Summary of Albert C. Barnes

Having amassed a vast fortune through his pharmaceutical company, Barnes became a philanthropic art collector who built the world famous Barnes Foundation. The Foundation, which houses one of the most impressive collections of modern art in the United States, came with a charter to promote "the advancement of education and the appreciation of the fine arts" for all sections of American society. Barnes brought together many of the world's greatest masterpieces including works by European titans such as Renoir, Cézanne, Matisse, Picasso and Modigliani. Notwithstanding a richly-deserved reputation as a fractious and obstinate individual, Barnes was a strong advocate of progressive education and social equality and worked closely with African American communities, championing indigenous African art and doing much to launch the career of the African American artist, Horace Pippin. The Barnes Foundation currently displays paintings and sculptures alongside African masks, native American jewellery, Greek antiquities, and pieces of decorative metalwork.

Accomplishments

- The Barnes Foundation was a triumph of art and philanthropy. Whatever his shortcomings as a rounded individual, his commitment to the betterment of public life was indisputable. He conceived of his Foundation as a means of demystifying fine art and his great success was to break down the elitist attitudes that dogged art education and appreciation. His Foundation's abiding contribution to the life of Philadelphians proved to be a gift to the cultural life all Americans.

- Having commissioned Matisse to provide the centrepiece for the Foundation's vast main gallery, Barnes can take credit for reinvigorating the Frenchman's flagging career. Though the sheer scale of The Dance proved to be a truly gruelling undertaking for the artist (not helped by the cantankerous behaviour of Barnes) it saw Matisse return to the emphasis on forms and color that distinguished his early career. In terms of his artistic development, the large dance-like cut-outs, formed around arched architectural backgrounds, would dictate Matisse's later work.

- Barnes had long held an interest in African art and African American culture. Having attended a solo exhibition of an unknown Horace Pippin in Philadelphia in 1940, Barnes bought several pieces for his collection and extended an invitation to Pippin to enrol at the Foundation as a student. Barnes became Pippin's greatest champion and even wrote an essay on the artist in lieu of his second solo exhibition in 1941.

- While Barnes is better known perhaps for his promotion of European art, this was not to the neglect of modern American artists. Indeed, in addition to his support for Pippin, he did much to raise the profile of homegrown artists, some of whom were associated with the New York Ashcan School. He formed lasting (if typically bumpy) friendships with American artists such as William Glackens, Alfred Henry Maurer, Maurice Prendergast, John Sloan and Charles Demuth.

The Life of Albert C. Barnes

Barnes was an uncompromising figure, "What we are trying to do at the Foundation has never been attempted before", was his claim. His goal was to reveal art; to, in his words, "link an objective study of pictures to the powers possessed by every normal human being and to do it with the aid of respectable educational methods".

Albert C. Barnes and Important Artists and Artworks

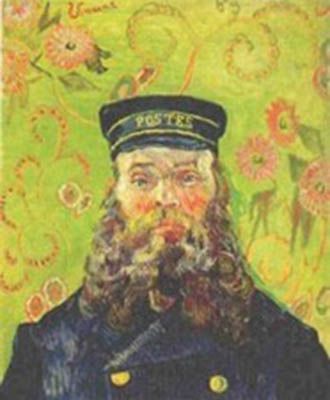

The Postman (Joseph-Étienne Roulin) (1889)

The sitter for this portrait is Vincent van Gogh's friend, a stoic mail carrier named Joseph-Étienne Roulin who the artist met while living in the French town of Arles. This, one of six portraits van Gogh made of Roulin, features the subject staring directly out at the viewer with his long curly brown beard cascading over the front of his gold buttoned jacket. He stands in sharp contrast to the green wallpaper with large pink flowers that form the backdrop. According to art historian Martha Lucy, Roulin's uniform, complete with cap, describes "not only a sitter's occupation but also perhaps his political leanings; as an ardent socialist, he would have worn his worker identity proudly. Moreover, the uniform announces that portraiture is no longer reserved for the upper classes". This work is an important example of the value the artist placed on his friends by including them often in his paintings. As the Barnes Foundation website states, "the two [men] shared similar left-leaning political views and became close friends; in fact it was Roulin who cared for Van Gogh during his hospital stay in nearby Saint-Rémy".

As a strong admirer of Post-Impressionism, van Gogh was highly revered by Barnes. This painting is one of the thirty-three paintings which made up his first collection. They were purchased by artists Alfred Henry Maurer and William Glackens at the behest of Barnes during a European buying trip in February 1910. Thereafter, Barnes made all his own future purchases, but he was grateful to his buyers, and especially, Glackens for his astute selections. Indeed, these pieces would lay the foundations for what was destined to become America's finest collections of late-eighteenth and early twentieth century European modernism.

Oil on canvas - Collection of Barnes Foundation, Philadelphia, Pennsylvania

Young Woman Holding a Cigarette (1901)

In this portrait, Picasso has depicted a young woman seated in a chair. Looking out at the viewer with an absent gaze, she cradles her left arm at the elbow while holding a cigarette between two long fingers. Compositionally balanced, her dark blue blouse matches the blue picture on the wall diagonally across from her; while the orange of her skirt matches her hair which she has swept up in a large bun. An important work in Picasso's career, it marked his transition to his Blue Period. According to art historian Judith Dolkart, Picasso was newly inspired after his first trip to Paris in 1900 where, having "heartily plunged into the city's renowned and debauched nightlife [he] immediately began to paint colorful images of dance halls and demimondaines. She adds that Picasso now "began to make such subjects distinctively his own as he incorporated the cerulean tonalities and melancholy mood of his ascendant Blue Period".

This work was the first Picasso Barnes owned. Purchased on his behalf by his friends Maurer and Glackens on a European buying trip in 1910, it became, according to Dolkart, "a foundational object in the collection". For his part, Barnes traveled to Paris for the first time in 1912. He met fellow American collectors Gertrude and Leo Stein and through them he was introduced to Picasso and the dealer, Paul Guillaume (who would become Barnes's main European supplier after World War I). He also purchased seven works by Picasso from the dealer Daniel-Henry Kahnweiler, including Picasso's Head of a Man and Head of a Woman (both 1907). But while Barnes would purchase many more Picassos in his lifetime, the majority were drawn from his early years since Barnes was not fond of the Cubist movement. Indeed he wrote an article in 1916, titled "Cubism: Requiescat in Pace" in which he stated that Cubism was "academic, repetitive, and dead" and dismissed it as "a typical commercial venture". As author Howard Greenfeld put it, "Cubism did not meet the aesthetic principles [Barnes] had formulated, and he was unable to understand it". Barnes he did, however, judge works on their individual merits and acquired selective Cubist pieces including Jacques Lipchitz's, sculpture, Bather (1917).

Oil on canvas - Collection of Barnes Foundation, Philadelphia, Pennsylvania

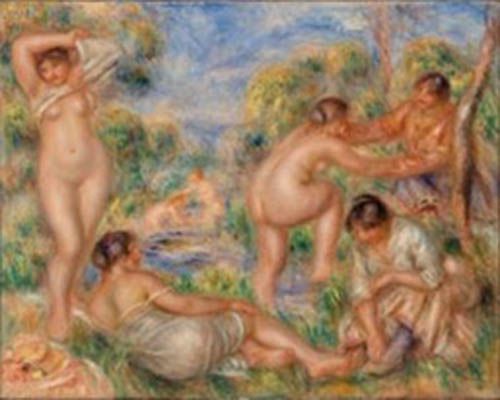

Bathing Group (Les Baigneuses) (1916)

Renoir's painting features a group of women, in various stages of undress, relaxing and frolicking around a patch of blue water. Like the figures themselves, the cloud-filled sky and green-leafed trees are painted in the loose brushstrokes and a vibrant color palette that was characteristic of the artist's work. This work is an important piece in Renoir's oeuvre. Painted late in his career, Bathing Group shows the maturity of Renoir's approach to painting female nudes in motion. As art historian Martha Lucy explains, "what Barnes and other critics admired about Renoir's late production was the premium placed on design. A work such as Bathing Group was sensual but not lacking in control: compositionally, all parts added up to a unified whole".

Renoir was one of Barnes's favorite artists and over his many decades of collecting he purchased nearly two hundred works by the artist. He once stated, "I am convinced I cannot get too many Renoirs". According to Lucy, "when asked in a 1924 letter to name his favorite work by Renoir [...] Barnes landed firmly on this painting. 'My large canvas, 'Es Baigneuses' [Bathing Group] represents the summation of [Renoir's] powers,' he wrote. Unlike other collectors of the time, who generally favored Renoir's impressionist pictures, Barnes considered the artist's later work the pinnacle of his career".

Oil on canvas - Collection of Barnes Foundation, Philadelphia, Pennsylvania

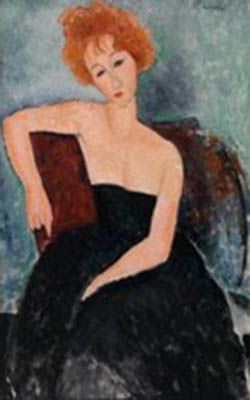

Redheaded Girl in Evening Dress (1918)

This painting is a fine example of the portraits for which Modigliani became best known. The woman who dominates the canvas possesses all the elan associated with the typical "Modigliani figure" including an elongated neck, oval shaped face, and eyes and head cocked provocatively to one side. The Barnes Foundation homepage says of this piece, "[Modigliani's] portrait of an unidentified sitter, with her vivid hair and strapless dress, suggests how women's lives had changed by the early 20th century. Draping her shoulder over the chair, she addresses the viewer with an unapologetic gaze. Her revealing dress shows how bold new fashions could represent a form of freedom".

Barnes added several Modigliani portraits to his collection and was attracted to the Italian artist circuitously through his passion for early African sculpture. Speaking of the connection between the two, Barnes stated, "if the long, attenuated necks of Modigliani figures seem absurd or grotesque, go to the University Museum and look at the even longer necks on the pieces of ancient African sculpture, so rich in art values. Then you will see that Modigliani's inspiration came from his devotion to the spirit of negro art and that experience did something to him and he did something to it by his imagination and reason".

Oil on canvas - Collection of Barnes Foundation, Philadelphia, Pennsylvania

Woman in Blue (1919)

This painting is a fine example of the troubling way in which Soutine saw the sitters he depicted with something the Barnes Foundation website describes as "a searing psychological intensity". Characteristic of his artistic style, here his figure is an unsettling one, shadowed in darkness, and rendered with rough, gestural brushstrokes. In describing this painting, art historian Judith Dolkart states, "although Chaim Soutine did not identify his sitter, he endowed her with an unforgettable, even terrifying, specificity in his rendering of her hunched posture, enormous misshapen hands, and lopsided staring eyes. Soutine suggested the back of a chair behind the uneven shoulders of the model, but the blues of her dress and the upholstery merge, further heightening the sense of deformity and contortion".

Barnes played an important role in the career of Soutine. The pair were introduced by dealer Paul Guillaume who, according to author Howard Greenfeld, "led the collector to the discovery of a totally unknown [...] Soutine - a discovery that would make the painter famous and add immeasurably to [Barnes's] reputation". His first experience with the paintings was a profitable one for both the collector and the artist and, as Greenfeld explains, "Guillaume led him to the home of Zborowski, to whom Soutine had consigned most of his completed paintings. Barnes was overwhelmed by what he saw: the distorted figures, chaotic landscapes, and tormented flowers so moved him that he immediately offered to buy everything in sight. Estimates of the number of canvases vary from fifty to a hundred; what is certain is that Barnes paid 60,000 francs ($3,000) for his acquisitions". Later, Barnes would say of Soutine, "he ranks with Matisse and Picasso as one of the painters whose experiments and ideas have had the most profound influence upon contemporary painting".

Oil on canvas - Collection of Barnes Foundation, Philadelphia, Pennsylvania

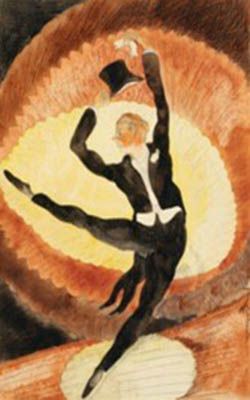

In Vaudeville: Acrobatic Male Dance with Top Hat (1920)

Vaudeville and cabaret performance was a recurrent theme in Demuth's oeuvre. According to Lucy, such subject matter, fill "his watercolors from around 1915 to 1920. Here, a silhouetted vaudeville performer kicks one leg out to the side, his rippling contours cutting a sharp image against the bright lights behind him. The figure's movements are graceful, balletic, as he balances skillfully on one toe [...] Though small, the watercolor is bursting with energy". This work shows the modern approach to performers that Demuth has captured on paper resulting in expressive treatments of his subjects. Lucy adds that, "Stage lights are represented by concentric rings of red and yellow - thin washes of color through which parallel pencil lines appear that reiterate the sense of outward movement. The light also seems to represent the energy emanating from the performer himself".

While Barnes had the greater interest in European art, he was also drawn to some early modern American artists, thanks in no small part to his high school friend, the artist Glackens, who introduced him to some of his colleagues, including Demuth. As was often the case, the artists Barnes collected also became his friends. As Lucy explains, "long before Barnes established the Foundation, Demuth, who lived for a time in Philadelphia, would visit the collector at his home, where they discussed modern art. Barnes greatly respected the opinion of his friend 'Deem' and bought many watercolors directly from the artist". Still, Barnes was a notoriously opinionated man, and as Greenfeld explains, "the two men had their disagreements - especially over the merits of Demuth's mentor and friend, John Marin, whose work Barnes refused to buy in spite of Demuth's efforts - but their friendship survived these disagreements".

Watercolor, graphite, and charcoal on wove paper - Collection of Barnes Foundation, Philadelphia, Pennsylvania

Dr. Albert C. Barnes (1926)

The main portion of this portrait is dominated by the subject, Albert Barnes. He is depicted wearing a gray suit, seated at a desk, and looking out towards the right side of the frame with his head resting on his hand. He is lost in thought. It is the background, however, with its incomplete architectural structures, an open archway, and a faceless mannequin figure, which makes it unmistakably a painting by de Chirico.

The French art dealer Paul Guillaume was responsible for introducing Barnes to de Chirico. Barnes was so impressed by the Italian he would eventually purchase twenty-five of his paintings. According to Greenfeld, their relationship, "was a formal one, based largely on intellectual affinity and mutual convenience. They were not close companions, but Barnes's admiration for the artist's work was such that he agreed, in 1926, to write the foreword to a catalogue of an important exhibition held in Guillaume's gallery. In it he praised the artist's ideas as those of a sage and a scholar, characterizing him as a mystic, a poet, and an independent man. De Chirico returned the compliment. That same year, he executed two portraits of Barnes".

Oil on canvas - Collection of Barnes Foundation, Philadelphia, Pennsylvania

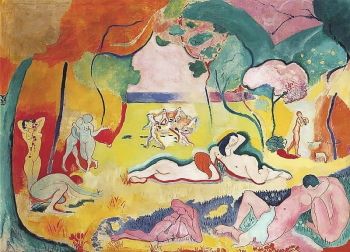

The Dance (1932-33)

Barnes and Matisse met in 1930 after the Frenchman had been invited to judge the Carnegie Medal in New York. Art Historian Philip McCouat writes that at that time "Matisse had just turned 60, and was at somewhat of a crossroads. Artistically, he had lost some of his inspiration for painting. He had recently returned from a trip to Tahiti, which had been intended to recharge his batteries, but from which he derived few short-term results. [...] He had also been subject to devastating criticism from some critics that he had been coasting, particularly during his so-called Nice period, and that his best days were long behind him. Financially, too, there were problems. He was badly affected by the fall in art prices resulting from the Crash. Coupled with his dwindling stocks of painting, this meant some financial pain for Matisse".

Barnes invited Matisse to decorate a 50 square meters area of the two-storey main gallery. The pair negotiated a fee of $30,000 (paid in three instalments) for a project that was estimated to last 12 months. As McCouat states, "This was a welcome break for Matisse, and he saw it as a chance to raise his profile and reach out to a new public in America. For an artist who had largely been involved with small, private art, he was excited at this new challenge of producing public, monumental art". The sheer scale of the project meant that Matisse would have to return to Nice. Once in Southern France, he rented a large garage space where he hung the massive canvases and, using charcoal and a long bamboo stick, drafted his figures. As he proceeded, Matisse realized he would need to significantly modify his original design and, effectively restarting from scratch, he abandoned his freehand technique in favor of paper cut-outs. He was a good year into the project when he realized a further error, this time to do with width of the piece which he had miscalculated.

The mural was finally completed in March 1933 but, as McCouat remarked, "By this stage [Matisse] was so stressed that he abandoned plans to exhibit the work in Paris before transporting it to America". Matisse travelled to Philadelphia to oversee, the installation of the work but more despair was to follow. Firstly, Barnes turned down Matisse's request to have two paintings situated below the mural removed, and secondly, Barnes refused to remove the ornamental frieze situated at the mural's base. McCouat states that the "tension became so great that, during the installation, Matisse suffered a seizure". But he adds that "the final bombshell was still to come" when Barnes, who was perfectly happy with the finished work, "shocked Matisse by telling him that he had no intention of letting the public see it. Matisse was naturally devastated, describing Barnes privately as a "monster of egotism" who was concerned only with the mixed reception that had greeted his recently-released The Art of Henri-Matisse [a book written by Barnes] The upsetting result was that, once Matisse left Merion, he never saw the painting again. Very few others did either, until well after Barnes' death. Even colour reproductions of the painting, like other works at Merion, were strictly forbidden".

Oil on canvas - Collection of Barnes Foundation, Philadelphia, Pennsylvania

Supper Time (1940)

In this domestic scene, painted on a burnt wood panel, Pippin has depicted a family in their sparsely furnished home. A father is seated at a table along with her daughter whose back is to the viewer. The mother, who illuminates the picture frame with her bright blue dress, white apron and white headscarf, serves the family meal. Behind them, white laundry items dry on a line. The material on which the painting is rendered plays a key role in the overall effect of the work. As Lucy says, "in this small work painted on wood [...] Pippin leaves much of the panel exposed so that it becomes an active part of the composition. Unpainted wood establishes the table and the view through the window; it also forms the skin of all three figures". Lucy adds that "Pippin, who was self-taught, "developed a technique of 'carving' into his panels with a hot poker. Here, burnt-wood lines (incised over pencil) construct the chair, windowpanes, door panels, and contours of the figures".

Barnes had long had an interest in African American culture and was already a collector of African art before he learned of Pippin and decided to help further his career. As Lucy explains, "Pippin had his first solo exhibition in 1940 at the Robert Carlen Galleries in Philadelphia, where several of these burnt-wood panels were displayed. Albert Barnes, who was increasingly interested in the work of self-taught artists, bought several paintings from the exhibition and invited Pippin to visit the Foundation. Pippin even enrolled briefly as a student. A great champion of the artist's work, Barnes wrote an essay for Pippin's second exhibition at Carlen Galleries in 1941".

Oil on burnt-wood panel - Collection of Barnes Foundation, Philadelphia, Pennsylvania

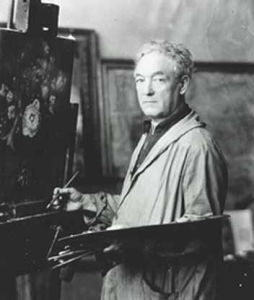

Biography of Albert C. Barnes

Childhood and Education

Albert Coombs Barnes was the third of four sons born to parents Lydia and John Barnes. His father was a postal worker who had had a career as a butcher before losing an arm in the American Civil War. His childhood can best be described as difficult. Raised in a working-class neighborhood in Philadelphia, and bullied at school, he also suffered the loss of two siblings. Despite (or probably because of) these setbacks, Barnes developed a steely determination and self-belief that saw him excel in his school studies.

Lydia Barnes had a profound impact on her son's life including sparking his interest in African American culture. According to writer Dr. Sylvia Karasu, "one of the most significant - even 'religious' - experiences of his life occurred when he first heard black spirituals sung at a camp meeting to which his mother had taken him as a young child". Lydia saw the value in culture and saw to it that her son was taught art and music from an early age. These interests stayed with him through high school where Barnes made friends with classmate, and future artist, William Glackens. Of their relationship, Barnes later stated, "we became close friends, partly through my interest in his drawing [...] and because we had the same interest in sports".

Early Education

In 1889 Barnes enrolled in medical school at the University of Pennsylvania which he helped pay for with a series of part-time jobs. Having graduated, he realized that it was the research side of medicine that he was most interested in and headed for Europe where he studied chemistry at the University of Berlin.

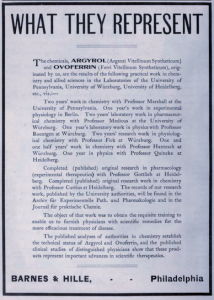

On his return to Philadelphia in 1896, Barnes began working at the pharmaceutical firm, H. K. Mulford Company in their advertising and sales division. He convinced the company to hire a brilliant young chemist, Hermann Hille, whom he had recently met in Germany. With Hille, Barnes began testing compounds which led to the discovery of a cheap-to-produce silver nitrate solution that was successful in treating blindness in babies born to mothers with venereal disease. They named their product, Argyrol. Using his advertising and sales acumen, Barned devised an aggressive and successful advertising strategy that encouraged the pair to start their own company, Barnes & Hille. In the summer of 1900, Barnes met Laura Leggett and the couple were married six months later. This happy period in his life coincided with successful sales of Argyrol (including to the French Army which used it to treat venereal disease amongst its troops) making Barnes an extremely wealthy man. As a public symbol of his elevation in society, he built a mansion in Merion, Pennsylvania, in 1905 which he named Lauraston to honor his wife.

Career

Although sales for Argyrol remained impressively strong, the relationship between Barnes and Hille was badly deteriorating. It was the start of a pattern with Barnes in which many of his friendships and working partnerships began strongly but ended in acrimony. In May 1907, Barnes brought an action against Hille and a year later a judge ordered that the partnership be resolved with the top bidder taking control of the company. Barnes won and renamed the company the A.C. Barnes Company. As sole owner, Barnes implemented what was a revolutionary employment policy mandating a six hour workday with an optional two hours of educational classes and programs intended to enrich the lives of his workforce. As the historian Philip McCouat writes, Barnes "was an early and active supporter of disadvantaged groups, including Afro-Americans, provided generous employee conditions and benefits for his workforce (which he ensured were mixed-sex and racially integrated), and had a great and genuine commitment to worker education".

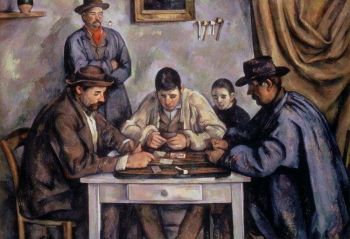

Having accumulated such great wealth, Barnes turned his focus to one of his earliest passions, art. According to author Howard Greenfeld, "[Barnes] knew he could never be a successful painter (he reached this conclusion, he remembered later, after having completed 190 canvases), so he decided to do the next best thing - collect the works of other painters. 'I collected my own pictures when I didn't have money,' he wrote, 'and when I had money I collected better ones'". In 1910 Barnes handed American Ashcan School painter Alfred Henry Maurer, and his former classmate Glackens, himself a reasonably accomplished painter, $20,000 to buy paintings in Paris. They returned with over twenty works by artists including Paul Cézanne, Vincent van Gogh, Camille Pissarro, and Pierre-Auguste Renoir, most of which were bought from the art dealer Paul Durand-Ruel. Barnes was so grateful for this early support that when the next year Glackens had to have surgery, Barnes returned to the role of doctor to oversee his friend's operation.

Barnes soon began making art purchases on his own working directly with Parisian dealers; most notably Paul Durand-Ruel and Paul Guillaume. During his numerous trips to Europe, Barnes made other important connections too, including the Stein siblings (Gertrude and Leo) from whom he bought his first two Matisse paintings and an early Picasso (which, according to McCouat, "cost him only a pittance") in 1913. Barnes and Gertrude Stein (both notoriously "strong personalities") did not bond but he formed a good working friendship with Leo. Indeed, Barnes later commented, "it is safe to say that my talks with [Leo Stein] in the early days were the most important factor in determining my activities in the art world".

Once Barnes set his mind to becoming an art collector it became an all-consuming pursuit. As author John Anderson noted, "the years 1922-1923 would arguably be the most important of Barnes's whole career as a collector. During that period alone, he made more than one hundred purchases". It was while touring Europe that Barnes developed a special interest in Impressionist, Post-Impressionist and African art. He was an early collector, too, of artists including Jacques Lipchitz, Amadeo Modigliani, and Chaim Soutine. In addition to his European and African pieces, he collected works by American artists including Glackens and other associated with The Ashcan School such as Maurice Prendergast and John Sloan. While Barnes is credited with purchasing his first painting, Sloan also provides a good example of the often difficult relationship that developed between collector and artist. As Greenfeld explains "[Sloan] was very unhappy that Barnes had such a possessive attitude about his collection. Sloan felt that a true collector should feel like a 'custodian' of works of art". Barnes saw things differently, however, believing that having purchased a work he became its rightful owner.

Having amassed such an impressive collection, the next logical step for Barnes was to create a suitable space to house the works. As he said, "my collection of pictures got beyond me. People wanted to come to see it from all over the world. And the teachers of art, and the painters, wanted to bring their classes there". In 1922 Barnes purchased a 12-acre plot in Merion (suburb of Philadephia) where, having been granted a charter by the Pennsylvanian civic authorities, he established the Barnes Foundation. As the Foundation's homepage describes it, "the unique approach to teaching - now known as the Barnes Method - emphasized close looking, critical thinking, and prolonged engagement with original works of art. Dr. Barnes worked closely with his colleague Violette de Mazia to shape the program".

Barnes's ambitions were however checked by strict bylaws which included the number of staff he could employ, the two days per week it was allowed be open to the public, the number of trustees (five) which included Barnes and which gave him ultimate governing control. It was also mandated that the Barnes Foundation function as an educational institution rather than a museum. Finally, the organization's physical structure, for which he hired Paul Philippe Cret as architect, housed the art collection and educational classes together in a limestone building that adjoined the palatial Barnes residence, Lauraston.

The Barnes Foundation opened on March 19, 1925. With Barnes's friend, the philosopher John Dewey, as Director of Education, the Foundation was quickly able to offer a regular schedule of exhibitions and education classes. In addition to overseeing the operations of the Foundation and taking an active role in how works were displayed, Barnes spent a large portion of his time writing and publishing works including The Art in Painting (1925) (and later, The French Primitives and Their Forms: From Their Origin to the End of the Fifteenth Century (1931), and books on the art of Matisse, Renoir and Cézanne, in 1933, 1935, and 1939 respectively). Another book, published through the Foundation, Guillaume and Thomas Munro's, Primitive Negro Sculpture (1926), offered evidence of Barnes's interest in African culture and which was further confirmed through his support for African American artists.

As the Barnes Foundation homepage explains, By the time the Foundation was up-and-running, Barnes had become actively involved in the New Negro Movement - better known today as the Harlem Renaissance - and had joined with the philosopher Alain Locke and activist and scholar Charles S. Johnson "to promote awareness of the artistic value of African art". Indeed, Johnson wrote to Barnes in 1927 to express on behalf of the African American community his gratitude for all the Foundation's work: "I can think of no one who has been more consistent in urging this self-realization [of African Americans] than you. And to remove this from what might possibly be interpreted as merely a gracious remark, I point to that first discovery for America of the vital power of African art, and its preservation to the synthesis of Negro artistic expression in the plastic arts, music and poetry, which has been projected from the Foundation [...] I refer to these because they are very real and vital contributions to a cause, and that you may know at least that they are recognized".

Barnes wanted the majority of the visitors to the Foundation to be students who were enrolled in classes. But this policy resulted in a situation where the general public, critics and important public figures were denied admittance. This caused many tensions and when some of his pieces were exhibited at the Pennsylvania Academy of the Fine Arts, Barnes was enraged by their poor reception and dispatched strongly worded personal letters to the critics who dared to pick fault with them. As Greenfeld explains, Barnes "had been hurt and stunned by the ignorance and insensitivity of the men and women who called themselves art critics, and he never forgave them. For the rest of his life, he closed his gallery to most of these so-called experts".

McCouat offered the following overview of Barnes's combative and eccentric personality: "Over time, his growing list of enemies included journalists, art critics, dealers, other collectors, other millionaires, conservative academics and museum officials. The directness of his attacks on his opponents was notorious [...] In return, Barnes himself was regarded by his enemies as one of the more offensive men in public life". McCouat added that "Officially, access was limited to students at the Foundation, but Barnes exercised his discretion - in a characteristically eccentric way - to admit others. So, for example, he would welcome visitors like Albert Einstein, Thomas Mann or the actor Charles Laughton, but would refuse admission to other notables on the deliberately facetious basis that he was too busy trying to 'break the world's record for goldfish-swallowing', or that he was 'out on the lawn singing to the birds' [...] TS Eliot received the one-word rejection, 'Nuts'; Le Corbusier fared even worse, with 'Merde' ['shit']. Sometimes Barnes signed rejections in the name of his fictional secretary, or even his dog Fidèle-de-Port-Manech who, Barnes claimed, could understand only French".

Later Period

The Wall Street Crash of 1929 had a devastating effect on many businesses but for Barnes the Crash rather worked out in his favor. He had sold the rights to Argyrol just months prior and had great buying power with so many collectors in financial distress. McCouat adds that the timing of his sale of Argyrol was "remarkably providential in another way, as it came shortly before the invention of antibiotics, which ultimately wiped out a large part of Argyrol's market".

As Barnes continued, despite the bleak financial climate, to grow his collection, his Foundation helped to maintain relationships with several artists including Jacques Lipchitz, who designed reliefs for the exterior of the building, and Henri Matisse who visited Merion in 1930 and agreed to design a large mural for the Foundation. Matisse was given a free reign in his choice of subject and chose to return to his signature theme of dancing figures. As McCouat states Matisse "was to use this theme to produce a work that straddled painting and architecture. It would be the biggest painting that Matisse had ever undertaken, and would be his first picture of figures in motion for more than twenty years".

By the mid-thirties the Foundation had welcomed other important visitors including the painter Giorgio de Chirico and the dealer Ambroise Vollard (the man who "discovered" Cézanne). According to Greenfeld, on his visit Vollard fell down a flight of stairs to which Barnes replied, "ah, Vollard [....] If you had been killed, I would have buried you in the middle of the Foundation". The fact that both men were highly amused by the incident underlined the good relations between two giants of international art dealership.

There were two major organizations which Barnes battled with throughout his career. He fell into dispute with the Pennsylvania Museum of Art (PMA) in 1937 when an article was published praising its recently acquired painting of Cézanne's bathers which it compared unfavorably to a slightly smaller Cézanne piece held at the Foundation. According to Greenfeld, "Barnes saw the announcement as an attempt to minimize the importance of his own painting" and so retaliated with a written attack on the museum. Barnes certainly knew how to harbor a grudge. As Greenfeld explains, when Barnes found himself on a ship travelling to Europe with Joseph E. Widener, the millionaire who had acquired the (bigger) Cézanne for the PMA, and the pair were assigned adjoining seats on deck, both men were "[too] proud to request different chairs [and] also too proud to exchange a single word during the whole crossing".

In 1940, Barnes made the acquaintance of the radical English philosopher, Bertrand Russell. Russell was a "progressive" who had espoused strong opinions on (amongst other things) religion and sexual morality. Russell had arrived in America hoping to start a career as an academic taking up posts first at the University of Chicago and University College Los Angeles before arriving at the College of the City of New York. Russell's appointment in New York caused an outcry set in motion by the Episcopal Bishop of New York, Dr William Manning who attacked Russell as a "decadent defender of adultery" (adultery was still illegal in NYC at that time). A vicious public backlash followed. Although Russell garnered the support of Civil Liberties groups, and even intellectuals such as Albert Einstein, his appointment was revoked by a judge and a 68 year old Russell was left unemployed.

Having got wind of the Russell affair, Barnes invited the Englishman to join the Foundation as a philosophy lecturer. It was a very lucrative offer of one lecture per-week over five years. According to Russell's biographer, Ray Monk, Barnes saw Russell as something of a kindred spirit whereas Russell, whose lectures were a roaring success with students, "did not particularly want Barnes to be his friend or even his colleague" and saw his relationship with Barnes rather as "an opportunity to realise the kind of quiet, financially secure, contemplative life that was required to pursue serious work. He did not want to fight Barnes' battles, nor did he want Barnes to fight his; he wanted only to work in peace in the countryside, undisturbed by the demands of working journalism or engaging in polemics". The relationship between the two men reached its nadir when Russell accepted an invitation to deliver a series of lectures at the Rand School of Social Science (Barnes was already upset by Russell's wife who he had barred from entering the Foundation on learning that she had been seen knitting while attending her husband's lectures). There ensued an exchange of letters which was picked up on by the Saturday Evening Post. Once their spat was made public, an enraged Barnes dismissed Russell with just three days' notice. The Englishman sued his erstwhile employer for unfair dismissal, winning full payment for the three years remaining on his contract.

In 1947, and in his now customary belligerent manner, Barnes reignited a feud with the University of Pennsylvania which dated back as far as 1924 and a failed attempt to develop a collaborative educational program with the Foundation. In 1947, Barnes tried to develop a relationship with his alma mater's new president, Harold Stassen, and to initiate new programs at the university. When these efforts failed, Barnes permanently broke ties with the University and in 1950 used the law courts to change the Foundation's bylaws to ensure the University would have no involvement with his collection after his death. Barnes instead selected Pennsylvania's Lincoln University, a well-respected black college, to take control over nominating trustees to his Foundation following his death.

On July 24, 1951, en-route from his second home in Chester Springs to his first at Merion, Barnes failed to brake at a stop sign and his car was struck by a truck. He was thrown from his vehicle and died instantly.

Controversies over the exquisite art collection raged long after Barnes died. One involved a legal battle in 1993 which resulted in a ruling that allowed his works to go on tour, a decision that went against Barnes's express wish as laid out in his will. Furthermore, a proposal was put forward to relocate Foundation's collection to a larger building in Philadelphia. This too went against the original Foundation mission (of being a place of education rather than a commercial venue) which strictly forbid the movement of any works in the Barnes collection. Ultimately, after a multi-year legal battle, the move succeeded and the new Foundation building opened to the public in 2012.

The Legacy of Albert C. Barnes

McCouat writes: "On his death, Barnes was described as the American art world's 'most bizarre and colourful personality', as a man with a 'talent for invective' who placed a 'paralysing terror' on 'the entire American art world of his generation', and who left behind him 'more ill-will than any other single figure in American art'". Whatever one's personal feelings about "Barnes the man", no one can deny he created one of the twentieth century's greatest modern art collections. He was, according to a 1928 article in The New Yorker, the "De Medici in Merion" and helped further the international reputations of greats including Paul Cézanne, Henri Matisse, Amedeo Modigliani, Pablo Picasso, and Pierre-Auguste Renoir. His preference (once he liked an artist) was to collect many of their works, a policy that saw him also play a key role in establishing the names of up-and-coming artists including Giorgio de Chirico, Jacques Lipchitz and Chaim Soutine. In the same vein, his interest in African American culture and early African art secured it a wider audience amongst the American public while the Barnes Foundation was able to count Horace Pippin as one of its greatest alumni.

Today, Barnes's educational mission reaches 12,000 Philadelphia schoolchildren every year and promotes a variety of special exhibitions, community classes and programs for adult learners all of which uphold Barnes's commitment to arts education and inclusivity. Barnes once stated, "I am trying to do the biggest thing for Philadelphia that any one man has ever attempted", but he was not the only person to recognize the scale of his efforts. Matisse proved magnanimous enough to put aside his personal grievances against Barnes when he said, "one of the most striking things in America is the Barnes collection, which is exhibited in a spirit very beneficial for the formation of American artists. There the old master paintings are put beside the modern ones, a Douanier Rousseau next to a Primitive, and this bringing together helps students understand a lot of the things the academies don't teach".

Influences and Connections

-

![Ambroise Vollard]() Ambroise Vollard

Ambroise Vollard -

![Daniel-Henry Kahnweiler]() Daniel-Henry Kahnweiler

Daniel-Henry Kahnweiler ![Leo Stein]() Leo Stein

Leo Stein![Paul Durand-Ruel]() Paul Durand-Ruel

Paul Durand-Ruel- Violette de Mazia

-

![Giorgio de Chirico]() Giorgio de Chirico

Giorgio de Chirico -

![Charles Demuth]() Charles Demuth

Charles Demuth -

![John Sloan]() John Sloan

John Sloan -

![Chaim Soutine]() Chaim Soutine

Chaim Soutine - Horace Pippin

-

![Alfred H. Barr, Jr.]() Alfred H. Barr, Jr.

Alfred H. Barr, Jr. ![Bertrand Russell]() Bertrand Russell

Bertrand Russell- Albert Einstein

- Thomas Mann

- Charles Laughton

-

![Historical African Art]() Historical African Art

Historical African Art -

![Impressionism]() Impressionism

Impressionism ![American Modernist Painting]() American Modernist Painting

American Modernist Painting

Useful Resources on Albert C. Barnes

- Art Held Hostage: The Battle over the Barnes CollectionOur PickBy John Anderson

- The Devil and Dr. Barnes: Portrait of an American Art CollectorOur PickBy Howard Greenfeld

- The Art in PaintingOur PickBy Albert C. Barnes

- The Art of CezanneBy Albert C. Barnes and Violette De Mazia

- The Art of Henri MatisseBy Albert C. Barnes and Violette De Mazia

- The Art of RenoirBy Albert C. Barnes and Violette De Mazia

Ask The Art Story AI

Ask The Art Story AI