Summary of Abstract Expressionism: Second Generation

What then, in the wake of a revolution? After the rise and total dominance of Abstract Expressionism in the New York art scene, the question facing American painters in the early 1950s was whether the possibilities of painting had been exhausted, the medium's progression pushed to its logical end, following the dictum of the influential art critic Clement Greenberg. A group of artists with disparate styles and approaches who can be loosely categorized as second-generation Abstract Expressionists pointed the way forward. Hailing from New York but also Washington, DC and the San Francisco Bay Area, they had well understood the innovation of Abstract Expressionism, such as the all-over composition, the emphasis on the flatness of the canvas, and the bold use of color drips and splashes. Building on these, their works opened up to the outside world, rather than focusing on the expression of inner angst and drama like their predecessors: airy color and atmospheric sensations became a recurring mood, breaking from the density of the typical Abstract Expressionist canvas. Less beholden to a single art critical narrative, second-generation Abstract Expressionists were inventive and kept modern painting alive, a tradition which continues to the present day in the works of many contemporary artists influenced by them.

Key Ideas & Accomplishments

- The artists in this informal grouping experimented and came up with new painting techniques. These included the "staining" of raw, unprimed canvas with diluted paint, the physical manipulation of the canvas as a way to direct paint, even the use of a canvas so large one had to jump with a long-handled brush to reach its corners. These techniques resulted in forms of abstraction that had never been seen before.

- Although women artists had all along been present, the most prominent Abstract Expressionists had all been white men. Having been overlooked earlier, many women artists found a footing. Some, such as Helen Frankenthaler, even became an influence on their peers and younger male painters.

- The emergence of new approaches to painting in other geographic locations beyond New York, too, helped broaden the scope of the art world. In Washington, DC, African American painters such as Alma Thomas and Sam Gilliam made innovative and lasting contributions, while the congenial artistic environment of San Francisco spawned a new school of figurative painting.

Overview of Abstract Expressionism: Second Generation

Infusing the pictorial language of Abstract Expressionism with her distinctive approach to landscape painting, Joan Mitchell created meanings out of abstract forms that resonated deeply with her perception of the world - yet were not a mirror of it. "I paint from remembered landscapes that I carry with me - and remembered feelings of them, which of course become transformed," she explained, "I could certainly never mirror nature. I would like more to paint what it leaves me with."

Artworks and Artists of Abstract Expressionism: Second Generation

Mountains and Sea

Light, airy washes of paint breeze effortlessly through this painting, capturing the invigorating, expansive freshness of an oceanic landscape. Sketchy lines hint at the outlines of mountainous forms, but they are wispy and fragile, emphasizing the fleeting effects of nature. Rather than depicting a realistic place, the work conveys an emotional, individualized response to the memory of time and place before it slips away.

Frankenthaler made this painting when she was just 23 years old following a visit to the coastal regions of Nova Scotia, where the wide-open space and sharp, crisp air deeply moved her. But she went beyond representation in this painting, evoking instead an experiential moment through abstraction. The art critic Barbara Rose admired Frankenthaler's ability to create "the freedom, spontaneity, openness and complexity of an image, not exclusively of the studio or mind, but explicitly and intimately tied to nature and human emotions."

This painting was a breakthrough for Frankenthaler, in which she first pioneered the "soak-stain" technique by pouring turpentine-diluted paint directly onto raw, unprimed canvas laid out flat on the floor. This process took influence from Jackson Pollock and his "all-over" floor paintings, but whereas Pollock's work was richly textured and tightly structured with webs of dark paint, Frankenthaler's style was to become all about airy color and atmospheric space. In both their expression and method, her early 1950s works marked a new departure into the second wave of the movement. Washington Color School painter Morris Louis famously described this iconic painting as a "bridge between Pollock and what is possible."

Oil and charcoal on canvas - National Gallery of Art, Washington, D.C.

Black Still Life

A grid-like formation underlies this painting by Grace Hartigan, which references objective reality through carmine blocks resembling plant pots and shades of green reading as plants. They are arranged on the same plane, like on a table. In this artwork Hartigan brought the legacy of Abstract Expressionism - the use of layered, rough swirls of paint, the showcasing of brushstrokes and texture - in contact with the still life tradition. The affinity between Abstract Expressionism and another painting tradition, landscape, had been explored by painters such as Mitchell and Frankenthaler. Hartigan's work demonstrates another possibility of the Abstract Expressionist style in its second phase.

Born in 1922, Hartigan was first taken by Abstract Expressionism through the work of Jackson Pollock, which she saw in an exhibition in 1948. Departing from Pollock and the Greenbergian critical orthodoxy that had made his career, however, Hartigan was eclectic in her approach to subject matter, embracing modern life and its representation even as she experimented with shifting between abstraction and figuration. "I want an art that is not 'abstract' and not 'realistic,'" she wrote. At a time when male painters dominated the art world, Hartigan exhibited under the name "George" in the early 1950s, an homage, she said, to the writer George Eliot. But the name also allowed her work to be taken seriously by critics. Along with other women painters, Hartigan was at the vanguard of a rising tide in the art world that was slowly opening up to more diverse viewpoints and art styles in the 1960s.

Oil on canvas - The University of Arizona Museum of Art

Beginning

In this immediately arresting image Kenneth Noland plays with the "Target" motif that would occupy much of his mature art. A series of concentric circles in bold, contrasting colors create a lively optical effect as each circle seems to recede or move forward in space, drawing our eyes in. Painterly brushstrokes are left visible to lend the artwork an improvised, spontaneous spirit, while the outer rim is an energized swirl painted to appear as if moving round in space.

Noland began his career as an Abstract Expressionist painter, but his introduction to the work of Helen Frankenthaler in 1953 moved him towards a greater appreciation of color and space. He started to explore how ambient patterns and vivid hues could invest his canvases with the expansive qualities of light and air. To achieve this weightless quality, Noland worked directly on raw canvas, a process he took from Frankenthaler. Like Frankenthaler, Noland saw this method as an immediate, improvisatory act in which every move counts, famously calling himself a "one-shot painter."

Like other artists associated with late-phase Abstract Expressionism, Noland's circular motifs made reference to the exterior world, suggesting military targets, the Cold War, and the space race. Art historian Paul Hayes Tucker argues that Noland's art was one "for the atomic age, pulsating with explosive power yet emanating uneasiness." With their exploration of modern signs and their meanings rendered in an ultimately abstract language, Noland's "Targets" bridge a gap between Abstract Expressionism and the rising styles of Neo-Dada and Pop Art by artists such as Jasper Johns, Robert Rauschenberg and Robert Indiana.

Magna on canvas - Hirshhorn Museum and Sculpture Garden, Washington, D.C.

Rock Bottom

A wild tangle of energized color, Rock Bottom is dominated by thick streaks of cobalt blue that form a messy pool of darkness in the centre. The initial chaos of the image slowly reveals a sense of underlying structure over time, as sharp edges and hard angles gradually emerge from the wilderness like craggy rock edges or cliff faces, before dissolving back into the chaos.

Joan Mitchell made this painting while she was living in Long Island, New York in the summer of 1960. Rich, electric hues of blue began to appear in her work during this time, likely a reference to the vivid colors of the Long Island shoreline. Mitchell drew references to the exterior world back into an Abstract Expressionist language by filtering images of landscapes through her own subjective interpretations. Writing about this particular painting, Mitchell once said, "It's a very violent painting... And you might say [that about] sea . . . rocks." Her work also typified the second-phase of Abstract Expressionism with a fluid and instantaneous approach that echoed Kenneth Noland's "one-shot" attitude to making art.

French critic Pierre Schneider praised Mitchell's ability to create images that teetered between states of control and chaos, praising her first solo exhibition in Paris in 1960 for its "conflicting hesitations and mutually abolishing decisions."

Oil on canvas - Blanton Museum of Art, The University of Texas, Austin

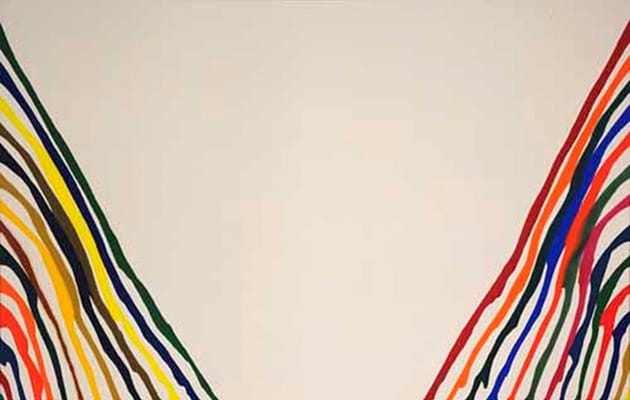

Beta Lambda

Rainbow streaks of color drip in waves down each side of the canvas, forming a near symmetrical motif with a great chasm of wide-open space in the center. Like many painters of his generation, Morris Louis was concerned with the relationship between vivid, intense colors and how they could invoke sensations of freedom and space within the painted pictorial field.

The "Unfurled" series are immense in size. Morris worked on them when he was making art in the dining room of his small home in Washington, D.C. The works were made on rolls of canvas that could not be fully unfurled in this small space, hence the title of the series. Their epic scale also made it difficult for the paintings to fit in many gallery spaces, hence only two of the paintings in a series of over 100 works were exhibited during his lifetime.

In the early 1950s Morris saw the art of Frankenthaler and was inspired to experiment with a new process of using liquid paint and a semi-controlled pouring process in which he tipped his canvas upright and allowed paint to run in ribbons and rivulets down its surface. The resulting works featured striped bands of ambient, atmospheric colors, which were placed in playful arrangements that let them bounce off and respond to one another. In works such as this one he took the spontaneity of Abstract Expressionism in a new direction, carefully balancing the application of color by a process that was controlled yet ultimately defined by chance.

Synthetic polymer paint on canvas - Museum of Modern Art, New York

Fatal Plunge Lady

Color is the defining feature of this expansive canvas that is almost entirely eclipsed by a glowing orb of radiant red, tingled with lilac in the center. Small accents of turquoise blue and purple hover in the far-right corner, adding a sense of space and weightlessness to the entire canvas. Art critic Roberta Smith describes this painting as "a burnt orange astral body orbited by a tiny red satellite, buffered by a patch of green."

Influenced by Mark Rothko and Helen Frankenthaler, New York-based artist Jules Olitski began making "stained" paintings in the early 1960s, infusing diluted paint into raw canvas and allowing it to soak deep into the core of the surface, where it could create tactile, painterly blooms, as can be seen in this work. The process allowed him to create a sense of light, depth, and space in his work, a quality that typified the Color Field painting style. Art critic Clement Greenberg praised Olitski's works for their emphasis on the formal, modernist properties of scale, color, atmosphere, and drama, at one point describing Olitski as "the best painter alive."

Although almost entirely abstract, Olitski's art often made oblique reference to the female body, with the use of curvaceous, voluptuous shapes suggesting of body parts . Titles, too, play a role, such as this work he called Fatal Plunge Lady. This reference point allowed Olitski to tie his art to the great masters of the past, from Rembrandt to Rubens, but it also betrayed the macho, male gaze that was still so prevalent in art practices of the time.

Acrylic on canvas - Estate of Jules Olitski

Icarus

Energized, rhythmic marks form a blizzard of colorful pattern across the entire canvas, allowing it to pulsate with energy and life. Dark, calligraphic lines are scrawled across the surface like an illegible form of handwriting, evoking a spontanoues, personal language of self-expression. The hot coral and fuchsia pinks in this work typify Krasner's mature works, which are characterised by shockingly bright, high impact color schemes.

Krasner made this work in the mid-1960s, after she had moved into her late husband Jackson Pollock's large barn studio to paint. Following his death in 1957, grief often kept her up at night. She turned to art, and it gave her a sense of drive and purpose. The vast space gave her room to branch out in new directions both literally and figuratively. She was known to work by jumping in the air with long handled brushes to reach the far corners of her largest works. Much like the earlier Abstract Expressionists with whom she was closely involved, Krasner worked intuitively on these canvases, allowing their forms and patterns to emerge organically. She observed of her working method, "There's a blank, and something begins to happen, and the hope is that it comes through."

Even when Abstract Expressionism had seemed to run its course, Krasner kept the flame burning for a little while longer with her unique visual language. As art critic Adrian Searle points out, "for Krasner the gesture wasn't spent. These stampedes and blizzards have a percussive, Stravinsky-like rhythm."

Oil on canvas - Pollock-Krasner Foundation

Beginnings of Abstract Expressionism: Second Generation

The first generation of Abstract Expressionists rose to fame in New York in the 1940s. They responded to the trauma of war with a bombastic, all-encompassing art filled with emotional grit and angst. By the 1950s their macho, aggressive style of painting had reached its zenith, culminating in worldwide prominence for the movement's star players including Jackson Pollock, Willem de Kooning and Mark Rothko, placing New York and the United States at the center of the modern art world.

Artists emerging in the wake of these giants faced a great challenge in attempting to move beyond or upstage their methods for making art, which tore apart pictorial conventions with "all-over," decentralized compositions, making it almost impossible to put them back together again. Kenneth Brummell, curator at the Art Gallery of Ontario, explains: "Pollock destroyed assumptions about painting - the generation of artists that followed were forced to contend with his innovations." The art that arose after Pollock, Rothko and de Kooning was more splintered and complex, encompassing a wider pool of artists from across the Unites States and beyond.

Greenberg and the “Tenth Street Touch”

A long-time champion of the first-generation Abstract Expressionists, New York-based art critic Clement Greenberg kept a watchful eye as expressive, painterly forms of abstraction evolved across the United States. His assertive voice would prove instrumental in defining the second generation of Abstract Expressionists that followed. He was deeply critical of the many younger artists who congregated around de Kooning's tenth street studio in New York, noting how their attempts to emulate de Kooning were becoming ever more self-consciously stylized and derivative, scornfully labelling their approach as the "tenth street touch." He observed how "Painterly abstraction has collapsed, because in its second generation it has produced some of the most mannered, imitative, uninspiring and repetitious art in our tradition."

The artists from New York that did successfully move beyond the mannered styles of expressionism were a less coherent group, and their art was more individualized and biographical in content than the first generation. Many women artists rose to prominence, such as Pollock's wife Lee Krasner, who became remarkably prolific in the years following Pollock's death, and Joan Mitchell, who was closely involved with the male-led first generation of Abstract Expressionists in her early career, before living out her later years as an abstract painter in France.

Greenberg and Color Field Painting

Greenberg was critical of the impasto effects that resulted from the application of thick paint layers in the work of many Abstract Expressionist painters in the 1950s. He likened their effects to that of a sculpture, rather than a painting, and so their appearances contradicted his championing of medium specificity. Instead, Greenberg increasingly turned his attention towards the sublime Color Field approach to painting opened up by Mark Rothko, Barnett Newman, and Clyfford Still, celebrating their ambient, emotive approach to color applied in broad, unmodulated surfaces. He particularly praised their flat surfaces, which erased the self-conscious, labored, or overworked touch of the human hand, liberating the canvas to become an arena filled with space and air.

Greenberg expanded his ideas in a series of hugely influential texts, including the essays "American-Type Painting (1955)," and "Modernist Painting (1961)," which both advocated for the idea of painting as a pure, autonomous art form that should relate only to itself, making no allusions to the outside world. The artists he praised in these essays were all developing atmospheric Color Field approaches to painting.

Beyond The New York School: Washington, DC and San Francisco

Throughout the 1950s both Washington, DC. and San Francisco became lively hubs for second-generation Abstract Expressionists. New York-based painter Helen Frankenthaler was particularly influential on a group of artists in Washington, DC. led by Kenneth Noland and Morris Louis, who developed her languid, painterly washes of color in daring new directions, further simplifying and refining her late Abstract Expressionism into a geometric, ordered language that would become known as the Washington Color School, a variant of Color Field painting. The Greenberg-curated exhibition Three New American Painters: Louis, Noland, Olitski (1963) at Norman Mackenzie Art Gallery in Regina, Canada represented his critical stance in their support. Greenberg argued that their art put "the main stress on color as hue [...] harking back in some ways to Impressionism, reconciling the Impressionist glow with Cubist opacity."

On the West Coast, artists Richard Diebenkorn and David Park were key figures in the San Francisco scene. Much like de Kooning and Guston in New York, both Park and Diebenkorn began introducing figuration back into their expressive paintings throughout the 1950s in a style that would become known as the Bay Area Figurative Movement. Even so, many artists within the Bay Area continued to practice in an Abstract Expressionist style throughout this period and beyond as a friendly form of rivalry to their figurative counterparts. The area was particularly notable for its openness towards women and minority artists, which stood in stark contrast to New York's original machismo.

Women Artists

If the first generation of Abstract Expressionists was largely dominated by a core group of white male artists centred around New York's Greenwich Village, various women artists stepped forward into the limelight as the second generation emerged, injecting a much-needed boost of life into the language of expressive abstraction. Jackson Pollock's wife Lee Krasner was associated with the earlier Abstract Expressionists throughout the 1940s, but her career only really took off after his death in 1956. She moved into Pollock's famous studio in their shared house in Springs, Long Island, and began painting through the night as a way to cope, producing vastly-scaled canvases that reflected on the sudden shock and isolation of her new life. "Painting was her antidote to grief," said curator Helen Harrison, today's director of the Pollock-Krasner home.

American painter Joan Mitchell had also been an active member of the New York school, but her career took off only in the early 1950s following a series of successful solo exhibitions in New York. Like several second-generation Abstract Expressionists, Mitchell's work moved beyond the expression of internal angst toward externalizing memories of time and place. As she once explained it, "I paint from remembered landscapes that I carry with me - and remembered feelings of them, which of course become transformed."

Other prominent and fearless women artists associated with the emergence of late Abstract Expressionism in New York included Jay DeFeo, Helen Frankenthaler, Grace Hartigan, Nell Blaine, Jane Freilicher and Elaine de Kooning.

Post-Painterly Abstraction

In 1964 Greenberg curated the exhibition Post-Painterly Abstraction at the Los Angeles County Museum of Art (LACMA). He included 31 artists in the show, the most prominent and celebrated figures being Frankenthaler, Jack Bush, Morris Louis, Jack Youngerman and Kenneth Noland. The exhibition made a clear divide between earlier, painterly styles of gestural abstraction and more recent developments, which (although diverse) all moved away from expressionist brushstrokes, including the Washington Color School, Bay Area artists, hard-edge abstraction, lyrical abstraction and Color Field Painting.

Greenberg's distinction between first- and second-generation Abstract Expressionism highlighted how the second generation had shifted from an interior, subjective view to a more externalized language, exploring how deeper meaning can be found in the objective world. The exhibition can be understood as Greenberg's defense of abstract painting against the tide of time. It came at a moment when new styles of art such as Neo-Dada, Pop Art, and Performance Art all aimed to to bring art closer to life, threatening to engulf the art of medium purity on which he had built his entire career.

Concepts and Styles

Art & Ideas:

Color Field Painting

The Color Field strand of Abstract Expressionism led by Mark Rothko, Barnett Newman, and Clyfford Still was hugely influential on a new generation of painters coming out of New York throughout the early 1950s. Greenberg's influential exhibitions and essays did much to promote this new branch of abstraction, which he saw as the logical next step in a steady progression towards pure, autonomous painting. The most prominent of these artists were Helen Frankenthaler and Jules Olitski. In contrast with their predecessors, their art was more vivid and intense, focusing on the ambient and emotive properties of saturated hues, which they bled into large, expansive surfaces resulting in amorphous abstract shapes. The gesturalism of earlier Abstract Expressionism was largely abandoned in Color Field painting, allowing unmodulated passages of color to take center stage. Frankenthaler had a breakthrough moment with her iconic painting Mountains and Sea (1952), in which she poured diluted, watery paint directly onto raw and unprimed canvas that she had laid flat on the studio floor, letting it pool and soak into the weave of the fabric surface. This so-called "soak-stain" approach merged the floor-based action art of Pollock with the sublime, atmospheric color of Rothko, heralding a new breakthrough in abstract painting.

Olitski, too, experimented with expressive and spontaneous paint applications, playing with spray guns and layering different paint viscosities from thin hazy washes to thick, impasto textures. Underpinning his practice was an acute awareness of color and its arresting impact. He wrote, "Color in color is felt at any and every place of the pictorial organisation; in its immediacy - its particularity. Color must be felt throughout."

The Washington Color School

Throughout the 1950s various artists in and around the Washington, DC area advanced abstract painting in new directions, exploring the spatial and non-gestural properties of color opened up by New York's Color Field painters. Leaders in this new style were Kenneth Noland and Morris Louis, while others associated with the style included Sam Gilliam, Gene Davis, Howard Mehring, Tom Downing, Paul Reed, Alma Thomas and the sculptor Anne Truitt.

Both Louis and Noland had painted in an Abstract Expressionist style in the 1940s, which attracted the attention of Greenberg. When Greenberg introduced them to Frankenthaler's work in 1953, Noland and Louis began adopting variations of her "soak-stain" method of painting in their practices. For Louis, color was a driving force, applied in vivid rainbow stripes that sometimes bled seamlessly into one another. Louis found his signature style by pouring diluted passages of bright magna paint (a type of acrylic resin paint known for its glossy finish) on a flat surface and tilting it up to allow the paint to run in rivulets down the surface. The new method merged the same qualities of systematic control and unpredictability as Frankenthaler's. Noland, too, adopted the "soak-stain" technique as a means of imbuing large areas of atmospheric, expansive color into his surfaces. His trademark "Target" paintings from the 1950s and beyond explored how radiating disks of vivid color could create the sensation of infinite, endlessly regenerating open space.

An exhibition in 1965 at the Washington Gallery of Modern Art titled Washington Color Painters organized by gallery director Gerald Nordland cemented the Washington Color School as a significant new art movement.

The San Francisco School of Abstract Expressionism

Within the San Francisco Bay area, a branch of Abstract Expressionism had flourished throughout the 1940s as a rival to the New York School, and Abstract Expressionist approaches continued to prove popular in the area throughout the 1950s. The San Francisco Art Institute played a pivotal role in fostering an innovative and open-minded environment with faculty members including Mark Rothko, Ad Reinhardt and Clyfford Still in the 1940s. Still became head of the graduate painting programme at the Institute in 1946, where he remained for four years. His influence galvanised Abstract Expressionist practices within the area for a new and upcoming generation.

Many artists were drawn to the Bay area, which became an alternative hub to New York. The artistic environment here was markedly different from New York; with few commercial galleries available, artists were less competitive, allowing for a supportive sharing of ideas. Art historian Susan Landauer describes the San Francisco attitude as one of "broad collective impulse" as opposed to the macho, ego-driven attitudes of New York. The area's Beat poets, Dixieland jazz musicians and the breath-taking scenery also shaped a particular spirit of expressionism within the area. Leading practitioners to emerge from San Francisco throughout the 1950s include Edward Corbett, Jay DeFeo, James Budd Dixon, Frank Lobdell and Hassel Smith.

A Return to Realism

Throughout the later years of Abstract Expressionism, various artists who had focused exclusively on abstraction began re-introducing elements of representation back into their practices. In New York, Willem de Kooning's infamous "Woman" paintings of the 1950s caused quite a sensation among critics and painters more accustomed to seeing his abstractions, because it disrupted the supposed narrative of reductive abstraction laid out by Greenberg. (Although he had been subtly switching between abstraction and figuration since the 1930s, his "Woman" paintings made a distinct move into directly figurative forms, setting this phase of his art apart from his earlier abstract style). Philip Guston, by comparison, had pursued an entirely abstract language throughout the 1940s, but he gradually changed tack, slowly bringing recognizable shapes and forms into his art before going full throttle in the 1960s with cartoon-like characters playing out overtly political scenarios. Greenberg was critical of Guston's "more coherent illusion of three-dimensional space," and the "tangible representation of three-dimensional objects," because they broke from his notion of modern art as a steady march towards medium purity. Harold Rosenberg, by contrast, continued to support the rising strands of representation within the style of Action Painting that he had championed in 1952.

Within the San Francisco Bay area, the renowned abstract artists David Park and Richard Diebenkorn spearheaded the Bay Area Figurative Movement from around 1949 onwards as a rival to the region's dominant strand of Abstract Expressionism, with crudely painted figures combined with slabs of vivid, intense color. Other artists who followed their lead included Joan Brown, Manuel Neri, Nathan Oliviera, Paul Wonner and Elmer Bischoff. The movement was a powerful counterpoint to Greenberg's narrative of formalist abstraction. Park, Diebenkorn, and Bischoff responded intuitively to their surroundings with a free, painterly language, capturing the distinctive light and color of San Francisco. Bischoff pointed out how their expressive figuration marked the end of Abstract Expressionism, which was "playing itself dry," adding, "I can only compare it to the end of a love affair."

Later Developments - After Abstract Expressionism: Second Generation

The influence of late Abstract Expressionism on international art trends was far-ranging, splintering into various divergent factions from the 1960s onward. The strand of Color Field abstraction practiced by Frankenthaler and the Washington Color School undoubtedly paved the way for the Hard-Edge Abstraction of Frank Stella and Ellsworth Kelly, who rejected painterly gesturalism in favor of impersonal fields of clean, flat color and geometric, systematic designs.

These ideas in turn helped shape Minimalist art from the mid-1960s onwards throughout the United States and Europe. Various artists including German artist Blinky Palermo and Americans Richard Tuttle and Robert Ryman explored the sensuous language of color and texture that was borne out of late Abstract Expressionist ideas but rendered them in a "cleaner," more geometric form in keeping with a Minimalist gravitation toward simplification. The idea of color as an ambient, atmospheric experience was taken further by various light artists, including Dan Flavin and James Turrell. The systematic approach to painting in Frankenthaler and Louis's practices continue to influence artists today, as seen in Scottish artist Calum Innes's stripped back "un-paintings," and British painter Ian Davenport's slick, glossy stripes made from poured gloss paint.

In New York, Contemporary Realism emerged in the 1960s as a reaction against Abstract Expressionism, with artists painting cool, detached observations of ordinary life. Several artists associated with the style, including Nell Blaine and Jane Freilicher, began their careers as Abstract Expressionists before adopting an increasingly figurative language, yet certain qualities of Abstract Expressionist art were carried forward, including flat areas of color and large, expansive canvases.

The idea of Action Painting (the critic Harold Rosenberg's term for Abstract Expressionist work) provided a springboard for the new generation toward inclusion of everyday life and more explicit political messages in their art. As early as 1958, Kaprow understood this implication in his insightful essay, "The Legacy of Jackson Pollock." Rather than an arena for inner subjectivity expression, Action Painting was re-styled as a form of event in the Neo-Dada and Performance Art of various practitioners in New York, particularly Karpow's own experiential "happenings" in the 1960s, and the important Body Art of Feminist movements that came afterwards.

In the 1980s, Neo-Expressionists such as Julian Schnabel and Georg Baselitz popularized a self-consciously ironic form of figurative expressionism, and, in recent years, an upsurge of figurative painting has seen similar styles appearing throughout the international art world, from the erotic bodies in the art of Cecily Brown to the stains and haunting distortions of bodies in the work of Marlene Dumas.

Useful Resources on Abstract Expressionism: Second Generation

- Reading Abstract Expressionism: Context and CritiqueOur PickBy Ellen G Landau

- Abstract Art: A Global HistoryBy Pepe Karmel

- Abstract Expressionism (Themes and movements)By Katy Siegel

- Women of Abstract ExpressionismBy Joan Marter, Gwen F. Chanzit, Robert Hobbs, Ellen G. Landau and Susan Landauer

- American Abstract Expressionism of the 1950s: An Illustrated Survey With Artists' Statements, Artwork, and BiographiesBy Marika Herskovic

- The Bay Area School: Californian Artists from the 1940s, 1950s and 1960sOur PickBy Thomas Williams, with a foreword by Michael Peppiatt

- Colourfield Painting: Minimal, Cool, Hard Edge, Serial and Post-Painterly Abstract Art of the Sixties to the PresentOur PickBy Stuart Morris and Laura Garrard

- Three American painters: Kenneth Noland, Jules Olitski, Frank Stella

- Ninth Street Women: Lee Krasner, Elaine de Kooning, Grace Hartigan, Joan Mitchell, and Helen Frankenthaler: Five Painters and the Movement That Changed Modern ArtOur PickBy Mary Gabriel

- Lee Krasner: Living ColourBy Eleanor Nairne

- Joan Mitchell: Leaving America: New York to Paris 1958-1964Our PickBy Helen Molesworth

- Kenneth Noland: Paintings 1958-1989

- Morris Louis, the Complete Paintings: A Catalogue RaisonneOur PickBy Diane Upright

- Jules Olitski: Communing with the PowerOur PickBy Clement Greenberg

- Richard Diebenkorn: The Berkeley Years, 1953-1966By Timothy Anglin Burgard, Steven Nash, Emma Acker

- David Park: A RetrospectiveBy Janet Bishop

- Philip Guston RetrospectiveBy Ashton Dore, Michael Auping, Bill Berkson, Andrew Graham-Dixon, Joseph J. Rishel, Michael Edward Shapiro

Ask The Art Story AI

Ask The Art Story AI