Summary of Salon Cubism

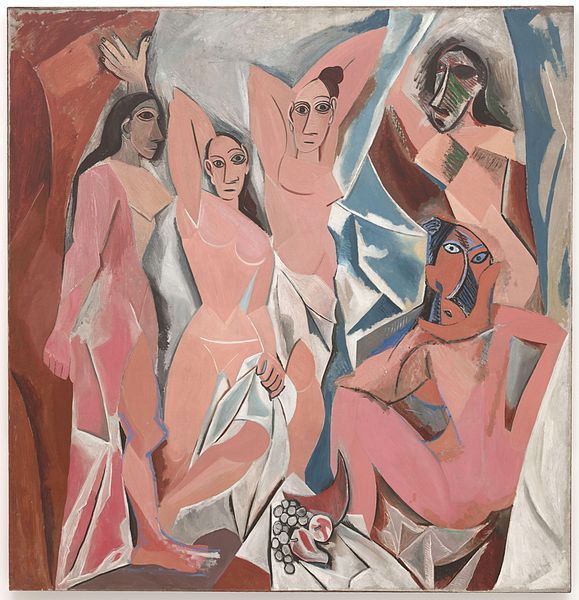

The Salon Cubists, a group of avant-garde French artists, who lived and worked in Paris and its environs, built upon the early Cubist experiments of Pablo Picasso and Georges Braque, but they intentionally steered a different artistic path. Compared to Picasso’s and Braque’s small, intimate works with the subdued palette of browns and greys, Salon Cubists painted large scale works in vibrant colors and grounded their aesthetic theories with references to mathematics and vitalist philosophy.

The term Salon Cubists was adopted following the 1911 Salon des Indépendants to distinguish them from the "gallery Cubists," Picasso and Braque, who showed with the art dealer Daniel-Henry Kahnweiler. While Picasso and Braque are now the most famous Cubists, it was the Salon Cubists who established Cubism as an identifiable movement and introduced it to the general public through their exhibitions in notable Paris Salons between 1910 and 1913.

Key Ideas & Accomplishments

- Picasso and Braque formulated the foundations of Cubism in artistic conversations in their studios; with the stipend provided by their dealer Daniel-Henry Kahnweiler, they were able to experiment out of public view. The Salon Cubists, however, exhibited publicly in the Salons and felt a greater desire to communicate their aesthetic ideas with the public and were more attuned to public reception.

- The idea of simultaneity, or mobile perspective, was a main tenet of Salon Cubism. The goal of the painter was to give the viewer the most information about an object by depicting multiple vantage points at the same time. Eschewing traditional one-point perspective that had ruled Western painting’s depiction of reality, the Salon Cubists depicted reality with fragmented, overlapping, and translucent planes to suggest a higher reality, a fourth dimension. This distortion also suggests that space and form are inextricably bound.

- Simultaneity was also closely linked with Henri Bergson’s notion of duration, or psychological time, which highlighted the subjectivity of experience. Bergson held that consciousness of an object or an experience consisted of "several conscious states...organized into a whole, permeat[ing] one another, [and] gradually gain[ing] a richer content." Salon Cubists encouraged the subjectivity of experience by requiring the viewer to complete, to resolve the various perspectives, into the "total image," as Jean Metzinger referred to it.

- While Salon Cubists helped to move painting further into abstraction, their paintings were never completely abstract. While they still painted portraits and genre scenes, their subject matter tended to be more "epic" and more allegorical, pointing to Cubism’s ability to merge traditional ideals and modern life.

Artworks and Artists of Salon Cubism

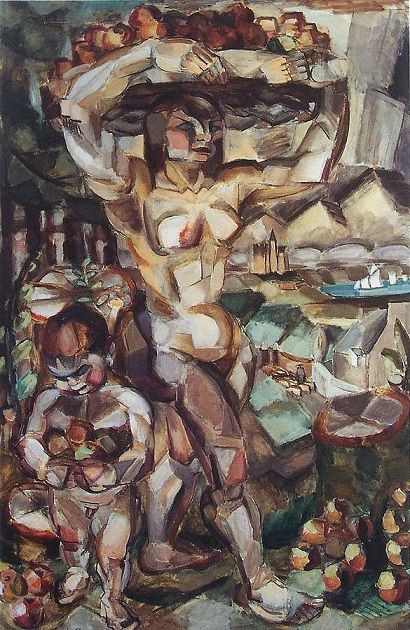

Abundance

Le Fauconnier presents the viewer with an allegory of the plentitude of nature and the fertility of womanhood in the large-scale oil painting. A nude woman bears an oversized platter laden with fruit on her head, and a nude child with his arms full of apples stands next to her. The figures occupy a landscape in which a lake with boats, the spires of a castle, mountains, and a city street can be glimpsed, and the foreground is littered with fallen fruit.

Le Fauconnier does not depict the scene from multiple perspectives as would be typical of Picasso and Braque, but instead he analyzes the volume of the figures and landscape. The faceted bodies of the figures and the landscape convey a common density and weight. While patches of red and blue throughout the composition create movement through the image, the underlying greys and browns further unite the figures and the landscape as seen in the similarity between the woman’s shoulders and arms and the cubic mountains in the upper right of the painting. The figures are meant to embody the earth’s abundance, as if they too had materialized from the same substance.

At the 1911 Salon des Indépendants, Le Fauconnier’s work made him the public face of the new avant-garde art, and his monumental approach to an allegorical subject and his preoccupation with volume and weight were important influences upon Salon Cubism.

Oil on canvas - Gemeentemuseum Den Haag, The Hague, Netherlands

Woman with Phlox

The monochromatic and abstracted treatment of a traditional genre scene created a scandal when it was shown at the 1911 Salon des Indépendants, where viewers thought the painting outlandish. A woman sits in a room between two vases filled with flowers. She concentrates on the unfolded paper or cloth she holds in her lap. Behind her, a window opens onto a view of the landscape beyond. The reductive color palette, combined with the angled planes of multiple perspectives, creates a blurring between the interior of the room and the exterior view and between the figure and her surroundings.

Gleizes felt that the figure was not important in itself but functioned only as a "figurative support," as he wrote, to be "subordinated to true, essential qualities that correspond to the plastic demands of painting." Here, the woman’s clothing and body become cubic volumes, sculpted in cylindrical forms, creating not so much the sense of layered planes of vision, as layered planes of dense materiality. As the art historian, Daniel Robbins has written, "We see the artist's volumetric approach to Cubism and his successful union of a broad field of vision with a flat picture plane." As Gleizes himself wrote, he was most interested in "an analysis of volume relationships," wanting to convey solidity and structure, and it was this emphasis on synthesizing the materiality of the world according to the sensations the artist felt that contributed not only to Cubism but also toward further abstraction.

Oil on canvas - Museum of Fine Arts, Houston, Texas

Woman with a Horse

Metzinger depicts a nude woman, wearing a pearl necklace petting the ear of a horse while her right hand offers the horse a treat. The scene is placed in a landscape, though a window is visible in the upper right of center and a vase and various flowers and fruits are in the foreground. The setting of the woman and the horse is ambiguous. The model’s block upon which the woman sits coupled with the vase in the foreground and what appears to be a window suggests the two are inside, perhaps in the artist’s studio, but the landscape elements in the foreground and what appears to be a tree in the top left indicate that the pair could also be outside.

The large painting embodies Metzinger’s idea of simultaneity, combining different perspectives at the same time. To counter the traditional reliance on Euclidean geometry that formed the basis of traditional linear perspective, Metzinger thought one must look to non-Euclidean geometry and the fourth dimension to depict modern experience. As he and Gleizes were to write in Du Cubisme (1912), "There are as many images of an object as there are eyes which look at it; there are as many essential images of it as there are minds which comprehend it." Furthermore, following the vitalist ideas of Henri Bergson, Metzinger relied on the viewer’s "creative intuition" to contemplate the multidimensional fragments over time in order to create the total image.

The Danish physicist Niels Bohr who received the 1922 Nobel Prize for his work in quantum mechanics and atomic structure eventually owned Woman with a Horse. Bohr hung the painting in his office, and was further influenced by his reading of Du Cubisme (1912). As Arthur I. Miller wrote, Metzinger’s work and thought inspired Bohr "to postulate that the totality of an electron is both a particle and a wave, but when you observe it you pick out one particular viewpoint."

Oil on canvas - Statens Museum for Kunst, Copenhagen, Denmark

The Smokers

This painting, depicting smokers sitting among the tables and chairs at an outdoor café, uses sharply delineated geometric cubes, planes, and cylinders to create a rhythmical and intensely colorful pattern. The curving arcs of the billowing smoke create a dynamic diagonal movement extending to the upper edge of the canvas, while the darkly colored cylinders of fragmented tables and chairs create a busy sense of space. Through the painting’s center, a curved row of green ovoid treetops rises, resulting in an energetic tension between volume and the flatness of the picture plane.

As early as 1910, Leger’s preoccupation with discrete geometric forms, as seen in his Nudes in the Forest (1910), caused his Cubist work to be dubbed "tubism" for its use of cylindrical forms, or tubes. Leger’s Cubism, more than the other artists, entails a dynamism that has much in common with Futurism, and his chosen subject matter of machines, city life, and robot-like human figures made his work unique among the Salon Cubists.

Oil on canvas - The Solomon R. Guggenheim Museum, New York, New York

The City of Paris

Delaunay’s tour de force painting creates a complex, multidimensional view of Paris. Three female nudes in the center, abstracted into small, faceted planes, overlay a landscape that depicts the historic city, with the Quai de Louvre on the left, and modern Paris, with the Eiffel Tower on the right. The city, landscape, and sky above it are broken up by various angles of perception. The overlapping and almost transparent surfaces create a dynamic, even dizzying, surface.

Delaunay painted this work in approximately 15 days for the 1912 Salon des Indépendants, where he and the other Salon Cubists hoped to make a statement. Apollinaire considered La Ville de Paris the most important work of the show, saying, "This picture marks the advent of a conception of art lost perhaps since the great Italian painters... He sums up, without any scientific pomp, the entire effort of modern painting." The monumental size of the painting, 9 by 13 ½ feet, suggests an heroic age, and the figures, inspired by a mural from Pompeii that Delaunay had seen on a previous trip to Italy, reflect the ancient classical tradition as well as the later Neoclassicism that employed mythological subjects in moralizing tableaux. The three women, in a ring with their arms loosely enlaced, symbolize the three goddesses from the Judgment of Paris. Delaunay’s simultaneous depictions, not only of different spatial perspectives but different temporal moments present Cubism as the rightful heir, the culmination, of traditional Western art.

Apollinaire also declared this work an early example of Orphism, a subsequent movement launched by the Delaunays that emphasized simultaneity by relying on color, not form, as the organizing principle. Deeply influenced by color theory, the artist here created planes by the placement of contrasting and complementary colors. This emphasis upon the primacy of color, rather than a breaking up of form, was Delaunay’s most influential contribution to Cubism and informed his subsequent movement to abstraction.

Oil on canvas - Museé National d'Art Moderne, Centre Georges Pompidou, Paris

Architectural façade of the Cubist House

Duchamp-Villon designed the façade of the no longer extant but well-known La Maison Cubiste (Cubist House) for the Art Décoratif section of the Salon d’Or in Paris in 1912. The entrance, eight by ten meters, deploys a Cubist geometric trim with intersecting planes, interlocking rectangles, and cylindrical forms.

The otherwise traditional house, exhibited with a living room and a bedroom, was designed to showcase Cubist art by Albert Gleizes, Jean Metzinger, Marie Laurencin, Marcel Duchamp, Fernand Léger, and Roger de La Fresnaye. The interior designer Charles André Mare worked with the Salon Cubists to create this early example of Art Décoratif. The idea was, as Léger wrote to Mare, that, "People will see Cubism in its domestic setting, which is very important." The house was very influential in advancing the idea of a geometrical vision, rooted in Cubism, but extending to all aspects of modern life. It influenced the architect Le Corbusier in making his Maison Cibrohan, a model for mass production, for the 1922 Salon d’Automne. Viewing the Cubist House at the Section d’Or exhibition, Le Corbusier found in the design significant solutions for building with cement, and Czechoslovakian architect Pavel Janák’s reconstruction of the face of the Fara House in 1913 also drew upon Duchamp-Villon’s geometric forms.

Plaster, wood - Destroyed

Walking Woman

This innovative bronze statue contrasts internal concave volumes with external convex lines by excavating the center of the figure. The negative spaces in the middle of the torso and the head create a dynamic rhythm and a sense of internal form. The human figure becomes an abstract form moving through space, simultaneously viewed from different points of view. Archipenko’s use of negative space revolutionized the approach to sculpture and echoed Leger’s "tubular" Cubist works that contrasted concave and convex form. As Archipenko said, "I did not take from Cubism, but added to it."

Archipenko has been viewed as primarily a Cubist sculptor, and like the others was influenced by the sculpture of Africa and Oceania, but instead of building up solid forms, Archipenko hollowed out the form, leaving voids. Archipenko’s radical approach was more at home among the Puteaux Group and the subsequent Section d’Or, which he joined in 1912. The Italian Futurist Boccioni visited Archipenko’s studio in Paris, as well as the studios of Raymond-Villon Duchamp and Georges Braque, and was particularly influenced by Archipenko’s sculptures, including this one, in the development of his own Futurist style, as exemplified in his Unique Forms of Continuity in Space (1913).

Bronze - Denver Museum of Art, Denver, Colorado

Woman with a Fan

In 1914 Archipenko began making what he called "sculpto-paintings," and Woman with a Fan is the earliest surviving example. The piece is constructed of burlap, linen, metal, and readymade objects like a wooden shelf, a metal funnel, and a glass bottle, all painted in luminous polychrome. The paint creates contrasting and complementary volumes, while at the same time dissolving the materiality of the objects into abstract geometric forms. As Archipenko said, "My painting and sculpture represent a reciprocal connection of form and color. The one stresses or diminishes the other. They are unified or contrasted on the visual and spiritual plane."

This use of bright colors, reflecting the Salon Cubist palette, was a significant innovation in sculpture. As Juan Gris was to write, "Archipenko challenged the traditional understanding of sculpture. It was generally monochromatic at the time... Instead of accepted materials such as marble, bronze or plaster, he used mundane materials such as wood, glass, metal, and wire. His creative process did not involve carving or modeling in the accepted tradition but nailing, pasting and tying together, with no attempt to hide nails, junctures, or seams. His process parallels the visual experience of cubist painting." Archipenko expanded the collage method pioneered by Picasso and Braque with Synthetic Cubism to create a more visually complex object that straddles both painting and sculpture.

Wood, sheet metal, glass bottle and metal funnel - Tel Aviv Museum of Art, Tel Aviv, Israel

The Large Horse

This bronze sculpture depicts a horse in smooth geometric volumes and triangular planes as a synthesis of nature and machine, its internal concavities containing convex mechanized forms. As a result of its Cubist play with volume, the work approaches abstraction. During World War I, the artist served in a cavalry regiment and, during that time, began working on preliminary sketches and models for this work. The earliest show that its inspiration was a horse preparing to jump. Duchamp-Villon was also influenced by the photographic work of Eadweard Muybridge that documented the motion of a horse in a series of still photographs. Duchamp-Villon intended to capture the gathering energy before the horse’s leap with the tension between the solidity of the bronze and the contrasting concave and convex forms that both compress and extend movement.

Duchamp-Villon was a leading member of the Puteaux Group, and his work exemplified the theoretical basis of that movement, rooted in impersonal scientific observation and non-Euclidean geometry. While his work has sometimes been viewed as both influenced by and influencing Italian Futurism, his emphasis upon the mechanistic primarily derives from this sense of mathematical harmony that is present in both machine and nature. As he wrote to his friend, the art historian Walter Pach, "The power of the machine imposes itself upon us and we can scarcely conceive living bodies without it." Duchamp-Villon updated the traditional equestrian statue, not as a monument to generals or kings but as a monument to the utopian promises of the machine.

Bronze - Museum of Fine Arts, Houston, Texas

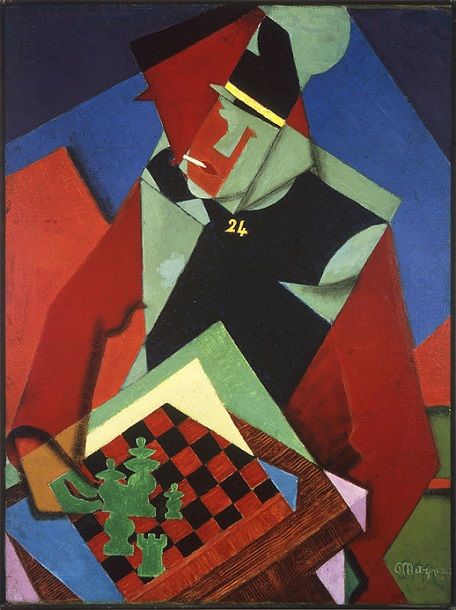

Soldier at a Game of Chess

A soldier, wearing the uniform and the number of the 24th Infantry Regiment, is shown playing a game of chess. The work uses broad overlapping planes of color, depicting the soldier’s head both frontally and in profile, while the chessboard, with its five pieces depicted in profile, is seen from above. The treatment is highly stylized and geometric, eschewing all depth of field, with the result that foreground and background merge into one flat, abstract image. This reductive approach made the work an early innovative example of what came to be called Crystal Cubism, which as the art historian Christopher Green explains was "a move towards order" and a "process of distillation."

Like most of the other Salon Cubists, Metzinger served in World War I. He became a medical orderly beginning in 1915, and this work was painted either before or during his deployment. As Metzinger was often portrayed with a cigarette in his mouth, it’s thought that this may be a self-portrait. Whatever the case, the artist himself wrote to Gleizes, "The End, however, isn't the subject, nor the object, nor even the picture - the End, it is the idea."

Oil on canvas - Smart Museum of Art, Chicago, Illinois

Beginnings of Salon Cubism

The story of Cubism usually begins in the studios of Pablo Picasso and George Braque, who were looking at African sculpture and Paul Cézanne's late landscapes and still lifes, which reduced form to geometric cubes, pyramids, and cylinders. Picasso and Braque took Cézanne’s geometry even further, creating scenes from faceted planes of monochromatic color. There were other artists, however, who were similarly experimenting with form. Jean Metzinger and Robert Delaunay were longtime artistic colleagues who painted in the radical Neo-Impressionist style and were influenced by the color theories of Georges Seurat. Metzinger was also influenced, as were most of the Cubists, by the works of Cézanne, which had been exhibited in major Salons in Paris from 1904-1907. Cézanne’s work became the bridge between Metzinger’s earlier Neo-Impressionist work and his Cubist fracturing of the image into multiple perspectives.

Henri Le Fauconnier also played a leading role in the development of Salon Cubists as he influenced Albert Gleizes first forays into Cubism, as seen in Gleizes’s Portrait of Arcos (1909) with its flat simplified forms and reduced color palette. Gleizes met Le Fauconnier in 1909 and subsequently introduced his friends, Delaunay, Leger, and Metzinger to the artist, and the group often gathered in Le Fauconnier’s studio, hammering out their artistic ideas while Le Fauconnier was working on his signature work Abundance (1910), a large Cubist work depicting an allegorical scene of a nude carrying a large tray of fruit.

Maurice Princet

The Salon Cubists, particularly Jean Metzinger and Albert Gleizes, the leading theoreticians of the movement, were influenced by the mathematical concepts of Maurice Princet. An actuary and amateur mathematician, in 1906 Princet became close friends with Metzinger, as well as other artists like Pablo Picasso, who lived and worked in Bateau-Lavoir. The building in the Montmartre district of Paris became famous for the number of noted writers, intellectuals, and artists who lived and gathered there, and was a hub for the early development of Cubism.

Dubbed "the mathematician of cubism," Princet introduced the Cubists to the idea of the "fourth dimension" via Henri Poincaré’s work and Esprit Jouffret’s Elementary Treatise on the Geometry of Four Dimensions. Jouffret’s text, based upon Poincaré's Science and Hypothesis (1902), described how four dimensional geometric shapes could be created on the two dimensional page by using multiple perspectives. According to the art historian Linda Henderson, the idea of a fourth dimension liberated the artists from depicting reality via one-point perspective and allowed them to reveal a new, higher, reality. As Metzinger wrote of Princet, "beyond his profession, it was as an artist that he conceptualized mathematics, as an aesthetician that he invoked n-dimensional continuums. He loved to get the artists interested in the new views on space...." Princet was so influential upon the development of the movement that the art critic Louis Vauxcelles called him "the father of cubism."

Salon d’Automne (1910)

At the 1910 Salon d’Automne, Jean Metzinger exhibited Nu à la cheminée (Nude) (1910), introducing to the public the radical Cubist style that Picasso, Braque, and others had been developing in their studios. Metzinger, along with Henri Le Fauconnier and Fernand Léger, exhibited in Room VIII of the Salon, and the impact of their work seen in proximity to each other led other artists such as Roger de la Fresnaye and the sculptors Alexander Archipenko and Joseph Csaky to join the ranks of the Salon Cubists.

Nu à la cheminée (also Nu dans un intérieur, Femme nu, and Nu) (Nude) (1910) aroused critical controversy such that the art critic Jean Calud called it a "a puzzle, cubic and triangular...beyond comprehension." However, the poet and art critic Roger Allard praised the "analytical synthesis" of the nude and felt that a new movement of French art, focusing on form, not color, had appeared in the works of Metzinger, Gleizes, Le Fauconnier, and Robert Delaunay.

Metzinger’s article Notes sur la peinture (1910) also introduced the theoretical underpinnings of the new style and became a foundational text, defining the Cubist concept of simultaneity, or mobile perspective. Metzinger explained that artists like Braque, Delaunay, Gleizes, Le Fauconnier, and Picasso allowed themselves "the liberty of moving around objects," and combining that mobile perspective in a single image.

Salon des Indépendants (1911)

The group of artists that coalesced at the previous Salon d’Automne organized to display their works as a group to publicly launch Cubism. They campaigned extensively to suspend the Salon’s rule that required works be hung alphabetically and succeeded in taking over the show from the Neo-Impressionists. Showing in Room 41 at the exhibition, each of the five artists, Delaunay, Leger, Gleizes, Metzinger, and Le Fauconnier, displayed their paintings. At the insistence of the poet and art critic, Guillaume Apollinaire, the artist Marie Laurencin also exhibited with the group.

Le Fauconnier’s Abundance (1910) was singled out for attention, making him "one of the most audacious artists in all Europe and as the originator of a new movement in painting," according to art historian David Cottington. While the painting does not look so daring to our contemporary eyes, especially in comparison with some of Picasso’s work from this time, according to Cottington, Abundance became "the best-known Cubist picture in Europe before 1914" because its allegorical subject in a Cubist treatment seemed to make possible a modern reconfiguration of the French classical tradition.

Room 41, as Apollinaire, said "left a deep impression on the public," and Gleizes characterized the reaction to the show as an "explosion." He wrote, "While the newspapers sounded the alarm to alert people to the danger, and while appeals were made to the public authorities to do something about it, song writers, satirists and other men of wit and spirit provoked great pleasure among the leisured classes by playing with the word ‘cube,’ discovering that it was a very suitable vehicle for inducing laughter which, as we all know, is the principle characteristic that distinguishes man from the animals." The exhibition made Gleizes, Metzinger, Léger and Delaunay, instantly and internationally famous, and the group was dubbed the "Salon Cubists."

The Puteaux Group

In 1911, Gleizes, Metzinger, and Delaunay began meeting in Puteaux, a suburb of Paris, where the artist Jacques Villon, the older brother of the sculptor Raymond Duchamp-Villon and the artist Marcel Duchamp, lived. The three brothers, all then exploring Cubism, became the hub of the group. The Puteaux Group, as it came to be called, also included Le Fauconnier, Sonia Delaunay, František Kupka, Francis Picabia, Juan Gris, Jean Marchard, and the sculptors Joseph Csaky and Alexander Archipenko.

During these gatherings on Sunday afternoon, and the Monday follow-up discussions at Gleizes’s studio in the nearby suburb of Courbevoie, the artists refined the theoretical basis of Salon Cubism and its artistic tenets. As art historian David Cottington explained, their "discussions ranged widely across the philosophies of Bergson and Nietzsche, the social purpose and epistemic status of art, the questions of dynamism and modernity, [but] it was mathematics - or, more narrowly, number and geometry - that provided the intellectual cement that held these considerations together." The emphasis on number and geometry led to Princet giving informal lectures to the group on mathematical concepts, which played a fundamental role in developing their ideas.

The group also favored the "scientific clarity of conception" of Georges Seurat’s Neo-Impressionism that emphasized the impersonal mathematical harmony of painting. Seurat’s noted works, monumental in scale, employed a vibrant color palette based upon his color theory, and the Salon Cubists followed suit, setting their work apart from the intimate and subdued Cubist still lifes and landscapes of Picasso and Braque. As a result, the group was also dubbed the "Epic Cubists."

Section d’Or

Following the public launch of Cubism at the 1911 Salon, the Puteaux Group took up the name Section d’Or, as suggested by Jacques Villon. Meaning "the golden section" or "the golden ratio," the new name emphasized that their Cubism was the final culmination of the Western tradition of the concept of the golden ratio that went back to the ancient Greeks. In coming up with the name, Villon was influenced by his reading of Leonardo da Vinci’s Trattato della Pittura (1651) recently translated into French by Joséphin Péladan.

The group began planning their first exhibit to showcase the vitality of Cubism and to show that it was deeply attuned to the modern era and the culmination of Western art. The 1912 Salon de la Section d'Or took place at the Galerie La Boétie in Paris and exhibited over 200 works by Delaunay, Gleizes, Metzinger, Francis Picabia, Andre Ohote, Marcel Duchamp, Juan Gris, Raymond Duchamp-Villon, Fernand Leger, Louis Marcoussis, and Roger de la Fresnaye. Many of the artists included their earlier works, and the show also became a major retrospective of Salon Cubism and its development.

The exhibition also included an Art Décoratif section, one of the earliest examples of the inclusion of the decorative arts, which showcased La Maison Cubiste (Cubist House,) with its façade designed by Duchamps-Villon. André Mare designed the two interior rooms where paintings like Metzinger’s Woman with a Fan (1912) were displayed in what was called the "Salon Bourgeois." The Cubist House had such an impact that the public subsequently began to refer to anything modern as "Cubist," and Walter Pach, president of the Armory Show in 1913 in New York City, called Duchamps-Villon’s design, "an example of what possibilities are contained in a style like the present one whose philosophy is a base."

Du Cubisme (On Cubism)

In conjunction with the 1912 exhibit, Metzinger and Gleizes published Du Cubisme (On Cubism) (1912), which explained the Cubists’ use of "multiple perspective." By breaking the image into faceted planes, the artists wanted to create an experience of simultaneity and psychological fluidity. As they wrote, "In order that the spectator, himself free to establish unity, may apprehend all the elements in the order assigned to them by creative intuition, the properties of each portion must be left independent, and the plastic continuum must be broken into a thousand surprises of light and shade." In trying to understand the object itself from multiple perspectives, the viewer created the "total image." Art historian Mark Antliff explains that Metzinger and Gleizes incorporated Bergsonian notions of intuition and simultaneity into their understanding of both the artist’s and the viewer’s selves, writing "Thus the Bergsonian notion of simultaneity presented in Du Cubisme is yet another manifestation of the utopian aspirations that pervade the early modernist conception of the artist’s role in society."

On Cubism defined Cubism as a term for the first time and was the first extensive treatise on the theoretical and stylistic foundations of the movement. On Cubism had a great impact on the art world and public consciousness of the movement, as it went through 15 printings in 1912 alone and was published widely in translation, appearing in English in 1913.

Salon Cubism: Concepts, Styles, and Trends

Crystal Cubism

During World War I, Jean Metzinger’s style evolved into what came to be called Crystal Cubism, which came into full flower following the war. Seen as part of the era’s "return to order," the term "Crystal Cubism" originated with the French art critic Maurice Reynal. Metzinger’s Soldier at a Game of Chess (1914-15), with its flat simplified multiple planes of color, emphasizes what the art historian Christopher Green has called the "orderly qualities" and "autonomous purity" of Crystal Cubism’s geometric and abstract structure. The emphasis in Crystal Cubism was on the painting as an object in itself, as Green further described, "a single-minded insistence on the isolation of the art-object in a special category with its own laws and its own experience to offer, a category considered above life."

Metiznger along with Juan Gris, who had been closely associated both with the Cubism of Picasso and Braque and the Salon Cubists, popularized this new style. Works like Gris’s Portrait of Josette Gris (1916) used a simplified, monochromatic palette with overlapping geometric planes. Leger and Gleizes and other Salon Cubists, including the sculptors Laurens and Lipchitz, also gravitated toward Crystal Cubism. Green argues that Crystal Cubism was the most influential form that Cubism took, writing, "In terms of a Modernist will to aesthetic isolation and of the broad theme of the separation of culture and society, it is actually Cubism after 1914 that emerges as most important to the history of Modernism."

Orphism

Though Orphism began around 1911 as the work and theory of Robert and Sonia Delaunay converged with the work of František Kupta, it was officially launched in 1912. Robert Delaunay’s Simultaneous Windows series (1912-1913) and Kupka’s Amorpha: Fugue in Two Colors (1910-1911) exemplified the approach that, as Delaunay wrote, "would depend only on color and its contrast but would develop over time simultaneously perceived at a single moment." The poet and art critic, Apollinaire first used the term Orphism at the 1912 Section d’Or, and as a result, Orphism was seen as a sub-movement, developing out of Cubism. However, Delaunay subsequently was to break with the Puteaux Group and, feeling that his Simultaneous Windows were a major artistic breakthrough, described himself as "the heretic of Cubism." The Delaunays became the major practitioners of Orphism, and, while their work emphasized geometric patterns, often in fractured planes, color and not form was the foundation of the increasingly abstract compositions.

Orphism influenced later artists like Paul Klee in his abstract color shapes and the development of abstraction, in both its geometric and lyrical styles. The Op art of Bridget Riley, Richard Anuskiewicz, and Wen-Ying Tsai were influenced by Orphism’s emphasis upon color to create depth and movement. Sonia Delaunay’s design works, based upon the principles of Orphism, had a wide ranging impact on all fashion and interior design as her Orphic idiom became part of the public consciousness.

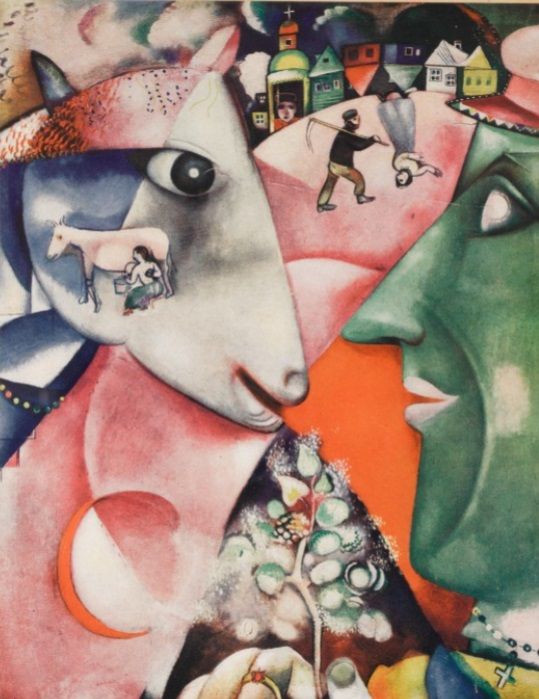

Later Developments - After Salon Cubism

Salon Cubism was very influential from its inception until the outbreak of World War I. In 1912, Le Fauconnier became the head of the Académie de La Palette and recruited Metzinger as a teacher. Marc Chagall, Lyubov Popova, Nadezhda Udaltsova, Serge Charchoune, and Varvara Stepanova were among the students. The sculptor Joseph Csaky also attended the Académie de La Palette and credited the school and his teachers for his turn to Cubism. Even beyond Paris, associations with the Salon Cubists influenced the Moscow Knave of Diamonds exhibitions, beginning in 1910, and the group also influenced Josef Capek, a leader of the Cubist school in Czechoslovakia.

Metzinger’s theoretical writing on Cubism, along with Gleizes’, was to have a long lasting influence. By 1920 Metzinger, Gleizes, and others were creating works that, having dropped all reference to the "fourth dimension," were emphasizing the flat pictorial plane, and the image as an abstract object in itself, independent of any referent, governed only by abstract geometrical structures.

Following the publication of Kahnweiler’s The Rise of Cubism (1920) much of the subsequent focus on Cubism followed his emphasis on the works of Picasso, Braque, and Léger and adopted his terms Analytic and Synthetic Cubism. As a result, the independent work and evolution of the Salon Cubists were often critically overlooked, although the movement has been re-evaluated at different times. In his "Decline of Cubism" (1948) Clement Greenberg argued that "cubism is still the only vital style of our time, the one best able to convey contemporary feeling, and the only one capable of supporting a tradition which will survive into the future and form new artists." He felt that movement had declined, as practiced by French artists since the 1920s, but that the experimentation it exemplified "have at last migrated to the United States."

More recently, a number of art historians like Christopher Green, David Cottington, and Peter Brooke have drawn attention to the significant contributions of Metzinger and Gleizes and the other Salon Cubists. As art historian Peter Brooke wrote in 2000, "A general history of Salon Cubism, however, still needs to be written, a history that could be extended to include the wonderful collective phenomenon which Christopher Green has called 'Crystal Cubism' - the highly structured work of the Cubist painters...who remained in Paris during the war, most notably Metzinger and Gris. An opening up of this early Cubism in all its intellectual fullness would... reveal it as being not only the most radical movement in painting of the past century but, still, the most rich in possibilities for the future."

Useful Resources on Salon Cubism

-

![Picasso Posse: The Mona Lisa of Cubism]() 8k viewsPicasso Posse: The Mona Lisa of CubismOur PickMichael Taylor discussing Salon Cubism and Jean Metzinger’s Tea Time / By Philadelphia Museum of Art

8k viewsPicasso Posse: The Mona Lisa of CubismOur PickMichael Taylor discussing Salon Cubism and Jean Metzinger’s Tea Time / By Philadelphia Museum of Art -

![Picasso Posse: Reasonable Cubism]() 4k viewsPicasso Posse: Reasonable CubismOur PickMichael Taylor focusing on Albert Gleizes’s Man on a Balcony / By Philadelphia Museum of Art

4k viewsPicasso Posse: Reasonable CubismOur PickMichael Taylor focusing on Albert Gleizes’s Man on a Balcony / By Philadelphia Museum of Art -

![Reordering of Reality]() 1k viewsReordering of RealityMichael Taylor on Juan Gris’ Still Life Before an Open Window / By Philadelphia Museum of Art

1k viewsReordering of RealityMichael Taylor on Juan Gris’ Still Life Before an Open Window / By Philadelphia Museum of Art -

![The Great Upheaval: Robert Delaunay's 'Red Eiffel Tower,' 1911--12]() 6k viewsThe Great Upheaval: Robert Delaunay's 'Red Eiffel Tower,' 1911--12By Art Gallery of Ontario

6k viewsThe Great Upheaval: Robert Delaunay's 'Red Eiffel Tower,' 1911--12By Art Gallery of Ontario -

![Simultaneous Contrasts: Sun and Moon by Robert Delaunay Paris 1913]() 35k viewsSimultaneous Contrasts: Sun and Moon by Robert Delaunay Paris 1913By Museum of Modern Art, New York, New York

35k viewsSimultaneous Contrasts: Sun and Moon by Robert Delaunay Paris 1913By Museum of Modern Art, New York, New York

Ask The Art Story AI

Ask The Art Story AI