- 01 Manet And Monet

- 02 Monet's Despair

- 03 Artists at War

- 04 Naked Corruption

- 05 Impressionist Cartoons

- 06 Public Mockery

- 07 Manet's Love Child

- 08 Suffering for His Art

- 09 Sketchy Business

- 10 An Arresting Impression

- 11 The Tragedy of Bazille

- 12 The Impressionists in London

- 13 Monet's Mini-Studio

- 14 Artistic Sacrilege

- 15 Outside Inside

- 16 Smudged Glasses?

- 17 From Rags to Riches

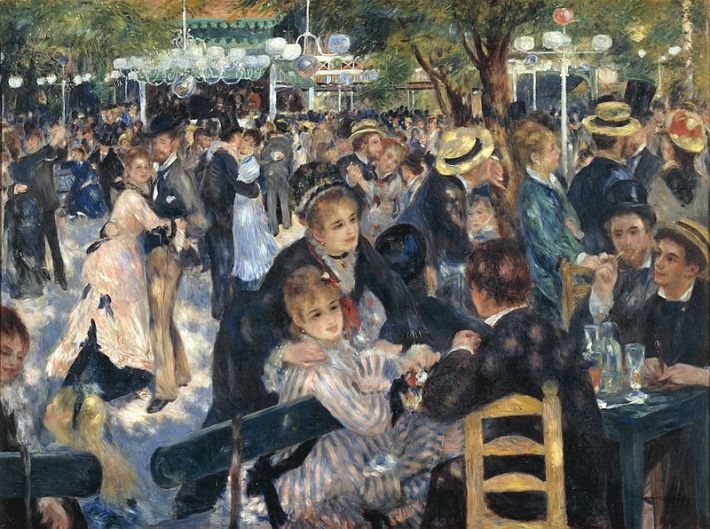

- 18 An Extra Sprig

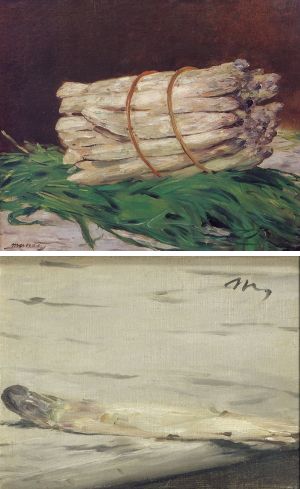

- 19 An Expensive Game of Cards

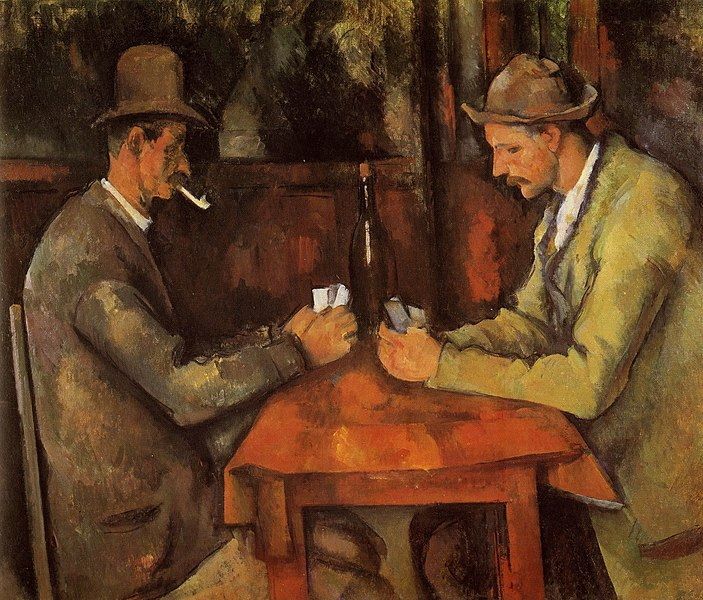

Impressionism Bonus Facts

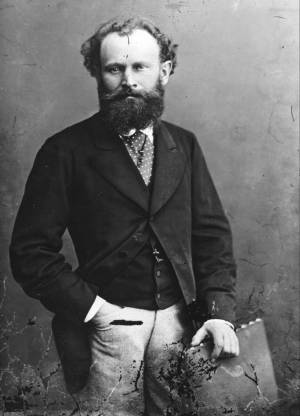

01 Manet And Monet

When Édouard Manet and Claude Monet's works were first exhibited together, during the Salon of 1865, many viewers and critics thought the two artists were the same person because of their similar names. Manet never quite let go of the suspicion that the newcomer had deliberately copied his name to trade off the notoriety he had established with his Le Déjeuner sur L'Herbe, and his equally provocative nude Olympia, displayed at that year's salon.

02 Monet's Despair

Latterly the most famous and perhaps most revered of the Impressionists, in 1868 Claude Monet was so depressed at his lack of money and success that he threw himself into the Seine, before coming to his senses in the water and swimming for the bank.

03 Artists at War

Many of the Impressionists suffered during the Franco-Prussian War of 1870-71. Camille Pissarro's House in Louveciennes, on the route of advancing Prussian soldiers, was converted into a slaughterhouse. His canvases were used as butchers' aprons, and sheep pens were built in his kitchen. The best part of 1,500 paintings, including works of Monet's stored in the house, were reportedly destroyed.

04 Naked Corruption

According to a story told by Pierre-Auguste Renoir, Paul-Durand Ruel, the Impressionists' main dealer and patron, had to bribe a Catholic New York customs official with donations to a church collection box in order to allow Renoir's nudes to enter the USA. Once they did, it was the North-American market that secured the Impressionists' fortune.

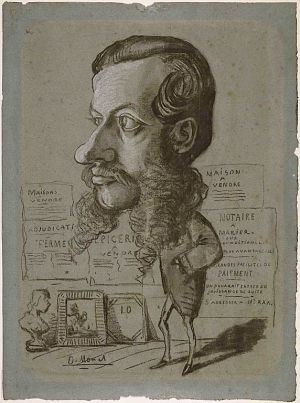

05 Impressionist Cartoons

Growing up in Le Havre, Claude Monet made a living for his family by selling sketch caricatures of local officials and dignitaries. He later remarked that he could have become a millionaire had he kept up this pursuit. Instead, it was a local artist's admiration for the sketches that helped convince Monet to become a painter.

06 Public Mockery

The Salon des Refusés was held in 1863 to exhibit works rejected from that year's official Salon. Though the event was organized by the French Emperor Napoleon III to placate angered avant-garde artists, the 70,000 visitors to the alternative salon went mainly to jeer at and insult the artworks, above all Édouard Manet's scandalous Le Déjeuner sur L'Herbe.

07 Manet's Love Child

Édouard Manet and his partner Suzanne, formerly his adolescent piano teacher, are believed to have had a child out of wedlock when Manet was young (though by some accounts the child was his father's). To avoid scandal, their son Léon lived with Suzanne's mother and was presented as her child until the death of Manet's father ten years later.

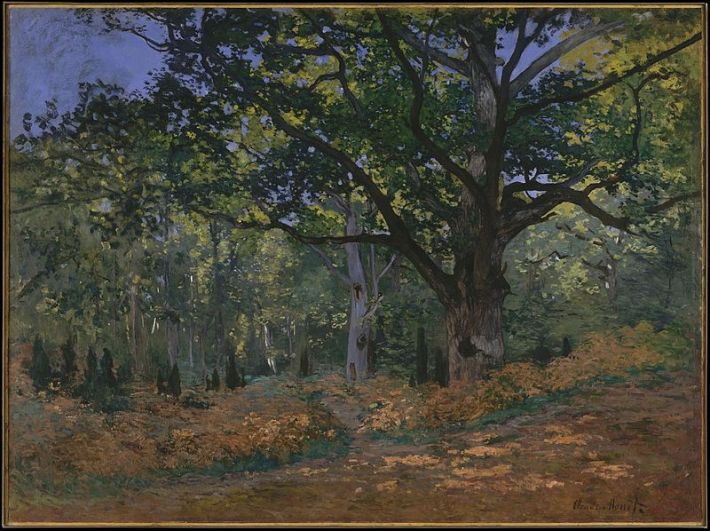

08 Suffering for His Art

Once, when painting en plein air in the Forest of Fontainebleau, the young Claude Monet was badly injured when he was struck in the leg by the stray discus of a practicing athlete.

09 Sketchy Business

Though their paintings now command extraordinary prices at auction, the Impressionists suffered for decades from poor sales, and were often less than shrewd businessmen. The Post-Impressionist painter Paul Cézanne, known to the Impressionists as a strange contemporary, once gave a just-completed painting for free to a man on the street after he said he admired the trees in it. Afterwards, Cézanne rushed to tell Monet and Renoir that he had made a sale. On another occasion, a raffle was held in Montmartre by a local pastry chef and friend of the Impressionists, with a painting by Pissarro as a prize. But the little girl who won the painting replied that she'd rather have a cream bun.

10 An Arresting Impression

During the occupation of Paris by the left-wing Communards, Renoir was mistaken for a government spy as he stood sketching the River Seine. He narrowly escaped a summary public execution, after being recognised by a young republican journalist and friend who was acting Chief of Police for the Commune.

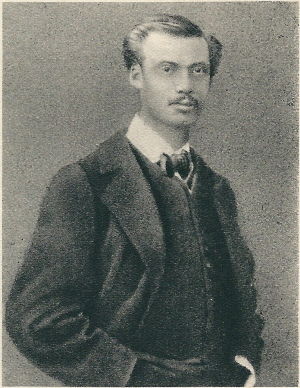

11 The Tragedy of Bazille

The Impressionist painter Frédéric Bazille was killed in the Franco-Prussian War when commanding a unit in place of an injured officer during the Battle of Beaune-la-Rolande. His heartbroken father dug in the snow-covered battleground for ten days to find his body, which he took back to the Bazilles' home-city of Montpellier on the back of a peasant's cart.

12 The Impressionists in London

Impressionism became popular in Britain partly due to the Franco-Prussian War. Monet, Pissarro, and the Impressionists' main dealer Paul Durand-Ruel all fled to southern England when the war took hold in Paris. Pissarro sketched the hamlets and villages south of London, while Durand-Ruel set up a studio in New Bond Street. It was in London that he met Monet for the first time, and began to patronise his work.

13 Monet's Mini-Studio

In order to paint the play of light on water up close, Monet had a tiny studio installed on his boat, and would paint in it with his knees drawn up to fit inside.

14 Artistic Sacrilege

The first Impressionist exhibition of 1874 was a commercial and critical disaster, castigated by press and public alike; the first art tutor of Berthe Morisot, one of the artists included in the show, told her mother that as penance Berthe "should go to the Louvre twice a week, stand before Correggio for three hours, and ask his forgiveness."

15 Outside Inside

Édouard Manet once remarked to the painter Berthe Morisot that he felt the Impressionists' famous plein-air painting technique was overrated, noting that "[y]ou can do plein-air painting indoors by painting white in the morning, lilac during the day and orange tones in the evening."

16 Smudged Glasses?

Monet's famous series of paintings of the Gare Sant Lazare was created in mockery of a critic who had once stated that looking at an Impressionist painting was like having a smudge on your glasses. Monet decided to depict the foggiest, smokiest subject-matter he could think of.

17 From Rags to Riches

When Renoir's Dance at Le moulin de la Galette (1876) was sold at auction for $78.1 million in 1990, it became for some time the second most expensive painting in the world. The irony of the painting's fame is that Renoir created the work to celebrate the lives of the working poor in Montmartre, then a lively but run-down semi-rural district on the outskirts of Paris.

18 An Extra Sprig

Manet's still life A Bunch of Asparagus was commissioned by his patron Charles Ephrussi for 800 francs. Ephrussi was so pleased with the work on completion, however, that he paid Manet 1000 for it. In gratitude, Manet painted him an extra sprig, sending the second painting to Ephrussi with a note reading "there was one missing in your bundle."

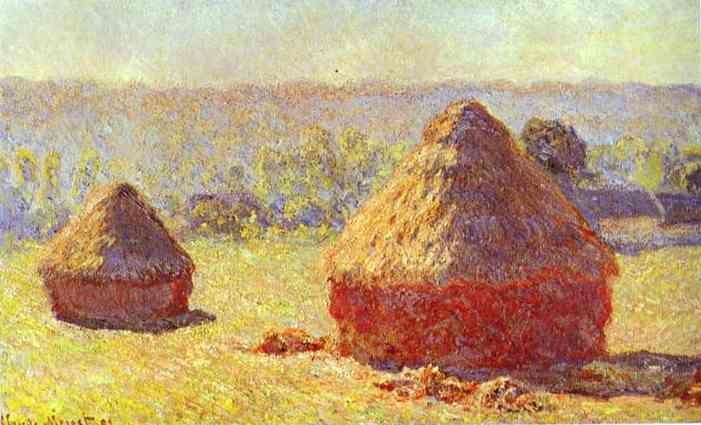

19 An Expensive Game of Cards

The Impressionists and their peers feature highly on lists of the most expensive artworks ever sold, with paintings from Monet's Haystacks series appearing more than once on most rankings. The most recent of the group to top the list, however, is Paul Cézanne, whose Card Players was sold for $225-300 million in 2011, only knocked off the top spot when Leonardo da Vinci's Salvator Mundi was auctioned off for $450.3 million in 2017.

More Impressionism

20 Abstract painting before and after Impressionism

Impressionism is often seen as the first modern art movement, partly because it was the first movement in painting to make formal abstraction - that is, the rejection of obviously realistic representation - a central aspect of its approach. Abstraction in art prior to Impressionism was often more subtle, and could be dependent on the mannerisms and eccentricities of individual artists. After Impressionism, the evolution of abstraction became an absolutely vital element of the story of art.

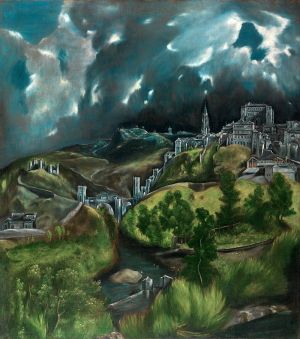

One historical era associated with abstraction in art is the Mannerism period (roughly 1520-1600), often known as the Late Renaissance, when artists began to play with, exaggerate, or embellish the qualities of beauty, formal harmony, and order developed during the Renaissance. One of the most extraordinary artists of this period was El Greco, whose works were beloved by modern artists such as the Cubists because of their strange and captivating use of proportions and perspective.

Later, artists of the Romantic era, from around the late 18th century to the mid-19th century, often worked with exaggerated brushwork and color palettes, and exaggerated forms and perspectives, to emphasise the emotional impact of the scenes they painted. The English Romantic landscape painter J.M.W Turner created extraordinary seascapes where hazy brushwork evoking sea and sky seemed to encompass the whole canvas. The French Romantic painter Eugène Delacroix often created paintings with loose brushwork, where bodies and forms seemed to be stretched or contorted.

From the mid-19th century onwards, French artists such as the Camille Corot began to use abstraction in a slightly more pronounced way. Corot, who often painted forest scenes, was interested in using fuzzy or mottled brushwork to show the play of light on foliage. In making light a subject of compositional interest though abstract formal techniques, he was a huge influence on the Impressionists.

The Impressionists, however, made far more central use of abstraction than any previous group of painters. From the early 1870s onwards, artists such as Monet used amazingly loose, quick brushwork to show the effects of light and other atmospheric qualities - fog, rain, mist - on the appearance of a scene to the viewer. In this they were hugely influential on many artists and movements to come.

Around the same time, the artist Paul Cézanne, a contemporary of the Impressionists, began to use abstraction in a different way. He experimented with breaking up the picture plane: that is, creating paintings where it seemed as if different parts of a scene were being viewed from different perspectives. Cezanne's work, like El Greco's would be very important for the Cubist painters of the early 20th century.

In the years following the Impressionist movement, the use of abstraction in art exploded. Painters from many different movements and countries started creating work that broke from realistic representation in myriad ways. French groups of the 1880s-90s, including the Synthetists, Nabis, Pointillists, and Post-Impressionists, used color and brushstroke in even more adventurous ways than the Impressionists, while in the early twentieth century a raft of movements, from Cubism to Constructivism to Expressionism, began to create abstract artworks with little or no basis in subject-matter at all. The Expressionist painter Wassily Kandinksy was amongst the first to create 'pure' abstraction in his work. But without the revolutionary gestures of the Impressionists, none of these advances might have been possible.

21 Landscapes before and after Impressionism

The Impressionists are often seen as the first artists to paint landscapes without adornment or embellishment, marking down only what they saw and felt. In fact, artists as far back as the seventeenth century had been engrossed with the natural world for its own sake. But the Impressionists were the first group to take to landscape painting with such singular intensity, and to set it on a pedestal amongst artistic genres.

In much historical Western painting landscape serves as mere backdrop to a mythical or historical scene. But the Dutch Masters of the 17th century were amongst the first artists to paint landscapes for their own sake, showing the cities, fields, and rivers of their lowland home. The most famous artists of this period include Rembrandt, Hercules Seghers, and Jacob van Ruisdael, whose Windmill at Wijk bij Duurstede (1670) is exemplary in its captivating naturalism.

Across the late eighteenth and early nineteenth centuries, landscape painters based in Northern Europe, such as J.M.W Turner and Caspar David Friedrich, created stirring pastoral, mountain, and sea scenes, expressing the Romantic spirit of the era.

During the middle years of the nineteenth century, painters began to focus on painting on location in beautiful natural environments, such as Fontainebleau Forest, where the "Barbizon School" congregated from the 1830s onwards. Among them was Camille Corot, whose soft natural scenes, often exploring the play of light on foliage, were a huge influence on the Impressionists.

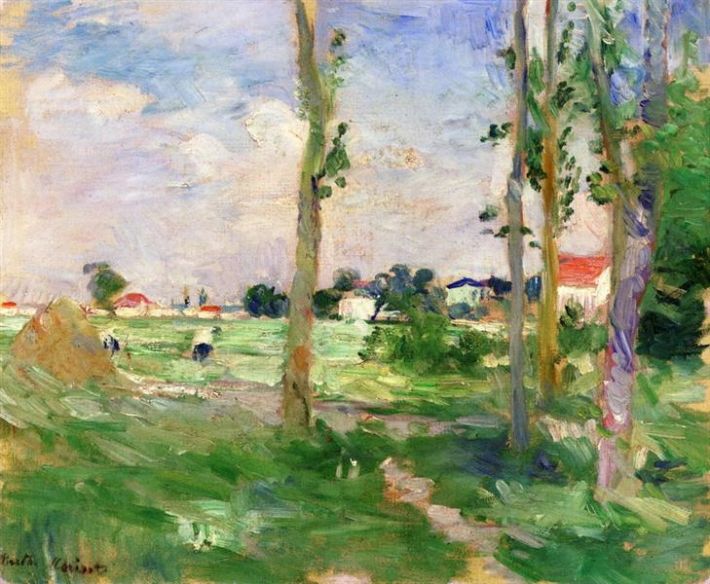

When the Impressionist group, including Claude Monet, Pierre-Auguste Renoir, Alfred Sisley, and Berthe Morisot, began to form in the 1860s, they took the effects of light that Corot and others had explored and pushed much further with their formal experiments. The wanted to relay the impression a landscape made on the eyes and senses at the moment of viewing. In so doing, they elevated landscape painting to a position of primary importance amongst artistic genres. While there were precedents for their work, never had landscape painting been so crucial to the ethos of an artistic group.

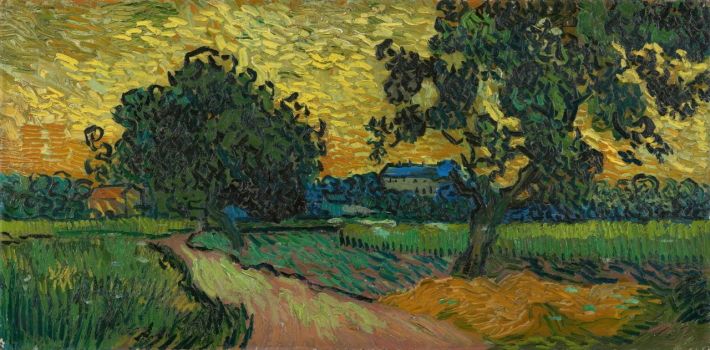

Ironically, the Impressionists' attention to momentary detail meant their work often looked more abstract, and less realistic, than older landscape works. In the decades following the Impressionists, artists exaggerated the abstract effects which they had discovered. Painters such as Vincent Van Gogh used more experimental colour palettes and more mannered brush strokes.

In the early twentieth century, groups such as the Expressionists and Cubists created ever more radical landscape works, fracturing the picture plane and playing with perspective, figurative accuracy, and truth to life; but these developments could still be traced back to the ground-breaking gestures of the Impressionists. Edvard Munch was amongst the famous artists of this period to create striking landscape paintings.

Although the late twentieth century and early twenty-first centuries have not produced famous landscape art movements, contemporary artists such as David Hockney and Peter Doig continue to work with the legacy of the Impressionist landscape with their dreamy, colourful, wild and rural scenes. While the Impressionists were not the first landscape artists, they made landscape painting vital to the story of art for the first time.

22 Serial artworks: from Monet to Warhol

Lots of modern artists have created sequences of works based on single subject-matter, but their reasons for doing so can be very different, and can teach us a lot about the contrasts and complexities of modern art. Two of the most famous artists to have worked in this way are Claude Monet and Andy Warhol. Their motives for creating works in sequence reveal radically opposed visions.

Claude Monet (1840-1926) was the figurehead of the Impressionist movement. His most famous sequence of works is the so-called "Haystacks" series, Les Meules à Giverny. This consists of 25 paintings created during 1890-91, depicting stacks of wheat in the fields outside Giverny, a village in northern France where Monet had lived since 1883. Monet's Impressionist philosophy meant that he was concerned not just with capturing a physical subject-matter, but also with representing a moment in time. The haystacks looked different to him with each passing hour: at day and at night; in spring, summer, autumn, winter. The changing weather, mood, and atmosphere created a different subject-matter in each of these settings. Monet's "Haystacks" series is about paying close attention, trying to capture a subject in all its minute, time-bound complexity.

Andy Warhol, the most famous artist of the Pop Art movement, had very different reasons for creating serial artworks. Amongst the many sequences of works he created based on his famous repeat-prints of Marilyn Monroe. Warhol created his first work in homage to Monroe, Marilyn Diptych, in 1962, shortly after the actress's death. For Warhol, the repetition of Monroe's face across this work, and across much of his subsequent work (using his screen-print technique), reflected the mass consumption and reproduction of her image: its conversion into an icon and sales product at the same time. The repetition of subject-matter was therefore not about capturing detail but about showing how pop culture devours and regurgitates images, particularly images of its heroes: distorting and degrading them in the process.

Serial artworks therefore stand for both sides of a key conflict within modern art: between desire for originality, the new, and an awareness that art is mediated through pop culture and the economy, and cannot escape the value systems they impose on it.

23 The Impressionist nude and after: from Manet to Saville

Édouard Manet caused a scandal when his nude portrait Olympia was displayed at the 1865 Paris Salon. Manet was associated with the Impressionists, so his daring work was seen to epitomise the scandalous nature of the new movement. But he was responding to a whole tradition of nude portraiture in Western art, and inspired later artists to grant the female nude more power and autonomy.

Women's bodies had held a central place in modern Western painting since the Italian Renaissance, and Titian had already taken the bold step of placing the female nude in a modern rather than mythological context with his Venus of Urbino (1538).

Manet's Olympia, however, caused controversy because the mythological context for nudity was gone. The name "Olympia", unlike "Venus," does not refer to a Greek god, but was one associated with prostitutes or 'courtesans' in late 19th century Paris. And unlike Titian's Venus, Olympia's gaze is confident, almost quizzical; she is not shy or coy. For the first time in Western art, Manet presented us with a modern woman defiantly confronting the viewer with her own sexuality.

Other artists were inspired by Manet's example. Picasso's Les Demoiselles D'Avignon ("The Young Ladies of Avignon") is a brothel scene like Manet's, but many of the models' faces are replaced with West-African masks (on the racist terms of the era, the masks stood for primal energy and unbridled sexuality). Like Olympia, the demoiselles stare intensely at the viewer. Combined with Picasso's angular, clashing picture planes, this made this painting almost as outrageous to audiences of the 1900s as Olympia had been to the audiences of the 1860s.

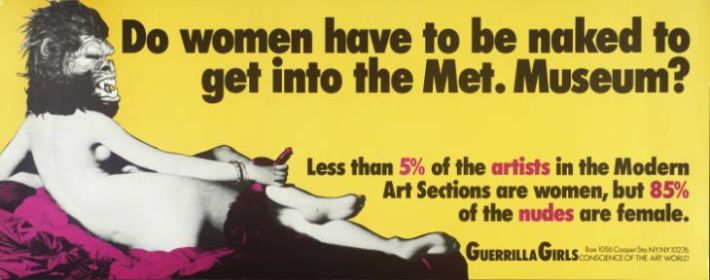

Of course, the painters depicting these scenes were all men, and the female nude was still a symbol of women's subjugation. But the twentieth century saw a significant movement towards recognizing women's role as artistic creators rather than mere subjects, often through acts of artistic activism. In 1914, the Canadian suffragette Mary Richardson, protesting against the imprisonment of her fellow campaigner Emmeline Pankhurst, slashed Diego Velázquez's nude The Rokeby Venus (1647-51) in London's National Gallery. In New York during the 1980s, a group of anonymous artists called The Guerrilla Girls created posters asking questions like "Do women have to be naked to get into the Met. Museum?"

From the late twentieth century onwards, women artists have depicted the female nude with more physical and psychological naturalism than was previously possible. The works of the British artist Jenny Saville, such as Propped (1992), are a good example of this. Though Saville's works are very different from Manet's, they indicate the legacy of Olympia, the first female subject in modern art to return the viewer's gaze in a way that expressed her own identity, not the desires or fantasies of the artist.

Acknowledgements

Some of the facts on this page come from Sue Roe's The Private Lives of the Impressionists (Chatto & Windus, 2006)

Ask The Art Story AI

Ask The Art Story AI