Summary of Guillaume Apollinaire

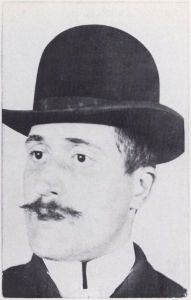

The name of Guillaume Apollinaire is synonymous with the rise of the early-twentieth-century avant garde. A fixture of Parisian café society, he rubbed shoulders with other young bohemians, making friends with numerous artists including Raoul Dufy, André Derain, Maurice de Vlaminck and Pablo Picasso. Though not a painter himself, nor formally schooled in art history (unlike, say, Vasari or Greenberg, writers who brought their own indominable influence to bear on Renaissance Art and Abstract Expressionism respectively), he was an enthusiastic, infatigable, champion of the modernists, and is credited with alerting these kindred spirits to the new artistic horizons opened up by studying African masks and the "naïve" paintings of Henri Rousseau. Through his lyrical art criticism, for which he remains best remembered, Apollinaire did more than any other writer of his generation in establishing the legends of some of the most important artists of the century.

Accomplishments

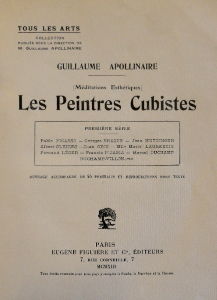

- Apollinaire set himself the task of defining the key principles of the burgeoning Cubist movement. His one full-length book, Peintures cubistes (Cubist Painters) was published in 1913 and was at that time considered the most authoritative book on the movement and its aesthetics. Though his poetic style was considered by some to be a little verbose, the book confirmed Apollinaire's reputation as a modern art critic to be reckoned with.

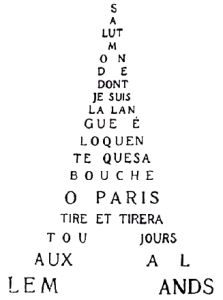

- Through his poetry, Apollinaire set out to disorient his reader by means of incredulous verbal associations. Indeed, Apollinaire's poetry was considered daringly experimental and this was especially true of his so-called "calligrammes" which featured an ingenious typographic arrangement whereby the words of his poem were arranged in a way that formed an image (the Eifel Tower, for example).

- Apollinaire's enthusiasm for modern art saw his words matched by actions. It was he who instigated one of the most significant partnerships in the history of art when he introduced Georges Braque to Pablo Picasso. He was also active in organizing, and speaking at, several of the Cubist movement's most important exhibitions.

- Having already introduced the term "surrealism" into the lexicon of modernist terms, Apollinaire coined the name "Orphism" to describe a brand new movement. He saw the need to distinguish the colorful and harmonious patched compositions of Robert Delaunay from the more austere elements of Cubism. Apollinaire was a great supporter of Delaunay who he championed as the very epitome of what a progressive artist should be. He took the name Orphism from the mythological Greek poet and musician Orpheus since it related to the idea that painting could share similarities with the beauty and scope of music.

The Life of Guillaume Apollinaire

This sculpture by Picasso, Head of a Woman (Dora Maar) was unveiled in 1959 as an homage to Apollinaire. To this day, the tribute stands in the garden next to the church in the intimate St-Germain-des-Prés neighborhood in Paris.

Guillaume Apollinaire and Important Artists and Artworks

Women Bathing (1900)

Five nude women in the woods, clustered in a circle in a variety of seated, crouching, and standing positions dominate the foreground of Paul Cézanne's painting. While the women are engaged in the basic act of cleansing, here in the artist's masterful hands they possess a sense of graceful movement and rhythm which imbues the act of bathing with an almost sensual quality. A masterpiece of Post-Impressionism, the forest background in which the figures are placed is rendered in loose brushstrokes of brown, greens, and yellow. For Apollinaire, "the trees in these delicate landscapes are so alive that they appear almost human".

When considering the pantheon of nineteenth-century artists, Apollinaire wrote that "Paul Cézanne must be reckoned one of the greatest". During his short career, he wrote many reviews of key Parisian exhibitions and salons. It was during a review of a 1910 exhibition of Cézanne's work at the Bernheim Gallery that he specifically distinguished his paintings of women bathing as proof of his skill in extending the long tradition of female nudes into the realm of modernity. He wrote "[the painting] constitutes a formidable argument against the critics who used to tell us in their inimitable fashion that Cézanne did not know how to paint nudes".

Oil on canvas - Collection of Ny Carlsberg Glyptotek, Copenhagen, Denmark

Acrobat and Young Harlequin (1905)

Early in his career, Picasso took as his subject humble performers for a series of paintings such as this one depicting a young man dressed in a red clown costume who rests his hand on the shoulder of a boy posing in an acrobat's leotard with a multicolored diamond design. Even before heralding his development of Cubism, Apollinaire discussed some of Picasso's early paintings, including those of performers, in one of his first articles about the artist. Written for the May 1905 issue of La Plume magazine, it was, according to author Leroy Breunig, "the first serious piece to appear on the Spanish painter, and for Apollinaire it was only the beginning of a series of eulogies of the artist whom he considered without question the greatest of his generation".

Set against a background of barely discernible buildings, the scene is rendered in a soft palette of blues, browns, and white and yet the presence of the vibrant shades of red in both the outfits and pot of flowers behind them firmly place this work among those of the artist's rose period. Even here, however, Apollinaire was able to see the modernity in Picasso's approach and he acknowledged how in this work, "color has the flat quality of frescoes, and the lines are firm". Distinguishing Picasso's style from the art of the past, Apollinaire added that, "one cannot confuse these saltimbanques [acrobats] with mere actors on a stage. The spectator who watches them must be pious, for they celebrate wordless rites with painstaking agility. This is what distinguishes this painter from the Greek potters, whom his drawing sometimes calls to mind. On the painted vases, bearded, verbose priests sacrificed resigned animals bound to destiny. In these paintings virility is beardless, but it manifests itself in the muscles of the skinny arms and flat cheekbones, and the animals are mysterious".

His praise for this painting is an important contribution to the writer's faith in the young Pablo Picasso's potential. There was something Apollinaire admired about the stark humanity of these figures. Brought to life through Picasso's capable hands, they are not mere figure studies, but rather suffering creatures whose lives are spent in the role of entertaining others which, according to Apollinaire, was supported by the observation that "the cheeks and brows of taciturn clowns are withered by morbid sensibilities".

Oil on canvas - Barnes Foundation, Philadelphia, Pennsylvania

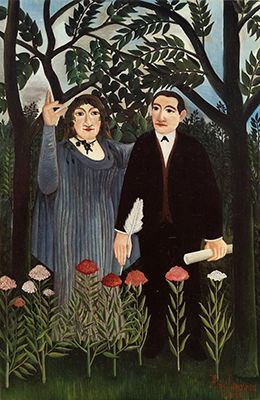

The Muse Inspiring the Poet (1909)

In The Muse Inspiring the Poet (the second of two versions featuring this subject), Rousseau has shown a couple standing in a landscape with trees in the background and a row of pink, red, and white flowers in front of them. Here Rousseau has in fact depicted Apollinaire with his then girlfriend, artist Marie Laurencin, appearing as his muse, arm raised in a fashion reminiscent of the mythological goddess of the art of antiquity. Here Rousseau pays homage to the creative genius of Apollinaire by depicting him holding a scroll of paper and feather quill pen.

Interestingly, when the work was created many failed to recognize Apollinaire's likeness in the male figure. This shocked the poet who wrote of it in 1914, "some found the painting touching, others thought it bordered on the grotesque, but as far as the resemblance was concerned, everyone was in agreement: there was none at all". However, Apollinaire felt the painting accurately represented him stating, "I tend to think that that portrait was such a good likeness - at once so striking and so new - that it dazzled even those who were not aware of the resemblance and did not want to believe in it. Painting is the most pious art".

Oil on canvas - Collection of Oeffentliche Kunstsammlung, Basel, Switzerland

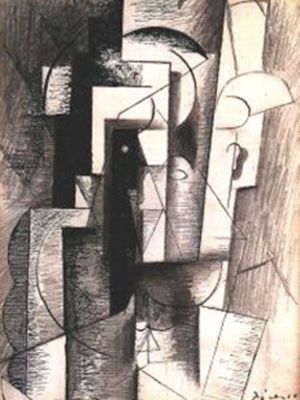

Study for the portrait of Guillaume Apollinaire (1911)

In this work on paper, Jean Metzinger has depicted Guillaume Apollinaire, seated with arms crossed in front of him, well dressed in suit and tie and smoking a pipe. On the table in front of him is a drink and the tools of his trade; sheets of paper and a pen. Rendered in the Cubist style, the subject is depicted in crisp geometric lines while sitter and table seem jammed into the foreground of the picture plane.

In what can only be seen as an act of reverence, many of the artists that Apollinaire promoted during his career took him as their subject. While no direct copy of this work exists in painted form (although Metzinger did create an earlier painted portrait), his later work Man with Pipe (Le Fumeur) (1912-13) which bears some similarities to this study is believed to be either a portrait of poet Max Jacob or Apollinaire. More than just a physical representation of the subject, here Metzinger has captured the essence of a close friend. Known for his dapper dress sense and what author Francis Steegmuller describes as the sometimes, "false impression of extravagance", he is here depicted as well dressed and with his trademark pipe of which friend Fernande Olivier said, "it was always with a pipe in his mouth or in his hand that he told his stories, always with a very serious air even when they were trivial or rollicking".

That Apollinaire's portrait would be a Cubist work is fitting and he called attention to Metzinger whom he described as, "one of the most appealing figures among today's young French painters. Believing him to be an important figure in the Cubist movement, Apollinaire once wrote of his works that the "attractiveness they all possess proves that the discipline of cubism is not incompatible with reality". In Metzinger, he found proof that Cubism was more than a passing phase and rather a strong force in shaping the trajectory of modern art.

Graphite on paper - Collection of Musée National d'Art Moderne, Centre Pompidou, Paris, France

The City of Paris (1912)

Delaunay's painting is a celebration of Parisian modernity. In describing the work, Apollinaire wrote, "on the left, the Seine and Montmartre; on the right, the Eiffel Tower and some houses: in the center, three slim, powerful figures who critics claim are copied from the wall paintings of Pompeii but who nevertheless are incarnations of French grace and power".

Apollinaire was mesmerized by this painting when it debuted at the 1912 Salon des Indépendents and wrote of it more than once. Calling it, "the most important picture in the Salon," it represented for him the next important step in modern art, Orphism. According to Apollinaire, this painting was, "more than an artistic manifestation. This painting marks the advent of a conception of art that seemed to have been lost with the great Italian painters. And [...] it also epitomizes, without any scientific paraphernalia, all the efforts of modern painting. It is broadly executed. Its composition is simple and noble. And no fault that anyone might find with it can detract from this truth: It is a painting, a real painting, and it has been a long time since we have seen anything of the kind".

Apollinaire's praise of this work provides a glimpse into his own ideas of what modern art can and should be and the reason why he wanted to be its champion. Apollinaire praised Delaunay as, "one of those rare painters of the younger generation who, after taking part in all the foremost artistic movements, has now cut himself off from them in a reaction against their exclusively decorative tendencies. Robert Delaunay's art is full of movement and does not lack power. Rows of houses, architectural views of cities, especially the Eiffel Tower - these are the characteristic themes of an artist who has a monumental vision of the world, which he fragments into powerful light".

Oil on canvas - Collection of Georges Pompidou Center, Paris, France

Portrait of Guillaume Apollinaire (1913)

This work on paper features a bust portrait of Apollinaire. Created in the Cubist style, here Picasso has depicted the figure in a composition of broken-down geometric shapes and black lines and sharp contrasts of white and dark. An immediate kinship was established when Picasso and Apollinaire met in 1904 with the two bonding over the desire to break with the past and push forward in an embrace of a modern future that would change art and literature. Apollinaire would go on to be a major promoter of Picasso's art praising him in articles by describing him as, "heir of all the great artists of the past. Having suddenly awaken to life, he is heading in a direction that no one has taken before". Recognizing him as a figurehead for modernism, he stated, "he is a new man and the world is as he represents it. He has enumerated its elements, its details, with a brutality that knows, on occasion, how to be gracious".

Apollinaire's celebration of Picasso was not one-sided. Picasso made several sketches and drawings of the poet during the years of their friendship. He even attempted to create a memorial tribute to Apollinaire after his death, but according to journalist Jonathan Jones, his "design for an abstract Monument to Apollinaire was rejected as too odd to stand in Paris's Père Lachaise cemetery". This work is arguably his most impressive portrait of Apollinaire because it was created in a fitting example of the Cubist movement; a style he and Georges Braque founded having been first introduced by Apollinaire himself.

Pencil and Chinese ink wash on paper - Private Collection

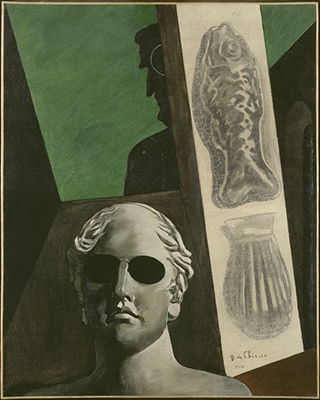

Portrait of Guillaume Apollinaire (1914)

A double portrait of sorts, this painting features a stone bust of poet Apollinaire depicted in the foreground wearing sunglasses. Positioned in the front of a dark brown interior, on the right there is a column on which hangs molds of a fish and a shell. In the background set against a green sky, Apollinaire can once more be seen in profile silhouette with a white circle partially visible on his head. A sense of foreboding is present in this work with the dark figures and open spaces that are both characteristic of Giorgio de Chirico's style and a forerunner of Surrealism (despite the artist never aligning himself with the movement).

In this portrait, de Chirico pays homage to Apollinaire who helped to promote the key art movements of the twentieth century. He has been preserved here in marble which is symbolic of forefathers of other fields that have been recorded in the same material - a tribute dating back to the days of Ancient Greece. According to critic Jonathan Jones, "he looks right at us, however: his blindness is that of the seer, the poet [...] This painting belongs to a series on the theme of the poet as type [...] the poet sees or engenders visions of impossible conjunctions: the moulds of a fish and a shell on unresolved Renaissance architecture, and the silhouette of a man [Apollinaire] on whose head a white circle has been drawn [...] So in this painting the spirit of Apollinaire, embodied by the bust, has a deathly vision of Apollinaire, the flesh-and-blood man".

Apollinaire's respect for di Chirico is evident in his writings; saying of this work that it was a "harmonious and mysterious compositions in the midst of silence and meditation". The painting is all the more powerful in that it foreshadows Apollinaire's own death. As Jones explains, "in 1914, de Chirico painted Apollinaire in silhouette with what looks like a target down on his cranium. Apollinaire enlisted in the French army in the first world war and in 1917 was severely wounded - in the head.[...] De Chirico's Premonitory Portrait is a menacing masterpiece of the 20th century, a dream of death that happened to come true".

Oil on canvas - Collection of Georges Pompidou Center, Paris, France

Bather (1915)

A hybrid of painting and sculpture, in this work Alexander Archipenko depicts a bather stepping into a bright blue body of water. Cubist in style, the golden-yellow colored figure is rendered via basic geometric shapes. According to the object label for this work from the Philadelphia Museum of Art, the work was created while Archipenko spent time in the Mediterranean during the duration of the First World War as he was unfit to serve: "lacking the proper facilities for making large-scale sculpture, the artist turned to what he called 'sculpto-painting,' a collage medium in low relief. While this female bather was undoubtedly inspired by real-life swimmers that Archipenko would have seen on the beach during his time in Nice, the presence of a delicately shaded classical column imbues the composition with a timeless quality".

Archipenko excited Apollinaire mostly because of his willingness to challenge the idea of what sculpture could be. Of the artist he wrote, Archipenko, "seeks above all the purity of forms. He wants to find the most abstract, most symbolic, newest forms, and wants to be able to shape them as he pleases". Here he took the traditional notion of the bather, a longtime subject in art history and revised it. Writing in praise of the work, Apollinaire stated, "Archipenko's daring constructions timidly but firmly proclaim the singularity of this new art [...] that unites internal plastic structure with the supreme charm of a sensuously beautiful surface. The archings, the complementary forms, the differentiation of planes, the hollows and the reliefs, never abruptly contrasted, are transformed into living stone that the passionate touch of the chisel has endowed with sculptural expression. Let us look at [...] this Bather who, ever-changing, appears ever-new".

Oil paint, graphite, paper, and metal on panel - Collection of Louise and Walter Arensberg Collection, Philadelphia Museum of Art, Philadelphia, Pennsylvania

Biography of Guillaume Apollinaire

Childhood and Education

Much of the early years of Apollinaire Guillaume's life are steeped in mystery. Born Wilhelm Apollinaris de Kostrowitzki; his Polish mother Angelica, daughter of a Vatican official, did not acknowledge his birth in public records until he was a little over a month old. He was never told who his father was (although he was generally believed to be an Italian officer) and it became the source of much speculation as his reputation grew. This was fueled in large part by Apollinaire's later claim that he was in fact descended from nobility.

A free-spirit, Apollinaire's mother moved him and his younger brother, Alberto, to Monte Carlo in 1887 where she was supported by the men with whom she cohabitated. Despite her lack of motherly instincts, she saw to it that Apollinaire received a privileged education at the Collège Saint-Charles. An unpopular student, he threw himself into his studies and began writing which would be the starting point for his career as a poet. His future role as an art critic was not nurtured in school, however, and his knowledge in this field would be largely self-taught. Of the limited time he did spend in an art class he later stated, "when I recall the drawing class at school, I remember the awful lithographs they used to give us as models - works without artistry by unknown drawing teachers whose solemnity and lack of daring were equaled only by their unskillfulness. Their timid scribbles were enough to impart a distaste for art even to those students who would later come to adore it".

Early Training

Longing for adventure, an eighteen-year-old Apollinaire obtained a job with a wealthy German family as a French tutor for their daughter. The teaching post provided him with the opportunity to travel throughout Europe for the next four years. It was during this period that he engaged in an intense affair with the family's English governess, Annie Playden, who would later refuse his marriage proposal and move to America to escape his attentions. Apollinaire's heartbreak was such he was inspired to write "Chanson du mal-aimé" ("Song of the Poorly Loved"), widely considered his most important early poem, and a piece that brought playful and bizarre imagery to traditional verse.

Once his tutor position had ended, Apollinaire moved to Paris where he held a series of jobs including working as a bank clerk for six years which he did to support himself as he pursued his writing. After his first few poems were published in local magazines, he decided to change his name to the more dramatic and mysterious Guillaume Apollinaire. At this time he also became a frequent presence in Parisian bars and cafes where he would recite his own poetry to the patrons.

Mature Period

Apollinaire's first foray into art criticism and journalism came through the magazine, Le Festin d'Esope which he helped create in 1903. While the publication ran for only nine issues, it was here that he included his first art criticism, a paragraph that dismissed the more classical French art of the period in favor of the emergent Fauvist style. His engagement with this movement began in part with a chance meeting with Fauve artists, André Derain and Maurice de Vlaminck. The three immediately formed a bond in their shared interest in embracing modernity (in both art and literature), and according to author Francis Steegmuller, Apollinaire found, "objective confirmation of his ideas coming from artists whose vision was new and alive". The first of what would be a career-long review of artworks and exhibitions, this early writing is testament to his impassioned interest in the world of modern art. He stated, "today, there are only modern painters who, having liberated their art, are now forging a new art in order to achieve works that are materially as new as the aesthetic according to which they were conceived".

Apollinaire became a fixture in the Parisian art world following a meeting with Pablo Picasso that took place in a bar in 1905 and which had been arranged through a secretary named Jean Mollet. Kindred spirits from the start, Picasso introduced Apollinaire to poet Max Jacob who later reflected on their meeting: "the three of us went out, and we began that life of three-cornered friendship which lasted almost until the war, never leaving one another whether for work, meals, or fun". Apollinaire's relationship with Picasso, opened up the art world to him and almost immediately he began writing about the artist. The author Leroy Breunig credits Apollinaire's writing on Picasso in May 1905 in La Plume as being, "the first serious piece to appear on the Spanish painter".

Perhaps Apollinaire's most important contribution to the art world at this time came when he introduced Georges Braque to Picasso in the latter's studio in 1907. The two began working together immediately and would soon after develop Cubism. Apollinaire thoroughly embraced this new movement as everything modernism should be: "Cubism is the art of depicting new wholes with formal elements borrowed not only from the reality of vision, but from that of conception", he said. Apollinaire would go on to publish many articles and provided public lectures on the subject.

It was around this time that Apollinaire began a relationship with artist Marie Laurencin. Picasso introduced the two at an art gallery in 1907, telling Apollinaire, "I have a fiancée for you." Of their instant attraction, Apollinaire stated, "she's like a little sun - a feminine version of myself". Bonded by their love of art and shared family backgrounds of strong mothers and illegitimate births, the two were together for six years during which time Apollinaire wrote in high praise of her art and described how, "purity is her natural sphere; she breathes in it freely". While the relationship did not last, their love was forever memorialized through Henri Rousseau's painting The Muse Inspiring the Poet (1909) which featured a portrait of the couple.

Apollinaire's support for Cubism earned him the reputation of being the champion of the most important artists of the day; he became in many ways a modern-day version of Giorgio Vasari who had done so much to promote the work the Italian Renaissance artists. Apollinaire also began reviewing all the major art exhibitions and salons of Paris including serving as a contributing author for the newspaper L'Intransigeant for four years from 1910. In addition to Picasso and Braque, he helped promote the work of artists such as Alexander Archipenko, Robert Delaunay, Wassily Kandinsky, Aristide Maillol, Henri Matisse, and Jean Metzinger. According to author Roger Shattuck, "at some stages he produced a short article every day. He discussed everything, from amateur kitsch out of Brittany to the annual official Salon to the most provocative gallery shows". A symbiotic relationship developed between Apollinaire and these artists and Steegmuller suggested that, "if what the painters found in Apollinaire was a friend and a poet doubling as a promoter, what he found in them was what Braque has said - a group of sympathetic personalities: artists of his own age, with talent or genius, who gave him stimulus and the courage to recognize in himself the only living poet he knew with a vision as fresh as theirs". This mutual appreciation is nowhere more evident than in the portraits Picasso and others made of Apollinaire and the articles he wrote in support of their work.

Fully absorbed in the bohemian lifestyle of Paris, stories abound of Apollinaire's exploits including supplementing his income by writing erotica under a false name so as not to damage his reputation. Picasso's one time lover Fernande Olivier described him as, "a mixture of distinction and a certain vulgarity, the latter coming out in his loud, childish laugh. [...] What struck you above all was his evident good nature. He was calm and gentle, serious, affectionate, inspiring confidence the moment he spoke - and he spoke a great deal". According to Steegmuller, Apollinaire also "experimented with opium-smoking, [and even] pretended for more than a year to be a woman poet named Louise Lalanne" in order to review the work of other female poets more freely.

While Apollinaire's reputation steadily grew through the early years of the twentieth century, a single event in 1911 rocked his reputation bringing him both notoriety but also anxiety and depression. On August 21, 1911, Leonardo da Vinci's masterpiece the Mona Lisa (1503) was stolen from the Louvre museum. Apollinaire wrote an article about the theft for the L'Intransigeant newspaper in which he described the ineptitude of the museum's security: "the situation is one of carelessness, negligence, indifference". Ironically, not long after, his former secretary Gery Pieret approached Apollinaire showing him two statues he had stolen from the Louvre. Concerned, Apollinaire returned the statues to the museum on Pieret's behalf. Although not connected to the da Vinci theft at all, his connection to Pieret led him to be arrested by police on September 9th under suspicion of harboring a criminal and his potential knowledge about an international art theft gang of which they believed Pieret to be a member.

Friends rallied to show their support for Apollinaire and according to Steegmuller, "petitions protesting his arrest, signed by many artists and writers, were delivered to the police and the investigating magistrate". Of this time, Apollinaire later wrote, "I learned that the Press was defending me, that writers who are the honour of France had spoken in my favour, and I felt less alone". He was eventually released when no evidence could be found linking him to the theft (the Mona Lisa was later recovered in 1913 in Florence having been stolen by Vincenzo Peruggia, an Italian housepainter who believed the painting should be returned to its rightful home).

Of the impact of this event, author Roger Shattuck wrote, "six days in prison both traumatized him and brought a useful celebrity". Anyone who did not know who Apollinaire was before the theft certainly did after. He underwent a period of depression after the incident with his greatest fear, according to Steegmuller, being that he might be, "expelled from France as an undesirable foreigner" (it proved an unfounded anxiety when Apollinaire achieved his life's dream of being made a French citizen on March 9th, 1916).

Taking part in the creation of a new magazine, Soirées de Paris in 1912 helped to buoy Apollinaire's spirits after the da Vinci incident. Important articles about art were included in the publication including writings about Robert Delaunay and his new style of art, Orphism, which Apollinaire felt was the future of modern art. He was also impressed by a new Italian art movement, Futurism, after meeting artists Umberto Boccioni and Gino Severini and he wrote a highly complementary introduction about the motivations behind the new style for a Futurist magazine. While Apollinaire admired their ambition, he was possibly hesitant about any movement not born in France and also wrote more critically of the movement and what he felt was its lack of originality, stating, "Futurism, in my opinion, is an Italian imitation of the two schools of French painting that have succeeded each other over the past few years: fauvism and cubism".

1913 proved an important year for Apollinaire's critical reputation. He published what would be his only full-length book, Les Peintres Cubistes, and an anthology of poems, Alcools. According to Steegmuller, the former was "widely referred to as 'the first book on Cubism' [although in reality another book had been published a year earlier]" while Alcools, which would come to be regarded as his masterpiece, featured reflections on his experiences, expressed in unrhyming lines and without punctuation, of life in the cafes and bars of Paris.

Later Period

The last years of Apollinaire's life were consumed with war. He enlisted in the French army's 38th Artillery Regiment in 1914. According to Steegmuller, "being a foreigner, he was not obliged to enlist. He could have sat out the war in a neutral country, or like Picasso, in France itself; or he could have gone to New York and seen something of his friends Marcel Duchamp, Francis Picabia, and Albert Gleizes"; all artists he had helped promote through his writings. Instead he chose to defend the country he loved. Ever the wordsmith, of his enlistment he joked, "I so love art that I have joined the artillery".

Apollinaire corresponded with two women during his enlistment (these letters were later published in two famous volumes: Lettres à Lou (1947) and Tendre comme le souvenir (1952)). He had fallen in love with Louise de Coligny-Châtillon ("Lou") following a short affair just before the war. The couple maintained daily correspondence and his letters reveal his attempts to win her back. Apollinaire's letters get more terse, however, during 1915 when his affections had transferred to Madeleine Pagès, a professor of letters at the lycée de jeunes filles in Oran, whom he had met on a train journey while returning from leave. His letters to Pagès move from the courteous to the daring and the couple declared their love for each other in the summer of 1915. Apollinaire and Pagès spent a period of 15 days leave together in December 1915 but following a life-threatening shrapnel injury, Apollinaire retreated into convalescence and refused to receive her visits (his last letter to Pagès is dated November 1916).

On March 17, 1916, Apollinaire was seriously injured after shrapnel splinters became embedded in his temple. Rushed to surgery, the fragments were removed but he suffered additional trauma and later in May had to undergo a second surgery to remove pressure on his brain.

While recovering from his injury, Apollinaire worked with an increased energy. He had, with his 1903 play Les Mamelles de Tirésias (The Breasts of Tirésias), used the term "surrealist" for the first time. The play's first production came in 1917 when it carried the subtitle Drame surréaliste with the notes to the play advising that the term "surrealism" described a brand new style of drama. A year later Apollinaire invented the calligram, an entirely new type of poem which consisted of words arranged in such a way as to create an image that enhanced the meaning of the poem itself. He also continued to write art criticism including a piece about the newly developing art of cinematography. The term "surrealism" also began to circulate, appearing in the program notes for the ballet Parade created by Sergei Diaghilev, Erik Satie, Picasso and Jean Cocteau. It would soon be adopted by a new artistic movement being developed at that time, Steegmuller noted, "Apollinaire had unquestionably invented the term surrealist [and] the surrealists have always esteemed him, and have tended to claim him as one of their immediate ancestors".

On May 2, 1918 Apollinaire married the nurse Jacqueline Kolb, a woman he had met prior to the war. While he could have retired due to his injury, he was not released by the army and instead was promoted to the rank of first lieutenant and given a post in the department of the Ministry of Colonies. It was here that he would have most likely served through to the end of the war but in early November he fell victim of the great flu epidemic of 1918. He succumbed to the illness on November 9 at the young age of thirty-eight. According to Steegmuller, a friend, Louise Faure-Favier, later related the story told to her by his wife that on his deathbed Apollinaire was said to have, "begged the doctor to cure him [and cried] 'Save me, doctor! I want to live! I still have so many things to say!".

A blow to the worlds of art and literature, Apollinaire's death touched many. Perhaps it was Picasso who felt the loss of his beloved friend most profoundly. Steegmuller explains how, "Picasso is said to have received the news of Apollinaire's death while shaving [and] Struck by his own mournful expression, he replaced razor by pencil, and [...] apparently the last self-portrait Picasso ever drew, has been called [...] a 'farewell to youth', and, even more sentimentally, a 'memorial to his friend Apollinaire'".

The Legacy of Guillaume Apollinaire

In addition to his contributions to the field of poetry; Apollinaire left a lasting legacy in the art world. Profound in its impact, he helped to shape the direction of early twentieth century modern art. While some have criticized his lack of formal art education, the power of his words speak for themselves. Through his writings he helped secure the legends of numerous modern artists including Alexander Archipenko, Georges Braque, Paul Cézanne, Giorgio de Chirico, Robert Delaunay, André Derain, Marie Laurencin, Fernand Léger, Jean Metzinger, Pablo Picasso, Henri Rousseau, Maurice de Vlaminck, and Wassily Kandinsky; and he was instrumental in promoting the key movements of Cubism, Fauvism, Futurism, Orphism, and Surrealism. His impact has been preserved in numerous portraits by some of the very artists he celebrated. Perhaps the most impressive of these is the memorial sculpture Picasso created of his friend in 1959; which is located in the park of the St. Germain des Pres church in Paris.

In addition to a rich body of publications about art and artists, the author Leroy Breunig suggests that in some ways "his reputation in Paris as the champion of modern art was in fact based more on deeds than on published works" and that in addition to introducing Braque and Picasso, it was "he who had helped organize the cubist Room 41 at the Salon des Indépendents of 1911; established liaison between the Montmartre and the Puteaux cubists; lectured at the important Section d'Or exhibit in 1912; [...] baptized orphism and became its champion at a Delaunay show in Berlin; launched and directed the Soirées de Paris, one of the principal organs of the avant-garde before the war; issued a manifesto for futurism; and coined the term surrealism".

Influences and Connections

-

![Pablo Picasso]() Pablo Picasso

Pablo Picasso -

![Raoul Dufy]() Raoul Dufy

Raoul Dufy -

![Marie Laurencin]() Marie Laurencin

Marie Laurencin ![Max Jacob]() Max Jacob

Max Jacob- Paul Guillaume

Ask The Art Story AI

Ask The Art Story AI