Summary of Street and Graffiti Art

The common idiom "to take to the streets" has been used for years to reflect a diplomatic arena for people to protest, riot, or rebel. Early graffiti writers of the 1960s and 70s co-opted this philosophy as they began to tag their names across the urban landscapes of New York City, Los Angeles, and Philadelphia. As graffiti bloomed outward across the U.S., Street Art evolved to encompass any visual art created in public locations, specifically unsanctioned artwork.

The underlying impetus behind Street Art grew out of the belief that art should function in opposition to, and sometimes even outside of, the hegemonic system of laws, property, and ownership; be accessible, rather than hidden away inside galleries, museums, and private collections; and be democratic and empowering, in that all people (regardless of race, age, gender, economic status, etc.) should be able to create art and have it be seen by others. Although some street artists do create installations or sculpture, they are more widely known for the use of unconventional art mediums such as spray paint, stencils, wheat paste posters, and stickers. Street Art has also been called independent public art, post-graffiti, and guerilla art.

Key Ideas & Accomplishments

- A central aspect of Street Art is its ephemerality. Any unsanctioned public work runs the risk of being removed or painted over by authorities or by other artists. No one can own it or buy it. Viewers are seeing a one-of-a-kind work that is likely not to last. This temporariness creates an immediacy and electricity around the work.

- Street Art can often be viewed as a tool for promoting an artist's personal agenda surrounding contemporary social concerns, with city facades acting in the same role as the old fashioned soapbox; a place to extol the artist's opinion on a myriad issues ranging from politics and environmentalism to consumerism and consumption.

- Many street artists use the public canvas of buildings, bridges, lampposts, underpasses, ditches, sidewalks, walls, and benches to assure their individual messages are seen by a wide swath of the population, unfiltered by target demographics or being accessible only to art world denizens.

- As advertising infiltrates, the communal consciousness on a constant daily basis, Street Art has oftentimes been coined a counter attack. Popular street artist Banksy has said, "To some people breaking into property and painting it might seem a little inconsiderate, but in reality the 30 square centimeters of your brain are trespassed upon every day by teams of marketing experts. Graffiti is a perfectly proportionate response to being sold unattainable goals by a society obsessed with status and infamy. Graffiti is the sight of an unregulated free market getting the kind of art it deserves."

Overview of Street and Graffiti Art

Street Art is supposed to be the ultimate in democratized art; seen by everyone, owned by no-one. But this hasn't stopped a Banksy becoming the movement's ultimate collectible; with celebrities including Justin Bieber, Serena Williams and Angelina Jolie, having acquired the elusive artist’s work.

Artworks and Artists of Street and Graffiti Art

Untitled (Tag on Pole)

This work serves as an early example of tagging, the type of graffiti writing in which the writer scrawls his/her pseudonym (also known as their "tag") using spray paint or marker, as quickly as possible in as many locations as possible, with the goal of "getting up", or gaining credibility and fame for proliferating one's name around the city. An artist's tag is a pseudonym, which protects both the individual's identity and anonymity, while simultaneously providing the writer an opportunity to develop a new identity or persona (much like a digital avatar). In fact, TAKI 183 is often credited as being the first tagger (although some argue that CORNBREAD of Philadelphia was the first). As journalist Norman Mailer paraphrased the words of graffiti artist CAY 161, "the name is the faith of graffiti." More than anything else, graffiti writers convey their identity and their existence by painting their tag in public spaces. Although considered more as vandalism than art, tagging proliferated the idea that one could become known by demonstrating their presence in public spaces, thus providing the raw foundation for artists to evolve out from within.

Permanent Marker - New York City

Untitled (New York Subway Graffiti)

The text in this "piece" (the common term for a work of graffiti art) reads "TRAP DEZ DAZE" (the tags/pseudonyms of the artists), although the style and placement of the letters may make it difficult to discern for viewers not familiar with this style of lettering. The text uses several bright colors, and employs outlining and shading to give the impression of three-dimensionality. This piece, like much New York graffiti of the 1980s, was completed on the side of a subway train. This choice of location would have garnered greater prestige for the artists, as writing on subway cars put them at very high risk of apprehension by the authorities, and thus considered more daring. Writing on subway cars was also a sure way to rapidly increase one's fame, as the artwork would then travel around the city's subway system, being seen by a far greater number of people than would a stationary piece on a wall.

This piece is a typical example of "wildstyle" graffiti, which includes complex, interlocking or overlapping letters, and sometimes cartoon-like characters and other images, all painted in bright colors. Photojournalist Martha Cooper noted in 1982 that "inaccessibility reinforces that sense of having a secret society inaccessible to outsiders [...] a writer will therefore often make a piece deliberately hard to read." As well, graffiti writers frequently attempt to create a sense of depth and three-dimensionality in wildstyle works. These types of pieces garner higher levels of respect for writers as opposed to "throwups" (simpler pieces using maximum two or three colors to create two-dimensional bubble text) or "tags", because wildstyle work involves more artistic prowess and takes longer to complete, thus putting the writer at a higher risk for run-ins with police.

Spray paint - New York City

Tango

This work, created by spray-painting onto a wall over a pre-cut stencil, depicts a couple in the midst of dancing. As we can see, the use of the stencil allowed the artist to create a striking, sharp image with clean, crisp lines, using only black spray paint over a white surface.

In 1971, Blek le Rat took a trip to the United States, where he was amazed by the graffiti he saw all over the city centers. When he returned to Paris, he began to try his own hand at this form of expression. Seeing Fascist stencils in Italy during his youth, as well as political paintings in French Algeria, left a lasting impression on him, and in 1981 he decided to start making his own stencil works around Paris, beginning with small rats. Like Bristol's Banksy, Blek le Rat sees the rat as an ideal symbol for the graffiti artist, as both operate under cover of darkness to evade capture and eradication. Blek le Rat explains, "I began to spray some small rats in the streets of Paris because rats are the only wild animals living in cities, and only rats will survive when the human race disappears and dies out." He then moved on to larger stencil projects, becoming the first known artist to work with stencils to create pictures rather than just text. He explains the benefits of working with stencils, saying, "There are no accidents with stencils. Images created this way are clean and beautiful. You prepare it in your studio and then you can reproduce it indefinitely. I'm not good enough to paint freehand. Stencil is a technique well suited to the streets because it's fast. You don't have to deal with the worry of the police catching you."

Spray paint - Frasso Telesino, Italy

Tuttomondo

This mural in the historic city of Pisa in Tuscany is filled with graffiti artist Keith Haring's signature motifs including his generic "radiant" figures and many other illuminated forms. It is universally recognized as the artist's unmistakable cartoonish Pop style. The work is a good example of the way some renegade street artists were able to move from their unsanctioned urban canvases into a credible art forum. Haring's notoriety in the public consciousness catapulted him to the type of fame that motivated a city to commission his unique style for their own public building.

Haring first gained attention with his subway art that was created using white chalk on black, unused advertisement backboards in the underground stations that were his preferred painting "laboratory." The radiant baby became his most popular symbol, first used as his identifying tag before taking a life of its own as his preferred character. His bold lines, vivid colors, and active figures carried strong messages of life and unity. He often used lines of energy to emphasize kinetic movement, vitality, and euphoric spirit.

By 1982, Haring had established friendships with fellow emerging street artists Futura 2000, Kenny Scharf, and Jean-Michel Basquiat. He also became close friends with Andy Warhol. His work grew more politically active during the era of AIDS and his popular "Silence Equals Death" imagery became a key branding visual for New York's HIV activist group ACT UP. He created more than 50 public works between 1982 and 1989 in dozens of cities around the world.

In April 1986, Pop Shop was opened in Soho and made Haring's work readily accessible to purchase at reasonable prices. When asked about the commercialism of his work, Haring said: "I could earn more money if I just painted a few things and jacked up the price. My shop is an extension of what I was doing in the subway stations, breaking down the barriers between high and low art."

Mural - Pisa, Italy

Obey Giant

In 1998, American street artist Shepard Fairey, who spawned from the Southern California skateboarding culture, created a graphic sticker campaign inspired by wrestling icon Andre the Giant while attending the Rhode Island School of Design. The stickers, written with the words Obey Giant, popped up all over the urban landscapes where Fairey lived and traveled, becoming the artist's visual, public experiment with phenomenology. Inspired by German philosopher Martin Heidegger's description of phenomenology as "the process of letting things manifest themselves," Fairey was attempting to enable people to see clearly something that is right before their eyes, but obscured; things so taken for granted that they become muted by abstract observation. Thus, the famous wrestler's face became a familiar motif on the streets, its repetition causing notice while remaining meaningless, until it eventually became just another familiar piece of the urban landscape, unquestioned or analyzed.

Fairey became widely known during the 2008 presidential election for his Barack Obama HOPE poster. He is one of the most influential street artists who have crossed into the gallery zone as he is included in collections at The Smithsonian, the Los Angeles Country Museum of Art and the Museum of Modern Art in New York City among others.

Hip Hop Rat

This graffiti piece features a black and white stenciled rat. Banksy often uses the image of the rat as a personalized symbol representing himself, as he, like his graffiti artist predecessor Blek le Rat, felt an affinity with this city-dwelling creature that is active at night in order to evade apprehension and eradication. He says, "If you feel dirty, insignificant or unloved, then rats are a good role model. They exist without permission, they have no respect for the hierarchy of society, and they have sex 50 times a day."

Since the 1990s, Banksy has rapidly risen to international fame, arguably becoming one of, if not the most well-known contemporary street artists, despite maintaining anonymity by keeping his true identity a secret. His works have sold at auction for hundreds of thousands, even millions of dollars. Much of his work (especially in his earlier days) used stencils, allowing him to execute pieces in a matter of seconds and remain undetected by authorities. Since the early 2000s, he has also executed other types of unsanctioned interventions, including sculptures and performative actions. Most of his work aims to offer political and social criticism. Soldiers and police officers, as well as popular cultural icons (like Ronald McDonald and Mickey Mouse) recur in many of his pieces. He marked the end of the 2009 United Nations Climate Change Conference by painting four murals on global warming. One included the phrase, "I don't believe in global warming" submerged in water. In 2005 he traveled to the Israel-Palestine West Bank barrier wall and executed nine murals on the wall (including a dove with a bulletproof vest and a heart-shaped target over its chest, a child beneath a ladder stretching to the top of the wall, and the silhouette of a young girl being lifted upwards by a bunch of balloons).

Banksy has also held various notable exhibitions, such as his 2006 Barely Legal show in a Los Angeles warehouse, which featured a live Indian elephant painted with the same red and gold floral pattern as the wallpaper that was pasted up in the section of the warehouse where the elephant was displayed. This created controversy, as animal rights activists protested the elephant's involvement. However, the show was immensely popular, with several A-list Hollywood celebrities in attendance. Another one of Banksy's exhibitions, Banksy vs. Bristol Museum (2009) featured Banksy's own take on famous historical paintings, as well as animatronics, sculptures, and installations.

Spray paint

Untitled (Guantanamo Prisoner at Disneyland)

In September of 2006, Banksy snuck a life-size inflatable doll dressed as a Guantanamo Bay prisoner into the Disneyland theme park in California, and installed it within the confines of the Big Thunder Mountain Railroad ride. The work remained in place for over an hour before park officials noticed it, shut down the ride, and removed the doll. A spokeswoman for Banksy said the work was intended to highlight the situation in which terror suspects find themselves in at the controversial detention center in Cuba. The artist hoped that by confronting carefree park-goers with what appeared to be an actual Guantanamo Bay prisoner in "the happiest place on earth," he might shock them into thinking more seriously about the implications of the war on terror. This work serves as a prime example of how sculptural works by street artists are particularly useful in orchestrating jarring experiences that reflect the political or social climate.

Banksy has carried out a number of other such performative illegal interventions. In 2004, he produced 100,000 fake British £10 notes, replacing the picture of the Queen's head with that of Diana, Princess of Wales and changing the text "Bank of England" to "Banksy of England." He tossed these into a crowd at the Notting Hill Carnival that same year, which some people then attempted to spend in local shops. In March 2005, he surreptitiously hung various modified artworks of his own (such as a Warhol-esque painting of a discount soup can) in New York City's Museum of Modern Art, Metropolitan Museum of Art, American Museum of Natural History in Manhattan, and Brooklyn Museum. In August/September of 2006, he placed approximately 500 fake copies of Paris Hilton's debut CD, Paris, in 48 record stores around the UK, modified with his own cover art (photoshopped to show Hilton topless). Other pictures in the album insert featured Paris with her chihuahua Tinkerbell's head replacing her own, and one of her stepping out of a luxury car, edited to include a group of homeless people, with the caption "90% of success is just showing up." Music tracks were given titles such as "Why Am I Famous?" "What Have I Done?" and "What Am I For?" The public purchased several copies of the CD before stores were able to remove them. The purchased copies went on to be sold for much more on online auction websites.

Inflatable doll, orange jumpsuit, black hood, and handcuffs - Disneyland, California

Art Less Pollution

This work, which took seventeen nights to complete, serves as an example of "reverse" graffiti, in that the artist did not actually apply any material to the surface of the wall where he was working, but rather, created images of over 3,500 human skulls in a space measuring almost 1000 feet long, by merely wiping away the heavy layer of soot that had accumulated on the wall of this transportation tunnel from vehicle exhaust pipes. Here, the repeated skull image, combined with the method of image creation, conveys the idea that the pollution of urban centers is a deadly problem affecting countless people. Orion says that, "I wanted to bring a catacomb from the near future to the present, to show people that the tragedy of pollution is happening right now."

Reverse graffiti poses a unique problem for law enforcement officers, who are generally conditioned to understand Street Art as a form of vandalism. However, in the case of reverse graffiti works such as this, the artist has done little more than clean a portion of a public surface. Orion explains, "There is no crime in cleaning. The crime here is against the environment, it is a crime against life." Authorities in Sao Paulo ultimately decided that there was nothing they could charge Orion with, and the episode even prompted city officials to order the monthly cleaning of every transportation tunnel in the city.

Scraped-off soot - Max Feffer Tunnel, Sao Paulo, Brazil

Liquidated Chanel Logo

French street artist Aguirre Schwarz, better known by his tag "ZEVS" (pronounced as "Zeus") creates what he calls "Visual Violations," taking spray paint to public advertisements in his Liquidated Logos series. This series involves the application of water-based paint, which drips down heavily from well-known corporate logos (such as the luxury design house Chanel and the fast food restaurant McDonald's). He first created works illegally in public spaces, "liquidating" logos on billboards, storefronts, and city walls, and later adapted them for his gallery shows. Cultural critic and curator Carlo McCormick has referred to ZEVS as the "most subversive" of all contemporary French street artists. In fact, Zevs was arrested in Hong Kong in 2009 after spraying this liquidated Chanel logo on the side of a Giorgio Armani shop.

Indeed, throughout the history of Street Art, artists have commonly targeted public advertisements and corporate space as a rebellion against the consumerism and commercialization that pervades contemporary society. These artists have adopted a confrontational attitude toward marketing, asking: If advertisers are permitted to visually pollute purportedly "public" places, why can't citizens be a part of that dialogue? As cultural critic and curator Carlo McCormick writes, "One of the most salient features of graffiti is its approximation of branding. At its most basic level, the tag mimics the ideographic compression, repetition, and saturation that we would expect of corporate logos and marketing campaigns." Banksy argues that, "To some people breaking into property and painting it might seem a little inconsiderate, but in reality the 30 square centimetres of your brain are trespassed upon every day by teams of marketing experts. Graffiti is a perfectly proportionate response to being sold unattainable goals by a society obsessed with status and infamy. Graffiti is the sight of an unregulated free market getting the kind of art it deserves."

In recent years, ZEVS has been recreating his Liquidated Logos on canvas and exhibiting them in galleries, such as at his 2011 solo show Liquidated Version at the De Buck Gallery in Chelsea, New York City. While the formal qualities and compositions of his paintings remain identical to one another, their subversive power is diminished when relocated in the rarified environment of a gallery or museum. The Liquidated Logos, when seen in the street, explicitly and directly confront corporate capitalism. Bold graffiti imagery in public spaces surprises viewers through visual appropriation of recognizable motifs, and these familiar yet perverted slogans register as protest and vandalism. Meanwhile, the same imagery in a gallery space lacks the agitation, hostility, and contradiction, which according to art historian Claire Bishop, "can be crucial to any work's artistic impact."

Paint - Hong Kong

Bethlehem Boys

This wheat paste poster work, installed on the wall and window of a shop front, depicts three young boys wearing baggy pants, sweaters, and sneakers. The two older boys look out at the viewer, one of them with his mouth partly opened, as if addressing passers-by and implicating them in the work.

SWOON (née Caledonia Curry) is a female street artist who was born in New London, Connecticut, raised in Daytona Beach, Florida, and now resides in New York City. She began creating Street Art in 1999, spending several days in her studio preparing wheat paste posters made of recycled newspaper, and then transporting the finished works to urban public spaces where she pasted them onto walls. She, like many other street artists, favors this method as it allows her to execute detailed works while spending minimal time at the intended location. She has explained that Street Art was important to her as it allowed her to have an impact on the urban landscape, rather than disappearing into obscurity by creating commercial art that would remain hidden inside a gallery or private collection.

SWOON's wheat paste works frequently depict people, including her friends, family members, and other individuals she has seen in the locations where she executes her works. Culture critic and curator Carlo McCormick writes of SWOON's figures that, "when you pass a figure by an artist like SWOON, the effect has the familiarity of an old neighbor you have not seen for a long while." He explains that a great deal of public art and Street Art is based on the desire to remember and commemorate common people and events, as evidenced by the phenomenon of memorial graffiti carried out in Latino communities in the United States and the UK, and in the 2003 Ghost Bike movement in the United States, where white bicycles were placed at the sites of road accidents where cyclists were killed. In her own way, SWOON leaves traces of people she knows, allowing their spirits to live on in the community even though they may have gone, or grown older and changed.

Recycled newspaper, paint, and wheat paste - St. Louis, Missouri

Beginnings of Street and Graffiti Art

Precursors to Contemporary Graffiti and Street Art

Graffiti, defined simply as writing, drawing, or painting on walls or surfaces of a structure, dates back to prehistoric and ancient times, as evidenced by the Lascaux cave paintings in France and other historic findings across the world. Scholars believe that the images of hunting scenes found at these sites were either meant to commemorate past hunting victories, or were used as part of rituals intended to increase hunters' success.

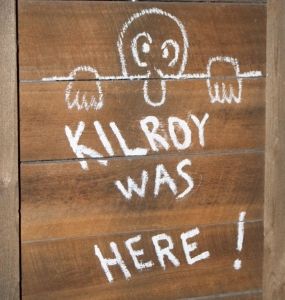

During World War II, it became popular for soldiers to write the phrase "Kilroy was here," along with a simple sketch of a bald figure with a large nose peeking over a ledge, on surfaces along their route. The motivation behind this simple early graffiti was to create a motif of connection for these soldiers during their difficult times, cementing their unique brotherhood amongst foreign land and to make themselves "seen." This was closely aligned with the motivation behind contemporary graffiti, with the writers aiming to assert their existence and to repeat their mark in as many places as possible.

Beginnings of Contemporary Graffiti in the United States

Contemporary (or "hip-hop") graffiti dates to the late 1960s, generally said to have arisen from the Black and Latino neighborhoods of New York City alongside hip-hop music and street subcultures, and catalyzed by the invention of the aerosol spray can. Early graffiti artists were commonly called "writers" or "taggers" (individuals who write simple "tags," or their stylized signatures, with the goal of tagging as many locations as possible.) Indeed, the fundamental underlying principle of graffiti practice was the intention to "get up," to have one's work seen by as many people as possible, in as many places as possible.

The exact geographical location of the first "tagger" is difficult to pinpoint. Some sources identify New York (specifically taggers Julio 204 and Taki 183 of the Washington Heights area), and others identify Philadelphia (with tagger Corn Bread) as the point of origin. Yet, it goes more or less undisputed that New York "is where graffiti culture blossomed, matured, and most clearly distinguished itself from all prior forms of graffiti," as Eric Felisbret, former graffiti artist and lecturer, explains.

Soon after graffiti began appearing on city surfaces, subway cars and trains became major targets for New York City's early graffiti writers and taggers, as these vehicles traveled great distances, allowing the writer's name to be seen by a wider audience. The subway rapidly became the most popular place to write, with many graffiti artists looking down upon those who wrote on walls. Sociologist Richard Lachmann notes how the added element of movement made graffiti a uniquely dynamic art form. He writes, "Much of the best graffiti was meant to be appreciated in motion, as it passed through dark and dingy stations or on elevated tracks. Photos and graffiti canvases cannot convey the energy and aura of giant artwork in motion."

Graffiti on subway cars began as crude, simple tags, but as tagging became increasingly popular, writers had to find new ways to make their names stand out. Over the next few years, new calligraphic styles were developed and tags turned into large, colorful, elaborate pieces, aided by the realization that different spray can nozzles (also referred to as "caps") from other household aerosol products (like oven cleaner) could be used on spray paint cans to create varying effects and line widths. It did not take long for the crude tags to grow in size, and to develop into artistic, colorful pieces that took up the length of entire subway cars.

New York City's Graffiti “Problem”

By the 1980s, the city of New York viewed graffiti's inherent vandalism as a major concern, and a massive amount of resources were poured into the graffiti "problem." As Art Historian Martha Cooper writes, "For [New York City mayor Ed] Koch, graffiti was evidence of a lack of authoritarian order; as such, the presence of graffiti had a psychological effect that made all citizens its victim through a disruption of the visual order, thus promoting a feeling of confusion and fear among people." The New York Police cracked down on writers, often following suspect youth as they left school, searching them for graffiti-related paraphernalia, staking out their houses, or gathering information from informants. The Metropolitan Transit Authority (MTA) received a significant increase in their budget in 1982, allowing them to erect more sophisticated fences and to better maintain the train yards and lay-ups that were popular targets for writers (due to the possibility for hitting several cars at once). However, writers saw these measures as a mere challenge, and worked even harder to hit their targets, while also becoming increasingly territorial and aggressive toward other writers and "crews" (groups of writers).

In 1984, the MTA launched its Clean Car Program, which involved a five-year plan to completely eliminate graffiti on subway cars, operating on the principle that a graffiti-covered subway car could not be put into service until all the graffiti on it had been cleaned off. This program was implemented one subway line at a time, gradually pushing writers outward, and by 1986 many of the city's lines were completely clear of graffiti. Lieutenant Steve Mona recalls one day when the ACC crew hit 130 cars in a yard at Coney Island, assuming that the MTA wouldn't shut down service and that the graffitied trains would run. Yet the MTA opted to not provide service, greatly inconveniencing citizens who had to wait over an hour for a train that morning. That was the day that the MTA's dedication to the eradication of graffiti became apparent.

However graffiti was anything but eradicated. In the past few decades, this practice has spread around the world, often maintaining elements of the American wildstyle, like interlocking letterforms and bold colors, yet also adopting local flare, such as manga-inspired Street Art in Japan.

From Graffiti to Street Art: Greater Variation in Styles, Techniques, and Materials

It is important to note that contemporary graffiti has developed completely apart from traditional, institutionalized art forms. Art critic and curator Johannes Stahl writes that, "We have long since got accustomed to understanding art history as a succession of epochs [...] But at the same time there has always existed something outside of official art history, a unruly and recalcitrant art, which takes place not in the sheltered environs of churches, collections or galleries, but out on the street." Graffiti artists today draw inspiration from Art History at times, but it cannot be said that graffiti grew directly out of any such canon or typology. Modern graffiti did not begin as an art form at all, but rather, as a form of text-based urban communication that developed its own networks. As Lachmann notes, rather than submitting to the criteria of valuation upheld by the institutionalized art world, early graffiti writers developed an entirely new and separate art world, based on their own "qualitative conception of style" and the particular "aesthetic standards" developed within the community for judging writers' content and technique.

During the late 1970s and early 1980s, many graffiti writers began to shift away from text-based works to include imagery. Key artists involved in this shift included Jean-Michel Basquiat (who wrote graffiti using the tag SAMO) and Keith Haring, whose simple illuminated figures gave testament to the AIDS epidemic, both of whom were active in New York City. Around the same time, many artists also began experimenting with different techniques and materials, the most popular being stencils and wheat paste posters.

Concepts and Styles

Since the turn of the millennium, this proliferation has continued, with artists using all sorts of materials to complete illegal works in pubic spaces. The myriad approaches have come to be housed under the label of "Street Art" (sometimes also referred to as "Urban Art"), which has expanded its purview beyond graffiti to include these other techniques and styles.

Graffiti

The term "graffiti" comes from the Greek "graphein," meaning "to scratch, draw, or write," and thus a broad definition of the term includes all forms of inscriptions on walls. More specifically, however, the modern, or "hip-hop" graffiti, that has pervaded city spaces since the 1960s and 1970s involves the use of spray paint or paint markers. It is associated with a particular aesthetic, most often utilizing bold color choices, involving highly stylized and abstract lettering known as "wildstyle," and/or including cartoon-like characters.

Photographer and author Nicolas Ganz notes that graffiti and Street Art practices are characterized by differing "sociological elements," writing that graffiti writers continue to be "governed by the desire to spread one's tag and achieve fame" through both quality and quantity of pieces created, while street artists are governed by "fewer rules and [embrace] a much broader range of styles and techniques." Anthropologist and archaeologist Troy Lovata and art historian Elizabeth Olson write that "the rapid proliferation of this aggressive style of writing appearing on the walls of urban centres all over the world has become an international signifier of rebellion," and cultural theorist Jean Baudrillard has called it the "symbolic destruction of social relations."

Stencils

Stencils (also known as stencil graffiti) are usually prepared beforehand out of paper or cardboard and then brought to the site of the work's intended installation, attached to the wall with tape, and then spray painted over, resulting in the image or text being left behind once the stencil is removed. Many street artists favor the use of stencils as opposed to freehand graffiti because they allow for an image or text to be installed very easily in a matter of seconds, minimizing the chance of run-ins with the authorities. Stencils are also preferable as they are infinitely re-useable and repeatable. Sometimes artists use multiple layers of stencils on the same image to add colors, details, and the illusion of depth. Brighton-based artist Hutch explains that he prefers to stencil because "it can produce a very clean and graphic style, which is what I like when creating realistic human figures. Also, the effect on the viewer is instant, you don't need to wait for it to sink in."

One of the earliest known street artists to use stencils was John Fekner, who started using the technique in 1968 to stencil purely textual messages onto walls. Other well-known stencil artists include French artists Ernest Pignon-Ernest and Blek le Rat, British artists Nick Walker and Banksy, and American artists Shepard Fairey and Above.

Wheat Paste Posters

Wheat paste (also known as flour paste) is a gel or liquid adhesive made from combining wheat flour or starch with water. Many street artists use wheat paste to adhere paper posters to walls. Much like stencils, wheat paste posters are preferable for street artists as it allows them to do most of the preparation at home or in the studio, with only a few moments needed at the site of installation, pasting the poster to the desired surface. This is crucial for artists installing works in unsanctioned locations, as it lowers the risk of apprehension and arrest. Some street artists who use the wheat paste method include Italian duo Sten and Lex, French artists JR and Ludo, and American artist Swoon.

Sculptural Street Art Interventions

Some street artists create three-dimensional sculptural interventions, which can be installed surreptitiously in public spaces, usually under the cover of darkness. This type of work differs from Public Art in that it is rebellious in nature and completed illegally, while Public Art is officially sanctioned/commissioned (and thus more palatable to a general audience). Unsanctioned Street Art interventions usually aim to shock viewers by presenting a visually realistic, yet simultaneously unbelievable situation. For instance, in his Third Man Series (2006), artist Dan Witz installs gloves on sewer grates to give the impression that a person is inside the sewer attempting to escape. Works like these often cause passers-by to do a "double-take."

Reverse Graffiti

Reverse graffiti (also known as clean tagging, dust tagging, grime writing, clean graffiti, green graffiti, or clean advertising) is a method by which artists create images on walls or other surfaces by removing dirt from a surface. According to British reverse graffiti artist Moose, "Once you do this, you make people confront whether or not they like people cleaning walls or if they really have a problem with personal expression." This sort of work calls attention to environmental concerns in urban spaces, such as pollution.

Other Media

There are street artists who experiment with other media, such as Invader (Paris), who adheres ceramic tiles to city surfaces, recreating images from the popular Space Invaders video game of 1978. Invader says that tile is "a perfect material because it is permanent. Even after years of being outside the colors don't fade."

Many other artists use simple stickers, which they post on surfaces around the city. Often, these stickers are printed with the artist's tag or a simple graphic. Others invite participation from the audience, like Ji Lee who pastes empty comic speech-bubbles onto advertisements, allowing passers-by to write in their own captions.

Others still use natural materials to beautify urban spaces. For instance, in 2005, Shannon Spanhake planted flowers in various potholes of the streets in Tijuana, Mexico. She says of the project, "Adorning the streets of Tijuana are potholes, open wounds that mark the failure of man's Promethean Project to tame nature, and somehow surviving in the margins are abandoned buildings, entropic monuments celebrating a hyperrealistic vision of a modernist utopia linked to capitalist expansion gone awry."

There are also artists who create Street Art interventions through the use of clay, chalk, charcoal, knitting, and projected photo/video. The possibilities for Street Art media are endless.

Later Developments - After Street and Graffiti Art

Mainstream Acceptance

Street Art continues to be a popular category of art all over the world, with many of its practitioners rising to fame and mainstream success (such as Bristol's Banksy, Paris' ZEVS, and L.A.'s Shepard Fairey). Street artists who experience commercial success are often criticized by their peers for "selling out" and becoming part of the system that they had formerly rebelled against by creating illegal public works. Communications professor Tracey Bowen sees the act of creating graffiti as both a "celebration of existence" and "a declaration of resistance." Similarly, Slovenian Feminist author Tea Hvala views graffiti as "the most accessible medium of resistance" for oppressed people to use against dominant culture due to its tactical (non-institutional, decentralized) qualities. For both Bowen and Hvala these unique positive attributes of graffiti are heavily reliant on its location in urban public spaces. Art critic and curator Johannes Stahl argues that the public context is crucial for Street Art to be political, because "it happens in places that are accessible to all [and] it employs a means of expression that is not controlled by the government." Street artist BOOKSIIII holds an opinion not uncommon of many of today's street artists, that it is not inherently wrong for young artists to try to make money from galleries and corporations for their works, "as long as they do their job honestly, sell work, and represent careers," yet at the same time he notes that "graffiti does not stay the same when transferred to the gallery from the street. A tag on canvas will never hold the same power as the exact same tag on the street."

This movement from the street to the gallery also indicates a growing acceptance of graffiti and Street Art within the mainstream art world and art history. Some apply the label "post-graffiti" to the work of street artists that also participate in the mainstream art world, although this is somewhat of a misnomer, as many such artists continue to execute illegal public interventions at the same time as they participate in sanctioned exhibitions in galleries and museums. This phenomenon also presents difficulties for art historians, as the sheer number of street artists, as well as their tendency to maintain anonymity, makes it hard to engage with individual artists in any sort of profound way. Moreover, it is difficult to insert Street Art into the art historical canon, as it did not develop from any progression of artistic movements, but rather began independently, with early graffiti and street artists developing their own unique techniques and aesthetic styles. Today, street artists both inspire and are inspired by many other artistic movements and styles, with many artists' works bearing elements of wide-ranging movements, from Pop Art to Renaissance Art.

Legality

Street Art's status as vandalism often eclipses its status as art. More recently, as mentioned above, many artists are finding more opportunities to create artworks in sanctioned situations, by showing in galleries and museums, or by partnering with organizations that offer outdoor public spaces in which street artists are permitted to execute works. However, many others continue to focus on unsanctioned illegal works. Part of the allure of working illegally has to do with the adrenaline rush that artists get from successfully executing a piece without being apprehended by the authorities. Moreover, carrying out illegal/unsanctioned attacks on privately owned surfaces (such as a billboard being rented out by an advertising agency, or a politically-charged surface such as border walls), serves as a direct confrontation with the owner of that space (be it a marketing firm, or a political entity).

Technology and the Internet

With the advent of the Internet and the development of various graphic software and technologies, street artists now have a multitude of tools at their fingertips to assist in the creation and dissemination of their works. Specialized computer programs allow artists (like San Francisco-born MOMO) to better plan for their graffiti pieces and prepare their stencils and wheat paste posters, while digital photography used in conjunction with the Internet and social media allows Street Art works to be documented, shared, and thus immortalized where previously, most pieces tended to disappear when they were removed by city authorities or painted over by other artists.

Useful Resources on Street and Graffiti Art

- Banksy: The Man Behind the WallBy Will Ellsworth-Jones

- Banksy: Art Breaks the RulesBy Hettie Bingham

- Banksy in New YorkBy Ray Mock

- Banksy. Myths & Legends: A Collection of the Unbelievable and the IncredibleBy Marc Leverton

- Covert to Overt: The Under/Overground Art of Shepard FaireyBy Shepard Fairey

- OBEY: Supply and DemandBy Shepard Fairey

- Street Art: The Graffiti RevolutionOur PickBy Cedar Lewisohn

- Street Art: Famous Artists Talk About Their VisionBy Alessandra Mattanza

- Street Art: InternationalBy Lou Chamberlin

- Urban Art LegendsBy KET

- Street Art Today: The 50 Most Influential Street Artists TodayBy Björn Van Poucke and Elise Luong

- Street Art WorldBy Alison Young

- Street Art from Around the WorldBy Garry Hunter

- Global Street Art: The Street Artists and Trends Taking Over the WorldBy Lee Bofkin

- It's a Stick-Up: 20 Real Wheat Paste-Ups from the World's Greatest Street ArtistsBy Ollystudio Limited

- Understanding Graffiti: Multidisciplinary Studies from Prehistory to the PresentOur PickBy Troy Lovata and Elizabeth Olton

- Graffiti World (Updated Edition): Street Art from Five ContinentsOur PickBy Nicolas Ganz

- Street Fonts: Graffiti Alphabets from Around the WorldBy Claudia Walde

- The World Atlas of Street Art and GraffitiOur PickBy Rafael Schacter

- Subway ArtOur PickBy Henry Chalfant and Martha Cooper

- Graffiti Women: Street Art from Five ContinentsOur PickBy Nicolas Ganz

- Graffiti L.A.: Street Styles and ArtBy Steve Grody

- Freight Train GraffitiBy Roger Gastman, Darin Rowland, and Ian Sattler

- Graffiti Kings: New York City Mass Transit Art of the 1970sBy Jack Stewart

- Graffiti New YorkOur PickBy Eric Felisbret

- The Faith of GraffitiOur PickBy Norman Mailer and Jon Naar

Ask The Art Story AI

Ask The Art Story AI