Summary of Ancient Egyptian Art

Ancient Egyptian art has had an incalculable impact on the creative spirit of all subsequent civilizations across Europe and the Mediterranean, including our own. The sophisticated culture that flourished along the Nile from 3,000 BC onwards is the origin of so much that we now taken for granted as an aspect of human creativity: the realistic representation of the body in sculptural form; long-lasting public architecture; formalized visual representations of nature, and so on. But, in spite of this connection to the present, the art of Ancient Egypt also can also appear amazingly strange and alien. It is the product of a culture steeped in religion and a sense of connection to the afterlife, in which art served precise ritual purposes that must be understood to truly engage with the creative riches it produced.

Key Ideas & Accomplishments

- Much Ancient Egyptian art served a ceremonial purpose connected to the gods and afterlife. It would have been left in tombs or used to decorate the interiors or facades of mortuaries. Art like this was meant to glorify the deceased by showing the great deeds they had accomplished in life, but it also provided their eternal soul (or ka) a dwelling place and sources of pleasure in eternity.

- Ancient Egyptian sculpture is characterized by an amazing stillness and formality. Human figures often appear to emerge from solid blocks of rock, retaining the straight lines and rigid uprightness of the underlying shapes. This is connected to the role of sculpture in Ancient Egypt to convey the essential, eternal qualities of an individual rather than a fleeting impression of them.

- The formality of Ancient Egyptian art is often contrasted with the naturalism of the Ancient Greek style, which had a large impact on subsequent European art. Without the Egyptian tradition to define itself against, however, Greek painting and sculpture would not have emerged in the way it did. Moreover, the key features of Ancient Egyptian architecture, such as the use of columned porticos and grand rectangular forms, had a profound influence on the whole Greco-Roman period.

Overview of Ancient Egyptian Art

Ancient Egyptian art is known for its beauty, somberness, and technical brilliance. Although it influenced the whole of subsequent Western art, it can appear strange and alien to us because of the highly religious and hierarchical society it came from.

Artworks and Artists of Ancient Egyptian Art

Palette of King Narmer

This cosmetic palette is one of the earliest widely known works of Ancient Egyptian art, As Fred Kleiner explains, "Narmer's palette is an elaborate version of a utilitarian object commonly used...to prepare eye makeup, which Egyptian men and women used to protect their eyes against irritation and the glare of the sun as well as to enhance their appearance."

In terms of form and appearance, this is a sophisticated and detailed piece of craft. The palette is carved is carved all over with intricate narrative reliefs, including illustrations of two cows on each side to represent the form of the goddess Hathor. On the back side of the palette, King Narmer is the largest figure (to signify his status, as is common in the art of many early civilizations), and is shown killing an enemy. Other foes lie vanquished below him. Narmer's servant, a foot washer, carries his sandals. The King also appears a second time, as the god Horus in falcon form, indicating the belief that Egyptian gods could take on both human and animal forms. On the front side, key images include two cats with elongated, entwined necks framing the recess in the palette where pigment could be mixed. Narmer is depicted for a third time on the topmost register, reviewing the bodies of his slain enemies, while the hieroglyphics at the top of both sides of the palette indicate Narmer by name.

Of the importance of this work, Kleiner states: "the palette is important not only as a document marking the transition from the prehistoric to the historical period in ancient Egypt but also as one of the earliest examples of the formula for figure representation that characterized most Egyptian art for 3,000 years." This work is rich in symbolism and provides an important example of Ancient Egyptian use of art as a means of enforcing legitimacy of rule, elevating the gods, and recording historical events. This could be achieved through subtle, symbolic means. For example, the intertwined feline forms have been taken to represent the unification of Upper and Lower Egypt, an act credited to King Narmer.

The palette is also notable in indicating that a formalized written language was in use in Early Dynastic Egypt, a sign of significant development. According to Jaromir Malek, "the scenes are complemented by rudimentary hieroglyphic inscriptions which convey the name of the king [and others including] the royal sandal-bearer. They also record the name or ethnicity of the foreigner being slain by the king, identify the rectangle behind the king on the recto as the royal palace, indicate 6,000 as the number of prisoners held captive by the god Horus....These are among the earliest known hieroglyphic inscriptions and such labelling remained the chief use of the hieroglyphic script throughout the Early Dynastic Period and the early Old Kingdom."

Slate - Egyptian Museum, Cairo

Imhotep, Stepped Pyramid of Djoser

This structure is one of the earliest examples of the pyramid form so iconic within Ancient Egyptian art and architecture. While later pyramids are smooth and sleek, the earliest examples are stepped, consisting of several rectangular, mastaba-like structures, decreasing in width, stacked on top of each other. According to Fred Kleiner, "Djoser's pyramid is one of the oldest stone structures in Egypt and the first stone pyramid. Begun as a large mastaba with each of its faces oriented toward one of the cardinal points of the compass, the tomb was enlarged at least twice before assuming its ultimate shape. About 200 feet high in its final form, Djoser's stepped pyramid is the first truly grandiose Egyptian tomb."

Besides being one of the first surviving pyramids, this work is important for several other reasons. Firstly, it provides concrete proof of the importance Ancient Egyptians placed on the afterlife and how art and architecture aided the quest for a successful eternity. It also remained behind as a symbol of the ruler's earthly power after they were gone. As Kleiner states, "Djoser's pyramid is a tomb...and its dual function was to protect the mummified king and his possessions and to symbolize, by its gigantic presence, his absolute and godlike power. Beneath Djoser's pyramid was a network of several hundred underground rooms and galleries cut out of the Saqqara bedrock. The vast subterranean complex resembles a palace. It was to be the king's home in the afterlife." Tombs were not simply resting places but eternal homes, and they needed to be designed accordingly.

This work is also unique in that we know who the architect was, a courtier named Imhotep. He was a highly valued member of King Djoser's inner circle and, as Kleiner states, his "is the first recorded name of an artist anywhere in the world. A man of legendary talent, Imhotep also served as Djoser's official seal bearer and as high priest of the sun god Re. After his death, the Egyptians deified Imhotep as the son of the god Ptah."

Stone - Saqqara, Egypt

Great Sphinx (with the pyramid of Khafre in the background)

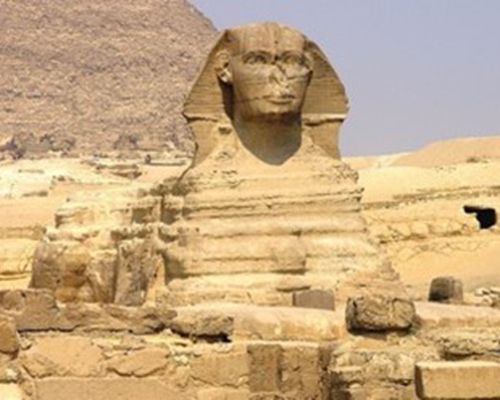

This large-scale sculpture, 65 feet in height, was a monumental creation of Old Kingdom Egypt. The sphinx is a composite creature, with the body of a lion and head of a human.

Rich in symbolism, this work reflects the Ancient Egyptian belief that gods and kings in their divine aspect could take these hybrid, human-and-animal form. In this case, the likeness may be that of King Khafre, which would make sense considering it sits in front of the king's pyramid. Kleiner notes that "the sphinx - a lion with a human head - was an appropriate image for a king. The composite form suggests that the Egyptian king combined human intelligence with the fearsome strength and authority of the king of beasts." In this way the sphinx would serve as a powerful visual reminder to every Egyptian of the king's strength and divine right to rule. It was also something for the king to revel in, as both the sculpture and his pyramid were built well in advance of his death.

The Great Sphinx has served as a backdrop to major historical events. For example, Napoleon's Battle of the Pyramids (1798) took place nearby; it was wrongly believed to have resulted in the sphinx's nose being blown off by a cannonball. The modern Egyptian state has issued banknotes with the sphinx on, and it has become a major symbol of national pride. The sculpture continues to serve as one of the most iconic reminders of the stunning engineering prowess of an ancient state.

Sandstone - Gizeh, Egypt

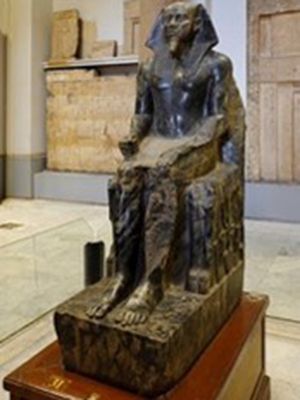

Khafre enthroned

This statue depicts one of the key rulers of the Old Kingdom, King Khafre. Rigid and formally posed, he is seated wearing a kilt, staring straight ahead, his arms folded at 90 degrees and resting on his thighs. As Kleiner notes, the ruler sits "on a throne formed of two stylized lions' bodies. Intertwined lotus and papyrus plants - symbolic of the united Egypt - appear between the throne's legs. Khafre has the royal false beard fastened to his chin and wears the royal linen headdress. The headdress covers his forehead and falls in pleated folds over his shoulders. Behind Khafre's head is the falcon that identifies the king as the 'Living Horus'."

Ancient Egyptian rulers were always depicted seated or standing, their appearance rigidly formal in either case, their dress and accoutrements full of symbolism, as Kleiner explains. "As befitting a divine rule, the sculptor portrayed Khafre with a well-developed, flawless body and a perfect face, regardless of his real age and appearance. Khafre's portrait is not a true likeness and was not intended to be. The purpose of Egyptian royal portraiture was not to reproduce the distinctive shapes of bodies or to record individual features, as was the case, for example, in Republican Rome. Old Kingdom sculptures sought to create idealized images that communicated the divine nature of Egyptian kingship." Khafre's divinity is also confirmed through a symbolic association with the gods. In this case, the falcon Horus wraps his wings around Khafre's head.

The anchoring of art in religion in Ancient Egypt was fundamental to each work that was created. It was believed that the deceased's ka or eternal spirit could return if the ka had a place to rest and so sculptures were created and left in tombs to serve as repositories. According to Kleiner, while the bodies were always perfect in form and features, "each king's portraits incorporated enough distinctive facial traits to enable his ka to know where to reside."

Diorite - Egyptian Museum, Cairo, Egypt

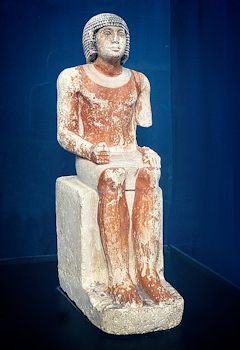

Seated Scribe

Not all sculptures created during the Old Kingdom period were of kings and gods. High-ranking or important figures in the king's inner cycle might also be considered a fit subject for statuary, as this stunningly naturalistic work show. The figure of a scribe is carved from limestone, seated cross-legged, holding a scroll to indicate his job and social status.

A work like this makes a striking contrast with the formal block sculptures of standing or seated monarchs. The scribe has a far looser posture, and is shown in a more frail, earthly frame, the natural curves and droops of the torso foregoing the perfection evident in the royal body. This reflects the subject's less rarefied social position, as Kleiner notes: "The scribe sits directly on the ground, not on a throne or even on a chair. Although he occupied a position of honor in a largely illiterate society and performed a variety of official duties, the scribe was not as exalted a figure in Egyptian hierarchy as the king, whose divinity made him superhuman. Consequently, his portrait is not idealized. Quite the contrary. For example, the sculptor reproduced the scribe's sagging chest muscles and protruding belly. These signs of age would have been disrespectful and wholly inappropriate in a depiction of an Egyptian god-king or members of his family."

Ironically, the naturalism of the work allows us to form a clearer mental picture of the subject than with the grand visages of monarchs. As Kleiner notes, "the sculptor conveyed the personality of a sharply intelligent and alert individual", which carries down to us through millennia. At the same time, the individual represented here was far from a typical ancient Egyptian, his portly frame indicating a rare degree of wealth and physical comfort. A full stomach would have been a rarity for most subjects of ancient Egypt.

Painted limestone - Musée du Louvre, Paris, France

Menkaure and Khamerernebty

The Old Kingdom ruler Menkaure here appears next to a female companion who is likely to be his wife Khamerernebty, though some hold it to be the goddess Hathor. The work highlights the block-like aspect of Old Kingdom statuary, figures seeming to emerge from a rectangular block of stone. As Kleiner notes, "Menkaure's pose - duplicated in countless other Egyptian statues - is rigidly frontal with the arms hanging straight down and close to his well-built body. He clenches his hands into fists with the thumbs forward and advances his left leg slightly." The perfect physical forms of the figures were intended to convey their monarchical status.

This work indicates the political alliance between king and queen through their physical connection, indicating the limited extent to which women were allowed to achieve high social status in Ancient Egypt. But no shift occurs in the angle of the hips to correspond to the uneven distribution of weight. Kleiner points out that Khamerenebty...stands in a similar position [to the king]. Her right arm, however, circles the king's waist and her left hand gently rests on his left arm. This frozen stereotypical gesture indicates their marital status or, if king and goddess, their shared divinity. The two figures show no other sign of affection or emotion and look not at each other but out into space."

While the arrangement of the two bodies might seem to indicate a lack of emotional connection, this reflections the function of the artwork rather than the details of the human relationship. As Kleiner explains, "the artist's aim was not to portray vibrant living figures but to suggest the timeless nature of the stone statue that might need to serve as an eternal substitute home for the ka."

Graywacke - Museum of Fine Arts, Boston, Massachusetts

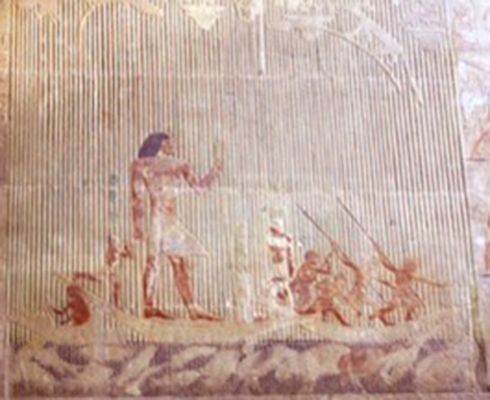

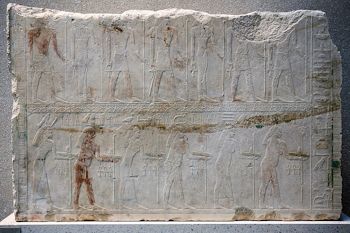

Ti watching a hippopotamus hunt

Carved and painted reliefs were often found in Ancient Egyptian funerary mastaba tombs. This relief is from the tomb of a man named Ti, a high ranking official during the Fifth Dynasty. He is depicted overseeing a hippopotamus hunt.

This work is a particularly good example of how the narrative elements of art in funerary tombs were intended to exalt the deceased individual and entertain their ka or soul. As Kleiner notes, "depictions of the deceased at his funerary meal and scenes of agriculture and hunting fill Ti's tomb. The Egyptians associated farming and hunting as well as dining with providing nourishment for the ka in the hereafter." The activities depicted also "powerful symbolic overtones. In ancient Egypt, success in the hunt, for example, was a metaphor for triumph over the forces of evil." The large size of Ti compared to other individuals depicted, meanwhile, indicates the hierarchy of subjects: "the artist exaggerated the size of Ti to announce his rank."

Kleiner also notes that the "combined frontal and profile views of Ti's body...show its most characteristic parts clearly. This...emphasizes the essential nature of the deceased, not his accidental appearance." The idea here was to convey that which would remain of the subject's soul and body after death. Thus "Ti's conventional pose contrasts with the realistically rendered activities of his tiny servants and with the naturalistically carved and painted birds and animals among the papyrus buds. Ti's immobility suggests that he is not an actor in the hunt. He does not do anything. He simply is, a figure apart from time and an impassive observer of life, like his ka."

Painted limestone - Mastaba of Ti, Saqqara, Egypt

Hippopotamus

While the best-known art from Ancient Egypt is large in size and grandiose in cultural significance, some of the most delightful sculptures that remain from the period were diminutive in size and humble in significance. This beautiful statue of a hippopotamus measures less than five inches high. It is glazed in turquoise blue faience (a quartz-based glaze) and painted with images of plant blossoms native to the Nile.

Many small works like this were created during the later years of the Middle Kingdom, in part to fill the tombs of ordinary Egyptians who could afford neither the costs of commissioning larger sculptures nor the tomb-space to store them. The choice of subject-matter remained symbolically significant, however. According to the Metropolitan Museum of Art, "the seemingly benign appearance that this figurine presents is deceptive. To the ancient Egyptians, the hippopotamus was one of the most dangerous animals in their world. The huge creatures were a hazard for small fishing boats and other rivercraft. The beast might also be encountered on the waterways in the journey to the afterlife. As such, the hippopotamus was a force of nature that needed to be propitiated and controlled, both in this life and the next."

Interestingly, this particular statue has taken on a life in popular culture as well. The statuette has become somewhat of a symbol for the Metropolitan Museum of Art itself. According to the museum's website, "the hippo's modern nickname first appeared in 1931 in a story that was published in the British humor magazine Punch. It reports about a family that consults a color print of the Met's hippo - which it calls "William" - as an oracle. The Met republished the story the same year in the Museum's Bulletin, and the name William caught on!"

Faience - Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, New York

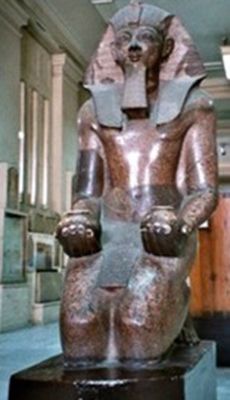

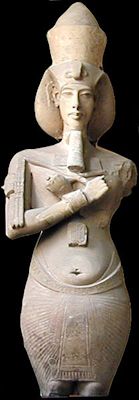

Hatshepsut with offering jars

The female pharaoh Hatshepsut was first the queen of Thutmose II before his death, upon which she ultimately declared herself pharaoh. When she became ruler of Ancient Egypt, she set about building a mortuary temple where her ka could reside for eternity after her death. In addition to the grandeur and elaborate architectural structure of the temple, she filled it with life-size statues of herself. This work is one example. Hatshepsut's devotion to the gods is indicated by the two offering jars she holds, one in each hand. According to the Metropolitan Museum of Art, "the inscription on this statue indicates that Hatshepsut is offering Amun Maat (translated as order, truth, or justice). By making this offering, Hatshepsut affirms that Maat is the guiding principal of her reign."

Strikingly, the female ruler also depicted herself as physically and symbolically male. As Kleiner explains, "her surviving portraits are of two types. In those carved before she consolidated power, Hatshepsut appears as a woman with delicate features, a slender frame, and breasts. In her latest portraits...Hatshepsut uniformly wears the costume of the male pharaohs, with royal headdress and kilt, and in some cases even a false ceremonial beard." Both these features can be seen in this sculpture, making it typical of this later period of consolidatory visual propaganda.

This was part of a wider campaign to present the woman ruler as able to hold power in spite of her gender. This is a trope that we find repeated throughout post-classical history, as, for example in the use of art to reinforce divine power during the reign of Elizabeth I of England. Inscriptions from Hatshepsut's reign refer to her as 'His Majesty.'" Her need to depict herself as a male ruler is a strong visual indication of the fragile control she had to maintain as a female ruler.

Red granite - Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, New York

Senenmut with Princess Nefrura

One of the finest examples of statuary from the New Kingdom period, this block sculpture shows a man with a young girl on his lap, enveloped in his cloak. As Kleiner notes, "the streamlined design concentrates attention on the heads. The sculptor treated the two bodies as a single cubic block with smoothly rounded corners." As was typical of such sculptures, the large flat base is covered with hieroglyphics, anchoring the work in linguistic symbolism.

Whilst pharaohs and gods were the most common subjects of Ancient Egyptian sculpture, other subjects included figures in the inner circles of the monarchs. This piece, for example, features a man named Senenmut who served as chancellor to Queen Hatshepsut. The child he holds is the Queen's daughter, the child's father the Pharaoh Thutmose II. The fact that a non-royal would have such access to the princess visually asserts his power, and shows the role that art played as propaganda in Ancient Egypt even for figures outside the royal line.

According to Kleiner, Senenmut might also have been the queen's lover, indicating further symbolic significance to the work, and to the intimate access its subject was allowed to Hatshepsut's family. As Kleiner notes, "the work is one of many surviving statues depicting Senenmut with the princess, which enhanced the chancellor's stature through his association with the pharaoh's daughter (he was her tutor) and, by implication, with Hatshepsut herself."

Granite - Ägyptisches Museum, Berlin, Germany

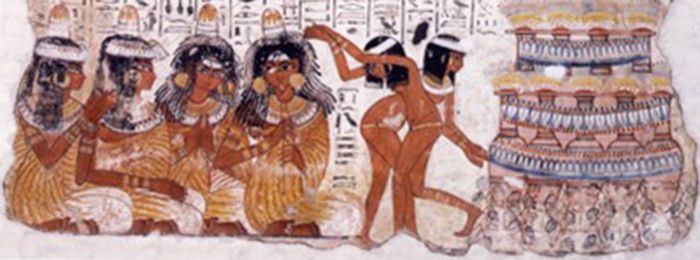

Musicians and dancers, detail of a mural from the tomb of Nebamun

Tomb painting was an important form of artmaking in Ancient Egypt. The Egyptians used a style of wall painting known as fresco secco. According to Kleiner, "fresco secco involves painting on dried lime plaster....Although the finished product visually approximates buon fresco [painting on wet walls], the plaster wall does not absorb the pigments, which simply adhere to the surface, so fresco secco is not as permanent as buon fresco." This accounts for the decay of many such images over the centuries.

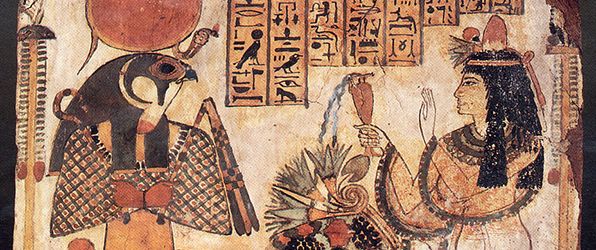

However, several examples of fresco secco painting from Ancient Egypt survive today, including this section from the mortuary fresco of a New Kingdom man named Nebamun. According to Kleiner, "Nebamun, whose official titles were 'scribe and counter of grain,' was a wealthy man who could afford to hire highly skilled painters to decorate his tomb." This panel shows "noblewomen watching and apparently participating in a musical performance in which two nimble and almost nude girls dance in front of the guests at a commemorative funerary ceremony. At these banquets, the guests consumed great quantities of wine and beer to enable them, in their drunken state, to commune with the dead. (The painter took care to include the ample supply of wine jars at the right.)." The ka or soul of the deceased would have been pleased to see such wild celebrations in his honor. This indicates how mortuary art was intended to please the dead, and the key role it played in Ancient Egyptian religious customs.

This work also reflects advances in figurative representation during the New Kingdom period. As Kleiner explains, "the fresco [shows] that New Kingdom artists did not always adhere to the old norms for figurative representation. Nebamun's painter recorded the dancers' overlapping figures, their facing in opposite directions, and their rather complicated gyrations, producing a pleasing intertwined motif at the same time. The profile view of the dancers is consistent with their lower stature in the Egyptian hierarchy. The New Kingdom artist reserved the composite view for Nebamun and his family." It was these complexities of figurative representation that laid the foundations for the sculptural works of the Ancient Greeks centuries later.

Fresco secco - British Museum, London, England

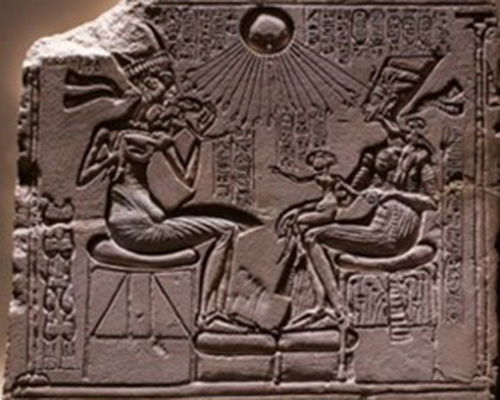

Akhenaton and Nefertiti with three daughters

Carved reliefs made to decorate the tombs and shrines of royals were popular during the New Kingdom period. This work features one of the most unique and influential pharaohs of the period, Akhenaton. He is holding one of his daughters and is seated across from his wife Nefertiti, who holds their other two daughters.

This relief shows the important role art could play in depicting the lives of the pharaohs, as well as their divinity and power. Family was valued almost as much as the gods by ancient Egyptian rulers, and in rare instances this was expressed through visual representation in ways that feel intimate and almost contemporary. Fred Kleiner notes that the "mood" of this piece is "informal and anecdotal. Akhenaton lifts one of his daughters in order to kiss her. Another daughter sits on Nefertiti's lap and gestures toward her father, while the youngest daughter reaches out to touch a pendant on her mother's crown. This kind of intimate portrayal of the pharaoh and his family is unprecedented in Egyptian art, but it typifies the radical upheaval in art that accompanied Akhenaton's religious revolution."

As Kleiner suggests, Akhenaton's rule was highly unusual because of his introduction of an early form of monotheism based on worship of a sun disk called Aton. In the portrait, the family are not just enjoying a loving home life but also "bask[ing] in the rays of Aton, the sun disk, which end in hands holding the ankh, the sign of life." As Kleiner also notes, the religious revolution accompanied an aesthetic one, with sensual and curvaceous lines and forms finding a place in the art of this era, in sharp contrast to the rigidity and formalism of previous Egyptian arms, torsos, and thighs of the seated family, which echo the curving lines of the sun disk.

Limestone - Ägyptisches Museum, Berlin, Germany

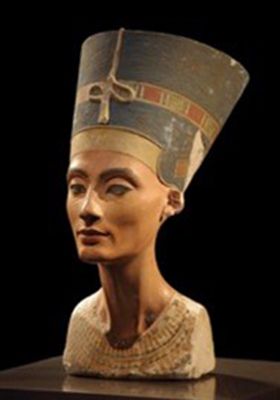

Thutmose, Bust of Nefertiti

Pharaohs and their families were a primary theme of Ancient Egyptian art. One of the most beautiful examples of this is the famous bust of Queen Nefertiti, wife of Akhenaton, held at the Egyptian Museum in Berlin. Remarkably well-preserved decorative elements add to the beauty of the piece, the limestone finished with a painted façade representing the queen bejeweled necklace and crown.

This work highlights the unique artistic style that emerged during the reign of Pharaoh Akhenaton. According to Kleiner, "the portrait exhibits an expression of entranced musing and an almost mannered sensitivity and delicacy of curving contour....With this elegant bust Thutmose [the artist] may have been alluding to a heavy flower on its slender stalk by exaggerating the weight of the crowned head and the length of the almost serpentine neck. The sculptor seems to have adjusted the likeness of his subject to meet the era's standard of spiritual beauty."

The sculptor of this work, Thutmose, is a rare example of an artist known by name from the ancient world. The sculptor's ruined house and workshop were discovered during a German archeological dig in 1912, and were found to contain a horse blinker (eye-guard) inscribed with the sculptor's name and job title. Various works including this bust were discovered in the storeroom of the complex during the same excavation. This gives us a remarkably intimate sense of the life of an ancient artist, whereas normally we would only expect the experiences and actions of the wealthiest and most powerful to be preserved through the centuries.

Painted limestone - Ägyptisches Museum, Berlin, Germany

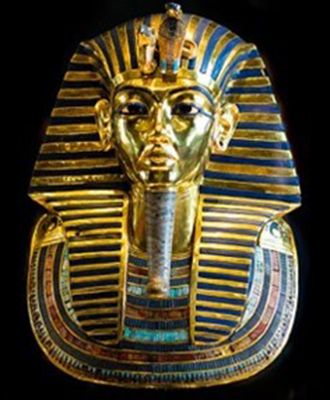

Death Mask of Tutankhamen

This mask, created to cover the body of the young Pharaoh Tutankhamen, is perhaps the most famous of all Ancient Egyptian works of art. It is highly elaborate, made of gold and inlayed rows of stones in shades of blue and red. The Egyptian Museum, Cairo, describes the mask as "an example of the highest artistic and technical achievements of the ancient Egyptians in the New Kingdom." The physical perfection of the figure is not merely for aesthetic reasons: "the exact portrayal of the king's facial features achieved here made it possible for his soul to recognize him and return his mummified body, thus ensuring his resurrection."

The work therefore indicates the importance of art in relation to religious belief in Ancient Egypt, particularly in preparing the subject for the afterlife and reflecting their achievements on earth. All this is indicated by several symbolic features of the mask. "Covering the head of the wrapped mummy in its coffin and activated by a magical spell...the mask ensured more protection for the king's body. On his brow is the kingly uraeus: the Wadjet or rearing cobra, representing Lower Egypt, combined with the vulture Nekhbet of Upper Egypt. The combination of the two is symbolic of his domination of both lands" (quoted from the Egyptian Museum, Cairo).

This work also reflects the incredible wealth of Ancient Egypt at the height of the New Kingdom period when Tutankhamun reigned. This mask was just one of the three layers (or coffins) which supported the ruler's mummified body. While there is a sensitivity evident in the face of this young ruler, who became king at eight and died just a decade later, the general effect of the visage, according to Fred Kleiner, "is one of grandeur and richness expressive of Egyptian power, pride, and limitless wealth."

Gold and semiprecious stones - Egyptian Museum, Cairo, Egypt

Mummy Case

This highly detailed wooden sculptural figure served as a coffin for an unidentified ancient Egyptian. According to Denver Art Museum, "hieroglyphs were painted on both the inside and outside of the case, providing prayers for protection and praise for the individual in the afterlife." The surface of the coffin shows "many ancient Egyptian symbols of death and rebirth....Below the falcon collar is Nut..., the sky goddess and mother of Osiris..., god of the underworld and symbol of resurrection and immortality." The coffin also features images of Anubis, god of mummification, usually represented with the head of a jackal and the body of a man, but is shown here as a full jackal.

The appearance of Anubis is particularly significant. He was "the guardian of the cemetery", protecting the mummy in its tomb. Anubis would also oversee the ritual of embalming. While beautiful, the mummy case was thus painted with details that were essential to honoring the gods so that they would ensure a successful afterlife.

The rich detail on this work indicates that this mummy case appears at a late stage in the development of Egyptian funerary art. Denver Art Museum notes that "when this case was made, there was an increase in realism in Egyptian art. There is distinct modeling in the face on the surface of this case, but we don't know whether those who made the image intended for it to represent a portrait of the deceased, or a more generalized visage." The intense detail of the work, and the possibility of it containing an actual portrait, points to the subsequent emergence of highly realistic mummy portraits during the Roman occupation.

Cedar wood - Denver Art Museum, Denver, Colorado

Beginnings of Ancient Egyptian Art

Predynastic Period - Earliest Ancient Egyptian Art

The great prosperity of the Ancient Egyptian civilization was partly due to its location in the rich fertile lands on either side of the Nile River. According to the Czech egyptologist Jaromir Malek, "Ancient Egyptian civilization owed its existence to the favorable ecology that prevailed in the northeastern corner of Africa for several thousand years before the emergence of the kingdom of Upper and Lower Egypt around 3000 BC. Ancient Egypt was created by the Nile: the river was the most important contributor to economic life, and the country's very survival depended on the agricultural production which the Nile made possible."

The earliest traces of an Egyptian presence around the Nile date back to the Predynastic Period (6000 - 3150 BC). Very little is known of life in this era and there is not believed to have been any royal hierarchy of the type which dominated later Ancient Egyptian life and culture. Instead, during this Neolithic period of Egyptian history, the community was largely focused on agricultural production. According to Malek, they "lived in permanent settlements on the margins of the Nile Valley or the levees of the Delta". The Predynastic Egyptians made pottery and basketry, and are believed to have mastered the art of weaving.

The art produced during this early period was not large or detailed. But its existence supports the idea that personal adornment and decoration was important even in the earliest period of Ancient Egyptian civilization. What remains from this period is small in size, bearing little detail, such as bracelets and necklaces and loosely rendered animal-shaped cosmetic palettes. These were used to mix pigments worn on the face and body. Pigments in the Ancient Egyptian era were created in an array of colors, from materials such as iron, copper, and cobalt, mixed with liquid binders.

While simple in their form, Predynastic art laid the foundation for what would come. According to Malek, "the indisputable link between the humble artistic productions of the Predynastic Period and the perfection of pharaonic art can be traced, for example, in images drawn from the natural world, which were the most common motifs of Predynastic art. Among items of daily use, combs and cosmetic palettes provide the clearest links with later art."

Art of the Early Dynastic Period

The years 3150 to 2575 BC mark the Early Dynastic Period of Ancient Egypt, beginning with the unification of the upper and lower parts of the kingdom. At this time we find the first recorded references to gods and kings, the earliest ruler being King Narmer. This period in Egyptian art is defined by an increasing emphasis on detail and figurative representation.

One factor contributing to the increase in artistic production was the formation of different social classes. Even the most functional of objects needed to be designed for a particular social group, with more elaborate and detailed work for those in the highest positions, including the earliest rulers. For instance, while cosmetic palettes (used to grind and apply ingredients for facial or body cosmetics) were present in the Predynastic period and their function remained the same as before, these objects now became detailed works of art in some cases, incorporating images of gods, figures, and animals. This is clear from the Two Dogs Palette (3000BC), an example of the palletes which would have been used by the most important people in Ancient Egyptian society.

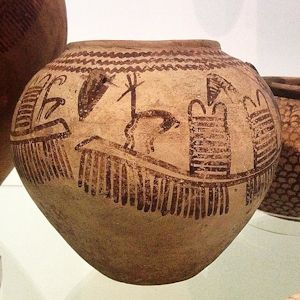

Pottery was another important aspect of the artistic production of this period. Works of pottery are believed to have been used in funerary practices, as many have been found in graves. The importance of the afterlife and the role that artmaking played in Egyptian religious practices can be seen even from this early period, then. According to Malek, "many of these pots have never been used: they were specially manufactured as grave goods, and show that workshops providing tomb furnishing, which were such a typical feature of the ancient Egyptian funerary scene, were not an invention of the pharaonic period."

Pottery of the Early Dynastic Period was often painted with scenes that provide a record of the typical animal life of the period, as well as showing the importance of the Nile to daily life. We find, for example, simple but recognizable depictions of men rowing boats on the water. As Malek explains, "these were the beginnings of Egyptian painting, which was to flourish in such a spectacular fashion on later tomb walls."

Several characteristics of later Egyptian art were carried down from the Early Dynastic Period. For example, it was at this time that figures began to be differentiated in size to represent social status, and perspective introduced. Egyptian art also began to acquire the quality of regularity and conceptual clarity that the influential twentieth-century art historian E.H. Gombrich would associate with it. In The Story of Art he states: "Egyptian art is not based on what the artist could see at a given moment, but rather on what he knew belonged to a person or scene". In other words, the essential features had to be recorded in a way that would hold true across eternity, not the passing appearance or feeling of a thing. For Gombrich, this set it apart from Ancient Greek art.

Early Dynastic Period Architecture

During the Early Dynastic Period, the first recognizable forms of Ancient Egyptian architecture appeared. The importance of death and what happens afterwards was evident even before this period, as indicated by the art found in graves. But elaborate tombs now began to be constructed for the purpose of celebrating one's death. These tombs were known as mastabas. They consisted of rectangular structures made of rows of stone bricks placed over underground burial rooms.

According to historian Fred S. Kleiner, "the main feature of these tombs, other than the burial chamber itself, was the chapel, which had a false door through which the ka [the soul of the dead] could join the world of the living and partake in the meals placed on an offering table. Some mastabas also had a serdab, a small room housing a statue of the deceased."As with the art of the period, distinctions within architectural structures were required to show the relative social status of certain figures.

After the development of the basic mastaba structure during the Early Dynastic Period, a series of stepped mastabas were designed. These were arranged in decreasing size. In these architectural forms we can see the origins of the design of the later pyramid.

Art of the Old Kingdom

There were three important periods of artistic development in Ancient Egypt: the Old, Middle, and New Kingdoms. The first of those creative periods, the Old Kingdom, covered the years from 2575 to 2134 BC.

Sculpture was one of the key outputs of the Old-Kingdom period. According to Kleiner, "Old Kingdom sculptors were called upon to produce statues in significant numbers because they fulfilled an important function in Egyptian tombs as substitute abodes for the ka if the embalmed corpse deteriorated....Egyptian sculptors worked with wood, clay, and other materials, but most of the many preserved funerary statues are of stone."

The subjects of these sculptures included gods, kings, and high-status figures in kings' inner circles. The works were block-like in style, with figures rendered either seated or standing, appearing formal and rigid in either case. A difference between the depiction of gods and rulers and other figures is that the former are presented as completely physically flawless, an outward sign of their perfection.

Carved and painted relief sculptures also became popular in this period. According to historians Rose-Marie and Rainer Hagen, "the relief was perfected during the Old Kingdom. In contrast to Greek reliefs, where the figures were worked three-dimensionally almost like statues, Egyptian reliefs basically remained a form of two-dimensional art. Composition and style resemble...paintings. There were two forms: in raised reliefs the surrounding area was chiseled away, while the figures stood slightly proud of the surface; in sunken or incuse reliefs, the figures were modelled in an equally shallow manner, but the surrounding area remained intact. Sunken reliefs with deeply cut lines created a strong shadow effect and for that reason were popular on the outer walls of temples exposed to sunlight."

Painted carved reliefs were also popular on the interior walls of mortuary tombs, where they were to provide visual pleasure for the deceased's ka when it returned to the earthly world. Scenes often featured celebrations as well as narratives of hunting which represented the triumph of good over evil.

Architecture of the Old Kingdom

While the Early Dynastic Period saw the development of the first stepped pyramids, it was during the Old Kingdom that the first true pyramids were created. To this day, the method of their construction remains a mystery. According to historian Becky Little, "researchers in Egypt discovered a 4,500-year-old ramp system used to haul alabaster stones out of a quarry, and reports have suggested that it could provide clues as to how Egyptians built the pyramids....Most Egyptologists already think that Egyptians used ramp systems to build the pyramids, but there are different theories about what types they used.[Kara] Cooney says experts have theorized they could've used straight ramps that went up the pyramid's outside walls, ramps that curved around these walls or ramping systems inside the pyramid itself."

Three huge pyramids were built during this period to serve as burial tombs for the Fourth Dynasty kings Khafre, Khufu, and Menkaure. Their triangular design was strongly linked to the gods. According to Kleiner, these shapes "represent the culmination of an architectural evolution that began with the mastaba, but the classic pyramid form is not simply a refinement of the stepped pyramid. The new tomb shape probably reflects the influence of Heliopolis, the seat of the powerful cult of Re [or Ra, the sun god] whose emblem was a pyramidal stone, the ben-ben."

Kleiner continues, "the pyramids are symbols of the sun. The Pyramid Texts, inscribed on the burial chamber walls of royal pyramids beginning with the Fifth Dynasty pyramid of Unas, refer to the sun's rays as the ladder that the god-king uses to ascent to the heavens....The pyramids were where Egyptian kings were reborn in the afterlife, just as the sun is reborn each day at dawn."

Art of the Middle Kingdom

The Middle Kingdom period in Ancient Egypt covered the years 2040 to 1640 BC. This period followed a time of great unrest ending with the reunification of Egypt under one ruler, King Mentuhotep II. There was also a change in how kings were perceived, the sense of distance between them and the gods increasing slightly. According to Rose-Marie and Rainer Hagen, the instability of the recent past "shook the trust in an order created by the gods and maintained by a divine pharaoh. After the pharaohs had been demoted to god-sons they came closer to human beings."

The period was also marked by a change in the nature of spirituality and accompanying architectural preoccupations, as the Hagens note: "the belief in pyramids as ladders to heaven waned, while interest in the underworld and its ruler Osiris grew. This was not only caused by a darkening of their world view, but also...by a growing self-confidence of the elites. At one time it was only kings who could rise to heaven. The paradise of the underworld was [now] open to all who passed the Judgement of the Dead as 'justified'. It was not just kings, but many others who had the right to eternity."

This change in culture and religion led to changes in artistic style. Perhaps in line with a new sense of the rulers' mortality, their figurative depictions became more naturalistic. Artists no longer showed rulers with perfect facial features. However, their bodies often remained flawless and rigid in appearance.

Demand for sculptural representation remained great amongst rulers of the Middle Kingdom. Many commissioned depictions of themselves not merely as divine human forms, but as cryptid or composite creatures such as the Sphinx. According to Rose-Marie and Rainer Hagen, "not just kings, but also gods were represented as mixed creatures. However, whenever gods or goddesses were depicted, the body was usually human and only the head was that of an animal....The opposite was true for pharaohs. The head identified a person, while the lion's body symbolized superhuman power." In this way, viewers were reminded of the pharaoh's otherworldly power and divine right to rule (in spite of their less overtly divine status than during the Old Kingdom).

By the time of the Middle Kingdom, it was not just kings and the wealthy who were able to commission sculptures. With the increase in burial tombs for lower-class citizens, there was an increase in the need for works to fill them. According to Jaromir Malek, "the growing number of people who were able to afford funerary arrangements in the first half of the second millennium BC can be seen in the increase in modest tombs and graves of the period. Many of these tombs were little more than a small vaulted superstructure built over the mouth of the tomb shaft. Such tombs did not have a special statue room: sculptures representing the dead person now accompanied the body into the burial chamber. These statues were small, and although they often have considerable charm, their craftsmanship is rather commonplace."

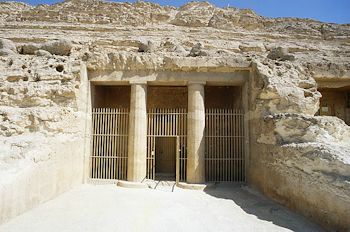

Architecture of the Middle Kingdom

During the Middle Kingdom, funerary tombs remained the most culturally and politically significant architectural form. The idea of creating a home for the deceased's ka to visit had remained central to Egyptian religion. Mastabas, by contrast, fell out of fashion. Most Egyptians preferred to carve their tombs out of, and into, rockfaces. Kleiner notes that such tombs were often "hollowed out of the cliffs, the most elaborate examples, such as the 12th Dynasty tomb of Khnumhotep II, hav[ing] a shallow columnar porch, which leads into a columned hall and then into a burial chamber featuring rock-cut statues of the deceased in niches, and paintings and painted reliefs on the walls."

Art of the New Kingdom

The close of the Middle Kingdom was marked by another great upheaval in Ancient Egyptian culture, including attacks from neighboring civilizations. But reunification came again, this time under the rule of Pharaoh Ahmose I, leading to a restoration of peace and order. The New Kingdom spanned the years from 1550 to 1070 BC. The gods continued to exert great control over how life was conducted in Egypt. It was also during this period that kings became known as pharaohs.

One of the unique developments in sculpture during the New Kingdom period was the emergence of the block sculpture. Previously, sculptures depicting rulers had a rigid formality, as if the core of the human body consisted of a block or solid structure. In the New Kingdom, this idea was formalized to the extent that figures were literally represented with blocks of stone for bodies. According to Kleiner, "block statues were popular during the New Kingdom because their large flat surfaces were well suited for lengthy inscriptions and because their simple shapes were easier to carve and less susceptible to damage. These works display an even more radical simplification of form than was common in Old Kingdom statuary, but they performed the same function - the provision of an eternal home for the deceased's ka."

Concerns about the nourishment and enjoyment of the ka continued to be important during the New Kingdom period. As in earlier periods, painted frescoes on tomb-walls were one way to keep the deceased's soul entertained. The works created were more elaborate than in earlier periods, with more realism, often showing complex scenes such as large hunting parties. Such frescoes also had strong allegorical values. According to James W. Singer, scenes of hunting, such as that which appears in the tomb of the scribe Nebamun and includes dead birds, often connected the successful hunt with "triumph over evil because the wild fish and birds symbolize chaotic forces, evil in the Egyptian psyche."

Reign of Akhenaton and the Elevation of Aton the Sun God in Art

While Ancient Egyptians worshipped many gods, there was a period during the New Kingdom when one specific god, Aton, became exclusively revered and worshipped. When Pharaoh Amenhotep IV (also known as Akhenaton) came to power in 1353 BC, he made a policy of rejecting all gods but Aton (the sun god). Akhenaton also oversaw a change in sculptural style, moving away from rigid formality of earlier figurative likenesses to a more curvaceous, sensual flow of lines. According to Kleiner, Akhenaton "abandoned the worship of most of the Egyptian gods in favor of Aton, identified with the sun disk, whom the pharaoh declared to be the universal and only god....Akhenaton's religious revolution was accompanied by a break with artistic tradition, seen both in portraiture and relief sculpture."

Pharaoh Tutankhamen and His Tomb

Perhaps the best known ruler in all of Pharaonic history, Tutankhamun also had one of the shortest reigns. Becoming king at the age of eight, he ruled during the New-Kingdom era for a decade before dying from unknown causes. His impact on contemporary appreciation of Ancient Egyptian art is his lasting legacy, however. The riches of Tutankhamun's tomb were unearthed in 1922 by a British archaeologist, Howard Carter. The burial chamber contained an abundance of works in gold, including the pharaoh's coffin, which was also lined with precious gems and stones.

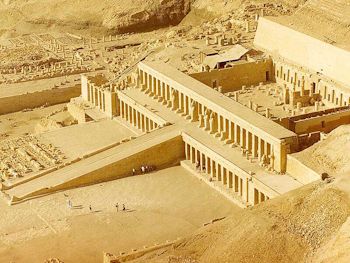

Architecture of the New Kingdom

Architecture continued to play an important role in Egyptian artistic culture during the New Kingdom period. Kleiner notes that "if the most impressive monuments of the Old Kingdom are its pyramids, those of the New Kingdom are its grandiose temples. Some of these temples were built to worship the state gods, but others were mortuary temples, which provided the pharaohs with a place for worshiping their patron gods during their lifetimes and then served as temples in their own honor after their death. The greatest mortuary temples arose along the Nile in the Thebes district during the 18th and 19th dynasties."

The pharaohs sought to emphasize their power and divine right to rule through the elaborate design of their mortuary temples. One impressive example was the mortuary temple of the female pharaoh Hatshepsut. Describing the massive structure, Kleiner states, "Hatshepsut's temple rises from the valley floor in three column-lined terraces connected by ramps on the central axis. It is striking how well Senenmut [the pharaoh's chancellor, whom most believe to be the architect of the temple] designed the complex to complement its natural setting. The long horizontals and verticals of the colonnades and their rhythm of light and dark repeat the pattern of the limestone cliffs above." The connection between art and architecture is evident in Hatshepsut's temple, as during her lifetime she filled it with statues of herself.

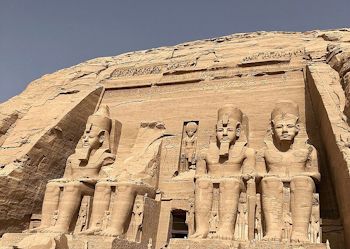

It was not only in the interiors of mortuary temples that figurative sculptures could be sited to honor the pharaohs. During the Middle Kingdom, some rulers had their likenesses carved on the exteriors of their temples, too as with Pharaoh Ramses II. He opted for not one, but four statues of himself, all identical. As well as suggesting the colossal ego of a monarch who believed himself divinely ordained, this indicates the extent to which architecture can assert and reinforce a ruler's power and prerogative. According to Kleiner, "the king, proud of his many campaigns to restore the empire, proclaimed his greatness by placing four colossal images of himself on the temple façade. The portraits are 65 feet tall - almost a dozen times the height of an ancient Egyptian, even though the pharaoh is seated. They face toward Nubia and served to intimidate the Egyptian's southern neighbor."

Concepts and Styles

Ancient Egyptian Art and the Afterlife

Ancient Egyptians did not believe that life ended upon one's death. They devised a rich afterlife that could be aspired to, and art played an important role in helping to ensure a pleasurable eternity.

Ancient Egyptians believed that there were five parts to one's soul, the Ren, Ka, Ib, Ba, and Sheut. The Ren consisted of the person's given name. The Ib was their heart, which would be weighed upon death. The Sheut was the person's shadow, which would remain with them always. The Ba consisted of the person's character, the qualities that made them unique. The most important element, the Ka, consisted of the spirit, essence, or soul of the individual. It was the Ka that left the body during death, and could return to interact with the living within the tomb.

It was important that food and drink were left in the tomb for the Ka, as well as pleasing and celebratory art on the walls. Large-scale figurative sculptures also needed to be left in the tomb, as places for the Ka to inhabit. According to Malek, "public display and accessibility were ... considerations for much of the art made for tombs. Here, a statue placed in a closed statue room provided the required physical abode for the deceased's ka (soul or spirit) which continued to exist even after death. Artistic requirements would be difficult to grasp without understanding the statue's purpose: for example, the representation had to be sufficiently lifelike and identifiable so that the ka would recognize its own statue."

Mummification

While the soul, or Ka, of an Ancient Egyptian was essential to a good afterlife, the way a deceased person's body was treated was equally important. According to Kleiner, "the Egyptians did not make the sharp distinction between body and soul that is basic to many religions. Rather, they believed that from birth a person possessed a kind of other self - the ka - which, on the death of the body, could inhabit the corpse and live on. For the ka to live securely, however, the body had to remain as nearly intact as possible. To ensure that it did, the Egyptians developed the technique of embalming (mummification) to a high art."

The mummification process was probably initially accidental, with bodies preserved by sand and dry desert air in shallow pits. But the process became formalized during the Fourth and Fifth Dynasties, continuing for well over 2,000 years. Differences in the quality of mummification depended on social status, with the best preserved bodies being those of the ruling classes. In all cases, the process took around 70 days. Internal organs that might decay were pulled out and preserved in canopic jars. The body was then dried out with salt and wrapped in hundreds of yards of linen with periodically applied layers of warm resin.

Art objects played a key role in several steps of the mummification process. As Julie St. Jean describes, "the lungs, stomach, liver and intestines were placed inside four different canopic jars. The purpose of which was to ensure the dead had access to them in the afterlife. These jars were carved from limestone or made of pottery and generally had heads of specific gods (the four sons of Horus-the god of the sky and the one who protects the pharaoh) and were protected by the corresponding goddesses." Further artworks, including amulets to ward off evil spirits and jewelry, were often placed on the body. After mummification was complete, the entire body was placed in an elaborately painted coffin of figurative shape.

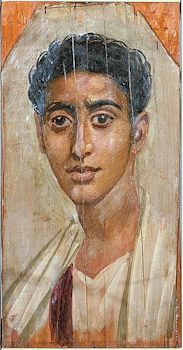

Much later, when Egypt fell under Roman control following the Battle of Actium in 31 BC, these native death rituals had to be significantly curtailed or conducted in secret. At this point, portraits of the deceased placed on wooden panels became more common. These were not combined with representations of gods or hieroglyphics on coffin covers, as had been common in the past. The newer mummy portraits are now renowned for their high realism, showing the likeness of the deceased's mummified body.

As Caroline Cartwright notes, however, "although these mummy portraits became very popular in the first to third centuries AD in Egypt, people there still mummified human bodies as they had always done, burying them in sealed tombs. Two traditions were fused: the old and the new. The mummy portrait was secured in linen wrappings or in a cartonnage (layers of linen mixed with plaster) and placed over the face of the underlying mummy."

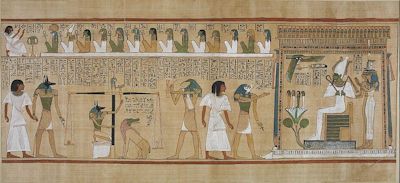

Art was also connected to the afterlife through its use in the so-called Book of the Dead. As Sara E. Cole explains, the Book of the Dead "is a modern term to describe a series of ancient Egyptian ritual spells....These helped the deceased find their way to the afterlife and become united with the sun god Re and the netherworld god Osiris in a continual cycle of renewal and rebirth. There are nearly 200 known spells, but they weren't collected into books in our current sense of the word. Rather, assemblages of spells were inscribed on objects from mummy wrappings to coffins to figurines to papyrus scrolls, all meant to accompany the dead in the tomb. They provided instructions for the various challenges the deceased would face on their journey."

Art was important in two ways in relation to the Book of the Dead. Firstly, in many cases, the spells used to ensure a successful passage through the afterlife were recorded in the form of beautiful visual narratives. In addition, artistic symbols were used in conjunction with hieroglyphic text to explain the spells in accompanying panels or annotations.

Ancient Egyptian Art and Religion

Every aspect of Ancient Egyptian life was tied to religion, and more specifically to the gods. Rulers were in fact seen as being uniquely able to communicate with the gods, as Malek explains. "Egyptian religion comprised a diverse system of beliefs about the gods, and the king's links to them. It offered an explanation of the cosmos and a concept of life after death....Egyptian temples were intended not for popular worship but to provide a place where the king could commune with the gods; they were closed to everyone else, regardless of social standing."

Given the importance placed on the gods, the Ancient Egyptians relied on depictions of deities in their art from the earliest days of their civilization. Such images can be found in freestanding sculptures, reliefs, and paintings on mummy cases and tomb walls. As Egyptians believed both gods and the dead could visit the mortal world, it was important that beautiful artworks were present to welcome and entertain them.

Egyptian gods were multiple in both number and visible forms, as Malek explains. "One of the most striking features of Egyptian religion was the multiplicity of its deities, each of which could manifest itself in a variety of forms - as a living animal or bird, or as a man-made image which could be anthropomorphic (in human form), zoomorphic (in animal form), a combination of the two, or in some inanimate or vegetal form."

Malek adds that the Pharaoh himself (or, sometimes, herself) was seen as semi-divine. "The pharaoh ... was not regarded as a fully-fledged god [but] was not an ordinary mortal either. As netjer nefer ('junior god'), he shared the gods' designation netjer and was seen as a personification of the god Horus and the son of the sun god Re."

Art and Writing in Ancient Egypt

Ancient Egyptian art is notable for combining writing and visual forms in ways that make the precise boundaries between the two hard to fix. Many architectural or sculptural structures are inscribed with densely ranked hieroglyphics. By contrast, in many cultures, the appearance and function of writing and visual expression are clearly separate, suggesting two distinct modes and traditions.

This is due to two factors. On the one hand, it reflects the common role of art in Ancient Egypt to record the great deeds of rulers, and other narratives of human achievement. This could be more easily achieved when written annotations or captions were included alongside visual forms. But it also reflects the fact that writing in Ancient Egypt was much more closely connected to visual art than it is in the English-speaking world of the twenty-first century.

Hieroglyphic writing, like all early writing systems, emerged out of pictography. This means that it began as a series of simple visual representations of people, animals, objects, actions, and concepts. Eventually, some of these written symbols came to stand not for the thing itself, but for the sound which referred that thing when people were speaking. This marked the start of phonetic writing. And, once writing began to refer to sounds rather than appearances, its pictorial visual qualities were gradually lost. But Hieroglyphics occupy a very early point on this spectrum of development. So they still seem very much like sequences of pictures: miniature, diagrammatic versions of Ancient Egyptian visual art, in fact.

This overlap becomes fascinating when we remember that our own, English written language uses the Roman Alphabet, which has distant roots in Hieroglyphics. Our letter A, for example, evolved out of an Egyptian glyph representing an ox's head. Therefore studying Hieroglyphics can remind us of the origins of our own, modern writing system in visual art.

Later Developments and Legacy

The power of Ancient Egypt came to wane after the end of the New Kingdom period in 1070 BC. From this point onwards they were subject to the controlling influence of several enemy nations such as the Kingdom of Kush and the Assyrians. According to Kleiner, "during the first millennium BC, Egypt lost the commanding role it had once played in the ancient world. Egypt's fertile lands and immense riches had long made it desirable territory. Foreign powers invaded and occupied the land, and the empire dwindled away until, beginning in the fourth century BC, Alexander the Great of Macedon and his Greek successors and, eventually, the emperors of Rome replaced the pharaohs as rulers of the Kingdom of the Nile."

However, these conquering civilizations could not help but be influenced by the rich artistic traditions of Ancient Egypt. Examples can be found in the art created in the Kingdom of Kush, for example. After conquering Egypt, Kush rulers commissioned likenesses of themselves in statuary form as Egyptian sphinxes.

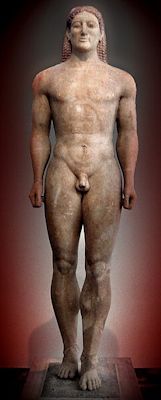

Beyond the cultures that conquered it, Ancient Egyptian art and architecture had a profound impact on future civilizations which is still being felt today. This is particularly clear in the case of sculpture. Ancient Egyptians statuary had a profound impact on Ancient Greek sculpture, for example, which in turn underpinned the whole development of Western three-dimensional art. While the Greeks freed their figurative sculpture from the static solidity of Egyptian sculpture and perfected capturing movement in marble, the intense realism and forward stance of Ancient Egyptian sculpture seems to have formed the basis for Greek kouros (male) and kore (female) sculptures.

Sebastian Maydane offers some context for this view. "Among art historians, it was once common practice since the times of Johann Winckelmann to distinguish between the 'naturalistic' style of Egyptian art and the much more refined and generally superior style of Greek art. However, nowadays this prejudice is contested and it is commonly accepted that Egyptian art was not inferior to Greek art and in fact the latter owes a lot to the former. For instance, the archaic monumental statues of young men known as kouroi...provide evidence of Egyptian influence, not only in the proportions and techniques used but also in the posture of the human body as well. Egyptians statues of standing men would invariably have the depicted individual standing not with the two legs parallel but with one foot forward. This created a sense of dynamism which was copied by the Greeks and perfected generation after generation."

Knowledge of and interest in Ancient Egyptian art increased greatly after the discovery of the young pharaoh Tutankhamun's tomb by British archeologist Howard Carter. The riches exhibited following this discovery allowed the world to see the extraordinary sumptuousness and sophistication of Ancient Egyptian design. The art found in the tomb of "King Tut" also had a profound impact on early-twentieth-century artistic culture.

Of this influence, Nicky Hughes states: "as the exquisite beauty and richness of the more than 5,000 grave goods were revealed, the world was mesmerised. 'Egyptomania' swept the globe. The discovery inspired Ancient Egyptian-style design, nationally and internationally, in architecture, furnishings, fabrics, fashion, jewellery, hairstyles, art, interior design and popular culture, becoming an integral part of the visual language of Art Deco, a decorative arts style that would dominate until the mid-1930s."

Within architecture, the Art Deco movement was inspired by Ancient Egyptian art in its use of symmetry, its emphasis on curvaceous lines and forms, its hieroglyphic-style markings, and its red, blue, and green color palette. One excellent example is the Greater London House. Built in 1926, it was originally known as the Carreras Building and served as a factory for the production of tobacco. As Hughes explains, "the Art Deco Carreras cigarette factory references the red, blue and green colours of Ancient Egypt, albeit in muted form, as well as many of its motifs and symbols, such as its twelve pillars with their papyrus bud capitals and stylized papyrus stems at the base of their shafts. The company's name 'Carreras' on the frontage is carved in a font loosely reminiscent of hieroglyphics. Two enormous black bronze cats, 3.6 metres high, guard the entrance. These both reference the Ancient Egyptian cat goddess, Bastet, as well as Carreras' then best known cigarettes, 'Black Cat.'"

The pyramids are another achievement which has had an incredible influence on future civilizations that can still be felt today. According to Joyce Tyldesley, "Egypt's magnificent stone buildings - her pyramids and temples - have inspired innumerable artists, writers, poets and architects from the Roman period to the present day. The pyramid form, in particular, still plays an important role in modern architecture, and can be seen rising above cemeteries and innumerable shopping centres[sic], and at the new entrance to the Louvre Museum, Paris."

Useful Resources on Ancient Egyptian Art

- Egyptian ArtOur Pickby Bill Manley

- Egyptian ArtOur Pickby Jaromir Malek

- Egypt: People, Gods, Pharaohsby Rainer Hagen and Rose-Marie Hagen

- Egyptian ArtOur Pickby Rainer Hagen and Rose-Marie Hagen

- Gardner's Art through the Ages: A Global History, Volume 1, 16th EditionOur Pickby Fred S. Kleiner

- The Story of ArtOur PickBy E.H. Gombrich

- Art and IllusionOur PickBy E.H. Gombrich

Ask The Art Story AI

Ask The Art Story AI