Summary of Paul Éluard

Considered one of the founding fathers of Surrealism, Éluard was the most gifted of the movement's poets. A friend and influence of/on any number of the Parisian avant-garde, he produced a body of work that married poetic experimentation with a commitment to political activism. Though idealism blinkered him to some of the realities of life under communist rule, his belief in human freedoms was unyielding. His convictions saw him take up an active role with the French Resistance and he emerged from the war as a national hero. Having fallen in love and married three times, his seventy or so publications are adorned with a selection of moving love poems. He was, according to the Egyptian poet Georges Henein, "the bearer of tenderness" and his ultimate goal in life was always the same: to use words "to reduce the distances between people".

Accomplishments

- By the time André Breton published the first Surrealist Manifesto in 1924, Éluard and Max Ernst had already completed their second book collaboration (Les Malheurs des immortels). The two men had anticipated the incredulous playfulness of non-sequiturs and the strange, dream-like, imagery that would become the seal of the Surrealist movement.

- Éluard abandoned art for poetry early on is his career. He was, however, an enthusiastic collaborator who, with Breton, Valentine Hugo and Nusch Éluard, pioneered the Surrealist experiment of the "Exquisite Corpse". Though dismissed by some critics as no more than a parlour game (in which each participant "blindly" completes a section of a piecemeal image), it became a defining feature of Surrealist art and was valiantly defended by Breton as a way to "escape self-criticism and fully release the minds of metaphorical activity".

- Éluard most famous work was called Liberté, j'écris ton nom (Liberty, I Write your Name), written during the Nazi occupation of France. Its message of hope and freedom made Liberté one of the most important poems in modern French history when thousands of copies were dropped across France by the British air force. An active member of the French Resistance, the poem secured him the status of "national war hero". Liberté was later transformed into a "poème-objet" by Fernand Léger who married the text with his striking stencil technique.

- Éluard collaborated with the Catalan Surrealist Joan Miró on what would become a landmark event in publishing history. Eleven years in the making, and only completed by Miró after the poet's death, À toute épreuve was a project with no hierarchy between text and image. It was conceived of, in the words of Miró, as "a book [that has] all the dignity of a sculpture carved in marble" and only 20 copies were produced. It was in the words of the two men who produced it, a work of "plastic harmony".

The Life of Paul Éluard

Éluard dreamed of a world in which mankind would be as one: "even when we sleep we watch over each other, and this love heavier than a lake's rope fruit", he continued, was "without laughter or tears [and] lasts forever".

Paul Éluard and Important Artists and Artworks

Le Cirque Triptych (The Circus Triptych) (1913)

Although he is known as one of the most important figures in twentieth century poetry, Éluard produced a small number of drawings during his early years. By the early 1920s Éluard had decided that his writing was superior to his art and no more than a dozen artworks by him, all produced between 1910-18, are known to exist. In this grouping of abstract compositions, produced by an 18-year-old Éluard, strange and stylised organic shapes, boldly outlined in black - partly human, partly animal - float and tumble under the spotlights of a circus big top. Produced during his stay at a sanatorium in Clavadel, Switzerland, where he was recovering from tuberculosis, Éluard's crude and childlike crayon drawings have some resemblance to Kandinsky's abstractions.

The critic Piero Bisello said of the work, "It might have been inspired by a circus visit in the nearby Davos, or by photographs, or his childhood in Paris. It is formally very appealing and it reminds of later works by Miró: the variegated palette, the stylised and rounded depiction of living bodies in a flat environment typical of child scribbles, and the thick black outline of the figures. Moreover, there is a strong formal charge coming from [...] a roughness that doesn't merely remind [us] of the inexperience of the artist, but brings up an aesthetically interesting contrast between the neat marks and the blurry patches of colour".

Wax crayon on paper - Rosenberg & Co

Les Malheurs des immortels (Misfortunes of the Immortals) (1922)

In this strange, dream-like image, reminiscent of a nineteenth century wedding photograph, Ernst presents a formally-dressed male figure - with the head of an eagle - beside a seated woman, her face replaced by an inverted butterfly or moth. The towel draped over the birdman's arm suggests that he could be either a hairdresser or a waiter, while the snake provides the time-honoured symbol of the perils of temptation. The two friends collaborated on the creation of the poems, "playing like children at cutting and pasting and figuring out the world in order to remodel it", wrote French academic Sonia Assa.

Although André Breton's Surrealist Manifesto was yet to be published, Éluard and Ernst's second book collaboration, Les Malheurs des immortels (from which this image is taken) clearly presages the bizarre playfulness and interest in the subconscious of the movement to come. On each of the book's 20 double pages, there is a title, a poem and an Ernst collage. But, in a reversal of the conventional illustrated children's book, it is the poems that illustrate the image. As MoMA describes it on its website, "the book pairs the semantic dislocations of Éluard's poems with the visual disjunctions of Ernst's recent collages".

Assa adds, "turning the pages of Les Malheurs des immortels for the first time, we are struck by two obvious and competing impressions. One is the similarity of the collaborative work with sixteenth and seventeenth century emblem books. On each double-page there is a picture, a title, and a poem: each of the three components, though perhaps seemingly unrelated, is expected to contribute to the global 'meaning'. The other impression is of eeriness combined with playfulness, of determined nonsense prevailing in pictures and texts where non-sequiturs are the law. We find ourselves in the midst of a familiar world gone awry, in the dimension of the heteroclite".

Wood engraving

Portrait of Paul Éluard (1929)

This painting, considered one of the finest Surrealist portraits, unites two of the movement's most iconic figures: Dalí and Éluard. As Sotheby's described it in its auction catalogue, the "rich and complex symbolic imagery, along with its technical mastery [confirm] its importance as a document of this pivotal moment in the history of the Surrealist movement [and make it] impossible to resist the temptation to look for allusions to Gala [Éluard's then wife]".

Éluard sat for Dali during his 1928 stay at the painters home at Cadaques on the Spanish coast. Dali had become smitten with Gala and felt doubly frustrated; both at her marriage to the poet, and because of his own sexual inadequacies. Dali's secretary and biographer, Robert Descharnes, wrote: "Dalí felt flattered that Paul Eluard should have come to see him [and as] for Gala, she was a revelation - the revelation Dalí had been waiting for, indeed expecting. She was the personification of the woman in his childhood dreams to whom he had given the mythical name Galuchka".

Éluard's head floats like a helium balloon over a desolate landscape. Near the top, the head of a lion, often interpreted through Freudian dream symbolism as a statement of violence and raw desire, became a motif in Dali's paintings around this time. Meanwhile, also in the upper right of the composition, Dali represents a woman's face in the shape of an ewer which, in Freudian symbolism, likens the figure of the woman with that of a carrier or receptacle. The Sotheby's catalogue suggests that this "confrontation of the male and female symbols has been interpreted as the artist's neurotic apprehension of his relationship with Gala" and a further clue to this theme can be found in the image of the grasshopper. The insect held a personal meaning for the artist who as a child fantasized about being a "grasshopper boy", but the praying mantis was also a favorite symbol amongst Surrealists who were drawn to the idea of a male being devoured by the female, post-coitus. Additionally, the Éluards kept a collection of praying mantises, and, as the couple's guest, the artist had been able to observe the insect's behaviour first-hand. The portrait remained in the collection of Gala and Dalí until Gala's death in 1982 when it was given to Gala and Éluard's daughter, Cécile. The portrait sold for $22.4 million in 2011, setting the then new record for a Dalí painting.

Oil on cardboard - Dali Theatre and Museum, Figueres, Spain

Cadavre exquis (Exquisite Corpse) (c.1930)

This work, made up of seemingly disconnected symbols and motifs to form the shape of a human body, emerged from a favourite Surrealist parlour game. It involved passing a piece of paper round on which each of the participants would create a "body" consisting of a head, torso, arms, legs and feet, folding the paper over to hide their contributions before passing it on to the next player. The conflation of images points to the fundamental Surrealist notion of chance and automatism. In the abridged Surrealist dictionary (Dictionnaire abrégé du surréalisme) Breton wrote the following entry: "EXQUISITE CORPSE - A game in which several people compose a phrase or drawing together, folding the paper so that no one can see the previous collaboration or collaborations. The now-classic example, which gave the game its name, was the first phrase created in this method: the exquisite-corpse-drank-the new-wine".

The head of the body - drawn by Éluard's soon-to-be second wife, Nusch - is a pot out of which snakes appear; the neck and arms by Breton are musical symbols; the torso, by Hugo, is a landscape of trees and a waterfall. Éluard and Nusch were involved in drawing the bottom section in which their names appear among a succession of signs and symbols. These pieces were often ridiculed by the critics, but Breton defended the practice: "The malicious critics of the years 1925 to 1930 simultaneously complained that we were caught up in puerile games and suspected us of having individually (and laboriously) produced the game's 'monsters' in full sight - yet further proof of the critics' carelessness. What excited us about these games is that no single mind could have made what they created, and that they had a great deal of the power of drift, which poetry too often lacks. With the Exquisite Corpse we found a way - finally - to escape self-criticism and fully release the minds of metaphorical activity".

Graphite on paper - Collection of the Tate, United Kingdom

Portrait of Paul Éluard (1932)

Valentine Hugo made her first mark on the Parisian avant-garde in 1913 when a number of her ballet drawings graced the foyer of the Champs-Elysèes Theatre on the opening night of Stravinsky's scadalous The Rights of Spring ballet. She worked subsequently on the stage design for Jean Cocteau's ballet Maries de la Tour Eiffel, in 1921, and with her husband, Jean Hugo (the grandson of one of France's greatest writers, Victor Hugo), on his staging of Romeo and Juliet, in 1926.

Hugo became directly involved with the Surrealist elite in 1928 and contributed to a number of the group's Cadavre Exquis drawings. She also created surrealist assemblages of her own and, with Marie-Berthe Ernst, was the first woman to feature in a Surrealist exhibition, at the Galerie Pierre Colle in 1933. She continued to exhibit with the Surrealists up until the beginning of the Second World War. Hugo was also part of group behind Editions Surréalistes, a series of self-published books (many made from luxurious materials and available only through subscription) featuring surrealist "objects of passion" (dismissed by many outsiders as pornography). Hugo became renowned for her illustrative work and produced images for books by Victor Hugo, Breton, Rimbaud, Archim d'Arnim, as well as many for Éluard.

Hugo hosted a number of salons during which she would make sketches of her guests who included the likes of Breton, Picasso and Éluard. She would, at a later date, transform her sketches into full portraits. In this dense, verdant, image, somewhat reminiscent of an archetypal character card in a Tarot set, Hugo depicts Éluard in four profiles. Recalling her earlier set designs for Romeo and Juliet, the poet is made up of sinuous lines like wood grain that merge into a tree trunk that, in turn, doubles as the robe of a nymph or goddess. Having divorced Jean Hugo, she moved into the same building as Éluard and Breton (in May 1932). She engaged in a tumultuous affair with Breton which ended so badly that Hugo attempted suicide. Happily, she called Éluard just in time for him to save her life. The pair shared a close bond after this episode and she became the major illustrator of Éluard's books, complimenting his poems with a series of fine, fantastical line drawings. It is said that her drawing, Le Harfang des Neiges (the Snowy Owls) was hung above the poet's bed when he died in 1952.

Pastel on paper - Musée Fabre, Montpellier Méditeranée Métropole

Paul Éluard (1941)

According to the Musée Picasso website, Éluard was Picasso's best friend from 1935 until the poet's death. It records, "Following the disappearance of Apollinaire, Eluard was the only poet with who Picasso could converse and exchange or share ideas. Quickly, the surrealist poet became literally captivated by the demiurge-artist, 'who insists [on] seeing everything, on projecting onto the screen of man everything he can understand, admit or transform, figure and transfigure ... With Picasso, the walls come down'. Only Eluard's death, on 18 November 1952, would put an end to this brotherhood". Picasso's tender and fluid sketch of Éluard is an enduring record of what Musée Picasso heralds as a "sublime friendship".

Éluard was buried in the Père-Lachaise cemetery inside an area reserved for communists. The funeral (organised by the French Communist Party) was attended by Picasso and many others. The French government blocked the plan for a formal funeral procession to pass through the streets of Paris and so, Musée Picasso reports, "a multitude of friends, comrades and anonymous people gathered at the cemetery doors to pay their last tribute to the author of Liberté", adding that the funeral speeches "were given by Vercors (Jean Bruller), Louis Aragon, Laurent Casanova, André Delacour and Jean-Charles Gateau". Picasso, who was "visibly moved" was accompanied by Cécile Eluard and Russian-French writer Elsa Triolet. Musée Picasso describes how Picasso "stood watch over his friend's body and drew a dove with the inscription 'pour mon cher Paul Eluard" ('for my dear Paul Éluard')".

Black pencil on paper - Musée d'art et d'histoire Paul Éluard, Saint-Denis

Liberté, j'écris ton nom (Liberty, I Write your Name) (1953)

Éluard and Léger met and became friends after the Second World War. Both men were members of the Communist Party and Léger painted Éluard's portrait in 1947. In a reciprocal gesture, Éluard wrote the poems "Les constructeurs" and "A Fernand Léger" for Léger. In 1953, the year after the poet's death, Léger illustrated his concertina book Liberté, j'écris ton nom. Liberté was the first poem in the collection Poésie et vérité (1942) that Éluard had written it in the summer of 1941. He referred to it as a "poème de circonstance" ("a poem for a special occasion") because it gave vent to feelings of hope in the battle for freedom. The poem became exceptionally popular, with the word Liberté and the recurring line of verse "j'écris ton nom" ("I write your name"), stirring such strong feelings of patriotism and hope that the British Royal Air Force (RAF) dropped thousands of copies of the poem across occupied France. Liberté concludes:

"Upon the returned health

Upon the faded risk

Upon the hope without memory

I write your name

And for the power of a word

I restart my life

I was born to know you

To call you

FREEDOM"

Léger's book was designed to appeal to the widest public (especially to the working classes) and was conceived of thus in the design of brightly colored advertising banners. The book edition of the poem is that of a deluxe brochure with the "poème-objet" printed using a stencil art (pochoir) technique. Éluard's portrait dominates the front (and resembles the portrait painted by Léger in 1947). "All who gave to the Resistance in the fullest measure of their means cannot forget the large part played by ... Éluard in its organisation", wrote the French poet, Louis Parrot. Éluard "gave himself to it completely; at the same time that he was writing poems whose publication contributed immeasurably to the spiritual resurrection of France, he helped in rallying a great number of young writers".

À toute épreuve (Foolproof) (1958)

The Catalan surrealist Miró had developed his language of signs and symbols through his contact with the Paris Surrealist group during the 1920s. In Miró's art, the realms of the unconscious are expressed through amorphous abstract imagery and in the 1940s and 1950s, he applied his art increasingly to book illustration. He created landmark publications, most notably his illustrated collection of Éluard's poetry which is considered the high watermark of Miró's career as an illustrator. Éluard had written À toute épreuve at the time of the breakdown of his marriage to Gala, and though originally printed on four folded pages in the form of a leaflet, Éluard and Miró re-imagined it as an entirely new object. For Miró "Poetry and painting are done in the same way you make love; it's an exchange of blood, a total embrace - without caution, without any thought of protecting yourself" and within this fertile mood of collaboration, Éluard re-distributed the lines of his poems, leaving white spaces for Miró to embellish.

The publisher, Gérald Cramer, had approached Miró with the idea of illustrating Éluard's poems in 1947. In accepting the project, Miró told Cramer "I have made some trials which have allowed me to see what it was to make a book and not merely to illustrate it. Illustration is always a secondary matter. The important thing is that a book have all the dignity of a sculpture carved in marble". Miró's undertaking was vast. Over an eleven year period, he created 233 blocks to create 79 woodcut prints and incorporated found materials including wire, wood and a variety of papers to create a selection of multi-textured collages. Miró told Cramer "I am completely absorbed by the damn book [and] I hope to create something sensational, the most important achievements in engraving since Gaugin".

Meltem Sahin, curator at the Norman Rockwell Museum, writes: "In contrast to the depressed and pessimistic words of Eluard, Miro's illustrations [...] are optimistic [...] There is no hierarchy between words and lines. Because they share the same significance, the spectator is drawn from words to images simultaneously". Sahin adds that in Miró's illustrations we have "a celebration of love, joy and playfulness [that] can be observed through his usage of vigorous colors and buoyant figures [...] Only 20 copies were published with a premier edition, including additional woodcut prints of Miro". Sahin concludes that À Toute Épreuve "is a masterpiece in the history of Modern Illustrated Books that emerged from the duet of the two geniuses, in their own words, a masterpiece of 'Plastic harmony'".

Biography of Paul Éluard

Childhood and Education

Eugène Émile Paul Grindel - later known as Paul Éluard, having taken the maiden name of his maternal grandmother - was the only child of a Real Estate Agent and bookkeeper, and a seamstress. The family moved from Saint Denis to the 10th Arrondissement in Paris when Émile was 13. He attended a local school where he won a scholarship to attend the École Supérieure de Colbert. Éluard was, by his own admission, an unexceptional student but he did excel at English and spent some time in England as a teenager.

Éluard contracted tuberculosis at the age of 16 and was sent to recover at a sanatorium near Davos, Switzerland. He spent eighteen months at the sanatorium during which time he began reading the works of symbolist and avant-garde poets including Arthur Rimbaud, Charles Baudelaire, Guillaume Apollinaire, and Walt Whitman, whose Leaves of Grass he claimed to have read repeatedly. At the sanatorium, he entered into an intense relationship with a young Russian patient, Elena Diakonova. It was she who introduced the Frenchman to the works of the great Russian authors Leo Tolstoy and Fyodor Dostoyevsky. Éluard gave Elena the nickname of Gala and described her as "the woman whose gaze pierces walls". Éluard's love for Gala further fuelled his ambitions to become a poet and she assumed the role of his muse. By April 1914, however, Émile and Elena were fit enough to be returned to their respective homes in Paris and Moscow and were temporarily parted.

Éluard joined France's war effort as a medic and infantryman. Following a near fatal gas attack, however, he spent most of 1915 in hospital suffering a range of ailments, including bronchitis, cerebral anaemia, and even a chronic appendicitis. The following year, he worked in an auxiliary capacity at a military evacuation hospital, just 10 kilometres from the war front. His job involved writing letters to the families of the dead and wounded while at night he dug graves.

Éluard pined for Gala and was determined to marry her. His mother gradually warmed to their relationship although his father was not easily won over. Nevertheless, Gala was able to convince Gala's stepfather to allow her to study French at the Sorbonne (in Paris) and the couple married while Éluard was on leave from the army in February 1917. To both families' dismay, Éluard immediately announced he was going back to the front line two days after the ceremony. A month later he was hospitalised once more, this time with incipient pleurisy. Good news followed, however, when Gala gave birth to their only child, Cécile, in May 1918.

Mature Period

During the War, Éluard published, at his own expense, his first two volumes of poetry, Le Devoir et l'Inquiétude (Duty and Anxiety) in 1917 and Poèmes pour la Paix (Little Poems of Peace) in 1918. Gala helped him to prepare covering letters to literary figures who had taken a fierce stand against the War. Encouraged by Gala, Éluard introduced himself to three writers - André Breton, Philippe Soupault, and Louis Aragon - who would help shape his future career. They had launched a new avant-garde journal, Littérature, which was destined to become the main channel for the development of Surrealism in the early 1920s. Breton recalled later how a nervous young man (Éluard) had approached him at the theater, calling him by an unfamiliar name, before explaining that he had mistaken Breton for a friend missing in the war. When Éluard eventually went to visit Breton to share his poetry, Breton realised that Éluard was in fact the nervous young man who had approached him at the theater.

Breton and his friends were impressed with the originality and technique of Éluard's poetry. Éluard was a natural fit for the group; sharing with them a disdain for the prevailing political and social order and its military complexes. They determined to create an art form that could express their feelings about their massacred friends and the oppressed and coerced youth of France. Indeed, youth became a motif in Éluard's poetry which "exploded the myth" of youth equalling innocence and purity. He would use the phrase "enfants sans âge" ("children without age") and described the psychology of youth as "l'état heureux, sans passé, sans souvenir" ("the happy state, without past, without memory").

The men were initially drawn to the Dada movement which had originated in Zurich, Switzerland as a reaction against the War and the heightened mood of nationalism. The "automatic writing" of Dada poetry resulted from allowing the mind to follow illogical and irrational impulses, which, in turn, gave rise to the "absurd" use language. Éluard sent his poems to one of Dada's founding figures, Tristan Tzara, and in January 1920 the pair met in the Parisian apartment of the painter Francis Picabia. The new group set up the first French Dada performance in Paris on March 27, 1920. Appearing alongside Gala, and dressed in drag, Éluard made his stage debut in a play written by Breton and Soupaul. He later returned to the stage as a village idiot wrapped in a paper bag, reciting a nonsensical text by Tzara and, in another performance, Éluard appeared in an engine cylinder.

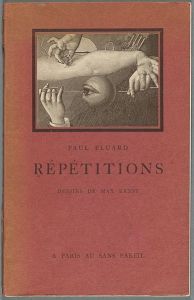

The group soon became ambivalent towards Dada which had failed to make much of an impact on a seemingly unshockable post-war Parisian audiences. Breton wanted to endow the movement with a more overt political agenda; Soupault fell in love and married; Aragon returned to his medical studies; and Éluard and Gala left Paris for Monte Carlo where they gambled large amounts of money away. The couple moved onto Tunisia where they bought a chameleon which they brought back with them to their Parisian home. During 1921 the couple expanded their circle of avant-garde friends (which included Man Ray who was newly arrived in Paris) and Éluard produced what is thought to be his earliest Surrealist statement in verse: "Les Nécessités de la vie et les conséquences des rêves" ("Life's necessities and the consequences of dreams"). In November of that year Éluard and Gala visited the German Dadaist Max Ernst in Cologne. Éluard bought two of Ernst's paintings and chose six collages to illustrate his poetry collection, Répétitions (Repetitions).

In 1922 the two men collaborated on Les malheurs des immortels (The misfortunes of the immortals) and the following summer, the Éluards holidayed in the Austrian ski resort of Tyrol with Ernst, his wife and their son. Soon after, Ernst, who had begun an affair with Gala, moved out of his family's apartment. Unable to secure the necessary papers to leave Germany, Ernst entered France illegally and settled into a ménage à trois with Éluard and Gala. When asked about the situation, Éluard declared, "I love Max Ernst more than I love Gala". Ernst made himself at home by decorating the Éluards' home with murals.

After a time, Éluard found his personal situation untenable and sought refuge in bars and night clubs where he drank to excess. In March 1924, Éluard met with Aragon in a local café and shared with him his domestic woes. Éluard left the café on the pretext of buying a box of matches and failed to return. The next day Éluard cabled his father, asking him to tell everyone that he had had a haemorrhage and had been moved to a clinic in Switzerland. The truth of the matter was that Éluard had traveled to Marseilles from where he sailed on a vessel bound for French Polynesia. From there he wrote to Gala, urging her to sell their art collection - which included works by Picabia, Ernst, Pablo Picasso, Georges Braque, Giorgio de Chirico, Juan Gris, André Derain and Marie Laurencin, as well as African masks and other objet d' art - and to join him. Gala was able to reimburse the money they owed Éluard's father and set off with Ernst to meet Éluard, who was by now in the French colony of Saigon, Vietnam. There, the trio decided that Gala would end her relationship with Ernst and she returned to Paris with her husband (Éluard and Ernst remained devoted friends).

By October 1924 two rival Surrealist groups were vying for supremacy. One was more attuned to the irrational elements of Dadaism; the other, larger, group was led by Breton and carried a stronger mission for political and social change and aligned itself with the ideology of communism and anarchism. Éluard, with Aragon, Breton, and other associates, joined the French Communist Party. They explained their beliefs - "working for the liberation of man" - in a joint publication Au grand jour ("In broad daylight"). Éluard was a signatory to Breton's Surrealist Manifesto and also edited the reviews Surrealist Revolution and Surrealism at the Service of the Revolution. In his poetry, meanwhile, Éluard was experimenting with new techniques that explored the relationship between dreams and reality, and the free expression of thought processes. In 1926 he published his celebrated collection Capitale de la douleur (Capital of pain) - a collection that cemented his reputation - followed three years later by L'Amour la Poésie (Love, Poetry). A further collection, La Rose publique (The Public Rose), was published in 1934 and contains what many considered to be the "most Surrealistic" of all Éluard's efforts.

Salvador Dalí was in Paris working with Luis Buñuel on the filming of Un Chien Andalou (1929) when he first met Éluard. The two men became friends but Gala, who would soon leave Éluard for Dali, had initially taken a dislike to the Spaniard on grounds of his eccentric dandyism. Nevertheless, the Éluards, with Buñuel, and René Magritte and his wife, accepted Dali's invitation to join him at his Spanish home in Cadaqués in the summer of 1928. Dali's biographer, Robert Descharnes, wrote: "During the summer, Dalí and Gala took long walks along the cliffs near Cadaqués; Dalí fell madly in love with Gala, who would become his legendary, life-long companion and muse. At the end of her stay, Dalí saw Gala off at the station in Figueras, where she took a train to Paris. Then he retired to his studio and resumed his ascetic life, completing the Portrait of Paul Eluard which the writer had been sitting for".

In 1930, Dalí provided the frontispiece for Éluard and Breton's collection, The Immaculate Conception, a series of poems in prose, in which they communed with the vegetative life of the foetus and simulated demented states, as well as provocatively undermined Christian notions such as the virgin birth. Later in the year (November 1930) Luis Buñuel's scandalous "anti-Catholic/anti-bourgeois" film L'Age d'or (the film had been co-written with Dali who abandoned the project at the writing stage because of Buñuel's anti-Catholic sentiment) was shown publicly (with the sanction of a "censorship visa") at the Studio 28 cinema in Paris. A film about unbridled passion struggling against state and church oppression, it was immediately condemned by the Italian Embassy, who believed Buñuel had caricatured high ranking figures in the Vatican, and the League of Patriots and the Anti-Jewish League, who sprayed the screen with ink, threw smoke bombs and slashing works by Arp, Dali, Ernst, Miro, Man Ray and Tanguy that were on display in the reception area. The film was quickly banned on grounds that it was blasphemous and pornographic. Responding to the ban, Éluard wrote: "the passage from pessimism to the state of action is determined by Love, the principle of evil in bourgeois demonology, which demands that we sacrifice everything (situation, family, honor) to it, but whose failure in social organization introduces the feeling of revolt". (L'Age d'or remined banned in France until 1981 when an original print was fully restored by the Center Pompidou.)

In 1933, Éluard was expelled from the Communist Party partly because of an article by Ferdinand Alquié published in Surrealism at the Service of the Revolution - which he edited - denouncing the in Soviet films (Stalin having banned the avant-garde Constructivism movement in the mid-to-late 1920s).

Éluard had been introduced to Maria "Nusch" Benz, a destitute music-hall performer, circus acrobat and hypnotist's stooge, in 1929. Light-hearted and graceful, Nusch (11 years Éluard's junior) became his perfect companion, inspiring some of his tenderest romantic poems. Shortly after their marriage in 1934, Éluard published a book entitled Facile (Easy), which brought together Éluard's love poems with eleven photographs by Man Ray of Nusch's body. These photographs gave rise to the term photopoème; a term coined by the French academic, Nicole Boulestreau, as a way of describing a way in which "meaning progresses in accordance with the reciprocity of writing and figures".

Around the same time, Éluard became firm friends with Pablo Picasso: "You hold the flame between your fingers and paint like a fire", Éluard wrote to the Spaniard. The 1936 collection Les yeux fertiles (Fertile eyes) was written by Éluard as a celebration of their friendship. Around this time Éluard introduced his friend to the Surrealist photographer Henriette Theodora Markovitch, better known as Dora Maar. Picasso and Maar became lovers and it is she who is often credited with inspiring his politicized art. Indeed, Éluard, Picasso and Maar were horrified by at the rise of Fascism in Europe, Franco's "seize on Madrid" and the bombing of the Basque town of Guernica in 1937. Éluard wrote what is thought to be his first overtly political poem, "November 1936", which was published in L'Humanité in December 1936. That poem inspired Picasso to produce the prints of the Dream and Lie of Franco, in January 1937, and in the same year Éluard penned Victory of Guernica, which inspired Picasso to paint his famous masterpiece. In 1938, "November 1936" would be published in the form of a book entitled, Solidarité, in which the text was illustrated by etchings by various artists.

By 1938, Éluard had broken with Breton whose approach to Surrealism had started to repel him. Rather, he developed his own idea of human brotherhood in which women were viewed as spiritual mediators. Le livre ouvert I (The open book 1) of 1940 was one of the first collections in which Éluard effectively denounced what he saw as the self-indulgences of the Surrealists. "What Éluard wrote during the trying years," wrote the Surrealism scholar Anna Balakian, could "fall into two groups: the directly circumstantial verse representing the basic color of events and his subtler interpretations of disaster".

In 1942, with France under Nazi occupation, Éluard re-joined the (now illegal) French Communist Party; "a move which seemed a natural corollary to resistance, and to which he was drawn by his intensely human feeling for the solidarity of mankind", observed French literature scholar Geoffrey Brereton. "What attracted him was the theoretical purity of the doctrine", Brereton continued, he "idealised fraternity [and his] belief in it was a simple extension of his feelings for the human individual". The tyranny of Nazi occupation reinforced Éluard's optimism and determination, and he was an active member of the French Resistance, using the pseudonyms Jean du Hault and Maurice Hervent, to deliver secret papers and assist in the publication of clandestine literature. His "Poésie et Vérité" ("Poetry and Truth") of 1942 was denounced by the Germans and Éluard and Nusch were forced to move to a different residence every month. Fleeing the Gestapo, Éluard took refuge in a mental asylum at Saint-Alban, where many resistance fighters and Jews were in hiding. There he became deeply affected by the misery of its inmates and was inspired to write "Souvenirs de la Maison des Fous" ("Souvenirs from the House of Fools") in 1943.

Éluard's most famous poem Liberté proclaims the "power of a word" by which the poet can begin his life afresh: "I was born to know you / To name you / Liberty". Thousands of copies of Liberté were dropped from British aircraft over France. Éluard also gathered the texts of several poets of the Resistance for an anthology, L'Honneur des poètes (The Honor of Poets). The collection had a powerful effect on French morale too. In June 1944, he created L'Eternelle Revue, for which he proposed to gather around himself the best young writers and after the War, Éluard and Aragon were hailed as the great poets of the Resistance. A five-poem collection, Poésie Ininterrompue (Uninterrupted Poetry), was published in 1946, as was Le Dur Désir de Durer (The Strong Desire to Endure), which was illustrated by Marc Chagall.

Late Period and Death

Éluard's health continued to trouble him, and he often left Nusch in Paris while he recuperated in the mountains or by the sea. But on November 28, 1946, while staying in Switzerland, he learned of Nusch's sudden death from a brain haemorrhage. Her unexpected passing rendered Éluard suicidal. It took him three years to shake off his despair.

After the war Éluard remained active in the international Communist movement. He traveled in Albania, Britain, Belgium, Czechoslovakia, Mexico, and Russia, but not the United States which refused visas to known Communists. His passion for peace, and an idealism that blinded him to the reality of life in the Soviet Union, led him to write in admiration of Stalin. But following Nusch's death he abandoned his political writing, producing Le Temps Déborde (Time is running out) and De l'horizon à l'horizon de tous (From the horizon to everyone's horizon) which traced his grief at the premature death of Nusch and his journey from suicidal despair to hope.

With Picasso, Éluard took part in the World Congress of Intellectuals for Peace in Wroclaw, Poland, in 1948. Addressing an audience in Bucharest he said, "I come from a country where no-one laughs any more, where no-one sings. France is in shadow. But you have discovered the sunshine of Happiness". In April 1949, he was a delegate to the Council for World Peace and in June of the same year, he spent a few days with Greek partisans in the Gramos Hills fighting against government soldiers. He proceeded to Budapest where he attended the commemorative celebrations of the centenary of the death of the poet Sándor Petőfi, and meeting the renowned Chilean poet Pablo Neruda. By September, Éluard was in Mexico for another peace conference. There he met Dominique Lemort, with whom he returned to France. They married in 1951 and published "Le Phénix" ("The Phoenix"), which celebrated his rediscovered happiness. It was to be, sadly, a rather short lived happiness. Éluard died aged just 56 a year later with Dominique at his bedside.

The Legacy of Paul Éluard

The artists with whom Éluard collaborated reads like a roll-call of twentieth century giants. Ernst, Dalí, Man Ray, Picasso, Chagall, de Chirico, Léger and Miró were all inspired by Éluard's writing and produced many illustrations for books of his poetry. René Magritte felt a deep affinity with Éluard's work. He was first captivated by a single line of poetry written for Gala, "The darkest eyes enclose the lightest". In 1954, the sculptor Ossip Zadkine created a Surrealist sculpture, The Poet or Homage to Paul Éluard for Paris's Luxembourg Gardens, inscribed verses by Éluard.

Éluard's writing also inspired poets around the world throughout the ensuing decades: the Bengali Bishnu Dey, the Iranian Mahmud Kianush, the Greek Odysseus Elytis amongst others. The French composer Francis Poulenc considered turning poems into songs as an act of love and set his finest melodies to texts by Éluard, writing Cinq poèmes de Paul Éluard in 1935. Bonjour Tristesse ("Hello Sadness"), Françoise Sagan's 1954 novel, takes its title from Éluard's poem, "À peine défigurée" ("Barely disfigured"), which begins with the lines "Adieu tristesse/Bonjour tristesse..." ("Farewell sadness, Hello sadness"). In film, meanwhile, Éluard's poems are used throughout the great French auteur Jean-Luc Godard's 1965 science fiction/noir Alphaville. Éluard would have seen this as a fitting tribute since in Godard's totalitarian vision of the future, Éluard's poetry is the only portal to love and freedom.

Influences and Connections

-

![Guillaume Apollinaire]() Guillaume Apollinaire

Guillaume Apollinaire -

![Arthur Rimbaud]() Arthur Rimbaud

Arthur Rimbaud ![Walt Whitman]() Walt Whitman

Walt Whitman- Fyodor Dostoevsky

- Leo Tolstoy

-

![Dada]() Dada

Dada -

![Surrealism]() Surrealism

Surrealism ![Communism]() Communism

Communism

-

![Fernand Léger]() Fernand Léger

Fernand Léger -

![René Magritte]() René Magritte

René Magritte -

![Joan Miró]() Joan Miró

Joan Miró ![Ossip Zadkine]() Ossip Zadkine

Ossip Zadkine- Francois Poulenc

-

![Pablo Picasso]() Pablo Picasso

Pablo Picasso - Jean Hugo

- Valentine Hugo

Useful Resources on Paul Éluard

- In Montparnasse: The Emergence of Surrealism in Paris, from Duchamp to DalíBy Sue Roe

- Dalí de Gala (Lausanne, 1962)By Robert Descharnes

- Salvador Dalí, (New York, 1976)By Robert Descharnes

Ask The Art Story AI

Ask The Art Story AI