Summary of Post-Painterly Abstraction

Post-painterly abstraction is a broad term that encompasses a variety of styles that evolved in reaction to the painterly, gestural approaches of some Abstract Expressionists. Coined by Clement Greenberg in 1964, it originally served as the title of an exhibition that included a large number of artists who were associated with various tendencies, including color field painting, hard-edge abstraction, and the Washington Color School.

Key Ideas & Accomplishments

- Greenberg believed that, during the early 1950s, Abstract Expressionism (or, as he preferred to call it, "Painterly Abstraction") had degenerated into a weak school, and, in the hands of less talented painters, its innovations had become nothing but empty devices. But he also believed that many artists were advancing in some of Abstract Expressionism's more fruitful directions - principally those allied to color field painting - and these were yielding to a range of new tendencies that he described as "post-painterly."

- Greenberg characterized post-painterly abstraction as linear in design, bright in color, lacking in detail and incident, and open in composition (inclined to lead the eye beyond the limits of the canvas). Most importantly, however, it was anonymous in execution: this reflected the artists' desire to leave behind the grandiose drama and spirituality of Abstract Expressionism.

- Some critics, including Clement Greenberg and , remarked on the decorative character of some post-painterly abstraction. In the past, Harold Rosenberg had described failed Abstract Expressionist paintings as "apocalyptic wallpaper," suggesting that decorative qualities were to be avoided. The new tendency suggested a change in attitudes.

Artworks and Artists of Post-Painterly Abstraction

Blue Balls VII

The work of Sam Francis contains many visual indicators reminiscent of the "action painting" or art informel schools of Abstract Expressionism. What made Francis a unique painter was his technique of tachisme, in which heavy blotches of free-flowing oil paints were allowed to drip down and, in the process, create an accidental design. In Blue Balls VII, which was included in the 1964 Post-Painterly Abstraction exhibit, Francis used far less paint than he was accustomed to. The end result showcases razor-thin lines of blue paint that cascade down from the more prominent blotches applied throughout the canvas.

Oil on canvas - Museum of Contemporary Art, Los Angeles

Dance

California native John Ferren (who was actually older than most of the first-generation AbEx artists) retained elements of what Greenberg called the "Tenth-Street touch." He described this as when "The stroke left by a loaded brush or knife frays out, when the stroke is long enough, into streaks, ripples, and specks of paint. These create variations of light and dark by means of which juxtaposed strokes can be graded into one another without abrupt contrasts." Greenberg criticized the "touch" as a safety net of sorts for those artists having trouble creating a unified image on an abstract plane. However, he praised Ferren's Dance and other similar works for applying the "Tenth-Street touch" and at the same time "boxing it within a large framing area" and managing "to get a new expressiveness from it."

Oil on canvas - Katharina Rich Perlow Gallery, New York

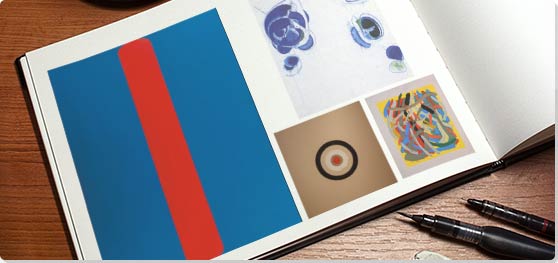

Red Blue

Kelly's Red Blue recalls in many ways Barnett Newman's signature "zip" paintings, with the single dividing line cutting through an otherwise unified field of color. What set Kelly's painting apart was the way in which he applied the pigment. Kelly allowed his diluted oil paints to soak into the canvas, rendering the surface a clean and utterly flat picture plane. His red divider is also much wider than Newman's "zips," and applied to create a cleaner, simpler hard-edged line. Another key characteristic of Kelly's hard-edge, Color Field paintings was his tendency to only use two opposing colors.

Oil on canvas - Oklahoma City Museum of Art

The Key

In Greenberg's essay for the Post-Painterly Abstraction catalog, he was careful to point out that the post-painterly artists were in fact rejecting the technique of action painting, but this rejection in no way constituted an attempt to return to neo-plasticism or synthetic Cubism. This assertion is difficult to believe upon looking at Mehring's The Key (which was part of the Post-Painterly exhibit), which visibly recalls Mondrian's geometric abstractions, at least in form if not in color. However, what set Mehring's painting apart was his use of perfect symmetry, both in depicted and literal shape (painterly form and canvas measurement, respectively), for which Mondrian was not known. In fact, all three of Mehring's paintings at the 1964 show measured 78"x78".

Magna on canvas - Gary Snyder Project Space, New York

Cycle

One of Noland's signature series of paintings was the Target paintings, which for him also doubled as his own brand of Color Field Painting and geometric abstraction. In Cycle Noland created something particularly uncomplicated and, in fact, the near opposite of the Color Field style. Cycle's central target is entirely surrounded by bare canvas; a compositional decision also made by fellow painter Morris Louis. What Noland achieved with this painting was most likely what Greenberg had in mind when he wrote about the post-painterly rejection of the "doctrine" of Abstract Expressionism. By creating a strikingly simple geometric form and emphasizing more canvas than paint, Noland was definitely moving beyond the visual confines of freeform abstract painting.

Acrylic on canvas - The Phillips Collection, Washington DC

Isis Ardor

Greenberg wrote in the Post-Painterly catalog that many of the artists represented "have a tendency...to stress contrasts of pure hue rather than contrasts of light and dark...In their reaction against the 'handwriting' and the 'gestures' of Painterly Abstraction, these artists also favor a relatively anonymous execution." Olitski's Isis Ardor was one of the paintings included in the 1964 show and was certainly an ideal example of a painting that opposed flat planes of color. The contrasts Greenberg spoke of appear to be more of a visual tension in Olitski's painting. His three colors, interacting with small portions of bare canvas, sit so tenuously in the canvas that it almost appears as if they are struggling to resist one another, and with few exceptions they succeed.

Acrylic on canvas - Virginia Museum of Fine Arts, Richmond, VA

Beginnings of Post-Painterly Abstraction

In 1964, critic Clement Greenberg was recruited by the Los Angeles County Museum of Art (LACMA) to curate an exhibition devoted to young abstractionists. He was a natural choice to curate such a show, as by the late 1950s he had a prominent reputation as a defender of contemporary abstract art. Greenberg called the exhibition Post-Painterly Abstraction, although in the essay he wrote for the exhibition catalog he never actually referred to the style by name. Instead, he defined it by what it was not - "painterly abstraction," or the style of the Abstract Expressionists.

Greenberg selected several East coast-based artists whose work he was already familiar with, such as Morris Louis and Helen Frankenthaler. As for the Bay Area artists, such as John Ferren and Sam Francis, debate continues as to who exactly selected them for the exhibition. While some credit James Elliott, a curator at the L.A. County Museum, the original exhibition catalog indicated that Greenberg was taken to see several works in California by Fred Martin of the San Francisco Art Association.

There was a total of 31 artists selected for Post-Painterly Abstraction, and each of them was represented by three paintings apiece, most of which were made between 1960 and 1964. All of the artists were either natives of the USA or Canada.

Post-Painterly Abstraction: Concepts, Styles, and Trends

Greenberg borrowed from the Swiss art historian Heinrich Wölfflin in devising the term post-painterly abstraction. Wolfflin had popularized the term "painterly" to describe characteristics of the Baroque, which separated it from classical, or Renaissance art. Greenberg believed that abstract painting had evolved amidst a trend towards "painterly" painting, but had swung back towards cleaner composition and sharper forms in the 1920s and 1930s, under the influence of Mondrian, Synthetic Cubism, and the Bauhaus. Abstract Expressionism marked another swing towards the painterly, and the inevitable reaction against it was away from it once again - though Greenberg emphasized that post-painterly abstraction was not a return to the past.

Although many artists associated with the tendency worked with clean lines and clearly defined forms (such as Frank Stella, Ellsworth Kelly, and Al Held), others explored softer forms. Helen Frankenthaler, for example, became well known for soaking paint into untreated canvas, which created a visual effect of color opening up the canvas. Rather than working up the paint into a rich texture on the surface of the canvas, as many artists of the previous generation had done, she allowed paint to seep into the canvas itself, creating a vibrant and utterly flat visual plane. Other post-painterly artists, such as Morris Louis, Kenneth Noland, and Jules Olitski, picked up on Frankenthaler's soaking technique to create a variety of color field paintings of their own unique design.

Later Developments - After Post-Painterly Abstraction

In June 1965, an exhibition took place at the Washington Gallery of Modern Art in Washington, D.C., called Washington Color Painters. Included in the show were many of the artists who had participated in Post-Painterly Abstraction in Los Angeles the previous year. They included Morris Louis, Kenneth Noland, Howard Mehring, Gene Davis, and Thomas Downing. This exhibit marked the official beginning of what became known as the Washington Color School, which was in many respects a sub-movement of color field painting. The Washington painters created minimalist canvases composed of stripes, thin bands of alternating colors, and geometric shapes.

In November of 1966, in the pages of Artforum, critic Michael Fried published the essay, "Shape as Form: Frank Stella's New Paintings." In it he referred to the recent works of Morris Louis, Kenneth Noland, and Jules Olitski - all in addition to Stella's work - as a "new illusionism." The importance of this, according to Fried, was the difference between literal and depicted shape. The old standard of abstract painting, or the "old illusionism," was for the artist to take a basic square or rectangular canvas support and use that template to depict whatever they pleased. What artists like Stella and Noland had achieved, according to Fried, was the complete transformation of paintings' literal form. By using oddly-shaped, oblong, and asymmetrical canvases, they had made the form of the painting and the shape of the canvas synonymous things. Therefore this "new illusionism" marked the advent of the shaped canvas, as a singularly modern invention.

Useful Resources on Post-Painterly Abstraction

- Modernism's Masculine Subjects: Matisse, the New York School, and Post-Painterly AbstractionOur PickBy Marcia Brennan

- Colourfield Painting: Minimal, Cool, Hard Edge, Serial and Post-Painterly Abstract Art of the Sixties to the PresentBy Stuart Morris

- Color as Field: American Painting, 1950-1975By Karen Wilkin, Carl Belz

- The Shape of Color: Excursions in Color Field Art, 1950-2005By Christian Eckart, Mark Cheetham, Sarah Rich, Raphael Rubinstein, Robert Hobbs, David Moos, Polly Apfelbaum, Mary Heilmann, Peter Halley, Matthew Teitelbaum