Summary of American Folk Art

American Folk Art is a rich, living tradition that runs alongside and feeds into the mainstream of North American art history. Since the early twentieth century, when the terms and ideas around the movement were defined, Folk Art has influenced modern painting, sculpture, architecture, and even music. The term is broad enough to incorporate the art of European settlers in the USA as well as North America's native populations, the descendants of enslaved communities transported from Western and Central Africa, emigres from the Caribbean, and more. Because it is not created by professional artists or "schools" of art, Folk Art is often celebrated for an “unselfconscious” quality that can make it wonderfully unique and surprising.

Key Ideas & Accomplishments

- Folk art is often the product of communities marginalized by mainstream culture by ethnicity, social class, poverty, or rural isolation. From Navajo rugs to Appalachian pottery, Folk Art reveals the experiences of communities and individuals who might otherwise lack a voice in the American story.

- Folk Art does not recognize academic distinctions between high art and functional craft. It often consists of utilitarian items such as furniture, cooking pots, and musical instruments and songs. As such, it allows us to appreciate the beauty of the humble objects and experiences that surround us in our daily lives.

- During the early twentieth century, Folk Art became hugely influential on the ethos of modern art, much of which was questioning and rejecting inherited traditions. This makes Folk Art central to the whole story of art in general.

- Folk Art is closely linked to the concept of Outsider Art, art created by individuals outside the conventional art world with unique ideas, techniques, and visions. In this way, Folk Art has played a major role in shaping today's contemporary art world, which often celebrates the position of the outsider.

Overview of American Folk Art

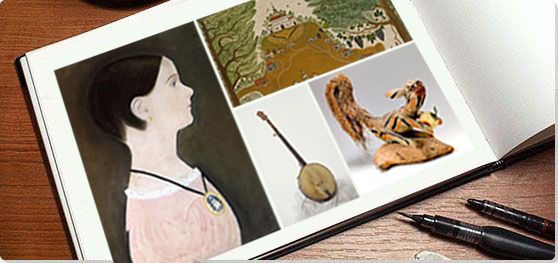

American Folk Art is art created by everyday Americans, without formal schooling, working outside the conventional art world. From intricate quilts to whimsical sculptures, this unique genre offers a fascinating map of the national psyche.

Artworks and Artists of American Folk Art

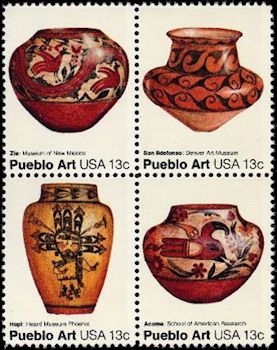

Ancestral Pueblo Flagstaff Black on White Double Jar

This ancestral jar exemplifies the craftsmanship of Pueblo (or Puebloan, a group of Native Americans in the Southwestern United States) pottery, featuring two rounded vessels connected by a central cylindrical bridge to create a unique form. Likely used for ceremonial or ritualistic purposes, the pot's surface is adorned with black geometric patterns on a white background, characteristic of the Flagstaff style. The designs, including interlocking rectangles, linear motifs, and symmetrical arrangements, are meticulously painted.

The shape and patterning of Pueblo pottery is not merely decorative. Often it symbolizes cultural and spiritual concepts related to cosmology, social organization, or agricultural cycles. The symmetrical design of the jar reflects a deep appreciation for balance and harmony, core values in Puebloan art and life. Its dual vessels indicate the symbiotic qualities of unity and duality. The care taken over the design of items like this one reflects the fact that the Pueblo people see their pottery as living beings, imbuing each piece with a sense of identity and spirit. This stems from their belief that pottery, like humans, originates from the earth, undergoing a transformative journey through crafting and firing which symbolizes the human life-cycle.

Clay, considered a sacred material, is gathered by the Pueblo from natural deposits near rivers or mountains. The pottery is often crafted using coiling, pinching, or molding methods, with designs inspired by nature and spiritual beliefs. During rituals, pots are used to hold sacred substances or offerings, embodying the connection between the physical and spiritual realms.

Ceramic - Heard Museum, Phoenix

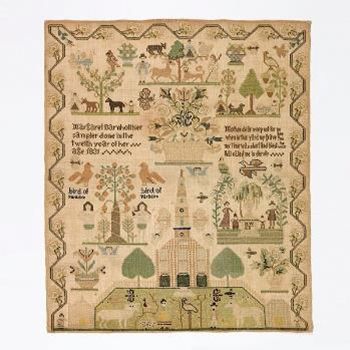

Bed rug

This bed rug from the Metropolitan Museum of Art's collection exemplifies a distinctive form within American Folk Art. The use of geometric patterns is typical of American bed-rug art, as is the central motif depicting a floral bouquet. Works of this kind often show the bouquet emerging from a small urn and reflect the influence of Indian Palampore textiles, which often feature a similar, “Tree of Life” image representing the vitality and interconnectedness of nature.

Bed rugs, known as "ruggs" in the late eighteenth century, were crafted in the family home. The construction technique involved needleworking piles of wool-yarn onto a base typically made of handloomed wool or linen. Often, the underlying blanket is entirely concealed by elaborate embroidery. The wool used for these rugs was typically sourced from local sheep, and underwent washing, carding, spinning, and dyeing all undertaken by the rug-maker. Distinguished by their bold, large-scale designs, bed rugs stand apart from other embroidered bed coverings. The use of thick sewing yarns and the necessity of effective pile designs required oversized motifs, enhancing their visual appeal.

What makes bed rugs fascinating is their regional diversity and the individuality of each piece. While sharing common techniques and motifs, bed rugs varied widely in design and execution based on the cultural and geographical context of their makers. However, they also reflect broader trends in American decorative arts, such as the influence of European and Indigenous designs adapted to suit American rural sensibilities.

Wool embroidered with wool - Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York

The Plantation

This work exemplifies several typical aspects of American Folk Art, including the use of intricate detail depicting rich social worlds and narratives. The composition has a symmetrical layout, and uses rich color. The central focus is a large mansion atop a hill, surrounded by smaller buildings and lush greenery. The scene is framed by two massive trees on either side, their canopies forming an arch that draws the viewer's eye towards the mansion. The lower part of the painting depicts a large sailing ship docked near the shore, indicating the mansion's connection to maritime activities.

The artist employs simplified shapes and non-naturalistic perspective, both typical of Folk Art. Another interesting and exemplary aspect of the work is the detailed representation of the natural environment. The artist has included various types of trees, foliage, and birds, creating a sense of harmony between human society and nature.

The thematic significance of this piece is in its reflection on early American life and values. The grandeur of the mansion suggests wealth and social status, while the surrounding smaller homes and buildings indicate a thriving community and a sense of natural hierarchy. The presence of the ship highlights the importance of trade and transportation during the colonial era.

Oil on wood - Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York

Eliza Jane Fay

Created by Folk artist Ruth Henshaw Bascom in 1840, this portrait shows a girl in a profile view. In formal terms, it is marked by simplicity and elegance. Bascom's preference for soft, rounded shapes is evident in the gentle curves of Eliza Jane's dress, the scalloped edge of her collar, and the outline of her hair elegantly swept behind her ear, adorned with a daisy-like earring. The use of muted colors and the flat representation reflect the naive style typical of Folk art. The attention to detail, particularly in Eliza's facial features and the design of her pendant, indicates the artist's skill in capturing likeness and personal adornment.

In the context of American Folk art, Bascom's work is significant both for its documentation of the lives of women and in indicating the role of women artists within Folk art. The wife of a minister, Bascom initially began drawing as a leisure activity, but began traveling and creating commissioned portraits as her work became known. This portrait stands out within her body of work due to its unique composition, the subject's body depicted in an almost three-quarter view.

Bascom deliberately chose this angle to prominently showcase the subject's locket, inscribed with the poignant words, "In Mem[ory of] Geo. Washingt[on]," a common mourning necklace worn by Victorian-era women and young girls. Portraits like this were often commissioned to commemorate individuals and were treasured family heirlooms, emphasizing the cultural and societal norms of the period, including the importance placed on modesty and propriety.

Pastel and pencil on wove paper - Fenimore Art Museum, New York

Red-breasted Merganser Drake

This drake decoy, created by Captain Charles C. Osgood (1820-86) from Long Island, New York, is crafted from wood and painted to represent the natural appearance of a duck. The use of glass eyes adds a lifelike quality to the decoy, enhancing its realism. Originally devised by Native Americans and later adapted by European settlers, decoys were used to attract wildfowl within range for hunting. By the nineteenth century, the creation of wooden decoys had evolved into a highly realistic art form, often reflecting the individual artistry of the carver.

The broader genre of decoy carving in American Folk Art is characterized by its blend of practicality and artistry. Carvers like Lothrop T. Holmes, and Anthony Elmer Crowell, among others, brought a high level of detail and lifelike quality to their works, making it prized both for its functional use and for its aesthetic appeal. Decoys were often used in rigs, with specific designs tailored to local hunting conditions and bird migratory patterns. Over time, the artistry of decoy carving has been recognized and preserved, with pieces like the Red-breasted Merganser Drake serving as enduring symbols of this folk-art form.

Paint on wood with glass eyes - American Folk Art Museum, New York

American Five-String Banjo

This banjo boasts a finely finished wooden neck and a circular body with a taut, resonant drum-like head (traditionally this would have been made from animal skin). It has five strings, with one shorter string used as a drone (a continually-played note), and is equipped with five brackets. The neck is adorned with frets for precise finger placement, and the tuning pegs allow for easy pitch adjustments of each string. This blend of materials and meticulous design results in the banjo's unique sound, which is both bright and percussive, capturing the quintessential essence of this iconic folk instrument.

The craftsmanship involved in making a banjo, from the selection of materials to the construction techniques, highlights the artisanal skills passed down through generations. This design was commonly retailed through Sears, Roebuck and Co. catalogs, making it an affordable instrument widely accessible to music enthusiasts during the early twentieth century via mass marketing and mail-order services.

The banjo's role in community gatherings, storytelling, and entertainment underscores its importance in the social and cultural life of American folk traditions. Moreover, the significance of the banjo to American popular music cannot be overstated. Originating from African instruments brought to America by enslaved people, the banjo became a cornerstone of various musical genres, including bluegrass, country, and folk. Its development over time reflects the cultural blending that defines American music. The five-string banjo, in particular, is essential to the bluegrass genre, with its rapid picking and rhythmic drive.

Wood, metal, animal skin - National Museum of American History, Washington

Mardi Gras Apron

This Mardi Gras apron from the 1950s showcases intricate craftsmanship, its surface a sea of vibrant glass beads fastened onto velvet, chenille, and buckram. The apron features a stylized representation of a Native American in elaborate traditional dress, the visual flourishes of the outfit emphasized with meticulous beadwork. The use of bold colors reflects the celebratory and vibrant nature of Mardi Gras.

This apron and others like it hold significant cultural value in relation to New Orleans's Mardi Gras culture. Introduced by French settlers in the seventeenth century and firmly established in New Orleans by the mid-eighteenth century, Mardi Gras, or "Fat Tuesday," marks the onset of Lent with parades, parties, costumes, and lively celebrations. Since the nineteenth century, groups known as "krewes" have organized annual Mardi Gras Day parades.

Mardi Gras is of particular significance to African American folk traditions. Historically excluded from white-organized parades, African Americans developed their own celebrations, which evolved into significant cultural events. Often these incorporated Native American symbolism, in solidarity with the subjugated Indigenous American population during the era of slavery.

Glass beads on velvet with chenille and buckram - American Folk Art Museum, New York

Squirrel

Felipe Archuleta (1910-91), an accomplished carpenter from New Mexico, devoted over three decades to his animal carvings. His transformation into a Folk artist began when he started shaping pieces of cottonwood into fantastical animals inspired by children's book and natural history magazines. His carvings are distinguished by their expressive, often whimsical forms. In this case, the squirrel's body is carefully carved to reflect the natural contours and fur patterns of the animal, with a painted surface that adds liveliness to the piece. Often, Archuleta accentuates the wild and fierce aspects of his animal carvings by giving them irregularly shaped teeth, intense, wide-eyed gazes, and exaggerated features such as prominent snouts and genitals.

Archuleta's technique showcases his mastery of carpentry tools. His sculptures, typically assembled with glue or nails, also feature an eclectic mix of materials that he finds himself or obtains from his neighbors. For instance, he might use bottle caps, a comb, rope, or a broom to enhance the details. This use of found materials is typical of the way contemporary Folk art embraces the spirit of bricolage and recycling.

Archuleta's work also embodies a shift in American Folk art from purely functional or naïve objects to pieces celebrated for their artistic merit, created with an awareness of the artistic tradition in which they are placed. His carvings are lauded by both traditional and contemporary collectors, underscoring the broad of Folk art within the mainstream art world.

House paint on cottonwood with rubber and glass - Smithsonian American Art Museum, Washington

Beginnings of American Folk Art

Colonial Period

The term "colonial period" refers to the era of American history when the future United States were under the control of European powers, primarily Great Britain. This period began in the early seventeenth century, when emigrants from various European countries settled in America, bringing with them diverse artistic traditions. These intermingled with Native American and African influences to create an eclectic set of creative traditions that constitute the origins of American Folk Art as we understand it today. This period saw the production of a wide array of functional and decorative objects, including textiles, pottery, furniture, and paintings, often created by self-taught artisans and craftspeople.

During this era, Folk Art was primarily utilitarian, consisting of everyday objects embellished with artistic designs. Quilts, samplers, and weathervanes, for example, often featured intricate patterns and motifs that were both decorative and symbolic. Portrait painting also became popular, with itinerant artists traveling from town to town to capture the likenesses of colonial-era families. These portraits, often characterized by their flat, two-dimensional style and attention to detail, provide a fascinating glimpse into the lives and social customs of early American settlers.

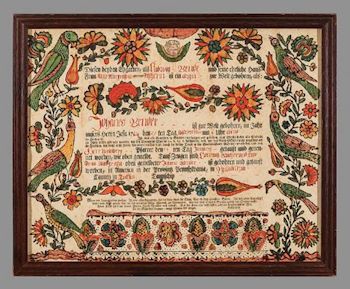

One notable genre of Folk Art to emerge during the colonial period was Fraktur. This was a style of illuminated manuscript created by the Pennsylvania Dutch, immigrants who settled in the eastern US state of Pennsylvania during the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries. Fraktur involves framing gothic script with detailed and colorful patterns featuring flowers, birds, and other pictures and symbols. It is also characterized by elaborate calligraphy.

Fraktur style was often used in the crafting of important documents such as birth and baptism certificates, marriage records, and house blessings. These documents were made with ink and watercolor on paper and were cherished not only for their functional purpose but also for their beauty.

Identity Formation

During the early twentieth century, American Folk Art gained recognition and legitimacy among collectors and art historians, with the first major exhibition held at Museum of Modern Art (MoMA) in New York in 1932. It is around this time that we can first speak of Folk Art as a coherent idea or term, rather than a set of disparate techniques and traditions awaiting critical appraisal. The MoMA exhibition catalog, for example, defined Folk Art as "the expression of the common people, made by them and intended for their use and enjoyment". It was not, the catalog added, "the expression of professional artists made for a small cultured class, and it has little to do with the fashionable art of its period. It does not come out of an academic tradition passed on by schools, but out of craft tradition plus the personal quality of the rare craftsman who is an artist."

Because it was created by ordinary people, Folk Art was often seen as more authentically American than fine art. It was taken to embody the 'true', un-self-conscious character of the nation. The collection and promotion of Folk Art from the early twentieth century onwards thus helped a still-young nation define a sense of identity independent of Europe, an innate 'Americanness'.

During this period, the American public and cultural institutions outside the gallery network also began to recognize the cultural and historical significance of Folk Art. The Federal Art Project, part of the Works Progress Administration (WPA) during the Great Depression, played a crucial role in documenting and preserving Folk Art traditions. This government initiative aimed to support artists and craftspeople working in time-honored styles, helping to ensure that Folk Art was preserved and celebrated as an integral part of American cultural heritage.

The early twentieth century also saw the rise of influential collectors and scholars dedicated to studying and promoting Folk Art. Figures such as Abby Aldrich Rockefeller and Holger Cahill were instrumental in this movement. Rockefeller's extensive collection formed the basis of the folk-art collection at the Williamsburg Folk Art Museum in Virginia, which opened in 1957. Cahill, who directed the Federal Art Project, was pivotal in legitimizing Folk Art within academic and museum contexts.

Urbanization and Industrialization

After the Civil War, mass migration from rural to urban areas and the rise of mechanical production processes diminished the functional value of handmade items. While this resulted in fewer items being produced that might be defined as Folk Art, it also imbued those which remained with a new kind of magic, a sense of connection to a longed-for, pre-industrial past. The catalog for MoMA's 1932 Folk Art exhibition is melancholic in tone when discussing the fading traditions of folk art: "A few of the old craftsmen remained, but ... their creative efforts met no response from a public whose tastes accepted only those produced by machines. By the end of the [nineteenth] century ... American folk art was dead."

This reflected the wider nostalgia for a pre-industrial past that accompanied rapid industrialization and urbanization. Artists and collectors sought out folk-art pieces for their homes, studios, and galleries as icons of a bygone age. But the new academic and cultural interest in folk art also had recent historical precedents.

The Arts and Crafts connection

In particular, the international Arts and Crafts Movement of the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries, beginning in Britain, played an early role in reviving interest in Folk Art. British writers and artists such as William Morris and John Ruskin, though not exactly connoisseurs of Folk Art in the sense explored here, championed handcraftsmanship and traditional techniques. They looked back not to a living folk tradition but to a medievalist notion of collective, artisanal creativity. Like the folk-art revivalists, they also felt that industrialization was dehumanizing creative expression.

The increase in appreciation for Folk Art in North America came some decades after the initial flourishing of the Arts and Crafts movement in Britain. But it can be seen to have followed in its footsteps. The Folk Art movement combined an Arts and Crafts-like emphasis on hand-workmanship, cottage industry, and anti-mechanical sentiment, with a more pronounced interest in 'naïve' or 'unsophisticated' forms. A direct thread can also be traced between the workshops and colleges of the Arts and Crafts age and the preservation of traditional techniques through education which was a key expression of the Folk Art movement.

Modernist Influences

The early twentieth century saw a growing interest in Folk Art among academics and artists seeking to break away from intellectual and stylistic conventions and explore new forms of expression. As classical idealism and realism were abandoned during the era of Cubism and other key modernist art movement, the art world began to appreciate the untrained styles of Folk artists, which might previously have been seen as 'primitive'.

When Surrealism emerged as a response to the perceived over-rationalism of Cubism, Surrealists such as Andre Bretón and Max Ernst found inspiration in the spontaneity and uninhibited creativity of Folk Art. If the earliest twentieth-century modernists - such as the Cubists - had been interested in how Folk Art could suggest new approaches to design, or to the use of form and perspective, the Surrealists were more interested in Folk Art as a way of tapping into a raw creative spirit. This reflected their interest in the unconscious mind as the source of true creativity.

For many modern artists, from Picasso to Breton, an interest in Folk Art went hand in hand with an interest in non-Western art. Many artists built up collections of African, Oceanic, and other non-European art, taking the unfamiliar approaches to form and perspective they found in this work as creative inspiration. (Today, this is generally perceived as problematic in its closeness to a form of imperial plunder.)

The Art Brut movement of the post-1945 years, spearheaded by the French artist Jean Dubuffet and others, led to a second great wave of interest in Folk Art. Art Brut foregrounded the unrestrained creative impulses of children, individuals with mental illnesses, and other 'untutored' artists. This provided a new framework in which the instinctive creativity of Folk Art could be celebrated. These traditions live on in the celebration of artists from socially marginalized backgrounds and perspectives as 'outsider artists' (a term sometimes used interchangeably with 'Folk artist').

Preservation and Revival

Beginning in the early twentieth century, collectors and scholars recognized the importance of preserving Folk Art as a unique facet of American identity amidst the increasing effects of cultural homogenization due to global consumer capitalism and advertising culture. Institutions like the Museum of Modern Art (MoMA) in New York and the American Folk Art Museum played crucial roles in championing folk art through exhibitions and scholarly research.

During the Great Depression of the 1930s, the Works Progress Administration (WPA) under President Franklin D. Roosevelt's New Deal further bolstered the preservation efforts by supporting Folk artists through federal funding. This period witnessed the documentation and revitalization of traditional crafts and artistic techniques across rural America, ensuring their continuity and relevance in a changing society. Artists such as Grant Wood, known for his iconic painting American Gothic (1930), drew upon Folk art motifs and rural imagery, contributing to a broader cultural appreciation for these forms.

Beyond the halls of museums and galleries, grassroots endeavors led by artisans and communities have been pivotal in revitalizing traditional crafts like quilting, pottery, and woodworking. Organizations such as the American Craft Council, the Woodworkers Guild of America, and Seagrove: the Pottery Capital of the United States actively support artisans in preserving these crafts by providing resources, workshops, and opportunities for collaboration. These efforts not only preserve historical techniques but also transmit invaluable skills to future generations.

Concepts and Styles

African American Folk Art

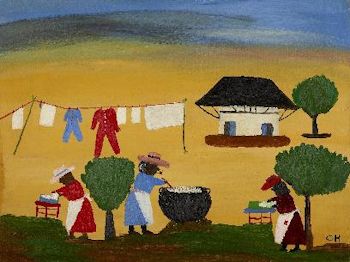

African American Folk Art emerges in part from the rich creative cultures that enslaved people brought with them from Africa to North America. It is equally shaped by the modern cultural legacies of slavery, segregation, and the fight for civil rights. This style of Folk Art spans diverse forms such as quilting, sculpture, painting, and music. It is often narrative in nature, reflecting on themes such as resilience, identity, and the pursuit of social justice.

African American Folk Art is deeply infused with spirituality and religion, integrating African spiritual practices alongside Christian iconography. For instance, artists might use Kongo cosmograms, depicting the cyclical nature of life, death, and rebirth through the motif of a cross within a circle. Or, in its performed aspect, African American Folk Art might include elements of Yoruba ritual, honoring ancestors and deities through offerings, drumming, dancing, and prayer. This kind of ritual might be used to maintain harmony between the sacred and corporeal realms. Christian motifs of salvation and redemption often manifest in African American folk-art too, blended with an African heritage to create new, syncretic forms.

Clementine Hunter (1886/87-1988) is an example of a renowned African American Folk artist, celebrated for her vivid depictions of plantation life. A self-taught artist, Hunter created over 5,000 paintings that capture the daily lives, traditions, and spiritual practices of African American communities in the rural South. Her work embodies many of the common characteristics of African American Folk Art, including bold colors, elemental compositions, and a strong narrative quality often featuring scenes of cotton-picking, baptisms, and other communal activities.

Caribbean American Folk Art

Caribbean American Folk Art is rooted in the diverse heritage of Caribbean immigrants and their descendants in the United States. It amalgamates the African, Indigenous, European, and Asian influences that shape Caribbean identity. Caribbean American Folk Art is often infused with spiritual symbolism and draws from social storytelling traditions. Artists might draw inspiration from folklore, mythology, and everyday life. If working in three dimensions, they used materials ranging from natural fibers and clay to recycled objects, reflecting resourcefulness and environmental consciousness. Caribbean American Folk Art serves as a means of preserving collective heritage while also fostering cohesion and shared identity amongst the Caribbean diaspora in the USA.

A notable Caribbean American Folk Art-form is Junkanoo costumes, blending African and Caribbean aesthetics with modern design to celebrate cultural traditions and community identity. Originating from the Bahamas and other Caribbean islands, Junkanoo costumes are known for their elaborate designs, bright colors, and use of materials such as feathers, shells, and papier-mâché. These costumes are central to the Junkanoo parades held on Boxing Day and New Year's Day, celebrated in the Bahamas and in several locations in the United States, particularly in Miami and Key West, Florida. Participants dance to the beat of goatskin drums and cowbells, showcasing a powerful expression of cultural pride.

Native American Folk Art

Native American Folk Art includes motifs reflecting on tribal histories, common beliefs, and daily life. Forms and media include pottery, basketry, beadwork, and textiles. This kind of Folk Art can serve as a cultural continuum, maintaining and revitalizing Indigenous identities amid historical and contemporary challenges, including the subjugation and marginalization of Indigenous American communities by European immigrants. It can also fulfill ceremonial roles, marking rites of passage, seasonal cycles, and spiritual practices.

One prominent example of Indigenous American art is Navajo rug weaving. Traditionally handwoven on upright looms, Navajo rugs are celebrated for their intricate geometric patterns and vibrant colors. They often incorporate symbolic references to spiritual beliefs as well as responding to the natural landscapes and climate of the Southwest USA. For example, the use of diamond shapes might represent the four sacred mountains of the Navajo religion. The inclusion of zigzag lines might symbolize lightning, and therefore spiritual transformation. Each motif and color choice in Navajo rugs is deliberate, conveying concepts of harmony, balance, and connection to the land.

Textiles

Textile works are integral to American Folk Art, blending practical utility with artistic expression. Quilting, for instance, serves as a powerful narrative medium, whereby fabric scraps are integrated into designs that reflect community, memory, and personal identity. Folk-art quilts often feature geometric patterns, appliqué techniques (patches of fabric attached to larger background patches to create picture or designs), and vibrant colors, imbuing each stitch with a sense of place and belonging.

The introduction of European textile arts to the Americas profoundly influenced various ethnic groups, including Native Americans and African Americans, who incorporated new materials and techniques into their traditional arts. In the Southwest, Indigenous communities borrowed the use of sheep's wool from early Spanish settlers, developing distinctive styles of rug, blanket, and clothing. The use of wool was taken up by other Native American groups, too, with the Navajo and others preserving ancient sheep breeds that had vanished in Europe, thus enhancing the cultural significance and value of the works created.

Beyond their cultural heritage, textile-based Folk Arts can play a therapeutic role. For example, during the 1920s, knitting was taught to wounded World War One veterans. Many contemporary artists draw inspiration from textile-based Folk Arts, using traditional techniques to explore themes such as familial heritage, domestic labor, feminism, and kitsch, bridging historical traditions with modern artistic approaches.

Pottery

From the utilitarian pieces crafted by colonial-era potters to tradition-blending work by contemporary artists, folk pottery has evolved over time while retaining a distinctive charm. Early American settlers relied on local clays to fashion everyday items such as cooking vessels and storage jars, often embellishing them with rudimentary designs. As industrialization spread, traditional pottery techniques persisted in rural areas, where artisans continued to create objects embodying local styles and cultural values. The formalization of interest in Folk Art during the early twentieth century elevated this kind of work into a revered element of American cultural heritage. Potters such as the Lanier Meaders family of Georgia, for example, gained renown for their unusual designs and decorative glazes.

Several regions have distinguished themselves in the realm of folk pottery. In the Appalachian Mountains of North Carolina and Georgia, pottery traditions thrive, with a focus on utilitarian forms adorned with folk-inspired designs. In the Southwest, particularly in New Mexico and Arizona, Native American pottery embodies centuries-old techniques often infused with contemporary aesthetics. In the Northeast, Pennsylvania Dutch communities and studios in New York's Hudson Valley also contribute to the narrative, with many potters in this area using slipware techniques.

Today, American folk pottery is enjoying a resurgence of interest and is celebrated for its authenticity and connection to indigenous heritage. Modern folk potters draw inspiration from historical techniques while incorporating contemporary influences, resulting in a diverse range of styles that span from traditional to avant-garde. Collectors and enthusiasts value folk pottery not only for its aesthetic appeal but also for its role in preserving cultural narratives and regional identities.

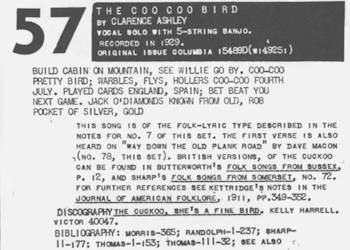

Music and Instruments

Throughout American history, folk music has served as a vehicle for storytelling and social commentary. Instruments from Europe, Africa, and Indigenous regions, such as the banjo, fiddle, and guitar, all became integral to American folk music, their use adapted over time in different regions to reflect local styles and rhythms. In rural areas, music gatherings and folk festivals provided platforms for musicians to preserve and innovate upon traditional tunes, fostering a sense of communal identity and continuity across generations.

Artist Harry Everett Smith made a seminal contribution to American folk music with his groundbreaking Anthology of American Folk Music (1952). This collection, compiled from Smith's extensive personal collection of old 78rpm records, meticulously curated and documented a wide array of traditional folk, blues, and country recordings from the early twentieth century.

Smith's anthology not only revived interest in obscure recordings but also played a pivotal role in shaping the American folk revival of the 1950s-60s. Artists such as Bob Dylan, Joan Baez, and Pete Seeger cited the anthology as a major influence, inspiring them to explore and reinterpret traditional folk songs. Smith's anthology continues to be celebrated as a cornerstone in the preservation and appreciation of American folk heritage.

Later Developments - After American Folk Art

Since the turn of the millennium, American Folk Art has experienced a renaissance, driven by a renewed interest in handmade, artisanal practices amidst a burgeoning digital economy that connects artists with wider audiences. The early 2000s saw a resurgence in traditional crafts, fueled by the Maker Movement, which emphasized DIY culture and the value of crafting handmade objects. This period also witnessed the rise of platforms such as Etsy, where Folk artists could sell their work directly to consumers, bypassing traditional galleries and making Folk art more accessible and diverse.

In recent years, American Folk Art has also become a significant medium for social and political commentary. Artists have used folk traditions to address contemporary issues such as immigration, racial inequality, and environmental concerns. This modern iteration of Folk Art often incorporates recycled materials and found objects, reflecting both a commitment to sustainability and a commentary on consumer culture. Exhibitions and festivals celebrating Folk Art have proliferated, providing platforms for artists to showcase their work and engage with communities.

Recent years have also seen a revival and consolidation of interest in Folk Artists of older generations. For example, the early-twentieth-century paintings of Grandma Moses have been celebrated for their spirited representation of rural American farming life. So too has the visionary savant Leonard Knight, who created huge installation works such as Salvation Mountain. The colonial-era portrait painter John Brewster Jr. has also been the subject of revisionist interest and rediscovery, his work appreciated for its flat, stylized, proto-modernist qualities.

Meanwhile, American Folk Art continues to be marked by inclusivity and representation. New generations of Indigenous artists, African American artists, and immigrant communities, for example, have brought new perspectives and traditions to the Folk Art landscape. As a result, American Folk Art today is a dynamic and evolving field, reflecting the country's multifaceted cultural identity.

Useful Resources on American Folk Art

- The Flowering of American Folk Art (1776 - 1876)By Jean Lipman and Alice Winchester

- Discovering American Folk ArtOur PickBy Cynthia V. A. Schaffner

- American Folk PaintingBy Mary Black

- A Kind of Archeology: Collecting American Folk Art, 1876-1976Our PickBy Elizabeth Stillinger

- A Shared Legacy: Folk Art in AmericaBy Richard Miller, Avis Berman, et al.

- American Anthem: Masterworks from the American Folk Art MuseumBy Stacy C. Hollander and Brook Davis Anderson

- American Folk Art of the Twentieth CenturyBy Jay Johnson, William C. Ketchum Jr., et al.

- Contemporary American Folk Art: A Collector's GuideBy Chuck Rosenak and Jan Rosenak

- Harry Smith's Anthology of American Folk Music: America Changed Through MusicBy Ross Hair, Thomas Ruys Smith

Ask The Art Story AI

Ask The Art Story AI