Summary of Byzantine Art and Architecture

Existing for over a thousand years, the Byzantine Empire cultivated diverse and sumptuous arts to engage the viewers' senses and transport them to a more spiritual plane as well as to emphasize the divine rights of the emperor. Spanning the time between antiquity and the Middle Ages, Byzantine art encompassed an array of regional styles and influences and developed long-lasting Christian iconography that is familiar to practitioners today.

Because of its longevity and geographical scope, Byzantine art does not necessarily proceed in a linear progression of stylistic innovations. Its origins in the Roman Empire meant that even in the face of unclassical tendencies that favored hierarchical compositions and symbolic meanings there were periods of revival that emphasized more naturalistic renderings that foregrounded storytelling. Within this milieu, distinctive styles of mosaics and icon paintings developed, and innovations in frescos, illuminated manuscripts, and small-scale sculptures and enamel work would have lasting influence not just in Eastern realms such as Turkey and Russia but also in Europe and even in contemporary religious painting.

Key Ideas & Accomplishments

- In further developing Christian iconography that began during Roman times, images became powerful means to spread and deepen the Christian faith. Many of the now-standard iconographic types, such as Christ Pantocrator and the Virgin and Child enthroned, were created and evolved during the Byzantine era. This new-found power of images, however, was not without controversy and sparked a heated and, at times, violent debate over the place of images in the church.

- Byzantine emperors used art and architecture to signal their strength and importance. Often, depictions of the emperor were less naturalistic and instead used compositional clues such as size, placement, and color to underscore his importance. Additionally, the emperor was often visually associated with Christ, making it clear that his power was divinely ordained and, thus, secure.

- Beginning with the basilica and central plans used by the Romans, Byzantine architects and designers made huge engineering innovations in erecting domes and vaults. The use of pendentives and squinches allowed for smoother transitions between square bases and circular, or octagonal, domes.

- The architectural surfaces of Byzantine churches were covered in mosaics and frescoes, creating opulent and magnificent interiors that glittered in the candle and lamp light. In building such elaborate and seemingly miraculous structures, the goal was to create the sense of a heavenly realm here on earth, a goal that later Gothic architecture fully embraced.

Artworks and Artists of Byzantine Art and Architecture

The Hagia Sophia

In Istanbul, the Hagia Sophia's most prominent and celebrated feature is its large dome, soaring above the city, while its square brick edifice and two massive towers, create an impression of fortress-like solidity. The interior is equally renowned for its light-filled space that creates a heavenly atmosphere. As the Emperor Justinian's biographer Procopius wrote at the time, "Yet [the dome] seems not to rest upon solid masonry, but to cover the space with its golden dome suspended from Heaven." The dome is the largest in the world, made possible by the architects' pioneering use of pendentives; the corners of the dome's square base curve up into the dome and redistribute its weight. The architects also inserted forty windows around the base of the dome, lightening the weight of it and illuminating the interior. They gilded the frames of the windows so that the stone refracts and reflects the light, making it appear that the dome is floating. When the church was completed, Justinian supposedly exclaimed, "Solomon, I have outdone thee!"

In 532 Justinian I appointed Isidorus of Miletus and Anthemius of Tralles to rebuild the church. The previous church had been destroyed in rioting against Justinian's government, and its consecration was meant to mark the restoration of his central authority. At the same time, as the seat of the Ecumenical Patriarch of Constantinople, the church also symbolized the spiritual authority of the Orthodox church. The structure of the interior also communicated social hierarchies, as the ground floor and upper gallery were segregated according to gender and social class with the gallery reserved for the emperor and other notables. Similarly, the entrance to the nave of the church contained nine doorways with the Imperial Door, reserved for the emperor, in the center. In effect, the church was a concrete schemata of the religious, political, and social organization of the empire - an earthly but heavenly city.

In 1453 following the Turkish conquest, the building became a mosque, and the four minarets, each over 200 feet tall, were added. Interior mosaics were painted over in gold and replaced with large medallions inscribed with calligraphy. Nonetheless the building's original design was much admired, as shown by the Ottoman historian Tursun Beg who wrote in the 15th century, "What a dome, that vies in rank with the nine spheres of heaven! In this work a perfect master has displayed the whole of the architectural science." The church became a model for Ottoman architecture, as seen in the Sultan Ahmed Mosque (1609-1616), popularly known as the Blue Mosque. Today the Hagia Sophia is a national museum, in order to remove it from the religious controversies that are still associated with the site today.

Brick, mortar, stone, marble - Istanbul, Turkey

Barberini Diptych

This ivory relief was originally a diptych, hinged to another panel that was subsequently lost. Two smaller panels - the right one also lost - frame the central depiction of an energetic emperor, likely Justinian, on horseback. As the muscular and dynamic horse rears on its hind legs, the emperor looks forward as he grasps the shaft of a lance in his right hand and with his left grasps the horse's reins. Around him, three smaller figures symbolize his power and dominance. The winged figure of Victory on the upper right stands on a globe inscribed with a cross, holding a palm branch, another symbol of victory, in her left hand while her right hand crowns the emperor. A defeated barbarian stands on the left behind the horse, and a partially nude woman, who holds a cornucopia in her lap and reaches out to grasp the emperor's foot with her right hand, symbolizes the earth.

In the upper panel, two heraldic angels hold a central medallion depicting Christ holding a cross and flanked by symbols of the sun, moon, and stars. In the left panel, a soldier, holding a statuette of Victory, turns toward the emperor. The lower panel depicts two Western barbarians on the left and two Eastern barbarians on the right, all bringing tribute, including ivory tusks, lions, tigers and elephants, to another winged Victory figure at the center who gestures toward the emperor above. Every element reiterates imperial authority and is innovatively depicted with energetic compression; the figures seem to surge within the frame. The model for this small portable work was the famous equestrian statue of Marcus Aurelius, but rather than the stoic strength of that work, this depiction makes the emperor "brim with the same energy as his charging stead," as the Jansons wrote.

The Early Byzantine era pioneered ivory reliefs, which had a long-lasting influence upon Western art. They were much prized by the European elite, and this particular piece is now named after Cardinal Barberini, a noted 17th-century art patron and collector. Created during the reign of the Emperor Justinian, the work also exemplified the Early Byzantine style, which still drew upon classical influences, as the figure of the emperor and his horse, the lance, and the winged victory are carved in such high relief that they seem fully three dimensional. The surrounding panels are carved in shallower relief, visually emphasizing the emperor as the source of energy and power. The message of the work was also innovative as it combined the military victory of the emperor with the victory of Christianity, employing two angels carrying an image of Christ rather than the Roman era's use of a pair of winged Victories. As art historian Ernst Kitzinger wrote, "Christ makes his appearance in heaven at the moment in which the emperor stages his triumphal adventus on earth. It is a graphic depiction of the harmony between heavenly and earthly rule."

Ivory - Musée du Louvre Museum, Paris, France

Emperor Justinian Mosaic

This famous mosaic depicts the Emperor Justinian I, haloed, wearing a crown and an imperial purple robe and holding a large golden bowl for the bread of the Eucharist. Carrying a gold cross, Bishop Maximianus of Ravenna, whose name is inscribed above, stands on the emperor's left along with three other clergy, one holding a incense censor and the other a gilded Gospel. On the emperor's right stand two men in white robes with a purple stripe, identifying them as members of the imperial administration, as well as a group of soldiers, gathered behind a single shield decorated with a cross. Placed in the center, the Emperor is thus depicted as the central authority between the power of the church and the power of the government and military.

The distinctive style of this mosaic defined Early Byzantine art. The naturalistic treatments of classical Greek and Roman art were abandoned in favor of a hierarchal style that, rather than drawing the viewer's eye into a convincing image of reality, presented figures with direct gazes that were meant to spiritually engage the viewer. This was one of two mosaics flanking the altar; the second depicts the Empress Theodora, similarly accompanied, and in both scenes the figures are shown as if they were bringing the gifts of the Eucharist to the altar that occupies the physical space between the mosaics. All of the figures are posed frontally in a distinctive figurative style, with tall thin bodies, tiny feet pointed forward, oval faces and huge eyes, and without any suggestion of movement. As the art historians H.W. Janson and Anthony F. Janson wrote, "The dimensions of time and earthly space have given way to an eternal present in the golden setting of Heaven. Hence the solemn, frontal images seem to belong to a celestial rather than a secular court. This union of political and spiritual authority reflects the 'divine kingship' of the Byzantine emperor."

Mosaic - San Vitale, Ravenna, Italy

Christ Pantocrator

This wooden panel, painted in encaustic, or colored wax, depicts Christ in a frontal view, his head framed by a halo which contains the shape of the cross. He raises his right hand in a gesture of blessing and holds a Gospel book, gilded with a jewel-inlay cross, in his left. The folds of his purple tunic and himation, a Greek garment, are modeled with darker and lighter shades of color. His figure, nearly life-size and filling the pictorial frame, combined with his calm and direct gaze, give the work a sense of immediacy that seems to impel him toward the viewer. The dark lines of his hairline, eyebrows, and eyes draw attention to his luminous face, while subtle white highlights, contrasting with deeper shadows, enliven his expression. Behind him, spatial depth is conveyed by the architectural framework and a low horizon line.

This image is the earliest surviving depiction of the Christ Pantocrator, meaning the "all-powerful," and set the precedent for the popular iconographic type that spread through Byzantium and eventually into Europe. It was painted in Constantinople and sent by Justinian I as a gift to honor the founding of the monastery located near Mount Sinai, the sacred site associated with the prophet Moses and the Ten Commandments. Due to its isolation and its distance from Constantinople, the monastery evaded the widespread destruction of art during the Iconoclastic Controversy and, therefore, is noted for its exceptional Early Byzantine artworks.

Encaustic on wood - Saint Catherine's Monastery, Sinai, Egypt

Virgin (Theotokos) and Child between Saints Theodore and George

This image depicts the Virgin seated in a golden throne, holding the Christ Child on her lap as if presenting him to the viewer. Dressed in white and holding a gold cross in his right hand, the haloed Saint Theodore, revered as a warrior saint and a martyr in the Orthodox church, stands to the Virgin's right, while Saint George in red, also haloed and holding a cross, flanks her left. All four figures are depicted in colorful, fine robes and face forward, stern and motionless, with prominent eyes confronting the viewer. The hierarchical composition elevates the Virgin slightly, and the gold edging of her chair sets her distinctly apart. With right knees bent as if to step forward, the saints reflect the influence of classical Roman art and convey the presence of a more human and material world in contrast to the Virgin's heavenly throne. Behind the figures, two haloed angels turn their heads in profile to gaze toward the hand of God, from which a triangular beam of light streams down, illuminating the Virgin's halo. The composition presents a complex interplay between the physical materiality of the saints and Mary and the near transparency of the angels and the divine, thus directing the viewer's meditation and prayer to the incarnation of God in Christ through Mary.

This icon is one of the earliest surviving examples of the Theotokos, or Mother of God, image that dominated Byzantine art and influenced Western art, particularly in the Gothic era's cult of the Virgin. It is also one of the earliest depictions of Saint Theodore and Saint George, who became revered saints not only in the Byzantine Empire but also in the West. The 4th century Theodore became the patron saint of Venice until the 9th century, and Saint George, believed to be a Roman soldier who was martyred for refusing to recant his faith, became the legendary dragon slayer of the medieval period, the patron saint of England, and the inspiration for countless art works.

Encaustic on wood - St. Catherine's Monastery, Sinai, Egypt

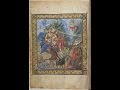

David Composing the Psalms

This illuminated page from the Paris Psalter depicts the Biblical King David, seated on a boulder in the center, as he plays a harp in a pastoral landscape. Portrayed as a young shepherd, he is surrounded by his flock that appears charmed by his music. A woman, wearing classical Greco-Roman robes and symbolizing Melody, sits beside David, while in the upper right, another female figure represents the Greek goddess Echo. In the lower right, a man representing the city of Bethlehem rests on the ground. While seemingly a biblical scene, the work evokes classical images of the story of Orpheus, a poet whose song had the power to charm both the forces of nature and the Greek gods. Its overall effect of a idyllic pastoral and its more realistic figurative treatment was a radical revival of classical aesthetics for the era.

Psalters were popular reproductions of the Bible's Book of Psalms, many of which were believed to be authored by King David. This particular work was unique for its large size, its high quality, and full-page illustrations, suggesting that it was made for an aristocratic patron. Containing 449 folios, or pages, and fourteen full-page illuminations, including eight scenes from King David's life, this work exemplified the Macedonian Renaissance with its realistic representations, depictions of landscape with plants and animals, and classical allusions.

Illuminated manuscript - Bibliothèque nationale de France, Paris, France

Anastasis (Harrowing of Hell)

This fresco depicts the Anastasis, or harrowing of Hell, an image frequently depicted in the Late Byzantine era that drew upon the Christian tradition that on Holy Saturday, between his crucifixion and his resurrection, Christ rescued Adam and Eve from hell. Here, Christ, dressed in white and surrounded by a luminous mandorla, or full body halo, energetically grasps Adam's and Eve's wrists as he pulls them from their tombs on either side of him. The dynamic and dramatic image was located in the funerary chapel of the monastery church in Chora, where a cycle of other paintings portrayed religious scenes of Christ's redemption of human sin and mortality.

Their vividly colored robes flowing about them, the three central figures move with a dynamic and swift smoothness that is further emphasized by the contrast with the stillness of King David and John the Baptist depicted on the left and various martyrs and saints on the right. The dark background above and below, where Satan, along with the locks and keys of Hell, is depicted as trampled beneath Christ's feet, further emphasizes Christ's dynamic movement and heavenly brilliance. The landscape, with its planes of gold and lack of detail, conveys that the figures inhabitate a spiritual space, an unchanging eternity that only Christ can alter.

The work is, as art historians H.W. Janson and Anthony F. Janson wrote, "a magnificently expressive image of divine triumph. Such dynamism had been unknown in the earlier Byzantine tradition. This style, which was related to slightly earlier developments in manuscript painting, was indeed revolutionary." The change in style was the outcome of humanism's influence (manifested later and powerfully in Rennaissance Humanism) that had begun in the Middle Byzantine period. Theodore Metochites, a poet and scholar who was Emperor Andronicus II's prime minster, restored the church and commissioned the paintings to reflect religious narrative and "the growing Byzantine fascination with storytelling."

Fresco - Church of the Holy Savior of Chora/Kariye Museum, Istanbul, Turkey

Holy Trinity Icon

This, the most famous of all Russian icons, depicts three angels seated around a table upon which sits a chalice containing the head of a sacrificed calf. The arrangement of the winged figures, the graceful lines, and the clothing they wear create a visual circle, symbolizing their unity. Both the angel in the middle and the one on the right lift their hands in gestures of blessing over the cup as they look toward the angel on the left. With this circular composition, Rublev conveys a sense of still contemplation.

The work ostensibly depicts the Biblical account of the visitation of three angels to the prophet Abraham, who sacrificed a calf to feed and honor his visitors, but more than an illustration of the story, the icon is a visual expression of the concept of the Trinity, the belief that God is one but in three persons - the Father, the Son, and the Holy Spirit. In the background, above the central angel, a single tree alludes to the Oak of Mamre where the visitation took place, but it also refers to the Tree of Life in the Garden of Eden and the cross upon which Christ was crucified, thus connecting the central angel with Christ. The relationship is further emphasized by the angel's red robe, the color that symbolizes Christ's Passion. The angel on the right wears the green associated with the feast of Pentecost, when the Holy Spirit descended upon Christ's followers, while God the Father sits on the left, his importance indicated by the gaze of the others turned toward him. The unity of the godhead is symbolized by the fact that all three of the angels wear blue garments, and they seem to be engaged in sacred conversation, conveyed by gaze and gesture, around the chalice that represents Christ's sacrifice. In the background, a house alludes to both Abraham's house and the home of eternal salvation, while the mountain suggests Mount Tabor, the Biblical site where the Holy Spirit descended. To convey the complex symbolic meaning, Rublev left out many of the traditional elements of the story that are usually depicted.

Though not a great deal is known about him, most scholars believe Andrei Rublev was a monk in the Holy Trinity Monastery. The monastery was and still is considered to be the spiritual heart of the Russian Orthodox Church. In 1551 the Russian Orthodox Church Council of the Hundred Chapters met to consider the iconographical canon and declared this icon was the model for all Orthodox icons. In an era of great discord and violence, Rublev's image also emphasized spiritual unity, mutual love, humility and peace. Rublev's reputation has only grown in the contemporary world. The noted filmmaker Andrei Tarkovsky's Andrei Rublev (1966) was based upon the artist's life, and in 1988 the artist was canonized as a saint.

Tempera on wood - Tretyakov Gallery, Moscow, Russia

Beginnings of Byzantine Art and Architecture

To Start: Defining the Byzantine Period

The term Byzantine is derived from the Byzantine Empire, which developed from the Roman Empire. In 330 the Roman Emperor Constantine established the city of Byzantion in modern day Turkey as the new capital of the Roman empire and renamed it Constantinople. Byzantion was originally an ancient Greek colony, and the derivation of the name remains unknown, but under the Romans the name was Latinized to Byzantium.

In 1555 the German historian Hieronymus Wolf first used the term Byzantine Empire in Corpus Historiæ Byzantinæ, his collection of the era's historical documents. The term became popularized among French scholars in the 17th century with the publication of the Byzantine du Louvre (1648) and Historia Byzantina (1680), but was not widely adopted by art historians until the 19th century, as the distinctive style of Byzantine architecture and art in mosaics, icon painting, frescos, illuminated manuscripts, small scale sculptures and enamel work, was defined.

The Byzantine Empire lasted until 1453 when Constantinople was conquered by the Turkish Ottoman Empire. Byzantine art and architecture is usually divided into three historical periods: the Early Byzantine from c. 330-730, the Middle Byzantine from c. 843-1204, and Late Byzantine from c. 1261-1453. The political, social, and artistic continuity of the Empire was disrupted by the Iconoclastic Controversy from 730-843 and then, again, by the Period of the Latin Occupation from 1204-1261.

The Roman Empire

In the era leading up to the founding of the Byzantine Empire, the Roman Empire was the most powerful economic, political, and cultural force in the world. A polytheistic society, Roman religion was deeply informed by Greek mythology, as Greek gods were adopted into the Roman mos maiorum, or "way of the ancestors," viewing their own founding fathers as the source of their identity and worldly power. At the same time, as the empire absorbed the deities of the peoples they conquered as a way of supporting civic stability, the monotheism of Christianity, which first appeared in Roman-held Judea in the 1st century, was seen as a political and civil threat. The Emperor Nero instituted the first persecution of Christians, as he blamed the sect for the Great Fire of Rome in 65, and subsequent emperors followed suit.

In 303 the Roman Emperor Diocletian instituted the Great Prosecution, during an era when political leaders, including Constantine, were engaged in a war, driven by competing claims to be Diocletian's successor. Facing a battle with his rival Maxentius, legend has it that Constantine converted to Christianity because of a vision. Described by the historian Eusebius, "he saw with his own eyes in the heavens a trophy of the cross arising from the light of the sun, carrying the message, In Hoc Signo Vinces (In this sign, you shall conquer)." Marking his soldier's shields with the Chi Rho, a symbol of Christ, Constantine was victorious and, subsequently, became emperor. His 313 Edict of Milan legalized the practice of Christianity, and in 324, he moved to create a new capital in the East, Constantinople, in order to integrate those provinces into the empire while simultaneously creating a new center of art, culture, and learning.

Early Christian Art

Creating frescoes, mosaics, and panel paintings, Early Christian art drew upon the styles and motifs of Roman art while repurposing them to Christian subjects. Works of art were created primarily in the Christian catacombs of Rome, where early depictions of Christ portrayed him as the classical "Good Shepherd," a young man in classical dress in a pastoral setting. At the same time, meaning was often conveyed by symbols, and an early iconography began to develop. As the Edict of Milan was followed by the Emperor Theophilus I's 380 edict establishing Christianity as the official religion of the empire, Christian churches were built and decorated with frescoes and mosaics. The classical sculptural tradition was abandoned, as it was feared that figures in the round were too reminiscent of pagan idols. In the first two centuries of the Byzantine Empire, as the historians Horst Woldemar Janson and Anthony F. Janson wrote, there was, "No clear-cut line between Early Christian and Byzantine art. East Roman and West Roman - or, as some scholars prefer to call them, Eastern and Western Christian - traits are difficult to separate before the sixth century."

Early Byzantine Art and Emperor Justinian I

The flowering of Byzantine architecture and art occurred in the reign of the Emperor Justinian from 527-565, as he embarked on a building campaign in Constantinople and, subsequently, Ravenna, Italy. His most notable monument was the Hagia Sophia (537), its name meaning "holy wisdom," an immense church with a massive dome and light filled interior. The Hagia Sophia's many windows, colored marble, bright mosaics, and gold highlights became the standard models for subsequent Byzantine architecture.

To design the Hagia Sophia, burnt down in a previous riot, Justinian I employed two well-known mathematicians, Isidore of Miletus and Anthemius of Tralles. Isidore taught stereometry, or solid geometry, and physics and was known for compiling the first collection of the works of Archimedes, a classical Greek engineer and scientist. A mathematician, Anthemius wrote a pioneering study on solid geometric forms and their relationships while arranging surfaces to focus light on a single point. The two men drew upon their knowledge of geometrical principles to engineer the Hagia Sophia's large dome as they pioneered the use of pendentives. The triangular supports at the corners of the dome's square base redistributed the weight, making it possible to build the largest dome in the world until the St. Peter's Basilica dome, which also employed pendentives, was completed in Rome in 1590.

Hiring 10,000 artisans to build and decorate the Hagia Sophia, Justinian I also established innumerable workshops in icon painting, ivory carving, enamel metalwork, mosaics and fresco painting in Constantinople. As art historians H.W. Janson and Anthony F. Janson wrote, during his reign, "Constantinople became the artistic as well as political capital of the empire....The monuments he sponsored have a grandeur that justifies the claim that his era was a golden age." As the Empire was at its most geographically expansive during Justinian's reign, Byzantine art and architecture influenced modern day Turkey, Greece, the Adriatic regions of Italy, the Middle East, Spain, Northern Africa, and Eastern Europe. While other structures, particularly his Chrysotriklinos, the imperial palace reception room, were equally influential, that building, like other early structures in Constantinople, was later destroyed. As a result, the best examples of Early Byzantine innovation can be seen in Ravenna, Italy.

Ravenna, Italy

Justinian I appointed his protégé Maximianus, a lowly and somewhat unpopular deacon, as Archbishop of Ravenna, where he acted as a kind of implicit regent for the Emperor within Italy. In 547, Maximianus completed the construction of San Vitale, a central-plan church using a Greek cross within a square that became a model for subsequent architecture. The shallow dome, placed upon a drum, used terra cotta forms for the first time as construction material, while the interior's exquisite mosaics and sacred objects, including the Throne of Maximianan (mid-11th century) defined the Byzantine style.

Having survived almost intact since its consecration, the interior of the Church of San Vitale created an effect of intricate splendor, with every inch richly decorated. Large mosaics depicting the Emperor and Empress established Byzantine composition and figurative techniques, as the realistic depictions of classical art were abandoned in favor of an emphasis upon iconographic formality. The tall, thin, and motionless figures with almond shaped faces and wide eyes, posed frontally, against a gold background became the instantly recognizable definition of Byzantine art.

Acheiropoieta and Icons

Early Byzantine artists pioneered icon painting, small panels depicting Christ, the Madonna, and other religious figures. Objects of both personal and public veneration, they developed from classical Greek and Roman portrait panels and were informed by the Christian tradition of Acheiropoieta. Acheiropoieta, meaning, "made without hands," was an image believed to have been miraculously created. According to tradition, St. Luke the Evangelist, one of the original twelve apostles, painted the image of the Madonna and Child Jesus when they miraculously appeared to him. The Monastery of the Panaghia Hodegetria in Constantinople was built to house a now-lost icon believed to be St. Luke's painting. As art historian Robin Cormack noted, it became "perhaps the most prominent cult object in Byzantium." These miraculous images influenced the development of iconographic types, as St. Luke's icon became known as Hodegetria, meaning "She Who Points the Way," as the Madonna pointed to the Child Jesus.

Acheiropoieta were often credited with contemporary miracles. The Image of Edessa was believed to have come to the divine aid of the city of Edessa in its 593 defense against the Persians. The central image of Christ's head, known as the Mandylion in the Byzantine tradition, recalled the image of Christ's face imprinted on a cloth while he walked to the place of his crucifixion. Worshippers believed they were in the presence of the divine, as art historian Elena Boerck wrote, "Icons, unlike idols, have their own agency. They're interactive images, in which the divine is present." Nonetheless, as the worship of icons became a dominant feature of Byzantine life, a fierce and destructive theological debate developed.

Iconoclastic Controversy

By the 8th century, the Byzantine Empire was under pressure and often at war, and in this tense climate the controversy over the spiritual validity of icons erupted. Motivated by the belief that recent events, including military defeats and a volcanic eruption in the Aegean Sea in 726, were God's punishment for what he called, "a craft of idolatry," the Emperor Leo III officially prohibited religious images in 730 and launched a movement called Iconoclasm, meaning "breaking of icons." Long standing theological debates over the divine and human nature of Christ and a power struggle between the imperial state and the church stoked the controversy. The Iconoclasts felt that no icon could portray both Christ's divine and human nature, and to convey only one aspect of Christ was a heresy. Those who supported icons argued that, unlike idols which depicted a false god, the images simply depicted the incarnate Christ and that the images derived their authority from Acheiropoieta. By inserting himself into the debate, the Emperor substituted imperial decree for religious authority, undercutting the influence and power of the church. Subsequently, the state violently supressed monastic clergy and destroyed icons.

The era came to an end with a change in imperial power. Following the death of her husband, the Emperor Theophilus, in 842, the Empress Theodora took the throne and, as she was passionately devoted to the veneration of icons, summoned a council that restored icon worship and deposed the iconoclastic clergy. The occasion was celebrated at the Feast of Orthodoxy in 843, and icons were carried in triumphal procession back to the various churches from which they had been taken. Nonetheless, the Iconoclastic Controversy had a notable impact on the later development of art, as the councils that restored the worship of icons also formulated a codified system of symbols and iconographic types that were also followed in mosaics and fresco painting.

Middle Byzantine 867-1204

The Middle Byzantine era is often called the Macedonian Renaissance, as Basil I the Macedonian, crowned in 867, reopened the universities and promoted literature and art, renewing an interest in classical Greek scholarship and aesthetics. Greek was established as the official language of the Empire, and libraries and scholars compiled extensive collections of classical texts. The Ecumenical Patriarch of Constantinople, Photios was not only the leading theologian but has been described by the historian Adrian Forescue as "the greatest scholar of his time." His Bibliotheca was an important compilation of almost three hundred works by classical authors, and he played a leading role in seeing Byzantine culture as rooted in Greek culture. The result was, as Janson and Janson wrote, "an almost antiquarian enthusiasm for the traditions of classical art," displayed in works like the illuminated manuscript, the Paris Psalter (c. 900) a book of Biblical psalms that included full page illustrations from the life of King David and that employed a more realistic treatment of both the figures and the landscape.

Throughout Europe, Byzantine culture and art was seen as the height of aesthetic refinement, and, as a result, many rulers, even those politically antagonistic to the Empire, employed Byzantine artists. In Sicily, which had been conquered by the Normans, Roger II, the first Norman King, recruited Byzantine artists and, as a result, the Norman architecture that developed in Sicily and Great Britain, following the Norman Conquest in 1066, profoundly influenced Gothic architecture. Hundreds of Byzantine artists were also employed at the Basilica of San Marco in Venice when construction began in 1063. In Russia, Vladimir of Kyiv converted to the Orthodox Church upon his marriage to a Byzantine princess. He employed artists from Constantinople at the St. Sophia's Cathedral he built in Kyiv in 1307. Notable examples of Macedonian Renaissance art were also created in Greece, while the influx of Byzantine artists influenced art throughout Western Europe as shown by the Italian artist Berlinghiero of Lucca's Hodegetria (c. 1230).

The Latin Occupation 1204-1261

Famed for its wealth and artistic treasures, Constantinople was cruelly sacked and the Empire conquered in 1204 by the Crusade Army and Venetian forces under the Fourth Crusade. The brutal attack upon a Christian city and its inhabitants was unprecedented, and historians view it as a turning point in medieval history, creating a lasting schism between the Catholic and Orthodox churches, severely weakening the Byzantine Empire and contributing to its later demise when conquered by the Turkish Ottoman Empire. Many notable artworks and sacred objects were looted, destroyed, or lost. Some works, like the Roman bronze works of the Hippodrome, were carried off to Venice where they are still on display, while other works, including sacred objects and altars as well as classical bronze statues, were melted down, and the Library of Constantinople was destroyed. Though the Latins were driven out by 1261, Byzantium never recovered its former glory or power.

Late Byzantium 1261-1453

Following the Latin Conquest, the Late Byzantine era began to renovate and restore Orthodox churches. However, as the Conquest had decimated the economy and left much of the city in ruins, artists employed more economical materials, and miniature mosaic icons became popular. In icon painting, the suffering of the population during the Conquest led to an emphasis upon images of compassion, as shown in sufferings of Christ. Artistic vitality shifted to Russia, Bulgaria, Romania, and Greece, where regional variations of icon painting developed. Russia became a leading center with the Novgorod School of Icon Painting, led by master painters Theophanes the Greek and Andrei Rublev. Byzantine art also influenced contemporaneous art in the West, particularly the Sienese School of Painting and the International Gothic Style, as well as painters like Duccio in his Stroganoff Madonna (1300).

Byzantine Art and Architecture: Concepts, Styles, and Trends

Architectural Innovations

Known for its central plan buildings with domed roofs, Byzantine architecture employed a number of innovations, including the squinch and the pendentive. The squinch used an arch at the corners to transform a square base into an octagonal shape, while the pendentive employed a corner triangular support that curved up into the dome. The original architectural design of many Byzantine churches was a Greek cross, having four arms of equal length, placed within a square. Later, peripheral structures, like a side chapel or second narthex, were added to the more traditional church footprint. In the 11th century, the quincunx building design, which used the four corners and a fifth element elevated above it, became prominent as seen in The Holy Apostles in Thessaloniki, Athens, Greece. In addition to the central dome, Byzantine churches began adding smaller domes around it.

Poikilia

Byzantine architecture was informed by Poikilia, a Greek term, meaning "marked with various colors," or "variegated," that in Greek aesthetic philosophy was developed to suggest how a complex and various assemblage of elements created a polysensory experience. Byzantine interiors, and the placement of objects and elements within an interior, were designed to create ever changing and animated interior as light revealed the variations in surfaces and colors. Variegated elements were also achieved by other techniques such as the employment of bands or areas of gold and elaborately carved stone surfaces.

For instance the basket capitals in the Hagia Sophia were so intricately carved, the stone seemed to dematerialize in light and shadow. Decorative bands replaced moldings and cornices, in effect rounding the interior angles so that images seemed to flow from one surface to another. Photios described this surface effect in one of his homilies: "It is as if one had entered heaven itself with no one barring the way from any side, and was illuminated by the beauty in changing forms...shining all around like so many stars, so is one utterly amazed. [...] It seems that everything is in ecstatic motion, and the church itself is circling around."

Iconographic Types and Iconostasis

Byzantine art developed iconographic types that were employed in icons, mosaics, and frescoes and influenced Western depictions of sacred subjects. The early Pantocrator, meaning "all-powerful," portrayed Christ in majesty, his right hand raised in a gesture of instruction and led to the development of the Deësis, meaning "prayer," showing Christ as Pantocrator with St. John the Baptist and the Virgin Mary, and, sometimes, additional saints, on either side of him. The Hodegetria developed into the later iconographic types of the Eleusa, meaning tenderness, which showed the Madonna and the Child Jesus in a moment of affectionate tenderness, and the Pelagonitissa, or playing child, icon. Other iconographic types included the Man of Sorrows, which focused on depicting Christ's suffering, and the Anastasis, which showed Christ rescuing Adam and Eve from hell. These types became widely influential and were employed in Western art as well, though some like the Anastasis only depicted in the Byzantine Orthodox tradition.

Iconostasis, meaning "altar stand," was a term used to refer to a wall composed of icons that separated worshippers from the altar. In the Middle Byzantine period, the Iconostasis evolved from the Early Byzantine templon, a metal screen that sometimes was hung with icons, to a wooden wall composed of panels of icons. Containing three doors that had a hierarchal purpose, reserved for deacons or church notables, the wall extended from floor to ceiling, though leaving a space at the top so that worshippers could hear the liturgy around the altar. Some of the most noted Iconostases were developed in the Late Byzantine period in the Slavic countries, as shown in Theophanes the Greek's Iconostasis (1405) in the Cathedral of the Annunciation in Moscow. A codified system governed the placement of the icons arranged according to their religious importance.

Novgorod School of Icon Painting

The Novgorod School of Icon Painting, founded by the Byzantine artist, Theophanes the Greek, became the leading school of the Late Byzantine era, its influence lasting beyond the fall of the Byzantine Empire in 1453. Theophanes' work was known for its dynamic vigor due to his brushwork and his inclusion of more dramatic scenes in icons, which were usually only depicted in large-scale works. He is believed to have taught Andrei Rublev who became the most renowned icon painter of the era, famous for his ability to convey complex religious thought and feeling in subtly colored and emotionally evocative scenes. In the next generation, the leading icon painter Dionysius experimented with balance between horizontal and vertical lines to create a more dramatic effect. Influenced by Early Renaissance Italian artists who had arrived in Moscow, his style, known for pure color and elongated figures, is sometimes referred to as "Muscovite mannerism," as seen in his icon series for the Cathedral of the Dormition (1481) in Moscow.

Carved Ivory

In the Byzantine era, the sculptural tradition of Rome and Greece was essentially abandoned, as the Byzantine church felt that sculpture in the round would evoke pagan idols; however, Byzantine artists pioneered relief sculpture in ivory, usually presented in small portable objects and common objects. An early example is the Throne of Maximianan (also called, the Throne of Maximianus), made in Constantinople for the Archbishop Maximianus of Ravenna for the dedication of San Vitale. The work depicted Biblical stories and figures, surrounded by decorative panels, carved in different depths so that the almost three-dimensional treatment in some panels contrasted against the more shallow two-dimensional treatment of others.

In the Middle Byzantine period, ivory carving was known for its elegant and delicate detail, as seen in the Harbaville Triptych (mid-11th century). Reflecting the Macedonian Renaissance's renewed interest in classical art, artists depicted figures with more naturally flowing draperies and contrapposto poses. Byzantine ivory carvings were highly valued in the West, and, as, a result, the works exerted an artistic influence. The Italian artist Cimabue's Madonna Enthroned (1280-90), a work prefiguring the Italian Early Renaissance's use of depth and space, is predominantly informed by Byzantine conventions.

Later Developments - After Byzantine Art and Architecture

During its almost one thousand year span, the Byzantine era influenced Islamic architecture, the art and architecture of the Carolingian Renaissance, Norman architecture, Gothic architecture, and the International Gothic style. When the Turkish Ottoman Empire conquered Constantinople in 1453, renaming it Istanbul, the Byzantine Empire came to an end. Nonetheless the Byzantine style continued to be employed in Greece and in Eastern Europe and Russia, where a "Russo-Byzantine" style developed in architecture.

In the mid-1800s, Russia underwent a Byzantine Revival, also called the Neo-Byzantine, which was established as the official style for churches by Alexander II of Russia, who reigned from 1885-1891. The style continued to be used until World War I, and, following the Russian Revolution of 1917, a number of architects immigrated to the Balkans where churches in the Byzantine Revival style continued to be made until after World War II. The veneration of icons, and the painting of them, is still a notable feature of the Orthodox faith, as Orthodox households have a space dedicated to icons, and churches, renowned for their images, draw worshippers from near and far.

Byzantine icons have continued to exert an influence, being employed for more traditional religious imagery, such as Luigi Crosio's late 19th-century rendering of Lady of Refuge, a popular image among Catholics, but also reframed within modern art in works such as Natalia Goncharova's The Evangelists (1911) and other Russian Futurists of the time. In particular, Russian Suprematist painter Kazimir Malevich famously exhibited his radically abstract Black Square (1915) in the corner of the room, a space traditionally reserved for religious icons and referred to as the "red corner." As Russian writer Tatyana Tolstaya wrote of this radical act, "Instead of red, black (zero color); instead of a face, a hollow recess (zero lines); instead of an icon - that is, instead of a window into the heavens, into the light, into eternal life - gloom, a cellar, a trapdoor into the underworld, eternal darkness." In subverting the traditional Byzantine icon, Malevich hoped to comment on the bleak state of modernity.

Contemporary Interpretations of the Style

Contemporary artists working in Byzantine styles and subjects include the Russian Maxim Sheshukov, the Romanian Ioan Pope, the American architect Andrew Gould, iconographer Peter Pearson, the Canadian sculptor Jonathan Pageau, and the Ukrainian Angelika Artemenko. The Archimandrite, or priest-monk, Zenon Theodor was acclaimed for his 2008 paintings in St. Nicholas Cathedral, in Vienna, Austria, while Greek artist Fikos combines Byzantine murals and icons with his interest in street art, comic book strips, and graffiti in what he calls "Contemporary Byzantine Painting." In America, the Brooklyn-based Alfonse Borysewicz has been called "one of the most important religious artists since the French Catholic Georges Rouault" by art historian Gregory Wolfe.

Ask The Art Story AI

Ask The Art Story AI