Summary of Action Painting

The small, personal act of painting was not going to spark revolutionary change, but in the very act of carving out a space to engage in a creative dialogue with materials - paint and canvas - the artist registered an act of rebellion within the conformist culture of the Cold War. Coined by art critic Harold Rosenberg in 1952 as an alternative to Abstract Expressionism, Action Painting emphasized the revolutionary nature of the artist's decision to paint. Rosenberg elaborated on ideas of painting as an action he had heard in artists' studios and wove them with Marxist theory, Existential philosophy, and his thoughts on drama to articulate his description of the new American painting. What resulted on the canvas was, in Rosenberg's words, "not a picture but an event." Action Painters were not interested in depicting illusionistic scenes but rendering the energy and movement of life in a visible way on the canvas.

While typically associated with gestural painting, Action Painting was meant to encompass a wide array of artists, from Jackson Pollock to Barnett Newman, although the artists themselves shied away from adopting the moniker. While Rosenberg's friendly proximity with the artists gave him access to how the artists were talking about their painting, Rosenberg's theory of Action Painting was largely overshadowed by Clement Greenberg's more formalist readings of Abstract Expressionist painting. His description spawned many interpretations and misreadings, some of which came to fruition in later Performance Art, but many scholars have worked in recent years to rehabilitate Rosenberg's contributions to the understanding of Abstract Expressionism.

Key Ideas & Accomplishments

- One of the main tenets of Abstract Expressionism was the evasion of a collective style. Each artist painted in his or her own way, developing individual, signature styles. Recognizing this diversity, Rosenberg's emphasis on the process of painting instead of style allowed him to speak of the artists collectively in a way that highlighted their motivations instead of the way their paintings looked.

- Action Painting is predicated on the idea that the creative process involves a dialogue between the artist and the canvas. Just as the artist affects the canvas by making a mark on it, that mark in turn affects the artist and determines the trajectory of the next mark. As Rosenberg explained, "Each stroke had to be a decision and was answered by a new question." While spontaneity is key to Action Painting, it is always within the parameters of this dialogue.

- Rosenberg linked Action Painting with the artist's biography, but he was careful to point out that he did not mean that we should scrutinize the painting to find references to the artist's private life or to find clues about the artist's psychological state. Instead, Rosenberg meant something more existential in the sense that in painting the artist was not necessarily expressing the self but creating the self.

Artworks and Artists of Action Painting

Autumn Rhythm (Number 30)

Many scholars speculate that Jackson Pollock was Rosenberg's primary model for his description of Action Painting, although equally good arguments have been made for other artists as well. Even if he was not the chief artist Rosenberg had in mind, Pollock's paintings have become synonymous with Action Painting. Autumn Rhythm is a quintessential drip painting, with its all-over composition of a dizzying web of black, brown, and white enamel paint.

To execute this work, Pollock laid out a large unstretched canvas on the floor of his studio, and then, walking around the four edges of the canvas, he systematically poured, dribbled, and flung paint across its surface. In one of his rare written statements, Pollock explained, "When I am in my painting, I'm not aware of what I'm doing. It is only after a sort of 'get acquainted' period that I see what I have been about. I have no fears about making changes, destroying the image, etc., because the painting has a life of its own. I try to let it come through. It is only when I lose contact with the painting that the result is a mess. Otherwise there is pure harmony, an easy give and take, and the painting comes out well."

Pollock's particularly performative way of painting is of course more active than most painters', but his ability to respond to new lines and forms as they emerge in the painting process speaks to his spontaneity and his engagement in a dialogue with his materials. While many scholars speak of Pollock's work as a metaphor for the unconscious - its inchoate skeins of paint suggesting the inchoate nature of our pre-conscious minds - in reality, Pollock's control and decision-making processes in the act of painting create a tension with that reading. It is, though, this very back and forth between painter and painting that was at the heart of Rosenberg's idea of Action Painting.

Enamel on canvas - The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York

Chief

Franz Kline's stark black and white compositions of bold brushstrokes make him one of the quintessential gestural Abstract Expressionists. The simplicity of the colors and means, though, belies the often complex compositions that balance strong verticals and horizontals, broken curves, and imperfectly formed roundels. Importantly, Kline does not just paint black strokes onto a white ground but also paints the white next to and on top of the black, setting up a beguiling tension between figure and ground.

Many of the Abstract Expressionists, including Kline, insisted that their paintings were spontaneous acts, without preplanning. While one might assume that this spontaneity means the paintings were done quickly in one sitting, the actual process suggests otherwise. Kline, in fact, was constantly drawing, making small, black ink drawings on any paper he could find, even thin telephone book pages. Some of his paintings are reminiscent of one or sometimes a combination of these drawings.

In his essay on Action Painting, Rosenberg recounts a conversation with an unnamed artist who complains that one of his colleagues - also unnamed - is old fashioned because he works from sketches, but Rosenberg counters this artist's protestation by saying, "There is no reason why an act cannot be prolonged from a piece of paper to a canvas. Or repeated on another scale and with more control. A sketch can have the function of a skirmish." Here, Rosenberg subverts the preconception that planning, or sketching, an idea before one goes to the canvas is anathema by arguing that there is no rule or formula about how long an action takes or that a painting is simply one action. Rosenberg's conception of Action Painting complicates notions of spontaneity, and Kline's Chief, when carefully studied, embodies that complexity.

Oil on canvas - The Museum of Modern Art, New York

Woman III

Willem de Kooning shocked the art world when he showed a Women series at the Sidney Janis Gallery in 1953. Many critics decried his "return" to the figure without understanding that de Kooning had always painted abstractly and representationally more or less at the same time. But even by this early date, Abstract Expressionism and Action Painting were yoked to abstraction, and the revelation of the figure in de Kooning's latest work seemed like an affront to avant-garde art.

De Kooning dodged accusations of misogyny by talking about his Women as modern equivalents of ancient idols and trying to point out the humor in his representations. The controversies of subject matter aside, Rosenberg certainly would have counted de Kooning among the Action Painters, as Action Painting had little to do with subject matter and most to do with the artist's attitude toward painting. In describing abstract painting, Rosenberg wrote, "The apples weren't brushed off the table in order to make room for perfect relations of space and color. They had to go so that nothing would get in the way of the act of painting." De Kooning was a rare artist who was able to meld the modernist insistence on materiality and flatness with a recognizable subject matter in his act of painting.

In an undated note, de Kooning wrote, "With intimate proportions I mean the familiarity you have when you look at somebody's big toe when close to it, or a crease in a hand or a nose - or lips or a ty [thigh]. The drawing those parts make are interchangeable one for the other and become so many spots of paint or brushstrokes." Body parts for de Kooning are less about their representational function and become instead abstract, malleable forms and bits of paint to be put together like any geometric shapes or colors. Furthermore, de Kooning's willingness to buck the strictures that avant-garde art has to be abstract made him more original than most in Rosenberg's estimation. As he told the art critic David Sylvester, "It's really absurd to make an image, like a human image, with paint today, when you think about it, since we have this problem of doing or not doing it. But then all of a sudden it was even more absurd not to do it. So I fear that I'll have to follow my desires."

Oil on canvas - Private Collection of Steven A. Cohen

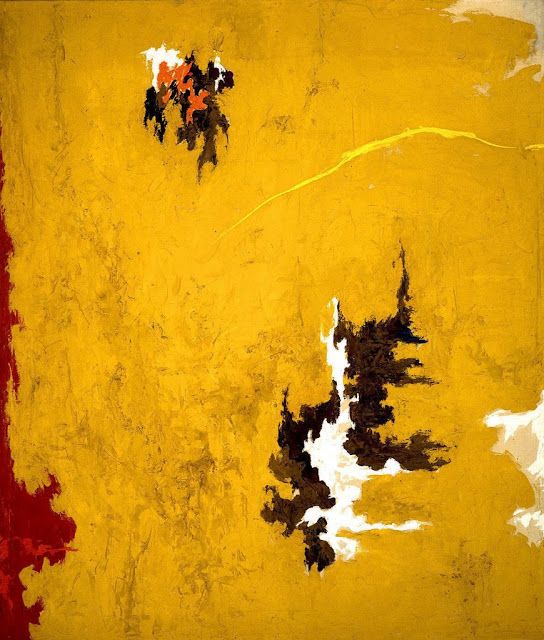

No. 3

In a provocative 1958 article, painter and critic Elaine de Kooning declared both Franz Kline and Mark Rothko American Action Painters. While most would readily concede that Kline is an Action Painter, with his gestural compositions, most have not considered Rothko or other Color Field painters as Action Painters. This oversight, however, misses one of the key aspects of Rosenberg's Action Painting. As Elaine de Kooning puts it, "What distinguished these Americans was the moral attitude which they shared toward their art; that is to say, they saw the content of their art as moral rather than aesthetic."

If one looks long enough and closely enough, one sees the layers, the strokes, the dribbles of paint that Rothko employed to create ethereal, intimate paintings. In choosing to paint instead of entering into some other profession, Rothko was committed to declaring his own self - whatever that might entail - in his painting. Action Painting always carries with it an existential stance; they are, in de Kooning's words, "an extension of [the artist's] life."

In wanting to evoke a range of human emotions, this moral dimension of the act of painting also carries over to the act of viewing. Rothko was particularly sensitive to the installation of his works: how high or low they hung on the wall, their proximity to one another, the lighting in the gallery. Additionally, the scale of painting was crucial, as he explained that he painted large paintings precisely because he wanted "to be very intimate and human." In attempting to make a direct and physical relationship between the painting and the viewer, Rothko hoped that the viewer might also experience her own existential being. As he said, "I take the liberty to play on any string of my existence. I might, as an artist, be lyrical, grim, maudlin, humorous, tragic. I allow myself all possible latitude. Everything is grist for the mill." He hoped the viewer would recognize the same.

Oil on canvas - The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York

Untitled

Around 1950, Joan Mitchell moved to New York City to pursue her painting career and fell in with the Abstract Expressionists working and hanging out near Greenwich Village. Usually dubbed a "second generation" Abstract Expressionist because of her age, Mitchell's evocative gestural abstractions stand up to any of the paintings done by the first generation. While she gained early acclaim among critics, her gender kept her on the periphery of narratives of Abstract Expressionism. And while Action Painting is often caricaturized as being involved in heroic masculinity, Mitchell's paintings show that masculinity in and of itself has little to do with Action Painting.

In "The American Action Painters," Rosenberg wrote, "A painting that is an act is inseparable from the biography of the artist." Rosenberg did not mean that one should read the painting as clues to the artist's biography or psychological state. He went on, "The painting itself is a 'moment' in the adulterated mixture of his life - whether 'moment' means the actual minutes taken up with spotting the canvas or the entire duration of a lucid drama conducted in sign language." In Mitchell's Untitled, one gets a sense of this unfolding drama with the amalgamation of strokes and colors. Layering vertical and horizontal strokes of various colors, Mitchell creates an all-over composition, although the strokes are densest in the central part of the canvas. Within the dark browns, blacks, and gray, strokes of red and blue activate the center. One has the vaguest sense that forms, maybe even figures, seem to want to coalesce but just as quickly dissolve, never quite coming together in a recognizable form.

Mitchell often read poetry or listened to music while she prepared to paint. The emotions aroused in these activities combined with her memories, long past and current, to create dynamic compositions. As the Joan Mitchell Foundation website explains, "Mitchell's process is informed by a range of emotional states, points in time, and positions in landscape, and her work is an affirmation that people experience landscapes, emotions and memories in a complex, interconnected way." This is precisely the adulterated, messy life that Rosenberg speaks of in describing the source of Action Painting.

Oil on canvas - Collection of the Joan Mitchell Foundation, New York

La Garrigue

Fautrier's La Garrigue demonstrates the close relation of European Tachiste painting to the contemporaneous, American mode of Action Painting. The French word tache means spot or splash, and Tachisme paintings tend to be expressionistic and gestural like much Abstract Expressionist art, but perhaps a little more polished-looking. In La Garrigue, which means scrubland, Fautrier focused on one central area of dry, densely-applied paint, suggesting a compositional device that was absent from the "all over" appearance of much New York School painting from this time. Fautrier creates a relationship between a "ground" - the murky blue edges of the work - and a "figure" - the compact sweeps of green paint at the center of the work. This thick crust of paint on the work's surface reveals the sweep of Fautrier's brush, registering the artist's creative gesture. Indeed, one infers from the paint a fraught gesture, full of nervous energy. Despite the work's allusion to landscape, the paint itself takes on the role of subject-matter, and one is invited by Fautrier to address both the paint surface and his act of making as topics of interest.

In his seminal text of 1952, Un Art Autre (An Other Art), the French critic Michel Tapié identified Fautrier as a precursor to Tachisme and Art Informel, a broader category that included a variety of abstract painting that pushed traditional boundaries. One especially French aspect to Fautrier's Tachiste mode of Action Painting is, as scholar Sarah Wilson has described, his concept of "the work as dureé", or "duration" - the notion that a work reveals itself as physical activity enacted over time. La Garrigue's involved sweeps of thick paint register the motion of the artist's hand, and it contributes a vivid, pessimistic flavor to the wider array of Action Painting being made in the years after the Second World War.

Oil on paper mounted on canvas - Museé d'Art moderne de la Ville de Paris, Paris

Mr. Stella

Kazuō Shiraga made this brash, heavily worked painting with his feet. By attaching a rope to the ceiling of his studio, Shiraga was able to suspend himself over paper laid on the floor. From there he proceeded to sweep his paint-covered feet over the canvas. This method removed a degree of control from the artist. While our hands are dexterous and capable of finely nuanced manipulations of paint, our feet are clumsy and give an imprecise finish. It was Shiraga's intention, therefore, to make himself a hostage to the accidents of a less controlled process.

Mr. Stella is composed of a dense, messy ground of reddish brown paint, inconsistently applied and not reaching to the edges of the paper. Into this ground Shiraga has made some approximate sweeping motions with his feet, and a number of arcs and circles can be seen. No single element of the painting stands out, and it is apparent that he was working wet paint into wet paint, adding new layers of paint when lower layers had not yet dried, thus disturbing each layer as he worked.

The artist's decision to use his feet instead of his hands reveals a desire to explore a more involved, physical way of painting. Mr. Stella has significant relationships with other key moments in the history of Action Painting, and the decision to work on the floor suggests an obvious debt to Jackson Pollock. When the Art News article "Pollock Paints a Picture," illustrated with photos by Hans Namuth of Pollock painting, made its way to Japan, avant-garde Japanese artists took note. More than their American counterparts, the Japanese artists took the process and materiality of Action Painting (Gutai means "concreteness") to new levels.

The painting's title also refers to another American artist, Frank Stella, a seemingly unusual reference to a Minimalist artist who would seem to be on the opposite end of the spectrum of Abstract Expressionism. Perhaps Shiraga took interest in Stella's recent engagement with a series of geometric black paintings that emphasized materiality and an almost mechanical process of making because of their concreteness. In addition, the artist's use of his body as a paintbrush prefigures the experiments of Yves Klein in 1960, who would use women's bodies as a paintbrush in his Anthropometries. Mr. Stella is an important and early instance of performance in art, where the event of making came to be of equal importance to the finished work of art itself.

Oil and Japanese paper on canvas - Osaka City Museum of Modern Art, Osaka, Japan

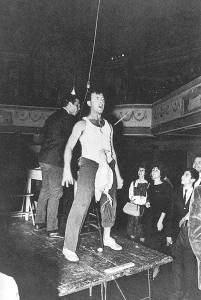

18 Happenings in 6 Parts

Obviously, a performance is not a painting, but Kaprow's "happenings", a term he coined for his performances, are deeply indebted to Jackson Pollock and ideas of Action Painting. This was one of the earliest and most significant of Allan Kaprow's happenings, held at the Reuben Gallery in New York in late 1959. Kaprow had introduced the idea of a performance-based art, drawing on commonplace materials, in an article from a year before called "The Legacy of Jackson Pollock." Kaprow felt that Pollock had taken painting as far as it could go, right up to the line where painting spills over the edges of the canvases, covering the remaining walls and entering into real life. Kaprow's happenings existed in real space, not the walls of the museum and gallery, and the present, the here and now. Remnants of Action Painting were present in 18 Happenings, with the gallery divided into three "rooms" by translucent plastic sheeting, which were collaged with painterly interventions. It should however be noted that Rosenberg felt that the move to performance-based art was a misreading of Action Painting, and he continued to insist that the autonomy of the painting itself was crucial.

While Action Painters were concerned with how viewers approached their paintings, Kaprow's happenings sought to collapse the hierarchy of artist and audience by loosening the artist's control of events and making the audience an active component in the performance. Kaprow was not alone in his performance - an ensemble was required for the musical and theatrical pieces that he programmed. What is more, the audience was issued a booklet of instructions on how to proceed through the performance. The booklet explained, "The performance is divided into six parts... Each part contains three happenings which occur at once. The beginning and end of each will be signalled by a bell. At the end of the performance two strokes of the bell will be heard... There will be no applause after each set, but you may applaud after the sixth set if you wish." Kaprow downplayed the artist's expressivity and intentional meaning and transformed the creation of art into a collective process.

First performed at the Reuben Gallery, New York

Beginnings of Action Painting

Forbears

The art historian Nicholas Chare has written that "the dynamics of action, as presented by Rosenberg, have visual precursors in art of the past." One might go back to Michelangelo's drawings or even Rembrandt's paintings, but more immediately, one can point to Manet and the Impressionists, who emphasized the physical process of painting by not hiding the brushstrokes that made up the surfaces of their paintings, and later, the Surrealists, who promoted automatic drawing that was not mediated by a conscious decision-making process.

Comparatively, a theory of sculpture emerged in the early 20th century that laid special emphasis on Direct Carving. From the 1910s onwards, the likes of Eric Gill and subsequently Henry Moore promoted the idea that carving and its visible effects were important to the finished work itself. These ideas were translated into compelling prose by the British artist and writer Adrian Stokes, whose book The Stones of Rimini was published in 1934.

Rosenberg, then, in emphasizing action elevated a certain quality of execution that was already present in the Western tradition of art. While Rosenberg did acknowledge that American abstract art may resemble European forebears, the American's motive for abstraction, their emphasis on process, was decidedly different and carried an existential, even moral, character.

Action Painting's Post-War Context

Rosenberg embraced the Marxist ideas that circulated among the Leftist intelligentsia and bohemia during the 1930s, and his friendships with important thinkers such as Hannah Arendt, her husband Heinrich Blücher, Paul Goodman, and Kenneth Burke likely informed his own thinking about individuality, agency, and action. It was during this time that he started meeting and hanging out with the artists who he would later write about. He was familiar with the earlier Dadaists who used their art to vehemently critique the culture and society that led to the First World War, and he heard artists like Herbert Ferber and Willem de Kooning talking about the canvas as an arena and painting as a struggle. In the face of a devastating war, an increasingly bureaucratized society, and an encroaching mass culture that promoted conformity over individual creativity, Rosenberg set out to probe the ways artists responded to this new era in their art. Originally written to introduce a European audience to the new post-war American painting, Rosenberg ended up publishing his essay "The American Action Painters" in the December 1952 issue of the prominent magazine Art News. He didn't mention any artists by name, but it was clear that he was speaking of the small group of vanguard painters in New York City.

Particularly after World War II, there was a growing sense that something new and wholly unrelated to the preceding "values" of art was required. While "The American Action Painters" is most famous for providing a description of Action Painting, one of its larger points is that in the wake of the commodification of Modern Art (he capitalizes this to distinguish it from art made in the modern era) and its uses and abuses by cultural elites, this new painting has not found a larger audience. In fact, with this newly debased, popular culture, in which art lacked substance and did not have an essential quality, Modern Art, in Rosenberg's estimation, could be attached as a superficial label to anything that struck one as being novel or unfamiliar. He was concerned that Action Painting had not been acknowledged for what it was - a profoundly physical assertion of human life in an increasingly dehumanized society.

Rosenberg and the painters he described were not only anxious to escape and surpass the precedents of European artistic achievements, they were also eager to transform the basis on which art itself was understood. Rosenberg distinguished between the merely visual nature of all preceding art, on one hand, and the action-led nature of Action Painting, on the other. At the centre of Action Painting was a desire for human life, the movement and gesture of the artist, to emerge as the primary point of interest in an artwork.

In one respect, Action Painting was a reaction to the dehumanising effects of mechanised warfare and the affecting consequences of participation in a bloody war. For Rosenberg, moreover, this assertion of human life also grew from the frustrations of economic stagnation. As the art historian Fred Orton described, since the Great Depression in the 1930s a "sense of impasse" developed among certain American intellectuals, who came to feel an acute need for radical change. Rosenberg was one of them, and for him, Action Painting was partly a way of expressing revolutionary political intent.

Contentious critics

Within the annals of Abstract Expressionism, Rosenberg's rival was Clement Greenberg, another prominent art critic who was one of the Abstract Expressionists' most important advocates. Greenberg's approach to the new American painting was formal; that is, he concentrated his criticism on painting's specificity. Greenberg contended that each art needed to focus on what made it unique; in painting's case, its flatness. Instead of representing, or illustrating, a three-dimensional world, painting should explore its own essence, its own two dimensionality. Greenberg imagined art's progress to be away from representation, as such, and towards greater abstraction.

While both championed abstract art, Rosenberg's formulation of Action Painting as an existential act might be regarded as a riposte to the formalism espoused by Greenberg. Rosenberg was less concerned than Greenberg with stylistic aesthetics or the progress of modern art, and his position among the artists put him closer in touch with how the artists spoke about their work. While Greenberg knew the artists personally and visited their studios, Rosenberg hung out with the artists in social settings such as The Club and the Cedar Tavern and was more ensconced within the group. This vantage point gave him a unique insight into the artists' motivations and helped him to formulate his idea of Action Painting, and in fact, much of what Rosenberg writes in the essay is an attempt to give voice to the artists themselves. In his telling, it was the act of making that counted, not the formal qualities of flatness, arrangement, line, and color.

Action Painting: Concepts, Styles, and Trends

Gesture Painting

Action Painting has become synonymous with the gestural painting of artists as diverse as Jackson Pollock, Willem de Kooning, and Franz Kline. Most typically, the action of Action Painting is associated with how the artist puts paint on canvas. The Abstract Expressionists were not using tiny brushes and delicately putting paint on the canvas. These gestural painters often used large brushes to make sweeping strokes across the canvas, and it was the action of that gesture, of moving not just one's hand but oftentimes one's entire arm, that came to define Action Painting in the popular imagination. The paint stroke is read as the index of the artist's movement.

The physical action of the painter is most famously illustrated in Hans Namuth's 1951 film and photographs of Pollock painting. We see Pollock moving around the edges of his canvas - sometimes even stepping into it - dipping a tool into the can of paint, and directing the paint onto the canvas by reaching his arm over the space and flicking the paint off of the brush. Pollock's skeins of dripped lines, flicked and splattered marks, and pools of paint invite a viewer to think about the actions that Pollock used to make them. The way the drip paintings were made is inseparable from the way they look.

Among many others, the output of Willem de Kooning, Robert Motherwell, Norman Bluhm, Franz Kline, and Hans Hofmann demonstrated highly individual styles all of which in some way drew attention to the act of execution - the sweep of a loaded brush for de Kooning, a wild splash of paint for Bluhm, a slash of black paint for Kline. In all these painters' work, the manner of execution became the content of the work.

Color Field Painting

The equation of gesture painting and Action Painting is largely a product of subsequent interpretations of Rosenberg's idea, and scholars and critics often overlook the fact that Rosenberg thought that artists such as Barnett Newman, Mark Rothko, Clyfford Still, and even Ad Reinhardt fell within the realm of Action Painting. While Clyfford Still would later repudiate Rosenberg's ideas of action, he himself often spoke of the act of painting. In 1952, the same year as Rosenberg's essay was published, Still wrote, "We are now committed to an unqualified act, not illustrating outworn myths or contemporary alibis. One must accept total responsibility for what he executes. And the measure of his greatness will be in the depth of his insight and his courage in realizing his own vision." Rosenberg's explanation of the American artists' motivations would echo Still's grand pronouncement.

The gesture that Rosenberg wrote about in his essay "The American Action Painters" is the initial gesture of putting paint on the canvas. As he explained, "The big moment came when it was decided to paint...just TO PAINT. The gesture on the canvas was a gesture of liberation...." For Rosenberg it was not essential that the paint on the canvas had to look gestural. In an extreme reading, almost any painting could be an Action Painting, and one of the most common criticisms of Rosenberg's idea is that one cannot judge an Action Painting based on how it looks but instead must infer the authenticity of the artist's intentions. Rosenberg, though, would not go so far as to claim Rembrandt or Monet as Action Painters, as he was specifically talking about a group of like-minded artists working contemporaneously in New York City.

Tachisme and the Second School of Paris

In their own response to the devastations wrought by World War II, European artists developed their own version of Abstract Expressionism, or Action Painting. Tachisme was a European movement in painting closely related to Art Informel and Art Brut and partially developed by the critic Michel Tapié. Like the New York School, the Second School of Paris included a variety of artistic interests. One prominent artist associated with the term, Jean Fautrier, used his canvases to suggest the texture of bodily suffering. Employing automatist methods, his paintings were often unplanned and look swiftly painted, concealing the involved technique he used. Another painter associated with Tachisme, Nicolas de Staël, sought to reconcile painterly abstraction with a suggestive kind of representation. His paintings from 1950 onwards demonstrate an increasing interest in the imminence of painting - the application of a loaded brush to canvas - while continuing to suggest the salient lines of a landscape, with foregrounds and horizons.

Gutai

In 1954, a short time after Rosenberg developed Action Painting in America, a group of Japanese artists clustered around Jirō Yoshihara in the small city of Ashiya, near Osaka. They were interested in creating artworks that made visible the act of making. Yoshihara had been an early pioneer of abstraction in Japan. Seeking to develop a more coherent school of painting, he paid for and led the foundation of the Gutai Bijutsu Kyōkai, the Concrete Art Association. Unlike the American Action Painters, Gutai was highly organized, publishing its own eponymous journal and holding regular group exhibitions. The leading contributors to the group were Kazuō Shiraga and Atsuko Tanaka.

As the 1950s progressed, proponents of this dynamic mode of painting become increasingly aware of connections between the American, Japanese, and European painters of the time. In 1958, a large exhibition of work from all three continents was held in Tokyo at the Takashimaya department store. The International Art of a New Era, partly curated by Michel Tapié, the leading critic of Art Informel in France, was a major milestone towards the international recognition of the Action Painting mode.

Later Developments - After Action Painting

After the initial generation of Action Painters, painters like Francis Bacon and Cy Twombly developed their own distinctive gestural styles. In his early paintings, Twombly in particular took the gesture of the Action Painter, sometimes thought of in terms of unique handwriting, and emptied it of its existential rhetoric and emotion. Countering the Abstract Expressionists' insistence on individuality, Twombly downplayed the role of the artist as original creator, highlighting the mechanical nature of writing in his chalkboard paintings and the anonymity of graffiti.

More generally, however, Action Painting was superseded by those artists who took the painters' rejection of Pictorialism one step further. Where Action Painting denied the importance of "the aesthetic," some artists claimed that there did not even need to be a remnant, or document, of the artistic act, emphasizing the centrality of the creative act in and of itself. In effect, Performance Art and its relatives took the "painting" out of Action Painting. Allan Kaprow's "happenings," sought to reject the materials of painting altogether. Kaprow wanted an art that was made from the stuff of one's immediate surroundings - not the abstruse confections of paint practised by Action Painting.

Yves Klein's early performances were highly significant in marking the deterioration of Action Painting's philosophy. His Anthropometries, staged in 1960 and using women as "living paintbrushes'" sought to remove the artist from any involvement with the application of paint but continued to develop Rosenberg's notion by explicitly revealing the process of making. Where Rosenberg asked audiences to think about a painting in terms of what the artist did in the privacy of the studio, Klein boldly stepped into the public gaze and made a very public demonstration of what went into the making of his work. Despite Rosenberg's subsequent criticism of performance-based art, which he took to be a misreading of Action Painting, Klein's innovations inspired a generation of artists and further directions in art marking.

Useful Resources on Action Painting

- Jackson Pollock: New ApproachesOur PickBy Kirk Varnedoe and Pepe Karmel

- de Kooning: An American MasterBy Mark Stevens and Annalyn Swan

- The Tradition of the NewBy Harold Rosenberg

- The Anxious ObjectBy Harold Rosenberg

- The De-Definition of Art: Action Art to Pop to EarthworksBy Harold Rosenberg

Ask The Art Story AI

Ask The Art Story AI