Summary of Japonism

Depicting the world through an alternate lens from the Western Renaissance, the introduction of Japanese art and design to Europe brought about revolutions in composition, palette, and perspectival space. Japonism, also often referred to by the French term, japonisme, refers to the incorporation of either iconography or concepts of Japanese art into European art and design. It is important to note that this integration was often based on European notions of Japanese culture as much as authentic influence. Most of the Impressionist and Neo-Impressionist artists, as well as the members of the Aesthetic movement, were deeply influenced by this new approach to representation.

Key Ideas & Accomplishments

- As Japan began trade with Europe, the aesthetic and philosophies of Japanese design quickly became fashionable. European collectors amassed both high-end objets d'art and inexpensive prints (which were actually originally included as packing material for fragile luxury goods).

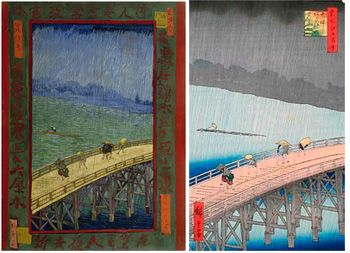

- Artists seeking a fresh alternative to the Renaissance tradition of illusionistic painting were drawn to the vivid colors and new perspectives of Ukiyo-e Japanese woodblock prints. While these images remained realistic, their simplified palettes, unusual viewpoints, minimalistic arrangements, and flattened space inspired European painters to experiment with their compositions.

- Studying Japanese prints, painters began to experiment with new ideas of perspective. They copied the common juxtapositions of objects near and far, along with unconventional cropping to create less symmetrical and more engaging compositions. This, combined with bright patterns of juxtaposed colors, often rendered in flat planes reminiscent of woodblock prints, created a flattening effect that became central to modernist painting.

- The appeal of Japonism was paradoxical: it was both appreciated for its exoticism and quickly assimilated as the organic expression of Western artistic ideals. Elements of the Japanese style were considered to express French and British sensibilities, even when they remained identifiable as Asian influences.

Artworks and Artists of Japonism

Portrait of Émile Zola

What appears to be a casual portrait of the writer Émile Zola is really a carefully composed array of symbols and references. Zola is shown in Manet's studio, but the objects around him were chosen to suggest Zola's character and convey the friendship between the artist and the sitter. When Manet's Olympia had scandalized the 1865 Salon, Zola, a respected art critic, published a brochure (1866) to defend Manet's work; that essay is clearly visible on the desk. In it, Zola argued that Olympia was Manet's best work, and it was due to his ardent support that Manet offered to paint this portrait. The men are shown as comrades in the battle for modern art, hinted at by the juxtaposition of reproductions of Manet's Olympia with Utagawa Kunaiki II's print of a wrestler. Zola sits in profile, looking up from the open book with a thoughtful expression. The text is likely Charles Blanc's L'Histoire des peintres (1861), a book which Manet often consulted, further linking these two men.

Other objects in the room also point to their shared tastes and artistic influences. On the left, a Japanese screen depicting a landscape and a bird on a branch, is partially visible. Manet, however, doesn't simply import these exotic objects into the portrait, he incorporates elements of japoniste design into the composition. The lines of the gray screen and the white border of the Japanese print on the right transform the black background into a series of intersecting rectangles. This creates a flat pictorial plane that contrasts sharply with the writer's head and shoulders before merging with the almost solid form of his black jacket. This effect is strikingly similar to the figure of the wrestler in the Japanese print, who is also strongly outlined by his black long coat. Thus, the elements of Japonism are included not only to convey the shared interests of Manet and Zola, but as a means of flattening and simplifying the shapes and palette to create a new, modern style of Western portraiture.

Oil on canvas - Musée d'Orsay, Paris

Sideboard

This sideboard, made of ebonized mahogany, exemplifies Godwin's Anglo-Japanese style. While it remains a functional piece of furniture, the form has been abstracted and ornamented to create a visually intricate series of rectangular shapes. Adopting elements of Japanese design, Godwin arranges the cubic cabinets on top of the table so that they call attention to the negative space surrounding them. The process of ebonizing the wood made it more uniform in color and texture, allowing the viewer to focus on its structure. It seems almost metallic in its perfection, the smooth lines interrupted only by selective decoration and the silver-plated handles. With its geometric forms and austere lines and material, the work prefigures the modernism of Dde Stijl and the Bauhaus.

Godwin began his career as an architect and designer working in the mid-century Victorian Gothic style. Through his association with Whistler, for whom he built The White House (1877-1878), Godwin began studying Japanese design and became a pioneer of the Anglo-Japanese style. His luxurious furniture and architectural spaces were also closely allied with the Aesthetic Movement.

Mahogany, ebonized, with silver-plated handles and inset panels of embossed leather paper - Victoria and Albert Museum, London

Harmony in Blue and Gold: The Peacock Room

This multi-media installation was designed to display Frederick R. Leyland's prominent collection of Chinese porcelain. A wealthy shipping magnate, Leyland had commissioned Whistler to only paint a portrait of the renowned beauty, Christine Spartall, to decorate his dining room. When the architect in charge of the larger project, Thomas Jeckyll, became ill, Whistler took it upon himself to complete the decoration of the room. Although Leyland was pleased with the design, the unapproved and expensive project (some estimated $200,000 above budget) led to a falling-out between artist and patron. As an entire environment, however, the Peacock Room is a masterpiece; it was purchased by Charles Freer and is installed today at the Smithsonian Museum.

This view of The Peacock Room shows Whistler's Rose and Silver: The Princess from the Land of Porcelain (1863-64), in a gold frame and framed by golden shelves. Nestled amongst the intricate geometry of this display, the painting is also japoniste in iconography and composition. In its subject, it directly reflects the influence of Kitagawa Utamaro, most known for his prints of beautiful women. Holding a Japanese fan in her right hand and dressed in a floral kimono, the beauty stands pensively on a blue and white patterned rug, in front of a byobu (Japanese screen).

In designing the room, Whistler took his painting as the central motif, for instance, adding a blue and white rug similar to the one in his portrait. At the same time, the portrait is enriched by its placement, as the rose of the kimono takes on a golden hue from its surroundings. The painting and its environment are built to be considered as one unity.

In the 20th century, Whistler's all-encompassing design would influence Abstract Expressionists such as Robert Motherwell and David Smith. A more contemporary interpretation of the room was Darren Waterston's installation Filthy Lucre (2013-2014), which recreated the opulent room in a state of decaying ruin, shelves overturned, vases broken, its gold oozing down the walls.

Oil paint and gold leaf on canvas, leather, and wood - Freer Gallery of Art, Washington DC

Dancers in the Rehearsal Room

This unusually elongated, horizontal canvas is further made strange by its unconventional composition. The left half is dominated by a blank diagonal wall, while a series of dancers are crowded into the remaining space. The viewer is further disoriented by the strange pose of the central figure, a young dancer who bends in half. As she stretches in this awkward position, her tulle creates a lacy white circle around her. Behind her, another ballet dancer stands in profile, and a third dancer, her skirt and arm flaring out, is partially visible. In the upper right, a flurry of partially visible dancers can be seen.

Unlike other artists who included Japanese props or clothing in their paintings, Degas avoids all obvious reference to Japonism. Yet this painting, and many of his depictions of 19th-century Paris are deeply infused with what he considered to be Japanese principles of composition and perspective. The elongated canvas, the emphasis on the asymmetrical diagonals of the wall, the large color planes, and the use of aerial perspective, all reflect the influence of ukiyo-e prints. The pose of the ballet dancer bending over is directly borrowed from Hokusai who often depicted his figures caught in movement. Degas adopted this approach to figurative poses to create a greater sense of spontaneity and instantaneity, ideas that were central to his Impressionist style.

Oil on canvas - The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, New York

Portrait of Père Tanguy (Father Tanguy)

When van Gogh arrived in Paris, the self-taught artist set to studying both Impressionist painting and Japanese prints. Both sources quickly became incorporated in his personal style, as demonstrated by this portrait of Julien-François Tanguy, an art dealer and owner of an art supplies shop who was affectionately known as Père Tanguy. Painted with highly visible brushstrokes and brilliant colors, Tanguy appears before a background of Japanese woodblock prints. The pure and contrasting complementary colors and flat picture space of his Neo-Impressionism are indented to both Impressionism and Japanese art.

Not only does van Gogh's portrait reveal his own interest in these influences, but he uses Japonism to conveys the character of Tanguy who appears as an introspective sage. Indeed, the stability of this generous supporter (who often accepted paintings in exchange for supplies) is implied by van Gogh's blending of Tanguy's hat with the print of Mt. Fuji behind him. Flattening the body of his sitter with strong outlines and brushwork, Tanguy appears to merge into the center of these vivid, yet harmonious juxtapositions of colors and images. The Japanese prints do not convey a sense of the exotic or mere visual interest, they are used to convey the honor and respect van Gogh felt for his friend. One of a series of three portraits, Tanguy kept this work in his personal collection until his death (when it was purchased by Auguste Rodin).

Van Gogh preferred to use the term "Japonaiserie" to describe the inclusion of Japanese art and methods into his work. He had first encountered ukiyo-e when he was still living in Antwerp; when he moved to Paris in 1886, he began collecting the prints along with his brother, Theo. The prints in the background are some of the Japanese prints that both brothers had collected (and van Gogh's La courtisane (The Courtesan) (1887) copied Keisai Eisen's print seen on the lower right of the canvas).

Prone to mythologizing Japanese culture, van Gogh idealized Japanese life and artists. He imagined them working as monks in a communal setting, hoping to recreate this atmosphere in the Yellow House, where he briefly lived with Paul Gauguin in 1888. Quite tellingly, van Gogh wrote to Theo, "Look, we love Japanese painting, we've experienced its influence - all the Impressionists have that in common - [so why not go to Japan], in other words, to what is the equivalent of Japan, the south? So I believe that the future of the new art still lies in the south after all."

Oil on canvas - Musée Rodin, Paris, France

Still Life with Japanese Woodcut

Gauguin's interest in non-Western cultures included elements of Japonism, both in the iconography of his paintings and their structure. This still life of two floral arrangements includes Utagawa Toskiiu's print, depicting Ichikawa Kodajki, a famous actor, in his role as the white-haired, spear bearing hunter, Nagohe. But Gauguin has also adopted the simplified color palette, absence of depth and shadow, and the division of the pictorial plane into several broad areas found in Japanese prints, creating a pictorial minimalism and flatness that pushes his still life away from the illusionistic tradition of the genre. The leaves along the border further suggest that the work is not trying to create an illusionistic depth but signals that it is in fact only a flat painted surface, vibrant with color.

In selecting these objects, the work exemplifies how Japonism informed Gauguin's development of Symbolism and Synthecism, two movements where he played a major role. The jug is Gauguin's own sculpture, Jug in the Form of a Head, Self-portrait (1889). It seems to gaze at the other vase of flowers, as does Nagohe, creating a humorous portrait effect. Gauguin sets himself as an equal to the Japanese artist. He chooses elements that become symbols, here, juxtaposing nature with his self-portrait, exotic culture, and art.

Oil on canvas - Tehran Museum of Contemporary Art, Tehran, Iran

Maternal Caress

In 1890, after seeing the ukiyo-e prints at the École des Beaux-Arts in Paris, Cassatt began work on a series of ten color etchings, including this one, inspired by Kitagawa Utamaro's prints of ordinary moments in women's lives, such as Midnight: Mother and Sleepy Child (1790). Finding an analogue to her own paintings of domestic spaces, Cassatt explored the composition and flatness of the print medium. This work, with its empty foreground and simple background rendered in broad planes of color, emphasizes the figure of a young mother. The pattern of her white patterned and floral chair (a pattern continued in the wallpaper) contrast with the nude child she embraces, creating a play between two- and three-dimensional forms.

This compression of space is further emphasized by the cropping of the image, which limits the view to a series of repeating patterns. As a result, line and color become a focal point, underscoring the intimate relationship of mother and child. The curving outlines of the two figures in the chair, coupled with the variations of the limited color palette create a sense of harmony. Cassatt's subsequent masterpiece, The Child's Bath (1893) echoed this flattened pictorial space, limited palette, and emphasis on pattern to become nearly abstract in its geometry, demonstrating the importance of Japonism to her style.

Drypoint, aquatint and soft ground etching, printed in color from three plates - The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, New York

Divan Japonais

Commissioned by the owner of the popular Montmartre dance hall, Le Divan Japonais, this lithographic poster celebrated the club's 1893 renovation in the Japanese style. In his advertisement, however, Toulouse-Lautrec focuses not on the trendy new décor of the hall, but rather the fashionability of its identifiable clientele. Jane Avril, a famous cancan dancer, appears at the center, watching a performance by Toulouse-Lautrec's favorite singer, Yvette Guilbert (the performer is recognizable by her characteristic long black gloves). The art critic Édouard Dujardin lingers in the background, his cane mirroring the delicate curve of a golden chair back.

Except for the title, which repeats the name of the hall, the work makes no obvious references to Japanese art, but rather draws upon its principles to invent modern graphic design. The Japonism of the new club is expressed through the style of the poster itself. This recreates the atmosphere by simulating aspects of Japanese prints, including the strong silhouettes, pictorial flatness, limited color palette, and asymmetrical diagonals of the composition. Like many popular Japanese prints, the subjects are famous courtesans, actors, and other celebrities, depicted with exaggerated expressions and body language. Toulouse-Lautrec sharply conveys the character of the place and the attitudes of its denizens, and at the same time elevates advertising to a fine art.

Toulouse-Lautrec's work is an enduring influence in graphic design, but it was also important to the avant-garde in its contemporary subject matter that erased boundaries between high and low art. Pablo Picasso was particularly influenced by his work, drawn to its raw energy, its louche subjects, and its bold composition. It also prefigures Pop Art with its emphasis on celebrity.

Lithograph printed in four colors, woven paper - The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, New York

Design for the Frederick C. Robie Residence

This private residence famously exemplifies Wright's influential Prairie School style with its bands of windows, strong horizontal lines, hipped pyramidal roofs, and a large rectangular fireplace. Although the horizontals do suggest the broad expanse of prairie marked by the horizon, the design was deeply influenced by Wright's study of Japanese design, a lifelong preoccupation.

First encountering Japanese architecture in Chicago at the Phoenix Pavilion of the1893 World's Columbian Exposition, Wright became enamored of Japanese art and design. Travelling to Japan in 1905, he bought hundreds of Japanese prints (even becoming a noted dealer in ukiyo-e) and he often included elements of Japanese print design in his architectural sketches. More fundamental, however, was his research into the philosophy of Japanese architecture, particularly in the relationships between exterior and interior spaces and the simplification of forms. As he said, "At last I had found one country on earth where simplicity, as nature, is supreme."

Pencil and ink on paper - Collection of the Frank Lloyd Wright Trust , Chicago, Illinois

Lady with Fan

In this example, Klimt's iconic portrayals of beautiful women makes explicit a Japanese influence in the woman's kimono and open fan.

Klimt was influenced by Japanese prints; his early graphic work, Fish Blood (1897-98), reflects their cropped composition, linear outline of form, and eroticism. The Rinpa school was also important to his creation of highly stylized and decorative portraits. For example, Klimt's work is not unlike Ogata Kōrin's Red and White Plum Blossoms (early-18th century) in its use of a gold foil-like background, arabesque lines, curvilinear patterns, and flower imagery. Yet, Klimt's Japonism is somewhat diluted, as we move into the 20th-century: the dragons are a borrowed Chinese motif, and Byzantine mosaics also inspired his use of gold backgrounds.

Oil on canvas - Private Collection

Tanagra (The Builders, New York)

Childe Hassam's images of New York City life were popular among the American upper class who appreciated how his Impressionist approach softened and beautified the urban grid. This work, while predominantly an interior scene, juxtaposes this refined domestic space with the modern city, visible through the open curtains.

At the painting's center, an elegant woman holds a small sculpture, identified in the title as a Tanagra. This style of ancient Greek terracotta had been widely popular during the 19th century, admired for their delicate realism. This classical reference is amplified by the woman's flowing gown that evokes both a classical Greek garment and a Japanese silk. The room is richly appointed with the inclusion of an elaborately decorated Japanese folding screen and blue-and-white porcelain bowl on a highly polished table. The elegant apartment radiates with Impressionistic light and color; even the lace-curtained window shimmers with blue highlights.

Hassam's painting suggests a certain ambivalence. While the interior is warm and rich, it appears static when compared to the city outside. The woman herself echoes the statue, particularly as her pale complexion contrasts with the vivid palette of her surroundings. The Japonism in this work conveys the splendor of a distant and exotic world, but also a sense of a world that belongs to the past.

Oil on canvas - Smithsonian Museum of American Art, Washington DC

Beginnings of Japonism

Precedents

Japonism built upon the Orientalist influences that were pervasive in European Neoclassical and Romantic art. The 18th-century aristocratic fashion for chinoiserie, based in imported Chinese art, merged with styles learned from French colonialist expansion in the Middle East and northern Africa. In the first half of the 19th century, artists as varied Eugène Delacroix and Jean-Auguste-Dominique Ingres turned to Orientalist subjects, developing dramatic intensely colored scenes as seen in Delacroix's Death of Sardanapalus (1827) or reconfiguring figurative work with sensual treatments such as Ingres's La Grande Odalisque (1814).

Japan, which (with the exception of its contact with the Dutch) had been isolated since 1633, was forced to accept international trade agreements after the 1852 arrival of Commodore Matthew Perry and the United States Navy. The 1854 Convention of Kanagawa compelled international exchange and, as a result, Japanese artworks and objets d'art were extensively imported into Europe. This provided an introduction to a new history of art production, including the format of Ukiyo-e prints. Collectors rushed to acquire and exhibit Japanese objects, while the affordable price of many prints encouraged artists to collect them.

Félix Henri Bracquemond in France

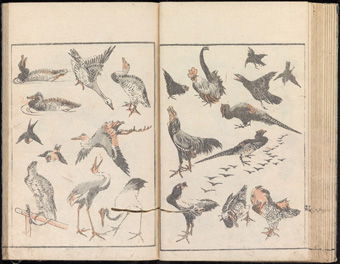

The French artist Félix Henri Bracquemond was primarily known in the early 1850s for his etchings, which included landscapes, portraits, and studies of birds. He was also celebrated for his mass-produced interpretations of paintings by artists such as Gustave Moreau and Jean-Baptiste-Camille Corot, creating affordable reproductions that launched a revival of engraving and etching in France.

In the early days of trade, cheap Japanese prints were often used as an inexpensive and attractive way to wrap porcelain for shipping. Finding some such prints in his dealer's shop, where they had been included as mere packing material, in 1856, Bracquemond discovered the Hokusai Manga (1814). While today manga is used as a term for comic books, this was an album of woodblock prints by Katsushika Hokusai that depicted landscapes, birds, flowers, and everyday scenes. Bracquemond was particularly drawn to Hokusai's sketches in the style of Kachô-ga, a Japanese genre, which captured individual specimens of flowers and birds in close detail.

When Bracquemond received an 1860 commission from Eugène Rousseau to create tableware, he based the designs on Japanese prints, including Hokusai's Manga, Taito's Flower and Bird Paintings (1848) and Hiroshige's Grand Series of Fishes (1830). His Service Rousseau (c. 1867) was among the first works to showcase the inspiration of Japanese art. The set was enormously popular, included in both the 1876 Paris Universal Exhibition and Philadelphia Centennial Exhibition (the same year) as an example of French porcelain. While it might seem incongruous to display work so heavily indebted to Japanese sources as an example of French art, contemporaries viewed the two traditions as totally compatible. The poet Stéphane Mallarmé specifically praised the Service Rousseau as an expression of French artistic sensibility. Thus, from the beginning, Japanese art and design was not considered to be the inclusion of foreign elements but reframed as an expression of European artistic impulses and development.

Bracquemond was equally well known for his printmaking, and most of his engravings were of animals or landscapes, like his Reed and Teals (1882). His work encouraged a number of artists, including Édouard Manet, Camille Pissarro, and Edgar Degas, to explore the artistic possibilities of printmaking. He became a founding member of the "Société du Jing-lar," a group brought together by their admiration of Japonism, which included Henri Fantin-Latour, Marc-Louis Solon, and Carolus Durgan. Bracquemond was also an influential author; his book, Du dessin and la couleur (Design and Color) (1886) was also important to the next generation of artists, including Vincent van Gogh.

Anglo-Japanese Style in Britain

Following an 1851 exhibit of Japanese art and objects in London, British artists and collectors began a fascination with what was dubbed the "Anglo-Japanese" style. Indeed, this show had such an immediate and forceful impact that the Museum of Ornamental Art (now known as the Victoria and Albert Museum) began acquiring Japanese objects in 1852, adding mostly porcelain and lacquer works to its permanent collection. In the following decade, exhibits of Japanese art occurred throughout Britain, Ireland, and Scotland, fueling this enthusiasm for the style in both the public and the artistic community.

The London International Exhibition of 1862 displayed a wide selection of Japanese art alongside works by British designers, like Christopher Dresser and Edward William Godwin, that incorporated Japanese design. This aesthetic, which predominantly featured ebonized rectangular forms with little decoration, came to be known as the Anglo-Japanese style. The Aesthetic Movement developed at this same time and the two styles heavily influenced each other. For example, James McNeill Whistler Tonalist composition, Harmony in Gold and Blue: The Peacock Room, also exemplifies the Aesthetic Movement and the Anglo-Japanese style. These directions in art would also lead to the Arts and Crafts and Art Nouveau movements.

Ukiyo-e

Ukiyo-e, or "pictures of the floating world," refers to a genre of Japanese woodblock prints. These inexpensive prints were produced in variety of styles, some using only black ink, while others used layers of color or added materials like metal flakes or glue to create textured, shimmering, or lacquer-like surfaces. Considered a low form of art created for merchants and workers, ukiyo-e originated in 1670, but soon became a form of art that was known both for its appeal to the average person and its artistic quality.

The work of the great masters of ukiyo-e, Kitagawa Utamaro, Utagawa Hiroshige, and Katsushika Hokusai greatly impacted European artists. Some artists, like Henri de Toulouse-Lautrec, were particularly drawn to Japanese prints depicting urban night life and its famous or notorious denizens. Utamaro, known primarily for his prints of beautiful Japanese women, influenced artists like Whistler. Others, like Edgar Degas, were more interested in composition strategies and the portrayal of figures in unconventional poses. Hiroshige's work, which focused on landscape and scenes of ordinary life (unlike the more common depictions of celebrities and scenes of what were called Tokyo's "pleasure district") influenced Impressionist and Post-Impressionist artists like Vincent van Gogh. Indeed, van Gogh made multiple copies of images from Hiroshige's One Hundred Famous Views of Edo (1856-58). Some works became widely popular: Hokusai's The Great Wave off Kanagawa (c. 1831), an iconic work became known worldwide and remains very popular.

La Porte Chinoise

To meet consumer demand, many small stores and teashops began selling Japanese objects in the early 1860s. La Porte Chinoise became a destination and an artistic hub. Having lived in Japan, in 1863 the French merchant E. de Soye opened the shop in Paris, and it actually specialized in imports from Japan, China, and other Asian countries. French artists like Édouard Manet, James Tissot, Theodore Duret, and Henri Fantin-Latour frequented the store, as did the British artists Dante Gabriel Rossetti and Whistler. Many of the fans, screens, textiles, and porcelains that Whistler included in his paintings like Variations in Flesh Colour and Green: The Balcony (1864-79) were purchased there. Interestingly, rivalries occasionally flared as artists competed to buy or reserve the best objects; Rossetti complained in 1864 that Tissot had purchased all the shop's kimonos.

Siegfried Bing and Art Nouveau

First introduced to Japanese prints through Bracquemond, in the 1870s, the German-French art dealer Siegfried Bing began importing Japanese objets d'art; and recognizing a demand for the style, he hired artists and designers to create similarly styled work.

Bing launched the journal Le Japon artistique: documents d'art et d'industrie in 1888. The magazine promoted Japanese art and objets d'art to an international audience, appeared monthly in English, French, and German, until its demise in 1891. Its influence was far-reaching, impacting the late work of Pre-Raphaelite artists, Post-Impressionists (like Vincent van Gogh, who was briefly hired to promote the magazine), and the next generation of artists such as the Vienna Secessionist Gustav Klimt.

Following the collapse of the magazine, in 1895, Bing founded the Maison d l'Art Nouveau, a gallery where he sold and promoted Japanese art alongside contemporary fine art and decorative objects by Édouard Vuillard, Edward Colonna, William Benson, George de Feure, Eugène Gaillard, Henry van de Velde, and Louis Comfort Tiffany.

Bing's influence was greatest upon the development of Art Nouveau, as his magazine, galleries, and attending exhibitions, brought together his enthusiasm for Japonism with stylistic trends that were emerging across Europe. The resulting combination came to be known as Art Nouveau, inspired (in part) by the name of Bing's gallery.

Japonism: Concepts, Styles, and Trends

Painting

Perhaps the most extensive and far-reaching impact of Japonism was reflected in painting. The foundations of modern art, particularly the emphasis on the flattened and decorative surface, were based on innovations found in Japanese woodblock prints. Arriving as artists sought new ways of depicting their world and a break from the Western Renaissance tradition, the Japanese aesthetic was a major impetus in the development of Impressionism, Post-Impressionism, Aestheticism, Art Nouveau, and Tonalism; it also influenced members of the Pre-Raphaelite and Nabis groups. Virtually all of the Impressionists were influenced by ukiyo-e prints, inspired by the everyday subject matter, limited palette and flat planes of color, asymmetrical composition, and unexpected points of view. Claude Monet's extensive collection of prints can be seen today at his house/museum in Giverny, France; Vincent van Gogh and Auguste Rodin also amassed large collections of prints.

Among the Post-Impressionists, van Gogh, Toulouse-Lautrec, Paul Gauguin, Georges Seurat, Camille Pissarro, and Paul Cézanne, were all influenced by the woodblock prints. Cézanne's series of paintings featuring Mont Saint-Victoire (c. 1886-88), show the mountain in the distance with trees framing it in the foreground, similar to Hokusai's Fuji Seen from the Katakura Tea Plantation in the Province of Suruga (c. 1830-31). Even Cézanne's repeated versions of this subject parallels Hokusai's repetition in Thirty-six Views of Mount Fuji. The depictions of casually posed figures common to Hokusai's images influenced the figurative work of Edgar Degas and Mary Cassatt, as well as Toulouse-Lautrec's portraits of the denizens of Paris nightlife. The flat pictorial space, use of rectilinear composition and exaggerated gestures in Seurat's Neo-Impressionist The Circus (1889) were all influenced by Japanese prints.

In England, Whistler blurred the boundaries between Tonalism, the Aesthetic and Anglo-Japanese styles, echoing prints by Hokusai in works such as Nocturne: Blue and Gold - Old Battersea Bridge (1872-75). Edward Burne-Jones and Dante Gabriel Rossetti,part of the late Pre-Raphaelite group incorporated elements into their work, such as the flatness and tiered vertical composition of Burne-Jones's The Nativity (1887). It also influenced the Japanese-inspired aesthetic of Beardsley's block print, Peacock Skirt (1894).

Architecture

Japanese design influenced an international assortment of architects. In England, Edward William Godwin was a leader in developing the Anglo-Japanese style. Among the first to adopt elements of Japanese design into his Aesthetic buildings and interiors, he built The White House (1877-78) as a private residence for Whistler. The simplified contours and rectilinear forms of Japanese prints were also important to Louis Bernard Bonnier's design for Bing's Maison d l'Art Nouveau (1895).

The Prairie School style of Frank Lloyd Wright was influenced by Japanese architecture, which he first encountered at the 1893 Columbian World Exposition in Chicago. Travelling to Japan in 1905, he collected hundreds of prints, which informed the rectangular forms and simplified elements of his designs. In his book, The Japanese Print (1912) he explained, "A Japanese artist grasps form always by reaching underneath for its geometry." He was also deeply influenced by the Japanese philosophy that a building should be open to and part of its environment. Marion Mahony Griffin, who worked with Wright for fifteen years. also incorporated Japanese elements into her later designs for the city of Canberra in Australia and, subsequently, in India.

Design

Japonism affected nearly all facets of late-19th century European design, from tableware to furniture to high fashion. Following the first, 1851 exhibit of Japanese work in London, English designers like Godwin and Christopher Dresser began incorporating Japanese design in their designs for furniture and household items. Dresser is credited for the first Anglo-Japanese piece of furniture: an ebonized chair displayed at the 1862 International Exhibition in England. Harmony in Yellow and Gold - The Cloud Cabinet (c. 1878), designed by Godwin and painted by Whistler is a notable example of the Anglo-Japanese and Aesthetic styles. James Hadley used Japanese pictorial elements in his designs for Royal Worcester Porcelain.

In Paris, textiles, furniture, tableware, and interior décor items infused with Japanese elements became ubiquitous. The fashion magazine, Journal des demoiselles promoted clothes in "the Japanese style" in 1867 and the writer Emile Zola commented that department stores in Paris were even selling Japanese-style umbrellas.

Later Developments - After Japonism

Japonism faded in the early 1900s with the arrival of avant-garde modernist abstractions, although the rise of Primitivism can be linked to its role in popularizing non-Western sources. Picasso's proto-Cubist Les Demoiselles d'Avignon (1907) or Matisse's Fauve Dance (1910), can be seen as following in the footsteps of earlier generations that had similarly turned to Japanese and Asian work. Many artists, following the example of Gauguin, turned to the artworks of what were then considered to be 'primitive' cultures, studying African masks and statues and incorporating their elements and principles into a modern idiom.

Some scholars have suggested that as the most often emulated Japanese printmaker, Hokusai could be considered an implicit "father" of modern Western art, since Tonalism, Impressionism, Post-Impressionism, Art Nouveau, and the Aesthetic movement were informed by the broad planes of color, asymmetrical compositions, rectilinear forms, unconventional poses, and everyday subjects of his prints.

Whistler's Nocturnes can be seen as the beginning of a development toward abstraction, and his Peacock Room informed the thinking of Robert Motherwell, David Smith, and later conceptual artists like Darren Waterson in the creation of an immersive space that seeks to envelope the viewer.

The Japanese-influenced architecture of Frank Lloyd Wright reconfigured architectural design, and the Anglo-Japanese style, practiced by Godwin and Dresser, prefigures the sparse geometric design of Bauhaus, De Stijl, and The International Style.

Japonism also had a noted influence upon the development of new museums and collections. It featured prominently in the expansion of the British Museum of Ornamental Art (now known as the Victoria and Albert Museum), which began adding Japanese work to its collection as early as 1852. Isabella Stewart Gardner, who was close friends with Whistler, pioneered collecting Asian art in America; her gifts to the Boston Museum of Fine Arts have created what some scholars believe to be the best collection of Japanese art outside of Japan. The Freer Gallery of Art in Washington D.C., which houses the Peacock Room of Whistler, is home to the largest research library on Asian art in the United States.

Useful Resources on Japonism

-

![Looking East: How Japanese Art Inspired Monet, van Gogh, and other Western Artists]() 27k viewsLooking East: How Japanese Art Inspired Monet, van Gogh, and other Western ArtistsOur PickBy Asian Art Museum

27k viewsLooking East: How Japanese Art Inspired Monet, van Gogh, and other Western ArtistsOur PickBy Asian Art Museum -

![The Peacock Room Comes to America]() 24k viewsThe Peacock Room Comes to AmericaExplanation by curators and a view behind the scenes

24k viewsThe Peacock Room Comes to AmericaExplanation by curators and a view behind the scenes

-

![Trading in Japonisme: the French Obsession with Japanese Art]() 6k viewsTrading in Japonisme: the French Obsession with Japanese ArtOur PickBy Julie Nelson Davis, James Ulak, Gabe Weisberg, / Freer/Sackler

6k viewsTrading in Japonisme: the French Obsession with Japanese ArtOur PickBy Julie Nelson Davis, James Ulak, Gabe Weisberg, / Freer/Sackler -

![The Many Worlds of Ukiyo-e]() 125k viewsThe Many Worlds of Ukiyo-eOur PickBy Sarah E. Thompson / Museum of Fine Arts, Boston, Massachusetts

125k viewsThe Many Worlds of Ukiyo-eOur PickBy Sarah E. Thompson / Museum of Fine Arts, Boston, Massachusetts -

![Vincent van Gogh and Japan]() 22k viewsVincent van Gogh and JapanOur PickBy Simon Kelly / FristCenter lecture

22k viewsVincent van Gogh and JapanOur PickBy Simon Kelly / FristCenter lecture