Summary of De Stijl

The Netherlands-based De Stijl movement embraced an abstract, pared-down aesthetic centered in basic visual elements such as geometric forms and primary colors. Partly a reaction against the decorative excesses of Art Deco, the reduced quality of De Stijl art was envisioned by its creators as a universal visual language appropriate to the modern era, a time of a new, spiritualized world order. Led by the painters Theo van Doesburg and Piet Mondrian - its central and celebrated figures - De Stijl artists applied their style to a host of media in the fine and applied arts and beyond. Promoting their innovative ideas in their journal of the same name, the members envisioned nothing less than the ideal fusion of form and function, thereby making De Stijl in effect the ultimate style. To this end, De Stijl artists turned their attention not only to fine art media such as painting and sculpture, but virtually all other art forms as well, including industrial design, typography, even literature and music. De Stijl's influence was perhaps felt most noticeably in the realm of architecture, helping give rise to the International Style of the 1920s and 1930s.

Key Ideas & Accomplishments

- Like other avant-garde movements of the time, De Stijl, which means simply "the style" in Dutch, emerged largely in response to the horrors of World War I and the wish to remake society in its aftermath. Viewing art as a means of social and spiritual redemption, the members of De Stijl embraced a utopian vision of art and its transformative potential.

- Among the pioneering exponents of abstract art, De Stijl artists espoused a visual language consisting of precisely rendered geometric forms - usually straight lines, squares, and rectangles--and primary colors. Expressing the artists' search "for the universal, as the individual was losing its significance," this austere language was meant to reveal the laws governing the harmony of the world.

- Even though De Stijl artists created work embodying the movement's utopian vision, their realization that this vision was unattainable in the real world essentially brought about the group's demise. Ultimately, De Stijl's continuing fame is largely the result of the enduring achievement of its best-known member and true modern master, Piet Mondrian.

Overview of De Stijl

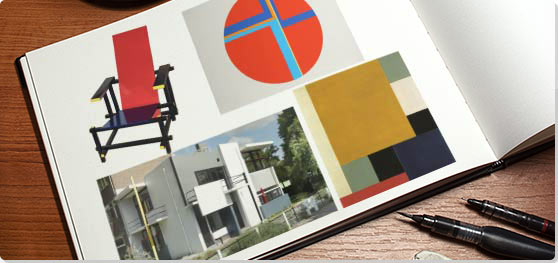

Gerrit Rietveld said, "We must remember that sit is a verb too." In 1918 he had a poem incised on the underside of his Red and Blue Chair that read, "When I sit, I do not want to sit as my seated flesh likes, but rather as my seated spirit would sit, if it wove the chair for itself." The work and the philosophy it expressed became canonical to de Stijl.

Artworks and Artists of De Stijl

Composition A

Composition A - whose title announces its nonobjective nature by making no reference to anything beyond itself - is a good example of Mondrian's geometric abstraction before it fully matured within the framework of the De Stijl aesthetic. With its rectilinear forms made up of solid, outlined areas of color, the work reflects the artist's experimentation with Schoenmaekers's mathematical theory and his search for a pared-down visual language appropriate to the modern era. While here Mondrian uses blacks and shades of grey, his paintings would later be further reduced, ultimately employing more basic compositions and only solid blocks of primary colors.

Oil on canvas - Galleria Nazionale d'Arte Moderna, Rome

Mechano-Dancer

This early work employs the signature geometric shapes of the De Stijl aesthetic, yet its layering of shapes and forms, and combination of horizontal, vertical, and diagonal lines--along with the absence of color - reflect a different approach from that of the movement's leading artists, van Doesburg and Mondrian. The work's suggestion of a human figure - accomplished by the arrangement of geometric forms and placement of a cube at the top, possibly representing a head - is also unique in De Stijl art. Mechano-Dancer's evocation of a hybrid man-machine, also implied by its title, suggests the influence of Dada and Italian Futurism.

Photomontage - Private Collection, New York

Red and Blue Chair

Originally designed in 1918 but not fully realized until 1923, when it incorporated the characteristic De Stijl scheme of primary colors, Red and Blue Chair is one of the canonical works of the movement. Rietveld envisioned a chair that played with and transformed the space around it, consisting of rectilinear volumes, planes, and lines that interact in unique ways, yet manage to avoid intersection. Every color, line, and plane is clearly defined, as if each comprised its own work that just happened to be used for a piece of furniture. The simple assembly Rietveld deployed was quite intentional as well; he built the chair out of standard lumber sizes available at the time, reflecting his goal of realizing a piece of furniture that could be mass-produced as opposed to hand-crafted. Emphasizing its manmade quality, Red and Blue Chair also notably avoids the use of natural form, which furniture designers tend to favor in order to emphasize the idea of physical comfort and convenience.

Painted wood - Auckland Museum, New Zealand

Counter Composition V

First introduced in 1924, van Doesburg's Counter Compositions - his signature works - embody the artist's wish to move beyond the confines of De Stijl with his introduction of Elementarism. While van Doesburg continued to make use of horizontal and vertical lines, he now prioritized the diagonal line; he described Elementarism as "based on the neutralization of positive and negative directions by the diagonal and, as far as color is concerned, by the dissonant. Equilibrated relations are not an ultimate result." The titles of his Counter Compositions refer to the fact that the lines of the compositions are at a 45-degree angle to the sides of the picture rather than parallel to them, resulting in a newly energized relationship between the composition and format of the canvas. As in the present example, he repeatedly ventured beyond the three primary colors, including a triangle of grey in addition to the primary colors, white, and black. At the time he painted this composition, De Stijl was finding its own unique voice; paintings, furniture designs, and buildings produced by those associated with the movement communicated how lines and colors should interact, and how a work's appearance is just as essential as its function.

Oil on canvas - Stedelijk Museum, Amsterdam

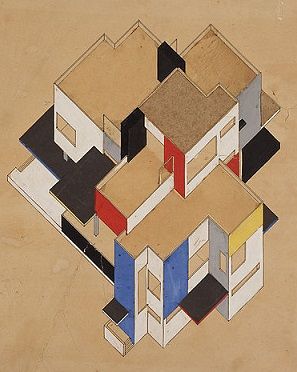

Rietveld Schröder House

The Rietveld Schröder House is an important precursor to the Bauhaus-inspired International Style, as well as the only building designed in complete accordance with the De Stijl aesthetic. The house was commissioned in 1924 by Truus Schröder-Schrader, who intended for the new home to be grand and open ("without walls"), a veritable manifesto for how an independent modern woman should live her life. Featuring the typical De Stijl palette of primary colors, black, and white, the building emphasizes its architectural elements - slabs, posts, and beams - reflecting the movement's emphasis on form, construction, and function in its architecture and design. In other ways, too, the design represents a major departure from architectural convention and precedent. Inside, the rooms are constructed as movable entities with portable walls. In addition, Rietveld's design makes no attempt to interact with any of the surrounding buildings or roadways, suggesting its presence as an isolated structure focusing inward instead of outward.

Concrete, brick, and plaster, wood, steel girders - Utrecht, The Netherlands

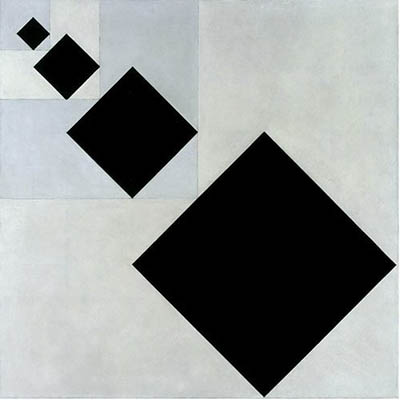

Arithmetic Composition

Made close to the end of van Doesburg's life, Arithmetic Composition reflects the artist's experimentation with abstract geometric shapes within a diagonal composition, resulting in a dimensional plane that would not have the same visual effect had the blocks been positioned vertically or horizontally. The work's diagonal configuration, combination of pure positive and negative space (black forms against white background), and incorporation of a curious backward "L" in the upper left corner, which consumes one block, create a sense of movement, making the shapes appear as if they are alternately moving toward and away from the viewer. However, unlike Mondrian's characteristic vertical-and-horizontal paintings, which lend themselves to the suggestion of figuration, van Doesburg here creates an abstract artwork totally devoid of the possibility of representation.

Oil on canvas - Kunstmuseum Winterthur, Switzerland

Beginnings of De Stijl

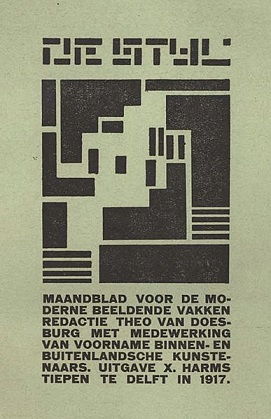

In 1917, Theo van Doesburg founded the contemporary art journal De Stijl as a means of recruiting like-minded artists in the formation of a new artistic collective that embraced an expansive notion of art, infused by utopian ideals of spiritual harmony. The journal provided the basis of the De Stijl movement, a Dutch group of artists and architects whose other leading members included Piet Mondrian, J. J. P. Oud and Vilmos Huszar.

Adopting the visual elements of Cubism and Suprematism, the anti-sentimentalism of Dada, and the Neo-Platonic mathematical theory of M. H. J Schoenmaekers, a mystical ideology that articulated the concept of "ideal" geometric forms, the exponents of De Stijl aspired to be far more than mere visual artists. At its core, De Stijl was designed to encompass a variety of artistic influences and media, its goal being the development of a new aesthetic that would be practiced not only in the fine and applied arts, but would also reverberate in a host of other art forms as well, among them architecture, urban planning, industrial design, typography, music, and poetry. The De Stijl aesthetic and vision was formulated in large response to the unprecedented devastation of World War I, with the movement's members seeking a means of expressing a sense of order and harmony in the new society that was to emerge in the wake of the war.

De Stijl: Concepts, Styles, and Trends

Pure Geometric Abstraction and De Stijl Visual Language

De Stijl was the first-ever journal devoted to abstraction in art, although the movement's artists were not the first to practice abstract art; other painters, perhaps most notably Wassily Kandinsky, Kazimir Malevich and Hans Arp, had earlier created nonobjective art, often incorporating geometric forms in their work. But the artists and architects associated with De Stijl - painters such as Mondrian, van Doesburg and Ilya Bolotowsky, and architects such as Gerrit Rietveld and J. J. P. Oud - adopted what they perceived to be a purer form of geometry, consisting of forms made up of straight lines and basic geometric shapes (largely rendered in the three primary colors); these motifs provided the fundamental elements of compositions that avoided symmetry and strove for a balanced relationship between surfaces and the distribution of colors. In Neo-Plasticism in Pictorial Art, Mondrian explained: "As a pure representation of the human mind, art will express itself in an aesthetically purified, that is to say, abstract form. The new plastic idea cannot, therefore, take the form of a natural or concrete representation."

Neo-Plasticism

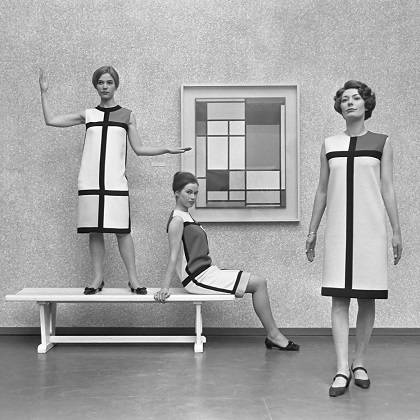

Neo-Plasticism refers to the painting style and ideas developed by Piet Mondrian in 1917, promoted by De Stijl. Denoting the "new plastic art," or simply "new art," the term embodies Mondrian's vision of an ideal, abstract art form he felt was suited to the modern era. Mondrian's essay Neo-Plasticism in Pictorial Art, which set forth the principles of the concept, was published in twelve installments of the journal De Stijl in 1917-18. Mondrian described Neo-Plasticism as a reductive approach to artmaking that stripped away traditional elements of art, such as perspective and representation, utilizing only a series of primary colors and straight lines. Mondrian envisioned that the principles of Neo-Plasticism would be transplanted from the medium of painting to other art forms, including architecture and design, providing the basis of the transformation of the human environment sought by De Stijl artists. In Mondrian's words, a "pure plastic vision should build a new society, in the same way that in art it has built a new plasticism."

The concept of Neo-Plasticism was largely inspired by M. H. J. Schoenmaekers's treatise Beginselen der Beeldende Wiskunde (The Principles of Plastic Mathematics), which proposed that reality is composed of a series of opposing forces - among them the formal polarity of horizontal and vertical axes and the juxtaposition of primary colors.

Neo-Plasticism was later promoted by the movement Cercle et Carre and three issues of its eponymous journal appearing in 1930. Following Mondrian's visit to the U.S. in 1940, the style spread to the U.S., where it was taken up by various American abstract artists.

Elementarism

While only horizontal and vertical lines were to be utilized in Neo-Plasticism, in 1925, van Doesburg developed Elementarism, which attempted to modify the dogmatic nature of the style by introducing the diagonal, a form that for him connoted dynamism - "a state of continuous development." In "Painting and Sculpture: Elementarism (Fragment of a Manifesto)," published in De Stijl in 1927, he wrote: "If all our physical movements are already based upon Horizontal and Vertical, it is only an emphasis of our physical nature, of the natural structure and functions of organisms if the work of art strengthens - although in an 'artistic manner' - this natural duality in our consciousness."

Prizing horizontal and vertical lines for their connotation of stability, Mondrian strongly disagreed with van Doesburg's newfound emphasis on the diagonal--a disagreement that famously prompted Mondrian to secede from De Stijl shortly thereafter. For Mondrian, van Doesburg's introduction of the diagonal amounted to artistic heresy; in Mondrian's view, the Elementarist diagonal repudiated De Stijl's efforts to fully integrate all the elements of the painting by creating tension between the composition and the picture plane.

Later Developments - After De Stijl

De Stijl-inspired architecture, particularly by Rietveld and Oud, was built in the Netherlands throughout the 1920s, all of which, interestingly enough, seemed to defy van Doesburg's theory of Elementarism, instead utilizing clearly defined horizontal and vertical lines. De Stijl also had a major influence on Bauhaus architecture and design; several members of De Stijl taught at the Bauhaus, perhaps most importantly van Doesburg, who lectured there in 1921-22. De Stijl's geometric visual language, along with its architectural concepts such as form following function and the emphasis on structural components, would reverberate in Bauhaus architectural practice, as well as the global idiom known as the "International Style."

With Theo van Doesburg's death in 1931, De Stijl lost its leader, and soon after faded from existence. However, the movement's key ideas of pure geometric abstraction and the relationship of form and function were maintained by many following van Doesburg's death, and represent a fundamental contribution to modern and contemporary art, design, and architecture. Many of Rietveld's buildings, for example, survive the longevity of the De Stijl movement, and inspired a great many 20th-century architects, among them Mies van der Rohe.

Beyond the realm of architecture, the pared-down De Stijl aesthetic influenced many subsequent artists and designers of the 20th century and beyond, among them the Abstract Expressionists Mark Rothko and Barnett Newman, Hard-edge painters Frank Stella and Frederick Hammersley, and Minimalists Donald Judd and Dan Flavin.

Useful Resources on De Stijl

- The Story of De StijlOur PickBy Hans Janssen, Michael White

- de StijlBy Paul Overy

- De Stijl and Dutch ModernismOur PickBy Michael White

- Towards Universality: Le Corbusier, Mies and De StijlBy Richard Padovan

- Principes fondamentaux de l'art néo-plastique (French Edition)By Theo van Doesburg

- Piet Mondrian: Catalogue Raisonné (Vol 1)Our PickBy Paul Overy

- The Ideal as Art: de Stijl, 1917-1931Our PickBy Carsten-Peter Warncke

- Van Doesburg & the International Avant-Garde: Constructing a New WorldOur PickBy Gladys Fabre, Doris Wintgens Hotte, Michael White

- Mondrian De StijlHans Janssen, Franz-W. Kaiser, Matthias Muhling, Piet Mondrian

- Gerrit Rietveld Compl. WorksBy M. Kuper, I. Van Zijl

Ask The Art Story AI

Ask The Art Story AI