Summary of Rococo

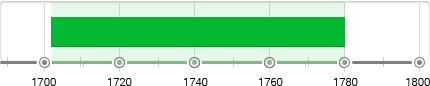

Centuries before the term "bling" was invented to denote ostentatious shows of luxury, Rococo infused the world of art and interior design with an aristocratic idealism that favored elaborate ornamentation and intricate detailing. The paintings that became signature to the era were created in celebration of Rococo's grandiose ideals and lust for the aristocratic lifestyle and pastimes. The movement, which developed in France in the early 1700s, evolved into a new, over-the-top marriage of the decorative and fine arts, which became a visual lexicon that infiltrated 18th century continental Europe.

Key Ideas & Accomplishments

- Genre paintings were popular ways to represent the Rococo period's bold and joyous lust for life. This included fete galante, or works denoting outdoor pastimes, erotic paintings alive with a sense of whimsical hedonism, Arcadian landscapes, and the "celebrity" portrait, which positioned ordinary people in the roles of notable historical or allegorical characters.

- Rococo art and architecture carried a strong sense of theatricality and drama, influenced by stage design. Theater's influence could be seen in the innovative ways painting and decorative objects were woven into various environments, creating fully immersive atmospheres.

- Detail-work flourished in the Rococo period. Stucco reliefs as frames, asymmetrical patterns involving motifs and scrollwork, sculptural arabesque details, gilding, pastels, and tromp l'oeil are the most noted methods that were used to achieve a seamless integration of art and architecture.

- The term "rococo" was first used by Jean Mondon in his Premier Livre de forme rocquaille et cartel (First book of Rococo Form and Setting) (1736), with illustrations that depicted the style used in architecture and interior design. The term was derived from the French rocaille, meaning "shell work, pebble-work," used to describe High Renaissance fountains or garden grottos that used seashells and pebbles, embedded in stucco, to create an elaborate decorative effect.

Artworks and Artists of Rococo

The Embarkation for Cythera

This painting depicts a number of amorous couples in elegant aristocratic dress within an idealized pastoral setting on Cythera, the mythical island where Venus, the goddess of love, birthed forth from the sea. The gestures and body language are evocative, as the man standing below center, his arm around the waist of the woman beside him, seems to earnestly entreat her, while she turns back to gaze wistfully at the other couples. A nude statue of the goddess rises from a pedestal that is garlanded with flowers on the right, as if presiding over the festivities. On the left, she is doubly depicted in a golden statue that places her in the prow of the boat. Nude putti appear throughout the scene, soaring into the sky on the left, or appearing between the couples and pushing them along, and nature is a languid but fecund presence. Overall, the painting celebrates the journey of love. As contemporary critic Jeb Perl wrote, "Watteau's paired lovers, locked in their agonizing, delicious indecision, are emblems of the ever-approaching and ever-receding possibility of love."

As art critic Holly Brubach wrote, "Watteau's images are perfectly suspended between the moment just before and the moment after... the people he portrays are busy enacting not one but several possible scenarios." His figures are not so much recognizable individuals, as aristocratic types, with smooth powdered faces, that together create a kind of choreography of color and pleasure.

With this work, Watteau's reception piece for the Academy, he pioneered the fête galante, or courtship painting, and launched the Rococo movement. As Jonathan Jones wrote, "In the misty, melting landscapes of paintings ... he unequivocally associates landscape and desire: if Watteau's art looks back to the courtly lovers of the middle ages it begins the modern history of sensuality in French art."

Oil on canvas - Musée du Louvre, Paris

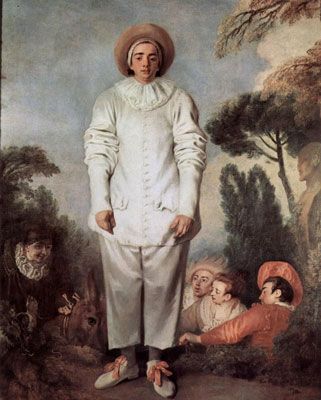

Pierrot

This painting (formerly known as Gilles) depicts Pierrot, a traditional character in Italian commedia dell'arte. He is elevated on center stage in what appears to be a garden and he faces the viewer with a downcast expression as his white satin costume dominates, its ballooning midsection lit up. He seems almost like a two-dimensional cut-out figure. Other stock characters surround him but Pierrot remains separate as if he has stepped out of their scene. The negative space in the upper left further emphasizes Pierrot's isolation. As Jonathan Jones wrote, "Watteau makes the fiction of the picture manifest," as the character, "in his discomfort and alienation, rebels not only against his stock character role in the comedy, but his role in this painting. His stepping out of the play is also a stepping out of the fiction painted by Watteau."

Watteau pioneered the artistic representation of theatrical worlds, a distinctive Rococo genre, and he also recast the character of Pierrot from a kind of bumbling, lovelorn fool into a figure of alienated longing. As Jones wrote, "representation of theatrical, socially marginal worlds, following Watteau, is central to French modern art, from the impressionists' cafe singers to Toulouse-Lautrec's dancers and prostitutes and Picasso's Harlequins." As the figure of Pierrot became a figure of the artist's alter ego, this painting influenced a number of later art movements and artists, including the Decadents, the Symbolists, and artists like André Derain, as seen in his Harlequin and Pierrot (c. 1924). The influence also extended to pop culture as shown in David Bowie's early performance in Lindsay Kemp's Pierrot in Turquoise (1967) where Bowie said, "I'm Pierrot. I'm Everyman. What I'm doing is theatre, and only theatre. What you see on stage isn't sinister. It's pure clown. I'm using myself as a canvas and trying to paint the truth of our time."

Oil on canvas - Musée du Louvre, Paris

The Entrance to the Grand Canal

This noted landscape depicts the entrance to the Grand Canal in Venice, with a number of gondoliers and their passengers maneuvering horizontally across the canvas. Their asymmetrical placement creates movement as three gondolas extend upward in the center and draw the viewer's eye into the distance, further emphasized by the perspective of the buildings on the right and the church on the left. The subtle use of local colors give the piece a golden feel and a sense of the idyllic life of the times, which was informed by the Venetian school's love of Arcadian landscapes that heavily informed the Rococo aesthetic.

Canaletto was a pioneer in painting from nature and conveying the atmospheric effects of a particular moment, which has led some scholars to see his work as anticipating Impressionism. As Jonathan Jones wrote, "the delicate feel for light playing on architecture...makes Canaletto so beguiling." At the same, his innovative use of topography, rendering a locale with scientific accuracy, influenced subsequent artists, as art historian John Russell noted, "he took hold of his native city as if no detail of its teeming life was too small or too trivial to deserve his attention."

Venice was a noted stop for British aristocrats on the Grand Tour, and most of Canaletto's work was sold to this audience. The British art dealer Owen Swiny encouraged him to paint small, even postcard-sized, topographical views to sell to tourists, and the banker and art collector, Joseph Smith, became a noted patron, selling a large number of his works to King George III. In 1746 Canaletto moved to London where he painted scenes of London, such as his Westminster Bridge (1746). Ever since his work has retained its popularity and influence: it was featured in the David Bickerstaff film Canaletto and the Art of Venice (2017), and this painting was used in the video game Merchant Prince II (2001).

Oil on canvas - Museum of Fine Arts, Houston, Texas

Soap Bubbles

This painting depicts two children at play. An older boy, leaning forward, blows through a reed, expanding a luminous soap bubble. A younger child in shadow, wearing a cap with a plume, peers over the ledge, his gaze also focused on the shimmering bubble. The color palette, muted with various shades of rich brown and black, emphasizes the contrasting light and ruddy glow of the boy's hands and face, so that the viewer too becomes aware of the hushed absorption in childhood play. The paint applied with a thick impasto conveys the tactile textures of stone, fabric, and skin. The work creates a feeling of childhood innocence focused on an ephemeral joy, while also being allusive, as the artist's contemporaries would have registered the soap bubble as a symbol of life's transience.

Influenced by Dutch Golden Age genre painters, Chardin's realistic genre scenes were his unique contribution to the Rococo period. Unlike most artists who focused on the aristocracy and its entertainments, he depicted domestic scenes, children at play, and still lifes, all reflecting the Rococo's homage to leisurely pastimes. As Jones also wrote, Chardin painted "the world of middle-class pleasures" and the "French aesthetic of the everyday ...appears for the first time in Chardin's paintings and made him a cult figure for modern French artists and writers." His work influenced Gustave Courbet, Paul Cézanne, Édouard Manet, and Vincent Van Gogh, among others.

Oil on canvas - The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York

La Toilette de Vénus (The Toilet of Venus)

This portrait depicts a nude Madame de Pompadour in the guise of Venus, the classical goddess of love, attended by three cherubs and two white doves. She sits on a chaise lounge, its back framed with gold rocaille topped with a statue of a reclining cherub.

Blue drapes, luminescent with light and shadow, open to a partial view of a beautiful garden, frame the scene with an atmosphere of leisure. The figurative treatment is idealized, almost air-brushed, while the setting is ornately detailed and decorative, creating an overall effect that embodies the concept of luxury itself.

Boucher transformed the Rococo period with his sensual depictions of the era's notable citizens, social celebrities, and past times, creating his own distinct, pictorial brand. A veritable "who's who of the time", Madame de Pompadour commissioned Boucher to paint this work for her private dressing room in the Chateau de Bellevue. The painting was a tribute to her, as she had played the title role of Venus in La Toilette de Venus (1750) at Versailles.

As art historian Melissa Lee Hyde wrote, Boucher's portraits often pointed "to an interesting conflation of theatrical/performed identities and lived identities," showing "a passion for what we might call the art of appearance and an understanding of that art as a vehicle for fashioning and representing identity."

Within a few decades, Neoclassicism repudiated Boucher's work for the same qualities that made it so popular among the aristocratic class. His work has only recently begun to be re-evaluated by art historians such as Melissa Lee Hyde and Jed Perl, and contemporary artists John Currin and Lisa Yuskavage have cited Boucher as a direct influence.

Oil on canvas - The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York

Portrait of Madame de Pompadour

This full-length portrait of Madame de Pompadour emphasizes stylish elegance, as she reclines in an exuberant green silk dress with a pattern of pink roses across her bodice and neckline. The room's interior, framed by gold brocade draperies with an elaborate gold cartel clock displayed over the fireplace, is equally resplendent. The details are also symbolic, as the bookcase full of books, the books scattered on the floor, and the clock shaped as a lyre and decorated with laurel, symbolize the love of literature, music, and poetry. She conveys both an air of confidence and pleasurable relaxation, her pink high heels peeking from below her skirt, two beautiful roses lying at her feet. Yet the work also depicts her intellectual influence, an open book in her left hand, a writing quill and an envelope on the table to the right. Turning her gaze to the left was, at the time, a pose that represented being engaged in philosophical thought. As a result, the work is a kind of social iconography, each element, carefully chosen and stylistically unified to create an exemplary image.

Described by art critic Suzy Menkes, as "one of the earliest and most successful self-image makers," Madame de Pompadour commissioned this portrait, along with others by Boucher, and requested to see them, while they were in progress, so she could direct how she wished to appear. As Menkes noted, Boucher's "flattering and decorative paintings" were an early artistic example of "the celebrity tabloid treatment." In 1756 Pompadour was appointed lady-in-waiting at the court, and art historian Elise Goodman suggests that the moment depicted here, noted by the 8:20 on the clock, was meant to commemorate, "her elevation, when, at the height of aristocratic self-confidence...she withdrew to her library-boudoir to luxuriate in her new position and enjoy the activities she loved."

Boucher's images of Madame Pompadour so characterized the Rococo movement that the writers Jules and Edmond de Goncourt were to write, "In a letter on the taste of the French, which is part of a collection of manuscript ephemera dating from 1751...I found carriages a la Pompadour, cloth in the couleur Pompadour, ragouts a la Pompadour... there is not a single scrap pertaining to the toilette of a woman that is not a la Pompadour."

Oil on canvas - Alte Pinakothek, Munich, Germany

The Swing

This iconic work depicts a fanciful woman flying on a swing in a verdant garden, her dress blooming like an extravagant pink flower, as a young dandy falls back into the bushes on the left, his face blushing with excitement to look up her skirt. In the shadows at the right an older man is pulling on the swing's ropes to propel the young woman forward. Beneath her are two embracing cherubs and at the left, another cupid stands on a pedestal holding his hand up to his lips in admonition. The image was scandalous for its time because of its densely layered sexual allusions.

Fragonard's expressive brushstrokes create a swirling flow between figure and foliage, so that nature itself seems to be caught up in the excitement of the moment. At the same time, the artist used light and shadow to direct the viewer's eye toward discovering the work in stages. The viewer notices first the woman on the swing, then the young man, and, finally, the older man in shadow at the right. The effect is one of a kind of stage lighting, creating drama and narrative.

Fragonard's work was rediscovered by the writers Edmund and Jules de Goncourt in L'Art du XVIIIe siècle (Eighteenth-Century Art) (1865), and his work subsequently influenced the Impressionists, particularly Pierre-Auguste Renoir and Berthe Morisot, who was also his granddaughter. The Swing has become an artistic and cultural icon. It was revisited by contemporary artists Yinka Shonibare and Kent Monkman in their own work. Balloon artist Larry Moss referred to it in his 3D installation of The Swing for his Masterworks series at the Phelps Art Center in 2013.

Oil on canvas - Wallace Collection, London

Allegory of the Planets and Continents

This gorgeously festive depiction of the sun's course across the sky is presented in an operatic splendor of swirling arabesques, color, and light. At left of center, the Greek sun god Apollo stands with the radiant orb behind him, calling up the sun horses on his right. On the cornice, groups of allegorical figures with representative animals denote Europe, Asia, America, and Africa, while the gods, symbolizing the planets, swirl around the sun god. Mars, the god of war, is reclining with a nude Venus, on a dark cloud beneath Apollo, while Mercury with his caduceus in hand flies down from the upper left.

This painting was made for a dazzling staircase ceiling he created at the Würzburg Residenz in Germany for the prince-bishop Carl Phillip von Grieffenklau. Painted on an enormous vault, Tiepolo's trompe l'oeil treatment created a dramatic impression in contrast to the white marble Neoclassical staircase designed by Balthasar Neumann. Tiepolo's painting of the Europe section includes a portrait of the architect, as well as of von Grieffenklau. Additionally, the artist portrayed his son Giandomenico and the artist Antonio Bossi, both of whom worked with him on the project, and a self-portrait.

This fresco remains the largest in the world, composed so that the painting's individual sections could be viewed from a particular stopping place, as if the perspective adjusted to the position of the viewer. Tiepolo's innovation was his arrangement of pastels in a complementary scheme, so that the tension in the color would emphasize the narrative movement and the dramatic poses of the figures to create a lively effect. The result was called sprezzatura, or a "studied carelessness." As art historian Keith Christiansen wrote, Tiepolo "celebrates the imagination by transposing the world of ancient history and myth, the scriptures, and sacred legends into a grandiose, even theatrical language." It was this quality of Tiepolo's imagination that influenced Francisco Goya throughout his career, both in his early tapestry designs and later in his etchings as he drew upon Tiepolo's mysterious and sometimes bizarre prints in the Capricci (c. 1740-1742) and the Scherzi di fantasia (c. 1743-1757).

Oil on canvas

The Blue Boy

This full-length portrait depicts a boy, wearing blue satin knee breeches and a lace-collared doublet as he gazes, unsmiling, at the viewer. Holding a plumed hat in his right hand, his other hand cocked on his hip, he conveys both self-confidence and a touch of swagger. Composed in layers of slashed and fine brushstrokes with delicate tints of slate, turquoise, cobalt, indigo, and lapis lazuli, the blue becomes resplendent, almost electric against the stormy and rocky landscape.

Originally, the painting was thought to portray Jonathan Buttall, the son of a wealthy merchant, but contemporary scholarship has identified the model to most likely be the artist's assistant and nephew Gainsborough Dupont. As art critic Kimberly Chrisman-Campbell wrote, the work "is a kind of English Civil War cosplay popular for masquerade balls in the 18th century," depicting the boy in the outfit of a cavalier, worn by aristocratic Royalists of the 1630s. His posture and facial expression play the part as well, for cavaliers were defined not only by their stylish clothing but their nonchalant and swashbuckling attitude. Thus, the work, Gainsborough's most popular, is a tour de force, combining masterful portraiture with a costume study and his artistic reply to the works of Anthony van Dyck, famous for his portraiture of King Charles I's court and the cavaliers who supported him. Yet, by primarily using blue, traditionally thought to be more suited for background elements, Gainsborough also challenged traditional aesthetic assumptions.

The work carries Rococo's traditional visual appeal and play with costumed figures, but Gainsborough also added innovative elements of realism, as seen in the buttons tightly lacing the doublet together, and prefigured Romanticism by portraying a solitary figure outlined against a turbulent sky. Gainsborough came to exemplify British Rococo with society portraits of his wealthy clients.

The painting was immediately successful at its 1770 debut at the Royal Academy of Art in London and became so identified with British cultural identity that, when in 1921 the Duke of Westminster sold it to the American tycoon Henry Huntington, it caused a scandal. Friedrich Wilhelm Murnau's silent film Knabe in Blau (The Boy in Blue) (1919) was inspired by the painting, as was Cole Porter's song Blue Boy Blues (1922). Pop artist Robert Rauschenberg and contemporary artist Kehinde Wiley were inspired by the work, and artist Alex Israel referenced it in his Self Portrait (Dodgers) (2014‒2015). Shown at the Huntington Museum, paired with Thomas Lawrence's portrait of a girl in pink, Pinkie (1794), the work has taken on further cultural relevance, as both paintings have been used in the TV pilot for Eerie, Indiana (1991) and as set decorations on episodes of Leave It to Beaver (1957-1963).

Oil on canvas - Huntington Library, San Marino, California

Self-Portrait with Straw Hat

This self-portrait emphasizes both aristocratic but casual elegance and artistic prowess. Dressed in shimmering silk, her white cuffs drawing attention to her extended right hand, her white collar emphasizing the daring cut of her neckline, she holds a palette and brushes in her left hand. The wide brimmed straw hat, encircled with vibrant flowers and sporting, becomes a focal point of the work's emphasis on the play of light, as the upper part of her face is softly shadowed, bringing forth her confident direct gaze, while sunlight illuminates the right side of her face and her upper torso. Two long crystal earrings play counterpoint, echoing light and shadow. The background is only sky, its robin's egg blue framing her face, and the overall effect is as art historian Simon Schama wrote, "a fetching but carefully calculated nonchalance."

This work was influenced by Peter Paul Rubens' Le Chapeau de Paille (The Straw Hat) (1622-1625). After seeing it in Antwerp, Le Brun wrote, "it delighted and inspired me to such a degree that I made a portrait of myself at Brussels, striving to obtain the same effects."

Women artists were confined to portraiture for the most part. A number of renowned female Rococo artists included Rosalba Carriera, Adélaïde Labille-Guiard, and Angelica Kauffman. The most well known was Vigée Le Brun, who, at the age of twenty-three, became the official painter for Queen Marie Antoinette. Le Brun's innovations were in portraiture, as Schama wrote, "[n]o one, it became quickly apparent...could compete with this young woman as an artist of artlessness, " and her "great breakthrough is to remake women, immemorially the prisoner of male ogling, into the unmistakable mistress of their own presence."

Oil on canvas - The National Gallery, London

Beginnings of Rococo

In painting Rococo was primarily influenced by the Venetian School's use of color, erotic subjects, and Arcadian landscapes, while the School of Fontainebleau was foundational to Rococo interior design.

The Venetian School

The noted painters Giorgione and Titian, among others, influenced the Rococo period's emphasis on swirling color and erotic subject matter. Pastoral Concert (c. 1509), first attributed to Giorgione, though now credited by most scholars as one of Titian's early works, was classified as a Fête champêtre, or outdoor party, by the Louvre when it first became part of the museum's collection. The Renaissance work depicting two nude women and two aristocratic men playing music in an idealized pastoral landscape would heavily influence the development of Rococo's Fête galante, or courtship paintings. The term referred to historical paintings of pleasurable past times and became popularized in the works of Jean-Antoine Watteau.

School of Fontainebleau 1528-1630

In 1530 King Francis I, a noted art patron, invited the Italian artist Rosso Florentino to the French court, where, pioneering the courtly style of French Mannerism, Rosso founded the School of Fontainebleau. The school became known for its unique interior design style in which all the elements created a highly choreographed unity. Rosso pioneered the use of large stucco reliefs as frames, adorned with decorative and gilded motifs that would heavily influence Rococo's emphasis on elaborated settings.

Gilding was a key contribution of Fontainebleau, providing exquisite splendor to objects as seen in Benevento Cellini's famous Salt Cellar (1543), which Francis I commissioned in gold. Even simple elements of Rococo interiors became highly accentuated as seen in the popularity of cartel clocks, embedding regular clocks into intricate settings that resembled pieces of sculpture, and which seamlessly complemented the overall look and feel of their surrounding interiors.

The Era of Rococo Design

Rococo debuted in interior design when engraver Pierre Le Pautre worked with architect Jules Hardouin-Mansart on the Château de Marly (1679-1684), and later at Versailles in 1701 when he redesigned Louis XIV's private apartments. Le Pautre pioneered the use of arabesques, employing an s-shaped or c-shaped line, placed on white walls and ceilings. He also used inset panels with gilded woodwork, creating a whimsical, lighter style. Le Pautre was primarily known as an ornemaniste, or designer of ornament, which reflects the popular role at the time of artisans and craftsmen in developing the highly decorative style.

During the reign of Louis XIV, France had become the dominant European power, and the combination of great wealth and peaceful stability led the French to turn their attention toward personal affairs and the enjoyment of worldly pleasures. When the King died in 1715, his heir Louis XV was only five years old, so the Regency, led by the Duc d' Orléans, ruled France until the Dauphin came of age. The Duke was known for his hedonistic lifestyle, and Rococo's aesthetics seemed the perfect expression of the era's sensibility. Taking the throne in 1723, Louis XV also became a noted proponent and patron of Rococo architecture and design. Since France was the artistic center of Europe, the artistic courts of other European countries soon followed suit in their enthusiasm for similar embellishments.

Jean-Antoine Watteau

Jean-Antoine Watteau spearheaded the Rococo period in painting. Born in Valenciennes, a small provincial village in Belgium that had recently been acceded to the French, his precocity in art and drawing led to his early apprenticeship with a local painter. Subsequently he went to Paris where he made a living producing copies of works by Titian and Paolo Veronese. He joined the studio of Claude Audran, who was a renowned decorator, where he met and became an artistic colleague of Claude Gillot, known for his decoration of commedia dell'arte, or comic theater productions. As a result, Watteau's work often expressed a theatrical approach, showing figures in costume amongst backdrop scenery, lit up with artificial light.

In 1712 Watteau entered the Prix de Rome competition of the Académie Royale de Peinture et de Sculpture, and the Academy admitted him as a full member. His "reception piece" for the Academy, Embarkation for Cythera (1717), effectively launched the Rococo movement. The Academy coined the term Fête galante, or courtship party, to refer to the work, thus establishing the category that was to be a dominant element of Rococo painting. Fête galante paintings depicted the fête champêtre, or garden party, popular among the aristocratic class, where, dressed as if for a ball or wearing costumes, they would wine, dine, and engage in amorous pursuits within Arcadian gardens and parks. The artistic subject not only appealed to private patrons, but its mythologized landscapes and settings met the standards of the Academy which ranked historical painting, including mythological subjects, as the highest category.

Claude Audren was the official Keeper of the Luxembourg Palace and, while working with him, Watteau copied Peter Paul Ruben's series of twenty-four paintings of the Life of Marie de' Medici (1622-25), which was displayed at the palace. Ruben's series, combining allegorical figures and mythological subjects with depictions of the Queen and the aristocratic court, continued to inform Watteau's work. Rubens had pioneered the technique of trois crayons, meaning three chalks, a technique using red, black, and white, to create coloristic effects. Watteau mastered the technique to such a degree that his name became associated with it, and it was widely adopted by later Rococo artists, including François Boucher.

François Boucher

Influenced by Rubens and Watteau, François Boucher became the most renowned artist of the mature Rococo period, beginning in 1730 and lasting until the 1760s. Noted for his painting that combined aristocratic elegance with erotic treatments of the nude, as seen in his The Toilet of Venus (1751), he was equally influential in decorative arts, theatrical settings, and tapestry design. He was appointed First Painter to the King in 1765, but is most known for his long time association with Madame de Pompadour, the official first mistress of King Louis XV and a noted patron of the arts. As a result of his mastery of Rococo art and design and his royal patronage, Boucher became "one of those men who represent the taste of a century, who express, personify and embody it," as the noted authors Edmond and Jules de Goncourt wrote.

Madame de Pompadour

Madame de Pompadour, born Jeanne-Antoinette Poisson, has been called the "godmother of the Rococo," due to her centrality in promoting the style and establishing Paris as the artistic capital of Europe. She influenced further applications of Rococo due to her patronage of artists such as Jean-Marc Nattier, the sculptor Jean Baptiste Pigalle, the wallpaper designer Jean-Baptiste Réveillon, and the gemstone engraver Jacques Guay. The King's official first mistress from 1745-1751, she remained his confidant and trusted advisor until her death at the age of 42 due to tuberculosis. Her role and status became the de facto definition of royal patronage.

Rococo: Concepts, Styles, and Trends

French Rococo

France was the center of the development of Rococo. In design, the salon, a room for entertaining but also impressing guests, was a major innovation. The most famous example was Charles-Joseph Natoire and Germain Boffrand's La Salon de la Princesse (1735-1740) in the residence of the Prince and Princess de Soubise. The cylindrical interior's white walls, gilded wood, and many mirrors created a light and airy effect. Arabesque decorations, often alluding to Roman motifs, cupids, and garlands, were presented in gold stucco and plate relief. Asymmetrical curves, sometimes derived from organic forms, such as seashells or acanthus fronds, were elaborate and exaggerated. The minimal emphasis on architecture and maximum emphasis on décor would become cornerstone to the Rococo movement.

Painting was an essential part of the Rococo movement in France, and the noted painters who led the style, Antoine Watteau followed by François Boucher, influenced all elements of design from interiors to tapestries to fashion. Other noted artists included Jean-Baptiste van Loo, Jean-Marc Nattier, and François Lemoyne. Lemoyne was noted for his historical allegorical paintings as seen in his Apotheosis of Hercules (1733-1736) painted on the Salon of Hercules' ceiling at Versailles. A noted feature of French Rococo painting was the manner in which a number of noted artist families, such as the van Loos and the Coypels, maintained a consistent style and subject matter in their workshops.

Italian Rococo

Painting took the lead in Italian Rococo, exemplified by the works of the Venetian artist Tiepolo. Combining the Venetian School's emphasis on color with quadratura, or ceiling paintings, Tiepolo's masterworks were frescos and large altarpieces. Famed throughout Europe, he received many royal commissions, such as his series of ceiling paintings in the Wurzburg Residenz in Germany, and his Apotheosis of the Spanish Monarchy (1762-1766) in the Royal Palace in Madrid.

Italian Rococo was also noted for its great landscape artists known as "view-painters," particularly Giovanni Antonio Canal, known simply as Canaletto. He pioneered the use of two-point linear perspective while creating popular scenes of the canals and pageantry of Venice. His works, such as his Venice: Santa Maria della Salute (c. 1740), were in great demand with English aristocrats. In the 1700s it became customary for young English aristocrats to go on a "Grand Tour," visiting the noted sites of Europe in order to learn the classical roots of Western culture. The trips launched a kind of aristocratic tourism, and Venice was a noted stop, famed for its hedonistic carnival atmosphere and picturesque views. These young aristocrats were also often art collectors and patrons, and most of Canaletto's works were sold to an English audience, and in 1746 he moved to England to be closer to his art market and lived there for almost a decade.

Rosalba Carriera's pastel portraits, both miniature and full-size, as well as her allegorical works were in demand throughout Europe, as she was invited to the royal courts of France, Austrian, and Poland. She pioneered the use of pastels, previously only employed for preparatory drawings, as a medium for painting, and, by binding the chalk into sticks, developed a wider range of strokes and prepared colors. Her Portrait of Louis XV as Dauphin (1720-1721) established the new style of Rococo portraiture, emphasizing visual appeal and decorative effect.

In architecture, Italy continued to emphasize the Baroque with its strong connection to the Catholic church until the 1720s when the architect Filippo Juvarra built several Northern Italian Palaces in the Rococo style. His masterwork was the Stupinigi Palace (1729-1731), built as the hunting lodge for the King of Sardinia in Turin. At the same time, Rococo interiors became popular in Genoa, Sardinia, Sicily, and Venice where the style took on regional variations particularly in furniture design. Italian Rococo interiors were particularly known for their Venetian glass chandeliers and mirrors and their rich use of silk and velvet upholstery.

German Rococo

Germany's enthusiasm for Rococo expressed itself exuberantly and primarily in architectural masterpieces and interior design, as well as the applied arts. A noted element of German Rococo was the use of vibrant pastel colors like lilac, lemon, pink, and blue as seen in François de Cuvilliés' design of the Amalienburg (1734-1739), a hunting lodge for the Holy Roman Emperor Charles VII in Munich. His Hall of Mirrors in the Amalienburg has been described by art historian Hugh Honour as exemplifying "easy elegance and gossamer delicacy."

German design motifs while employing asymmetry and s- and c- curved shapes, often drew upon floral or organic motifs, and employed more detail. German architects also innovatively explored various possibilities for room designs, cutting away walls or making curved walls, and made the siting of new buildings an important element of the effect, as seen in Jacob Prandtauer's Melk Abbey (1702-1736)

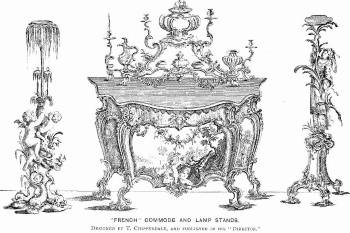

English Rococo

England's employment of Rococo, which was called "French style," was more restrained, as the excesses of the style were met with a somber Protestantism. As a result, rocaille introduced by the émigré engraver Hubert-François Gravelot and the silversmith Paul de Lamerie, was only employed as details and occasional motifs. Around 1740 the Rococo style began to be employed in British furniture, most notably in the designs of Thomas Chippendale. His catalogue Gentleman's and Cabinet-makers' directory (1754), illustrating Rococo designs, became a popular industry standard.

Rococo had more of an impact upon British artists such as William Hogarth, Thomas Gainsborough, and the Swiss Angelica Kauffman. In his The Analysis of Beauty (1753) Hogarth advocated for the use of a serpentine line, seeing it as both more organic and aesthetically ideal. Gainsborough first studied with Gravelot, a former student of Boucher, whose feathery brushwork and color palette influenced Gainsborough's portraiture toward fluidity of light and color. Though Swiss-born, Angelica Kauffman spent most of her life in Rome and London. From 1766 to 1781 she lived in London where influential Sir Joshua Reynolds particularly admired her portraiture. One of only two women elected to the Royal Academy of Arts in London, she played a significant role in both advancing the Rococo style and, subsequently, Neoclassicism.

Later Developments - After Rococo

In 1750 Madame de Pompadour sent her nephew Abel-François Poisson de Vandières to study developments in Italian art and archeology. Returning with an enthusiasm for classical art, Vandières was appointed director of the King's Buildings where he began to advocate for a Neoclassical approach. He also became a noted art critic, condemning Boucher's petit style, or "little style." Noted thinkers of the day, including the philosopher Voltaire, the art critic Diderot also critiqued Rococo as superficial and decadent. These trends, along with a rising revolutionary fervor in France caused Rococo to fall out of favor by 1780.

The new movement Neoclassicism, led by the artist Jacques-Louis David, emphasized heroism and moral virtue. David's art students even sang the derisive chant, "Vanloo, Pompadour, Rococo," singling out the style, one of its leading artists, and it most noted patron. As a result, by 1836 it was used to mean "old-fashioned," and by 1841 was used to denote works seen as "tastelessly florid or ornate." The negative connotations continued into the 20th century, as seen in the 1902 Century Dictionary description "Hence rococo is used... to note anything feebly pretentious and tasteless in art or literature."

Rococo design and painting would veer toward divergent paths, as Rococo design, despite the new trends in the capital, continued to be popular throughout the French provinces. In the 1820s under the restored monarchy of King Louis Philippe, a revival called the "Second Rococo" style became popular and spread to Britain and Bavaria. In Britain the revival became known as Victorian Rococo and lasted until around 1870, while also influencing the American Rococo Revival in the United States, led by John Henry Belter. The style, widely employed for upscale hotels, was dubbed "Le gout Ritz" into the 20th century. However, in painting Rococo fell out of favor, with the exception of the genre paintings of Chardin, highly praised by Diderot, which continued to be influential and would later make a noted impact on Paul Cézanne, Édouard Manet, and Vincent van Gogh.

Edmund and Jules de Goncourt rediscovered the major Rococo painter Jean-Honoré Fragonard in L'Art du XVIIIe siècle (Eighteenth-Century Art) (1865). He subsequently influenced the Impressionists, especially Pierre-Auguste Renoir and Berthe Morisot, and has gone on to influence contemporary artists like Yinka Shonibare, Kent Monkman, and Lisa Yuskavage.

Also rediscovered by the de Goncourt brothers, Watteau's commedia dell'arte subjects influenced Pablo Picasso, Cézanne, and Henri Matisse, as well as many poets such as Paul Verlaine and Guillaume Apollinaire, the composer Arnold Schoenberg, and the choreographer George Balanchine.

The term Rococo and the artists associated with it only began to be critically re-evaluated in the late 20th century, when the movements of Pop Art and the works of artists like Damien Hirst, Kehinde Wiley, and Jeff Koons created a new context for art expressing the same ornate, stylistic, and whimsical treatments. Rococo has had a contemporary influence as seen in Ai Weiwei's Logos 2017 where, as art critic Roger Catlin wrote, "What looks like a fancy rococo wallpaper design in black and white and in gold is actually an arrangement of handcuffs, chains, surveillance cameras, Twitter birds and stylized alpacas - an animal which in China has become a meme against censorship." The movement also lives on in popular culture, as shown in Arcade Fire's hit song "Rococo" (2010).

Useful Resources on Rococo

-

![Soap Bubbles, probably 1733/1734, Jean Simeon Chardin]() 3k viewsSoap Bubbles, probably 1733/1734, Jean Simeon ChardinNational Gallery of Art

3k viewsSoap Bubbles, probably 1733/1734, Jean Simeon ChardinNational Gallery of Art -

![Vigée Le Brun: Woman Artist in Revolutionary France]() 15k viewsVigée Le Brun: Woman Artist in Revolutionary FranceThe Met

15k viewsVigée Le Brun: Woman Artist in Revolutionary FranceThe Met

-

![Music and Theatre in Watteau's Paris]() 22k viewsMusic and Theatre in Watteau's ParisOur PickTalk by Georgia Cowart / The Met

22k viewsMusic and Theatre in Watteau's ParisOur PickTalk by Georgia Cowart / The Met -

![Pageantry of Venice: Canaletto's Portrayals of State Festivals]() 3k viewsPageantry of Venice: Canaletto's Portrayals of State FestivalsTalk by Dawson Carr / Portland Art Museum

3k viewsPageantry of Venice: Canaletto's Portrayals of State FestivalsTalk by Dawson Carr / Portland Art Museum -

![Canaletto: view paintings of Venice]() 118k viewsCanaletto: view paintings of VeniceTalk by Francesca Whitlum-Cooper / National Gallery

118k viewsCanaletto: view paintings of VeniceTalk by Francesca Whitlum-Cooper / National Gallery -

![Colin B. Bailey presents Fragonard's 'Progress of Love']() 43k viewsColin B. Bailey presents Fragonard's 'Progress of Love'The Frick Collection

43k viewsColin B. Bailey presents Fragonard's 'Progress of Love'The Frick Collection -

![Secrets of the Wallace: The Swing by Jean-Honoré Fragonard (1767)]() 56k viewsSecrets of the Wallace: The Swing by Jean-Honoré Fragonard (1767)Our PickCarmen Holdsworth-Delgado / The Wallace Collection

56k viewsSecrets of the Wallace: The Swing by Jean-Honoré Fragonard (1767)Our PickCarmen Holdsworth-Delgado / The Wallace Collection -

![Thomas Gainsborough: The Substance of Style]() 6k viewsThomas Gainsborough: The Substance of StyleBy Frederick Ilchman / WGBHForum

6k viewsThomas Gainsborough: The Substance of StyleBy Frederick Ilchman / WGBHForum -

![Rococo: Chardin and the Ray]() 27k viewsRococo: Chardin and the RayBy Waldemar Januszczak / zczfilms

27k viewsRococo: Chardin and the RayBy Waldemar Januszczak / zczfilms -

![Royal Collection: Charles-Alexandre de Calonne by Elisabeth Vigée Le Brun]() 6k viewsRoyal Collection: Charles-Alexandre de Calonne by Elisabeth Vigée Le BrunBy Jennifer Scott / The Royal Family

6k viewsRoyal Collection: Charles-Alexandre de Calonne by Elisabeth Vigée Le BrunBy Jennifer Scott / The Royal Family

Ask The Art Story AI

Ask The Art Story AI