Summary of Medieval Art

The Medieval age accounts for the thousand-year period between the fall of the Western Roman Empire (in 476), and with it the end of the age of Classical Antiquity, and the beginnings of the European Renaissance. Spreading throughout Europe and beyond the category of Medieval art accounts for the emergence of many national movements that, between them, reflected the heritage of the Roman Empire, the iconographic style of the early Christian church, and/or the "barbarian" cultures of Northern Europe. Although dismissed by early historians as the art of the "dark ages", today, Christian and Byzantine art, Anglo-Saxon and Viking art, Carolingian art, Ottonian art, Romanesque art, and Gothic art, have all secured their rightful place as key markers in the timeline of art history.

Key Ideas & Accomplishments

- It was the 14th century Italian poet and scholar, Petrarch, who, first labelled the period between the fall of the Roman Empire and the Renaissance of the early 14th century, as the "dark ages". For Petrarch and his followers, it was a period of intellectual and creative "darkness" that followed the age of Classical learning and enlightenment. Having been written off as a kind of artistic inertia that divided the glorious periods of Classical Art and the rise of the Renaissance, today the period of Medieval art is seen as indispensable in what it tells us about the ways in which religious and secular arts evolved hand-in-hand.

- The Medieval age accounts for the time when Christianity came to dominate progressive European thinking. It saw the rise of universities, the rule of civil law, and many different versions of religious reform. The visual arts, so vital during a period when literacy was reserved for the elite classes, became a key instrument of religious enlightenment, giving rise to the creation of icons, reliquaries, altarpieces, and illuminated manuscripts for church use and for private devotion.

- Medieval art is associated with Christianity and the building of cathedrals and churches, but the period accommodated the rise of a secular (or "earthbound") art too. Indeed, the latter could unify with the Christian church and the sacred arts associated with it. For example, it became commonplace for both Eastern and Western emperors to commission art pieces featuring images of themselves juxtaposed with biblical art. This practice served to highlight the emperors' devotion to God, and to reinforce the belief amongst the people that their divine right to rule on earth was decreed by God himself.

- In a period sometimes referred to as the Migration Period (300-900), large areas of the Western Roman Empire fell to invading forces from the North. These factions brought their own pagan influences to bear on Medieval art. The arts and culture of these migratory groups gave rise to an elaborate decorative style with utilitarian objects and jewelry, often featuring abstract carvings of animal motifs. Northern groups such as the Vikings and the Saxons have left behind a rich arts and crafts legacy in fields including pottery, textiles, woodwork, and metalwork.

Overview of Medieval Art

According to author Veronica Sekules, "the visual arts played a distinctive part in the intellectual history of the Middle Ages, not only as a means of demonstrating the shaping of ideas, but also in highlighting the connections between different branches of learning. [...] there was a number of genres of imagery that had the capacity to draw from these and allude to wider ideas with great subtlety and precision".

Artworks and Artists of Medieval Art

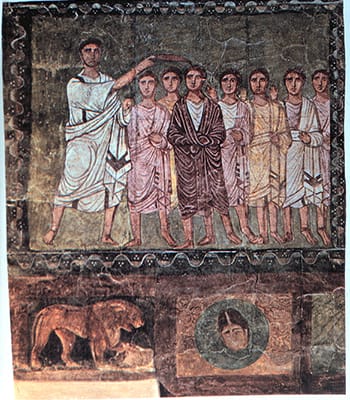

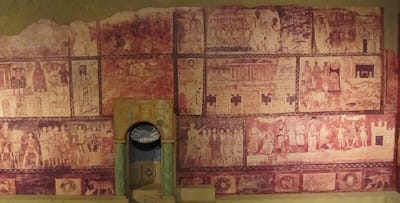

Samuel anoints David

This fresco is one of several biblical scenes painted on a third century Jewish synagogue wall in Dura-Europos, in present day Syria. The scene depicts verses from the Old Testament book of First Samuel in which, following God's choice for a new leader of Israel, the prophet Samuel anoints young David's head with oil pronouncing him, King. The scene itself is characteristic of early religious work from the Late Antiquity period. Figures are depicted as flat forms, without modelling, giving the appearance that their feet are not stood on the ground. There is also a hierarchical aspect to the work in which the most important figures are distinguished. In this case Samuel is depicted as larger than the other figures, while David is wearing a more detailed and brighter, purple colored robe. Nor is the scene without symbolism. As author Fred Kleiner notes, "purple was the color associated with the Roman emperor, and the Dura artist borrowed the imperial toga from Roman state art to signify David's royalty".

The work, thought to be one of the earliest examples of Jewish or Christian art in history, was created in the third century CE when those practicing these faiths were still being persecuted. As a result, any form of worship had to be conducted in secrecy. This work was in fact found painted on the wall of a room in the back room of a home that was used as a secret synagogue. Its hidden location indicates that, while forced to do so at great personal risk, early believers were still strongly motivated to express their faith visually. According to Kleiner, "the discovery almost a century ago of the elaborate mural cycle in the Dura synagogue initially surprised scholars because they had assumed that the Second Commandment (Exodus 20:4-6), which prohibits Jews from worshiping images, precluded the display of figural scenes in houses of worship. It now seems that narrative scenes such as those at Dura were features of many Late Antique synagogues".

Tempera on plaster - Main interior wall of the synagogue in Dura-Europos, Syria

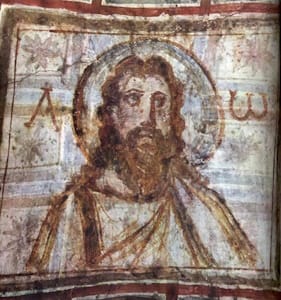

Detail from the Story of Jonah

This scene is one of several on the walls of a Roman catacomb depicting the story of Jonah. In this famous Old Testament story, Jonah rejects God's request to become a prophet. An angry God duly causes a devasting sea storm as fellow mariners throw Jonah overboard in an attempt to quell God's rage. A giant whale swallows Jonah, and while in the beast's belly, he prays to God for three days before the whale expels him, at which point Jonah assumes his calling as a prophet. Here we see the moment the sailors throw Jonah from the ship as a sea serpent (representing the whale) anticipates Jonah's plunge into the water. The narrative is rendered through the simplification of form and minimal detailing that is typical of the earliest Christian works; there is no sense of depth or dimensionality, here, and no proportional harmony between the figures and the ship.

This fresco in one of the earliest forms of public Christian art and underlines the fact that, once Christians were able to practice their faith without fear of persecution, the Roman catacombs (hitherto the burial site of earlier Christians) began to be decorated with biblical narratives. Indeed, the practice follows in a long custom of burial decorations that harkens back to tombs of the Ancient Egyptians. This work also reveals a dominant tendency in the art of this period. In early Christian art, Christ was often depicted as either as a teacher or a shepherd. His death was never shown through images of the crucifixion. Rather, references to his "second coming" were symbolized through the parable of Jonah and the Whale; the three days Jonah spends in the whale's belly widely understood as a reference to Christ's resurrection (after three days). The fresco was a fitting subject for a Christian burial space where it supported the belief that Christians would be "reborn" with Jesus in Heaven.

Tempera fresco - Catacomb of Saints Peter and Marcellinus, Rome, Italy

Sarcophagus of Junius Bassu

An elaborately detailed relief sculpture, this sarcophagus, or stone coffin, features ten different scenes from the Old and New Testaments, each separated by columns. The coffin was made for a wealthy Roman, Junius Bassus, who had converted to Christianity before his death and wanted his final resting place to reflect his faith. Depictions of Jesus are in the middle section of both rows while additional stories include (on the bottom row from the left) a scene featuring Job, Adam and Eve in the Garden of Eden, Daniel's trial in the lion's den, and Paul's arrest. On the top row the scenes include Abraham's sacrifice of Isaac, the arrest of the apostle Peter, and two scenes of Jesus on trial before his crucifixion. Christ on the bottom row center is shown on his journey into Jerusalem, while on the top row he is shown seated in Heaven surrounded by Saints Peter and Paul.

When one looks closely at the relief, it becomes apparent that there is only one instance, in the center scene on the top row, where a figure, Christ, looks directly out at the viewer. He has died and risen from the dead and is now seated in Heaven. The portrayal of a frontal figure like this dates back to depictions of Roman emperors in grandiose scenes where, by staring directly out at the viewer, the emperor's authority was effectively confirmed. The elevation of Christianity as ranking above all other belief systems is visibly reinforced in the depiction of Christ's feet resting on the head of the mythological sky god. Says author Fred Kleiner, "in the upper zone, Christ, like an enthroned Roman emperor, sits above the sky god, who holds a billowing mantle over his head, indicating that Christ is ruler of the cosmos".

Marble - Museum Storico del Tesoro della Basilica di San Pietro, Rome

Suicide of Judas and Crucifixion of Christ

This small ivory plaque, measuring a little more than three by three inches, is rich in detail. On the right, Christ is impaled on the cross. His mother Mary and the apostle John stand on the left, sombre in grief, while on the right a man thrusts his spear into Christ's side to test if he is dead. On the far left side of the plaque another man is facing death: Judas, the apostle, has hung himself from the branch of a tree. Beneath his feet is an open bag of coins which are spilling from the ground; the money he received for betraying Jesus.

This work is one of a series of plaques which depicted the death and resurrection of Christ. Each plaque was nailed into the sides of a small box which had utilitarian and devotional uses. It is one of the first works to show Christ's death (rather than allude to it through the parable of Jonah and the Whale). Author Fred Kleiner writes, "In the Crucifixion scene [...] one of the earliest known renditions of the subject in the history of art [...], the Savior exhibits a superhuman indifference to pain. Jesus is a muscular, nearly nude, heroic figure who appears virtually weightless. He does not hang from the cross. He is displayed on it - a divine being with open eyes who will be resurrected, not the mortal condemned to death by Pontius Pilate [...]. The striking contrast between the powerful frontal not suffering Jesus on the cross and the limp, hanging body of his betrayer [Judas] with his snapped neck is highly effective, both visually and symbolically".

Ivory - British Museum, London, England

Church of Holy Wisdom (Hagia Sophia)

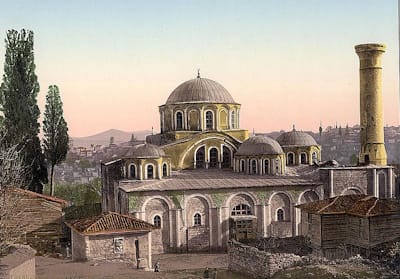

Church building was a dominant aspect of Byzantine architecture, with the Church of Holy Wisdom (or the Hagia Sophia as it is known today) standing as the crowning achievement of its age. Kleiner writes, "In Constantinople alone, [Emperor Justinian] erected or restored more than 30 churches of the Orthodox faith. Procopius, the official chronicler of the Justinianic era, admitted that the emperor's extravagant building program was an obsession that cost his subjects dearly in taxation. But Justinian's monuments defined the Byzantine style in architecture forever after". In building this church, Emperor Justinian was asserting his own faith, the legitimacy of Christianity over all other religions, and the superiority of the Eastern Roman Empire over all other civilizations.

Historian Fergus Bordewich describes how, "until the 15th century, no building incorporated a floor space so vast under one roof. Four acres of golden glass cubes - millions of them - studded the interior to form a glittering canopy overhead, each one set at a subtly different angle to reflect the flicker of candles and oil lamps that illuminated nocturnal ceremonies. Forty thousand pounds of silver encrusted the sanctuary. Columns of purple porphyry and green marble were crowned by capitals so intricately carved that they seemed as fragile as lace. Blocks of marble, imported from as far away as Egypt and Italy, were cut into decorative panels that covered the walls, making the church's entire vast interior appear to swirl and dissolve before one's eyes. And then there is the astonishing dome, curving 110 feet from east to west, soaring 180 feet above the marble floor".

The symbolic power of the church continued after the Ottoman Turks conquered the Roman Empire in 1453. The Turks converted the church to a mosque, renaming it the Hagia Sophia. It was at this point that the minarets were added. In 1935, the Mosque was converted into a museum where both Islamic and Christian art were displayed side-by-side. In 2020, the Hagia Sophia was converted back to a mosque.

Anthemius of Tralles and Isidorus of Miletus - Istanbul, Turkey

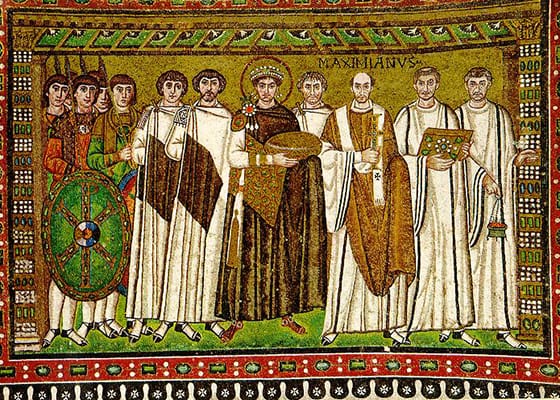

Justinian, Bishop Maximianus, and attendants

This mosaic is one of two similarly themed works in the apse of the Byzantine San Vitale Church in Ravenna, Italy. Here, Emperor Justinian is shown standing in the center of a group of men wearing a purple robe and holding a bowl used to hold the bread of the Eucharist. On the right side of the Emperor is the Bishop Maximianus dressed in a yellow robe. To the left are other members of the clergy and soldiers in the Emperor's imperial guard. Typical of the art of this period, the way the figures are depicted is rich in symbolism. Justinian is in the center of the work and the dark color of his robe, not only sets him apart from the others, but also links him to Christ (as it is the color he was most often depicted in during this period). Also, a halo surrounds Justinian, which is indicative of how holy figures were depicted at this time. These elements combine to reassert the belief that Justinian is linked to God, and as so, his right to rule is divinely given.

This mosaic, and a mosaic of the Empress Theodora positioned directly opposite, are located in the apse of the church by way of a reminder to parishioners that Justinian donated the money to build this church. The faith of the Emperor is reinforced by the fact that both mosaics are positioned directly below the image of Christ sitting atop the world as if in Heaven (in another mosaic positioned at the upper-most section of the apse). This acted as visual confirmation that Justinian is both the ruler of the empire, and a man of God. Commenting on the golden background, author Fred Kleiner states, "the artist placed nothing in the background, wishing the observer to understand the procession as taking place in this very sanctuary. Thus, the emperor appears forever as a participant in the sacred rites and as the proprietor of this royal church and the rule of the western territories of the Eastern Roman Empire". This observation is not without a little irony when one learns that Emperor Justinian and his wife never once visited the church.

Mosaic - North wall of the apse, San Vitale, Ravenna, Italy

The Sutton Hoo Purse-Lid

This small piece of ornamental metal design is a cover lid for a Merovingian purse. Seven small plaques are set in the lid to display a rich sequence of geometric and figural patterns. The far left and right bottom plaques feature a man surrounded by two wolves, while in the center two panels show two eagles capturing another animal. Above are three plaques of curvilinear abstract designs. The plaques were formed by tiny strips of metal attached together and filled in with colorful gemstones and pieces of glass, and it is considered a masterpiece of cloisonné design, at which the Merovingians excelled.

This work is one of the treasures found with the excavation of a burial ship full of personal treasures from the Sutton Hoo burial mound in Suffolk, England. While only the most important of Merovingian individuals would have been buried in such grand fashion, it is believed by many that this ship, and this leather purse, belonged to a king. Generally, the work can serve as a good example of the importance that art played in the daily lives of the Merovingians since even simple daily items such as belt buckles, pins, and purses became, in their hands, works of aesthetic beauty. More than that, however, this work strongly hints at a symbolic meaning. According to the British Museum, the figural and animal designs on the purse lid, "must have had deep significance for the king and his subjects, but it is impossible for us to interpret them. The wolves could be a reference to the dynastic name of the family buried at Sutton Hoo - the Wuffingas (Wolf's People). Like the eagle, they are a powerful evocation of strength and courage, qualities that a successful leader of men must possess".

Gold, glass, garnet - British Museum, London, England

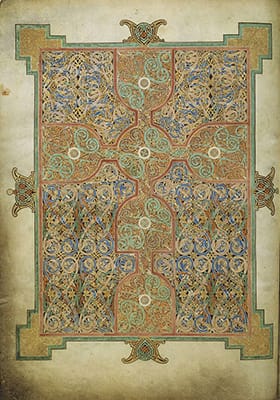

Cross-inscribed carpet page, folio 26 verso of the Lindisfarne Gospels

This highly detailed work on paper is part of an illuminated manuscript called The Lindisfarne Gospels. It is known as a carpet page because the page does not contain any text and was designed solely for decorative effect. The colors are vivid - reds, blues, greens, and gold - adding to the dramatic effect of the page which outlines a large cross in red. Author Fred Kleiner writes, "[the carpet page features] serpentine interlacements of fantastic animals [that] devour each other, curling over and returning on their writhing, elastic shapes. The rhythm of expanding and contracting forms produces a vivid effect of motion and change, but the painter held it in check by the regularity of the design and by the dominating motif of the inscribed cross". It is believed the book was written by a monk named Eadfrith shortly before his death, and includes the four books of the gospel and the letters of Saint Jerome.

Carpet pages, named such due to their resemblance to detailed oriental carpets, highlighted the importance placed on art during the Early Middle Ages given that, even with religious books, single pages could be dedicated to stand-alone illustrations (that is, independent of the written text). This work is considered one of the greatest examples of Hiberno-Saxon art, not least, because it shows, as Kleiner writes, "the marriage between Christian imagery and the animal-and-interlace style of the northern warlords".

Tempera on vellum - British Library, London, England

Round Box Brooch

The Vikings conquered lands that are now part of Britain, Ireland, and France. In addition to their legendary maritime prowess, the Vikings were great craftspeople and artisans. Their longships carried a symbolic threat through carved figureheads of menacing sea dragons, while the Vikings' costume wear and amulets typically featured carved animal motifs. Measuring just over two inches high, this box broach is typical of decorative Viking art. According to the Metropolitan Museum of Art, "Women on the Scandinavian island of Gotland wore box brooches to secure their shawls at the collarbone; the brooches doubled as a container to hold small objects. This example is decorated with tiny beasts, which inhabit the interlace patterns on the top and sides", while adding that, Viking art generally eschewed "figural decoration in favor of lively patterns based on stylized animals".

Vikings produced arts and crafts that were both functional and decorative. This piece confirms their skill at metalworking, as well as the Vikings' penchant for zoomorphic (animal themed) designs. While the 'tiny beast" borders on abstraction, there are four repeated creatures which curve inward, as if rolling itself into a protective ball. Historian Emma Groeneveld says of the broach that it is, "more abstract than [earlier Viking broaches], displaying long, almost ribbon-shaped, curving bodies with intertwining limbs that develop into open loops and tendrils. Their heads are small and shown in profile but have big, bulging eyes".

Copper alloy - Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, New York

Equestrian portrait of Charlemagne or Charles the Bald

This bronze sculpture, measuring nine and a half inches high, depicts a man seated on his horse. Wearing a crown and elegant royal robe, most historians believe the figure to be Charlemagne, the first Holy Roman Emperor and the man responsible for ushering in the Carolingian Era of Medieval history. This is a rare example of sculpture from the period when the religious art typically took the shape of illuminated manuscripts and small ivory relief carvings. The sculpture also alludes to the influence that Ancient Roman art had had on Charlemagne and the art and architecture of the Carolingian period more generally.

This statue is modelled after an early Roman work featuring the Emperor Marcus Aurelius. In both statutes the emperor is depicted significantly larger than their horse thereby emphasizing their power (greater even than the magnificent imperial horse on which they are seated) and the their divine right to rule. Of this sculpture, author Fred Kleiner writes, "[Charlemagne] is on parade. He wears imperial robes rather than a general's cloak, although his sheathed sword is visible. On his head is a crown, and in his outstretched left hand he holds a globe, a symbol of world dominion. The portrait proclaimed the renovation of the Roman Empire's power and trappings".

Bronze - Musée du Louvre, Paris, France

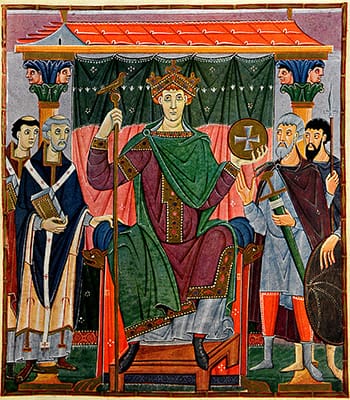

Otto III enthroned, folio 24 recto of the Gospel Book of Otto III

Derived from a Gospel book, this page features a depiction of Emperor Otto the Third, seated on a throne holding an orb with a cross in his left hand and a scepter in his right. He is surrounded by church clergy and government figures and is placed in front of a building structure supported with columns. Illuminated manuscripts - such as the Gospel Book of Otto III - were a commonplace during the Ottonian period. Here we can see an increased sense of realism in terms of the dimensionality of the figures. There is weight and body behind the imperial robes, while the Emperor's seated position on the throne also appears natural. His entourage is placed in a real landscape setting rather than the "floating" figures typical of early Christian art.

This work shows the power of art to serve as a vehicle for political propaganda. The book of the four gospels (of which this page is a part) was commissioned by Otto. While this would confirm his devotion to God, he went further by inserting his own image in the Gospel manuscript. His image reinforces his position as crowned emperor by holding the sceptre and orb. Moreover, the presence of the cross atop the orb, coupled with his positioning on a throne surrounded by his disciples, echoes representations of Christ, and thereby strengthening his divine right to rule. The architecture in this work is also significant. As author Veronica Sekules notes, during this period, "rulers are nearly always shown in some kind of architectural enclosure [...]. In general terms, the representation of architecture, or of architectural features such as fictive niches or arcades as settings for images, suggests status and civilization".

Tempera on vellum - Bavarian State Library (Bayerische Staatsbibliothek), Munich, Germany

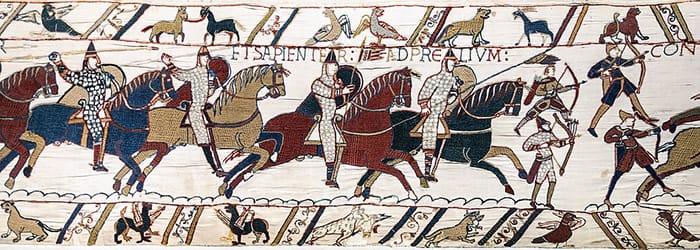

Detail of Bayeux Tapestry (featuring the "Battle of Hastings Norman Knights and Archers)

While titled the Bayeux Tapestry, this work is in fact an elaborately detailed and decorative work of embroidery. Measuring one foot eight inches high the piece is nearly two hundred and thirty feet long. Sewn into the linen scroll is a series of scenes depicting the history of England, including the Norman victory over the Anglo-Saxons at the Battle of Hastings in 1066 (referenced in the detail above) which ultimately united present day France and England under a Norman king's rule. It also features scenes depicting the death of Anglo-Saxon King Edward the Confessor, his funeral and burial at Westminster Abbey, and the crowning of William as King (all key historical events that led up to the Battle of Hastings itself).

This is probably the most famous example of a Medieval tapestry or embroidered work. The embroiderers took painstaking efforts to render incredible details from patterns on clothing and individual elements of architectural structures. The work features more than six hundred figures, 37 buildings, 41 ships and more than 200 animals, many of which are horses. These details combine in the seventy-five scenes that compose the work. Not surprisingly, the history of the Bayeux Tapestry is not without more fanciful stories about its origins. According to author Nora McGreevy, "popular myth holds that Queen Matilda of England and her ladies-in-waiting embroidered the sweeping tableaus, but historians don't actually know who created it". Author Fred Kleiner adds, "the Bayeux Tapestry stands apart from all other Romanesque artworks in depicting in full detail an event at a time shortly after it occurred, recalling the historical narratives of ancient Roman art. [The] story told on the textile is the conqueror's version of history, a proclamation of national pride".

Embroidered wool on linen - Bayeux Museum, Bayeux, France

Virgin of Compassion (Vladimir Virgin)

This icon depicts the Virgin Mary holding the infant Jesus Christ. Mary, in her familiar dark robe, embraces her son who rest his cheek on hers. As she holds him, Mary looks, not at her child, but out at the viewer. An important Byzantine icon, the work shows the flat, two-dimensional, forms and details typical of the period. The author Fred Kleiner identifies "the Virgin's long, straight nose and small mouth; the golden rays in the infant's drapery; the decorative sweep of the unbroken contour that encloses the two figures; and the flat silhouette against the golden ground" as typical of such icons. However, Kleiner adds that this example is a "much more tender and personalized image of the Virgin. [...] Here, Mary is the Virgin of Compassion, who presses her cheek against her son's in an intimate portrayal of mother and child. A deep pathos infuses the image as Mary contemplates the future sacrifice of her son".

By looking out at the viewer, it is as if Mary is asking the viewer to contemplate her son's future sacrifice and death. It is a picture that would be repeated throughout the Medieval and later periods. This work also speaks to the value that was placed on this and similar Byzantine icons. The icon had resided in several churches and devotees believed it had the power to keep people safe, and even bring about miracles. Indeed, it was believed by many Russians that the Vladimir Virgin had helped to save the city of Kazan from an enemy invasion, and later, the country from a Polish invasion. Today the Vladimir Virgin is considered one of the most culturally and historically significant pieces of Russian art.

Tempera on wood - Tretyakov Gallery, Moscow, Russia

Head Reliquary of Saint Alexander

Relics were an important part of the Christian faith during the Middle Ages and pilgrims would often make long and arduous journeys to pray in the churches that housed them. This reliquary, as described by author Fred Kleiner, "[features] an almost-life-size head, fashioned in beaten (repoussé) silver with bronze gilding for the hair. The idealized head resembles portraits of youthful Roman emperors such as Augustus [...] and Constantine [...], and the Romanesque metalworker may have used an ancient sculpture as a model. The saint wears a collar of jewels and enamel plaques around his neck. Enamels and gems also adorn the box on which the head is mounted. The reliquary rests on four bronze dragons - mythical animals of the kind populating Romanesque cloister capitals".

Relics of this type needed to be held in containers fitting of such sacred objects and so reliquaries became important objects in themselves. Highly detailed and embellished, this example was created to house the bones of Saint Alexander who was a pope of the Holy Roman Empire between 1061 and 1073. As many believed relics had healing powers, it was important the reliquaries respected this belief. Here, the box on which the head rests, carries images of the personifications of Virtues. As the Musées Royaux d'Art et d'Historie describes, "These Virtues crush sin, embodied in the dragon-shaped feet, and lead to holiness, represented by the silver head of the Pope Saint Alexander. This vertical symbolic progression from Evil toward Good reasserts the doctrine conveyed by the enamel decoration on the sides of the case". For the pilgrims coming to pray, most of whom would have been illiterate, both the relic and the reliquary served as a visual reinforcement of the power of God and Christianity in general.

Silver repoussé, gilt bronze, gems, pearls, and enamel - Musées Royaux d'Art et d'Historie, Brussels, Belgium

Notre Dame de Paris

The Notre Dame de Paris ("Our Lady of Paris"), one of the most recognizable cathedrals in the world (and the cathedral of the Catholic archdiocese of Paris, which houses the official chair -"cathedra" - of the Archbishop of Paris), is one of the French capital's most recognizable and visited landmarks, and an exemplar of French Gothic architecture. The towering cathedral had thinner and higher walls than the Romanesque buildings that preceded it, but these proved highly susceptible to stress fractures. Notre Dame is thought to be one of the first buildings in the world to incorporate flying buttresses (arched exterior supports) as a means of surmounting this problem. The long period of construction did, however, mean that the building, with its vast displays of artworks, sculpture, and stained glass, introduced emerging ("post-Gothic") styles such as naturalism.

The "first" art historian, the Italian Giorgio Vasari, dismissed Notre Dame as a "barbaric" insult to the austere Romanesque style of architecture that preceded it. It was not a view shared (some 400 years later) by the famous historian E H Gombrich, however. He wrote "the walls of these buildings were not cold or foreboding [as they were in the Romanesque style]. They were formed of stained glass that shone like rubies and emeralds. The pillars, ribs and tracery were glistening with gold. Everything that was heavy, earthy or humdrum was eliminated. The faithful who surrendered themselves to the contemplation of all this beauty could feel that they had come nearer to understanding the mysteries of a realm beyond the reach of matter". Gombrich concluded that the magnificent façade of Notre Dame "is so lucid and effortless in the arrangement of its porches and windows, so lithe and graceful the tracery of the gallery, that we forget the weight of this pile of stone and the whole structure seems to rise up before us like a mirage".

Paris, France

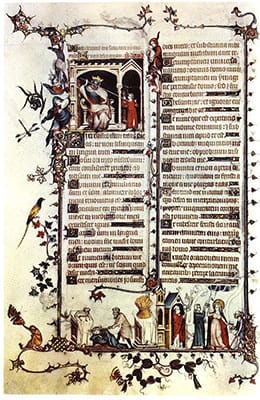

David before Saul, folio 24 verso of the Belleville Breviary

Jean Pucelle's Belleville Breviary was a religious book that contained the liturgy service for each day including psalms and scriptures to read, and prayers to recite, at specified hours. While the text was important as a devotional book, it was the illustrated artworks included on the pages that make it most impressive. As described by author Fred Kleiner, here Pucelle depicted, "his fully modeled figures in three-dimensional architectural settings rendered in convincing perspective. For example, [in the page seen here] he painted Saul as a weighty figure seated on a throne seen in three-quarter view, and he meticulously depicted the receding coffers of the barrel vault over the young David's head".

While illuminated manuscripts had been popular throughout the Middle Ages, it was during the Gothic period that the artworks reached new heights of sophistication. Book of Hours, or private devotional books such as this, were only able to be commissioned and owned by the most wealthy and important; in this case, the Queen of France Jeanne d'Evreux, wife of King Charles IV. The time, effort, and expense involved in the making of such a book reinforces the important role that art played in religious practice during the Gothic period. Moreover, the Old Testament story of David and Saul is set here in earthly surroundings bringing the earth and the heavens into concert. As Kleiner comments, the artist's "renditions of plants, a bird, butterflies, a dragonfly, a fish, a snail, and a monkey also reveal a keen interest in and close observation to the natural world".

Ink and tempera on vellum - Bibliothèque nationale de France, Paris, France

Peaceful Country

Built in the late Medieval period, the Palazzo Pubblico (1288-1309) in the Italian city of Siena, represents the architectural developments of this period which was marked by an increase in secular structures being built for government or civic use. This detailed wall fresco by Ambrogio Lorenzetti is part of a larger mural series titled Effects of Good Government in the City and in the Country. It features a countryside view of Siena including all four seasons of agricultural growth and development - from planting to harvesting - in one painting. Peasants are hard at work in the fields with their baskets overflowing with crops, while nobles look down on the scene from a hilltop. In the top left corner of the fresco a personification of security in the form of a winged female hovers, holding out a scroll on which words are written promising peace and security to all that follow the rule of law (which in Siena at this time was administrated by a group called the Nine). The heavy focus on the earth makes it one of the first examples in Western art of a dedicated landscape painting.

An important work of late Medieval art, the painting shows the growing value placed on secular themed art that was used to reinforce the validity of ruling powers and the need for individuals to be good, law abiding citizens. Quite literally, here there are words promising security for all who follow the law while the lush landscape, with an abundance of crops, reinforces the promise that all will be well for those who practice good citizenship. The work, and the others in the series which included similar sentiments, was commissioned for the government meeting room in the Palazzo Pubblico and the frescos covered three of the room's four walls. In this way, the fresco also served as a reminder of the responsibilities that the government had to protect its citizens. The notion of good citizenship was one of the many fundamental principles of the Humanist worldview that would come to underscore the looming Renaissance period.

Fresco - Palazzo Pubblico, Seina, Italy

Overview of Movement

Beginnings: The Birth of Religious Art and Late Antiquity

The birth of Medieval art can be traced back to the end of the Roman Empire and the move away in the third century from the belief in mythological gods (polytheism) in favor of the worship and adoration of a single God (monotheism). While Christians and Jews had been practicing their faith before this period, these groups could not worship openly without the fear of violent persecution. Those living under the reign of Emperor Nero (54 - 68 CE), for instance, were either subject to public executions, or used as fodder for baying Roman spectators in barbaric Colosseum games. Jews and Christians were thus forced to practice their faith in secret. Hidden in the back of homes, such as in Dura-Europos, a Roman border town (in present day Syria), for instance, one might find a hidden room or chamber filled with frescoes depicting religious narratives. Given the secrecy of such worship, much of the earliest art has been lost.

These religious restrictions were lifted by Roman Emperor Constantine, who ruled between 306 to 337, once he too became a follower of Christianity. Author Marilyn Stokstad writes, "First [Constantine] issued a decree whereby Christians would be tolerated and their confiscated property restored, then he recognized Christianity as a lawful religion". She adds that, in "a crucial pronouncement known as the Edict of Milan, issued in 313 in concert with the Eastern ruler, Licinius, Constantine formalized his earlier decrees. The text of the edict, a model of religious toleration, allowed not only to Christians, but to the adherents of every other religion the choice of following whatever form of worship they pleased".

Constantine's edict accordingly gave rise to an increase in religious-themed art. Mural paintings on the walls and ceilings of the catacombs featured narratives taken from the Christian faith. Religious funerary decorations were also popular, and while sculptural works were more limited, they could also be seen in relief carvings on burial sarcophagi. Another material for works of this period was ivory, with pieces carved of these animal tusks doubling as religious iconography and as a status of wealth.

While the art of Classical Antiquity produced figures of idealized physical beauty, the art of Late Antiquity - a period of transition between Classical Antiquity and the Middle Ages (spanning from the late 3rd century to the 7th or 8th century) - and the Medieval Period, relegated aesthetic excellence to a secondary position; ceding to the primary need for the viewer/worshipper to read the biblical parable without aesthetic distractions. Flat in form, Medieval figures lack detailed body modelling or dimensionality beneath their garments, and were typically represented without any sort of anchoring to the ground, giving them the appearance that they were floating. Hierarchical rules were also followed with the most important figures in the narrative depicted as taller and attired in more elaborate and colorful costumes.

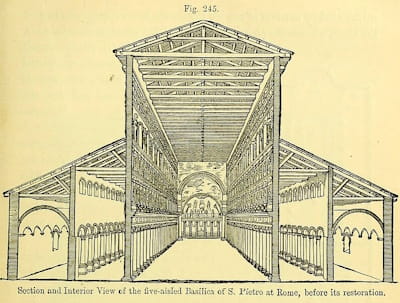

Constantine's rule also provided the catalyst for the building of large places for Christian worship. Architects of the period of Late Antiquity moved away from the traditional temple design and instead modified the secular basilica model used in government buildings. According to Stokstad, "in their churches, Christians adapted the basilica form to their own purposes. At the end of the hall a single apse housed the clergy and the altar, while the hall served the congregation. The entrance was placed opposite the apse so that, on entering, the worshipper's attention was immediately focused on the sanctuary". These somewhat basic structures were made worthy of God through their generous interior decoration. Constantine's administration oversaw the building several new churches, the most notable of which, Saint Peter's (c. 319), housed relics of the apostle (St. Peter). Another of Constantine's churches Santa Costanza (337-351) in Rome, was originally built as a mausoleum which was later converted to a church.

Early Byzantine Period (250-842 CE)

In 330, as part of his Eastern expansion, Emperor Constantine founded a new imperial city in Byzantium, naming it Constantinople in his honor. While the Western Empire would fall in 476, Byzantium continued to prosper. Many of the finest examples of early Byzantine art were produced under the rule of Emperor Justinian whose reign began in 527. A formidable military leader and conqueror, Justinian was also a great patron of the arts and did much to spread religious iconography throughout the expanding Eastern Roman Empire. Justinian had a special penchant for church building. In addition to the magnificent church of Holy Wisdom in Constantinople (better known today as the Hagia Sophia), he oversaw the building in 547 of another architectural masterpiece, the San Vitale in Ravenna, at that time the capital city of Byzantine Italy. With its striking octagonal structure, topped by a terra-cotta dome, the San Vitale's interior houses the exquisite fifteen mosaic medallions (featuring Jesus Christ and the Apostles) that adorn the triumphal arch.

This period is also closely associated with the production of religious icons. Author Fred Kleiner writes, "from the sixth century on, [icons] became enormously popular in Byzantine worship, both public and private. Eastern Christians considered icons a personal, intimate, and indispensable medium for spiritual transaction with holy figures. Some icons [even] came to be regarded as wonderworking, and believers ascribed miracles and healing powers to them". However, between 726 and 787, a group backed by Emperor Leo III, launched a campaign to destroy all icons in the belief that they had become objects of worship in-and-of themselves (rather than an aid to prayer) and were thus linked to the veneration of false idols. The "Iconoclasts" were Christian fundamentalists who adhered to a literal translation of the Ten Commandments which forbids the making and worship of graven images. A second period of iconoclasm followed between 814and 842, finally bringing the Early Byzantine period to an end.

Middle Byzantine Period (843-1203 CE)

In the period following Iconoclasm, the Byzantine empire was rejuvenated. As part of its new prosperity, Byzantine art and architecture underwent a series of changes. Churches of this period followed the style of Justinian's reign but on a much more modest scale. Art historian Evan Freeman writes, "Monumental depictions of Christ and the Virgin, biblical events, and an array of various saints adorned church interiors in both mosaics and frescoes. But Middle Byzantine churches largely exclude depictions of the flora and fauna of the natural world that often appeared in Early Byzantine mosaics, perhaps in response to accusations of idolatry during the Iconoclastic Controversy. In addition to these developments in architecture and monumental art, exquisite examples of manuscripts, cloisonné enamels, stonework, and ivory carving survive from this period as well".

![Bonaventura Berlinghieri, <i>Saint Francis of Assisi</i> (1235). The Italian Art Society states, “This image, which shows strong ties to Byzantine icons, [...] emphasizes Francis' humility and poverty as well as his special relationship to Jesus.”](/images20/photo/photo_medieval_art_5.jpg)

1054 saw the "Great Schism" between the Eastern Orthodox Byzantium Christians and the Western Roman Catholics (referred to locally as the "Latins" or "Franks"). In 1204, the Italian and French Fourth Crusade sacked Constantinople, destroying or looting many of the city's art treasures. The crusaders duly occupied Constantinople where they established a new "Latin Empire". Exiled Byzantine elders established three successor states: the Empires of Nicaea and Trebizond in Anatolia, and the Despotate of Epirus in Greece and Albania. In 1261, the Nicaeans regained control of Constantinople from where, under Emperor Michael VIII Palaiologos, they established the rule of the Palaiologan dynasty. The Crusade had created great enmity between eastern and western Christians, yet out of this conflict came a creative merging of Byzantium and Western European art. Freeman observes that this tendency was particularly evident "in Italian paintings of the late Medieval and early Renaissance periods, exemplified by new depictions of St. Francis painted in the so-called Italo-Byzantine style".

Late Byzantine Period (1261-1453 CE)

Following the recapture of Constantinople in 1261, the Byzantine Empire continued to reign until it fell to the Ottoman Turks in 1453. The art of this period would evolve in line with new ideas and tastes. Mosaics were still dominant in church decoration, but frescos became increasingly popular. This coincided with a shift in types of imagery with frescos more amenable to narrative scenes. These scenes carried a new sense of naturalism in the way the contours and movements of the human body were more discernible (under their clothing). Simple landscapes and pastoral settings became common, while architecture also began to be depicted. Buildings tended to be slightly skewed, but painters' awareness of architecture and perspective became more evident as the art evolved.

The 5th century Church of the Holy Saviour in Chora took its name from its location (Chora) just outside Constantinople's walls. Considered one of the great vestiges of the Late Byzantine art and architecture, the Chora's interior decorations, featuring a spectacular array of frescos and mosaics, were completed between 1315 and 1321 under the direction of the statesman, Theodore Metochites. He later enlarged the ground plan from the original small symmetrical church, into a large, asymmetrical square consisting of three areas: the inner and outer narthex or entrance hall; the naos or inner chapel; and the side chapel, known as the parecclesion (that originally doubled as a mortuary chapel housing eight tombs). The Chora's defining exterior feature consists of six domes, with concave bands originating from their centers. Viewed from the interior, the spaces between the domes' bands depict images of Christ and the Virgin flanked by angels or ancestors.

The Merovingians (481 - 751)

While the Eastern division of the Roman Empire thrived, the Western side fared less well. Military and political conflicts were commonplace and outside civilizations colonized large areas of the Empire. The Germanic tribe known as the Merovingians reigned from the 5th to the mid-6th century in an area that today is part of France. Early Merovingian art was small in stature and favored animal imagery. Items such as belt buckles, fibulae, or ornamental pins, and small medallions, were highly detailed and created in the decorative style of cloisonné. In this process, small pieces of metal are soldered in strips with the spaces between filled in with enamel, gemstones and pieces of glass. Several characteristics of these artworks were highly colorful, geometric patterns and interlocking abstracted animal forms.

Many Merovingians treasures have come from excavated burial sites. As was their custom, wealthy and important Merovingian lords were buried in ships filled with their treasures including jewelry, pottery, coins, and medallions. The greatest of the excavated ships was discovered in 1939 in a field in Suffolk, England, under what is now known as the Sutton Hoo burial mound. Treasures included a warrior helmet, weapons, belt buckles, and textiles. The British Museum says of the site, "the interment of a ship at Sutton Hoo represents the most impressive medieval grave to be discovered in Europe". The Merovingians were Christians and built their own churches, too. They copied the late Roman style of basilicas, such as in the Church of St. Martin of Tours, in Yeovil, Somerset, and filled the interior with paintings and other carved decorations. They also built monasteries where monks created highly decorative illuminated manuscripts, with many favoring animal motifs.

The Visigoths (410-716)

The Visigoths were the westerly division of the Goths; a Germanic people that invaded the Roman Empire from the east between the 3rd and 5th centuries. Christians, the Visigoths created a kingdom in areas that now belong to Spain, France, and the Iberian Peninsula (the eastern division of the Goths, the Ostrogoths, founded their kingdom in Italy). Art historian Kathleen Kuiper writes, "The [Visigoth] art produced during this period [5th-8th century] is largely the result of local Roman traditions combined with Byzantine influences. The effect of Germanic metalworking techniques is also seen in the decorative arts, but the ornamentation of these pieces, most notably a collection of jeweled crowns and crosses known as the treasure of Guarrazar [the site of an important archaeological site in Spain], owes nothing to the Germanic artistic traditions. Instead, plant and animal motifs from the Mediterranean and Eastern traditions are used".

The Visigoths were highly skilled in fine detailing and well known for their small metalwork pieces and jewelry which feature vibrantly colored gemstones and animal motifs, especially the eagle. The architecture of the Visigoths, meanwhile, was smaller in stature than some of the other early Medieval designs, but was distinguished through its fine masonry work. The church of San Juan Bautista, Baños de Cerrato (now in the province of Palencia, central Spain) was erected in 661 by the Visigothic king. Its features include horseshoe arches and square apses which were thought almost unique to the Visigoths at that time. A further characteristic of Visigoth churches were the ornamental sculptures that graced their simple basilican interiors.

The Vikings (793 - 1066)

Landing in Rome in 793, the Scandinavian Vikings were ruthless and brilliant military strategists who went on to conquer lands that are now part of Britain, Ireland, and France. With their great maritime skills, the Vikings dominated through the middle of the 11th century. The Vikings were great craftsmen and artisans with their iconic longboats used for both travel and funerals. The ships themselves were works of art, with the carved prow and stern often sculpted to resembling snaking sea beasts (some with human heads). Carvings of these ferocious firedrakes, and other types of animal motif, were also carved onto other forms of military transport and amulets.

Viking art favoured materials that could be carved or engraved, such as wood, metal, stone, ivory, and bone. The Vikings also produced pictorial textiles and wall tapestries, and jewelry in the form of brooches and pendants. Of the latter, art historian, Andrea C. Snow writes, "Many objects served practical and symbolic purposes and their complex decorative patterns can be a challenge to untangle. Highly-stylized motifs weave around and flow into one another, so that following a single form from one end to the other can be difficult - if there are end points at all. Imagery was created to communicate ideas about social relations, religious beliefs, and to recall a mythic past. Although many objects served pagan intentions, Christian themes began to intermingle with them as new ideas filtered into the region".

The Anglo-Saxons and Hiberno-Saxons (410 - 1066)

When the Romans left England around 410, factions and tribes fought for dominance of land, before the Angles and the Saxons - The Anglo-Saxons - arrived in England from Denmark, and took over control of vast areas of the country. Hibernian (Irish) monks arrived in England in 635 bringing with them ancient Celtic traditions. The Hiberno-Saxons is the name given thus to the melding of pagan Anglo-Saxon, and Christian Hibernian, cultures. The zoomorphic patterns and bright coloration favored by the Anglo-Saxons interlaced with the curvilinear forms, scrolls and spirals that was the Celtic tradition. This resulted in an elaborate decorative style with artisans employed to produce metal and ivory utilitarian objects dominated by carvings of abstract animal motifs. Hiberno-Saxon church building, meanwhile, is characterized by pilasters, blank arcading, baluster shafts and triangular-headed openings. While sculptures and large-scale artworks were rare, the Hiberno-Saxon High Cross, made of sandstone and finely carved with religious-themed reliefs, were regularly used to signpost monuments and memorials.

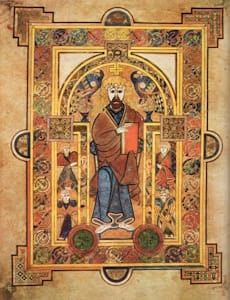

The Christian art that dominated the Medieval period is closely aligned with the production of illuminated manuscripts. Considered one of the greatest treasures of its kind, the Book of Kells was written on vellum (calfskin) pages in calligraphic Latin and features the four Gospels of the New Testament. The book was the work of three Celtic monks based in the Columban monastery on the island of Iona. However, following a deadly assault by Viking raiders, the monks took the book with them when they fled to the newly built monastery at Kells in County Meath, Ireland (where it was probably completed around 800). Historian Martha Kearney writes, "Practically all of the 680 pages are decorated in some way or another. On some pages every corner is filled with the most detailed and beautiful Celtic designs [...] There are many images of animals throughout [...] from exotic peacocks, lions and snakes to more domestic cats, hares and goats. There has been much research into their significance. Some like the goats were presumably part of everyday life but others could have been pagan symbols carried over into the Christian era".

Carolingian Art (800-900)

The Carolingian Empire began in 800, the year Pope Leo III made the King of the Franks, Charles the Great, the first emperor of the Western Roman Empire. It lasted about 100 years. Charlemagne, as he became better known, masterminded successful military campaigns across northern Europe, and launched an intellectual and cultural "golden age" known as the "Carolingian Renaissance" (named after the Carolingian dynasty from which Charlemagne was descended). Charlemagne filled his court with intellectuals and ministers who set about the task of extending the influence of Christianity throughout Europe. His administration launched many educational and cultural initiatives, including improving Latin literacy, inventing a new calligraphic script (Carolingian minuscule), and promoting new forms of art, poetry, and architecture. According to Kleiner, "the 'Carolingian Renaissance' was a remarkable historical phenomenon, an energetic, brilliant renovation of the art, culture, and political ideals of Early Christian Rome".

The Carolingian Renaissance featured a major new building campaign; one that sought to match the great masterpieces of the Classical architecture of the past. Kleiner writes, "For his models, Charlemagne looked to Rome and Ravenna. One was the former heart of the Roman Empire, which he wanted to renew. The other was the long-term western outpost of Byzantine might and splendor, which he wanted to emulate in his own capital at Aachen". Perhaps the greatest contribution to the architecture of the period was the tower structure, as exemplified in the mid-century with the consecration of the Abbey Church of St. Riquier in Corvey, Germany. It offered a much grander entranceway into a spacious church building where altars and even choirs could be stationed. This proved an important development as Carolingian churches were designed to house much larger groups of worshippers, many of whom had undertaken long pilgrimages to holy sites.

Ottonian Art (951-1024)

Following his death in 814, Charlemagne's empire began to slowly crumble. In 936 a dukedom in Saxony (northern Germany) came to power under the rule of Otto I, or Otto the Great, as he became known. Crowned king of Aachen by the pope in 962, the Ottonian Empire (Otto's reign was extended by his heirs, Otto II (r. 973-83) and Otto III (r. 983-1002)), restored the Holy Roman Empire throughout (what are now) Germany, Switzerland, and northern and central Italy. The Ottonians also fostered close ties with Byzantium. Independent scholar Jean Sorabella writes, "The Ottonian revival coincided with a period of growth and reform in the church, and monasteries produced much of the finest Ottonian art, including magnificent, illuminated manuscripts, churches, and monastic buildings and sumptuous luxury objects intended for church interiors and treasuries. Christian iconography predominated, but political imagery was often integrated with sacred scenes".

While there had been a gradual move towards realism and naturalism in Christian figures, Ottonian art is associated with a pronounced emotional depth. In works showing the crucifixion, for instance, Ottonian art was apt to emphasize the agony of Christ's suffering (whereas previously it had been nullified). Sculpture was becoming prevalent, too, with an increase in carved ivory reliefs, elaborate sculpted church doors, and a renewed passion for freestanding sculptures, such as the Gero Crucifix (970), that had not been seen since the age of Classical Antiquity. Ottonian architecture, meanwhile, incorporated many of the distinguishing features that came before it, including a preference for Carolingian westworks (the name given to a monumental western church front constructed in the form of a tower). Saint Michael's in Hildesheim, Germany, for instance, features two transepts, a grand westwork, and additional towers. These churches proved to be harbingers for the design of Romanesque churches.

Romanesque Art (1000-1150)

The Romanesque period began around 1000 and lasted until 1150 (when it evolved into the Gothic). It was the result of the expansion of monasticism, and with that expansion, the building of new churches throughout western Europe. The Romanesque blended stylistic elements borrowed from Roman, Carolingian, Ottonian, and Byzantine art and architecture. Romanesque Art became more realistic and more emotive. Religious themed illuminated manuscripts and mural paintings continued in earnest during the period, while painted icons and ornately-decorated reliquaries, or holders for holy relics, were also created and given prominence in Romanesque churches. The new churches served as key attractions for the thousands of people undertaking pilgrimages to holy sites throughout Europe.

Romanesque churches favored rounded stone arches which harkened back to early Roman architecture. The Romanesque also saw a return to monumental sculpture, with relief sculpture depicting biblical history adorning columns and their massive church doors. The interior walls and ceilings, meanwhile, were ornamented with frescoes depicting vignettes of Christ's life. Key features of Romanesque churches were vaulted stone ceilings, thick walls, and small windows. Towers were also a feature, as were decorative exterior design elements such as pointed and rounded windows. Pilgrimage churches, those which housed the most important relics, were newly built or expanded from their original structures to accommodate larger crowds and religious visitors.

Gothic Art (1150-1450)

The Gothic style covered the period between the 12th and 15th centuries. There were many artistic developments during this period. As Kleiner writes, "the great artistic innovations of the Gothic age were, as in the Romanesque period, made possible by the widespread prosperity and favorable climate that Europe enjoyed in the 12th and 13th centuries. This was a time of profound change in European society. The focus of both intellectual and religious life shifted definitively from monasteries in the countryside to rapidly expanding cities. In these new urban centers, prosperous merchants made their homes and formed guilds (professional associations)". Gothic architecture attempted to recreate a heavenly environment on earth. Gothic builders developed the use of flying buttresses (introduced to support the building's increased height and weight) and decorative tracery between stained glass windows thus creating interior spaces that dwarfed worshippers and dazzled their senses. Book arts also became a common feature of Gothic art with illuminated manuscripts and small books of prayers (books of hours) commissioned by wealthy patrons for private devotion. While many of the books were created by anonymous artisans, in France some individuals, such as Jean Fouquet, Master Honoré, and Jean Pucelle, began to gain recognition under the collective title: School of Paris.

Paris's iconic Notre-Dame Cathedral is generally agreed to be the definitive example of Gothic architecture. The church's move towards more ornate designs can be seen in the decorative rosette windows and pointed arches, and in the abundance of religious themed art that adorned the interior and exterior walls. While representations of Mary and the Christ child were popular throughout the Middle Ages, in many early depictions Christ is represented less as an infant and more like an adult of reduced size. In the sculpture Virgin of Paris (in Notre Dame) Mary and the Christ child are more natural (or childlike in Christ's case) thus representing a Gothic style that has moved away from the flat and simplified forms of religious iconography of the Late Antiquity, and the Byzantine periods, towards a more naturalistic and sensuous style. This feature is most notable here in the natural way in which Mary's body arches to support the weight of the child she rests on her hip. This natural parental posture would become commonplace during the late-Gothic period.

Late Medieval Art (1200-1400)

While the era of Medieval Art doesn't have a specific end date, it is generally agreed that it was signaled by the start of the Renaissance period. Nevertheless, the years between the end of the Gothic period and the birth of the Renaissance saw a maturity of many of the burgeoning concerns of the Middle Ages such as humanistic learning, naturalism, and individualism. According to Kleiner, "art historians debate whether the art of Italy between 1200 and 1400 is the last phase of medieval art or the beginning of the [Renaissance] of Greco-Roman naturalism. All agree, however, that these mark a major turning point in the history of Western art". Key artists of the period, such as Pisano, Cimabue, and Giotto, rendered religious works with an intense realism and a renewed interest in Classical art. These artists created figures that were fully dimensional and placed in settings that showed a greater sense of spatial depth, thereby pre-empting the work of Renaissance artists who would develop and master the art of linear perspective. Also gone was any need to differentiate the spiritual from the earthy, and in this period biblical scenes often incorporated landscapes as an important part of the narrative itself.

Another influence on the art of this period was the expansion of growing urban centers, such as in Italy which had been broken down into city-states with their own independent governments. Art of this period moved beyond solely religious themes to include secular themes, such as the works to encourage good government. Also popular were morality paintings that warned against sinful behavior. The architectural achievements of the Romanesque and Gothic periods continued in much of the church design during the Late Medieval period. One area of new development, however, was a more focused interest in civic buildings in which government activities could take place, such as Palazzo Pubblico, in Siena, and the Palazzo della Signoria, in Florence. With multiple floors and several individual rooms for various functions, these structures were also built with an eye to protect against invading enemies with towers or campaniles able to double as lookout posts.

Future Developments

The 19th century was witness to a growing interest in the art and culture of the "dark ages" with a growing impetus to record the period's significant legacy in the fields of art, craft, and architecture. This renewed pursuit can be largely accounted for through the maturation of art history as a serious academic discipline. Art historians looked to date surviving medieval artifacts and worked to piece together a timeline of the numerous, and many overlapping, styles that bridged this vast epoch. The heirs to these early histories have produced a story of art that shows us that the aesthetic vestiges of medieval art have a reach that far exceeds the dawning of the Renaissance age. As historians Simone Celine Marshall and Carole M. Cusack have noted, "The substantial medieval presence within the Modernist aesthetic is exemplified in moments of illumination that deploy religious and mystical traditions to orchestrate insights that are often secular, yet retain something of the religious intensity that brought them into being".

One can locate these traditions, for instance, in the English Arts and Crafts movement of the nineteenth/early twentieth centuries which demonstrated its debt to the splendour of the illuminated book through their own elaborately engraved printings and typefaces. One might cite, too, the German Die Brucke (The Bridge) group who were directly inspired by the raw woodblock prints of the Middle Ages, while in Russia, artists Natalia Goncharova and Mikhail Larionov collected folk textiles and prints, and studied Orthodox Christian icons, to create an aesthetic that was both modern and distinctly Russian. And in his book, Medieval Modern, Art out of Time (2012), Alexander Nagel demonstrates how medieval art has shaped the practice of pioneering modern artists as diverse as Constantin Brâncuși, Marcel Duchamp, Kurt Schwitters, and Robert Smithson. Today medieval art and artefacts is/are highly valued by museums and private collectors, while the era's central position in the timeline of art history provides inspiration for artists to whom the whole of art history is a source of inspiration.

Ask The Art Story AI

Ask The Art Story AI