Summary of Situationist International

The world we live in is governed by unexamined and unrecognized cultural forces, which can only be undone through engineering radically different situations from which to reflect. This was the key concept behind the Situationist International (also known as SI), a group of left-wing artists and activists whose practices were designed to unsettle and disrupt the systems of consumerist homogeneity in late 20th century Western society. Activities like walking the city aimlessly were reimagined as statements against a society that demanded production, and maps were cut up and reassembled to facilitate wandering. Perhaps unusually for a small group of political artists, these ideas corresponded to real and widespread political and social action, most notably inspiring the 1968 protests and rioting in Paris in which Situationist graphics and slogans featured prominently.

Although falling foul of factionalism and disillusionment towards the end of the movement's most active period, SI's disruptive use of culture and commitment to alternative models of interaction between people and their environment was massively influential. Their notion of the "Spectacle" in particular has become a key critical mechanism for understanding advertising and consumerism's impact on our psyches. Elements of SI's activities can be seen in later Punk and Rave subcultures, in political movements like Occupy and Extinction Rebellion, as well as "artivist" activity like "subvertising".

Key Ideas & Accomplishments

- The Situationist International was a radical movement devoted to the disruption and reimagining of the systems which govern everyday life, growing out of several already existing political groups. Like those groups it was anti-capitalist, and left-leaning, but was also committed to the disruption of the hegemonic politics of Europe in the late 20th century through artistic praxis as well as political agitation. Although eventually fracturing, SI provided a blueprint for rebels and artistic dissidents still followed today.

- Situationism valued the decentralization of creation, with artists working in collaboration or under shared names to undermine the notion of the single genius or visionary. This has gone on to be one of the most enduring aspects of their legacy, directly inspiring many artist collectives and groups.

- Architecture and human geography were key influences on the movement and the art that came out of it, with maps in particular offering an opportunity to subvert the way people think about the spaces they move through. By positioning maps as socially agreed (and therefore rarely unbiased) representations of environments, the Situationist practice of cutting them up, ignoring or purposefully misreading them robbed them of their power to govern the way we negotiate the city.

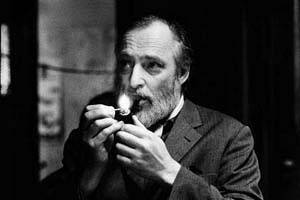

- The notion of "Spectacle", originally outlined by Guy Debord in various Situationist writings, is key to understanding both the conceptual underpinnings of SI and its enduring legacy. The idea of a permanently distracting and preoccupying spectacle, which obfuscates the oppressive nature of capitalism, has been adopted by artists, activists, critics and academics as a key philosophical concept in the current moment of late capitalism.

- Although a collaborative and supposedly open movement, SI adhered relatively rigidly to the direction of Guy Debord and the key ideas and artistic strategies he identified. This is somewhat ironic, as it was actually the wider dissemination and public take up of their ideas that ensured their longevity long after the group fragmented.

Artworks and Artists of Situationist International

Psychogeographique de Paris. Speech on the Passions of Love

This work depicts a city map of Paris, cut into various pieces and rearranged with red broken lines added to create random paths. The work embodies Debord's concept of creating new relations to urban environments. The conventional map, showing planned pathways and routes and place names, is détourned to depict a psychological geography of Paris. The randomness of placement conveys that this 'map' and its structures could be transformed and constantly adapted by the individual's playful and creative behavior. One wanders through this city in the process of dérive between ambient units that have emotional resonance, experiencing the city in a very different way.

Debord's work was a pioneering visualization of his concept of psychogeography, which he defined as "the study of the precise laws and specific effects of the geographical environment, consciously organized or not, on the emotions and behavior of individuals". It influenced the SI's extensive later use of collage and détournement, which included the repurposing of mass media materials like tourist maps. This work also influenced Constant Nieuwenhuys' extensive New Babylon (1956-1974), a series revisioning European cities.

Debord's concept of psychogeography remained a continuing influence into the 21st century. In the 1990s it informed Neoist and other avant-garde academic groups and led to the foundation of The Workshop for Non-Linear Architecture and its programs in London and Glasgow, and the publication of Transgressions: A Journal of Urban Exploration. In the early 21st century Provflux and Psy-Geo-conflux, two experimental action events, developed in the United States in 2003, used psychogeographic maps in various actions. Aleksander Janicijevic, the leader of the Urban Squares Initiative, continues to explore the concept in his artistic practice and in his books, Urbis - Language of the urban fabric (2003) and MyPsychogeography (2015). Recently, a number of phone apps, including Drift, Random GPS, and Derive, have also been developed, to bring the practice of dérive into the digital age.

Lithography, print on paper - Frac Center-Loire Valley France

Letter to my Son

With the spontaneous energy of a child's drawing, loosely sketched and brightly colored figures emerge from a multilayered composition, each of them looking at the viewer with large staring eyes. A dissonance is created between work's vitality and the frenetic, almost anxious expressions of the figures. Referring to Ole, Jorn's son born in 1950, the title also evokes writing, as do the lines as if sketched with a pen or a pencil, conveying a kind of message that David Ebony has described as, "epitomizing the existentialist angst of postwar Europe". At the same time, what Ebony called Jorn's "primal visual language," has a raw celebratory vitality.

When he became artistic leader of Situationist International, Jorn was noted as a founder of the art collaboration CoBrA, but also "a pioneer of European tachiste painting and Art Informel", as Ebony writes. He continued to use many of the same experimental techniques, such as gestural painting and using blotches and stains, to create near abstractions that retained figurative elements and vivid colors while involved with Situationist International. Yet, despite the title's emphasis on writing, the collage effect (as if the disparate figures had been transposed and arranged on a single plane) and the graffiti-like energy of the lines informed SI's artistic praxis from the start. Shown at the 1957 World's Fair in Brussels, this work brought international attention to Jorn and the newly formed Situationist International. Jorn's work was influential, with Ebony writing that his "work seems to presage later developments, like the Neo-Expressionism of Georg Baselitz and Julian Schnabel in the 1980s".

Oil on canvas - Collection of the Tate, United Kingdom

The Change

Using the taches (or stains and blotches) of Tachisme, Rumney's abstract painting creates a vibrant field of mostly primary colors, in which a random and broken grid of black lines emerges. The shapes and grid convey a quasi-geometric effect, and as these traditional forms blur and merge, they form a psychogeographic map of some undefined location or state of mind.

This work was first shown in the 1957 Metavisual, Abstract, Tachiste at the Redfern Gallery in London, the year that Rumney launched the London Psychogeographic Society of which he was the sole member. Spending much time living in Italy and France in the early 1950s, he had become aware and influenced by Debord's concepts. While his first solo show at the New Vision Centre Gallery in London in 1956 made him well-known as part of the international movement toward gestural art, he viewed himself as more connected to a tradition of political dissent, inspired by Surrealism. In his catalogue statement, Rumney wrote, "An act of creation must be autonomous and independent of the creator...The power of a work of art rests in its subject. The subject is independent of all formal qualities and becomes a violent and powerful entity in its own right".

Oil paint, household paint and metal leaf on hardboard - Collection of the Tate, United Kingdom

Industrial Painting

This work is an abstract and gestural painting over 250 feet long. As the painting is unrolled from its wooden spool, the canvas's swirls and blotches of light blue and green, yellow, bright pink, and black are suggestive of figures and buildings in their vibrancy. As only some thirty feet can be displayed at once, experiencing the work becomes a kind of journey, unfurling each view that leads playfully into another.

Pinot-Gallizio made this work with his "painting machine", which he attached mechanical rollers to long tables to create. As art historian Catherine Wood writes, the work "utilised the artist's scientific knowledge alongside technology associated with mass production to create something that was, in contrast to the usual application of these processes, chaotic and entirely unique. "

A trained chemist, Pinot-Gallizio met Asger Jorn in 1955, and they subsequently launched the Experimental Laboratory of the Imaginist Bauhaus in Pinot-Gallizio's studio in Alba, Italy. A number of artists and writers including Walter Olmo, Enrico Baj, Piero Simondo, and Elena Verrone experimented and collaborated in the laboratory, as Baj experimented with what he called 'nuclear art,' and the composer Olmo developed his "tereminofono", an experimental electronic instrument derived from the theremin. Pinot-Gallizio's development of industrial paintings was championed by Debord as a radical technology where art could be combined with industrial processes to consistently create new creative situations. Pinot-Gallizio's innovations extended to collaboration and marketing, his "numerous collaborators including other artists and children...[applied]...the paint with particular gestures prescribed by Gallizio...Following this alternative mode of production, Gallizio's paintings were sold by the metre in the street market of Alba as well as in commercial art galleries", as Wood writes.

Aside from this work, Pinot-Gallizio's other major work was Cavern of Anti-Matter (1959). Shown in Paris, Cavern of Antimatter was a complete immersive environment, with the industrial painting used to cover the ceiling, walls, and floor of the exhibition space at the Galerie Drouin to create what the artist described as an "antiworld". The exhibition helped establish Situationist International as a cultural and artistic force in Paris. The artist's works have been viewed by some critics as precursors of Environmental art and Happenings, and has received renewed contemporary interest since it was shown at the 2008 Sydney Biennial and at the Museo Centro de Arte Reina Sofia, Madrid in 2010.

Monoprinted oil and acrylic paint and typographic ink on canvas - Collection of the Tate, United Kingdom

Le canard inquiétant (The Disquieting Duckling)

A gigantic duckling, its body and head a swirl of neon colors, impasto paint and thick vigorous lines, towers above a cottage on the bank of a quiet pond. The title is apropos, as the almost Godzilla-like duckling disturbs the traditional pastoral scene with orange paint dripping from its beak, the landscape disappearing in a sickly green on the right, and yet the creature is also exuberant as if spontaneously painted by a child. Alluding to Hans Christian Andersen's fairytale, "The Ugly Duckling," about a swan raised by a family of ducks, the work reflected Jorn's sympathy with those displaced by the dominant social system, echoing Michèle Bernstein, a leading critic and cofounder of the movement, who declared, "monsters of all lands unite!".

The innovative artistic leader of Situationist International, Jorn pioneered works like this one, which he called "modifications". As art historian Karen Kurczynski describes, Jorn added "grotesque imagery or abstract painted or dripped additions to amateur academic-style paintings found in flea markets". As Jorn wrote when the work was first exhibited at the Galerie Rive-Gauche in 1959, "In 1939 I wrote my first article ("Intime banaliteter" [Intimate banalities] in the journal Helhesten) in which I expressed my love for sofa painting, and for the last twenty years I have been preoccupied with the idea of rendering homage to it". He intended to "erect a monument in honor of bad painting. Personally, I like it better than good painting...It is painting sacrificed".

The Galerie Rive-Gauche catalog began with Jorn's statement, "INTENDED FOR THE GENERAL AUDIENCE, READ EFFORTLESSLY...If you have old paintings, do not despair. Retain your memories but détourn them so that they correspond with your era." As he explained, "Détournement is a game born out of the capacity for devalorization. Only he who is able to devalorize can create new values." Jorn's "modifications," while exemplifying painterly détournement also pointed toward his next artistic evolution, in 1961 he left the Situationist International and founded the Scandinavian Institute of Comparative Vandalism in Silkeborg, Denmark, focused on researching the culture of Scandinavia in the Viking era.

Scorned by the general audience at the time of their exhibition, Jorn's modifications influenced Alexis Smith, Jim Shaw, and Enrico Bai, and subsequent artists, including Lee Krasner, who détourned her own work by cutting up a previous painting and rearranging the pieces. Jorn's modifications also influenced conceptual artists, including Lorna Simpson, Gran Fury, Tania Bruguera, and Sherri Levine, and, more recently, Betty Thompkins in her Women Words series (2017-18).

Oil on canvas (older painting) - Museum Jorn, Silkeborg, Denmark

Mémoires

This double page of a sketchbook collages fragments of text taken from a variety of sources and a black and white cartoon where a lecturer points to a white empty screen. Superimposed on the text, blotches and drips of bright purple and pink paint disrupt its meaning with a gestural dynamism. At times, as the purple dots are clearly connected by lines, a sense of a random network is created that becomes an explosion of pink on the right. Jorn dripped, dropped, and sometimes painted with the tip of a matchstick to create this vigorous fluidity. At the top of the right-hand page, the phrase, "HOWLING IN FAVOR OF," references Debord's film, Hurlements en Faveur de Sade (Howling in Favor of Sade). Using no images, this 1952 experimental film displayed a white screen when people were talking on its soundtrack and a black screen during long pauses of silence. It began with Debord's statement, "Cinema is dead. Films are no longer possible. If you want, let's have a discussion". This particular image is a representative excerpt from the material that fills the entirety of the book.

Jorn divided the 64 pages of the sketchbook into three sections, called structures portantes, or architectural load-bearing structures, in order to recount Debord's philosophical autobiography as he founded the Lettrist International. Titled "June 1952," the first section begins with a Karl Marx quotation, "Let the dead bury the dead, and mourn them.... our fate will be to become the first living people to enter the new life". The text and images throughout were taken from mass media sources and included photographs, cartoons, city maps, all arranged to drift over the page, as the collage superseded conventional page orientation. The reader wanders through the book in a process of dérive, wandering through the book as one might wander through an environment.

The book was also famous for its jacket, made out of sandpaper, an idea that originated in a conversation between Jorn and V.O. Permild, the printer, who related: "Long had [Jorn] asked me, if I couldn't find an unconventional material for the book cover. Preferably some sticky asphalt or perhaps glass wool. Kiddingly, he wanted, that by looking at people, you should be able to tell whether or not they had had the book in their hands. He acquiesced to my final suggestion: sandpaper (flint) nr. 2: 'Fine. Can you imagine the result when the book lies on a blank polished mahogany table, or when it's inserted or taken out of the bookshelf. It planes shavings off the neighbor's desert goat". This idea of a cultural product that destroys the others around it would later inspire Peter Saville, the lead designer for Factory Records, to use sandpaper on the record sleeve of the album The Return of the Durutti Column (1980). Other artists have created similar homages to Jorn's original work.

Debord and Jorn had previously collaborated on Fin de Copenhague (1957), described by art historian Sylvie Lecoq-Ramond as "the denunciation of the consumer society, an attack against the established values of the avant-garde." When the book was published Architectural Review called it a "remarkable piece of improvisation among the techniques of graphic reproduction" and praised its indifference to the "sacred rituals of printing". As art critic Rick Poynor noted, the "startling layouts (using found material) anticipate, by 30 or more years, the typographic and textual fragmentation of Cranbrook, CalArts and Ray Gun magazine, which became a global design phenomenon".

Illustrated Book - The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York

New Babylon/Sevilla TRIANA-GROEP (New Babylon/Seville TRIANA-GROUP)

In this work, Constant has superimposed the designs for his project of an anti-capitalist city, New Babylon, over a commercially available ink and watercolor map of Seville, Spain. The irregular sized rectangles, which outline structures and pathways in black and red ink, create a kind of wandering grid over the map, their random divergences evoking the path of one roaming the city. The transparency of the superimposed forms reflects the artist's concept for the city - "New Babylon is a gigantic labyrinthine complex raised above the earth on tall pillars. All forms of transport circulate below it. The various tiers of the city can be reached via lifts and stairs and are almost entirely roofed-in and climate-controlled. With their many levels and terraces, they form a vast multi-layered space that constantly offers new surprises as a result of its functional flexibility, climatic variability and light and sound effects. New Babylonians can wander around like modern nomads, in search of new experiences and unknown sensations".

The Dutch born Constant became friends with Asger Jorn in the postwar period and the friendship between the two began an important element of the founding of the CoBrA movement. In 1956 Asger Jorn invited Constant to Alba, Italy, where Constant presented "Demain la poésie logera la vie" (Tomorrow poetry will house life) - his vision for a new architecture that would sustain and inspire a creative lifestyle. In 1957 he began working on the New Babylon series (1956-74); as art critic Nina Siegal wrote, "He spent the next two decades absorbed in this vision, which he expressed through a variety of media, including architecture, sculpture, furniture design, photography, geographical maps and philosophical writings."

He first showed work from the series in a 1959 exhibition at the Stedelik Museum in Amsterdam, where it was met with acclaim. However in 1960 Constant left the Situationist International because he felt it was driven, less by common goals, then by individuals pursuing their own interests. As Nina Siegal writes, "his vision rested on the birth of a new kind of human. Freed from work by anticipated automation of all kinds of production, people would become more playful, experimental and less bound to traditional home and work spaces...These future creative types would need more flexible working and living spaces, and they'd develop new kinds of social networks to enable them to share resources".

Ink, paper - Museo Reina Sofia, Madrid, Spain

"Sous les pavés, la plage!" ("Under the paving stones, there is a beach!")

In this photograph the Situationist phrase "Sous les pavés, la plage!" ("Under the paving stones, there is a beach!") is seen written in large black letters which extend along the sidewalk, just above street level, as three women walk by. During the May 1968 uprising in Paris, thousands of students tore up the streets, using the paving stones to build barricades and discovering the stones had been originally placed on sand. The phrase became a rallying cry, advocating for the dismantling of the social system in order to live a free and unregimented life, symbolized by the underlying "beach." As historian Sadie Plant wrote, the expression "captured both the tactics of the revolutionaries, for whom the cobblestones provided the most obvious weapons against the police, and the symbolic meaning of this détournement of the streets," while "Anonymous, cheap, and immediate, the use of graffiti...epitomized the avant-garde dream of art realized in the practice of everyday life."

Perhaps the most famous of all Situationist International works, the phrase became ubiquitous throughout Paris, written on walls, streets and signs by any number of anonymous artists and students. Bernard Cousin, a student activist, and Bernard Fritsch, who had previously worked in advertising and public relations before becoming a Situationist known as Killian, created the phrase for the movement on May 22, 1968. As Cousin explained, "We wanted to create a graffiti on which we would agree, him, the revolutionary and Parisian situationist and I, the bourgeois Catholic and provincial."

The phrase resonated culturally, shaping French society and politics into the 21st century. Speaking of the challenges facing a new generation in France in 2008, Cousin explained, "The pavement represents our buildings, the roads, the road surface and what we build around it, if we tear it off it is because we no longer understand its layout and its utility, we no longer understand the plan...The beach is much older, it is under and it is before the pavement. It is quite possible that before climbing the dune to explore the vast world we have lived a few million years as semi-aquatic mammals. The total happiness of the child wading at the edge of the water, our evocation the evening when we created the graffiti, could be our paradise lost, that would explain many things of the body of the man and his behavior. It's up to you, young people to explore now."

Graffiti - Paris, France

Beginnings of Situationist International

From the Italian "Internazionale Situazionista," the Situationist International is often also referred to as Situationism. "Situationism" as a name refects the group's emphasis on the "construction of situations", as they created environments that they believed would facilitate revolutionary change. Influenced by Dada, Surrealism, and Marxism, the movement, as art critic Mary Joyce wrote, "combined satire, scandal, and performance to critique consumer society and the routine nature of everyday modern life - at a time when this approach was unusual and profoundly disruptive". They also emphasized misappropriation, taking images and text from mass media to create collages, posters, and brochures, as well as misappropriating amateur and academic paintings for disruptive and revolutionary effect. A collaborative approach was often taken, reflecting the movement's view that art belonged to everyday life and any individual could produce art as it was the process of making that was important to emphasise rather than the concept of "the artist."

Situationist International began at the United Congress of Free Artists in Alba, Italy in 1957. It formed out of an alliance of the International Union for an Imaginist Bauhaus, founded by the Danish artist Asger Jorn, the Lettrist International founded by French philosopher Guy Debord, and the London Psychogeographical Association, founded by British artist Ralph Rumney. Therefore, although the movement was launched in Italy, it was an explicitly international endeavor from the beginning. Other founding members included Dutch artist Constant Nieuwenhuys (also known simply as Constant), architect Attila Kotanyland, French writer Michèle Bernstein, Italian-Scottish writer Alexander Trocchi, and the Italian chemist and artist Pinot-Gallizio, among others. While Jorn led the movement artistically, Debord was its leading theorist. His concepts of psychogeography, dérive and détournement, as well as his view that the existing social system was based upon the "spectacle" and the "commodity", informed the group's mission to create a new artistic paradigm in the early 1960s.

Though contemporaneous with Fluxus and Happenings, both of which sought to remove the line between art and life by creating performances and environments that challenged traditional definitions of art, Situationist International differed in its political emphasis. Until its disbanding in 1972, the movement attracted over 70 international artists, writers, and intellectuals, though membership at any one time was often small and members often left or were expelled from the group due to artistic and political disagreement with Debord and the other leaders.

Guy Debord and Lettrist International

In 1950 at the age of nineteen, Guy Debord joined the Lettrist movement in France. Taking its name from "lettrie," or letters, which were viewed as pure form devoid of semantic meaning, Lettrism was founded by Isidore Isou, a Romanian artist and poet who moved to Paris in the mid-1940s. Influenced by Dada and Surrealism, Isou emphasized combining poetry with graphics and experimental film to create controversial juxtapositions.

When Debord joined the movement in 1950, he was part of a new generation that brought a greater emphasis on left-wing politics to the movement. That same year, Lettrism became notorious when Michel Moure, one of its members, dressed as a monk and took to the pulpit at Easter mass in a Parisian church, giving a sermon announcing the death of God. As the event was broadcast on French national television, a national and international outcry followed, and the movement became widely known. Many figures in the avant-garde, including André Breton, the founder and leader of Surrealism, defended the artist.

In 1952 Debord directed his first film, Hurlements en faveur de Sade (Howling in Favor of Sade) (1952). It consisted of an alternating black and white screen, with the voices of Michèle Bernstein, Debord's first wife, and French artist Gil Wolman heard on the soundtrack whilst white was displayed with black during silent pauses. Met with scorn by audiences, the film nevertheless made Debord a leading figure of the Lettrist movement, At the same time, wanting to emphasis left wing activism, Debord, alongside Wolman, Bernstein, Jean-Louis Brau, and Serge Berna broke with the Lettrists to found the Lettrist International in 1952. As he wrote the "situationist minority first emerged as a tendency in the Lettrist left wing, then in the Lettrist International which it ended up controlling". From that point on, Debord focused his energy on creating an international movement for revolutionary change.

Asger Jorn and the International Union for an Imaginist Bauhaus

The Danish artist Asger Jorn first became known as a co-founder of CoBrA in 1948. The movement, made up of cofounders Karel Appel, Constant and Christian Dotrement, among others and taking its name from their home cities of Copenhagen, Brussels and Amsterdam, emphasized artistic spontaneity with the desire to express "our refound freedom" (as its manifesto declared). The movement ended in 1951 as some members, including Jorn and Constant, embraced a more active political stance. In 1953 Jorn began working in clay and travelled to Albissola, a pottery-making center in Italy where he established a ceramics workshop in the nearby town of Alba, and began to organize an international arts festival. He subsequently divided his time between his residence in Switzerland and his workshop in Italy. That same year, he wrote of his intention, "In the name of experimental artists...to create an International Movement For An Imaginist Bauhaus." Emphasizing the imagination, Jorn's proposal was a refutation of the new Ulm School of Design in Germany, where Swiss architect Max Bill restructured the Bauhaus model but with an emphasis on technical instruction alone. Jorn, along with Piero Simondo, and Giuseppe Pinot-Gallizio, founded the International Movement For An Imaginist Bauhaus in Alba, Italy in 1955.

First World Congress of Free Artists

When Jorn organized the First World Congress of Free Artists in Alba in 1957, he invited Guy Debord and Michèle Bernstein, whom he had contacted several years previously after encountering Potlatch, the bulletin of the Lettrist International. British artist Ralph Rumney, who had recently formed the London Psychogeographical Association, also attended the gathering. At the time, Rumney spent most of each year living in Venice, where he was romantically involved with Pegeen Vail Guggenheim, the daughter of noted modern art gallerist and collector Peggy Guggenheim. At the Congress, Jorn's International Movement For An Imaginist Bauhaus, Debord's Lettrism International and Rumney's Association entered into an alliance to form the Situationist International.

In his Report on the Construction of Situations (1957), the manifesto of the movement, Debord wrote that "Our central idea is the construction of situations...We must develop a systematic intervention based on the complex factors of two components in perpetual interaction: the material environment of life and the behaviors which that environment gives rise to and which radically transform it". Accordingly, the late 1950s were given over to the creation of an artistic revolutionary praxis (applying theory and philosophy in everyday life), as the SI began staging interventions in the art world. In 1958 they "raided" a Belgium art conference by dropping pamphlets and using extensive media coverage to critique the social system of the art work.

That same year Jorn's book Pour la forme (For Form) (1957), which defined his artistic theories and preoccupations, and gave the movement artistic direction. He also collaborated with Debord on the book Fin de Copenhague (End of Copenhagen) in 1957. Simultaneously Jorn's painting Lettre à mon fils (Letter to My Son) (1956-57) increased his internationally profile when it was exhibited at the World's Fair in Brussels, drawing others to the movement that he was closely associated with.

On the Poverty of Student Life

In the early 1960s the founding group began to splinter, with both Jorn and Constant having left the group by 1961. In 1962 Debord argued that art should no longer be emphasized, but be subsumed into a single unified revolutionary praxis. As a result, the movement focused on political actions and the Situationist International became a leading force of social protest, often centered in universities throughout Europe and most influentially in Germany and France. In 1966 five University of Strasbourg students collaborated with the movement to create a critique of student life at the university and published On the Poverty of Student Life: A Consideration of Its Economic, Political, Sexual, Psychological and Notably Intellectual Aspects and of a Few Ways to Cure It (1966). The pamphlet noted how "the student is the most universally despised creature in France", while challenging "leftist intellectuals...[who] go into raptures over the supposed 'rise of the students'" while seeing both that contempt and concern as "rooted in the dominant reality of overdeveloped capitalism". The Strasbourg students held a ceremony where they distributed some 10,000 copies with much fanfare. A local newspaper called the pamphlet "the first concrete manifestation of a revolt aiming quite openly at the destruction of society", and national and international attention quickly followed. The pamphlet became the de facto handbook for student protest throughout Europe, and the SI became a primary source of inspiration for the student uprising in Paris in May 1968.

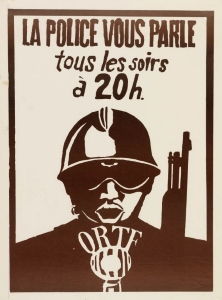

May 1968 Uprising and Atelier Populaire

The student uprising of May 1968 began with a protest at Nanterre University in the first week of May, but within two weeks had spread to over a million people protesting in Paris, followed by a national worker strike. Students, teachers, and Situationist International members occupied the École des Beaux Arts on May 16th and started the Atelier Populaire, or popular workshop, where they produced silkscreen posters. The Atelier called the posters, "weapons in the service of the struggle... an inseparable part of it. Their rightful place is in the centres of conflict, that is to say, in the streets and on the walls of the factories". As art historian Peter Wollen notes, "their [SI's] contribution to the revolutionary uprising was remembered mainly through the diffusion and spontaneous expression of situationist ideas and slogans, in graffiti and in posters... as well as in serried assaults on the routines of everyday life." The revolt in Paris became a leading inspiration of the many protests throughout the world in 1968, from the civil rights and anti-war protests in the United States to protests against state authoritarianism in the Soviet Bloc.

Concepts and Styles

Psychogeography and Dérive

Debord defined psychogeography in 1955 as "the study of the precise laws and specific effects of the geographical environment, consciously organized or not, on the emotions and behavior of individuals." His concept was influenced by Ivan Chtcheglow's "Formulaire pour un urbanisme nouveau" ("Formula for a New Urbanism") (1953). Debord advocated for, "active observation of present-day urban agglomerations, "to discover how environments effected the behavior and feelings of individuals and, conversely, how to make new environments that created the possibility for "a new mode of behavior." The concept encouraged experimentation in all aspects of art and architecture, as seen in Constant's decades long work on New Babylon (1957-74), a reconfiguration of urban environments to allow for creativity and play.

Influenced by the 19th century French poet Charles Baudelaire's concept of the flâneur, a kind of dandy who wandered the city, dérive, or drift, was defined by Debord as, "the practice of a passional journey out of the ordinary through a rapid changing of ambiences." The concept, which was also called Situationist drift, was an essential component of psychogeography, as a place was 'mapped' by individuals wandering freely through the urban environment and finding their own ambient sites. Debord's Psychogeographique de Paris. Speech on the Passions of Love (1957), reconfiguring a map of Paris as a number of disparate but ambient units connected by random paths, was a visual representation of both concepts. His collaborations with Asger Jorn on books like Fin de Copenhague (End of Copenhagen) (1957) similarly approached the book as if it were a kind of environment through which the reader could wander, as words and energetic drips of paint drifted across the page. Ralph Rumney's The Leaning Tower of Venice (1957), was hailed by Debord as, the "first exhaustive photographic work applied to urbanism," as Rumney combined text and photographs to create a psychogeographic Venice.

Détournement

Guy Debord's concept of détournement emphasized superimposing revolutionary content on mainstream images and text to subvert commodity capitalist culture. In the User's Guide to Détournement (1956) Guy Debord and Gil Wolman wrote: "The literary and artistic heritage of humanity should be used for partisan propaganda purposes...Since opposition to the bourgeois notion of art and artistic genius has become pretty much old hat, [Marcel Duchamp's] drawing of a mustache on the Mona Lisa is no more interesting than the original version of that painting. We must now push this process to the point of negating the negation". The most frequent use of détournement was described by Wolman and Debord as using "an element which has no importance in itself and which thus draws all of its meaning from the new context in which it has been placed. For example, a press clipping, a neutral phrase, a commonplace photograph". As the movement stated, "There is no Situationist art, only Situationist uses of art". The emphasis upon misappropriation informed the SI's emphasis upon collage in artworks and in the group's many posters, brochures, and graffiti, most of which were produced anonymously and collaboratively, further challenging the notion of a single and inspired "artist".

Spectacle

Debord defined "spectacle", as "not the domination of the world by images or any other form of mind-control but the domination of a social interaction mediated by images". His book Society of the Spectacle (1967) in particular was ground-breaking and widely influential. In it he argued that "all real relationships having been replaced by that of relationships with commodities, and where commodities have a life of their own". Détournement, derive, and psychogeography were seen as ways to intervene in the spectacle, which he viewed as the dominant social mechanism in the West. As he wrote, "The spectacle epitomizes the prevailing model of social life...In form as in content the spectacle serves as total justification for the conditions and aims of the existing system." Situationist International constructed interventions, whether raiding an art exhibition in Belgium, or expressed in Debord painting, "Ne travaillez jamais," "Never Work" on a wall on the Rue de Seine. Though he painted the slogan in 1953, he considered it central to his life and philosophy throughout the SI period.

Unitary Urbanism

In 1956 Gil Wolman defined "Unitary Urbanism", saying that "the synthesis of art and technology that we call for - must be constructed according to certain new values of life, values which now need to be distinguished and disseminated". Debord and the Situationist International further developed Wolman's concept by defining unitary urbanism as a rejection of any separation between art and the environment, undermining the traditional emphasis on function in architecture in particular. They advocated for a utopian society where the emphasis would be upon the possibilities of creative play and structures would be constantly adaptable to the new configurations created by individuals and groups.

Later Developments - After Situationist International

Situationist International essentially came to an end due to revolutionary disappointment. During the May 1968 uprising, disputes over political strategies and goals broke out between various revolutionary groups. Marxists viewed the popularity of SI's subversive posters and détourned comic strips as deriving from the bourgeois hope to reform the capitalist system, using slogans like "Take your desires for reality," to bypass the need for fundamental structural change. Daniel Cohn-Bendit, known as Danny the Red, who led the student revolt in Paris, attacked Debord as a mere "intellectual agitator" who created chaos with no true commitment to the goals of the new left. Essentially many of the disputes were driven, as historian Sadie Plant wrote, by "the confusion between the appearance and the reality of political commitment compounded by the indeterminate nature of the forces they were trying to overthrow".

At the end of May, French President Charles de Gaulle dissolved the National Assembly, promised to hold elections on June 23rd, and ordered striking workers back to work. Despite initial resistance, most of the workers eventually returned to their jobs, and the revolution that had seemed imminent failed. In the aftermath, Situationist International fragmented as Debord went to Italy and those involved in the protests turned away from the movement to explore new approaches to social change. At the same time, the movement's ideas were absorbed into wider French culture. As Plant wrote, "If the tactics of détournement were present in the events, elements of recuperation peppered their aftermath. Thousands of accounts and explanations of the successes and failures of 1968 appeared in the following two years, collections of posters and photographs were published, and legend has it that souvenir cobblestones were on sale within days of the rioting." Situationist International formally dissolved in Italy in 1972 with Guy Debord and Gianfranco Sanguinetti as its only two remaining members.

Legacy

Situationist art influenced both contemporary artists and subsequent generations of artists. Pinot-Gallizio's industrial paintings, installed as an immersive environment, were seen as precursors of environmental art and happenings, for example. Jorn's repurposing of images influenced Alexis Smith, Jim Shaw, Enrico Bai, Lee Krasner, Lorna Simpson, Gran Fury, Tania Bruguera, Sherri Levine and Betty Thompkins. His collaborative books with Debord influenced later global design's use of what art critic Rick Poynor called, "typographic and textual fragmentation".

Constant Nieuwenhuys' work on the concept of the anti-capitalist city "New Babylon" was informed greatly by Situationism, and led to later developments including the founding of The Workshop for Non-Linear Architecture (with programs in London and Glasgow in the 1990s), and the launching of Transgressions: A Journal of Urban Exploration, a publication devoted to post-avant-garde theories on urban environments.

Ralph Rumney's London Psychogeographical Association was revived in the1990s by Fabian Tompsett as the LPA East London Section and, in conjunction with the revival, the Luther Blissett Project was created, a multiple-use name shared by musicians and artists in the 1990s directly influenced by Situationist ideals of decentralized creation. Subsequently the group collaborated with the Neoist Alliance and eventually created the New Lettrist International.

Situationism heavily influenced Performance and Installation art, particularly the Fluxus Group and Neoism, and the artist Mark Divo. In the early 21st century Provflux and Psy-Geo-conflux, two experimental action events, developed in the United States and used Situationist drifts and psychogeographic maps to create interventions. Aleksander Janicijevic, the leader of the Urban Squares Initiative, continues to explore the concept in his artistic practice and in his books, Urbis - Language of the urban fabric (2003) and MyPsychogeography (2105).

The Situationist concept of the spectacle and its analysis influenced later television programming, particularly in France and Italy, as seen in Carlo Freccero's Italia I and Antonio Ricci's Striscia la notizia in the 1990s. The movement's style and slogans were also adopted by 1970s punk rock music and informed the work of Malcolm McLaren, Jamie Reid, Tony Wilson's Factory Records, and the Feederz. Rock criticism in music publications (such as NME and Sounds) also helped to introduce Situationist concepts to a music audience, as remembered and discussed by Mark Fisher in his recent work. Greil Marcus's influential book Lipstick Traces: A Secret History of the Twentieth Century (1989) explicitly connected the Sex Pistols and punk music to Situationist International and the May 1968 uprising. However, many punk musicians resisted the connection, with John Lydon (also known as Johnny Rotten and lead singer of the Sex Pistols) remarking, "if the secret history of punk rock is situationism then it's so secret nobody told us". The movement has also been seen as an influence upon other musicians, including Laetitia Sadier, Chumbawamba, David Bowie, and Nation of Ulysses, and the 1990s hardcore punk of Orchid, CrimetheInc, and His Hero is Gone.

Debord's concepts also influenced informed subsequent anarchist movements, including King Mob in the UK, and The Weathermen and Rebel Worker in the United States. Anarchist theorists Hakim Bey, John Zerzan, and Fredy Perlman and magazines like Anarchy: A Journal of Desire Armed and Fifth Estate, which drew upon Debord's theories in the 1980s. Later adaptations of his concepts included hacker e-zines like samizdat and groups like Adbusters and Reclaim the Streets that détourn advertising and construct 'situations'. In the digital age, a number of phone apps, including Drift, Random GPS, and Derive, have also been developed, as a way of experiencing Situationist drift. The movement's pioneering use of political graffiti to critique commodity culture has been seen by scholars and critics as setting the groundwork for many subsequent artists, including graffiti artist Banksy.

Ask The Art Story AI

Ask The Art Story AI