather than as a physical, visible object. This can be related to the Situationists' attempt to bypass the play of spectacle which they felt had saturated the conventional art world, and to remove their art from capitalist exchange processes. The American Conceptual artist Lawrence Weiner talked about people "keep[ing] [his] art in their heads", stating "they don't have to buy it to have it - they can just have it by knowing it." Similarly, American Conceptual and Minimalist artist Sol Lewitt asserted that "[i]deas alone can be works of art; they are in a chain of development that may eventually find some form. All ideas need not be made physical."

The Belgian-born, Mexico-based artist Francis Alÿs has embraced the conceptual and rejected the material in his art since the 1990s. In Paradox of Praxis I (Sometimes Making Something Leads to Nothing), he pushed a block of ice around the streets of Mexico City for about nine hours until it melted away. The only physical records of the work are photographs and videos. Art historian James W. Yood writes: "[t]he video of that project has a kind of quixotic absurdity that is very compelling, juggling as it does the earnestness of that cumbersome task, a recognition of the importance of ice for street vendors in a tropic clime such as Mexico, and Alÿs's making of an absence in the end - all of which invited a range of poetic interpretations that can be both disorienting and liberating." A similar approach characterizes Alÿs's subsequent works, such as Fairy Tales (1995), which involved walking around in a gradually-unravelling sweater, leaving behind a long wool yarn. In 2002, he performed the work When Faith Moves Mountains in Lima, Peru, for which some 500 local volunteers used hand-held shovels to move a sand dune from one spot to another.

Another Conceptual artist whose work rejects the commodity status of art, and seeks to operate outside the Society of the Spectacle, is the Mexican Gabriel Orozco. He has stated that he aims to "disappoint the viewer" with his art. To that end he has created pieces such as Empty Shoe Box (1993), which involved placing an empty shoe-box on the floor as a contribution to the Venice Biennale. Art historian Benjamin Buchloh writes of this work: "[t]he reasons for the quietly compelling attraction of an utterly banal object are of course manifold, yet one primary explanation could be found in the fact that the presentation of an empty container, rather than the object itself, traces the very shift from use value to exhibition value that has occurred in the culture at large." Says Orozco, "[t]he emphasis is not on the materials, but on the idea that is expressed through them."

Performance - Mexico City

Flower Ball

Japanese artist Takashi Murakami creates works that blend high and low culture, frequently employing the Japanese Kawaii (cute) aesthetic to explore the impact of Western consumer culture on contemporary East-Asian audiences. While he is often accused of being a "sell-out," Murakami's brightly-colored, easily palatable pop imagery is partly intended to critique the use of spectacle in contemporary consumer culture to mask the traumas of collective psychological experience. For instance, his recurrent "smiling flowers" motif, as in the above image, represents the "suppressed, paradoxical sentiments" felt by Japanese citizens traumatized by the Hiroshima and Nagasaki bombings of 1945.

Murakami has also described his art as simply expressing his lived reality, which has been mediated by a particular, Japanese variant of popular culture and consumerist spectacle since his childhood. Says Murakami, "Japanese people of my generation grew up reading manga and watching anime and special effect films, so these things are thickly in our flesh and blood. We can't help expressing them. Those who are younger than me must have had different influences from ever-developing sources of entertainment, such as game, YouTube, social media, or VR, so I'm sure their ways of creative expression would be different than mine. In any case, the important thing in art is how you express your reality; it's crucial to accurately depict the influences you have received in life through various methods and grammars of art".

Similar to Andy Warhol, Murakami produces his artworks in a factory-like workshop, with a large team of assistants who not only make, but also market and sell, his pieces. One is never able to say for certain what degree of involvement, if any, Murakami has had with a particular work - much as commodities emerge from manufacturing process that alienates the consumer from the laborers. At the same time, like Warhol, Murakami has been happy to participate in, and benefit financially from, the Society of the Spectacle that his work purportedly critiques. As the artist once stated, "[i]n Japan, a gallery has no meaning, and a Louis Vuitton shop is a more powerful place to see something." He frequently collaborates with big-name fashion brands and celebrities. For example, his smiling flower motifs have appeared on album covers and merchandise for musical performers such as Kanye West, J. Balvin, Drake, and Kid Cudi, as well as products created in collaboration with Louis Vuitton, Vogue, Perrier, COMME des GARÇONS, Crocs, and Supreme.

Acrylic on canvas - Seattle Art Museum

Coca-Cola Ad

This print by Banksy - an anonymous British street artist - critiques advertising culture and calls for consumers to rebel against the brands that manipulate their emotions while contributing to the unequal division of wealth in the world. It can be seen as an example of "culture jamming," a contemporary upgrade on the techniques of Situationism. Culture jamming aims to highlight and challenge various tenets of the Society of the Spectacle, such as commodity fetishism, conspicuous consumption, and loss of individuality. According to media scholars Moritz Fink and Marilyn DeLaure, culture jamming refers to a "collection of tactics, as well as a critical attitude and participatory, creative form of activism."

The term "culture jamming" references "radio jamming," an activity to which the Situationist International compared their activities in 1968. Often, culture jammers use "memes" (instantly recognisable images/motifs) like corporate advertising campaigns or logos, and subtly alter them to present a message that differs from the original. For instance, a culture jammer might reproduce the style of a Nike marketing campaign for the purposes of calling attention to the sweatshop labor used by the company. The goal of culture jamming, as cultural critic Umberto Eco asserts, is to "restore a critical dimension to passive reception." This often occurs through forcing the viewer to do a double-take, presenting them with an image that may, at first glance, appear mundane, but which contains content that draws them in for a closer look.

Banksy often engages in culture jamming, using détournement and related tactics - including the use of graffiti as an art-form - to draw attention to the negative effects of mass media and advertising. In the above image, Banksy adopts the aesthetics of typical Coke advert while urging viewers to become more educated on the ways large corporations control their lives. The text ends with a call to action, inviting consumers to appropriate and subvert advertising imagery without worrying about copyright law. Banksy's text can be seen as a contemporary Situationist gesture, an attempt to shake the viewer out of the illusions generated by the Society of the Spectacle, and to take their life into their own hands.

Digital image - Online

Beginnings

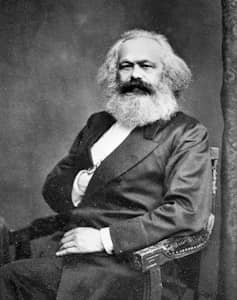

Karl Marx

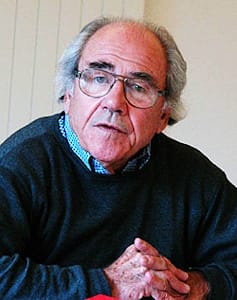

The phrase "The Society of the Spectacle" was coined by the French filmmaker and theorist Guy Debord (1931-94), and is associated in particular with his 1967 essay of the same name. But Debord's concept of "the spectacle" is strongly rooted in the earlier theories of German political philosopher Karl Marx, author of The Communist Manifesto (1848). The Marxist concepts of commodity fetishism, alienation, and reification are particularly central to Debord's ideas. Broadly speaking, Marx was concerned with the ways in which capitalist modes of production result in class conflict between the ruling and working classes.

By "commodity fetishism", Marx was referring to the apparently "mystical quality" certain objects accrue for us, the "metaphysical subtleties and theological niceties" we associate with those objects when we prioritize their "exchange value" over their "use value." "Exchange value" refers both to the monetary cost of an object and the aura that the object accrues based on its cost. Objects described in terms of their exchange value are often called "commodities." Unlike use value, exchange value is not related to the physical function or properties of the object. Nor does exchange value reflect the details of the labor involved in producing an object: for example, who made it, how long the process took, and how the person or people who made the object were treated.

In modern capitalist society, according to Marx, we come to worship certain inanimate objects because of their exchange value. Without realizing it we imbue these objects with supernatural powers and come to "fetishize" them (develop an intense, irrational emotional attachment to them), almost as if they were religious idols. For example, two pairs of sneakers may be physically similar, composed of nearly identical materials and component parts, and have the same use value. However, the addition of a prestigious brand-name label, like Nike or Adidas, to one pair, increases its value, due to the perceived social value of that brand name.

At the same time, we as consumers are prevented from seeing or knowing about the people and processes involved in the object's production, including any exploitative practices. This brings us on to the idea of "alienation." According to Marx, capitalism results in the alienation of consumers from producers: the one cannot see the conditions in which the other toils. Perhaps more importantly, capitalism - particularly the factory-line capitalism that became prominent during Marx's lifetime - also prevents workers at different points of the production process from knowing what the rest are doing. And it prevents them from developing an emotional relationship with the thing they are making: what is sometimes called 'the alienation of the worker from the product.' The inability of workers to develop emotional and conceptual relationships with the people they work alongside and the things they make marks a key distinction, in Marxist terms, between industrial capitalism and the cottage industries and agrarian economies that preceded it.

Commodity fetishism and alienation are connected in turn with the Marxist concept of "reification". In Marxist terms, to reify something means to turn a subject (such as a person) into an object. More specifically, it means the way that people are dehumanized through interaction which prioritises the exchange of capital and commodities. Thus, a person is seen simply in terms of their relevance - their value or impediment - to that exchange, to the acquisition of money or commodities, rather than as a human being. Economist and sociologist Val Burris explains reification as "a situation of isolated individual producers whose relation to one another is indirect and realized only through the mediation of things (the circulation of commodities), such that the social character of each producer's labor becomes obscured and human relationships are veiled behind the relations among things and apprehended as relations among things."

Importantly, reification also means that the economic and social conditions in which an object was created come to acquire the same quality of 'thingness,' of naturalness and inevitability, that the object itself possesses. This prevents the possibility of thinking about alternative ways of organizing human relationships: political and social progress, in other words. As Burris puts it, "a particular (historical) set of social relations comes to be identified with the natural properties of physical objects, thereby acquiring an appearance of naturalness or inevitability - a fact which contributes, in turn, to the reproduction of existing social relations". Political strategist Margherita Giannella notes that, "[t]hrough reification, human beings become dominated by things and become more thing-like themselves".

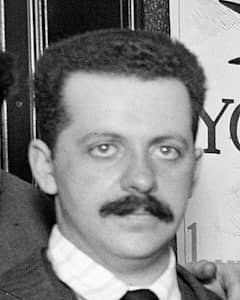

Edward Bernays

Edward Bernays was an Austrian-American public relations theorist and the author of Propaganda (1928). He revolutionized the fields of advertising and marketing, pioneering strategies for using people's subconscious desires (for instance, their desire for power, admiration or adoration) to convince, manipulate, or 'brainwash' the general public into consuming in particular ways. His strategies drew significantly upon psychological theories, particularly from the field of psychoanalysis, developed by his uncle, Sigmund Freud.

In Propaganda (1928), Bernays wrote that "[t]he conscious and intelligent manipulation of the organized habits and opinions of the masses is an important element in democratic society. Those who manipulate this unseen mechanism of society constitute an invisible government which is the true ruling power of our country. [...] We are governed, our minds are molded, our tastes formed, our ideas suggested, largely by men we have never heard of. This is a logical result of the way in which our democratic society is organized. Vast numbers of human beings must cooperate in this manner if they are to live together as a smoothly functioning society. [...] In almost every act of our daily lives, whether in the sphere of politics or business, in our social conduct or our ethical thinking, we are dominated by the relatively small number of persons [...] who understand the mental processes and social patterns of the masses. It is they who pull the wires which control the public mind."

An oft-cited example of Bernays's techniques was his campaign for the Lucky Strike tobacco company to market cigarettes to women as "torches of freedom" in the early twentieth century. This was the time of first-wave feminism and the suffrage movement, when women were beginning to organize and fight for their right to vote, and to be granted equal rights in other areas of society. The term "torches of freedom" tapped into women's collective desire for equal treatment and liberation from historical oppression and repression in its various forms, even though smoking had nothing to do with any of these aims. The campaign was successful, and a sharp increase in sales of cigarettes to women occurred as a direct result.

Bernays thus played a significant role in the emergence of mass consumption and the related phenomenon of reification. He did so in particular by focusing less on the function of a commodity and more on psychologically linking the commodity with abstract desires and attributes. To take a modern example of the same approach, when a famous athlete, like Michael Jordan, is hired to appear in advertisements for Nike sneakers, consumers subconsciously buy into the belief that they can acquire talent and fame like Jordan's by purchasing the advertised product. The object itself is seen to be imbued with those human characteristics.

Adorno, Horkheimer and the Frankfurt School

In 1947, German philosophers and sociologists Theodor W. Adorno and Max Horkheimer published their seminal book Dialectic of Enlightenment. The book was heavily influenced by Marxist and Freudian theories, and became one of the most central texts for the Frankfurt School. Political philosopher Claudio Corradetti explains that "[t]he Frankfurt School, known more appropriately as Critical Theory, is a philosophical and sociological movement spread across many universities around the world. [...] Some of the key issues and philosophical preoccupations of the School involve the critique of modernity and capitalist society, the definition of social emancipation, as well as the detection of the pathologies of society. Critical Theory provides a specific interpretation of Marxist philosophy with regards to some of its central economic and political notions like commodification, reification, fetishization and critique of mass culture". Philosopher Andreas Matthias writes that "[w]hat united the Frankfurt School was, first, an interest in Marxism and the question why Marxist teachings had not succeeded in creating the ideal society".

Sociologist Nicki Lisa Cole notes that "[o]ne of the core concerns of the scholars of the Frankfurt School, especially Horkheimer, Adorno, [Walter] Benjamin, and [Herbert] Marcuse, was the rise of 'mass culture.' This phrase refers to the technological developments that allowed for the distribution of cultural products - music, film, and art - on a mass scale. [...] They objected to how technology led to a sameness in production and cultural experience. Technology allowed the public to sit passively before cultural content rather than actively engage with one another for entertainment, as they had in the past. The scholars theorized that this experience made people intellectually inactive and politically passive, as they allowed mass-produced ideologies and values to wash over them and infiltrate their consciousness."

As journalist Peter Thompson explains, Adorno and Horkheimer's book "arrives at a pessimistic view of what can be done against a false system which, through the 'culture industry', constantly creates a false consciousness about the world around us based on myths and distortions deliberately spread in order to benefit the ruling class." One chapter in particular, "The Culture Industry: Enlightenment as Mass Deception," turned out to be highly influential on the later development of the theory of "The Spectacle." The chapter, as Matthias explains, begins "with a criticism of mass culture, which they diagnose as having lost any significance or meaning and having become just commercial entertainment. Adorno and Horkheimer write in this chapter that "[a]ll mass culture under monopoly is identical, and the contours of its skeleton, the conceptual armature fabricated by monopoly, are beginning to stand out. Those in charge no longer take much trouble to conceal the structure, the power of which increases the more bluntly its existence is admitted. Films and radio no longer need to present themselves as art. The truth that they are nothing but business is used as an ideology to legitimize the trash they intentionally produce."

For Adorno and Horkheimer, the "culture industry" is all-pervasive. They assert that "[t]he whole world is passed through the filter of the culture industry". They also note that this has specific psychological effects on the consumer: "[t]he withering of imagination and spontaneity in the consumer of culture today need not be traced back to psychological mechanisms. The products themselves, especially the most characteristic, the sound film, cripple those faculties through their objective makeup.[...] The products of the culture industry are such that they can be alertly consumed even in a state of distraction". In this way, Adorno and Horkheimer's concept of "the culture industry" closely resembles Debord's later conception of "the spectacle."

Guy Debord and the Situationist International

Guy-Ernest Debord was a French Marxist theorist, philosopher, filmmaker, and artist. In 1950, at the age of 19, he joined the radical Paris-based collective of artists and intellectuals known as the Lettrists, founded in the mid-1950s by Romanian-born poet and artist Isidore Isou. Debord led a faction of Lettrists that broke away in 1952 to form the Lettrist International (LI). Both the Lettrists and the Lettrist International had their roots in Dadaism and Surrealism, aiming to disrupt traditional approaches to poetry, and, by extension, all forms of art and ways of being in the world. What Debord added, however, was a stronger left-leaning and anti-capitalist political focus.

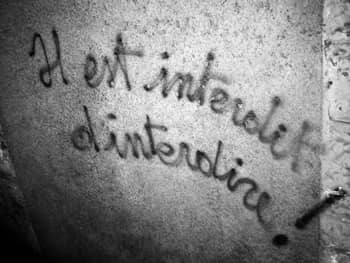

The Lettrist International developed into the Situationist International (SI), a group that officially formed under Debord's direction in 1957. Other key members of the group included Danish artist Asger Jorn, Dutch artist Constant Nieuwenhuys, and English artist Ralph Rumney. The members of SI sought to decentralize art production, often working collaboratively and refusing to attribute works to a single individual. They were also among the first modern artists to employ graffiti in their work. For example, they painted the phrase "Sous les pavés, la plage!" ("Under the paving stones, there is a beach!") around the streets of Paris, after it was discovered in May 1968 by students participating in the Paris revolt that the cobblestone streets were laid atop sand.

Art critic Laurence Debecque-Michel states that it was "in artistic circles that the Situationists had made their first headway. Noting the flop of Dadaism and Surrealism, when it came to changing life by transforming society, and advancing the real and the imaginary hand-in-hand, a certain number of figures involved in these same areas of ideas came together to express their desire to carry out research in free experimentation, where 'art was exceeded'. [...] It was above all Guy Debord who issued a harsh denunciation of any possibility of salvage by the market and museums."

Expounding on connections between art and social revolution, Debord wrote in 1963: "[t]he situationist movement can be seen as an artistic avant-garde, as an experimental investigation of possible ways for freely constructing everyday life, and as a contribution to the theoretical and practical development of a new revolutionary contestation. From now on, any fundamental cultural creation, as well as any qualitative transformation of society, is contingent on the continued development of this sort of interrelated approach.[...] Once it is understood that this is the perspective within which the situationists call for the supersession of art, it should be clear that when we speak of a unified vision of art and politics, this absolutely does not mean that we are recommending any sort of subordination of art to politics. For us, and for anyone who has begun to see this era in a disabused manner, there is no longer any modern art, just as there has been no constituted revolutionary politics anywhere in the world since the end of the 1930s. They can now be revived only by being superseded, that is to say, through the fulfillment of their most profound objectives."

As art historian Andreja Velimirović notes, "Situationism as an art movement did not produce too many artworks - as a matter of fact, if one somehow takes Asger Jorn and his pieces out of the Situationist equation, the movement's output is next to none. However, Situationism is credited with providing some of the most revolutionary theories at the time, concepts that heavily impacted the art scenes for decades." He adds that "[t]he connection between Situationism and art is extremely diverse because the members of the group came from such different backgrounds. That fact makes Situationism one of the most interesting gems of modern art to explore, but it also poses a challenge to anyone interested in such an endeavor. Another troubling occurrence to confidently analyzing the art of Situationism is that a number of members never stayed steady with their conceptual basis, constantly evolving alongside the collective."

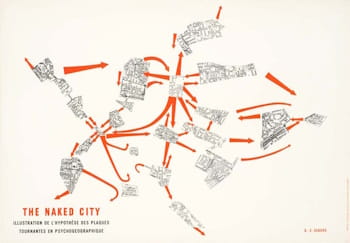

SI members were also interested in human geography, and sought ways to challenge prescribed methods of moving through urban environments. Debord developed this interest into the field of psychogeography, which he defined as "the study of the precise laws and specific effects of the geographical environment, consciously organized or not, on the emotions and behavior of individuals." He and other SI members developed the idea of the dérive, which involved aimless wandering through city streets, for many hours or even days at a time, with the intention of experimenting with new ways of exploring and experiencing the city. Some enduring SI works are maps that were cut up and reorganized.

The Society of the Spectacle (1967)

In 1967, Debord published The Society of the Spectacle, in which he laid out the theory he had been developing over the past two decades. The book consists of 221 sections (of one paragraph each) divided into nine chapters. In this book, Debord described the concept of the Society of the Spectacle "not [as] a collection of images [but] a social relation among people, mediated by images."

1) Appearances and the Preeminence of Vision

• "Everything that was directly lived has receded into a representation."

• "The spectacle is an affirmation of appearances and an identification of all human social life with appearances."

• The spectacle "naturally elevates the sense of sight to the special preeminence once occupied by touch."

2) Power and Capital(ism)

• The spectacle "is nothing other than the economy developing for itself."

• "The root of the spectacle is that oldest of all social specializations, the specialization of power."

• "The spectacle's social function is the concrete manufacture of alienation."

• "The spectacle is capital accumulated to the point that it becomes images."

3) Inauthenticity, Falseness, Copying, and Plagiarism

• "In a world that has really been turned upside down, the true is a moment of the false."

• "The loss of quality that is so evident at every level of spectacular language, from the objects it glorifies to the behavior it regulates, stems from the basic nature of a production system that shuns reality. The commodity form reduces everything to quantitative equivalence."

• "Ideas improve. The meaning of words plays a part in that improvement. Plagiarism is necessary. Progress depends on it. It sticks close to an author's phrasing, exploits his expressions, deletes a false idea, replaces it with the right one."

There were three major sub-themes that Debord presented, which pertain to art and the consumption of creative media: 1) the reduction of all lived experience into mere representation and illusion; 2) the amassing and concentration of capital and power; and 3) the loss of quality and authenticity as a result of excessive copying and allusion.

Concepts and Styles

The concept of "The Society of the Spectacle" has influenced artists working in a wide range of contemporary arts movements, styles, and media, many of which also fall under the umbrella of the term "postmodernism".

Situationist International

Artists who seek to offer a critique of the Society of the Spectacle (working in a range of styles, from Conceptual, to Pop, to Street Art) often employ specific tactics developed by Debord and other members of the Situationist International (SI). Thus, the SI can be seen as absolutely central to the development and circulation of the idea.

One tactic made famous by the SI is détournement, which art historian Andreja Velimirović describes as "the idea of recontextualizing an existing work of art or literature in order to radically shift its meaning to a new one which had revolutionary significance." Often, détournement involves making what was originally intended to appear somber or profound seem farcical, stupid, or contemptible. Marcel Ducham's L.H.O.O.Q (1919), in which a cheap postcard reproduction of Da Vinci's Mona Lisa is defaced with a moustache and beard, can be seen as an example of detournement before the fact, calling attention to the way popular culture degrades and debases true artistic creativity.

Velimirović also notes that the SI were among the first modern artists to use graffiti. Debord, for example, spent much of 1952 painting the slogan Ne travaillez jamais! ("Never work!"), a popular SI motto, around the streets of Paris. Other popular SI slogans that appeared graffitied around Paris include: "In the decor of the spectacle, the eye meets only things and their prices," "In a society that has abolished every kind of adventure the only adventure that remains is to abolish the society," "We want structures that serve people, not people serving structures," "Politics is in the streets," "The most beautiful sculpture is a paving stone thrown at a cop's head," "Art is dead, don't consume its corpse," "Commodities are the opium of the people," and "The more you consume, the less you live."

CoBrA

Many SI members had previously been part of the CoBrA group of artists (which preceded the SI by about a decade). In the aftermath of World War Two, CoBrA artists sought to critique the ideology of the bourgeoisie, what sociologist Bartholomeus Landheer calls the "hard, merciless spirit of individualism, materialism, and hedonism" fostered by modern capitalist society. CoBrA artists also turned away from traditional notions of "high art" and conventional artistic institutions, instead favoring "Outsider" and "Primitive" art, and collaborative projects such as magazines and murals. Even before Guy Debord formally defined "the Society of the Spectacle", CoBrA artists such as Asger Jorn, Karel Appel, and Constant Anton Nieuwenhuys were making art that challenged an idea of the Society of the Spectacle by pushing against conventional ideas of beauty and taste.

Institutional Critique

The phrase "institutional critique" refers to the practice of using art to criticise galleries, museums and other arts institutions, including how they are run, how they impose restrictions and limitations on artists, and how they are funded (as well as how they perpetuate a money-driven art market). Debord's writing on the Society of the Spectacle influenced the now-common idea that critiquing artistic institutions could be a central aspect of an artistic practice. He argued, for example, that in the age of the spectacle, it was impossible for artistic institutions to allow true engagement with artistic creativity because the experience of inhabiting those institutions was so thoroughly defined by the play of illusions generated by capitalism. "In this age of museums in which artistic communication is no longer possible, all the previous expressions of art can be accepted equally, because whatever particular communication problems they may have had are eclipsed by all the present-day obstacles to communication in general."

Beginning in the late 1960s, this kind of institutional critique emerged as a dominant aspect of postmodern artistic discourse, most notably amongst Conceptual artists, as well as Installation artists, Land artists, Graffiti and Street artists. Conceptual artists engaged in institutional critique by refusing to produce a tangible art object, instead offer concepts or ideas as artworks in themselves. In this way, artists prevented their creative output from being commodified. This was described as the "dematerialization of art" by the critics Lucy Lippard and John Chandler in their 1968 article of the same name. The result can be seen in works like Hans Haacke's MoMa Poll (1970), an installation work in which visitors were asked to deposit slips of writing into a box giving their answer to a contemporary political issue.

Performance Art

The development of Performance art was one major outcome of the idea of the Society of the Spectacle, which perpetuated the idea that true artists must push through the layers of illusion involved in experiencing conventional, visual and three-dimensional artworks in a capitalist society. Performance artists engaged in institutional critique and the "dematerialization" of art by developing live performances (often involving the artist's own body) instead of producing art objects that can be bought and sold (though documentation of these performances in photos and other objects often become commodities).

In Museum Highlights: A Gallery Talk (1989), performance artist Andrea Fraser performed the role of a museum guide, giving a tour of the Philadelphia Museum of Art, in which she parodied and exaggerated the pretentious, even inaccessible language often used by arts institutions. Other performance artists, like Yoko Ono, Marina Abramović, and Ulay, have given performances in which audiences are forced to engage directly with the performers' bodies. Often the aim is to make clear to the viewer the central role of the artist in the museum-going experience, something which can be lost through engaging with inert (yet highly-prized) objects.

Pop Art

From the mid-1950s to the late 1970s, Pop artists in the UK and US developed a style that focused on mimicking the widely-disseminated images and mass-produced commodities of contemporary capitalist society. This resulted in a blurring of boundaries between "high art" and "low [or popular] culture. Andy Warhol, for example, famously presented images of Campbell's Soup cans and film-stars like Marilyn Monroe and Elvis Presley as works of art.

Warhol, and other Pop artists like Roy Lichtenstein also adopted the methods and aesthetics of mass production, most famously at Warhol's "Factory," a studio at which his screenprints were produced in huge numbers, with a deliberate lack of attention paid to the quality of each individual object. Lichtenstein, meanwhile, created painstaking painted reproductions of the Ben-Day-dot illustrations found in cheap action comics. In both cases, the aim was partly to emphasize the commodity status of the art object in the modern world. In short, pop artists sought to demonstrate that, as Debord asserted, "[c]ommodification is not only visible, we no longer see anything else; the world we see is the world of the commodity."

Later Developments

Jean Baudrillard: Simulacra and Simulation (1981)

In 1981, French sociologist Jean Baudrillard published his treatise Simulacra and Simulation, which further developed Debord's concept of the Society of the Spectacle. Just as Debord wrote that the spectacle "obliterates the boundaries between true and false by repressing all directly lived truth beneath the real presence of falsehood maintained by the organization of appearances," Baudrillard asserted that "simulation threatens the difference between the 'true' and the 'false,' the 'real' and the 'imaginary'." In fact, Baudrillard directly refers to Debord's ideas in his text, while presenting the alienation his own text describes as more profound, more impossible to escape from, than that which Debord had identified. "We are no longer in the society of the spectacle, of which the situationists spoke, nor in the specific kinds of alienation and repression that it implied [...] This spectacle, which is at once that of the death throes and the apogee of capital, surpasses by far that of the commodity described by the situationists. This spectacle is our essential force."

For Baudrillard, in other words, the simulacrum, unlike the spectacle, is not a form of distortion that hides the truth, but itself comes to constitute the truth. Or rather, its total pervasiveness proves that the idea of truth is now an illusion. Simulacra and Simulation opens on a quote falsely attributed to the Bible: "[t]he simulacrum is never that which conceals the truth - it is the truth which conceals that there is none. The simulacrum is true." He goes on to explain that "[s]imulation is no longer that of a territory, a referential being, or a substance. It is the generation by models of a real without origin or reality: a hyperreal." In other words, "signs of the real" have come to "replace the real."

![According to Baudrillard, places like Disneyland exemplify “simulacra,” in that they “present as imaginary to make us believe that the rest [of the world] is real,” when in reality contemporary Western society is “no longer real,” but “hyperreal.”](/images20/photo/photo_society_of_the_spectacle_10.jpg)

Baudrillard offers up Disneyland as an example of "a perfect model of all the entangled orders of simulacra," writing that "[t]his imaginary world [...] exists in order to hide that it is the 'real' country, all of 'real' America that is Disneyland [...] Disneyland is presented as imaginary in order to make us believe that the rest is real, whereas all of Los Angeles and the America that surrounds it are no longer real, but belong to the hyperreal order and to the order of simulation. It is no longer a question of a false representation of reality (ideology) but of concealing the fact that the real is no longer real."

Postmodernism

In influencing a more all-encompassing idea of the spectacle than he himself proposed - such as that outlined by Baudrillard - Debord also helped to usher in the age of postmodernism in art. The distinction between modernism and postmodernism can be simply described as follows: whereas for modernists such as Debord there remained the possibility of access to some true or authentic version of reality, for postmodernists such as Baudrillard, that possibility was extinguished. Illusion was all. Media theorist Alan N. Shapiro thus describes Baudrillard's theory of simulacra and simulation as a "postmodernist" version of Debord's "modernist" theory of the spectacle.

Many critics would contrast the post-modern period of the late twentieth century and early twenty-first century with the modernist period of the late-nineteenth and early-twentieth centuries. However, Historian of philosophy Brian Duignan presents postmodernism as a reaction against a wider paradigm, namely "the intellectual assumptions and values of the modern period in the history of Western philosophy (roughly, the 17th through the 19th century)." In other words, postmodernism can be seen as reacting not just to modernism, but to the whole of post-Enlightenment western culture.

The "modern" assumptions which Duignan sees as opposed by postmodernism include the idea that "[t]here is an objective natural reality, a reality whose existence and properties are logically independent of human beings - of their minds, their societies, their social practices, or their investigative techniques." Postmodernism, Duignan argues, also disputes the modern idea that "[t]he descriptive and explanatory statements of scientists and historians can, in principle, be objectively true or false." Finally, postmodernism disputes the idea that, "[t]hrough the use of reason and logic, and with the more specialized tools provided by science and technology, human beings are likely to change themselves and their societies for the better." In contrast, postmodern thought understands that "there is no such thing as 'truth'," and that, like "truth," "logic" and "reason" "are merely conceptual constructs."

The postmodern perspective has been reflected in art since about the 1950s. However, the term "postmodern" was first introduced to the world of philosophy by French philosopher Jean-François Lyotard in his 1979 book The Postmodern Condition: A Report on Knowledge. Postmodern artists, Lyotard argued, challenged the "grand narratives" that characterized the modern period, such as the belief that progress (particularly technological and scientific progress) is always inherently positive, and the belief that there exist "totalizing" theories that explain broad developments in history or the development of knowledge. The racism, colonialism, sexism, and other problematic isms that characterized art history through the modern period are also heavily critiqued by postmodern artists, and seen as evidence of the failures of the entire post-Enlightenment project.

Artists working in a range of contemporary styles and movements, from Pop Art to Conceptual Art to Feminist Art, can be considered postmodern. In this sense, they can also be seen as influenced by the idea of the Society of the Spectacle.

Useful Resources on The Society of the Spectacle

- The Society of the SpectacleOur PickBy Guy Debord

- PropagandaBy Edward Bernays

- Public RelationsBy Edward Bernays

- Dialectic of EnlightenmentOur PickBy Max Horkheimer and Theodor W. Adorno

- Guy DebordOur PickBy Anselm Jappe

- Debord, Time and Spectacle: Hegelian Marxism and Situationist TheoryBy Tom Bunyard

- Simulacra and SimulationOur PickBy Jean Baudrillard

- The Spectacle 2.0: Reading Debord in the Context of Digital CapitalismBy Emiliana Armano and Marco Briziarelli

- Postmodernism, or, The Cultural Logic of Late CapitalismOur PickBy Fredric Jameson

- Marx and ArtBy Ali Alizadeh

- Post Modern Art: 1945-NowBy Francesco Poli

- Art Of The Postmodern Era: From The Late 1960s To The Early 1990sOur PickBy Irving Sandler

- The Disappearance of Objects: New York Art and the Rise of the Postmodern CityBy Joshua Shannon

- Signs of Psyche in Modern and Postmodern ArtOur PickBy Donald Kuspit

- The Postmodern Arts: An Introductory Reader (Critical Readers in Theory and Practice)Our PickBy Nigel Wheale

- Postmodern Perspectives: Issues in Contemporary ArtOur PickBy Howard Risatti

Ask The Art Story AI

Ask The Art Story AI