Summary of The Pre-Raphaelites

The Pre-Raphaelites opposed the dominance of the British Royal Academy, which championed a narrow range of idealized or moral subjects and conventional definitions of beauty drawn from the early Italian Renaissance and Classical art. In contrast, the Pre-Raphaelites took inspiration from an earlier (pre-Raphaelite - before the artist Raphael) period, that is, the centuries preceding the High Renaissance. They believed painters before the Renaissance provided a model for depicting nature and the human body realistically, rather than idealistically, and that collective guilds of medieval craftspeople offered an alternative vision of artistic community to mid-19th-century academic approaches.

Key Ideas & Accomplishments

- The Pre-Raphaelites rejected not only the British Royal Academy's preference for Victorian subjects and styles, but also its teaching methods. They believed that rote learning had replaced truth and experience. Theirs was one of the first major challenges to "official" art, and their early "institutional critique" is a crucial piece of the history of modern art in Britain.

- Above all, Pre-Raphaelitism espoused Naturalism: the detailed study of nature by the artist and fidelity to its appearance, even when this risked showing ugliness. It also named a preference for natural forms as the basis for patterns and decoration that offered an antidote to the industrial designs of the machine age.

- As part of their reaction to the negative impact of industrialization, Pre-Raphaelites turned to the medieval period as a stylistic model and as an ideal for the synthesis of art and life in the applied arts. Their revival of medieval styles, stories, and methods of production greatly influenced the development of the Arts and Crafts and Art Nouveau design movements.

Overview of The Pre-Raphaelites

"Beauty without the beloved is like a sword through the heart," Dante Gabriel Rossetti wrote. His emphasis upon ideal female beauty made him a maverick among the Pre-Raphaelites.

Artworks and Artists of The Pre-Raphaelites

The Girlhood of Mary Virgin

This painting by Rossetti was the first Pre-Raphaelite work to appear in public. It featured the secretive initials "PRB," indicating that the artist was a member of the newly established Pre-Raphaelite Brotherhood. In the painting, the Virgin Mary appears at home with her mother, St. Anne, and an angel, while her father tends the garden outside the window.

The style is deliberately modeled on late Medieval and early Renaissance paintings, which were highly unpopular in Victorian England at the time. The composition defies the techniques of traditional perspective, with a notable flatness between the foreground and background, which foreshadows later artists' rejections of classical ways of depicting realistic space.

As art historian Jason Rosenfeld points out, "Rossetti's picture represents a revivalist style that draws on early Renaissance paintings from Northern Europe and Italy, blended with a comprehensive religious symbolism expressed in a profusion of clearly observed details and natural forms, such as the lilies redolent of the Virgin Mary's purity and the lamp evoking piety." Rossetti adds another touch of realism by portraying the likenesses of his mother and sister as Mary and Saint Anne; at the time this was considered blasphemous given the standard dependence on classical models for the Holy Family. Rossetti's daring combined with his Medievalist style was highly controversial and drew attention to the limits of the "Grand Manner" that was still celebrated in the British Academy. In effect, Rossetti was proposing a radical alternative way to represent even the most sacred of subjects.

Oil on canvas - Collection of the Tate, United Kingdom

Ecce Ancilla Domini! (The Annunciation)

Rossetti's painting of the Annunciation is still mystifying viewers in the 21st century. The angel Gabriel's announcement to the Virgin Mary of her impending miraculous pregnancy is one of the most familiar and popular subjects in religious art, but Rossetti's interpretation of the moment is utterly singular and was criticized for its realism when it was first exhibited.

Taking his inspiration from early Italian frescoes, like those by the monk Fra Angelico, Rossetti chose a simplified palette and composition. But within these self-imposed boundaries, and despite the inclusion of many recognizable symbols of the Virgin (the lilies, etc.), the scene departs totally from traditional depictions. The artist used his sister as a model for the Virgin, highlighting her red hair and the innocent, fragile state of a young woman just awakening from sleep. Since the Renaissance the Annunciation had been used as an example for women's piety and virginity, but the modern expression on Rossetti's Virgin's face and her posture seem disturbed and mysterious and are difficult to interpret as pious. This uncertainty introduced into a sacred scene is typical of Rossetti, and it is above all his Naturalism that allows the viewer to experience such a profound connection to the humanity of the normally idealized Virgin.

Oil on canvas - Collection of the Tate, United Kingdom

Ophelia

Ophelia is arguably both John Everett Millais' masterpiece and the most iconic work of the Pre-Raphaelite Brotherhood. Painted when he was only 22 years old, Millais worked for months in the open air in the countryside, composing the background with painstaking detail. In addition to flowers and boughs, Millais included reeds, the muddy bank, and a water rat.

Elizabeth Siddall, a cutlery-maker's daughter whose unusual looks were highly regarded by Pre-Raphaelite artists, modeled the figure of Ophelia, whose death is described in Shakespeare's Hamlet by Queen Gertrude. Ophelia, having gone mad from Hamlet's rejection, sinks slowly into the river while singing. Millais posed his model in a bathtub filled with water to accurately capture the effect of water on her clothes and hair. Famously, the model nearly died after the candles warming the water went out and she caught pneumonia. Well beyond earlier Victorian genre paintings, in Ophelia Millais strived to recreate a moment from a fictional work as it really happened, in a way that is highly realistic, while being simultaneously romantic and dramatic.

Oil on canvas - Collection of the Tate, United Kingdom

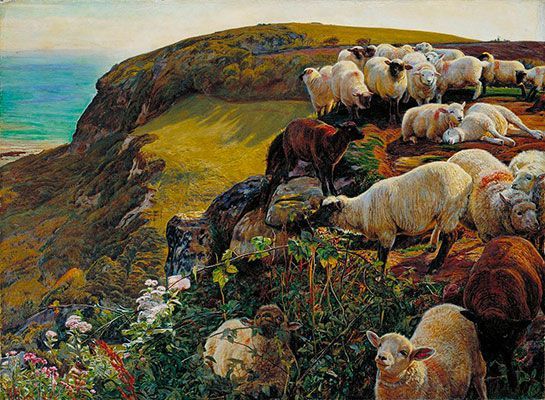

Our English Coasts (Strayed Sheep)

Landscape painting was an important expression of the Pre-Raphaelite commitment to nature and Hunt painted much of this scene outside, on the cliffs near Hastings. This pastoral painting was celebrated for its Naturalism: Hunt's special attention to the specific changing effects of light across a wide variety of surfaces (field, flower, wool, water, sky), all of which would have appeared extremely modern to the Royal Academy where it was first exhibited in 1853. In a bold departure from idealized scenes of the English countryside, the asymmetrical composition traps the lost sheep in a disorderly tangle of coastal vegetation.

The picture also carried a deep political significance. The cliffs of southern England face toward France and hint at the possibility of foreign invasion. For a populace nervous about Napoleon III's 1851 coup d'etat, Hunt's untended sheep, perched precariously on the cliff's edge, may have represented the vulnerability of the British nation and her coasts. Hunt further emphasizes this political reading of the landscape with the sheep's expressions; their appealing individuality draws the viewer's concern to their fate and the future of England. When the painting was exhibited at the Exposition Universelle in Paris in 1855, Hunt changed its name to Strayed Sheep, possibly to facilitate more neutral interpretations.

Oil on canvas - Collection of the Tate, United Kingdom

The Awakening Conscience

A key part of the original Pre-Raphaelite ideology was to subtly challenge basic tenets of Victorian morality. In The Awakening Conscience, Hunt portrays an unmarried woman in the role of a mistress. The artist clearly demonstrates her unmarried state by emphasizing her left hand, where a ring is missing from her fourth finger (and yet all other fingers have rings, a testament to the gifts of her lover). The painting expresses her moment of realization, as she rises from the lap of her lover with an enraptured expression, looking from the dark interior of the stuffy Victorian parlor to the beautiful sunlit garden outside (seen by the viewer in the mirror in the background). The discarded glove on the floor below her may symbolize the future (she realized) she faces.

In the bottom left corner, a cat has caught a bird, mirroring the gentleman and his mistress and indicating the trap he has prepared for her. Here, Hunt provides an unusual and controversial view of prostitution in Victorian England. As Tate curator Alison Smith argues, "Hunt was offering an alternative narrative to the downward trajectory through prostitution to the grave propagated in much of the contemporary literature surrounding the fallen woman."

The moral message of the painting is presented lightly, even ambivalently. The visual confusion of the room is heightened by her half-risen stance, which could be interpreted as sitting down rather than getting up. This ambiguous, seemingly sympathetic view of a common - but never publicly discussed - situation was a unique interpretation that encouraged viewers to question their judgments, rather than supplying them with simple moral formulas.

Oil on canvas - Collection of the Tate, United Kingdom

Light of the World

Like many first-generation Pre-Raphaelite religious pictures, Hunt's painting of Jesus from Revelation 3:20: "Behold, I stand at the door and knock..." faced fierce criticism when it was first exhibited at the Royal Academy in 1854. Although Hunt struggled greatly with the nighttime light effects, it was not the Naturalism that offended its initial audience; it was its largely unfamiliar religious iconography, which seemed worryingly Catholic - especially the ecclesiastical robes worn by Jesus.

After this critical reception, the painting was reproduced through engravings and other prints, and surprisingly, it became hugely popular with both Protestant and Catholic audiences. Almost fifty years later, Hunt was asked to paint another, larger version, that now hangs in St. Paul's Cathedral. Before it was donated to the cathedral by the businessman Charles Booth, it toured the British Empire for two years (1905-1907), drawing enormous crowds in Australia and South Africa (the Canadians weren't as impressed). Some scholars have suggested Booth saw a relationship between the Light of the World and the phrase "The sun never sets on the British Empire," linking the light of Christianity to the power and progress of the Empire.

One could make an argument that it was, for a time, the most famous painting in the world. It inspired endless copies, numerous Victorian poems, and even musical works, as well as being ubiquitous in Protestant religious publications. In an ironic, modern twist, Hunt was thus made world-famous by the industrial arts of popular culture that he spent a lifetime resisting.

Oil on canvas - Chapel at Keble College, Oxford

Lady Lilith

In the Judeo-Christian tradition, Lady Lilith refers to the apocryphal first wife of Adam, a mystical figure who is often closely associated with the serpent in the Garden of Eden. Although she appears in various narratives as a demon, murderess, and child abductor, the Pre-Raphaelites were probably most familiar with her Romantic description as a femme fatale in John Wolfgang von Goethe's poem Faust (1808). In the famous book Goethe tells how Lilith traps men with her "dangerous" long hair, lyrically conflating her locks with a serpent's deadly embrace. Rossetti and other artists were greatly drawn to this erotic symbol of the conflicted sexual politics of the Victorian period.

Although the Victorians are sometimes characterized as a sexually repressed society, recent scholarship has shown a much more complex reality where strict "official" codes of behavior are juxtaposed with an extraordinary wealth of Victorian sexual literature, art, and pornography. The representation of women as possibly dangerous sexual creatures can seem contradictory in a time when their public roles and educational opportunities were expanding. And it was this conflict that seems to have obsessed Rossetti in his female portraits, which so often feature powerful, seemingly self-possessed women with mesmerizing physical attributes. In the accompanying poem to this work (which echoes Faust), Rossetti writes that Lilith entraps Adam with "one strangling golden hair," thereby playing off unbound female hair as a Victorian symbol for the fallen woman. Likewise, an oversized comb draws attention to this act of self-beautification and enticement.

However, for all the apparent power granted to her by this gesture, Lilith is depicted as looking into a mirror and not at the viewer, allowing the (presumably male) onlooker visual access to her sexualized body, which is scaled larger than life and occupies nearly the entire canvas. She is powerful and frightening, but she is also safely contained within Rossetti's painting for the pleasure of male viewers: the temptress trapped.

Oil on canvas - Delaware Art Museum, Wilmington, Delaware, USA

Call, I Follow, I Follow, Let Me Die!

Julia Margaret Cameron was one of several photographers inspired by the Pre-Raphaelites. As a woman, Cameron worked with certain restrictions, but the new medium of photography allowed her great freedom to experiment in her home studio, and amongst her friends and relations.

In the mid-1860s, she worked on a series of close-up images of heads and faces, often of women among her household. This photograph is a portrait of her maid, Mary Hillier. Rejecting the conventions of stiff, formal Victorian photography, Cameron presents Mary as a sensual and free subject, with the Pre-Raphaelites' signature flowing hair and parted lips. She is dressed in simple clothing and set against a plain background, eliminating any telling narrative details in favor of an expressive focus. And in keeping with the poetic sensibility of the movement, the title of the photograph refers to a line spoken by one of the poet Lord Alfred Tennyson's tragic heroines: Eleanor, who dies of unrequited love for Sir Lancelot.

Cameron saw the work as a refusal of "mere conventional topographic photography - map-making and skeleton rendering of feature and form," which she saw in most photography at the time. Instead, she believed it was possible to use photography as an art form in its own right (akin to painting), a rare step that relates to the innovations the Pre-Raphaelites inspired in other non-fine arts media, including furniture and textiles.

Carbon print photograph - Victoria and Albert Museum, London

Laus Veneris

The painting's subject is taken from the German legend of Tannhauser, the story of a knight who is taken in by the Roman goddess of love, Venus, and encouraged to live a life of sensual indulgence. Eventually, Tannhauser sees the error of his ways and chooses to repent. In Laus Veneris (Worship of Venus), Burne-Jones represents a vignette of Venus relaxing in her luxurious bower with her handmaidens in a scene of subtle eroticism.

Pre-Raphaelite scholar Tim Barringer describes this work as "one of the most daring and powerful works in the Pre-Raphaelite canon. In this work, Burne-Jones collapsed the boundaries between the fine and decorative arts, and offered a complex rumination on the relationship between art, music and love." The painting's flat perspectival plane and sweeps of bold color evoke a decorative effect (the painting itself has the feel of a tapestry), and the many aspects of the composition (from the flowing fabrics of dresses to the elaborate scene behind Venus and the peacock feather fan) create a highly ornamental surface. This emphasis on an aesthetically pleasing and harmonious composition was a point of inspiration for the Aesthetic movement, which became popular in the 1880s.

Laus Veneris is closely related to a poem of the same title by the writer Algernon Swinburne, published in a volume dedicated to Burne-Jones. The artist used references to Swinburne's erotic stanzas such as "And I forgot fear and all weary things, / All ended prayers and perished thanksgivings, / Feeling her face with all her eager hair / Cleave to me, clinging as a fire that clings / To the body and to the raiment, burning them; / As after death I know that such-like flame / Shall cleave to me for ever; yea, what care, / Albeit I burn then, having felt the same?". He combined such lines with painterly, decorative surfaces that recall his work for Morris & Co. In doing so, Burne-Jones creates an image of female beauty and sensuality that is fundamentally modern.

Oil on canvas - Laing Art Gallery, Newcastle-upon-Tyne, UK

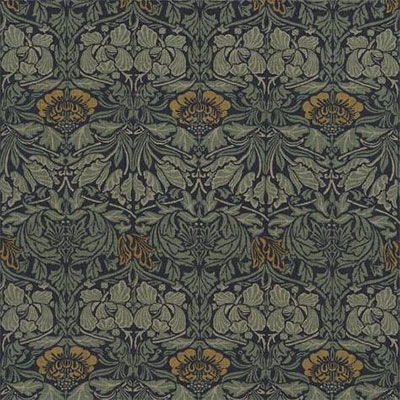

Kelmscott Manor Bed Hangings

In 1871, William Morris and Dante Gabriel Rossetti rented an Elizabethan house in the countryside together named Kelmscott Manor. Morris saw it as a place where he could fulfill his artistic and social ideals: living in harmony with nature and enjoying his work. He had an elaborate four-poster bed in the house, which he loved so much that he wrote a poem about it.

Morris's daughter May was a talented designer, seamstress and businesswoman, who ran the embroidery department of Morris, Marshall, Faulkner & Co. She created hangings for her father's bed and embroidered lines from Morris' poem onto them. The result is a unique combination of poetry, innovative design, and skillful craftwork that epitomizes her father's all-encompassing vision of Pre-Raphaelitism, and what makes a complete artwork.

Tate curator Alison Smith points out that "May was one of the leading craftworkers of the era, having developed an aptitude for embroidery during her girlhood that she supplemented by studying the technique at the South Kensington School of Design." May developed her own unique style of embroidery, inspired by her father and his love of nature, but with a freer hand and less rigidity of pattern. As with other Pre-Raphaelite furniture, the bed and its hangings were intended to be both art and a practical object. The hangings were displayed in an exhibition of arts and crafts production at a London gallery in 1893, confirming the late Pre-Raphaelite desire to incorporate art and beauty into every element of life.

Cotton, embroidery - Kelmscott Manor, Oxfordshire

Beginnings of The Pre-Raphaelites

Roots in Romanticism

The Pre-Raphaelite Movement grew out of several principal developments tied to Romanticism in early-19th-century Britain. The first was the reaction to industrialization, which had expanded at a feverish pace since the late-18th century, making Britain by far the most technologically and mechanically advanced nation by the 1830s. But with industrialization came an influx of laborers from the countryside who were crammed into dirty, polluted, and unsanitary housing and working conditions in the growing cities, where an increase in crime was also evident. Government regulation had failed to keep up with these rapid changes, and Romantic critics sought ways to expose such changes and ameliorate the situation. Artists and architects such as Augustus Welby Northmore Pugin, who was responsible for all the interior designs of the new Houses of Parliament (1836-60), advocated a return to the Gothic style and the supposed healthful, green, and moral environment of the medieval era, which they viewed as the antithesis of the industrial age. Pugin's Contrasts (1836) and The True Principles of Pointed or Christian Architecture (1841) proved enormously influential in promoting the Gothic Revival for the next several decades.

The Italian High Renaissance held a favored place in the British art world especially within the conservative Royal Academy. Founded in 1768, the Royal Academy was originally headed by the painter Joshua Reynolds, a great admirer of the High Renaissance, and especially the Italian Raphael. The Royal Academy championed genre and portrait painting (the latter of which was Reynolds' specialism) and encouraged artists to idealize their subjects in the dress and classicized surroundings reminiscent of ancient Greece and Rome, a tradition known as the Grand Manner.

During the 1840s, the newly established National Gallery in London acquired two "primitive" works that would help the reputation of early Renaissance art: the Arnolfini Portrait by Jan van Eyck (1434) and Lorenzo Monaco's San Benedetto Altarpiece (1407-9). The painting and the altarpiece are very different, but they share an extraordinary attention to detail and a preference for saturated color. The artists who would become the Pre-Raphaelites particularly admired Van Eyck's Arnolofini Portraitfor for its subtle symbolism, its renderings of natural light, and the intensely realized surfaces and textures.

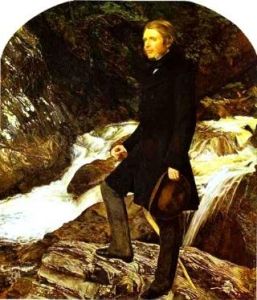

The reaction against the Grand Manner and classical ideals also manifested itself in Romantic painting and its emphasis on the landscape. The works of John Constable, Thomas Gainsborough, and J.M.W. Turner also proved highly effective in shifting attention away from ugly cityscapes. The Romantics offered a nostalgic portrait of the countryside and agricultural life (nostalgic, given that it was a lifestyle that was fast disappearing with the onset of industrialization) and the humbling power of nature over the human figure. Many of these works were associated with the idea of "the sublime," a term coined by Edmund Burke in his book, A Philosophical Enquiry into the Origin of our Ideas of the Sublime and Beautiful (1757), and which proposes that a sublime art would be able to draw out the strongest possible range of emotions in the spectator. The Romantics were championed by the influential art critic John Ruskin, whose work Modern Painters (1843/1846) defended Turner's originality (in particular), arguing that artists should devote themselves to the truths found in the observation of nature. Ruskin contrasted the "vulgarity" and "insipid repetition" of most academic painting with Turner's innovative Naturalism and light effects (Turner's paintings are often said to exemplify the idea of the sublime in art).

The Pre-Raphaelite Brotherhood

Inspired by these early Renaissance works, and by their disillusionment with the Royal Academy's prescriptive and idealistic approach to art, a group of young revolutionary thinkers - William Holman Hunt, John Everett Millais, and Dante Gabriel Rossetti - came together to create the secretive Pre-Raphaelite Brotherhood in September of 1848. Their aim was threefold: to revive British art; to make it as dynamic, powerful and creative as the late medieval and early Renaissance works created before the time of the Italian artist Raphael; and to find ways of expressing both nature and true emotions in art. The three original members were quickly joined by James Collinson and Frederic George Stephens (both painters), William Michael Rossetti (a poet and critic, and brother of Rossetti), and the sculptor Thomas Woolner. Although the impetus and fame of the movement remained with the three original founders, the term "Pre-Raphaelite" came to refer to any art made in the style popularized by the original trio.

The group's early doctrine - which emphasized the importance of each artist's own interpretation and agency - had four parts, as recorded by Dante Rossetti:

1. to have genuine ideas to express;

2. to study Nature attentively, so as to know how to express it;

3. to sympathize with what is direct and serious and heartfelt in previous art, to the exclusion of what is conventional and self-parading and learned by rote;

4. most indispensable of all, to produce thoroughly good pictures and statues.

The Pre-Raphaelites were also inspired by Ruskin's conclusions about "imaginative" modern painters who can "mark [...] the definite and characteristic leaf, blossom, seed, fracture, color, and inward anatomy of everything. [...] There is nothing within the limits of natural possibility that [the imaginative painter] dares not do, or that he allows the necessity of doing. The laws of nature he knows, are to him no restraint. They are his own nature." In a 1851 letter to the London Times, which marked the beginning of his involvement with the group, Ruskin stated that the Pre-Raphaelites "will draw either what they see, or what they suppose might have been the actual facts of the scene they desire to represent, irrespective of any conventional rules of picture-making." Ruskin continued his support for the Pre-Raphaelites until 1854, when his wife Effie asked for an annulment so that she might marry John Everett Millais.

The Breakup of The Brotherhood

Not only was Millais instrumental in repelling Ruskin's support, his own work led directly to the breakup of the Brotherhood. In 1850, Millais exhibited a new painting, Christ in the House of his Parents, which drew criticism from a number of circles, including author Charles Dickens, for blaspheming the Virgin Mary. Critics found Mary, whom Millais had modelled on his sister-in-law, "ugly," suggesting that it was scandalous to depict her as other than an idealized, beautiful woman, instead presenting the Holy Family as ordinary and poor.

In the aftermath of this controversy, James Collinson left the group, while the other members remained indecisive, and did not exhibit together again publicly. Woolner moved to Australia in 1852, and the final straw came in 1853 when Millais accepted membership to the Royal Academy - the very institution the Brotherhood had been challenging - prompting the group's official dissolution. However, while the original Brotherhood lasted no more than five years, the term "Pre-Raphaelite" stuck, and continued to be used in Britain for several decades.

Morris and Burne-Jones lead to Arts & Crafts Movement

In 1857, Dante Gabriel Rossetti met two of his young followers at Oxford: William Morris and Edward Burne-Jones. Burne-Jones became Rossetti's apprentice, and Rossetti invited the two friends to help him paint scenes from the life of King Arthur on the ceiling of the Oxford University Union. Between them, the three men promoted an even more rigorously medievalist strand of Pre-Raphaelitism, which espoused the virtues of a pre-industrial life and created paintings and furniture in the style of late medieval art.

Along with Rossetti, Morris and Burne-Jones began to formulate new directions for the Pre-Raphaelite movement. Morris in particular was keen to take the Pre-Raphaelite ideology beyond the realm of fine art, and ultimately founded the Arts and Crafts movement. Morris, with Burne-Jones, Rossetti and a few other associates, founded a new design firm called Morris, Marshall, Faulkner & Company. The company specialized in furniture, wallpaper, textiles, and stained glass based on medieval methods of handcraft and with illustrations drawn from Symbolist literature and poetry. Morris later bought out his other partners and renamed the firm simply Morris & Co. in 1875. The company thrived during the 1880s and 1890s, but eventually folded in 1940.

Pre-Raphaelitism Beyond The Brotherhood

Over the next two or three decades, more artists became associated with Pre-Raphaelitism. Many were painters, but there were also innovative sculptors and photographers who contributed to the progress of the movement. Ford Madox Brown was one of the painters who declined to officially join the Brotherhood but remained, nonetheless, closely connected to its members. He shared the Brotherhood's interest in Naturalism, poetry, and literature, but his explicit critique of Victorian society set him apart from most of the other artists. He had helped found Morris, Marshall, Faulkner & Co., and his daughter Lucy (also an artist) married William Michael Rossetti. The painter Arthur Hughes, meanwhile, had met Millais and Hunt early in the Brotherhood years but was not directly associated with the circle until he assisted with the Oxford Union murals. Hughes's work is in fact most emblematic of an "Arthurian" branch of Pre-Raphaelitism that focused specifically on the myths and stories of medieval England.

Several recent exhibitions have explored the relationship between Pre-Raphaelitism and early British fine art photography. Photographers including Roger Fenton, Julia Margaret Cameron, and Henry Peach Robinson were evidently influenced by the Pre-Raphaelites. These early innovators pushed the camera's mechanical representation of nature toward the fine arts and painting. The artists and photographers were often friends and took inspiration from the same literature, medievalism in costume and decoration; and a preoccupation with rendering light and natural detail.

A further shift in the broadening Pre-Raphaelite circle was toward portraits of women. From the late 1860s a number of artists, including Burne-Jones, Madox Brown, and Dante Gabriel Rossetti, began painting a series of beautiful, often sexually empowered, women. They used models most of whom challenged traditional Victorian standards of beauty. Many of the models were artists in their own right, including Georgiana Burne-Jones, Marie Spartali-Stilman, and Dante Gabriel Rossetti's favorite model, Jane Morris, the wife of William Morris and a skilled embroiderer (and with whom he had a well-publicized affair).

The Pre-Raphaelites: Concepts, Styles, and Trends

Truth to Nature

One of the earliest Pre-Raphaelite goals was to achieve the highest degree of objectivity in their depictions of nature. Millais and Hunt, for example, spent considerable periods of time away from London in the countryside, carefully studying plants and flowers in preparation for their paintings, including Millais' famous Ophelia (1851-2) and Hunt's Our English Coasts (Strayed Sheep) (1852). The preference for an unvarnished, honest aesthetic brought a sense of realism to mythical narrative already familiar to their audiences. For example, Millais's Christ in the House of his Parents features St. Anne's painfully swollen, elderly hands, a detail that British academic painting would softened so as not to offend public tastes.

Medievalism

The interest in late medieval and early Renaissance art from Italy and northern Europe was extended by Rossetti, Morris, and Burne-Jones, who also delved into the legends of medieval England. Their love of medieval craftsmanship was partly inspired by the suggestion, put so eloquently by John Ruskin in his essay "The Nature of Gothic" (1853), that the individual creativity enjoyed by medieval craftsmen was preferable to the "slavery" inherent in the modern industrial system. His argument had a profound effect on William Morris who set out upon a utopian mission to create a world where pre-industrial values and methods were restored. Morris's company specifically emphasized the use of labor-intensive handcrafts and a return to natural materials and dyes. In the same ideological vein, Burne-Jones designed tapestries that revived the arts of embroidery and weaving for a new generation.

Literature and Art

Several Pre-Raphaelite artists were prolific poets and writers. Dante Gabriel Rossetti frequently wrote sonnets to accompany his paintings, which he had inscribed on the frame, including the famous Lady Lilith (1868). Many Pre-Raphaelite artists also took works of literature as their source material drawing particularly on the writings of Robert Browning, Alfred Lord Tennyson, and William Shakespeare.

A key innovation amongst Pre-Raphaelites was to treat scenes from literature without romantic embellishments or crude stereotyping. Millais' Mariana (1851), for example, takes its title and subject from a character in Tennyson's poem of the same name (the poet was inspired by the character from Shakespeare's The Tempest). Rather than depicting Mariana waiting patiently and forlornly for her lover's return, Millais paints her in the process of stretching her back and looking bored with her wait. Morris, meanwhile, was an accomplished and widely published poet, who, in 1892, was offered the post of Poet Laureate of Great Britain (though he turned the offer down). In turn, many poets were influenced by Pre-Raphaelitism, most notably perhaps, William Butler Yeats and Oscar Wilde.

Decorative Arts

Although Pre-Raphaelitism is most readily associated with painting, the movement had a profound effect on the decorative arts. William Morris was at the forefront of a revolution in design that led eventually to the founding of the Arts and Crafts movement. Morris's company, Morris & Co., was intended to make good design available to a wider range of individuals (although the prices of his hand-printed and embroidered goods meant they were still generally restricted to the upper middle classes). Other artists, such as Burne-Jones and Dante Rossetti, joined Morris's efforts, producing designs and decoration for furniture and tapestries.

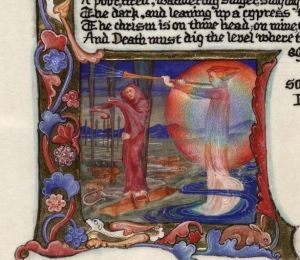

Moreover, Pre-Raphaelitism inspired a generation of illustrators including the artist Phoebe Traquair and the iconic Art Nouveau designer Aubrey Beardsley. Their hybrid styles mixed elements of Pre-Raphaelitism with other related movements. When Traquair illustrated famed Victorian poet Elizabeth Barrett Browning's Sonnets from the Portuguese, for instance, she combined the style of medieval illuminated manuscript, with watercolor paintings on vellum, and decorative motifs borrowed from 14th-century European manuscripts. Although Traquair had been directly influenced by the writings of the Pre-Raphaelites - even embedding the names of Ruskin and Rossetti in her murals for the Edinburgh children's hospital in 1885 - her illuminations also reflect her interest in Celtic and Byzantine arts.

Socialism and The Transformation of Society

In 1848, the year that the Pre-Raphaelite Brotherhood was founded, Marx's Communist Manifesto was published in London and revolutions broke out across Europe, largely driven by the middle and working classes and demands for democratic reforms. In this context, Pre-Raphaelite interest in medievalism and Naturalism, when set in opposition to the "progress" of industrial society, had unavoidable political implications. Although most of the Pre-Raphaelites were only tenuously associated with socialism, it is tempting to read, for example, a certain challenge to traditional class hierarchy in Millais' Christ in the House of His Parents, particularly when Charles Dickens condemned the artist's realistic portrayal of an impoverished Virgin Mary as "a monster in the vilest cabaret in France or in the lowest gin-shop in England." However, contemporary social and class conflicts are visible in a few of the Pre-Raphaelite's works, including one in Madox Brown's painting Work (1852-65). The Pre-Raphaelite belief that art could alter society gathered strength and developed its full expression in the Arts and Crafts movement, whose mission was clearly articulated by William Morris in socialist terms - to transform the lives of the working classes through arts and design.

Later Developments - After The Pre-Raphaelites

The Pre-Raphaelites became closely associated with the Aesthetic and the Decadent movements that emerged as early as the 1870s. Both moved away from the movement's original ideals of being true to nature and representation of non-idealized subjects. Rather, the Aesthetic movement privileged pleasing compositions over content. Several artists, most notably Edward Burne-Jones, began to paint in the Aesthetic style, producing sensual works designed to evoke bodily response in the viewer.

The Aesthetic Movement incorporated much of the Pre-Raphaelite influence on the decorative arts. Supplied with furniture from Morris & Co. and printed fabrics from Liberty's (a London department store that opened in 1875,) "aesthetes" were able to live as if they were inside a Pre-Raphaelite painting. Even the features of models made famous by Pre-Raphaelite portraits, which had been unfashionable when the movement began, had become the key markers for female attractiveness by the end of the nineteenth century. Rather than petite, plump, and fair, women aspired to be thin, large-featured, and red or black haired, echoing the portraits of Elizabeth Siddall and Jane Morris by Dante Gabriel Rossetti.

Throughout much of the 20th century Pre-Raphaelite contributions were rarely discussed and the movement, like much of Victorian art, was considered passé. There were some notable exceptions, including Salvador Dalí, who praised the Pre-Raphaelites' paintings of women as "carnal fantasies," and the "gelatinous meat of the most guilty of sentimental dreams." Despite sustained British interest in the movement, international exhibitions of Pre-Raphaelite art remained rare until the 1990s, when interest was revived in Pre-Raphaelite artists as individuals and as a group. These exhibitions challenged the idea of Pre-Raphaelitism as an insular and solely British movement, providing a template for re-examining the Pre-Raphaelite legacy in the history of modern art.

Useful Resources on The Pre-Raphaelites

- The Art of the Pre-RaphaelitesOur PickBy Elizabeth Prettejohn

- The Pre-Raphaelites: From Rossetti to RuskinEdited by Dinah Roe

- Painting with Light: Art and Photography from the Pre-Raphaelite to the Modern AgeEdited by Carol Jacobi and Hope Kingsley

- Reading the Pre-Raphaelites - Revised EditionBy Tim Barringer

- Pre-Raphaelites: Victorian Art and DesignBy Tim Barringer

- Pre-Raphaelites: Victorian Avant GardeOur PickBy Tim Barringer

- The Pre-Raphaelite SisterhoodBy Jan Marsh

Ask The Art Story AI

Ask The Art Story AI