Summary of Precisionism

Images of factories, skyscrapers, bridges, road and rail networks, steel works, and rural scenes featuring grain elevators and depots, were the order of the day for the Precisionists. Though it never published a manifesto, or even defined itself as a coordinated "movement", this loose-knit group of American modernists were united in their vision for a truly home-grown American art. Showing a collective preference for the simplified geometric forms associated with Cubism, Futurism and Orphism, and borrowing from the sharp focus and tight cropping techniques being pioneered by America's leading art photographers, the Precisionists marked the dawning of America's brave new industrial and scientific age through a language of coolly detached semi-abstraction.

Key Ideas & Accomplishments

- Precisionists represented their industrial American landscapes with a modern dynamism. Through their willingness to adopt strong contrast in color as a means of highlighting volumes and planes (in a way that the likes of Picasso and Braque did not), artists were able to present to the world a confident and optimistic vision of the dawning of this new era in American art and society.

- Precisionism has been describes a "cool art" in the sense that it established an objective distance between the work of art and the viewer. Precisionist artists, who passed over scenes of individual human activity, were connected through a "cool" level of detachment whereby the artist in question rendered their man-made environments through a combination of smooth brushwork and geometric precision. For these artists, images of modern America had no need for gratuitous embellishments.

- Analysts of a more pessimistic persuasion, have picked up on the absence of human figures in Precisionist works and interpreted this as a critique of the dehumanizing effects of the new age. But Precisionism was seen much more widely as a celebration of America's industrial and scientific prowess. Precisionism was not, then, a movement driven by social concerns but one that prioritized over everything else a tight rapport between a modern content and a modern style. In this respect, one can say that it pre-empted the global dominance of Abstract Expressionism.

- Precisionists tended to focus on urban subjects. But figures such as George Ault, Sanford Ross, and indeed Sheeler, applied the same approach to pastoral subjects, painting starkly geometric barns, grain elevators, cottages, country roads, and farmhouses. Subjects were chosen for the clean geometry and line of their formal qualities. On entering a Shaker meeting house, for instance, Sheeler enthused "No embellishment meets the eye" and reasoned that "Beauty of line and proportion through excellence of craftsmanship [would] make the absence of ornament in no way an omission".

- Although artists such as Morton Schamberg gravitated towards technological imagery, these objects would often be removed from their industrial setting and reduced to their raw components. Thus, the objects were transformed into an amorphous images that very often bordered on pure abstraction. Though historians have made comparisons between these pieces and those by the likes of Marcel Duchamp and Francis Picabia, Precisionist works tended to be more sincere, or less playful and ironic, that those of their European elders.

Overview of Precisionism

"Every age manifests itself by some external evidence", declared painter and photographer Charles Sheeler. "In a period such as ours", he continued, "when only a comparatively few individuals seem to be given to religion, some form other than the Gothic cathedral must be found", and it is the American factory that will be "our substitute for religious expression".

Artworks and Artists of Precisionism

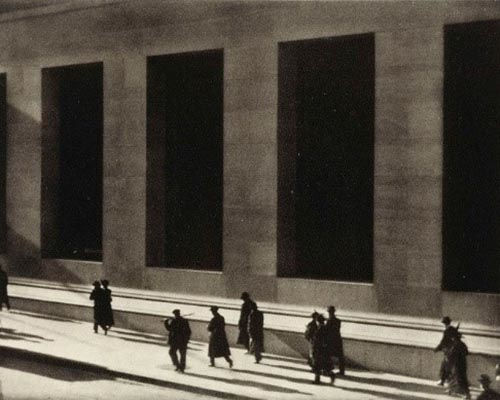

Wall Street

Wall Street is amongst the most iconic American images of the early twentieth century. It marked a clear departure for Strand, away from a style of photographic Pictorialism whereby the photographer used a camera and dark-room manipulation to produce soft-focus images that mimicked the Pictorialist style of painting. The image is an early example of Strand's move into documentary realism and abstraction, which he often incorporated within the same frame. On the one hand, Strand offers the spectator an objective - or "Straight" - record of a street scene showing walking commuters; on the other, we have a high-contrast interplay of light and dark as the shadows formed by the niches of the large Morgan Trust Bank building produce a sloping geometric pattern.

The geometric solidity of the imposing, temple-like building dwarfs the silhouetted figures who become anonymous - shapes stretched through elongated shadows. Strand was encouraged by the influential photographer and gallery owner Alfred Stieglitz to emphasise contrast, clean lines, and patterns in his works. Precisionist painters, who were also mentored by Stieglitz, were inspired by Strand's approach, reducing forms to their underlying geometry, and copying the camera's ability to crop in closely on compositions and reveal objectively the essence or core of ordinary objects and everyday scenes. Georgia O'Keeffe (to whom Strand sent love letters before she married his friend Stieglitz), in particular, shared in Strand's search for abstraction through close-up images of natural forms, but believed that painting could express something beyond the limits of the (mechanical) camera. It is said that Edward Hopper became fascinated with this image, and adopted some of the same formal techniques for his own paintings.

Platinum palladium print photograph - Whitney Museum of American Art

Painting VI (Camera Flashlight, Machine Still Life)

In the two or three years before his untimely death (aged 37, in the 1918 flu pandemic) Schamberg painted a series of objects sourced from illustrations in machinery catalogues (borrowed from his brother-in-law who worked for a hosiery company). Having died so prematurely, his position in the Precisionist movement is one of a forefather, who exerted especial influence over artists such as Charles Sheeler and Charles Demuth, both of whom explored mechanical themes in their painting.

Born in 1881 in Philadelphia, Schamberg qualified as an architect before enrolling as a post-graduate student at the Pennsylvania Academy of the Fine Arts (PAFA) where he studied under the impressionist William Merritt Chase. Following his time at the PAFA, he undertook several tours of Europe, sometimes accompanied by Chase and Sheeler. In Europe he confirmed his appreciation for the Old Masters but also encountered the works of modernists for the first time. As the auction house Sotheby's described it, while in Paris "He came to appreciate the underlying geometry he saw in compositions by Pablo Picasso and Paul Cézanne, as well as Henri Matisse's use of vivid, non-associative color [and his] immersion with these modes of visual expression proved deeply influential". Sotheby's adds that although Schamberg "did not fully abandon realistic subject matter, the works he created upon his return to the United States display[ed] a new concern for the structural rather than the representational function of color and he increasingly flattened and fragmented forms".

Referring to Painting VI, Sotheby's suggests that "Although the object is undoubtedly industrial in nature, Schamberg's reductive treatment makes it difficult to immediately identify and for many years it was incorrectly identified as a 'camera flashlight.' Indeed, the artist simplifies the components of the object to their most basic, geometric forms and places the machine in an amorphous setting, dissociating it from the larger context of the factory. As Schamberg's subject approaches abstraction he invites the viewer to consider it not for its function, but rather for its distinctive shape, color and form". Citing the art historian Wilford W. Scott, Sotheby's explains that the "imagery of the painting invites comparisons with the work of Marcel Duchamp and Francis Picabia, who similarly utilized the machine as subject matter in this period". Scott argues, however, that Schamberg "never subscribed to the satirical undertones embedded in the work of these artists" and that his formal approach avoided the "typical 'Dada' subversion of traditional art and meaning [and that in] discovering a new subject for his formal analysis, Schamberg transformed machines from objects of Dada irony and wit into objects of beauty".

Brooklyn Bridge

Following his showing at the influential Armory Show in 1913, where he exhibited a Futurist-inspired painting of Coney Island, Stella, an Italian immigrant, emerged as a key figure in the New York art scene. It is often argued that his images of New York, and especially the many he made of the Brooklyn Bridge - what he called "the shrine containing all the efforts of the new civilization of America" - were captured with an element of religiosity. Most critics and historians are in agreement that his paintings probably achieved their extraordinary power because they were viewed through the eyes of an "outsider".

Stella first painted the bridge in 1918 and returned to it repeatedly throughout his career. Rather than capturing the structure literally, Stella presents a fractured, color-saturated, Cubist/Futurist evocation of a technological wonder, an almost mystical response to its wires and cables, walkways and tunnels, arches and granite piers - all of it re-configured into a transcendent image reminiscent of a Gothic cathedral, a Renaissance altarpiece or a stained glass window. By melding contemporary progress with historical allusions, Brooklyn Bridge became for Stella a symbol of progress and human achievement. "I felt deeply moved," he said of it, "as if on the threshold of a new religion or in the presence of a new DIVINITY". The Whitney Museum of American Art added that "By combining contemporary architecture and historical allusions, Stella transformed the Brooklyn Bridge into a twentieth-century symbol of divinity, the quintessence of modern life and the Machine Age".

Oil on canvas - Yale University Art Gallery

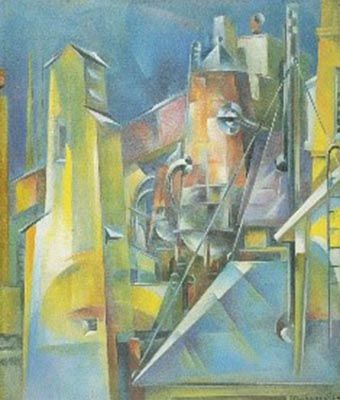

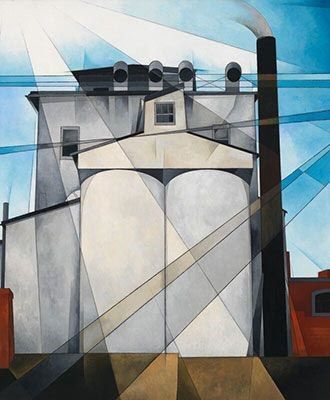

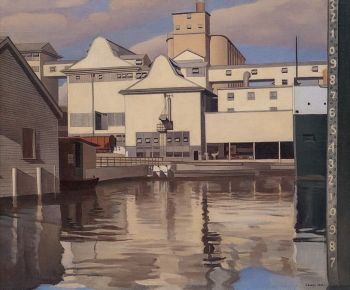

Factory

Dickinson had lived in Paris between 1910 and 1914, becoming conversant with the works of Cézanne and the Cubists. Upon his return to New York, he became affiliated with the progressive Charles Daniel Gallery where he exhibited alongside Sheeler and Demuth. He had initially painted urban scenes using a flat, decorative style but, by 1918, he modified his style to better represent images of industrial factories and grain elevators. It was on the basis of such subject matter that Dickinson has been associated with the Precisionists, although he remained something of an individualistic voice. The New York Sun wrote in 1927 that Dickinson had "won an enviable position among contemporary painters" but the critical response to his work remained mixed.

His Factory is a quasi-Cubist breakdown of tensely strung diagonal lines, fragmented shapes and gleaming colors, that capture the dynamism of industry and the sheen of its metal. But as with many of his paintings, Dickinson's mechanised landscape is imaginary; an idealised and romanticized view of the benefits of machinery for human advancement. He was, however, one of the first American artists to depict such subject matter and was working in what would soon be known as the Precisionist style as early as 1915. His Precisionist images, which predate even those of Charles Sheeler and Charles Demuth, combined, according to curator Gail Stavitsky, "technical precision and intellectual force to a degree hardly approached by any of his companions".

According to art historian and curator Ruth Cloudman, Dickinson began a series of "hard" industrial scenes around 1918 and these were "a logical outgrowth of his earlier urban views that contained small industrial vignettes" but which shared with his larger industrial subjects the "energetic brushwork and what has been described as a Cezannesque 'glitter of faceted planes'". The Factory, she continued, is "the result of several factors: freer brushwork, a greater reliance on diagonals and oblique perspective, a dramatic interplay of bright light and shadow and the implied movement of smoke and steam". Cloudman adds that Dickinson "draws the viewer toward the center of activity in contrast to the earlier scenes in which the observer had a more distant viewpoint" and that in these later works "Light assumes increasing importance creating lively surface patterns, highlighting volumes, and faceting forms" and that "For the most part the industrial views are colorfully painted with little, or no, reference to actuality". Dickinson died from pneumonia in 1930 at the age of 41 after a long battle with alcoholism.

Oil on canvas - Columbus Museum of Art

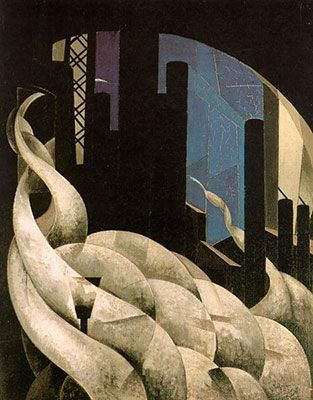

Incense of a New Church

In his early years, Demuth worked primarily in watercolor, producing luminous images of flowers, circuses and café scenes. But, as the historian Janet M. Torpy notes, "after about 1916, the pretty, soft, and naturalistic paintings of the flora found in his mother's garden began to yield to the harder-edged, geometric, tension-filled executions of man-made subjects". In what Torpy calls "a paean of the Precisionist style", Demuth paints Lukens Steel Yard in Coatesville, Pennsylvania. He depicts smoke billowing and circling gracefully around the ominous, vertical chimneys which are highlighted against cartoon-like patches of sky. The combination of curves and geometric forms endows the image with a Futurist feeling of the motion and dynamism of the modern city, even though the smoke itself, is expressed through solidified, Cubist-like, grey patchwork.

As a child, Demuth saw Lancaster's Evangelical Lutheran Church of the Holy Trinity from his bedroom window, and the painting charts the factory town's shift from a landscape dominated by churches to one dominated by industry. The title of the work leads one to the work's meaning, though it is not clear if Demuth was expressing any kind of critique on an increasingly secular American society. In any case, the plumes of smoke represent incense, while the factory has supplanted the church as the dominant feature of the urban landscape.

Oil on canvas - Columbus Museum of Art

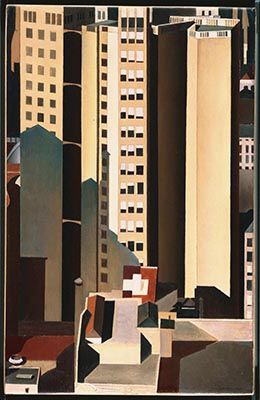

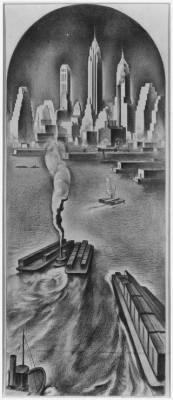

Skyscrapers

Sheeler underwent a process of artistic renaissance when, having studied under the American Impressionist William Merritt Chase, he traveled to France and Italy in 1908-1909. On his return to his home in Philadelphia he abandoned the carefree Impressionist style and started to experiment with the revolutionary Cubist techniques he had seen in works of Cézanne, Braque, and Picasso. Sheeler moved to New York in 1919, following the death of his close friend Morton Schamberg and it was here that he turned his attentions to the great icon of modern America: the skyscraper. Sheeler's interest in the city's landscape was confirmed through his collaboration with the photographer Paul Strand on the 1920 short film Manhatta which, regarded by many as the first American avant-garde film, emphasized the abstract qualities of the great metropolis.

Sheeler prepared this view from the Equitable Building, located at 120 Broadway in New York, with preliminary photographs and sketches, allowing him to capture the view with precision and detail. Planes of solid color draw the viewer's eye to the diagonal intersection of light and shadow toward the lower center of, what is arguably, Sheeler's most accomplished Precisionist work. Though no residents are shown, the differing heights of the blinds in each window suggests the presence of life inside the concrete towers. With its sharply defined geometric contours planes, and evocation of intense, direct, light the composition epitomizes Sheeler's Precisionist aesthetics. Of all the artists who are encompassed by the label, Sheeler epitomised the Precisionist movement. As professor Merrill Schleier put it, Sheeler was the "quintessential optimist of the urban scene [his] city views convey perfection, all ills ameliorated by the mechanical precision of the skyscraper".

Oil on canvas - Phillips Collection

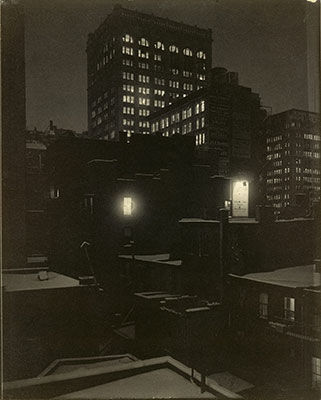

New York Street with Moon

O'Keeffe is one of the most significant American artists of the first half of the twentieth century. Classically trained in Chicago and New York, she fell under the influence of the progressive teachings of Arthur Westley Dow who encouraged his students to experiment with abstraction. While on a teaching posting in Texas she produced a series of abstract charcoal drawings which found their way via a friend to Stieglitz (her future husband) who put on her first exhibition at the 291 Gallery in 1916. By the time she produced New York Street with Moon, she was already recognized, primarily for her famous flower series of paintings, as one of America's most important modern artists.

The art historian Gail Levin noted that New York Street with Moon was O'Keeffe's first painting of New York which she produced while living in adjoining rooms on the 30th floor of the Shelton on Lexington Avenue: "I had never lived up so high before and was so excited that I began talking about trying to paint New York", the artist recalled later. "One can't paint New York as it is, but rather as it is felt", she said, and after her flowers series, her New York paintings would become her second major thematic group of the 1920s. In their simplified, geometrically-reduced forms, clear lines and smooth, polished, surfaces they conform to the Precisionist painters' objective approach to the city. Further, by taking a street-level view, O'Keeffe pays homage to the towering dimension of New York while the flattened planes of the buildings' facades, offset here by the red and white orbs of the city's street/traffic lighting, lends the work a quality reminiscent of stage scenery.

Levin writes, "O'Keeffe had hoped to show New York Street with Moon in Seven Americans, a show that [...] Stieglitz organised at the Anderson Galleries in 1925. However, Stieglitz pointed out to her that even men found it difficult to paint New York skyscrapers and refused to allow her to show this picture, preferring instead to exhibit her more feminine, large-scale flower paintings". Levin adds, however, that in her own show at The Intimate Gallery in 1926, "she insisted that Stieglitz hang this picture, which sold the first day for $1, 200. She beamed: "From then on they let me paint New York". Of the works themselves - which include titles such as City Night, (1926) Radiator Building-Night, New York (1927) and New York Night (1929) - Levin observes that O'Keeffe "seems to have preferred the mystery of nocturnal scenes rather than the raking sunlight she loved for flowers and other rural architectural subjects" and that by the end of the decade she had shown "that it did not take a man to deal effectively with the structures of the city [and duly] turned her focus elsewhere" (in northern New Mexico).

Oil on canvas - Museo Nacional Thyssen-Bornemisza

My Egypt

This enigmatic painting, one of seven in Demuth's final major series, depicts a concrete and steel grain elevator in Lancaster, Pennsylvania. The massive structure looms over the smaller, red buildings nearby - perhaps barns or family homes - almost barging them out to the sides and corners of the canvas. Several intersecting beams of light illuminate the grain elevator like an actor on a stage, and reiterating perhaps its importance while adding a Cubist-like fracturing of the composition.

The painting has been interpreted as both a critique of modernization and a celebration of it. The title suggests that industrialization is a pinnacle of American achievement equivalent to the great monuments of the ancient world. It helps evoke the great pyramids (of Egypt) and their symbolic association with life after death; no doubt a compelling theme for Demuth who, as a sufferer (and Guinea-pig for experimental treatments) of early onset diabetes, was bedridden by illness at numerous points throughout his life. At the same time, the painting may allude to the slave labor that built the great monuments to the pharaohs. Read this way, the painting serves as a critique of the dehumanizing effect of industry on American workers.

Oil, chalk, and graphite on board - Whitney Museum of American Art

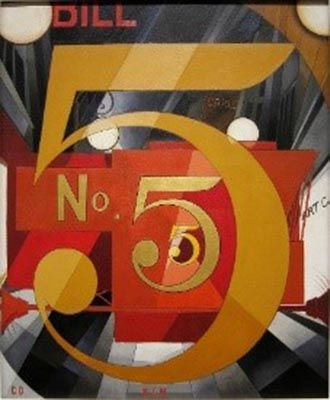

I saw the Figure 5 in Gold

Stricken by lengthy bouts of ill health, Demuth spent many of his later years at home, though he used his art to retain connections with his close circle of friends. These included Marsden Hartley, John Marin, Alfred Stieglitz, Georgia O'Keefe and William Carlos Williams, author of the poem "The Great Figure" on which this, Demuth's most famous work, and perhaps the quintessential Precisionist painting, is based. Between 1924-1929, Demuth created poster portraits that used image and word play to sum up the personality of his "sitters". This work is what we might call a "conceptual portrait" - expressed through typography, gold-leaf and fire-engine red paint - and was created from Williams's poem. His poetry was simple and concise, avoiding metaphor or symbolism:

Among the rain

and lights

I saw the figure 5

in gold

on a red

firetruck

moving

tense

unheeded

to gong clangs

siren howls

and wheels rumbling

through the dark city.

I saw the Figure 5 in Gold depicts what the Met Museum called "the sights and sounds of a fire engine speeding down the street [while the] intersecting lines, repeated '5,' round forms of the numbers, lights, street lamp, and blaring sirens of the red fire engine together infuse the painting with a vibrant, urban energy". The art historian Dr. Lara Kuykendall describes, meanwhile, how "Demuth divided the picture plane into rectangles and triangles, which refract light and change the color of space and shapes", while the "diagonal lines force [our] eyes to race around as [we] try to understand the image". It is, however, the three number "5s" that dominates the image. Kuykendall observes that the "fives get larger as they surge into the foreground (or smaller as they recede into the background), and in the upper right corner you can glimpse the curve of a fourth five as it leaves the surface of the picture and enters your space". She concludes that "with its prismatic chards of space and color and the recurring number five, visualizes the motion and mystery of Williams' experience in a futurist way. It collapses an extended period of time onto one still canvas". With lettering that is reminiscent of sign painting and billboards, Demuth's most iconic image can be read as an early pre-cursor to Pop Art.

Oil on canvas - The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York

Bright Light at Russell's Corners

Although Ault's series of paintings of Russell's Corners in Woodstock NY meticulously depict a collection of farm buildings, they still feel strangely alien. The buildings in the image (as the title indicates) are illuminated by a single, bright light but the scene is mysterious and dark, almost reminiscent of the empty streets of a 1940s film noir. The strikingly lit telephone wires fragment the image into angular planes, although Ault was not so interested in the avant-garde influences of his contemporaries.

Like other Precisionists, Ault was interested in how the old landscape was giving way to one that was altogether more industrialised. But his images of lonely farm buildings reflected Ault's tendency to isolate himself from others and the expansive darkness perhaps expresses the artist's depressed state of mind. Art historian Alexander Nemerov has written how this lonely crossroads held some "mystical power" for Ault. "He fixated on them - painting Russell's Corners five times in the 1940s, in different seasons and times of day - as if they contained some universal truth that would be revealed if he and the viewers of his paintings meditated on them long enough".

Oil on canvas - Smithsonian American Art Museum

Beginnings and Development

It is not clear who first coined the term Precisionism. It may have been Charles Sheeler, one of the movement's foremost painters, or, as seems most likely, Alfred H. Barr, the first director of the Museum of Modern Art in New York City, in 1927. In other sources, art historian Wolfgang Born is credited with the first use of the term when he applied it in 1947, while others claim that it was not until 1960, when the Walker Art Center in Minneapolis mounted "The Precisionist View in American Art" exhibition, that the movement was officially recognized. Whatever the original source of the term, its practitioners attracted the early support of patrons including Charles Daniel (owner of the Daniel Gallery), Stephen Bourgeois (the Bourgeois Gallery), Alfred Stieglitz (the 291 Gallery, Intimate Gallery and An American Place), Gertrude Vanderbilt Whitney (the Whitney Studio Club) and, moving into the 1930s, the Whitney Museum of American Art.

The challenge for historians is that Precisionism was never a formal school or movement, one supported, perhaps, by a published manifesto. It was, rather, a philosophical outlook shared by several American painters and photographers during the early decades of the twentieth century. The group - who have been referred to variously as "Cubist-Realists", "Immaculates", "Sterilists" and "Modern Classicists" - shared an interest in celebrating the dynamism of the modern industrial America and conveyed this aspect of modernity through precise lines and pared back geometric forms. The key Precisionists have been identified (in no order of preference) as Sheeler, George Ault, Ralston Crawford, Francis Criss, Charles Demuth, Preston Dickinson, Elsie Driggs, Louis Lozowick, Gerald Murphy, Georgia O'Keeffe, Niles Spencer, Morton Schamberg, Joseph Stella, Alfred Stieglitz and Paul Strand.

Early Encounters with Modernism

Probably the most influential single figure in introducing European modernism to American audiences was the photographer, publisher and gallery owner Alfred Stieglitz. A pioneer of modern photography himself, Stieglitz, with his friend and colleague Edward Steichen, established the 291 Gallery in New York which operated between 1905 and 1917. Stieglitz's goal was to elevate photography to the same status as painting and sculpture and his gallery became not only an exhibition home for the so-called "Photo-Secession Group", but also the country's first exhibition space for imported works by European avant-garde artists such as Henri Matisse, Henri Rousseau, Pablo Picasso, Auguste Rodin, Paul Cézanne, Marcel Duchamp and Francis Picabia.

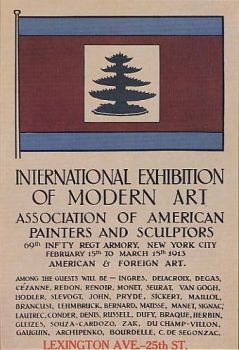

However, it was through the International Exhibition of Modern Art (known as the Armory Show since it was staged in vast US National Guard armouries) of 1913 that announced Fauvism, Cubism and Futurism to the wider populous. The Armory Show would prove a landmark event in American art history and provided the catalyst for American artists who wanted to create their very own artistic language. Stieglitz said the challenge now facing domestic artists was to establish a national art movement that represented "America without that damned French flavour!".

Another significant figure in introducing European modernism to America was Walter Arensberg who became a major collector of modern art after the Armory Show. Walter, and his wife, Louise, became close friends with Duchamp who they set up in a studio apartment on New York's 67th Street. Walter even collaborated with Duchamp on "assisted readymades" such as Comb and With Hidden Noise (both 1916). In the 1920s, the Arensbergs moved from New York to Los Angeles, taking with them works by Duchamp, Picabia, Rousseau, Braque and Matisse and transforming their home there into a veritable West Coast Salon.

The Birth of Precisionism

As early as 1915 Preston Dickinson was producing European-inspired works that focused on industrial subjects such as factories and granaries. Most of his industrial scenes were, however, drawn from his imagination. Charles Sheeler turned to Precisionism in 1917, two years before his move from Philadelphia to New York. Sheeler's favourite subject was barns, reduced to cuboid masses and surface textures, with all references to the natural setting within which the building stood omitted. "In these paintings I sought to reduce natural forms to the borderline of abstraction, retaining only those forms which I believed to be indispensable to the design of the picture", Sheeler said. In 1923 the art critic Forbes Watson placed Sheeler within a tradition of American production: "in the clean-cut fineness, the cool austerity, the complete distrust of superfluities which we find in some pieces of early American furniture, I seem to see the American root of Sheeler's art". Sheeler also enjoyed a long and successful career as a photographer. In 1921 he had collaborated with the Straight photographer Paul Strand on the film Manhatta, based on quotations from Walt Whitman, and celebrating New York as an architectural phenomenon. Sheeler's photographs also provided blueprints for paintings, combining sharp-focus photographic-like detail with tight abstract cohesion.

Charles Demuth - who in his earlier career had excelled as a watercolorist of still-life florals, a book illustrator, a playwright and writer of short prose pieces for avant-garde journals - had emerged out of a "Cezanne-esque" phase of painting to create cityscapes of churches and factories which were more tightly constructed in a Precisionist manner that borrowed from the Futurists and German-American Expressionist Lyonel Feininger. Demuth was fascinated by grain elevators, water towers, and factory chimneys, although he neither wholly accepted nor disapproved of industrialization. He was also interested in advertising hoardings on buildings and along highways. "America doesn't really care" about art he wrote to Stieglitz. "Still, if one is really an artist and at the same time an American, just this not caring, even though it drives one mad, can be artistic material".

The Maturation of Precisionism

During the 1920s many of the Precisionists exhibited at the Charles Daniel Gallery in New York. When it closed in 1932, Edith Halpert's Downtown Gallery became the primary showcase for Precisionism. Outside a dedicated gallery space, the group featured in The Little Review's Machine Age Exposition held at the Steinway Hall, New York in the spring of 1927. This event brought together paintings, architectural drawings and photography. Encouraged by Duchamp, Jane Heap - the celebrated publisher who, with Margaret Anderson, edited the famous modernist literary journal (The Little Review) - organised the show at which Sheeler, Demuth and Louis Lozowick all participated and served on the Artists' Board.

Writing in the catalogue, Lozowick expressed the belief that America was going toward an "order and organization which found their outward sign and symbol in the rigid geometry of the American city: in the verticals of its smokestacks, in the parallels of its car tracks, the squares of its streets, the cubes of its factories, the arc of its bridges, the cylinders of its gas tanks". Lozowick added that "the history of America is a history of gigantic engineering feats and colossal mechanical constructions [...] The skyscrapers of New York, the grain elevators of Minneapolis, the steel mills of Pittsburgh [...] give the American cultural epic its diapason". Lozowick implored American artists, finally, to celebrate this "underlying mathematical pattern".

Concepts and Trends

Architectural Structure

Precisionism started from the position that all ornamental embellishments should be stripped away and the search for the pure architectural structure should be the focus of aesthetic attention. While self-consciously identifying as Americans, the influence of the European avant-garde is clear and the Precisionists were emboldened to pursue abstract forms, fracture compositions and skew perspective, and to represent the world both perceptually and conceptually.

Drawing predominantly on Cubist and Futurist compositional ideas, and often marrying these pictorial techniques with those derived from photography, the Precisionist artists sometimes strove to present multiple views of a subject, and even represent differences in time and place. Precisionist style was linear, hard edged and brittle. The presence of brushstrokes conveying how the paint was applied was absent, seemingly suggesting that the human being is redundant, perhaps even absent. Critic Alexander Adams wrote, "Precisionist art speaks of perfectionism, attempts to impose control over external chaos and hypersensitivity towards disruption. It is a pathological response akin to phobia of germs or insecurity in the face of change. Precisionism is the art of those averse to imprecision; it speaks of fear of decay and worry about ambiguity and doubt".

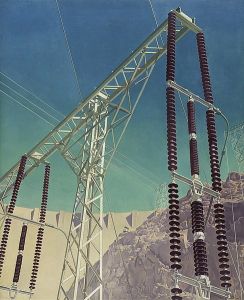

Mechanization

Taking mechanization as subject matter was a reflection of America's investment in progress, its faith in science and engineering, and its positive belief in the virtues of industry. But Precisionist paintings gave rise in certain circles to an ambivalent attitude toward mechanization. Many paintings endow factory and industrial buildings with a kind of monumentality reserved previously for the depiction of churches. Others, however, hint at the dehumanising effect of technology and, with a lack of human presence in the works, the absence of a soul at the heart of modernity. Sheeler often applied his attention to detail to transform mundane objects into transcendent subjects worthy of worship. But The New York Daily Worker commented with a tone of derision that "Sheeler approaches the industrial landscape [...] with the same sort of piety Fra Angelico used toward angels [...] In revealing the beauty of factory architecture, Sheeler has become the Raphael of the Fords".

Photography

The interests of modern photography and Precisionist painting often overlapped in the 1920s. Paul Strand (a one-time junior mentee of Stieglitz) had taken his own inspiration from the paintings of Cezanne, Braque and Picasso and became fixated on the idea that the photographic image could also be broken up compositionally. His initiated the idea of Straight Photography which used large format cameras to create high contrasts (rather than shading), flat, or two-dimensional images, semi-abstractions, and forms of geometric repetition. Stieglitz had been so impressed with Strand's artistic maturation that he himself adopted Strand's Straight Photography aesthetic. In 1917 Stieglitz gave Strand a major exhibition at his 291 Gallery and then allotted two issues of his photography magazine Camera Work entirely to Strand's work.

Through Stieglitz's promotion, the idea of Straight Photography impacted upon the way that Precisionists focussed in on the world, especially in the geometric realism of Sheeler, Demuth and Stella. Sheeler was himself an accomplished commercial photographer and often based his paintings on his photographs. He also employed photographic techniques such as flattened and bowed perspective in some of his painted works. In 1921, Strand and Sheeler collaborated on a short, silent film called Manhatta (AKA: New York the Magnificent). The film, which captured the movement of everyday street life under the architectural shadows of the looming New York skyline, reflected many of Precisionism's aesthetic preoccupations and is widely considered to be the first American avant-garde film.

Later Developments - After Precisionism

By the late 1930s, the USA was providing refuge for artists and architects fleeing fascist Europe. Many of them had been schooled in the Bauhaus tradition which sought unity between art and technology. Bauhaus and Constructivist influences merged with the Precisionist fascination for geometric and architectural forms, which became even more focussed on shape, pattern, and texture. By the 1940s, however, Precisionism's major champions had either passed away, fallen out of fashion, or moved on artistically. Charles Demuth died aged 51 in 1935, having finished a series of seven paintings depicting factory buildings in Lancaster, Pennsylvania. Sheeler stayed true to his Precisionist principles, but focussed increasingly on photography. Precisionism's influence continued to be directly felt, in a more bleak and unsettling manner, in the American Scene Paintings of Charles Burchfield, George Ault and Edward Hopper, the latter becoming the accepted master of small town alienation.

History indicates that Precisionism was a bridge between realism and a more modern American vision, with Abstract Expressionism building upon Precisionism's reductionism but by rooting itself more in the subconscious explorations of Surrealism. As collector Deedee Wigmore observed, "Precisionism was about the search for architectural structure underlying reality, which eventually led American artists out of realism into pure geometric abstraction". Precisionism's impact on advertising imagery and stage and set design, meanwhile, continued throughout the twentieth century, inspiring countless cinematographic visions of bucolic America as well.

Perhaps its most direct influence was felt, however, by Pop artists such as Jasper Johns and Robert Indiana, and especially in their "numbers paintings". The art historian Eli Anapur writes for instance that one painting - Demuth's I Saw the Figure Five in Gold - "holds the foremost place in this equation of significance" for twentieth century American art and argued "its popular subject and angled forms anticipate both Pop and Abstract art". She writes that both movements "slowly emerged from the increased stylization of forms and reduction of details", but it was in fact "Demuth's poster-portraits - specific in their depictions of letters and everyday commercial objects instead of figures [that] are some of the earliest examples of such imagery in American Art" and these directly "inspired similar Pop Art renderings of consumer objects".

Useful Resources on Precisionism

- Cult of the Machine: Precisionism and American ArtBy Emma Acker

- America's Cool Modernism: O'Keeffe to HooperBy Katherine Bourgignon

- Precisionism in America 1915-1941: Reordering RealityBy Diana Murphy

- Stuart Davis: In Full SwingBy Barbara Haskell

- Charles Sheeler: Modernism, Precisionism and the Borders of AbstractionBy Mark Rawlinson

- Chimneys and Towers: Charles Demuth's Late PaintingsBy Betsy Fahlman

- Georgia O'Keefe: New York YearsBy Doris Bry and Nicholas Callaway

- Joseph StellaBy Barbara Haskell

- Joseph Stella's SymbolismBy Irma B. Jaffe

- To Make a World: George Ault and 1940s AmericaBy Alexander Nemerov

- Elsie Driggs: The Quick and the ClassicalBy Constance Kimmerle

- Morton Livingston Schamberg: a MonographBy Ben Wolf

Ask The Art Story AI

Ask The Art Story AI