Summary of Synchromism

At the time when French, German, and Eastern European artists were deftly pushing painting toward complete abstraction in the second decade of the 20th century, two audacious Americans, Morgan Russell and Stanton Macdonald-Wright, then living in Paris, made their own forays into abstraction, calling their new movement Synchromism. Russell coined the term when he thought of the word "symphony," and "chrome" flashed across his mind, so he put the two words together. The resulting paintings, called Synchromies, used the color scale in the way notes might be arranged in a musical piece, as the two artists wrote, "Synchromism simply means 'with color' as symphony means 'with sound'...."

Dismissing their artistic confrères, the Synchromists insisted that they had finally used color abstractly and not descriptively. While their bombast offended their European colleagues, the Synchromists had a small, if short-lived, following back in the United States and are known for being America's first avant-garde group.

Key Ideas & Accomplishments

- Above all, the Synchromists insisted not on the optical effects of color but the materiality and tactility of color; that is, they wanted to use color, and not the more traditional line, to create form and space. By layering and juxtaposing different colored planes, Synchromist paintings create space through a back and forth movement, or a push-pull, of chromatic forms.

- Synchromists often thought of painting in musical terms. Arranging colors in a composition was likened to arranging sounds in a musical score. Like many contemporary abstract artists, the Synchromists envisioned pictorial abstraction operating in the same non-representational manner as music. Like musical notes and compositions, color and form could engender emotions and sensations without direct representation.

- Despite their insistence on complete abstraction, the sculptural figure, especially as seen in the Renaissance artist Michelangelo, was foundational for the Synchromists' conception of form and space. Michelangelo's twisting figures conveyed a generative force that the Synchromists wanted to achieve in two dimensions.

Artworks and Artists of Synchromism

Synchromy in Orange: To Form

This large canvas, about eleven feet square, with a frame painted by the artist that both contains the painting and lets the painting spill into the space around it, has been described as Russell's greatest work. The planes of saturated colors that curve and fold have a remarkable density and three-dimensional effect. The green and red triangles on the upper left seem to buckle with intensity, weighing on the yellow, green, and white irregular geometric shapes in the center. A dynamic stacking of various planes creates a sense of unfurling while being simultaneously energetically contained.

Russell used his sculptural study of Michelangelo's the Dying Slave as the foundation for this work, as he evolved his abstract composition. As he said, "I always felt the need to impose on color the same violent twists and spirals that Rubens and Michelangelo imposed on the human body." When shown at the Salon des Indépendants, the work was titled Synchromie en orange: la création de l'homme conçue comme le résultat d'une force génératrice naturelle (Synchromy in Orange: the creation of man conceived as a result of a natural generative force). The artist meant the work to be a tour de force of the Syncrhomist style as well as a response to the large abstract Orphist paintings of the Delaunays and Franz Kupka.

Oil on canvas - Albright-Knox Art Gallery, Buffalo, New York

Day of Good Fortune

This painting, depicting two dancing, nude women, shows Davies bringing a Synchromist treatment to his characteristic figurative work. The woman on the left, rendered primarily in tones of white, her arms over her head, bends forward gracefully, while on the right, another woman, a kaleidoscope of color, lifts her left leg and arches her arms above her head. Depicted in variously colored geometric shapes, the women become closer to abstracted figures of movement, flowing into the shapes that extend and swirl around them like the music that attends them. The black background, suggesting the backdrop of a stage, creates a sense of space through which the music swirls, embodied in the movements of the dancers and extending out of the pictorial frame.

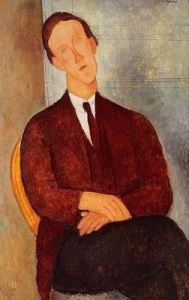

Davies, already well-known for his somewhat lyrical and Symbolist figurative work that had a fundamentally decorative effect, was equally interested in more avant-garde art. He helped to organize the 1913 Armory Show that introduced European avant-garde work to the American art world, and his subsequent explorations of other styles, including Cubism, show the impact the show had on his own work. Both Russell and Macdonald-Wright attempted Synchromist figurative work, as seen in Macdonald-Wright's self-portrait, though not as successively as Davies does here.

Oil on canvas - Whitney Museum of Art, New York, New York

Bubbles

The title of this work, assigned by its first owner the writer H. L. Mencken, suggests that the painting is illustrative, but in fact it was meant to be entirely abstract. Using a vibrant color scheme, the painting depicts a number of variously colored circular shapes radiating from its center, as larger varied geometric forms, predominantly blue, green, purple and yellow curve around it. Crescents of more intense color on the circles draw the viewer's eye up along the center right as if following a kind of implicit J shape.

Benton's painting, influenced by MacDonald-Wright's circular forms in Conception Synchromy (1914), exudes a sense of vibrant rhythm. A visual syncopated din and bustle is created by the juxtaposition of curvilinear shapes and angular geometric forms. The viewer's eye moves through the canvas, following the complex movement of color as one might hear the interplay of different instruments in a musical piece. Benton had a lifelong interest in music, and part of the effect of this work is based upon his understanding of how sound works. Created in waves, different notes bounce off one another, and the aural quality is changed.

Close friends with Macdonald-Wright, Benton tried Synchromism for a time and exhibited this painting at the Forum Exhibition in 1916, but, more importantly, he shared with Russell a profound interest in sculpture, saying, "Following the Synchromist practice at the time, I based the composition of these pictures on Michelangelo's sculpture." The implicit J shape, creating a sense of both physical movement and pictorial unity, and the emphasis upon the color triad of red, yellow, and blue, were derived from studying the Renaissance master's work. While Benton abandoned Synchromism, feeling dissatisfied with the results, the rhythm and vibrant color used in this work became noted elements in the American regionalist work for which he became famous.

Oil on canvas - Baltimore Museum of Art, Baltimore, Maryland

Improvisation

Interlocking shapes in primarily green, blue, and yellow tones suggest an extemporaneous feeling. The intersection of the yellow vertical and horizontal shapes in the center gesture energetically outwards toward greyish violet and green curved blades in the bottom third of the painting and toward lighter blue curves above. Dasburg's title, Improvisation, recalls the titles of Kandinsky's early abstract paintings that he likened to music. Dasburg later explained his "improvisations" to an interviewer, "You invented what you were doing. In other words, an invention of your own and not a replica, something you had seen, any recognizable things, but independent of an object...."

Andrew Dasburg was a close friend of Morgan Russell, and this painting may have been one of the nine paintings he showed in The Forum Exhibition of Modern American Painters in 1916. Most of Dasburg's work during this period has been lost or destroyed, and he later became best known for his landscapes of New Mexico, where he subsequently resided. His interest in landscape can already be seen in this work's color palette, as the darker greens that dominate the foreground contrasted with the brighter blues at the top create a horizon effect. His use of geometric shapes, many of them curved or resembling the blades or stalks of vegetation, suggest an organic energy out of which the center yellow seems to spring, almost like a figure raising its arms.

Oil on canvas - Private Collection

Breakfast Table

Davis depicts a table as seen from above. A circle dominates the lower two thirds of the painting, and a pitcher, not depicted on the table, floats above it, occupying the top of the canvas. Here, Davis explores Synchromism's dynamic irregular geometric shapes, jostling with vibrant color, combined with the grid of Cubist shallow space.

Following the 1913 Armory Show, Davis experimented with a number of avant-garde movements, including Cubism, Orphism, Futurism, Synchronism. Though the influence of Cubism is also apparent in the breaking up of forms, the emphasis on bold and vibrant colors that pulsate suggest the bright liveliness and cacophony of morning. Davis had a deep interest in popular culture and in jazz music and later became well known for his unique Cubist style that juxtaposed angular planes to mimic the rhythm and dissonance of jazz.

Oil on canvas - Crystal Bridges Museum of American Art, Bentonville, Arkansas

Synchromy in Blue

This work uses geometric planes of varying shades of green and blue, layered with curvilinear planes of pink and red, occasionally punctuated by areas of yellow and white. Two primarily white triangles intersect the painting from left and right in the upper third, meeting a center triangle, its apex extending beyond the canvas' surface. Macdonald-Wright creates a sense of depth in the work by layering the planes of color, and as a result, the painting has a feeling of solidity and gravity. Color becomes more tactile and physical in Macdonald-Wright's composition.

While the painting is non-representational in overall effect, one can make out the shape of a seated male figure, with his knee bulging to the left, and his back and shoulder on the right. This is yet another reference to the sculptural qualities of the much older art of Michelangelo.

Oil on canvas - The Museum of Modern Art, New York, New York

Color Form Sychromy (Eidos)

This painting focuses on an abstract form made up of irregular shapes of color that create a spinning motion in the center of the canvas. The spiraling form in the center is surrounded by areas of black that create a sense of space, and the effect is as if the form were opening up into the top part of the canvas. The lower left corner of the canvas consists of small, interlocking shapes of color, primarily somber-hued red and green.This work shows Russell both following and expanding upon his own painterly dicta, as he said, "Forget the linear outline of objects (...) never will you arrive at expression in painting until the habit is lost - ignore borders - profiles except when light renders them prominent - make little spectrums that is all - an order of little spectrums."

Russell returned to his Synchromist style in 1922 after recovering from a period of difficulty and depression. In the Eidos paintings, any sense of a figurative basis disappears, and the works emphasize a spinning space, rather than the spiraling motion of his earlier Synchromist work. The artist hoped to display the works with the use of a kinetic light machine to suggest the lingering effects of fireworks in the room.

Oil on canvas - The Museum of Modern Art, New York, New York

Beginnings of Synchromism

A number of influences came together in the development of Synchromism, including the influence of the Fauves, and particularly Henri Matisse, as well as the work of Paul Cézanne and the Cubism of Pablo Picasso. Additionally, the color theories of the Canadian artist Ernest Percyval-Tudor as well as atonal music and sculpture, particularly on the part of Russell, contributed to the formulation of the movement.

Ernest Percyval-Tudor

Both Russel and Macdonald-Wright made their ways to Paris in the first decade of the 20th century to pursue their artistic training. In 1911, the two young artists met as students while studying with Ernest Percyval-Tudor, a Canadian artist based in Paris. Percyval-Tudor's color system emphasized "espacement," which he defined as the juxtaposition of colors taken from a particular color scale, with intervening neutral colors, to create a visual effect like melody in music. Other artists who also worked with Tudor were Lee Simonson, who went on to become a modernist theatre set designer, John Edward Thompson who later became known as "the dean of Colorado art," for introducing modern art to that part of the West, George Carlock, and, most notably, Thomas Hart Benton, with whom Macdonald-Wright had a close artistic friendship and who, subsequently, incorporated many Synchromist tendencies in his work.

Percyval-Tudor's color theory was based upon the idea that the twelve colors of the spectrum corresponded to the twelve steps of the musical scale. While drawing from the nineteenth-century color theory of Michel Eugène Chevreul and Ogden Rood, Percyval-Tudor was not interested in optical effects but rather the psychological and emotional effects of color and their combinations. This emphasis upon the psychological effects of color distinguished Synchromism from earlier movements, such as Neo-Impressionism, which also used Chevreul's and Rood's theories and emphasized optical effects. For instance, as Macdonald-Wright was to write later, "Yellow-Orange has also a braggart tendency but at bottom it is weak and sickly. It is like the last pretenses dying in a pompous soul. On this account it has a quasi-sad note, like an old man who feels senility to be not far off." As a result, the two Synchromists felt that color could create an experience of pictorial and psychological reality and reveal the truth of the natural world, human nature, and human feeling.

Russell and Macdonald-Wright built upon Percyval-Tudor's ideas. In his notebook, Russell described "the search for a solution of the problem of color and light or 'a rationale of color." This emphasis upon a rational equivalence led Russell and Macdonald-Wright to further develop the analogy between color and music, where luminosity of color was equivalent to musical pitch, saturation was equal to the intensity of a sound, and the hue was equivalent to musical tone.

The Importance of Sculpture

Early in his artistic career Russell was most interested in sculpture, and he studied both painting and sculpture with Matisse. He was particularly drawn to the works of Michelangelo, Rodin, and Puget. Michelangelo's Dying Slave (1513-1515) was the direct inspiration for Synchromy in Green (1913). Michelangelo's sculpture, with its dynamic contrapposto pose, became a kind of obsession for the artist, as he strove to utilize color to create sculptural and dynamic forms in painting. Many of the Macdonald-Wright's and Russell's Synchromist works were based upon the nude figure.

Synchromy in Green was subsequently lost but a photograph of the work showed that it depicted Russell's studio with a sculpture in the foreground that Russell had made of the Dying Slave. In preliminary sketches, Russell evolved geometric forms that began to twist and buckle as he explored how to use color on the two dimensional surface of the picture plane to create sculptural volume. As he wrote in one of his notebooks, he wished "to make the form and space with waves of color - as Michelangelo does with waves of form."

Cubism

Russell not only studied with Matisse but also was familiar with Picasso's work, and in 1911, he made several studies of Picasso's Three Women (1908). Friends with the writer Gertrude Stein and her brother Leo Stein, both early promoters and art collectors, Russell encountered Picasso's ground breaking works at the Stein home. While the Synchromists aggressively critiqued the Cubists, and Picasso in particular, their works also strikingly broke up forms into geometric planes, as shown in Russell's Synchromy No. 3 (1917). The work shows Cubism's influence in its subject, a café table, a chair, and plate with fruit and a decanter, broken into Cubist angled planes, though rendered in the rich saturated color palette of Synchromism.

The First Public Exhibition of Synchromism

Russell exhibited his Synchromy in Green (1913) at the Salon des Indépendants in Paris in 1913, the first public launch of Synchromism. Though he and Macdonald-Wright were close artistic colleagues sharing their ideas of painting and color theory, Macdonald-Wright's Dawn and Noon (1913) also exhibited in the Salon was not Synchromist, though his following works did adopt the style. The poet and art critic Guillaume Apollinaire, described Russell's painting as a "vaguely Orphic painting," associating the work with Orphism, the color based movement, developed by Robert Delaunay and Sonia Delaunay-Terk in the preceding year. The brash young Americans disliked the comparison and later insisted there was no connection whatsoever.

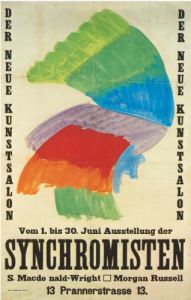

Der Neue Kunstsalon in Munich

In June 1913, Macdonald-Wright and Russell held their first Synchromist exhibition in Munich at Der Neue Kunstsalon. The pair exhibited twenty-eight paintings and included a co-written statement that promoted Synchromism as "the only possible version of reality capable of expressing the totality of different qualities applicable exclusively to painting." They faulted the "mediocre work" of most Impressionists and felt Cézanne was a "disastrous" influence. The statement made no mention of Robert and Sonia Delaunay who had launched Orphism, a similarly color based abstract movement, the previous year, or that the term "Synchromism" had first been used by Sonia Delaunay on an Orphist poster in the months before.

Synchromist Manifesto

At their subsequent 1913 show at the Bernheim-Jeune Gallery in Paris, Macdonald-Wright and Russell distributed their manifesto, and influenced by the bombast of the Italian Futurist manifesto declared that Synchromism had "finally solved the great problem of form and color." The two artists dismissed the Cubists and Futurists as "superficial" and "of secondary interest," and went to great lengths to distinguish Synchromism from Orphism, stating, "a superficial resemblance between" Orphism and Synchromist "has led certain critics to confuse them; this was to take a tiger for a zebra, on the pretext that both have a striped skin." In fact, Robert and Sonia Delaunay had also used the word Synchromism in relation to their own works in which contrasting colors created abstract compositions and were spoken of in terms of musical analogy.

Writing one of the few American avant-garde manifestos, Macdonald-Wright and Russell posited themselves as leaders both of modernist and of American art. However, their pugnacious dismissal of other artists and movements and their self-promotion alienated many, as the art historian and curator Will South said, "they turned off the very small art world there was in Paris." As a result, it was primarily American artists, like Thomas Hart Benton, Andrew Dasburg, Jan Matulka, Stuart Davis, and Patrick Henry Bruce who were drawn to the movement.

Treatise on Color (1924)

While there were several Synchromist exhibitions during World War I, by the end of the war, Synchromism as a movement began fading away as artists turned to other styles. Macdonald-Wright, though, continued to elaborate his Synchromist ideas. In 1924, having moved back home to California for lack of money, Macdonald-Wright published Treatise on Color, though, ironically, the comprehensive explanation of Synchromism appeared after the decline of the movement. Russell, who remained in Paris, also contributed to the treatise, as he and Macdonald-Wright continued to correspond with one another. Drawing on musical analogies, the Synchromist method began with choosing a color as a kind of base note. Once the artist had chosen the color, he would build upon the third and fifth colors on the spectrum, creating the equivalent of a musical chord. At the same time the theory developed color in terms of psychological and emotional effect, associating warm colors with expansive feeling and outward movement and cool colors with repose or receding movement. As art historian Henry Adams points out, however, this almost mechanical-like method proved very difficult, since "in music the sequence of notes is strictly linear and controlled, whereas in painting the placement of color does not follow an orderly pathway. Our eye can scan a painting in any direction, and as a consequence it's not possible for a painter to specify the exact sequence of color notes that the viewer will be tracing." This difficulty might be another reason Synchromism did not have a larger following.

In 1924, both artists further developed the founding ideas of Synchromism with Russell's concept of Eidos and Macdonald-Wright's interest in film and theatre, and his development of a kinetic light machine. Macdonald-Wright was also to have a burst of painting new Synchromies, though the works had noted representational elements, a trend that can be first seen in his Aeroplane Synchromy in Yellow-Orange (1920) which includes the engine, wing, and gears of an airplane above a few buildings in a Synchromist orange and blue sky.

Synchromism: Concepts, Styles, and Trends

Eidos

Just after a few short years, at the end of World War I, Synchromism as a movement came to an end, and Russell and Macdonald-Wright, like many other American artists, turned to representational art. Disillusionment with Europe and with avant-garde art made Social Realism more appealing to artists like Thomas Hart Benton, who was good friends with Macdonald-Wright and deeply influenced by Synchromism but who began developing American Scene painting.

However, in the early 1920's as he recovered from a period of difficulty and depression, Russell began painting Synchromies that he called "Eidos," taken from the Greek word for "form," that used a darker palette. The resulting paintings have a simplified central form that seems to spin in the surrounding black space. Russell intended the works to be presented by a kinetic light machine, an idea that he had first conceived in 1912 and for which he had created several preliminary sketches. He envisioned the art as a being presented as a visual symphony, accompanied by slow music.

Synchromist Theatre and the Synchrome Kaleidoscope

As Russell developed his Eidos and his ideas for a light machine, Macdonald-Wright, then living in California, was equally preoccupied with developing a kinetic light machine and nurtured an accompanying interest in film and theatre. In 1927, he began working with a theatrical group in Santa Monica and called his work "Synchromist Theater." The Christian Science Monitor described how "the action of the play takes place in nowhere, at no time, therefore to have other than a purely abstract setting would not only be incongruous but ridiculous. The mood induced by the use of these Synchromist settings is definite, and together with the use of Wright's color organ, which can throw any or all of the colors of the spectrum...evoke an illusion and atmosphere of a fresh sort." Though he continued to work on the idea and successfully built what he called a Synchrome Kaleidoscope in 1959, his efforts had only a local influence.

Later Developments - After Synchromism

Synchromism and its works largely disappeared from view after World War I, though Macdonald-Wright was very influential in bringing modernism to California art circles. Nationally, the movement's influence was most noted upon the artists, James Henry Daugherty who turned to Synchromism in works like his Synchromist Landscape (1933), and in the color abstractions of Patrick Henry Bruce. Other artists influenced by the movement included Jan Matulka, Morton L. Schamberg, and Jay Van Everen, Arnold Friedman, Alfred Maurer, Albert Henry Krehbiel, and Henry Fitch Taylor.

In 1976 the Whitney Museum of American Art's exhibition "Synchromism and American Color Abstraction: 1910-1925," which travelled to six major museums, revived interest and a critical re-evaluation of the movement. As a result, the movement was recognized as having played a more significant role in influencing American abstract art in the 1940s-1950s than previously thought. With its emphasis on the "idea of color defining form," as the curator Marilyn Kushner said, Synchromist ideas can be seen in Joseph Stella's Color Field spectrums and in the works of Marsden Hartley, Arthur Dove, Alfred Maurer, and Georgia O'Keeffe.

Macdonald-Wright's Treatise on Color (1924) is thought to have influenced the artist Frederick John de St. Vrain Schwankovsky's color theory that assigned a musical tone and emotional feeling to each color. An art teacher in Los Angeles, Schwakovsky's color theory had a profound impact on his most famous student, Jackson Pollock. Pollock later went on to study with Thomas Hart Benton, and Pollock's early work was also strongly influenced by Synchromist ideas and method.

Useful Resources on Synchromism

- Color, Myth, and Music: Stanton Macdonald-Wright and SynchronismBy Will South

- Synchromism and American Color Abstraction, 1910-1925Our PickBy Gail Levin

- Color & Form, 1909-1914: The Origin and Evolution of Abstract Painting in Futurism, Orphism, Rayonnism, Synchromism and the BlueBy Henry G. Gardiner

- Morgan RussellOur PickBy Marilyn S. Kushner