Summary of Group f/64

Formed in the San Francisco Bay Area, the 11 members of Group f/64 (sometimes referred to as the West Coast Photographic Movement) owed their assiduous aesthetic precision in fact to the East Coast of America and to the endeavors of Paul Strand. It was Strand who can claim to have developed and finessed Straight Photography and it was indeed the pursuit of a "pure" (or Straight) image that became Group f/64's unifying quest.

One of the most famous photographic collectives in history, Group f/64 mounted a revolt against the dominant fashion within the art of photography which was to ape the painterly and graphic techniques associated with Bay Area Pictorialism. The members' preference was for a style of art photography that would fully promote the camera's unique mechanical qualities. As the Group declared in its 1932 manifesto: "Pure photography is defined as possessing no qualities of technique, composition or idea, derivative of any other art form [and] The Group will show no work at any time that does not conform to its standards." Indeed, the diaphragm number f/64 from which the Group took its name, is the smallest camera lens aperture possible and thereby lends the image a sharpness and detail in depth that simply could not be replicated by the hand or in real time. The Group used large format view cameras to achieve their effect and they produced images ranging in theme through landscapes, still lifes, nudes, and architectural features.

Key Ideas & Accomplishments

- Typically, Straight Photography used large format cameras to create high contrast semi-abstractions and/or geometric repetitions. The images were often reliant on size and context for their full aesthetic affect and these imagess were thus intended to be exhibited in dedicated galleries before they passed into print publication.

- Group f/64 as a whole was committed to photographing ignored or mundane objects to which they brought new perspectives and meaning through their pursuit of the purest image. In short, the spectator was often invited to "take a second look" at what they might have otherwise taken for granted. It was the goal of elevating the world around them to something more "spiritual" that saw them ranked as high-modernists.

- During its short existence, the members of Group f/64 remained faithful to the ontology of the photographic image. In other words, their images existed on their own terms and were thus devoid of any social or political reference. Though this approach invited criticism from some quarters, the Group was committed to the principle that photography - or rather pure photography - must be left to stand alone if it was to affect supreme mental attainment in the spectator.

- While it was not uncommon for modernists to strive for activity and movement in their photographic images, Group f/64's approach to its subjects was studied and measured. There is then a stillness and serenity to be found in the Group's compositions. This tranquillity gave the images - especially so when viewed in the surroundings of the gallery - an aura that was unique to pure photography.

Important Photographs and Artists of Group f/64

Mills College Amphitheater

In 1920 after moving to San Francisco, Cunningham's photography turned away from Pictorialism toward sharply focused images of her subjects that included nudes, portraits, botanical still lifes, architecture, and industrial buildings. Already well known, particularly due to her pioneering images of the male nude (which created some controversy and scandal) Cunningham was an early innovator of the aesthetic approach that later became synonymous with Group f/64.

This photograph's partial view of the empty amphitheater emphasizes the pattern of the rows that, beginning at the lower right, curve through the pictorial plane to the upper right. A dynamic energy is created by the intersecting diagonals of three stone stairways, descending to the half circle of the stage, as their smaller rectangular forms interplay with the sharply contrasted light and shadow of the curving rows. The arcs of black shadow accentuate the repetition while the sharp focus makes the rough surface of the sunlit stone palpable. The elemental pattern of geometric form makes the space itself the subject, its aesthetic evoking a gathering of energy and attention.

Gelatin silver print - International Center of Photography, New York City

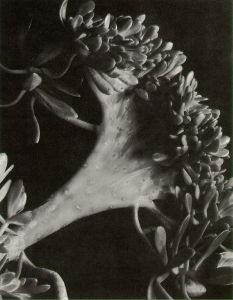

Magnolia Blossom

This photograph is a sharply focused close-up image of a magnolia blossom, as the curving forms of its white petals create a sensuous contrast with the erect pistil and stamen at the center of the image. As art critic Alison Meier noted, such photographs "are like proto-Georgia O'Keeffe flower canvases: clinical yet loving, often surreptitiously sexy - and sometimes not so surreptitious." The play of light and shadow accentuates the softly flaring curvilinear form, while also creating a sense of enveloping depth, as the curving shapes extend beyond the pictorial frame, and draw the viewer into the image. The use of sharp focus lends the "masterwork," as New York Times art critic Margaret Loke put it, a "crystalline eroticism."

Cunningham became interested in botany and photography while she was studying chemistry at the University of Washington, when she doubled as a photographer in the botany department. Her thesis "Modern Processes in Photography" (submitted in 1907) combined the two interests. While her early works were influenced by the Pictorialist Gertrude Käsebier, by the early 1920s Cunningham had turned to sharp focus close-ups that exemplified Straight Photography's leanings towards abstraction. Edward Weston, who curated the American contribution to the 1929 Film and Foto exhibition in Germany, included ten of Cunningham's plant photographs. The detail in her images is so precise that many botanists and horticulturists have used them in their studies, and her botanical interest led her to create the California Horticultural Society in 1933. Throughout her long career, Cunningham was noted as a radical thinker and gained renown as an innovator in experimenting photographic techniques and styles.

Gelatin silver print - M.H. de Young Memorial Museum, San Francisco

[Nude]

This close-up of a nude woman, lying on her stomach, is cropped above the shoulders and just below the hips. It is an anonymous figure study designed to emphasize aesthetic form over eroticism. The eloquent curves of the model's back radiate a kind of light, accentuated against the dark neutral background. Art historian Nancy Newhall noted that much "like a chisel" the "luminous flesh rounds out of the shadow, and the shadow itself [...] is as active and potent as the light." The image can be viewed as an abstraction, though the work remains figurative because it is rendered by the objective medium of photography itself.

Weston first began photographing nudes of his various lovers in the early 1920s, and his approach to other subjects, whether landscape or small objects like sea shells, peppers (and even a head of cabbage) are informed by a similar preoccupation with sensuous form. Here the radiant light on the model's back resembles the glow of light along the horizon, with the result that the body evokes what New York Times critic Hilton Kramer called "a landscape of the body."

Weston's work, be it landscape, still lifes or the nude, exemplified the Group f/64 aesthetic. Art historian Lisa Hostetler noted that "While at first glance, these subjects seem to have nothing in common [...] The photographers' meticulous concern for transcribing the exact features of what was before the camera bound them together and rendered the emotional experience of form the primary feature of their photographic art."

Gelatin silver print - The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York City

Monolith, the Face of Half Dome, Yosemite National Park

Adams moved away from his earlier Pictorial landscapes following his discovery of Paul Strand and his Straight aesthetic. Yet, at the same time, Adams's sublime landscapes maintained deeper roots in the idea of American Transcendentalism and the Pictorialist Hudson River School. His initial contribution to Group f/64 came therefore through his elevation of the Western landscape as credible modern (rather than romantic) subject matter. His work not only influenced subsequent photographers (including Minor White and Harry Callahan) but affected a profound impact on growing environmental and wilderness movements, as the continuing popularity of his widely reproduced images instilled a wonder for America's National Parks in the general public.

A dark and brooding image of the Half Dome in Yosemite National Park, Monolith is a high contrast black and white photograph in sharp and deep focus (from foreground to background) taken from a vantage point known as the Diving Board, a granite slab that hangs 3,500 feet above the valley floor. Adams had been searching for a view of the Half Dome that also conveyed his sense of wonder at the natural world. By the time he reached the Diving Board, Adams had only two glass plate negatives left in his satchel. The first of the two was exposed with a yellow filter that he knew would darken the sky slightly. With the second, Adams used a dark red filter that significantly darkened the sky and subsequently emphasized the white snow and gleaming granite of the half dome. The resulting photograph marked a turning point in Adams's work: he had effectively previsualized what the photograph would look like before he pressed down on the shutter. Adams said at the time: "this photograph represents my first conscious visualization; in my mind's eye I saw (with reasonable completeness) the final image as made." In the years that followed, Adams would refine his ideas about previsualization in what he later called the "Zone System."

Silver gelatin print - The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York City

Pepper No. 30

This iconic still life (disliked by Adams) of a somewhat irregularly formed green pepper has come to exemplify Weston's work. The photographer Sonya Noskowiak, who was at that time Weston's lover, offered him some peppers from which he selected this slightly overripe specimen. With its pencil sharp focus, rich tonalities and three-dimensional sculptural form, the pepper was, in the words of art critic Sean O'Hagan, transformed "into a sensual object with curves that echo both modernist sculpture and the human form," while the image's "ultra-realism shades into surrealism."

In preparation for this photograph, Weston spent four days experimenting with lighting and backdrops. He took over thirty photographs before hitting on the idea of placing the pepper inside a tin funnel. Weston described the funnel as the "perfect relief [...] adding reflecting light to important contours."

Weston's knack for transforming everyday objects, be they organic or manmade, was an important impetus in developing Group f/64's aesthetic. Weston explained how the pepper was "abstract in that it [was] completely outside subject matter" and that, moreover, one sees the potential for such a striking image through "through one's intuitive self [by] seeing 'through' one's eyes, not with them." As art critic Goldberg noted, Weston's work "seems to express a semi-religious sense, possibly unarticulated but running through modernism, that the created world, both organic and inorganic, is one, and that formal resemblances are a visual and metaphoric way of affirming this."

Silver gelatin contact print - San Francisco Museum of Modern Art

Bedpan

This photograph of a bedpan emphasizes the white curving object as, standing upright, outlined against a black background, it takes on a kind of monumental dignity. The image's tonalities emphasize the form itself, as intense white accentuates the flaring curves, while a black vertical line dividing the object draws the eye upward to the curving profile of the neck. The overall effect is that any recognition of the pedestrian object is superseded by aesthetic form. As art critic Sean O'Hagan observed, "the tonal quality of his black-and-white prints imbue everyday objects, both natural and man-made, with a heightened presence that sometimes makes them seem almost unreal." As Weston noted in his Daybook, it "might easily be called 'The Princess' or 'The Bird'!" naming two of Constantin Brancusi's noted sculptures. In this sense, Bedpan can be viewed as a companion piece for Pepper No. 30.

In the 1920s Weston took the architect Louis Sullivan's famous declaration "form follows function" as his own motto and said of this bedpan indeed that "It has a stately, aloof dignity," and when "stood on end," it fully evoked the "form follows function" credo. At the same time, the image rather recalled the surrealistic photography of Man Ray and László Moholy-Nagy, and Marcel Duchamp's Dadaist "readymade" Fountain (1917). Weston's choice of such a utilitarian, and somewhat distasteful, object to create something of pure (or Straight) aesthetic value was ground-breaking in the sense that it abandoned both the documentary aspect of photography but also any reference to the traditions of Pictorialism.

Gelatin silver print - The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York City

Bone and Sky

Van Dyke's image depicts a cow's pelvic bone boldly profiled against the sky giving it the status of an elemental and monumental shape. Bold contrasts between light and shadow, accentuated by the sharp focus conveying the bone's rough and broken textures, emphasize the formal qualities of the subject while conveying the effects of searing sunlight. Similarly, the neutral but saturated background evokes both a sense of indeterminate space and the intensity of a cloudless Western sky. The bone's right irregular half, rendered in deep black tonalities against the almost white highlighted left side, creates an abstract form that, emphasized by the circular opening in the upper center, suspends recognition. The shape both lends itself to and resists reading as a stylized mask, a weapon or a modernist sculpture.

With his contribution in cofounding the movement, and in the writing of its manifesto, Van Dyke brought his concept of "pure photography" to Group f/64 in images, like this, that exemplified what he termed a "hard brilliance." Van Dyke also saw the movement as almost organically necessitated by its West Coast location and the "marvellous Californian light." As he said of making this image, "the skies were so blue and the air so crisp and clean and there was a kind of hard brilliance that [was] accentuated by using very sharp lenses and very small apertures." Van Dyke abandoned his commitment to still photography altogether when he moved to New York City in 1935 to pursue a career in documentary filmmaking.

Gelatin silver print - San Francisco Museum of Modern Art, San Francisco

Rose and Driftwood, San Francisco, California

Though his fame is founded on his iconic American landscapes, Adams also produced a small number of still life studies. Like his landscapes, Adams brought a modern sensibility to what was a traditional painterly genre. Without distorting the objects in front of his lens (as was, say, Weston's preference), Adams used sharp focus to emphasize primary elements and relations between objects that might have ordinarily gone unnoticed. In this sense he demonstrated how the photographer could invite the spectator to consider the beauty of everyday things by using the camera to remove, or "liberate", the objects from their original setting.

In Rose and Driftwood, Adams made use of sharp focus and high contrast to depict the delicate veins of the rose and the raised striations of the driftwood. The resulting image is a strikingly modern interpretation of the traditional still life. Unlike Weston, who preferred to isolate objects by physically removing them from their surroundings, Adams married the rose with the wood on which it was placed. Drawing on his experience of photographing landscapes - imparting on him an eye for texture, contrast, composition, and an emotional connection with his choice of subject matter - Adams treats the rose and driftwood in much the same way, using the concentric circles of the driftwood and the rose rising from its surface like elements found in nature.

The Art Institute of Chicago

Beginnings of Group f/64

Before Straight Photography, the idea of a photographic art was associated with Pictorialism, a movement that began in 1885 and dominated international photography for roughly 20 years. Pictorialism emphasized artistic effects by staging subjects, using soft and blurred focus, extensive darkroom manipulations and composite, or merged, photography. However, as early as 1904 the art and photography critic Sadakichi Hartmann was calling on photographers to produce "photographs that look like photographs" (rather than copy pictorial painterly traditions). Hartmann's ideas resonated with the likes of Alfred Stieglitz who was simultaneously an advocate of American Pictorialism and European modern painting. Indeed, Stieglitz's magazine Camera Work, and his famous 291 Gallery in New York, often placed Pictorial and experimental works side by side. By 1915, however, Stieglitz had started to campaign solely on behalf of a pure photography: "Not a trace of hand work on either negative or prints. No diffused focus. Just the straight goods" he declared. That same year, Stieglitz, acting as something of a mentor, dismissed the soft-focus inclinations in Paul Strand's photography. Strand took Stieglitz's rebuke to heart and began working towards what he initially called "objective photographs."

When talking specifically about Straight Photography, it is probably fair to say that, with regard to the Stieglitz and Strand relationship, the pupil had surpassed his master. Strand drew inspiration from the formalist and Cubist paintings of Cézanne, Braque and Picasso, becoming somewhat fixated on the idea that the photographic plane could, like the Cubist canvas, be broken down compositionally into geometric shapes. Strand's early abstract series, published in Camera Works in 1917, merely confirmed him as the leader of the new movement of Straight Photography. However, by the time Group f/64 was formed, Strand had moved towards documentary photography and socio-realism which he blended with his inclination for abstraction. Members of Group f/64 were not bound by overtly political ideals, stating in their manifesto that the Group believed in "photography, as an art form" and as such it "must develop along lines defined by the actualities and limitations of the photographic medium." Indeed, the Group declared that Straight Photography "must always remain independent of ideological conventions of art and aesthetics that are reminiscent of a period and culture antedating the growth of the medium itself."

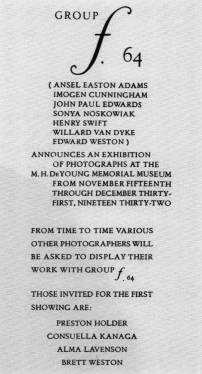

By the 1920s Pictorialism had declined on the East Coast and in Europe but remained popular in other regions of the United States, including on the West Coast and in the Bay Area. The tide was turning however, and in the winter of 1932 eleven (Straight) West Coast photographers gathered at San Francisco's M. H. de Young Memorial Museum for an announcement. Strongly supported by Lloyd Rollins, the museum's new director, the collective announced the formation of their ensemble. The Group was made up of: Ansel Adams, Imogen Cunningham, John Paul Edwards, Preston Holder, Consuelo Kanaga, Alma Lavenson, Sonya Noskowiak, Henry Swift, Willard Van Dyke, Brett Weston and Edward Weston (Bret's father).

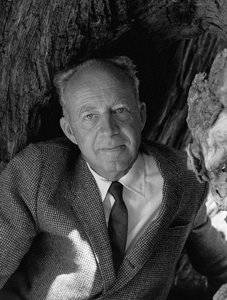

Willard Van Dyke and 683

Though an artistic collective, Willard Van Dyke played a leading role as spokesperson for Group f/64. Having already worked under Edward Weston, Van Dyke became an assistant for the noted Pictorialist Anne Brigman whose studio was located in a converted barn at 683 Brockhurst Street, San Francisco. In 1930, when Brigman moved away, Van Dyke and Mary Jeanette Edwards took over the studio from where they launched gallery 683. As Van Dyke recalled, the gallery was both a way to create "an atmosphere on the West Coast that could be useful to Western artists," and a way of "thumbing our nose at the New York people who didn't know us." Indeed, Van Dyke and Edwards named the gallery as an ironic challenge to Stieglitz's influential 291 gallery.

In 1931, at the University of California at Berkeley, Van Dyke met Preston Holder who had admired some of Van Dyke's photographs on display at a local bookstore. The two men became close friends and colleagues, and, during a long afternoon discussion, Holder suggested forming a group of Bay Area photographers. Van Dyke wrote later, "I was excited about the idea; it appeared to me that this would provide an opportunity to make a strong group statement about our work [...] I, for one, felt that it was time for the Eastern establishment to acknowledge our existence."

In 1931, Van Dyke held a party at 638 in honor of Weston, whose photographs were being shown at San Francisco's M.H. de Young Memorial Museum. The guests included Adams, Noskowiak, Cunningham, Edwards, and Swift. Van Dyke recalled their historical meeting as follows: "I presented the idea of our working together. I said besides that I've got a wonderful name for it, U.S. 256 [after the old rapid rectilinear lens that Weston used to get the maximum depth of field and to make his negatives appear sharper]. Well there was this kind of blank look around the room and then Ansel [Adams] who was the scholar of the group, said, 'Oh, you mean in the uniform system 256 equals f 64. But don't you think f 64 would be a better name. Nobody is going to be using the uniform system much longer and besides that beautiful f followed by a 6 and 4, and he drew it out, like that and you could suddenly see the cover of the catalogue or the announcement and the graphics were there and Ansel won."

The Group's First Museum Exhibition, 1932

On November 15, 1932, Group f/64 (the "/" between letter (f) and number (64) soon replaced the "." without ceremony or ado) made its public debut at the M.H. de Young Museum. The show, which concurred with the publication of Weston's The Art of Edward Weston (and was available for signing at the exhibit) included nine photographs each by core members, Adams, Cunningham, Weston, Edwards, Noskowiak, Swift, and Van Dyke, and four each by "invited" members Holder, Kanaga, Brett Weston and Lavenson. In its glowing review of the exhibition, The San Francisco Chronicle praised the "beautiful work on view [....] These photographers, like other talented brethren of the lens, are admirable portrait artists, imaginative creators of abstract patterns, who look for charm in boats, in scenery, in every small growing thing that is nourished at the bosom of Mother Earth."

The Group f/64 manifesto, written by Van Dyke and unveiled at the exhibition, featured a number of recommendations in support of what it called "qualities of clearness and definition." The manifesto also stressed that the objective of the Group was to promote "the best contemporary photography of the West" and that, in addition to work by its members, Group f/64 exhibitions would "include prints from other photographers who evidence tendencies in their work similar to that of the Group." It continued that the Group would limit "its members and invitational names to those workers who are striving to define photography as an art form by simple and direct presentation through purely photographic methods."

The exhibition travelled to the Seattle Museum of Arts, Portland Museum of Art, and also showed locally at Mills College, 683 Gallery, Adams's Geary Street gallery, and the Denny-Watrous Gallery in Carmel. Art historian Therese Heyman summed up the overall impact of the show thus: "Seen together, the images established a varied but singular point of view. For the most part objects were seen closely, framed by the sky or similarly neutral backgrounds. Nothing was moving, and there was a great deal of attention to the finely detailed surface textures of the subjects [...] The subjects were ordinary in the sense that they were encountered frequently, yet most had a commanding presence when photographed."

Gaining Notoriety through Camera Craft Magazine

Art critic Sigismund Blumann reviewed the exhibition for Camera Craft in May 1933. Blumann was a committed Pictorialist and had attended the show with a degree of scepticism. However, the exhibition changed his preconceptions: "The Group is creating a place for photographic freedom" he enthused.

Before Blumann's intervention, Camera Craft had been closely associated with West Coast Pictorialism, exemplified by the likes of William Mortenson. Mortenson had become known initially for his soft focus, staged portraits of Hollywood celebrities, but by the 1930s he was creating macabre and scandalous composites (such as L'Amour (1935)). Following Blumann's unexpected praise for the f/64 exhibition, Mortenson, who categorically denounced Group f/64, and their pursuit of a pure realism as leading up a "blind alley," engaged Adams in contentious exchanges in the 1933-1935 issues of the magazine. Deriding Mortenson's work for its dated Pictorialism and its salacious worldview, Adams, assuming to speak on behalf of Group f/64 as a whole, was vitriolic in his criticism, calling Mortenson the "Anti-Christ" and suggesting that he should perhaps "negotiate oblivion." As far as Camera Craft was concerned, Adams would win the day, and in 1934 he was invited to write a number of articles for the magazine with the result that Group f/64 had usurped Pictorialism as the leading West Coast movement.

Cunningham, Weston, and Adams

Though Group f/64 was a collective, three individuals in particular, Imogen Cunningham, Edward Weston and Ansel Adams, helped shape the pantheon of 20th-century American photographers. Moving from Oregon to the Bay Area in 1920, Cunningham became an early pioneer of West Coast Straight Photography. The Pictorialist Gertrude Käsebier had been an important influence on her earliest work, but, while on a visit to the East Coast, she made the acquaintance of Stieglitz and Strand. Their commitment to Straight Photography had a marked impact on her own practice and nowhere is this more evident than in her striking 1920 abstraction Mills College Amphitheater. Cunningham's vocational and personal circumstances were such however - she was a wife and mother to three young children, and she came from a scientific background in botany - that she was drawn to photograph botanical specimens available in her own garden, producing a remarkable series of magnolias between 1922-1925.

By the time Group f/64 was formed, Weston was already well known for his art and his outspoken views on Pictorialism (as such, he was often seen as the group's talisman). Like Cunningham, Weston had turned his back on Pictorialism in the early 1920s and his career only started to take shape when he moved from Chicago to California (via a short spell in Mexico) around the same time. Weston's high-resolution photographs of organic forms and modern marvels encouraged spectators to consider the essence of mundane objects and to look afresh at what was familiar. As he said, "The camera should be used for a recording of life, for rendering the very substance and quintessence of the thing itself, whether it be polished steel or palpitating flesh."

Adams, a renowned landscapist, met Weston in 1927 and Paul Strand in 1930, both of whom excelled at the modern photographic still life. Although he was critical of Weston's extreme close-up photographs of objects (including his famous Pepper (1930)) Adams had been impressed by Strand's use of Straight Photography to bring out new aspects in inanimate objects. It was through Strand indeed that Adams began to understand that Straight Photography could stand as an expressive art form in its own right. Adams had already received some measure of success as a photographer, but following his meeting with Strand, he discarded altogether soft focus and textured paper, and began working with a smooth, glossy paper that enabled the sharp detail he now strived for. Speaking in Weston's defence in a 1933 issue of Creative Art, however, Adams praised his fearless colleague because he "dared more than the legion of brittle sophisticates and polished romanticists ever dreamed."

Group f/64: Concepts, Styles, and Trends

The Californian Climate

Photography has played a decisive role in Californian culture since the days of the Gold Rush of 1848, and though Straight Photography was a practice associated with almost any photographer who denounced Pictorialism (including Alfred Stieglitz, László Moholy-Nagy, Manuel Alvarez, Berenice Abbott, Walker Evans and Robert Capa), Group f/64 were in fact a close-knit cadre of West Coast photographers in debt to their unique Californian environment. The Group's search for aesthetic purity meant that they were well served by their natural landscape (they were in close proximity to mountains, the ocean and deserts) and a sunny and often cloudless climate that enabled their search for aesthetic effects through natural light sources to eliminate the need for unnecessary post-processing. As art historian Therese Thau Heyman observed "Light was the only legitimate medium for photography, and much of the success of an artist photographer lay in controlling it. [And in] the West, light meant sunlight."

West Coast Liberalism

Adams clearly saw Group f/64 as being concomitant with the ideology of Bay Area liberalism when describing it as "an organization of serious photographers without formal ritual of procedure, incorporation, or any of the limiting restrictions of artistic secret societies, Salons, clubs or cliques." These sentiments also sat well within the Golden State's progressive cosmopolitan culture that grew out of the arrival of the estimated 300,000 'forty-niners," many of them immigrants, in search of gold (in 1849). Indeed, Adams extended the Group's invitation to "any photographer who in the mutual favorable opinion of all of us, evidences a serious attitude, a good straight photographic technique, and an approach that is basically contemporary." He appended this invitation with the gentle caution however: "friendly but frank disagreements exist among us" (a coded reference, perhaps, to his professional relationship with Weston).

Art-for-Art's-Sake

While others (no one more so in fact than the father of Straight Photography himself, Paul Strand) had turned away from pure abstraction in the name of New Politics, Weston remained steadfast in his commitment to the pursuit of a pure beauty. The American nation was trying to rebuild after the financial crash and critics had begun to question the very premise of fine art. Members of Group f/64 were thus criticized for failing to consider economic or social problems (the implication being that they were self-absorbed "artistes"). Weston observed as early as 1932 that there were "'right thinkers' who would have preferred that art function as a missionary to improve sanitary conditions" while adding a year later that he remained "'old fashioned' enough to believe that beauty - whether in art or nature, exists as an end in itself." Indeed, Weston did nothing to distract from the criticism when he concluded by saying that he could not "see why nature must be considered strictly utilitarian when she bedecks herself in gorgeous color [and] assumes magnificent forms."

Later Developments - After Group f/64

In 1935, Group f/64 came to an end as a movement. Van Dyke moved to New York, gallery 683 was sold, Cunningham began working for Vanity Fair, and Weston moved to Santa Barbara. As the effects of the Great Depression wore on, the art movement Social Realism gained traction. Straight Photography often served the cause of Social Realism as photographers, such as Dorothea Lange and Walker Evans became celebrated for their searing images of the Great Depression's human cost. Lange, who lived in San Francisco, was in fact invited to join Group f/64 but she turned the offer down. Indeed, Lange's images moved Van Dyke to such an extent he abandoned still photography altogether in favor of filmed documentary which he felt offered more possibilities for social change.

However, Weston and Adams continued developing their own practice of Straight Photography in the following decades, and Group f/64 had a lasting impact on Californian art institutions. Influenced by the de Young exhibition, arts administrator Ted Spencer recruited Adams in 1945 to develop a photography department at the California School of Fine Arts, already known for its prestigious painting faculty through which Mark Rothko, Clyfford Still and Elmer Bischoff had passed. Adams became a noted teacher, influencing the photographers Minor White, Frederick Sommers, and subsequent photographers including Harry Callahan.

Weston's work influenced Paul Caponigro, Wynn Bullock, and his son Brett Weston, and later photographers including Aaron Siskind, Jan Groover, and Ray Metzker. Group f/64's emphasis on the sharply focused close-up and the formal elements of the image remained fundamental to the development of Abstract Photography generally. At the same time, the Group's images remain widely popular, culturally specific, and established a lasting tradition in still life and landscape photography throughout the United States.

Useful Resources on Group f/64

-

![Ansel Adams BBC Master Photographers (1983)]() 192k viewsAnsel Adams BBC Master Photographers (1983)Our Pick

192k viewsAnsel Adams BBC Master Photographers (1983)Our Pick -

![Ansel Adams: Technique & Working Methods]() 81k viewsAnsel Adams: Technique & Working MethodsGetty Museum

81k viewsAnsel Adams: Technique & Working MethodsGetty Museum -

![Ansel Adams: Visualizing a Photograph]() 36k viewsAnsel Adams: Visualizing a PhotographGetty

36k viewsAnsel Adams: Visualizing a PhotographGetty -

![Ansel Adams: Yosemite]() 9k viewsAnsel Adams: Yosemite

9k viewsAnsel Adams: Yosemite -

![Portrait of Imogen Cunningham - I Believe in Learning (Ch 1) Documentary]() 0 viewsPortrait of Imogen Cunningham - I Believe in Learning (Ch 1) DocumentaryOur PickGetty

0 viewsPortrait of Imogen Cunningham - I Believe in Learning (Ch 1) DocumentaryOur PickGetty

-

![Live! From Library: Group f.64 & Revolutionizing American Photography]() 5k viewsLive! From Library: Group f.64 & Revolutionizing American PhotographyOur PickMary Street Alinder lecture Walnut creek Library

5k viewsLive! From Library: Group f.64 & Revolutionizing American PhotographyOur PickMary Street Alinder lecture Walnut creek Library -

![Secrets of Edward Weston's Photography]() 67k viewsSecrets of Edward Weston's PhotographyAdvancing Your Photography / Talk with Kim Weston

67k viewsSecrets of Edward Weston's PhotographyAdvancing Your Photography / Talk with Kim Weston -

![The Weston Story]() 10k viewsThe Weston StoryLecture by Kim Weston

10k viewsThe Weston StoryLecture by Kim Weston -

![Photographing Ansel Adams & Imogen Cunningham]() 7k viewsPhotographing Ansel Adams & Imogen CunninghamLecture by Alan Ross

7k viewsPhotographing Ansel Adams & Imogen CunninghamLecture by Alan Ross - Conversations with Willard Van DykeNew Day Films

Ask The Art Story AI

Ask The Art Story AI

![Edward Weston: [Nude] (1925)](/images20/pnt/pnt_group_f64_3.jpg)